Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow

"Remote Learning During the Global School Lockdown: Multi-Country Lessons” and “Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow"

WHY A TWIN REPORT ON THE IMPACT OF COVID IN EDUCATION?

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted education in over 150 countries and affected 1.6 billion students. In response, many countries implemented some form of remote learning. The education response during the early phase of COVID-19 focused on implementing remote learning modalities as an emergency response. These were intended to reach all students but were not always successful. As the pandemic has evolved, so too have education responses. Schools are now partially or fully open in many jurisdictions.

A complete understanding of the short-, medium- and long-term implications of this crisis is still forming. The twin reports analyze how this crisis has amplified inequalities and also document a unique opportunity to reimagine the traditional model of school-based learning.

The reports were developed at different times during the pandemic and are complementary:

The first one follows a qualitative research approach to document the opinions of education experts regarding the effectiveness of remote and remedial learning programs implemented across 17 countries. DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

WHAT ARE THE LESSONS LEARNED OF THE TWIN REPORTS?

- Availability of technology is a necessary but not sufficient condition for effective remote learning: EdTech has been key to keep learning despite the school lockdown, opening new opportunities for delivering education at a scale. However, the impact of technology on education remains a challenge.

- Teachers are more critical than ever: Regardless of the learning modality and available technology, teachers play a critical role. Regular and effective pre-service and on-going teacher professional development is key. Support to develop digital and pedagogical tools to teach effectively both in remote and in-person settings.

- Education is an intense human interaction endeavor: For remote learning to be successful it needs to allow for meaningful two-way interaction between students and their teachers; such interactions can be enabled by using the most appropriate technology for the local context.

- Parents as key partners of teachers: Parent’s involvement has played an equalizing role mitigating some of the limitations of remote learning. As countries transition to a more consistently blended learning model, it is necessary to prioritize strategies that provide guidance to parents and equip them with the tools required to help them support students.

- Leverage on a dynamic ecosystem of collaboration: Ministries of Education need to work in close coordination with other entities working in education (multi-lateral, public, private, academic) to effectively orchestrate different players and to secure the quality of the overall learning experience.

- FULL REPORT

- Interactive document

- Understanding the Effectiveness of Remote and Remedial Learning Programs: Two New Reports

- Understanding the Perceived Effectiveness of Remote Learning Solutions: Lessons from 18 Countries

- Five lessons from remote learning during COVID-19

- Launch of the Twin Reports on Remote Learning during COVID-19: Lessons for today, principles for tomorrow

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2023

The impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on students’ attainment, analysed by IRT modelling method

- Rita Takács ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0314-4179 1 ,

- Szabolcs Takács ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9128-9019 2 , 3 ,

- Judit T. Kárász ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6198-482X 4 , 5 ,

- Attila Oláh 6 , 7 &

- Zoltán Horváth 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 127 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3487 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Universities around the world were closed for several months to slow down the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this crisis, a tremendous amount of effort was made to use online education to support the teaching and learning process. The COVID-19 pandemic gave us a profound insight into how online education can radically affect students and how students adapt to new challenges. The question is how switching to online education affected dropout? This study shows the results of a research project clarifying the impact of the transition to online courses on dropouts. The data analysed are from a large public university in Europe where online education was introduced in March 2020. This study compares the academic progress of students newly enroled in 2018 and 2019 using IRT modelling. The results show that (1) this period did not contribute significantly to the increase in dropout, and we managed to retain our students.(2) Subjects became more achievable during online education, and students with less ability were also able to pass their exams. (3) Students who participated in online education reported lower average grade points than those who participated in on-campus education. Consequently, on-campus students could win better scholarships because of better grades than students who participated in online education. Analysing students’ results could help (1) resolve management issues regarding scholarship problems and (2) administrators develop programmes to increase retention in online education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Applying the Rasch model to analyze the effectiveness of education reform in order to decrease computer science students’ dropout

Online vs in-person learning in higher education: effects on student achievement and recommendations for leadership

Medium- and long-term outcomes of early childhood education: experiences from Turkish large-scale assessments

Introduction.

During the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries closed their university buildings and switched to online education. Some opinions suggest that online education had a negative effect on dropouts because of several factors, e.g., lack of social connections, poor contact with teachers. In bachelor’s programmes—like university courses in computer science—where dropout rates were high prior to the pandemic, many questions were raised about the impact of the transition to online education.

This study focuses on the effects of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ dropouts and performance in Hungary. Although the manuscript addresses academic dropout, other issues such as inequality or accessibility were also covered in the research.

Theoretical background

Educational theory about student dropout in higher education.

Tinto ( 1975 ) was the first researcher who analysed the dropout phenomenon and invented the interactional theory of student persistence in higher education. He ( 2012 ) highlighted the interactions between the student and the institution regarding how well they fit in academically and socially. Interactional theories suggest that students’ personal characteristics, traits, experience, and commitment can have an effect on students’ persistence (Pascarella and Terenzini, 1983 ; Terenzini and Reason, 2005 ; Reason, 2009 ). Braxton and Hirschy ( 2004 ) also emphasized the need for community on campus as a help of social integration to develop relationships between peers because interactions with other students and faculty members crucially determine whether students persist and continue their studies or leave.

The student dropout rate has been a crucial issue in higher education in the last two decades. Attrition has serious consequences on the individual (e.g., Nagrecha et al., 2017 ) at both economic (Di Pietro, 2006 ; Belloc et al., 2011 ) and educational (Cabrera et al., 2006 ) levels. As a worldwide phenomenon, it draws the attention of policy-makers, stake-holders and academics to the necessity of seeking solutions. The dropout crisis requires complex intervention programmes for encouraging students in order to complete their studies. Addressing such a dropout crisis requires an actionable interdisciplinary movement based on partnerships among stake-holders and academics.

According to Vision 2030 studies published by the European Union, education is vital for economic development because it has a direct influence on entrepreneurship and productivity growth; at the same time, it increases employment opportunities and women empowerment. Education helps to reduce unemployment and enhance students’ abilities and skills that will be needed in the labour market. Due to students’ high attrition, the economy also suffers because experts with a degree usually contribute more to the GDP than people without (Whittle and Rampton, 2020 ).

A comparative analysis of past studies has been conducted in order to identify various causes of students’ dropout. Students’ performance after the first academic year is a topic of significant interest: the lack of students' engagement in academic life and their unpreparedness are mainly responsible for dropout after the first highly crucial period. However, further studies are necessary to better understand this phenomenon.

