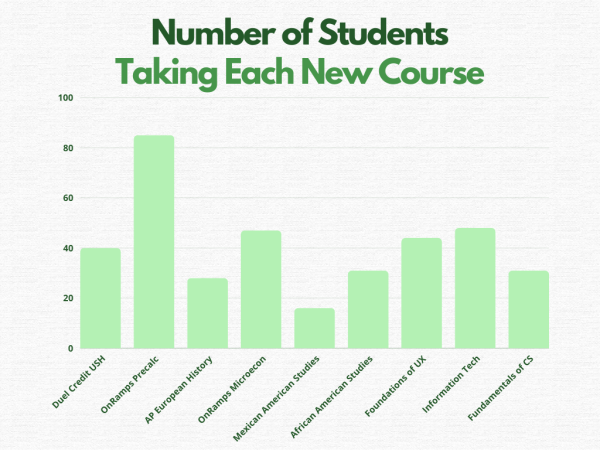

- September 9 Eleven courses added to Bellaire

- August 15 Mighty Cardinal Band attends summer camp to practice show

- July 17 International Thespian Festival

- June 15 Future Problem Solvers place second in Texas with community project

- May 28 Engi-near the finish line

Three Penny Press

Students spend three times longer on homework than average, survey reveals

Sonya Kulkarni and Pallavi Gorantla | Jan 9, 2022

Graphic by Sonya Kulkarni

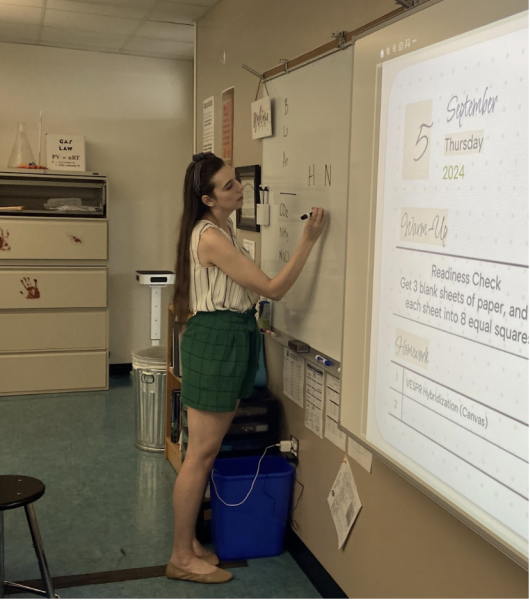

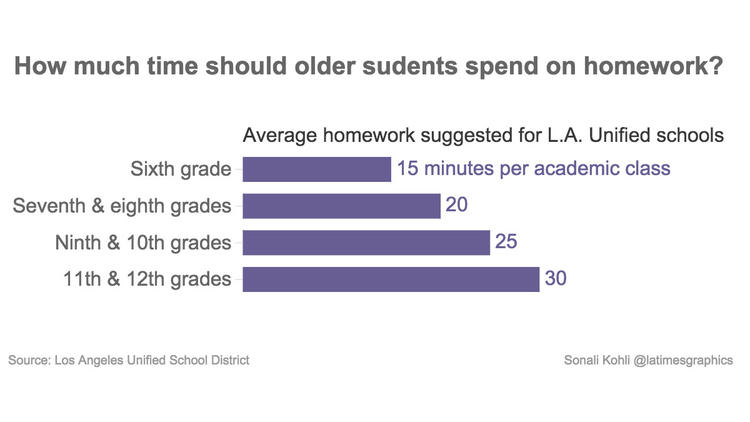

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association have suggested that a healthy number of hours that students should be spending can be determined by the “10-minute rule.” This means that each grade level should have a maximum homework time incrementing by 10 minutes depending on their grade level (for instance, ninth-graders would have 90 minutes of homework, 10th-graders should have 100 minutes, and so on).

As ‘finals week’ rapidly approaches, students not only devote effort to attaining their desired exam scores but make a last attempt to keep or change the grade they have for semester one by making up homework assignments.

High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by the Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals. A survey of approximately 200 Bellaire High School students revealed that some students spend over three times this number.

The demographics of this survey included 34 freshmen, 43 sophomores, 54 juniors and 54 seniors on average.

When asked how many hours students spent on homework in a day on average, answers ranged from zero to more than nine with an average of about four hours. In contrast, polled students said that about one hour of homework would constitute a healthy number of hours.

Junior Claire Zhang said she feels academically pressured in her AP schedule, but not necessarily by the classes.

“The class environment in AP classes can feel pressuring because everyone is always working hard and it makes it difficult to keep up sometimes.” Zhang said.

A total of 93 students reported that the minimum grade they would be satisfied with receiving in a class would be an A. This was followed by 81 students, who responded that a B would be the minimum acceptable grade. 19 students responded with a C and four responded with a D.

“I am happy with the classes I take, but sometimes it can be very stressful to try to keep up,” freshman Allyson Nguyen said. “I feel academically pressured to keep an A in my classes.”

Up to 152 students said that grades are extremely important to them, while 32 said they generally are more apathetic about their academic performance.

