Social Work Practice with Carers

Case Study 1: Eve

Download the whole case study as a PDF file

Eve is a carer for her father, who has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems. She has two children: a son, Matt, who is 17 and has Crohn’s disease, and a daughter, Joanne, who is 15.

This case study considers issues around being a ‘ sandwich carer’ – that is, caring for both a parent and a child – maintaining employment and working with a whole family including family group conferences, as well as the impact of dementia and the role of assistive technology .

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

- One-page profile

- Support plan

Transcript (.pdf, 61KB)

Name : Eve Davies

Gender : Female

Ethnicity : White British

Download resource as a PDF file

First language : English

Religion : None

Eve lives in a town. She has two children, a son, Matt, who is 17 and has Crohn’s disease, and a daughter, Joanne, who is 15. Eve’s mother died four years ago, and her father, Geoff, lives close by. Geoff has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems relating to a heart attack he had two years ago. Eve works part time in an administration role at a local college. She has lost contact with her friends and lost touch with her hobbies (swimming and singing in a choir) because she has prioritised her family.

Matt is at college studying for his A levels. He is frustrated that his illness is interfering with all aspects of his life. Joanne is becoming more withdrawn and resentful as an increasing amount of Eve’s time is taken up with other family members. Geoff has started to neglect himself at home, and is finding it more difficult to carry out daily tasks. Following a social care assessment, he has a befriending service stop by every week and a homecare team each morning to check he’s ok and supervise his medication, which Eve sets up for them. The care agency have reported that there’s a possibility Geoff has been accessing his medication and taking it. Geoff remains adamant that he is fine, and with Eve’s support he can manage.

Eve is feeling stressed and isolated. She wants to increase her working hours for financial reasons, but is unable to as she needs to be available for Geoff. Eve is having problems with sleeping and feels generally run down, and recently has been suffering from stomach pain and nausea. She says that she feels ‘withdrawn from normal life.’ She tried attending a carers’ group but found that listening to other carers’ problems highlighted her own. Instead, she sometimes uses an online forum at night when everyone else is asleep.

Eve was recently referred by her GP for a carer’s assessment. You have been out to see her twice and talked to her children. You have completed the assessment and support plan with her.

Back to Summary

What others like and admire about me

Good mum (mostly!)

I’m very organised

People can count on me

I help people out

I’m a good singer

What is important to me

My kids – I want them to be happy

Family time

Dad staying at home – I promised Mum

My job – people I work with

Health – exercise, sleep!

Just to know I’m not on my own

How best to support me

Listen to me and include me in your network

A bit of ‘me time’ to breathe – see friends, swimming, choir

Be honest about what you can do and do what you say you will

Don’t lumber your problems on me when there’s nothing I can do

Talk to me about me, not just about caring

Let me know who to contact

Don’t give me loads of information

Emails not phone please

Don’t arrange meetings when I’m at work

Help me plan so I can do everything!

Date chronology completed 15 February 2016

Date shared with person 15 February 2016

| 15.02.74 | Evelyn Mary Davies (known as Eve) born in Welsh border town. | |

| 12.04.96 | Married to Eric Sanderson and moved to Moreton. | |

| 26.07.98 | Birth of first child, son, Mathew Eric Sanderson. | |

| 18.09.00 | Birth of second child, daughter, Joanne Rachael Sanderson. | |

| 16.09.03 | Divorced. Reverted to maiden name though children retained their father’s name. | Eve and children remain in the marital home. Eve is proud of how well she has managed, with her part-time post which she enjoys and regular child support from the children’s father. Eve says she was not unduly concerned when initial fortnightly contact between the children and their father began to tail off. The children did not wish to travel to his new location some 50 miles away and he did not make sufficient effort in her view to see them. |

| 03.07.09 | Son, Matt, diagnosed with Crohn’s disease which causes him to frequently need the toilet, and have some faecal incontinence. He has relapses causing dramatic weight loss and frequent hospital admission. | Eve managed the health care and hospital appointments for her son as well as providing reassurance. Eventual diagnosis indicates a need for longer term health service involvement. Eve values the support of school nurse and feels that physically Matt’s illness is under control more now though the stigma and embarrassment of Matt’s illness has begun to take its toll on his emotional wellbeing. |

| 21.01.12 | Eve’s mother, Margaret, died suddenly in her sleep having suffered a heart attack. Eve herself is shocked by her mother’s death and describes her father as struggling to cope with his wife’s sudden death. | Eve now includes her father’s shopping in her weekly shop, prepares his evening meals, helps with laundry and other household chores, juggling this with her own chores and Matt’s health appointments. |

| 19.03.14 | Eve’s father, Geoff, had a heart attack. Hospitalised for two weeks whilst a stent was fitted and his recovery monitored. | His heart attack has left Eve’s father with numerous related health problems. Eve begins to manage of her father’s health appointments alongside management of Matt’s. Over the next year Geoff starts to have memory problems. |

| 16.11.15 | Eve’s father diagnosed with early stage vascular dementia. Social care assessment undertaken. Befriending service and home care provision arranged.

| Mixed service with Eve as main carer for her father, Geoff Davies, and some home care and befriending service provision to Geoff now in place. At this time Eve tried attending a carers’ group but found that listening to other carers’ problems highlighted her own. Instead, she sometimes uses an online forum at night when everyone else is asleep. |

| 29.01.16 | Eve attends her GP surgery as she is regularly feeling nauseous. The GP asked Eve if she is experiencing more stress than usual. Eve expresses concern that her father has started to neglect himself at home, and is finding it more difficult to carry out daily tasks. He gets confused with tasks like making a meal. Eve worries that he doesn’t eat properly. Sometimes he has trouble remembering words and this makes him feel cross. Eve explains that he sometimes now has short bursts of sudden confusion. She finds this frightening and her children do too, which worries her. | Following this discussion with Eve about the pressures on her at the moment and indications of stress causing her physical symptoms, with her agreement the GP has referred Eve for a social care assessment as carer for both her father and her son.

|

| 04.02.16 | Initial visit by social worker. SW sees Eve on her own at home. | SW makes another appointment to continue the assessment at a time when the children are at home to include them in the conversation. |

| 09.02.16 | Second visit to Eve and conversation with her children. | Carer’s assessment and support plan completed. SW arranges with Geoff that he will have an assessment in the next few weeks. |

| 15.02.16 | Paperwork completed. | Sent to Eve. |

Eve’s Ecogram

Name Eve Davies

Address 1 Fir Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z11

Telephone 012345 123456

Email [email protected]

Gender Female

Date of birth 15.2.1974 Age 42

Ethnicity White British

First language English

Religion None

GP Dr Tailor, Parkside Surgery

How would you like us to contact you?

Do you need any support with communication?

About the person/ people I care for

My relationship to this person Daughter

Name Geoff Davies

Address 1 Pine Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z22

Telephone 012345 234567

Gender Male

Date of birth 8.1.1943 Age 73

Religion Baptised C of E

Please tell us about any existing support the person you care for already has in place. This could be home care, visits or support from a community, district or community psychiatric nurse, attending any community groups or day centres, attending any training or adult learning courses, or support from friends and neighbours.