The characteristics of online education and its effect on dropout

Online education had already existed before the COVID-19 pandemic and had had a vast literature because online courses had been playing an important role in higher education. Online education has its own benefits, e.g., it enables students to work from the comfort of their homes with more convenient, accessible materials. In recent years, numerous investigations have been performed on how to increase the motivation of students by making them feel engaged during the learning processes (Molins-Ruano et al., 2014 ; Jovanovic et al., 2019 ). The other benefit is “humanizing”, which is an academic strategy that looks for solutions to improve equity gaps by recognizing the fact that learning situations are not the same for everyone. The aim of humanizing education is to remove the affective and cognitive barriers which appear during online learning and to provide a technique in higher education towards a more equitable future in which the success of all students is supported (Pacansky-Brock and Vincent-Layton, 2020 ). Humanizing online STEM courses has specific significance because creating such academic pathways can especially help the graduation of vulnerable, for example, non-traditional students. The definition of a non-traditional student belongs to Bean and Metzner ( 1985 ), who distinguished students by different characteristics. Non-traditional students are not on-campus students (but they can participate in online education), who are usually aged 24 years or older, and dominantly have a job and/or a family. Non-traditional students have less interaction with other participants in education, and they are much more influenced by other factors, e.g., family or other external responsibilities. Financial factors, family attitudes and external incentives can also influence dropout. The dropout model for non-traditional university students highlights that underperforming students are likely to leave the institution. Carr ( 2000 ) (in Rovai, 2003 ) noticed that persistence in online courses is regularly 10–20% lower than in on-campus courses. The dropout rate differs from institution to institution: some reports claim that 80% of students graduated, whereas other findings show that less than 50% of students completed their courses. Humanizing recognizes that engagement and accomplishment are the key factors in students’ success. Engagement and achievement are social constructs created through students’ experience. Teachers can help students to socialize and adapt to the academic environment by using humanizing practices like a liquid syllabus. Stommel ( 2013 ) also considers that hybrid pedagogy is a useful tool in order to support students’ learning because it helps teachers to implement new learning activities and facilitate collaboration among students.

Despite the various benefits that online education has, the success of students depends on the student’s capacity to independently and effectively engage in the learning process (Wang et al., 2013 ). Online learners are required to be more autonomous, as the exceptional nature of online settings relies on self-directed learning (Serdyukov and Hill, 2013 ). It is therefore especially critical that online learners, compared to their conventional classroom peers, have the self-generated capacity to control and manage their learning activities.

Online education also needs extra attention because the dropout rate is high in online university programmes. Students in online courses are more likely to drop out (Patterson and McFadden, 2009 ; in Nistor and Neubauer, 2010 ). Numerous studies reported much higher dropout rates than in the case of on-campus courses (Willging and Johnson, 2019 ; Levy, 2007 ; Morris et al., 2005 ; Patterson and McFadden, 2009 ; in Nistor and Neubauer, 2010 ). Many factors that lead to dropout were examined in the past. During online courses, students are less likely to form communities or study groups and the lack of learning support can lead to isolation. Consequently, demotivated students who were dedicated to their chosen major, in the beginning, may decide to drop out. Fortunately, there are different ways to support students who study in an online setting depending on their various psychological attributes. These psychological attributes that are connected to dropout have already been examined. One of the most noticeable hypothetical models of university persistence in online education was proposed by Rovai ( 2003 ). He claims that dropout depends on students’ characteristics e.g., learning style, socioeconomic status, studying skills, etc. Besides these factors, the method of education also has an impact on students’ decisions on whether they complete the course or drop out.

It is vital to distinguish the online education that was introduced as a consequence of the COVID-19 lockdown, when universities were forced to move their education to fully online platforms because online education had already existed in some educational institutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on education: Inequalities in home learning and colleges’ provision of distance teaching during school closure of the COVID-19 lockdown

The lives of millions of college students were affected not only by the health and economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic but also by the closure of educational institutions. Home and academic environments were interlaced, and most institutions were caught unprepared. In this article, we examine the effects of the transition to online learning in areas such as academic attainment.

There are several debates on the effectiveness of moving to online education. Since currently there is little literature about the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to how it affects dropouts at universities, it is worth discussing it in order to have an overview of recent studies on students’ performance. The learning environment changed radically during the first wave of the pandemic in the spring semester of 2020. The transition to home learning and teaching in such a short time without any warning or preparation raised concerns and became the focus of attention for researchers, teachers, policymakers, and all those interested in the educational welfare of students.

A potential learning loss was anticipated, possibly affecting students’ cognitive gains in the long term (Andrew et al., 2020 ; Bayrakdar and Guveli, 2020 ; Brown et al., 2020 ); in fact, an increasing number of studies suggested that the lockdown might have far-reaching academic consequences (Bol, 2020 ). In general, results suggest that students’ motivation was substantially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and that academic and relational changes were the most notable sources of stress on both the students’ side (e.g., Rahiem, 2021 ) and the teachers’ side (e.g., Abilleira et al., 2021 ; Daumiller et al., 2021 ). Engzell et al. ( 2021 ) examined nearly 350,000 students’ academic performance before and after the first wave of the pandemic in the Netherlands. Their results suggest that students made very little development while learning from home. Closures also had a substantial effect on students’ sense of belonging and self-efficacy. Academic knowledge loss could be even more severe in countries with less advanced infrastructure or a longer period of college closures (OECD, 2020 ).

Many researchers started to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ mental health and academic performance. Clark et al. ( 2021 ) claim that university students are increasingly considered a vulnerable population, as they experience extremely high levels of stress. They draw attention to the fact that students might suffer more from learning difficulties. Daniels et al. ( 2021 ) used a single survey to collect retrospective self-report data from Canadian undergraduate students ( n = 98) about their motivation, engagement and perceptions of success and cheating before COVID-19, which shows that students’ achievements, goals, engagement and perception of success all significantly decreased, while their perception of cheating increased (Daniels et al., 2021 ). Other studies claim that during the COVID-19 pandemic, students were more engaged in studying and had higher perceptions of success. Studies also show that teachers’ strategies changed as well because of the lack of interaction between teachers and students, which led to the fact that students experienced more stress and were more likely to have difficulties in following the material presented and it could be one of the reasons for poor academic performance. Mendoza et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the relationships between anxiety and students’ performance during the first wave of the pandemic among college students. Anxiety regarding learning mathematics was measured among mathematics students studying at the Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo (UNACH) during the autumn semester of the academic year 2020. The total sample contained 120 students, who were studying the subject of mathematics at different levels. The results showed that there were statistically significant differences in the understanding of the contents presented by the teachers in a virtual way. During the COVID-19 pandemic the levels of mathematical anxiety increased. Teaching mathematics at university in an online format requires good quality digital connection and time-limited submission of assignments. This study draws attention to the negative result of the pandemic, i.e. the levels of anxiety might be greater during online education and not only in mathematics education but also in other subjects. Thus it could have an effect on students’ academic performance. However, the results are contradictory to what Said ( 2021 ) found, i.e. there was no difference in students’ performance before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In their empirical study, they investigated the effect of the shift from face-to-face to online distance learning at one of the universities in Egypt. They compared the grades of 376 business students who participated in a face-to-face course in spring 2019 and those of 372 students who participated in the same course fully online in spring 2020 during the lockdown. A T -test was conducted to compare the grades of quizzes, coursework, and final exams of the two groups. The results suggested that there was no statistically significant difference. Another interesting result was that in some cases students had a better performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. At a large public university in Spain, Iglesias-Pradas et al. ( 2021 ) analysed the following instruction-related variables: class size, synchronous/asynchronous delivery of classes, and the use of digital supporting technologies on students’ academic performance. The research compared the academic results of the students during the COVID-19 pandemic with those of previous years. Using quantitative data from academic records across all ( n = 43) courses of a bachelor’s degree programme, the study showed an increase in students’ academic performance during the sudden shift to online education. Gonzalez et al. ( 2020 ) had similar results. Their research group analysed the effects of COVID-19 on the autonomous learning performance of students. 458 students participated in their studies. In the control group, students started their studies in 2017 and 2018, while in the experimental group, students started in 2019. The results showed that there was a significant positive effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on students’ performance: students had changed their learning strategies and improved their efficiency by studying more continuously. Yu et al. ( 2021 ) found similar results. They used administrative data from students’ grade tracking systems and found that the causal effects of online education on students’ exam performance were positive in a Chinese middle school. Taking a difference-in-differences approach, they found that receiving online education during the COVID-19 lockdown improved students’ academic results by 0.22 of a standard deviation (Yu et al., 2021 ).