Last year, nine valedictorians graduated from Bellaire. They each achieved a grade point average of 5.0. HISD has never seen this amount of valedictorians in one school, and as of now there are 14 valedictorians.

“I feel that it does degrade the title of valedictorian because as long as a student knows how to plan their schedule accordingly and make good grades in the classes, then anyone can be valedictorian,” Zhang said.

Bellaire offers classes like physical education and health in the summer. These summer classes allow students to skip the 4.0 class and not put it on their transcript. Some electives also have a 5.0 grade point average like debate.

Close to 200 students were polled about Bellaire having multiple valedictorians. They primarily answered that they were in favor of Bellaire having multiple valedictorians, which has recently attracted significant acclaim .

Senior Katherine Chen is one of the 14 valedictorians graduating this year and said that she views the class of 2022 as having an extraordinary amount of extremely hardworking individuals.

“I think it was expected since freshman year since most of us knew about the others and were just focused on doing our personal best,” Chen said.

Chen said that each valedictorian achieved the honor on their own and deserves it.

“I’m honestly very happy for the other valedictorians and happy that Bellaire is such a good school,” Chen said. “I don’t feel any less special with 13 other valedictorians.”

Nguyen said that having multiple valedictorians shows just how competitive the school is.

“It’s impressive, yet scary to think about competing against my classmates,” Nguyen said.

Offering 30 AP classes and boasting a significant number of merit-based scholars Bellaire can be considered a competitive school.

“I feel academically challenged but not pressured,” Chen said. “Every class I take helps push me beyond my comfort zone but is not too much to handle.”

Students have the opportunity to have off-periods if they’ve met all their credits and are able to maintain a high level of academic performance. But for freshmen like Nguyen, off periods are considered a privilege. Nguyen said she usually has an hour to five hours worth of work everyday.

“Depending on the day, there can be a lot of work, especially with extra curriculars,” Nguyen said. “Although, I am a freshman, so I feel like it’s not as bad in comparison to higher grades.”

According to the survey of Bellaire students, when asked to evaluate their agreement with the statement “students who get better grades tend to be smarter overall than students who get worse grades,” responders largely disagreed.

Zhang said that for students on the cusp of applying to college, it can sometimes be hard to ignore the mental pressure to attain good grades.

“As a junior, it’s really easy to get extremely anxious about your GPA,” Zhang said. “It’s also a very common but toxic practice to determine your self-worth through your grades but I think that we just need to remember that our mental health should also come first. Sometimes, it’s just not the right day for everyone and one test doesn’t determine our smartness.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

‘A cathartic experience’

A Reagan rollercoaster

Do what you love

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Cydney Tinsley

Walking through time

Eleven courses added to Bellaire

Mighty Cardinal Band attends summer camp to practice show

International Thespian Festival

Future Problem Solvers place second in Texas with community project

Engi-near the finish line

Comments (8).

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Anonymous • Jul 16, 2024 at 3:27 pm

didnt realy help

Anonymous • Nov 21, 2023 at 10:32 am

It’s not really helping me understand how much.

josh • May 9, 2023 at 9:58 am

Kassie • May 6, 2022 at 12:29 pm

Im using this for an English report. This is great because on of my sources needed to be from another student. Homework drives me insane. Im glad this is very updated too!!

Kaylee Swaim • Jan 25, 2023 at 9:21 pm

I am also using this for an English report. I have to do an argumentative essay about banning homework in schools and this helps sooo much!

Izzy McAvaney • Mar 15, 2023 at 6:43 pm

I am ALSO using this for an English report on cutting down school days, homework drives me insane!!

E. Elliott • Apr 25, 2022 at 6:42 pm

I’m from Louisiana and am actually using this for an English Essay thanks for the information it was very informative.

Nabila Wilson • Jan 10, 2022 at 6:56 pm

Interesting with the polls! I didn’t realize about 14 valedictorians, that’s crazy.

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Your content has been saved!

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

- Share article

Editor’s note: This is an adapted excerpt from You, Your Child, and School: Navigate Your Way to the Best Education ( Viking)—the latest book by author and speaker Sir Ken Robinson (co-authored with Lou Aronica), published in March. For years, Robinson has been known for his radical work on rekindling creativity and passion in schools, including three bestselling books (also with Aronica) on the topic. His TED Talk “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” holds the record for the most-viewed TED talk of all time, with more than 50 million views. While Robinson’s latest book is geared toward parents, it also offers educators a window into the kinds of education concerns parents have for their children, including on the quality and quantity of homework.

The amount of homework young people are given varies a lot from school to school and from grade to grade. In some schools and grades, children have no homework at all. In others, they may have 18 hours or more of homework every week. In the United States, the accepted guideline, which is supported by both the National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association, is the 10-minute rule: Children should have no more than 10 minutes of homework each day for each grade reached. In 1st grade, children should have 10 minutes of daily homework; in 2nd grade, 20 minutes; and so on to the 12th grade, when on average they should have 120 minutes of homework each day, which is about 10 hours a week. It doesn’t always work out that way.