Home care every morning for medication and check up

Befriending service 2 hours a week

My relationship to this person Mother

Name Matt Sanderson

Address 1 Fir Avenue, Moreton, ZZ1 Z22

Date of birth 26.7.1998 Age 17

Goes to college (doing A levels)

GP and nurse at the surgery

Consultant at the hospital

The things I do as a carer to give support

Please use the space below to tell us about the things you do as a carer (including the emotional and practical support you provide such as personal care, preparing meals, supporting the person you care for to stay safe, motivating and re-assuring them, dealing with their medication and / or their finances).

Dad has early stage vascular dementia and numerous health problems relating to a heart attack he had two years ago. He has started to neglect himself at home, and is finding it more and more difficult to carry out daily tasks. He gets confused with cooking or tasks like making a meal. Sometimes Dad has trouble remembering words and this makes him feel cross. On occasion he does experience short bursts of sudden confusion, which can be frightening for other family members.

Following a social care assessment, he has a befriending service stop by every week and a homecare team each morning to check he’s ok and supervise his medication.

This is what I do for Dad:

- Preparing Dad’s medication for the day – setting out in reminder containers

- Greeting care workers in the morning

- Remind Dad about having a wash

- Leave lunch in fridge

- Remind Dad about appointments

- Visit in the evening and cook dinner

- Sort out problems with the care agency

- Do shopping, cleaning, laundry

- Collect medication

- Check for medical appointments/ reviews

- Take Dad to appointments

- Sort out Dad’s mail – pay bills

- Fix things round the house

- Sort out extra care if Matt is in hospital

Matt has Crohn’s disease. He is at college studying for his A levels. He is doing well but his illness does interfere with his life and he can get frustrated about this. He wants good grades to be able to become a journalist and move abroad. It is embarrassing for him that he has to frequently rush to the toilet, and occasionally he is incontinent. Matt has regular relapses. This causes him to lose a lot of weight and he has been in hospital three times in the last year and missed college.

This is what I do for Matt:

- In the morning, make special lunch and ensure that he has his emergency bag (extra clothing, wipes, plastic bag and air freshener)

- Remind him about his weekly blood test appointment.

- Extra washing

- Help with homework

- Transporting Matt to hospital/GP/nurse appointments.

I also look after my daughter Joanne who is 15.

How my caring role impacts on my life

Please use the space below to tell us about the impact your caring role has on your life.

Like all working mums I have a lot on. As I have had to do more for Dad, it has got more difficult to juggle family chores and work.

I want to increase my working hours for financial reasons but I don’t see how I can at the moment, as Dad’s care needs are increasing and I need to be available for him. I’ve had to take some flexible working hours recently to cover last minute changes in arrangements for Dad’s care. I frequently have to take phone calls at work about care arrangements. I am concerned that I won’t be able to keep working and we need the money.

I’m worried that Dad isn’t eating properly. The care agency have reported that the medication audit has shown that Dad might have been taking his medication at the wrong times. Dad doesn’t want to talk about longer term planning and making advanced decisions. He does not want any more social care provision in the house. This really worries me particularly as Dad will need more help as time goes on. Also if Dad suddenly needed a lot more help or I was unwell then I am not sure how we would manage.

I want Matt to be able to manage his illness better so that he is happier and able to do the things he wants. As I have had to spend more time with Dad and Matt, my daughter Joanne has become more distant. She finds it difficult that we need to work around what Matt needs, for example for meals. Joanne has always been helpful but has become more withdrawn and resentful. She has started to hang around with older teenagers, and I’m worried they might be ‘leading her astray’. She has had a few letters from school mentioning poor attendance and a drop in her grades. I feel like I don’t have time at the moment to be a good mum.

I’m having problems with sleeping and feel generally run down, and recently I have had to see the GP about stomach pain and nausea, which she thinks is to do with stress. I feel like I don’t have any time now to just breathe and am withdrawing from normal life. I don’t currently have time to exercise – I used to swim, or to sing in the choir. I’ve also lost contact with friends so I feel quite isolated.

What supports me as a carer?

Please use the space below to tell us about what helps you in your caring role.

I sometimes go on an online carers’ forum at night when everyone else is asleep and that’s quite helpful. I did try attending a carers’ group but it got me down listening to other people’s problems.

Work gives me a bit of a break from caring and my boss has so far been quite supportive with flexible working though I don’t want to push it.

Matt’s nurse at the GP surgery has been really helpful with information and support. Matt gets on with her well.

My feelings and choices about caring

Please use the space below to tell us about how you are feeling and if you would like to change anything about your caring role and your life.

It’s my choice to care for my family and I want to keep on doing that, and be a good mum and a good daughter.

If I knew that Dad was getting the care he needs and that we had a plan for the future then I would manage much better.

At the moment I’m feeling stressed and quite overwhelmed. There’s always something else to sort out. I feel like I don’t have anyone to support me. I miss my Mum and worry about whether I’m looking after my Dad as well as she did.

I want to know my family is ok. I don’t want to stop looking after my kids and my Dad.

I want to be able to manage my different roles at home and at work, and to do things well.

I want to have more time with my children and we want more time as a family.

I would love to increase my hours at work.

I’d like to start swimming and join the choir again. I’d like to see friends sometimes.

I do need more sleep.

Information, advice and support

Let us know what advice or information you feel would help you and what sort of support you think would be beneficial to you in your caring role.

Someone to talk to Dad about getting the care he needs – particularly to ensure he takes the right medication and that he eats enough.

Some help with planning Dad’s care in case there is a crisis, and to plan ahead for what he will need in the future.

Someone to check on Dad when I’m at work.

A break – just to be free without interruptions.

Some back-up so that I am not always on call.

Someone to talk to about how to manage all of this.

Someone for Joanne to talk to if she wants to.

Someone to support Matt to manage his illness so he can achieve his aims.

To be used by social care assessors to consider and record measures which can be taken to assist the carer with their caring role to reduce the significant impact of any needs. This should include networks of support, community services and the persons own strengths. To be eligible the carer must have significant difficulty achieving 1 or more outcomes without support; it is the assessors’ professional judgement that unless this need is met there will be a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing. Social care funding will only be made available to meet eligible outcomes that cannot be met in any other way, i.e. social care funding is only available to meet unmet eligible needs

Date assessment completed 15 February 2016

Social care assessor conclusion

Eve is providing significant support to her father and her two children, one of whom has Crohn’s disease. Eve also works part-time. Eve’s father has some support from home care and a befriending service. Her son has support from health services. Eve is very organised, and juggles chores and work well. However, she says that she is starting to feel increasingly stressed and this is having an impact on her health. She is also quite isolated and has no time at present to have a break from caring. Eve would like to continue supporting her family and increase her working hours, as well as having some time for her own interests. It is important to Eve that her father remains at home and is safe, and that her children are happy. Eve would benefit from support to enable her to manage the demands on her, and to have some time for herself. She would also benefit from some emotional support for her and for her family. This will enable her to continue as a carer and to improve her health and wellbeing.