Currently, there is little literature about COVID-19 in relation to how it affects students’ performance at universities, so it is worth discussing this aspect as well.

Teachers’ approach to their grading strategies and shift to online education during the COVID-19 lockdown

There is a vast literature on the limits of the capacities and challenges of online education (Davis et al., 2019 ; Dumford and Miller, 2018 ; Palvia et al., 2018 ). The lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic created new challenges for teachers all over the world and called for innovative teaching techniques (Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020 ; Gamage et al., 2020 ; Paudel, 2020 ; Peimani and Kamalipour, 2021 ; Rapanta et al., 2020 ; Watermeyer et al., 2021 ). These changes had undoubtedly profound impacts on the academic discourse and everyday practices of teaching. Teachers’ motivations for maintaining effective online teaching during the lockdown were diverse and complex, and therefore, learning outcomes were difficult to be guaranteed. Yu et al. ( 2021 ) examined how innovative teaching could be continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly by learning domain-specific knowledge and skills. The results confirmed that during the lockdown teachers who had studied online teaching methods improved their teaching skills and ICT (information and communication technology) efficacy.

Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) claim that due to the COVID-19 lockdown, educational institutions might cause major interruptions in students’ learning process. Disruption appeared not only in elaborating new knowledge but also in assessment. Given the proof of the significance of exams and tests for learning, educators had to consider postponing rather than renounce assessments. Akar and Coskun ( 2020 ) found that innovative teaching had a slight but positive relationship with creativity. From their point of view, it was not necessarily a consequence of shifting offline teaching to online platforms. Innovative teaching and digital technology were not granted and their impact on student’s performance or teachers’ grading practices is still unclear. The present research aimed to analyse students’ attainment during the COVID-19 pandemic by using student performance data. We focused on the relationship between participation in online courses and dropout decisions, which is connected to teachers’ grading. Examining how grades changed during the lockdown could give us an interesting insight into the educational inequality caused by online education regarding the scholarship system based on student’s grades.

Research questions

We know very little about the effects of transitioning to online education on student dropout and teachers’ grading practices. Even less information is available on the relationship between COVID-19 and dropout, so it is worth a discussion due to the existing controversial and interesting studies on students’ performance. This article gives a suggestion on how the scholarship system could be changed and how we could avoid inequality caused by online education. There is a scholarship system in Hungary that provides financial support to full-time programme students, based on their academic achievement.

Another issue we discuss in this article is dropping out from university programmes, which is a crucial issue worldwide. Between 2010 and 2016 at a large public university in Europe (over 30,000 students) the overall attrition rate is 30%, with the Faculty of Informatics having the worst results (60%) but nowadays these figures are more promising (30|40%). These days at least 800,000 computer scientists may be needed in Europe (Europa.eu, 2015 ), but it seems to be a worldwide issue (Borzovs et al., 2015 ; Ohland et al., 2008 ) to retain students.

This study focuses on the effects of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ dropout and performance in Hungary. Although the manuscript addresses academic dropout, other issues such as inequality or accessibility are also covered in the research. The aim of the paper is therefore to investigate the following questions:

It is inconclusive whether the COVID-19 pandemic had negative effects on students’ performance, which is why we claim that

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant difference in grade point averages between students who participated in online education and those in on-campus education in the second semester of their studies.

Academic achievement (in both traditional and online learning settings) can be measured by accomplishing a specific result in an online assignment and is commonly expressed in terms of a grade point average (GPA; Lounsbury et al., 2005 ; Richardson et al., 2012 ; Wang, 2010 ). According to meta-analyses, GPA is one of the best predictors of dropout (Richardson et al., 2012 ; Broadbent and Poon, 2015 ).

Hypothesis 2: In some subjects (Basic Mathematics practice, Programming, Imperative Programming lecture + practice, Functional Programming, Object-oriented Programming practice + lecture, Algorithms and Data Structures lecture + practice, Discrete Mathematics practice and Analysis practice), it was easier to obtain a passing grade in online education.

Hypothesis 3: More of the students who participated in online education dropped out than those who received on-campus education.

Difficulty and differential analysis of subjects

In the examined higher education system, a BSc programme has six semesters and every subject is graded on a five-point scale, where 1 means fail, and grades from 2 to 5 mean pass, with 5 being the best grade. In the analysis only the final grades were counted in each subject. It is important to see that in order to achieve better grades (or obtain sufficient knowledge), a subject really needs differentiation. It is worth examining the subjects of the various courses because—although there are grades—there is some kind of expected knowledge or skill that the subject should measure. Students are expected to develop these competencies or at least reach an expected level by the end of the semester. To find out whether this kind of competency actually exists (and was developed during online education) and whether the subjects measure this kind of competency, Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis was used to examine the subjects included in the computer science BSc programme. The aim of IRT analysis modelling is to bring the difficulty of the subjects and the ability of the students to the same scale (GRM, Forero and Maydeu-Olivares, 2009 ; Rasch, 1960 ). We had already successfully applied a special IRT model in order to analyse the effects of a student retention programme. In order to prevent student dropout, in a large public university in Europe, a prevention and promotion programme was added to the bachelor’s programme and an education reform was also implemented. In most education systems students have to collect 30 credits per semester by successfully completing 8|10 subjects. We conducted an analysis using data science techniques and the most difficult subjects were identified. As a result, harder subjects were removed, and more introductory courses were built into the curriculum of the first year. A further action—as an intervention—was added to a computer science degree programme: all theoretical lectures became compulsory to attend. According to the results, the dropout level decreased by 28%. The most important benefit of the education reform was that most subjects had become accomplishable (Takács et al., 2021 ). Footnote 1

Hypothesis 1 claims that the online transition due to COVID-19 during the second semester of the 2019 academic year did not result in a change in the requirement system of the subjects. Hypothesis 2 claims that essentially the same expectations were formulated by teachers. In contrast, the way teachers evaluate students necessarily changed. A subject with a given difficulty could be passed by a student with the same ability level with a given probability. Obviously, all subjects that had been less difficult were more likely to be correctly passed than more difficult subjects. The analysis was performed using the IRT, based on the STATA15 software package.