In 2013, the University of Phoenix College of Education commissioned a survey of how much homework teachers typically give their students. From kindergarten to 5th grade, it was just under three hours per week; from 6th to 8th grade, it was 3.2 hours; and from 9th to 12th grade, it was 3.5 hours.

There are two points to note. First, these are the amounts given by individual teachers. To estimate the total time children are expected to spend on homework, you need to multiply these hours by the number of teachers they work with. High school students who work with five teachers in different curriculum areas may find themselves with 17.5 hours or more of homework a week, which is the equivalent of a part-time job. The other factor is that these are teachers’ estimates of the time that homework should take. The time that individual children spend on it will be more or less than that, according to their abilities and interests. One child may casually dash off a piece of homework in half the time that another will spend laboring through in a cold sweat.

Do students have more homework these days than previous generations? Given all the variables, it’s difficult to say. Some studies suggest they do. In 2007, a study from the National Center for Education Statistics found that, on average, high school students spent around seven hours a week on homework. A similar study in 1994 put the average at less than five hours a week. Mind you, I [Robinson] was in high school in England in the 1960s and spent a lot more time than that—though maybe that was to do with my own ability. One way of judging this is to look at how much homework your own children are given and compare it to what you had at the same age.

Many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all.

There’s also much debate about the value of homework. Supporters argue that it benefits children, teachers, and parents in several ways:

- Children learn to deepen their understanding of specific content, to cover content at their own pace, to become more independent learners, to develop problem-solving and time-management skills, and to relate what they learn in school to outside activities.

- Teachers can see how well their students understand the lessons; evaluate students’ individual progress, strengths, and weaknesses; and cover more content in class.

- Parents can engage practically in their children’s education, see firsthand what their children are being taught in school, and understand more clearly how they’re getting on—what they find easy and what they struggle with in school.

Want to know more about Sir Ken Robinson? Check out our Q&A with him.

Q&A With Sir Ken Robinson

Ashley Norris is assistant dean at the University of Phoenix College of Education. Commenting on her university’s survey, she says, “Homework helps build confidence, responsibility, and problem-solving skills that can set students up for success in high school, college, and in the workplace.”

That may be so, but many parents find it difficult to help their children with subjects they’ve not studied themselves for a long time, if at all. Families have busy lives, and it can be hard for parents to find time to help with homework alongside everything else they have to cope with. Norris is convinced it’s worth the effort, especially, she says, because in many schools, the nature of homework is changing. One influence is the growing popularity of the so-called flipped classroom.

In the stereotypical classroom, the teacher spends time in class presenting material to the students. Their homework consists of assignments based on that material. In the flipped classroom, the teacher provides the students with presentational materials—videos, slides, lecture notes—which the students review at home and then bring questions and ideas to school where they work on them collaboratively with the teacher and other students. As Norris notes, in this approach, homework extends the boundaries of the classroom and reframes how time in school can be used more productively, allowing students to “collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique [each other’s work], and share those experiences.”

Even so, many parents and educators are increasingly concerned that homework, in whatever form it takes, is a bridge too far in the pressured lives of children and their families. It takes away from essential time for their children to relax and unwind after school, to play, to be young, and to be together as a family. On top of that, the benefits of homework are often asserted, but they’re not consistent, and they’re certainly not guaranteed.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How much time should you spend studying? Our ‘Goldilocks Day’ tool helps find the best balance of good grades and well-being

Senior Research Fellow, Allied Health & Human Performance, University of South Australia

Professor of Health Sciences, University of South Australia

Disclosure statement

Dot Dumuid is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship GNT1162166 and by the Centre of Research Excellence in Driving Global Investment in Adolescent Health funded by NHMRC GNT1171981.

Tim Olds receives funding from the NHMRC and the ARC.

University of South Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

For students, as for all of us, life is a matter of balance, trade-offs and compromise. Studying for hours on end is unlikely to lead to best academic results. And it could have negative impacts on young people’s physical, mental and social well-being.

Our recent study found the best way for young people to spend their time was different for mental health than for physical health, and even more different for school-related outcomes. Students needed to spend more time sitting for best cognitive and academic performance, but physical activity trumped sitting time for best physical health. For best mental health, longer sleep time was most important.

It’s like a game of rock, paper, scissors with time use. So, what is the sweet spot, or as Goldilocks put it, the “just right” amount of study?

Read more: Back to school: how to help your teen get enough sleep

Using our study data for Australian children aged 11 and 12, we are developing a time-optimisation tool that allows the user to define their own mental, physical and cognitive health priorities. Once the priorities are set, the tool provides real-time updates on what the user’s estimated “Goldilocks day” looks like.

More study improves grades, but not as much as you think

Over 30 years of research shows that students doing more homework get better grades. However, extra study doesn’t make as much difference as people think. An American study found the average grades of high school boys increased by only about 1.5 percentage points for every extra hour of homework per school night.