Eligibility decision Eligible for support

What’s happening next Create support plan

Carry out assessment for Mr Geoff Davies

Completed by

Organisation

Signing this form (for carer)

Please ensure you read the statement below in bold, then sign and date the form.

I understand that completing this form will lead to a computer record being made which will be treated confidentially. The council will hold this information for the purpose of providing information, advice and support to meet my needs. To be able to do this the information may be shared with relevant NHS Agencies and providers of carers’ services. This will also help reduce the number of times I am asked for the same information.

If I have given details about someone else, I will make sure that they know about this.

I understand that the information I provide on this form will only be shared as allowed by the Data Protection Act.

Date of birth 15.2.1974 Age 42

Support plan completed by

Support Plan

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

|

Date of support plan: 15 February 2016

This plan will be reviewed on: 15 February 2017

Signing this form

Eve has given consent to share this support plan with Mr Davies. This support plan will link into his assessment.

Sandwich caring

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to assess adult carers, including parent carers of disabled and other children in need, before the child they care for turns 18, so that they have the information they need to plan for their future. Guidance, advocating a whole family approach, is available to social workers (LGA 2015, SCIE 2015, ADASS/ADCS 2011).

- Carers UK (2012) Sandwich caring

- Circle (2018) Supporting carers to work and care

- Think Local Act Personal (2017) Supporting working carers

- Mumsnet for the Care Quality Commission August (2014) Care Quality Commission: Sandwich Generation Survey Summary Report

- Institute for Public Policy Research (2013) The sandwich generation: older women balancing work and care

- Carers UK (2014) Carers at breaking point

- Blog: Impact of cuts

Carers’ employment

Research shows that both emotional and practical support from social workers are valuable, for example when looking at what was valued by the mothers of transition-age children with mental illness (Gerten and Hensley 2014) and by men as caregivers to the elderly (Collins 2014).

- Skills for Care (2013) Balancing work and care

- Carers UK (2015) Caring and isolation in the workplace

- Carers UK (2014) The case for care leave

- Carers UK (2014) Supporting employees who are caring for someone with dementia

- Carers UK (2013) Supporting working carers

- NIHR (2014) Improving employment opportunities for carers: identifying and sharing good practice

- Department of Health (2015) Pilots to understand how to support carers to stay in paid employment

- Tool 1: Support for carers in employment

Life course and whole family approaches

The whole family approach is a strong theme in the research (LGA 2015) along with relationship based practice (SCIE 2016, Cooper 2015, Wilson et al 2011, Ruch et al 2010). Family group conferencing, along with mediation as whole family approaches, were found to have particular applicability to adult safeguarding social work. (SCIE 2012).

- Beth Johnson Foundation (2014) A life course approach to promoting positive ageing

- SCIE (2012) At a glance 62: Safeguarding adults: Mediation and family group conferences

- Hobbs A and Alonzi A (2013) Mediation and family group conferences in adult safeguarding, Journal of Adult Protection, 15(2) , pp.69-84

- Carers Trust Whole family approach – practice examples

- Tool 2: Family group conferences

Assistive technology

Evidence points to the need for social work teams are to have good information about the support available to carers. National materials offer a valuable resource to social workers seeking to research how to work with their clients and their carers which can be supplemented locally and from the active contributions of the ‘online’ community (Young Sam Oh 2015).

- SCIE (2010) At a glance 24: Ethical issues in the use of telecare

- Carers UK and Tunstall (2013) Potential for Change: Transforming public awareness and demand for health and care technology

- Carers UK and Tunstall (2012) Carers and telecare

- Carers UK (2012) Future care: Care and technology in the 21st century

- SCIE (2010) Telecare videos

- Tool 3: Ethics of assistive technology

Research suggests an assets or strengths based approach to social work support with the person and their family and/or network of support. The Manual for good social work practice (DH 2015) uses a timeline as a model that can underpin how the social worker supports and intervenes, from early preventative measures through various stages of loss towards end-of-life. Three critical points on the timeline – diagnosis, taking up active caring and the decline of the person’s capacity – are identified. It is important for social workers to assess the carers needs, sustain the carers own identity, develop and maintain their network of support and resources, and access financial and legal advice.

- SCIE Dementia Gateway Department of Health (2015) TCSW (2015) A manual for good social work practice: Supporting adults who have dementia , The College of Social Work

- Carers Trust (2014) The Triangle of Care: Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care

- Carers Trust (2013) A Road Less Rocky – Supporting Carers of People with Dementia

- Alzheimer’s Research UK (2015) Dementia in the family: the impact on carers

- Tool 4: Triangle of care – self-assessment for dementia professionals Carers Trust (2014) The Triangle of Care: Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice for Dementia Care (Page 22 Self-assessment tool for organisations)

Tool 1: Support for Carers in Employment

You can use this tool with carers to think about what would support someone to manage work and caring responsibilities.

|

| ||

| Supportive manager

| ||

| Flexible/ special leave arrangements

| ||

| Flexible working hours

| ||

| Remote working

| ||

| Information and support for carers at work

| ||

| High quality, appropriate care and support

| ||

| Support from relatives and friends

| ||

| Services that are available outside working hours

| ||

| Help with coordinating care and support

| ||

| Advice and information about legal & money issues

|

This tool is based on research about what helps carers who are working (Carers UK (2015) Caring and isolation in the workplace).

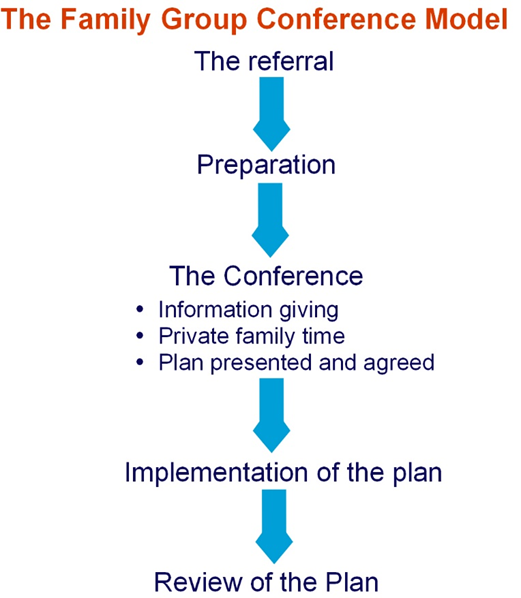

Tool 2: Family Group Conference

This tool sets out the process for a Family Group Conference. You can use it to plan and hold a conference.

The Family Group Conference process

Stage 1: The referral

Whether or not a family group conference takes place is a decision made by the family. Under no circumstances can a family be made or forced to have a family group conference.

Once a referral for a family group conference is made, there will need to be a co-ordinator to liaise with the family.