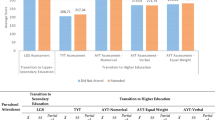

In the study, 862 students were involved in the bachelor’s computer science programme. There were 438 (415) students who started on-campus education in 2018 and 447 students who started on-campus education in 2019, but from March 2020 they participated in online education (Table 1 ). Table 1 shows the result of Hypothesis 1: The grade point average of students who participated in online education (2.5) was lower than that of students who participated in on-campus education (3.3). Table 1 also shows that 447 students participated in online education and only 19 dropped out; 438 students started on-campus education and 50 dropped out. We can conclude that there was no significant difference between students’ dropping out who participated in online education and those who received on-campus education (Hypothesis 3). Note: We can conclude that the grade point average of students who participated in online education (2.5) was lower than that of students who participated in on-campus education (3.3) (Hypothesis 1). On the other hand, there was no significant difference between the drop-out rate of students’ who participated in online education and that of those who received on-campus education (Hypothesis 3). These case numbers make it unnecessary to apply any statistical evidence because the result is obvious.

The subjects were examined by fitting a 2-parameter IRT model to them (scale 1–5 with grades, assuming an ordinal model using the STATA15 programme). ‘Grades’ mean the final grade of the subjects. The STATA15.0 software package was used for the analysis, and the Graded Response Model version of the Ordered item models was chosen from the IRT procedures (GRM; Forero and Maydeu-Olivares, 2009 ).

During the procedure, we examined two parameters: the difficulty of the items and the slope. We took into account those subjects for which the subject matter of the subject remained the same over the years, or the exams did not change substantially (exam grade, according to the same assessment criteria). However, it is important to note that obviously, not the same students completed the assignments each year.

The study involved the following subjects (only professional subjects were considered):

Mathematical Foundations

Programming

Computer Systems lecture+practice

Imperative Programming

Functional Programming

Object-oriented Programming lecture + practice

Algorithms and Data Structures I. lecture

Algorithms and Data Structures I. practice

Discrete Mathematics I. lecture

Discrete Mathematics I. practice

Analysis I. L

Analysis I. P

Examination of slope and difficulty coefficients

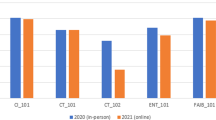

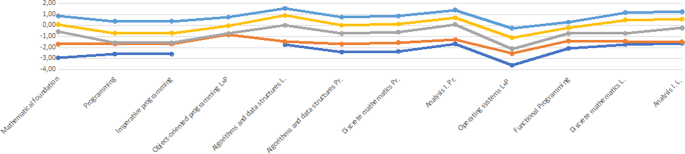

In this section, we examine Table 2 . As a first step, it is crucial to understand the slope indices of the given objects in different years, whether they change from one year to another. Table 2 shows the result of Hypothesis 2: In most subjects (Basic Mathematics practice, Programming, Imperative Programming lecture + practice, Functional Programming, Object-oriented Programming practice+lecture, Algorithms and Data Structures lecture + practice, Discrete Mathematics practice, and Analysis practice), it was easier to obtain a passing grade in online education.

Two parametric procedures were applied: each subject has a difficulty index and a slope.

While if the student’s ability falls short of the difficulty, the denominator of the fraction will increase, so the probability that the student will be able to pass the exam will increase—they will earn a good grade (Fig. 1 ).

Difficulty levels of the subjects in 2018 and 2019 academic year.

Instead of introducing the whole subject network, we introduce a typical subject that was analysed using the IRT. The analyses of the subject of Discrete Mathematics enable us to adequately illustrate the classic phenomenon that arose. The complete analysis of the subjects can be found in Table 2 .

The period before 2019 and after 2019 are shown separately in the table, as at the beginning of 2020 the lockdown took place when online education was introduced to all students so it had an impact on academic achievement. We presupposed that it had manifested itself in the subjects’ completing difficulty and in their ability to differentiate.

Discrete mathematics I. practice

As far as the Discrete Mathematics subject is regarded, we can observe a slope of high value above 3 (sometimes 4) before and after 2019, which means that the subject had strong differentiating abilities both before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is a debate in the literature on how the performance of students changed during online education. Whereas Said ( 2021 ) found no difference in students’ performance before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study by Iglesias-Pradas et al. ( 2021 ) showed an increase in students’ academic performance in distance education. Gonzalez et al. ( 2020 ) predicted better results during online education than in the case of on-campus education. This study partly confirmed their result because more students tried taking the exams. However, they could not perform better as predicted by Gonzalez et al. ( 2020 ) because among computer science students those who participated in online education obtained lower grade point averages than those who participated in on-campus education. According to our results, grade point averages differed substantially between the two examined groups (Hypothesis 1). It can be seen that there are no significant differences in the study groups in terms of dropout after the first year of studies, and the number of students affected was not substantially higher/lower. There are no significant differences in dropout rates between students participating in on-campus or online education (Hypothesis 3).

The result above is crucial; however, the implications and prospective steps based on this result are even more important.

It can be seen that with the introduction of online education, more teaching and learning strategies became available for certain subjects. Teachers’ grading strategies as well as their intentions when giving grades can be assumed as the possible reasons behind the grades. These strategies on both sides (teachers’ and students’) may have appeared during online education.

There were basically two types of changes regarding the grades for the different subjects:

The difficulty associated with the particular grade of the subject in online education decreased for each value on a scale of 1–5 for a given subject (Hypothesis 2). This means that even failing (grade 1) was easier (students preferred to try the exam even if they were unprepared), or even obtaining other passing grades was easier, too. It should be noted that the examined phenomenon cannot have a negative slope (typically not 0), because a slope of 0 means that there is ½ of a probability (regardless of ability) that a student passes a given exam. Fortunately, this is not the case, so we can assume that all slopes are positive.

(a) Behind this strategy, in the case of grade 1, it can be assumed that in online education students’ general strategy was to register for the exam and try it even if unprepared in contrast to the on-campus student who would not take the exam if s/he was unprepared.