What these sorts of studies don’t consider is that the relationship between time spent doing homework and academic achievement is unlikely to be linear. A high school boy doing an extra ten hours of homework per school night is unlikely to improve his grades by 15 percentage points.

There is a simple explanation for this: doing an extra ten hours of homework after school would mean students couldn’t go to bed until the early hours of the morning. Even if they could manage this for one day, it would be unsustainable over a week, let alone a month. In any case, adequate sleep is probably critical for memory consolidation .

Read more: What's the point of homework?

As we all know, there are only 24 hours in a day. Students can’t devote more time to study without taking this time from other parts of their day. Excessive studying may become detrimental to learning ability when too much sleep time is lost.

Another US study found that, regardless of how long a student normally spent studying, sacrificing sleep to fit in more study led to learning problems on the following day. Among year 12s, cramming in an extra three hours of study almost doubled their academic problems. For example, students reported they “did not understand something taught in class” or “did poorly on a test, quiz or homework”.

Excessive study could also become unhelpful if it means students don’t have time to exercise. We know exercise is important for young people’s cognition , particularly their creative thinking, working memory and concentration.

On the one hand, then, more time spent studying is beneficial for grades. On the other hand, too much time spent studying is detrimental to grades.

We have to make trade-offs

Of course, how young people spend their time is not only important to their academic performance, but also to their health. Because what is the point of optimising school grades if it means compromising physical, mental and social well-being? And throwing everything at academic performance means other aspects of health will suffer.

US sleep researchers found the ideal amount of sleep for for 15-year-old boys’ mental health was 8 hours 45 minutes a night, but for the best school results it was one hour less.

Clearly, to find the “Goldilocks Zone” – the optimal balance of study, exercise and sleep – we need to think about more than just school grades and academic achievement.

Read more: 'It was the best five years of my life!' How sports programs are keeping disadvantaged teens at school

Looking for the Goldilocks Day

Based on our study findings , we realised the “Goldilocks Day” that was the best on average for all three domains of health (mental, physical and cognitive) would require compromises. Our optimisation algorithm estimated the Goldilocks Day with the best overall compromise for 11-to-12-year-olds. The breakdown was roughly:

10.5 hours of sleep

9.5 hours of sedentary behaviour (such as sitting to study, chill out, eat and watch TV)

2.5 hours of light physical activity (chores, shopping)

1.5 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (sport, running).

We also recognised that people – or the same people at different times — have different priorities. Around exam time, academic performance may become someone’s highest priority. They may then wish to manage their time in a way that leads to better study results, but without completely neglecting their mental or physical health.

To better explore these trade-offs, we developed our time-use optimisation tool based on Australian data . Although only an early prototype, the tool shows there is no “one size fits all” solution to how young people should be spending their time. However, we can be confident the best solutions will involve a healthy balance across multiple daily activities.

Just like we talk about the benefits of a balanced diet, we should start talking about the benefits of balanced time use. The better equipped young people and those supporting them are to find their optimal daily balance of sleep, sedentary behaviours and physical activities, the better their learning outcomes will be, without compromising their health and well-being.

- Mental health

- Physical activity

- Children's mental health

- Children and sleep

- Children's well-being

- children's physical health

- Sleep research

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

Associate Director, Post-Award, RGCF

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

- Newsletters

How Much Time Should Be Spent On Homework?

- Dr. Sam Goldstein , Sydney S. Zentall

At the elementary level we suggest that homework is brief, at your child’s ability level and involve frequent, voluntary and high interest activities. Young students require high levels of feedback and/or supervision to help them complete assignments correctly. Accurate homework completion is influenced by your child’s ability, the difficulty of the task and the amount of feedback your child receives. When assigning homework, your child’s teachers may struggle to create a balance at this age between ability, task difficulty and feedback. Unfortunately, there are no simple guiding principles. We can assure you, however, that your input and feedback on a nightly basis is an essential component in helping your child benefit from the homework experience. In first through third grade, students should receive one to three assignments per week, taking them no more than fifteen to twenty minutes. In fourth through sixth grade, students should receive two to four assignments per week, lasting between fifteen and forty-five minutes. At this age, the primarily goal of homework is to help your child develop the independent work and learning skills that will become critical in the higher grades. In the upper grades, the more time spent on homework the greater the achievement gains.

For students in middle and high school grades there are greater overall benefits from time engaged in practicing and thinking about school work. These benefits do not appear to depend as much upon immediate supervision or feedback as they do for elementary students. In seventh through ninth grade we recommend students receive three to five sets of assignments per week, lasting between forty-five and seventy-five minutes per set. In high school students will receive four to five sets of homework per week, taking them between seventy-five and 150 minutes per set to complete.

As children progress through school, homework and the amount of time engaged in homework increases in importance. Due to the significance of homework at the older age levels, it is not surprising that there is more homework assigned. Furthermore, homework is always assigned in college preparatory classes and assigned at least three quarters of the time in special education and vocational training classes. Thus at any age, homework may indicate our academic expectations of children.