The co-ordinator helps the family to plan the meeting and chair the meeting. The co-ordinator is different from the referrer and acts as a neutral person. The co-ordinator will not influence the family to make a particular decision but will help them to think about the decisions that need to be made. Families should be offered the opportunity to request a co-ordinator who suitably reflects their ethnicity, language, religion or gender, and the family’s request should be accommodated wherever possible.

Stage 2: Preparation

The co-ordinator organises the meeting in conjunction with the family members and other members of the network. This can include close friends.

- The co-ordinator discusses with the person with care and support needs how they can be helped to participate in the conference and whether they would like a supporter or advocate at the meeting . The supporter/advocate will then meet with them in preparation for the meeting.

- The co-ordinator meets with members of the family network, discusses worries or concerns, including how the family group conference will be conducted, and encourages them to attend.

- the wellbeing concerns which need to be considered at the family group conference. This includes identifying any bottom line about what can, and, importantly, cannot be agreed as part of the plan from the agency’s perspective.

- services that could help.

- The co-ordinator negotiates the date, time and venue for the conference, sends out invitations and makes the necessary practical arrangements.

Stage 3: The conference

The family group conference follows three distinct stages.

a) Information giving

This part of the meeting is chaired by the co-ordinator. They will make sure that everyone is introduced, that everyone present understands the purpose and process of the family group conference and agrees how the meeting will be conducted including, if felt helpful by those present, explicit ground rules. The service providers give information to the family about:

- the reason for the conference;

- information they hold that will assist the family to make the plan;

- information about resources and support they are able to provide;

- any wellbeing concerns that will affect what can be agreed in the plan; and

- what action will be taken if the family cannot make a plan or the plan is not agreed.

The family members may also provide information, ask for clarification or raise questions.

b) Private family time

Agency staff and the co-ordinator are not present during this part of the conference. Family members have time to talk among themselves and come up with a plan that addresses concerns raised. They will identify resources and support which are required from agencies, as well as within the family, to make the plan work.

c) Plan and agreement

When the family has made their plan, the referrer and the co-ordinator meet with the family to discuss and agree the plan including resources.

It is the referrer’s responsibility to agree the plan of action and it is important that this happens on the day of the conference. It should be presumed that the plan must be agreed unless it puts anyone at risk of significant harm. Any reasons for not accepting the plan must be made clear immediately and the family should be given the opportunity to respond to the concerns and change or add to the plan.

It is important to ensure that everyone involved has a clear understanding of what is decided and that their views are understood.

Resources are discussed and agreed with the agency concerned, and it is important that, at this point, timescales and names of those responsible for any tasks are clarified. Contingency plans, monitoring arrangements and how to review the plan also need to be agreed.

The co-ordinator should distribute the plan to family members involved and to the social worker and other information givers/relevant professionals.

1.3.5 Stage Three: Implementation of the Plan

It is essential that everybody involved implements their parts of the plan within agreed timescales and communicate and addresses any problems that arise.

1.3.6 Stage Four: Review of the plan

There should be a clear process for reviewing the implementation of the plan. A review family group conference or other meeting should be offered to the family so they can consider how the plan is working, and to make adjustments or change the plan if necessary.

This information is based largely on the Family Rights Group’s Family Group Conference Process

Tool 3: Ethics of using assistive technology

This tool highlights the ethical issues of using assistive technology. You can use it to consider when assistive technology would be beneficial for someone, and to reflect on the benefits and drawbacks of it more generally.

What are the ethical issues about using assistive technology (AT) to support carers?

This tool is based on SCIE At a glance 24: Ethical issues in the use of telecare

Download The Triangle of Care as a PDF file

The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

The Triangle of Care is a therapeutic alliance between service user, staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports recovery and sustains wellbeing…

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

- Compare CSWE Accredited Online MSW Programs

- Advanced Standing MSW Programs

- Discover HBCU MSW Programs Online & On-Campus

- On-Campus MSW Programs

- Fast Track MSW Programs

- Hybrid MSW Programs

- Full-time online MSW programs

- Part-Time Online MSW Programs

- Online Clinical Social Work Degree Programs (LCSW)

- Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Programs Online

- Online Military Social Work Programs

- Considering a Major in Social Work?

- Ph.D. in Social Work Online

- Schools By State

- Sponsored: Fordham University

- Sponsored: University of Denver

- Sponsored: Simmons University

- Sponsored: Case Western Reserve University

- Sponsored: Howard University

- Sponsored: Simmons University – DSW Online

- How Long Does It Take to Become a Social Worker?

- 2022 Study Guide to the Social Work Licensing Exam

- How to Become a Veterinary Social Worker

- How to Become a LCSW

- How to Become a School Social Worker

- Become a Victim Advocate

- Social Worker Interviews

- Is a Master of Social Work (MSW) worth it?

- Social Work Salaries – How Much Do Social Workers Make?

- Bachelor’s in Psychology Programs Online

- Concentrations in Online MSW Programs

- Social Work: Core Values & Code of Ethics

- Introduction to Social Learning Theory

- Introduction to Systems Theory

- Introduction to Psychosocial Development Theory

- Introduction to Psychodynamic Theory

- Introduction to Social Exchange Theory

- Introduction to Rational Choice Theory

- What is Social Justice?

- What is Social Ecology?

Online MSW Programs / Guide to Careers in Social Work / Geriatric Social Work: A Guide to Social Work with Older Adults

Geriatric Social Work: A Guide to Social Work with Older Adults

In this article:

- What is a Geriatric Social Worker?

How to Become a Geriatric Social Worker

What does a geriatric social worker do, where do geriatric social workers work, the challenges and rewards of gerontological social work, what is a geriatric social worker.

Gerontological social workers, also known as geriatric social workers, coordinate the care of older patients in a variety of settings, including hospitals, community health clinics, long-term and residential health care facilities, hospice settings, and outpatient/daytime health care centers.

The American Geriatrics Society projects that about 30% of Americans ages 65 and over will need geriatric care by 2030 (PDF, 500 KB) . As the need for geriatricians grows, so will the role of social workers in elderly care.

In outpatient settings, geriatric social workers are advocates for the older adults, ensuring they receive the mental, emotional, social and familial support they need, while also connecting them to resources in the community that may provide additional support. In inpatient and residential care settings, they conduct intake assessments to determine patients’ mental, emotional and social needs; collaborate with a team of physicians, nurses, psychologists, case managers and other health care staff to develop and regularly update patient treatment plans; discuss treatment plan options with patients and their families; and manage patient discharges.

This guide features interviews with gerontological social workers. All interviewees were compensated to participate.

Role of Social Workers in Elderly Care

Those who work in geriatric social work help their clients manage psychological, emotional and social challenges by providing counseling and therapy, advising clients’ families about how to best support aging loved ones, serving as the bridge of communication between clients and the rest of the care team, and ensuring that clients receive the services they need if or when they move between inpatient and outpatient treatment programs, in-home care, day treatment programs, and the like.