(b) It seems that it became easier to obtain a passing grade. Behind this phenomenon, strategies can be assumed from both faculty members' and students’ sides. In case of failing the exam, it makes no sense to talk about the strategy of the teacher, because the teacher was more likely to give a passing grade or even a better grade for less knowledge. In general, the thresholds for obtaining the grade were lower in all cases. This could have been illustrated by the following subjects: Basic Mathematics practice, Programming, Imperative Programming lecture + practice, Functional Programming, Object-oriented Programming practice + lecture, Algorithms and Data Structures lecture + practice, Discrete Mathematics practice and Analysis practice.

Analysing further the subjects by IRT modelling, we saw that it was easier to obtain lower grades (grades 1, 2 and 3). However, in the case grade 4 or 5, it appears that it was more difficult to obtain them due to the prevalence of the higher requirements of the subjects.

(a) The insufficient grades’ (i.e. grade 1) lower level of difficulty (shown by the IRT model) clearly showed that there was no substantial difference in this respect compared to obtaining insufficient grades during the on-campus or online education period.

(b) The results showed that obtaining good grades (4 or 5) became more difficult during online education. It can be assumed that students participating in online education require some kind of help from education management in order to compensate for the disadvantages posed by distance learning because they got worse grades and worse average grade points as compared to on-campus students.

In the following, we examine what strategies faculty members and students may apply considering the difficulty of each grade of the subjects (left column of Table 2 ) showed a decreasing trend.

From the students’ point of view, isolation could result in students being involved in studying more effectively. Consequently, the time spent on the elaboration of the subjects may increase (Wang et al., 2013 ) compared to in-class education and by using available materials, textbooks, practice assignments, students could devote extra energy to subjects, which may result in better exam grades.

From the teachers’ point of view, teachers might want to offer some ‘compensation’ at exams due to non-traditional teaching. In light of this, they are likely to ask a ‘slightly easier’ question, adapt them to the practice tasks, or even lower the exam requirements, e.g., lowering the score limits by 1-2 points more favourable, or accepting answers that would not be accepted in other circumstances.

Note that these two strategies may have been present at the same time: the teacher perceived increased student contribution during the semester, for example, greater activity in online classes, and therefore, provided them with some reward by giving better final grades after taking into consideration their overall performance during the semester.

Please note that both narratives could appear at the same time.

It is also important to see that although grade point averages shifted, the shift was not necessarily drastic, and dropout rates did not improve. It may also be legitimate that there were individual characteristics that caused the difference in the grade point average.

From the student’s point of view, it could also mean that they were prepared in the same way in online education as in in-class education for exams. However, the same strategy did not necessarily result in better grades in the upper segment (obtaining 4 or 5).

The teacher determined the minimum level of requirements, either for mid-term achievements or final assignments and communicated it clearly to the students. How to obtain a passing grade was clear to the students. However, how to obtain good and excellent grades would have required more serious preparation and self-directed learning in online settings.

It is important to see that subjects, where it was more difficult to obtain better grades, were mainly theoretical ones (e.g.: lectures). They were tested mostly by oral exams where it was not possible to use additional materials, they had to answer directly to the questions. In this respect, teachers’ explanations, for example, could lead to very serious shortcomings in the case of knowledge transfer as well as the transfer of the same levels of the previous examination systems. This could result in lower achievement in areas where teachers’ explanations would have been necessary. Students had a harder time bridging the online-offline gap.

Education management issues

In the higher education system analysed, students receive a scholarship according to their grade point average achievement. It is calculated based on the average of the final grades received at the end of the semester and the credits earned. It is worth considering that for online systems, credit-weighted averages will not necessarily show students’ real knowledge. This also results in serious problems when it comes to rewarding students’ performance with a scholarship, where multiple types of educational models may conflict.

This is because whether students can successfully complete a subject differs greatly in an online education system but subjects seem to have become fundamentally easier.

Thus, different education systems (in-class education and online education) can lead to different grading results, so it is not advisable to apply the same scholarship system because it can be fundamentally unfair (some fields can become easier or more difficult).

The results of this study imply that COVID-19 had various effects on the education sector. The results are discussed in connection with the introduction of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of dropouts. The teachers who were involved in this study were the same during online education and on-campus education. This is the reason why we can conclude that the results also seem to suggest that teachers tried to compensate for the negative effects of the pandemic by bringing in pedagogical strategies aimed at ensuring that students could more easily obtain passing grades in examinations. Similarly, according to Mendoza et al. ( 2021 ), the failures of online education had a direct impact on student’s performance and learning.

This study found that students achieved better results during in-class education, which offers interesting implications for teaching practice. The results suggest that organizational support and flexible structures are needed in order to adapt teaching to the new circumstances set by the crisis. Higher education institutions should pay careful attention to developing students’ skills as well as to seeking ways to quickly respond to environmental changes while sustaining the delivery of high-quality education.

In the literature review, contradictory results were found for students’ performance during online education; therefore, this result contends previous literature and should be further explored.

A substantial difference in grade point averages can be found between the two examined groups. The first hypothesis was confirmed: students who participated in on-campus education obtained better grade point averages than students of online education. The teachers declared the minimum level of requirement and communicated it to the students quite clearly. It is a thought-provoking result that for online education, credit-weighted grade point averages would not necessarily show real knowledge well.

The second hypothesis was also proved because some subjects became easier to pass in online education, at least obtaining a passing grade. Online education facilitated students’ strategies e.g., creating an agenda of studying was essential to maintain effective and continuous learning.

The third hypothesis was not confirmed because significant differences in dropout rates were not found between the students who participated in online education and on-campus education. The dropout rate remained nearly unchanged between students who participated in online education (19 students dropped out), and students who participated in on-campus education (50 students dropped out). Introducing online education was effective or at least not harmful in terms of dropout because the dropout rate remained unchanged, compared to the previous year.

The results suggest that regarding dropout rates, there was no significant difference between online and on-campus education. The result suggests several assumptions: e.g.: the teachers had been more indulgent, as they also found it more difficult to communicate effectively during the COVID-19 period and were less able to apply with traditional methods. The process of knowledge transfer moved to online platforms and a different kind of interaction could be applied to rely on the online education system.

Limitations of the study and future research

This study proposed research clarifying the impact of the transition to online courses on dropout. The results show that this period did not contribute significantly to the increase in dropouts. Subjects became more achievable during online education. Students who participated in online education reported lower average grade points than students who participated in on-campus education. Consequently, on-campus students could win better scholarships than students who participated in online education because of better grades.

Several other factors e.g., whether students have met in person in the past, could affect the dropout and grade point averages which were not taken into consideration in this research. In the future, it is recommended to measure students’ current level of knowledge, how much they can adapt to online education, and how they would react in the next similar crisis.