Regardless of the amount of homework assigned, many students unsuccessful or struggling in school, spend less rather than more time engaged in homework. It is not surprising that students spending less time completing homework may eventually not achieve as consistently as those who complete their homework. Does this mean that time devoted to homework is the key component necessary for achievement? We are not completely certain. Some American educators have concluded that if students in America spent as much time doing homework as students in Asian countries they might perform academically as well. It is tempting to assume such a cause and effect relationship. However, this relationship appears to be an overly simple conclusion. We know that homework is important as one of several influential factors in school success. However, other variables, including student ability, achievement, motivation and teaching quality influence the time students spend with homework tasks. Many students and their parents have told us they experience less difficulty being motivated and completing homework in classes in which they enjoyed the subject, the instruction, the assignments and the teachers.

The benefits from homework are the greatest for students completing the most homework and doing so correctly. Thus, students who devote time to homework are probably on a path to improved achievement. This path also includes higher quality instruction, greater achievement motivation and better skill levels.

This column is excerpted and condensed from, Seven Steps to Homework Success: A Family Guide for Solving Common Homework Problems by Sydney S. Zentall, Ph.D. and Sam Goldstein, Ph.D. (1999, Specialty Press, Inc.).

- More Resources

General Articles

Homework Articles

Forensic Updates

Golf Articles

How Much Homework is Too Much?

When redesigning a course or putting together a new course, faculty often struggle with how much homework and readings to assign. Too little homework and students might not be prepared for the class sessions or be able to adequately practice basic skills or produce sufficient in-depth work to properly master the learning goals of the course. Too much and some students may feel overwhelmed and find it difficult to keep up or have to sacrifice work in other courses.

A common rule of thumb is that students should study three hours for each credit hour of the course, but this isn’t definitive. Universities might recommend that students spend anywhere from two or three hours of study or as much as six to nine hours of study or more for each course credit hour. A 2014 study found that, nationwide, college students self reported spending about 17 hours each week on homework, reading and assignments. Studies of high school students show that too much homework can produce diminishing returns on student learning, so finding the right balance can be difficult.

There are no hard and fast rules about the amount of readings and homework that faculty assign. It will vary according to the university, the department, the level of the classes, and even other external factors that impact students in your course. (Duke’s faculty handbook addresses many facets of courses, such as absences, but not the typical amount of homework specifically.)

To consider the perspective of a typical student that might be similar to the situations faced at Duke, Harvard posted a blog entry by one of their students aimed at giving students new to the university about what they could expect. There are lots of readings, of course, but time has to be spent on completing problem sets, sometimes elaborate multimedia or research projects, responding to discussion posts and writing essays. Your class is one of several, and students have to balance the needs of your class with others and with clubs, special projects, volunteer work or other activities they’re involved with as part of their overall experience.

The Rice Center for Teaching Excellence has some online calculators for estimating class workload that can help you get a general understanding of the time it may take for a student to read a particular number of pages of material at different levels or to complete essays or other types of homework.

To narrow down your decision-making about homework when redesigning or creating your own course, you might consider situational factors that may influence the amount of homework that’s appropriate.

Connection with your learning goals

Is the homework clearly connected with the learning goals of your students for a particular class session or week in the course? Students will find homework beneficial and valuable if they feel that it is meaningful . If you think students might see readings or assignments as busy work, think about ways to modify the homework to make a clearer connection with what is happening in class. Resist the temptation to assign something because the students need to know it. Ask yourself if they will actually use it immediately in the course or if the material or exercises should be relegated to supplementary material.

Levels of performance

The type of readings and homework given to first year students will be very different from those given to more experienced individuals in higher-level courses. If you’re unsure if your readings or other work might be too easy (or too complex) for students in your course, ask a colleague in your department or at another university to give feedback on your assignment. If former students in the course (or a similar course) are available, ask them for feedback on a sample reading or assignment.

Common practices

What are the common practices in your department or discipline? Some departments, with particular classes, may have general guidelines or best practices you can keep in mind when assigning homework.

External factors

What type of typical student will be taking your course? If it’s a course preparing for a major or within an area of study, are there other courses with heavy workloads they might be taking at the same time? Are they completing projects, research, or community work that might make it difficult for them to keep up with a heavy homework load for your course?

Students who speak English as a second language, are first generation students, or who may be having to work to support themselves as they take courses may need support to get the most out of homework. Detailed instructions for the homework, along with outlining your learning goals and how the assignment connects the course, can help students understand how the readings and assignments fit into their studies. A reading guide, with questions prompts or background, can help students gain a better understanding of a reading. Resources to look up unfamiliar cultural references or terms can make readings and assignments less overwhelming.

If you would like more ideas about planning homework and assignments for your course or more information and guidance on course design and assessment, contact Duke Learning Innovation to speak with one of our consultants .

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

About the Author

More Stories

Reporting on Parenthood Has Made Me Nervous About Having Kids

The Economic Principle That Helps Me Order at Restaurants

How Much Time Do College Students Spend on Homework

by Jack Tai | Oct 9, 2019 | Articles

Does college life involve more studying or socializing?

Find out how much time college students need to devote to their homework in order to succeed in class.