The role of social workers in elderly care leads to unique opportunities, which include making deep and meaningful connections with clients and their families, changing problematic systems at both the personal and community levels, and the knowledge that their work has a direct positive impact on those in need.

Education Requirements

A bachelor’s degree in social work from an accredited university is the minimum education requirement for those seeking credentials in gerontology . Those who want to become a social worker for older adult clients often seek a Master of Social Work (MSW) with a clinical concentration . These programs help prepare students to become licensed clinical social workers (LCSW). In addition to foundation level social work courses, they focus on the skills needed to provide social work services and treatment to individuals (children, youth and adults) and small groups (couples and families).

Students learn about advanced assessment techniques, diagnosing and treating psychosocial problems, and developing, promoting and restoring mental health and social functioning. Students are also taught how to evaluate their own practice and intervention techniques.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the 2020 median pay for social workers was $51,760 per year. The highest-paid 10% of social workers earned more than $85,820, while the lowest 10% earned less than $33,020. The annual mean wage of health care social workers was $57,630 in 2020, the BLS reports. This is the average geriatric social worker salary as well, since the BLS considers geriatric social workers as part of the health care social worker group.

Employment of social workers is projected to grow 12% from 2020 to 2030, much faster than the average for all occupations, according to the BLS. Increased demand for health care and social services will drive employment growth, but the prospects of each specialization, such as geriatric social workers, will vary.

Below are six common steps to become a geriatric social worker:

- Earn a bachelor’s in social work or in a related field.

- Pursue an MSW with relevant coursework.

- Seek an internship in an adult health care setting and complete the required fieldwork.

- Take the licensing exam.

- Earn relevant certifications.

- Apply for state social work licensure.

Sponsored Online MSW Program

Simmons University

Simmons school of social work (ssw).

Aspiring direct practitioners can earn their MSW online from Simmons University in as few as 9 months . GRE scores are not required, and the program offers full-time, part-time, accelerated, and advanced standing tracks.

- Prepares students to pursue licensure, including LCSW

- Full-time, part-time, and accelerated tracks

- Minimum completion time: 9 months

info SPONSORED

Due to the medical, social, emotional and mental health challenges that senior citizens face, those interested in entering the field of geriatric social work may need a master’s in social work degree from an institution accredited by the Council on Social Work Education , and to complete graduate-level field internships in settings that serve geriatric patients and older adults in need. Courses that may be helpful in this field include clinical social work modalities, family dynamics and social work in medical settings. Classes that focus on the physical, mental, emotional, financial and social issues associated with aging are also important. Students may wish to find MSW programs that provide a selection of gerontology-focused classes, or an academic concentration in gerontological social work.

“I highly recommend taking whatever gerontology-focused classes your program offers. A basic course in death and dying is a wonderful asset, even just for you personally,” noted Charis Stiles, MSW, who is a Friendship Line manager at the Institute on Aging (IoA) in San Francisco.

Even if a program does not have many gerontology-specific courses, thinking proactively about the therapeutic modalities and social work concepts that might be most useful in your work with geriatric clients, and taking courses that focus on these areas, may help you prepare.

“My favorite class in social work school was motivational interviewing, which is a technique of counseling where you use open-ended questions and don’t provide people with answers to their problems, but rather have them come up with the solutions themselves,” said Laura Burns, MSW, a medical social worker at On Lok Lifeways, a PACE program in San Jose, California. “In motivational Interviewing, the counselor mirrors the clients’ ideas back to them. This is a technique that I have used a lot in the hospital setting as well as my current job.”

Gaining experience working closely with geriatic clients and older adults through one’s graduate field placements and volunteer work and jobs is also an important part of preparing for a career in geriatric social work.

“I think some people really find it fascinating, and for others, it’s just not their cup of tea,” Burns said. “There are tons of ways to gain experience: reading books, watching movies, taking classes or training, and just talking with your own family. If you’re interested in geriatric social work, talk with your grandparents about their lives and their health problems.”

Burns also recommends students advocate for the types of field placements they want during their MSW program. “Field placement is a good way to get a variety of experience, but really if you know the type of work you want to do, be really, really clear about that during your program,” she said. “I knew that I wanted to work in health care, so I went and found internships in health care. I know some schools won’t let you do that, but thankfully, my school did.”

Stiles similarly advises social work students to gain relevant internship experiences during their graduate education, and to engage in extracurricular and volunteer work to interact with aging populations. “If you can find a placement with older adults, I highly recommend it. Adult day health care is a good first placement because you will get to interact with a large variety of older adults,” she said, adding, “Volunteering in settings like hospice, senior centers, or even the library may also be a good introduction to this population.”

Stiles and Burns also explained how the field of gerontological social work requires a degree of emotional preparation and skill in talking about weighty or disconcerting issues such as death and terminal illness.

“One aspect of geriatric social work that may be different than other kinds of social work is that death is a more constant presence in our participants’ lives,” Burns explained. “Everyone has a different level of comfort thinking and talking about death. Some of our participants think more about their deaths than others, yet we discuss it with all of them. We often begin these conversations by asking questions such as, ‘How do you want the end of your life to be?’ and ‘What would your goals be for the last weeks or last days here?’”

Stiles advised social work students to be self-aware and open to evaluating and changing their preconceived notions about older populations and geriatric care. “I recommend reflecting on your own attitudes toward older individuals and being honest with yourself about your assumptions about the later stages of life,” she said. “Many of us have some degree of internalized ageism even if we don’t recognize it, and this exploration will help us in any field we go into. As much as we don’t think about it, we are aging all the time.”

Those who enter geriatric social work need to know about the issues that aging populations encounter and have relevant experience working with aging populations. While working as a social worker for elderly patients, they will employ problem-solving skills, patience and compassion daily and contend with challenges such as the complexity and severity of the conditions, stubborn systemic barriers to care and family conflicts that can interfere with clients’ treatment. Despite these challenges, however, gerontological social workers experience the satisfaction of granting a voice to a marginalized population in need, and also enjoy deep and rewarding connections with clients who have led rich and intriguing lives, and who deeply appreciate the compassionate care that gerontological social workers provide.

Geriatric social workers support clients and their families through a combination of psychosocial assessments, care coordination, counseling and therapeutic work, crisis management and interventions, and discharge planning.

Psychosocial Assessments

Gerontological social workers conduct psychosocial assessments to determine their clients’ mental, emotional and social needs, and to understand how these needs connect with their physical health and medical conditions. Mental and physical health are closely linked, and by gaining a holistic picture of clients’ mental, emotional and social circumstances, social workers help clients’ medical care providers and their families better understand how to develop a care plan as comprehensive and compassionate as possible.

Psychosocial assessments gather information on a client’s:

- Mental and emotional health, including past and present psychological conditions.

- Behavioral health challenges.

- Social, financial, familial, educational and occupational history and current situation.

- Medical and mental health treatment history.

- Current medications and adherence to treatment plans.

Gerontological social workers complete psychosocial assessments at the time of a client’s admission into a given care program (this type of psychosocial assessment is called an intake assessment), and also conduct regular assessments throughout a client’s time in the program.