Even though this study presents interesting results, the authors believe that the conclusions derived from them should be interpreted carefully. It allows both researchers and teachers to develop further methods to examine students’ strategies in online education during the COVID-19 period. Future research should be extended with additional variables. Data analysis techniques should also be taken into consideration in order to evaluate the academic profile of students who dropped out in previous years. Limitations include that analysis does not entirely reflect the true engagement of students in the education system because only the first two semesters were examined.

The results of this study open new lines of similar research. It is hoped that other researchers will consider examining the potential impact of COVID-19 on educational planning and scholarship systems. The results of this study can further be validated by considering a wider study that would collect both quantitative and qualitative data to give a deeper understanding of the effects of this epidemic.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

For a detailed explanation of the method see Takács et al. ( 2021 ).

Abilleira MP, Rodicio-García M-L, Ríos-de Deus MP, Mosquera-González MJ (2021) Technostress in Spanish University teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617650

Adedoyin OB, Soykan E (2020) Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact Learn Environ 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Akar I, Karabulut Coskun B (2020) Exploring the relationship between creativity and cyberloafing of prospective teachers. Think Skills Creativity 38:100724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100724

Article Google Scholar

Andrew A, Cattan S, Costa-Dias M, Farquharson C, Kraftman L, Krutikova S, Phimister A, Sevilla A (2020) Learning during the lockdown: real-time data on children’s experiences during home learning. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Google Scholar

Bean JP, Metzner BS (1985) A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Rev Educ Res 55(4):485–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170245 . JSTOR

Bayrakdar S, Guveli A (2020) Inequalities in home learning and schools’ provision of distance teaching during school closure of COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2020-09. University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), Colchester

Belloc F, Maruotti A, Petrella L (2011) How individual characteristics affect university students drop-out: a semiparametric mixed-effects model for an Italian case study. J Appl Stat 38(10):2225–2239. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2010.545373

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Bol T (2020) Inequality in homeschooling during the Corona crisis in the Netherlands. First results from the LISS Panel. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/hf32q . Accessed 10 Nov 2021

Borzovs J, Niedrite L, Solodovnikova D (2015) Factors affecting attrition among first year computer science students: the case of University of Latvia. In: Edmund Teirumnieks (ed) Proceedings of the international scientific and practical conference on environment, technology and resources, Rezekne Academy of Technologies, vol 3. p. 36

Braxton JM, Hirschy AS (2004) Reconceptualizing antecedents of social integration in student departure. In: Yorke M, Longden B (Eds.) Retention and student success in higher education. MPG Books, Bodmin, Great Britain, pp. 89–102

Broadbent J, Poon WL (2015) Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: a systematic review. Internet High Educ 27:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

Brown N, Te Riele K, Shelley B, Woodroffe J (2020) Learning at home during COVID-19: effects on vulnerable young Australians. Independent rapid response report. University of Tasmania, Peter Underwood Centre for Educational Attainment, Hobart

Burgess S, Sievertsen HH (2020) Schools, skills, and learning: the impact of COVID-19 on education, VoxEu.org. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education . Accessed 11 Nov 2021

Cabrera L, Bethencourt JT, Pérez PA, Afonso MG (2006) El problema del abandono de los estudios universitarios. Rev Electrón Invest Eval Educ 12:171–203

Carr S (2000) As distance education comes of age, the challenge is keeping the students. Chron High Educ 46:23

Clark AE, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R (2021) Compensating for academic loss: online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Econ Rev 68:101629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101629

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Daniels LM, Goegan LD, Parker PC (2021) The impact of COVID-19 triggered changes to instruction and assessment on university students’ self-reported motivation, engagement and perceptions. Soc Psychol Educ 24(1):299–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09612-3

Daumiller M, Rinas R, Hein J, Janke S, Dickhäuser O, Dresel M (2021) Shifting from face-to-face to online teaching during COVID-19: The role of university faculty achievement goals for attitudes towards this sudden change, and their relevance for burnout/engagement and student evaluations of teaching quality. Comput Hum Behav 118:106677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106677

Davis NL, Gough M, Taylor LL (2019) Online teaching: advantages, obstacles and tools for getting it right. J Teach Travel Tour 19(3):256–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2019.1612313

Di Pietro G (2006) Regional labour market conditions and university dropout rates: evidence from Italy. Reg Stud 40(6):617–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600868770

Dumford AD, Miller AL (2018) Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement. J Comput High Educ 30(3):452–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z

Engzell P, Frey A, Verhagen MD (2021) Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(17). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118

Europa.eu. (2015) European Commission—Press release—Commission says yes to first successful European Citizens’ Initiative. Resource document. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_14_277 . Accessed 5 Nov 2020

Forero CG, Maydeu-Olivares A (2009) Estimation of IRT graded response models: limited versus full information methods. Psychol Methods 14(3):275–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015825

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gamage KAA, Silva EKde, Gunawardhana N (2020) Online delivery and assessment during COVID-19: safeguarding academic integrity. Educ Sci 10(11):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110301

Gonzalez T, de la Rubia MA, Hincz KP, Comas-Lopez M, Subirats L, Fort S, Sacha GM (2020) Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE 15(10):e0239490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239490

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Iglesias-Pradas S, Hernández-García Á, Chaparro-Peláez J, Prieto JL (2021) Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study. Comput Hum Behav 119:106713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106713

Jovanovic J, Mirriahi N, Gašević D, Dawson S, Pardo A (2019) Predictive power of regularity of pre-class activities in a flipped classroom. Comput Educ 134:156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.011

Levy Y (2007) Comparing dropouts and persistence in e-learning courses. Comput Educ 48(2):185–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.12.004

Lounsbury JW, Huffstetler BC, Leong FT, Gibson LW (2005) Sense of identity and collegiate academic achievement. J College Student Dev 46(5):501–514. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0051

Mendoza D, Cejas M, Rivas G, Varguillas C (2021) Anxiety as a prevailing factor of performance of university mathematics students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Sci J 23(2):94–113. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2021-2-94-113

Molins-Ruano P, Sevilla C, Santini S, Haya PA, Rodríguez P, Sacha GM (2014) Designing videogames to improve students’ motivation. Comput Hum Behav 31:571–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.013

Morris LV, Wu S-S, Finnegan CL (2005) Predicting retention in online general education courses. Am J Distance Educ 19(1):23–36. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15389286ajde1901_3

Nagrecha S, Dillon JZ, Chawla NV (2017) MOOC dropout prediction: lessons learned from making pipelines interpretable. In: Rick Barrett, Rick Cummings (eds) Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion. International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, Perth, WA, Republic and Canton of Genova, pp. 351–359

Nistor N, Neubauer K (2010) From participation to dropout: quantitative participation patterns in online university courses. Comput Educ 55(2):663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.026