We all know that it takes hard work to succeed in college and earn top grades.

To find out more about the time demands of studying and learning, let’s review the average homework amounts of college students.

HowtoLearn.com expert, Jack Tai, CEO of OneClass.com shows how homework improves grades in college and an average of how much time is required.

How Many Hours Do College Students Spend on Homework?

Classes in college are much different from those in high school.

For students in high school, a large part of learning occurs in the classroom with homework used to support class activities.

One of the first thing that college students need to learn is how to read and remember more quickly. It gives them a competitive benefit in their grades and when they learn new information to escalate their career.

Taking a speed reading course that shows you how to learn at the same time is one of the best ways for students to complete their reading assignments and their homework.

However, in college, students spend a shorter period in class and spend more time learning outside of the classroom.

This shift to an independent learning structure means that college students should expect to spend more time on homework than they did during high school.

In college, a good rule of thumb for homework estimates that for each college credit you take, you’ll spend one hour in the classroom and two to three hours on homework each week.

These homework tasks can include readings, working on assignments, or studying for exams.

Based upon these estimates, a three-credit college class would require each week to include approximately three hours attending lectures and six to nine hours of homework.

Extrapolating this out to the 15-credit course load of a full-time student, that would be 15 hours in the classroom and 30 to 45 hours studying and doing homework.

These time estimates demonstrate that college students have significantly more homework than the 10 hours per week average among high school students. In fact, doing homework in college can take as much time as a full-time job.

Students should keep in mind that these homework amounts are averages.

Students will find that some professors assign more or less homework. Students may also find that some classes assign very little homework in the beginning of the semester, but increase later on in preparation for exams or when a major project is due.

There can even be variation based upon the major with some areas of study requiring more lab work or reading.

Do College Students Do Homework on Weekends?

Based on the quantity of homework in college, it’s nearly certain that students will be spending some of their weekends doing homework.

For example, if each weekday, a student spends three hours in class and spends five hours on homework, there’s still at least five hours of homework to do on the weekend.

When considering how homework schedules can affect learning, it’s important to remember that even though college students face a significant amount of homework, one of the best learning strategies is to space out study sessions into short time blocks.

This includes not just doing homework every day of the week, but also establishing short study blocks in the morning, afternoon, and evening. With this approach, students can avoid cramming on Sunday night to be ready for class.

What’s the Best Way to Get Help with Your Homework?

In college, there are academic resources built into campus life to support learning.

For example, you may have access to an on-campus learning center or tutoring facilities. You may also have the support of teaching assistants or regular office hours.

That’s why OneClass recommends a course like How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It which gives a c hoice to support your learning.

Another choice is on demand tutoring.

They send detailed, step-by-step solutions within just 24 hours, and frequently, answers are sent in less than 12 hours.

When students have on-demand access to homework help, it’s possible to avoid the poor grades that can result from unfinished homework.

Plus, 24/7 Homework Help makes it easy to ask a question. Simply snap a photo and upload it to the platform.

That’s all tutors need to get started preparing your solution.

Rather than retyping questions or struggling with math formulas, asking questions and getting answers is as easy as click and go.

Homework Help supports coursework for both high school and college students across a wide range of subjects. Moreover, students can access OneClass’ knowledge base of previously answered homework questions.

Simply browse by subject or search the directory to find out if another student struggled to learn the same class material.

Related articles

NEW COURSE: How to Read a Book in a Day and Remember It

Call for Entries Parent and Teacher Choice Awards. Winners Featured to Over 2 Million People

All About Reading-Comprehensive Instructional Reading Program

Parent & Teacher Choice Award Winner – Letter Tracing for Kids

Parent and Teacher Choice Award Winner – Number Tracing for Kids ages 3-5

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Kids

One Minute Gratitude Journal

Parent and Teacher Choice Award winner! Cursive Handwriting for Teens

Make Teaching Easier! 1000+ Images, Stories & Activities

Prodigy Math and English – FREE Math and English Skills

Recent Posts

- 5 Essential Techniques to Teach Sight Words to Children

- 7 Most Common Reading Problems and How to Fix Them

- Best Program for Struggling Readers

- 21 Interactive Reading Strategies for Pre-Kindergarten

- 27 Education Storybook Activities to Improve Literacy

Recent Comments

- Glenda on How to Teach Spelling Using Phonics

- Dorothy on How to Tell If You Are an Employee or Entrepreneur

- Pat Wyman on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- kapenda chibanga on 5 Best Focus and Motivation Tips

- Jennifer Dean on 9 Proven Ways to Learn Anything Faster

College Homework: What You Need to Know

- April 1, 2020

Samantha "Sam" Sparks

- Future of Education

Despite what Hollywood shows us, most of college life actually involves studying, burying yourself in mountains of books, writing mountains of reports, and, of course, doing a whole lot of homework.

Wait, homework? That’s right, homework doesn’t end just because high school did: part of parcel of any college course will be homework. So if you thought college is harder than high school , then you’re right, because in between hours and hours of lectures and term papers and exams, you’re still going to have to take home a lot of schoolwork to do in the comfort of your dorm.