Burns explained to OnlineMSWPrograms.com how social workers evaluate multiple facets of clients’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral health. “The social workers’ intake of a candidate is focused on the person as a whole and explores their support systems, psychosocial risks, cognition and mood,” Burns said. “The three main things that we assess for are changes in mood, behavior and cognition. We test for changes in cognition and mood every six months.”

Burns also noted that interacting closely with clients and connecting with them regularly allows her to evaluate their emotional and cognitive health at any point, and to convey any concerning changes to the treatment team. “[E]ach time I’m checking in on someone, even if it seems just like a social visit, I’m also checking in on their emotional well-being,” she said. “As social workers, we don’t just do formal screenings; we also do informal check-ins with the participants all the time. Also, we don’t have to wait until a participant is due for a formal assessment to make an adjustment in their care plan; we are able to modify it at any time.”

In addition to being essential for the development and improvement of a client’s care plan, psychosocial assessments help social workers determine whether a client is at risk of experiencing adverse mental, physical, and/or behavioral health outcomes—for example, if a client shows signs of depression, has suicidal tendencies, or is neglecting his or her medication. These evaluations of risk to clients, also known as risk assessments, help social workers and other members of a client’s care team determine the appropriate courses of action to address factors that may seriously compromise a client’s well-being.

Care Coordination

Another responsibility that gerontological social workers have is care coordination, which is the purposeful organization of different teams and services to effectively address a client’s overall health care needs (physical, cognitive, emotional, and social). Care coordination involves completing psychosocial assessments to inform the larger treatment team of a client’s needs. It also means participating in or facilitating meetings between different providers to discuss patient treatment and health outcomes; conveying the concerns and desires of the patient and his or her family to the teams involved in their care; and connecting clients and their caretakers with resources within the larger community that may provide additional support.

Counseling and Therapy

Gerontological social workers provide counseling and therapy to clients to help them cope with the psychological, emotional, social and financial challenges that come with aging. They also provide therapy and advise clients’ families and loved ones as necessary. During sessions with clients, social workers may employ a variety of psychotherapeutic techniques to help them manage negative emotions, set objectives for life improvement, address behavioral problems or psychological barriers to meeting certain goals, and (where applicable) make end-of-life preparations.

When working with the families of their clients, gerontological social workers may help them manage the difficulties they may encounter caring for an aging loved one, including strains on financial resources and relationships, and processing grief and other emotions around loss.

Specific therapeutic techniques gerontological social workers may use in their work with clients and families may include cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, motivational interviewing and mindfulness-based stress reduction. For more information about these and other therapeutic modalities social workers may use when providing clinical therapy to clients, see our Guide to Clinical Social Work or check out the National Association of Social Workers website .

Crisis Management and Interventions

Depending on their role and work setting, gerontological social workers may encounter a variety of client crises. Some clients may struggle with depression, suicidal desires, acute dementia that renders them unable to care for themselves, family conflicts about treatment decisions, traumatic experiences that require immediate support, or mental or emotional disorders that pose a danger to themselves or others. Clients may also be the victims of neglect, domestic abuse, exploitation and other crimes.

In these instances, gerontological social workers may have to intervene with a number of measures to ensure client safety and well-being. These may include providing emotional support and counseling to clients and their family members; managing difficult conversations among client, family and care providers; contacting relevant organizations and/or authorities in the case of elder abuse; and developing a short- and long-term support plan for clients and their loved ones.

Burns explained some of the crisis intervention services she provides at On Lok Lifeways. “Since we screen for changes in mood, if someone is doing fine emotionally and then all of a sudden they’re severely depressed or suicidal or homicidal, that’s obviously something to communicate immediately to the medical team and the participant’s family,” she said. “We consult with Adult Protective Services to report cases of abuse or neglect. We let their doctor know to see if they need to have a medication adjustment, and we’ll usually also recommend meetings with the chaplain or the mental health counselor who works on site as well.”

Gerontological social workers may also provide crisis support and interventions in non-medical settings. Stiles also helps the older adults during crisis situations by coordinating volunteer services for the IoA’s suicide prevention and grief support hotline.

“The Friendship Line at the Institute on Aging provides suicide prevention and trauma grief support to older adults and adults with disabilities. It’s a 24-hour hotline that operates from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. in the office and after hours remotely,” she said “Callers are primarily over the age of 60 and are dealing with isolation, loneliness, depression, grief and illness. Many have mental health conditions, some treated and some untreated, and many also have a history of trauma. We have between 50-70 volunteers who are the primary hotline counselors.”

Resource Navigation and Benefits Application Guidance

Gerontological social workers also help clients and their families understand and apply for health care benefits and other financial or social assistance at the federal, state and local community levels. Clients and their loved ones may have a hard time navigating health insurance benefits, social security, and making use of community support systems. Social workers may guide clients through these steps and connect them with local support systems, such as senior centers, discounted or pro bono counseling, free community clinics, and subsidized food and housing if necessary.

Discharge Services

Consistent with their role as care coordinators, gerontological social workers often develop and coordinate a discharge plan for clients when the time comes for them to transition from one care setting to another—for example, from inpatient to outpatient care, or from residential care to home care. When coordinating a client’s discharge from a care setting, social workers typically contact the relevant parties involved in the transition and organize logistics such as transportation, health insurance and medical financial aid, and paperwork and documentation. They may also consult with the client and his or her family to prepare them for the change.

Geriatric social workers work with older populations in many settings. At any organization that serves the physical, mental, emotional and social needs of senior citizens, geriatric social workers may play a crucial role providing direct care (counseling and advising, resource navigation services, etc.), as well as care coordination (contacting different departments, care providers, and organizations to ensure clients get the inpatient or outpatient support they require). Common work environments that employ gerontological social workers include medical settings, adult health programs, programs for all-inclusive care for the, hospices, nursing homes and residential care facilities.

Hospitals and Medical Centers

Hospitals and medical centers typically have inpatient and outpatient divisions to support older patients who suffer from chronic or acute health conditions. For example, hospitals may have geriatric acute and emergency care units, fracture care centers, palliative care, and a geriatric oncology unit. Gerontological social workers may work in the geriatric departments of hospitals and medical centers as part of a specific unit or across multiple units.

Gerontological social workers who work at hospitals and medical centers collaborate with a larger medical team of physicians, nurses, medical assistants, psychologists and other staff. They evaluate patients’ needs, develop a treatment plan, coordinate geriatric patients’ care, and maintain and submit patient records and documentation. They also counsel patients and their families and help them navigate resources.

Some medical centers also have adult day health programs that provide daily activities, counseling and social support services to patients so they may remain at home instead of transitioning to a nursing home. Social workers in these settings may coordinate activities, programs and other services for their clients, provide counseling services and connect clients and their families to resources within or outside the program.

Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) provide comprehensive medical, mental health and behavioral health care to people who are eligible for Medicaid or Medicare. These programs employ an interdisciplinary team of medical, mental health, behavioral and social service specialists who provide patients with care in their homes and/or at day treatment centers.