Ohland MW, Sheppard SD, Lichtenstein G, Eris O, Chachra D, Layton RA (2008) Persistence, engagement, and migration in engineering programs. J Eng Educ 97(3):259–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2008.tb00978.x

OECD (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on student equity and inclusion: supporting vulnerable students during school closures and school re-openings. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-student-equity-and-inclusion-supporting-vulnerable-students-during-school-closures-and-school-re-openings-d593b5c8/

Pacansky-Brock M, Vincent-Layton K (2020) Humanizing online teaching to equitize higher ed. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33218.94402

Pascarella ET, Terenzini PT (1983) Predicting voluntary freshman year persistence/withdrawal behavior in a residential university: a path analytic validation of Tinto’s model. J Educ Psychol 75(2):215–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.2.215

Palvia S, Aeron P, Gupta P, Mahapatra D, Parida R, Rosner R, Sindhi S (2018) Online education: worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. J Global Inf Technol Manag 21(4):233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2018.1542262

Patterson B, McFadden C (2009) Attrition in online and campus degree programs. Online J Distance Learn Adm 12(2). https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer122/patterson122.html

Paudel P (2020) Online education: benefits, challenges and strategies during and after COVID-19 in higher education. Int J Stud Educ 3(2):70–85. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijonse.32

Peimani N, Kamalipour H (2021) Online education and the COVID-19 outbreak: a case study of online teaching during lockdown. Educ Sci 11(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020072

Rahiem MDH (2021) Remaining motivated despite the limitations: University students’ learning propensity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children Youth Serv Rev 120:105802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105802

Rapanta C, Botturi L, Goodyear P, Guàrdia L, Koole M (2020) Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 Crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit Sci Educ 2(3):923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Rasch G (1960) Probabilistic models for some intelligence and achievement tests. Danish Institute for Educational Research, Copenhagen, Denmark

Reason RD (2009) Review of the book evaluating faculty performance: a practical guide to assessing teaching, research, and service. Rev High Educ 32(2):288–289. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.0.0043

Richardson M, Abraham C, Bond R (2012) Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 138(2):353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

Rovai AP (2003) In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. Internet High Educ 6(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(02)00158-6

Said EGR (2021) How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect higher education learning experience? An empirical investigation of learners’ academic performance at a University in a Developing Country. Adv Hum–Comput Interact 2021:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6649524

Serdyukov P, Hill R (2013) Flying with clipped wings: are students independent in online college classes? J Res Innov Teach 6(1):54–67

Stommel J (2013) Decoding digital pedagogy, part. 2: (Un)Mapping the terrain. Hybrid Pedagog. https://hybridpedagogy.org/decoding-digital-pedagogy-pt-2-unmapping-the-terrain/

Takács R, Kárász JT, Takács S, Horváth Z, Oláh A (2021) Applying the Rasch model to analyze the effectiveness of education reform in order to decrease computer science students’ dropout. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00725-w . Springer Nature

Terenzini PT, Reason RD (2005) Parsing the first year of college: rethinking the effects of college on students. The Association for the Study of Higher Education, Philadelphia, p. 630

Tinto V (1975) Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev Educ Res 45:89–125

Tinto V (2012) Completing college: rethinking institutional action. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Wang C (2010) Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in web-based courses. https://etd.auburn.edu//handle/10415/2256

Wang C-H, Shannon DM, Ross ME (2013) Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning. Distance Educ 34(3):302–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835779

Watermeyer R, Crick T, Knight C, Goodall J (2021) COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. High Educ 81(3):623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Whittle M, Rampton J (2020) Towards a 2030 vision on the future of universities in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. http://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a3cde934-12a0-11eb-9a54-01aa75ed71a1/

Willging PA, Johnson SD (2019) Factors that influence students’ decision to dropout of online courses. J Asynchronous Learn Netw 13(3):13

Yu H, Liu P, Huang X, Cao Y (2021) Teacher online informal learning as a means to innovative teaching during home quarantine in the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 12:2480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.596582

Download references

Acknowledgements

The described article was carried out as part of the EFOP 3.4.3-16-2016-00011 project in the framework of the Széchenyi 2020 programme. The realization of these projects is supported by the European Union, co-financed by the European Social Fund.

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Rita Takács & Zoltán Horváth

Department of General Psychology and Methodology, Institute of Psychology, Budapest, Hungary

Szabolcs Takács

Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, Budapest, Hungary

Doctoral School of Education, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Judit T. Kárász

Institute of Education, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Doctoral School of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Attila Oláh

Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TR contributed to the design of the study and data interpretation. As principal author, she coordinated the writing process of the manuscript. KJ and TS are researchers that study the dropout phenomenon across higher education, and therefore have participated on each phase of this research. OA and HZ have largely contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and consequently to the understanding of the phenomenon. Every author have played a remarkable role in the writing of this article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rita Takács .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

The Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology of Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary approved of the ethical permission, which was registered under the following number: 75/2020 / P / ET. The study protocol was designed and executed in compliance with the code of ethics set out by the university in which the research was conducted, as required by the Helsinki Declaration.

Consent to participate and consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The data were anonymized before analysis and publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Takács, R., Takács, S., Kárász, J.T. et al. The impact of the first wave of COVID-19 on students’ attainment, analysed by IRT modelling method. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 127 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01613-1

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2021

Accepted : 08 March 2023

Published : 25 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01613-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Student’s experiences with online teaching following COVID-19 lockdown: A mixed methods explorative study

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Nursing and Health Promotion, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Primary and Secondary Teacher Education, Faculty of Education and International Studies, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Roles Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

- Kari Almendingen,

- Marianne Sandsmark Morseth,

- Eli Gjølstad,

- Asgeir Brevik,

- Christine Tørris

- Published: August 31, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250378

- Reader Comments

The COVID-19 pandemic lead to a sudden shift to online teaching and restricted campus access.

To assess how university students experienced the sudden shift to online teaching after closure of campus due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methods

Students in Public Health Nutrition answered questionnaires two and 12 weeks (N = 79: response rate 20.3% and 26.6%, respectively) after the lockdown in Norway on 12 March 2020 and participated in digital focus group interviews in May 2020 (mixed methods study).

Findings and discussion

Two weeks into the lockdown, 75% of students reported that their life had become more difficult and 50% felt that learning outcomes would be harder to achieve due to the sudden shift to online education. Twelve weeks into the lockdown, the corresponding numbers were 57% and 71%, respectively. The most pressing concerns among students were a lack of social interaction, housing situations that were unfit for home office purposes, including insufficient data bandwidth, and an overall sense of reduced motivation and effort. The students collaborated well in digital groups but wanted smaller groups with students they knew rather than being randomly assigned to groups. Most students agreed that pre-recorded and streamed lectures, frequent virtual meetings and student response systems could improve learning outcomes in future digital courses. The preference for written home exams over online versions of previous on-campus exams was likely influenced by student’s familiarity with the former. The dropout rate remained unchanged compared to previous years.