College life is demanding, it’s difficult, but at the end of the day, it’s fulfilling. You might have had this idealized version of what your college life is going to be like, but we’re here to tell you: it’s not all parties and cardigans.

How Many Hours Does College Homework Require?

Here’s the thing about college homework: it’s vastly different from the type of takehome school activities you might have had in high school.

See, high school students are given homework to augment what they’ve learned in the classroom. For high school students, a majority of their learning happens in school, with their teachers guiding them along the way.

In college, however, your professors will encourage you to learn on your own. Yes, you will be attending hours and hours of lectures and seminars, but most of your learning is going to take place in the library, with your professors taking a more backseat approach to your learning process. This independent learning structure teaches prospective students to hone their critical thinking skills, perfect their research abilities, and encourage them to come up with original thoughts and ideas.

Sure, your professors will still step in every now and then to help with anything you’re struggling with and to correct certain mistakes, but by and large, the learning process in college is entirely up to how you develop your skills.

This is the reason why college homework is voluminous: it’s designed to teach you how to basically learn on your own. While there is no set standard on how much time you should spend doing homework in college, a good rule-of-thumb practiced by model students is 3 hours a week per college credit . It doesn’t seem like a lot, until you factor in that the average college student takes on about 15 units per semester. With that in mind, it’s safe to assume that a single, 3-unit college class would usually require 9 hours of homework per week.

But don’t worry, college homework is also different from high school homework in how it’s structured. High school homework usually involves a take-home activity of some kind, where students answer certain questions posed to them. College homework, on the other hand, is more on reading texts that you’ll discuss in your next lecture, studying for exams, and, of course, take-home activities.

Take these averages with a grain of salt, however, as the average number of hours required to do college homework will also depend on your professor, the type of class you’re attending, what you’re majoring in, and whether or not you have other activities (like laboratory work or field work) that would compensate for homework.

Do Students Do College Homework On the Weekends?

Again, based on the average number we provided above, and again, depending on numerous other factors, it’s safe to say that, yes, you would have to complete a lot of college homework on the weekends.

Using the average given above, let’s say that a student does 9 hours of homework per week per class. A typical semester would involve 5 different classes (each with 3 units), which means that a student would be doing an average of 45 hours of homework per week. That would equal to around 6 hours of homework a day, including weekends.

That might seem overwhelming, but again: college homework is different from high school homework in that it doesn’t always involve take-home activities. In fact, most of your college homework (but again, depending on your professor, your major, and other mitigating factors) will probably involve doing readings and writing essays. Some types of college homework might not even feel like homework, as some professors encourage inter-personal learning by requiring their students to form groups and discuss certain topics instead of doing take-home activities or writing papers. Again, lab work and field work (depending on your major) might also make up for homework.

Remember: this is all relative. Some people read fast and will find that 3 hours per unit per week is much too much time considering they can finish a reading in under an hour.The faster you learn how to read, the less amount of time you’ll need to devote to homework.

College homework is difficult, but it’s also manageable. This is why you see a lot of study groups in college, where your peers will establish a way for everyone to learn on a collective basis, as this would help lighten the mental load you might face during your college life. There are also different strategies you can develop to master your time management skills, all of which will help you become a more holistic person once you leave college.

So, yes, your weekends will probably be chock-full of schoolwork, but you’ll need to learn how to manage your time in such a way that you’ll be able to do your homework and socialize, but also have time to develop your other skills and/or talk to family and friends.

College Homework Isn’t All That Bad, Though

Sure, you’ll probably have time for parties and joining a fraternity/sorority, even attend those mythical college keggers (something that the person who invented college probably didn’t have in mind). But I hate to break it to you: those are going to be few and far in between. But here’s a consolation, however: you’re going to be studying something you’re actually interested in.

All of those hours spent in the library, writing down papers, doing college homework? It’s going to feel like a minute because you’re doing something you actually love doing. And if you fear that you’ll be missing out, don’t worry: all those people that you think are attending those parties aren’t actually there because they, too, will be busy studying!

About the Author

News & Updates

10 prominent careers to pursue in college, a montessori approach to literacy in private schools, a quick guide to getting into bee keeping.

- College Prep & Testing

- College Search

- Applications & Admissions

- Alternatives to 4-Year College

- Orientation & Move-In

- Campus Involvement

- Campus Resources

- Homesickness

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Transferring

- Residential Life

- Finding an Apartment

- Off-Campus Life

- Mental Health

- Alcohol & Drugs

- Relationships & Sexuality

- COVID-19 Resources

- Paying for College

- Banking & Credit

- Success Strategies

- Majors & Minors

- Study Abroad

- Diverse Learners

- Online Education

- Internships

- Career Services

- Graduate School

- Graduation & Celebrations

- First Generation

- Shop for College

- Academics »

Student Study Time Matters

Vicki nelson.

Most college students want to do well, but they don’t always know what is required to do well. Finding and spending quality study time is one of the first and most important skills that your student can master, but it's rarely as simple as it sounds.