“We have a day health center where participants come to receive different types of activities, socialization and cognitive stimulation including pet therapy and bingo,” Burns said about On Lok Lifeways. “There’s also a clinic on site with three doctors and one nurse practitioner and several nurses. All of our participants are given a full physical exam before they are enrolled and they are evaluated every six months, or as health conditions occur. We also have a rehab team, which includes occupational therapists and physical therapists. We have a home care team of nurses and aides who provide people with showers, assist them with meals, provide medication reminders, and help them with chores and laundry in their home.”

Burns said social workers are an important part of PACE programs’ interdisciplinary team, serving as patient advocates and as the bridge of communication between patients and caregivers, and between different health providers and teams.

“Social workers are connected to all of the aforementioned teams. It is our job to connect our patients with the services that these teams provide, and to connect the teams with one another as necessary to ensure proper emotional, mental and physical care for our participants,” she said. “We also are the primary point of contact for our participants’ family members. Social workers at On Lok also play an important role in the initial assessment of patients, and in the development of their care plan.”

Social workers who work at PACE programs typically have similar work settings and responsibilities as social workers who work in geriatric departments of hospitals and medical centers. However, PACE programs provide more comprehensive services, combining medical, mental and behavioral health care, and serve clients who are eligible for Medicare or Medicaid. Therefore, social workers at such programs may connect with more organizations, provide a wider range of care coordination services and travel across different settings. For example, they may also conduct home visits, help patients and their families navigate the process of applying for medical benefits, and communicate with medical, mental health and behavioral, and social services departments within their program.

Specialized Senior Assistance Programs

Gerontological social workers may work for specialized programs that support senior citizens in a certain area of their life, such as financial literacy, community engagement, housing coordination and low-income support services. For example, social workers may work for a community service organization that serves low-income older adults and helps them find stable housing, health care or disability assistance, or they might work for an organization that provides financial advice, subsidized nutrition programs or home care services.

Some larger organizations, such as San Francisco’s Institute on Aging , fund a wide range of programs and conduct research on how society and local, state and federal governments may better support older populations. Social workers may work for these larger organizations, within one or more programs.

Hospices provide palliative and end-of-life care to people suffering from terminal illnesses or conditions. Gerontological social workers in hospice settings work with patients and their families, providing emotional support, grief and bereavement counseling, resource navigation and care coordination. Hospices typically provide patients with symptom and pain management (palliative care) and assistance in end-of-life planning. Hospice social workers engage in all the non-medical aspects of a patient’s care, including coordinating community resources, answering patients’ and family members’ questions, helping family members cope with the loss of a loved one, and assisting clients in managing their family and social relationships during their time in hospice care.

Nursing Homes and Residential Care Facilities

Nursing homes provide residential support to people who cannot live independently due to mental or physical conditions such as dementia or disability. The transition to a nursing home or a residential care facility may be psychologically, emotionally and financially challenging. Gerontological social workers in these settings help clients and their families during this transition and ensure they receive the services they require both during their admission and throughout their stay. They may also help develop and review nursing home policies and procedures to ensure that residents receive the care and attention they need.

Gerontological social work provides the opportunity to connect deeply with those in need who are often appreciative of the support, and who have a wealth of life experiences and perspectives to share. Serving as an advocate for clients who would not otherwise have a voice in their care may also be gratifying and empowering. In addition, this field of social work involves working with clients’ families and loved ones, which may form unique and rewarding connections.

“One of the most rewarding experiences are the long-term relationships I have with my participants and knowing that I am able to make a difference in their lives,” Burns said. “I find it very rewarding to build relationships with my participants and know that part of my treatment plan is to check in with them. I feel really blessed that I get paid to do this work, to connect and learn about people who have lived very interesting lives—very different, often, from the life that I have led.”

She also noted how her role as a geriatric social worker enables her to share more about herself with her patients, relative to other types of medical settings, which at times allows for deeper and more rewarding connections.

“I think one thing that I’ve noticed in geriatric social work is because I have such long-term relationships with people, I’m able to share a little bit more of myself,” she explained, “In hospitals you’re working with someone for a short amount of time, and you just need to focus on them, and they don’t get as much of an opportunity to also learn a little about you.”

In addition to her work at the Institute on Aging, Stiles worked as a medical social worker, bereavement coordinator, and bereavement and volunteer manager at Odyssey Healthcare, a hospice setting in which she served geriatric patients and their families. She said it has been very fulfilling to have a positive impact on patients’ well-being and relationships, and helping them preserve their comfort and dignity as they manage difficult health conditions.

“I have had so many rewarding experiences with clients—so many frail, dying individuals I’ve had the honor of working with and being present for, so many people I’ve been privileged to advocate for when they were not able to speak for themselves, so many grieving families I’ve been able to comfort and counsel,” she said. “It’s been really incredible how many clients have really touched me.”

Some of the primary challenges of gerontological social work include the complexity and severity of some clients’ challenges (which at times necessitate difficult conversations about end-of-life care and planning), instances of elder abuse or neglect, age-based discrimination, family conflicts that interfere with appropriate or sufficient care, and the challenges and limitations within the health care system that may prevent older patients from receiving the medical attention and resources they need.

Stiles said older clients can often face a combination of challenges, including prejudice against people who are aging, senior citizens’ changing occupational and/or financial status, and the physical and mental declines that tend to come with aging.

“Older adults face many of the same concerns and issues as any adult-limited resources, mental health issues, substance abuse, history of trauma, systemic racism, homophobia, classism, etc.,” she said. “What makes older adults ‘unique’ is that they are dealing with these concerns with the added pressure of ageism (discrimination against people based on their age) and ableism (discrimination against those with disabilities), as well as potential physical health changes and accumulated losses.”

Managing family members’ concerns—or their lack of concern—can also prove challenging. “While many families are wonderful to work with, other families are very difficult to work with,” Burns noted. “Families often are at one end or the other of the spectrum, very, very involved and high maintenance, and then there are other families that you call and call and cannot get them to call you back. It is important to have strong relationships and build trust with all families that you work with.”

Encountering systemic injustices that particularly hurt elders can also be a challenge that gerontological social workers encounter on the job. “Many of the challenges I’ve faced with clients are primarily due to longstanding, often untreated mental illness that clients have been dealing with for decades,” Stiles noted. “Often, there are systematic issues like generational poverty, lack of services in the community and a general lack of concern for older adults unless in a medicalized setting.”

To manage the challenges of the work, social workers suggested that students manage their expectations about what they are able to do to help clients, and appreciate their successes while learning from their mistakes.

“For new social workers, I recommend keeping perspective and understanding the limitations placed on people in this profession,” Stiles said. “Many issues an older client is dealing with are issues they’ve been dealing with for decades. We cannot solve family discord, we cannot solve poverty, we cannot solve regrets or mental illness or a lack of services. This is incredibly difficult and takes years of practice and self-reflection.”