The sudden shift to digital teaching was challenging for students, but it appears that they adapted quickly to the new situation. A lthough the concerns described by students in this study may only be representative for the period right after campus lockdown, the study provide the student perspective on a unique period of time in higher education.

Citation: Almendingen K, Morseth MS, Gjølstad E, Brevik A, Tørris C (2021) Student’s experiences with online teaching following COVID-19 lockdown: A mixed methods explorative study. PLoS ONE 16(8): e0250378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250378

Editor: Mohammed Saqr, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, SWEDEN

Received: September 30, 2020; Accepted: April 6, 2021; Published: August 31, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Almendingen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused extraordinary challenges in the global education sector [ 1 , 2 ]. Most countries temporarily closed educational institutions in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus and reduce infections [ 3 ]. In Norway, the move to online teaching and learning methods accelerated as a consequence of the physical closure of universities and university colleges on 12 March 2020 [ 4 ]. Education is better implemented through active, student-centered learning strategies, as opposed to traditional educator-centered pedagogies [ 5 , 6 ]. At the time of the COVID-19 outbreak, the decision to boost the use of active student-centered learning methods and digitalisation had already been made at both the governmental and institutional levels [ 7 , 8 ] because student-active learning (such as use of student response systems and flipping the classroom) increase motivation and improve learning outcomes [ 5 , 7 , 9 ]. However, the implementation of this insight was lagging behind. Traditional educator-centered pedagogies dominated higher education in Norway prior to the lockdown, and only 30% of academic teachers from higher institutions reported having any previous experience with online teaching [ 4 ]. Due to the COVID-19 lockdown, most educators had to change their approaches to most aspects of their work overnight: teaching, assessment, supervision, research, service and engagement [ 4 , 10 ].

Bachelor’s and master’s in Public Health Nutrition (PHN) represents two small-sized programmes at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet). PHN is defined as ‘the application of nutrition and public health principles to design programs, systems, policies, and environments that aims to improve or maintain the optimal health of populations and targeted groups’ [ 11 , 12 ]. Traditional teaching methods dominated on both programs during winter 2020. Following the lockdown, online learning for the continuation of academic activities and the prevention of dropouts from study programmes in higher education were given the highest priority. Due to an extraordinary effort by both the administrative and academic staff, digital alternatives to the scheduled on-campus academic activities were offered to PHN students already in the first week following lockdown. The scheduled on-campus lectures were mainly offered as live-streamed plenary lectures lasting 30–45 minutes, mainly using the video conferencing tool Zoom. Throughout the spring semester educators received training in digital teaching from the institution and increasingly made use of online student response systems (such as Padlet and Mentimeter) as well as tools to facilitate digital group-work (Zoom/Microsoft Teams). Non-theoretical lectures (e.g. cooking classes), were cancelled, and face-to-face exams were re-organized into digital alternatives in order to ensure normal teaching operations. Several small tweaks were employed to minimize dropout. There was no time for coordinating the different courses with regards to the types of online teaching activities, exams and assessments. Social media, i.e Facebook, and SMS were the primary communication channels the first week after lockdown. The use of learning management systems (LMS) Canvas and digital assessment system, Inspera, remained mainly unchanged. Due to the new situation, the deadline for the submission of bachelor theses was postponed by 48 hours. In addition, bachelor students submitting their thesis where given permission to use the submission deadline for the deferred exam in August as their ordinary exam deadline. The deadline for the submission of master theses was extended by one week, but all planned master exams were completed by the end of June, including oral examinations using Zoom instead of the traditional face-to-face examinations on campus. Even though most of the new online activities where put in place with limited regard for subtle nuances of pedagogical theory, and did not allow for much student involvement, the dropout rate from PHN programs remained unchanged compared to previous years. PHN is a small-sized education with close follow up of students. However, although the students experienced a digital revolution overnight, we know little about how they experienced the situation after the university closed for on-campus activities.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to assess how Norwegian PHN students experienced the shift to digital teaching following campus lockdown. Students were also asked to provide feedback on what might improve the learning outcomes in future online lectures and courses.

Design and sampling

This study utilised a mixed methods cross-sectional design, where quantitative and qualitative methods complemented each other. An invitation to participate was sent out to 79 eligible students via multiple channels (Facebook, Teams, Zoom, LMS Canvas, SMS), with several reminders. The only eligibility criteria was being a student in PHN during spring 2020. All students received the quantitative survey. Due to few students eligible for each focus group interview, all who wanted to participate were interviewed/included. The invited students were in their second-year (n = 17) and third-year (n = 28) bachelor’s and first-year (n = 13) and second-year (n = 21) master’s programme at PHN in the Faculty of Health Sciences at OsloMet. The response rate was 16/79 (20.3%) and 21/79 (26.6%). Two focus group interviews were scheduled in each class (a total of 8) but only 4 interviews were conducted. The research team was heterogeneously composed of members with both pedagogical and health professional backgrounds.

Online questionnaire

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first “corona” study at our Faculty. No suitable national or international questionnaire had been developed and /or validated by March 2020. Hence, online questionnaires for the present study were designed virtually ‘over-night’. The questions were however based on experiences from a large-scale interprofessional learning course using the blended learning approach at OsloMet [ 13 , 14 ] and specific experiences that academic staff in Norway reported during the first week of teaching during the lockdown [ 4 ]. The questionnaires were based on an anonymous self-administrated web survey ‘Nettskjema’ [ 15 ]. ‘Nettskjema’ is a Norwegian tool for designing and conducting online surveys with features that are customised for research purposes. It is easy to use, and the respondents can submit answers from a browser on a computer, mobile phone or tablet. During the first week after lockdown, the questionnaire was sent out to university colleagues and head of studies and revised accordingly. The questionnaires were deliberately kept short because the response rate is generally low in student surveys [ 16 ]. Ideally, we should have pretested and validated the questionnaires, but this was not possible within the short-time frame after lockdown. Items were measured on a five-level ordinal scale (Likert scale 0–5). The two forms contained both numerical and open questions, permitting both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The first questionnaire was sent out to the students on 25 March 2020 (two weeks after the closure of university campus; students were asked to submit their answers during the period from 12 March until the link was closed at Easter Holiday), and the second questionnaire was sent on 3 June 2020 (12 weeks after closure; students were asked to submit their answers during the period after Easter and until the end of the spring semester). The questionnaires were distributed as web links embedded in the LMS Canvas application. Because live-streamed lectures were offered primarily through Zoom during the first weeks, students were not asked about interactive digital teaching and tools in the first questionnaire. At the end of both questionnaires, the students were asked what they believed could improve the learning experience in future online education. The qualitative part consisted of text answers to open questions from the two electronic questionnaires.