If a student is struggling in class, one of the first questions I ask is, “How much time do you spend studying?”

Although it’s not the only element, time spent studying is one of the basics, so it’s a good place to start. Once we examine time, we can move on to other factors such as how, where, what and when students are studying, but we start with time .

If your student is struggling , help them explore how much time they are spending on schoolwork.

How Much Is Enough?

Very often, a student’s answer to how much time they spend hitting the books doesn’t match the expectation that most professors have for college students. There’s a disconnect about “how much is enough?”

Most college classes meet for a number of “credit hours” – typically 3 or 4. The general rule of thumb (and the definition of credit hour adopted by the Department of Education) is that students should spend approximately 2–3 hours on outside-of-class work for each credit hour or hour spent in the classroom.

Therefore, a student taking five 3-credit classes spends 15 hours each week in class and should be spending 30 hours on work outside of class , or 45 hours/week total.

When we talk about this, I can see on students’ faces that for most of them this isn’t even close to their reality!

According to one survey conducted by the National Survey of Student Engagement, most college students spend an average of 10–13 hours/week studying, or less than 2 hours/day and less than half of what is expected. Only about 11% of students spend more than 25 hours/week on schoolwork.

Why Such a Disconnect?

Warning: math ahead!

It may be that students fail to do the math – or fail to flip the equation.

College expectations are significantly different from the actual time that most high school students spend on outside-of-school work, but the total picture may not be that far off. In order to help students understand, we crunch some more numbers.

Most high school students spend approximately 6 hours/day or 30 hours/week in school. In a 180 day school year, students spend approximately 1,080 hours in school. Some surveys suggest that the average amount of time that most high school students spend on homework is 4–5 hours/week. That’s approximately 1 hour/day or 180 hours/year. So that puts the average time spent on class and homework combined at 1,260 hours/school year.

Now let’s look at college: Most semesters are approximately 15 weeks long. That student with 15 credits (5 classes) spends 225 hours in class and, with the formula above, should be spending 450 hours studying. That’s 675 hours/semester or 1,350 for the year. That’s a bit more than the 1,260 in high school, but only 90 hours, or an average of 3 hours more/week.

The problem is not necessarily the number of hours, it's that many students haven’t flipped the equation and recognized the time expected outside of class.

In high school, students’ 6-hour school day was not under their control but they did much of their work during that time. That hour-or-so a day of homework was an add-on. (Some students definitely spend more than 1 hour/day, but we’re looking at averages.)

In college, students spend a small number of hours in class (approximately 15/week) and are expected to complete almost all their reading, writing and studying outside of class. The expectation doesn’t require significantly more hours; the hours are simply allocated differently – and require discipline to make sure they happen. What students sometimes see as “free time” is really just time that they are responsible for scheduling themselves.

Help Your Student Adjust to College Academics >

How to Fit It All In?

Once we look at these numbers, the question that students often ask is, “How am I supposed to fit that into my week? There aren’t enough hours!”

Again: more math.

I remind students that there are 168 hours in a week. If a student spends 45 hours on class and studying, that leaves 123 hours. If the student sleeps 8 hours per night (few do!), that’s another 56 hours which leaves 67 hours, or at least 9.5 hours/day for work or play.

Many colleges recommend that full-time students should work no more than 20 hours/week at a job if they want to do well in their classes and this calculation shows why.

Making It Work

Many students may not spend 30 or more hours/week studying, but understanding what is expected may motivate them to put in some additional study time. That takes planning, organizing and discipline. Students need to be aware of obstacles and distractions (social media, partying, working too many hours) that may interfere with their ability to find balance.

What Can My Student Do?

Here are a few things your student can try.

- Start by keeping a time journal for a few days or a week . Keep a log and record what you are doing each hour as you go through your day. At the end of the week, observe how you have spent your time. How much time did you actually spend studying? Socializing? Sleeping? Texting? On social media? At a job? Find the “time stealers.”

- Prioritize studying. Don’t hope that you’ll find the time. Schedule your study time each day – make it an appointment with yourself and stick to it.

- Limit phone time. This isn’t easy. In fact, many students find it almost impossible to turn off their phones even for a short time. It may take some practice but putting the phone away during designated study time can make a big difference in how efficient and focused you can be.

- Spend time with friends who study . It’s easier to put in the time when the people around you are doing the same thing. Find an accountability partner who will help you stay on track.

- If you have a job, ask if there is any flexibility with shifts or responsibilities. Ask whether you can schedule fewer shifts at prime study times like exam periods or when a big paper or project is due. You might also look for an on-campus job that will allow some study time while on the job. Sometimes working at a computer lab, library, information or check-in desk will provide down time. If so, be sure to use it wisely.

- Work on strengthening your time management skills. Block out study times and stick to the plan. Plan ahead for long-term assignments and schedule bite-sized pieces. Don’t underestimate how much time big assignments will take.

Being a full-time student is a full-time job. Start by looking at the numbers with your student and then encourage them to create strategies that will keep them on task.