Burns said she remains optimistic and turns the challenges she encounters into opportunities to connect with her clients and their families, and to better meet their needs and concerns. “It’s very rewarding when you are able to build trust with a family that is hard to reach or get them to agree to provide care that they have been resistant to provide,” she noted.

Find out how to become an LCSW today.

When should a geriatric social worker be consulted?

A geriatric social worker may be brought into a case if a patient has physical or emotional needs, conflicts or resistance, or unresolved safety concerns. Geratric social workers may also assist with discharge and follow-up after a hospital visit. They may even help make sure the details of patients’ end-of-life decisions are in order.

Why are geriatric social workers needed?

Geriatric social workers are a patient’s advocate and may help them receive the care they need. They distinguish between normal and abnormal aging and help connect clients to community resources available in the area. For example, a geriatric social worker refers older adults for home care services if safety oversight or assistance with personal care is needed.

How much do gerontology social workers make?

The median annual wage of social workers was $51,760 in 2020, the BLS reports. The BLS categorizes social workers who specialize in a geriatric setting as health care social workers. So, to find the average geriatric social worker salary, analyze BLS data for health care social workers. According to BLS data, the 2020 mean wage of health care social workers was $57,630.

What type of social worker gets paid the most?

According to 2020 annual mean wage data for social workers from the BLS , “social workers, all other” earn the most, an average of $63,670. Gerontological social workers may fit within healthcare social workers, who earn a median annual wage of $54,310. Here are the mean wages of other types of social workers, as reported by the BLS:

- Child, family and school social workers: $51,650

- Mental health and substance abuse social workers: $48,570

What is the difference between a geriatric social worker and other social workers?

All social workers are committed to the well-being of individuals, families and groups. Geriatric social workers focus on the health of older patients and those who are most vulnerable. They are specially trained in the issues commonly facing older people, including anxiety, dementia, depression, financial instability, isolation, and other emotional and social challenges. They are also trained in providing clients with access to other care and support programs they need.

Last updated: February 2022

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A Role for Social Workers in Improving Care Setting Transitions: A Case Study

Ruth d. barber.

Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

ALEXIS COULOURIDES KOGAN

Anne riffenburgh.

Huntington Memorial Hospital, Pasadena, California, USA

SUSAN ENGUIDANOS

High 30-day readmission rates are a major burden to the American medical system. Much attention is on transitional care to decrease financial costs and improve patient outcomes. Social workers may be uniquely qualified to improve care transitions and have not previously been used in this role. We present a case study of an older, dually eligible Latina woman who received a social work–driven transition intervention that included in-home and telephone contacts. The patient was not readmitted during the six-month study period, mitigated her high pain levels, and engaged in social outings once again. These findings suggest the value of a social worker in a transitional care role.

INTRODUCTION

High rates of readmissions among American hospitals have an enormous impact on quality of life and costs of care of the American health care system ( Bjorvatn, 2013 ; Coleman, Parry, Chalmers, & Min, 2006 ; Hansen, Young, Hinami, Leung, & Williams, 2011 ; Hernandez et al., 2010 ; Williams, 2013 ). Thirty-day readmission rates are an accepted marker of discharge success and a reflection of quality of care ( Allaudeen, Vidyarthi, Maselli, & Auerbach, 2011 ; Bjorvatn, 2013 ; Jha, Orav, & Epstein, 2009 ; Vashi et al., 2013 ). It appears that American hospitals are not performing as well as desired: it is estimated that 20–25% of Medicare beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge and that these readmissions cost $26 billion annually ( Allaudeen, Schnipper, Oray, Wachter, & Vidyarthi, 2011 ; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2012 ; Graham, Leff, & Arbaje, 2013 ; Hansen et al., 2011 ; Hernandez et al., 2010 ; Jencks, Williams, & Coleman, 2009 ; Voss et al., 2011 ). This amount accounts for 17–24% of overall Medicare hospital expenditures, ( Jencks et al., 2009 ), which is especially concerning considering that 75% of readmissions are thought to be avoidable ( Hansen et al., 2011 ).

Poor transitions that lack care continuity have been found to lead to adverse outcomes and greater risk of readmission, especially for older adults ( Arbaje et al., 2008 ; Coleman, Parry, Chalmers, & Min, 2006 ; Jencks et al., 2009 ). In fact, the Institute of Medicine has explicitly identified transitional care as a high-priority area for performance measurement ( Institute of Medicine Staff, 2006 ). Recent studies have found that lack of primary care follow-up within seven days of discharge increases risk of 30-day readmission tenfold ( Hernandez et al., 2010 ; Takahashi et al., 2013 ). Other issues at discharge include lack of communication with the primary care physician (PCP) at discharge, a decreasing number of available PCPs ( Williams, 2013 ), inadequate or nonexistent medication reconciliation ( Boling, 2009 ), incomplete or inaccurate information transfer to the next provider ( Boling, 2009 ; Williams, 2013 ), and patient non-compliance with prescribed medications ( Boling, 2009 ). These issues can lead to inadequate patient and caregiver preparation for quality care at the next health location ( Coleman et al., 2004 ; Coleman, Parry, Chalmers, Chugh, & Mahoney, 2007 ) lack of preparation for self-management role, lack of access to a health care practitioner to address direct concerns, and minimal input in patient care plans ( Institute of Medicine Staff, 2006 ). Additionally, multiple transitions that lead to readmissions are common. It is estimated that over 30% of patients undergo more than one post-hospital transfer after discharge ( Coleman, Min, Chomiak, & Kramer, 2004 ) and one out of seven patients discharged from hospitals have four to six transitions within three months, increasing the potential for mismanagement ( Boling, 2009 ; Coleman et al. 2006 ; Hernandez et al., 2010 ; Kocher & Adashi, 2011 ). These shortcomings ultimately lead to greater use of hospital and emergency services ( Coleman et al. 2004 , 2006 ). As a result, national attention has been given to streamlining and improving care coordination during the discharge process to reduce avoidable readmissions, especially since the mere documentation of providing discharge instructions to patients has failed to significantly reduce readmission ( Allaudeen et al., 2011 ; Hernandez et al., 2010 ; Jha et al., 2009 ).

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) ( Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010 ), the fee-for-service system provided hospitals incentive for a short hospital stay, without penalty for unfavorable outcomes, such as high readmission or mortality rates ( Bueno et al., 2010 ; Johnson & McCarthy, 2013 ; Kamerow, 2013 ). For common diseases like chronic heart failure, readmission rates increased, yet mean length of stay in hospital decreased by 26% ( Bjorvatn, 2013 ; Bueno et al., 2010 ). Discharge disposition also changed significantly in recent years, with a 53% relative increase in proportion of discharges to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and a 10% reduction in discharges to home ( Bueno et al., 2010 ). Among those discharged to home, greater percentages of patients are unstable, making post-discharge home care an important target for improvement ( Kosecoff et al., 1990 ).

Now, due to the ACA, incentives for reducing readmission have changed. Hospitals are being penalized for excessive readmissions, defined as the ratio of a hospital’s readmission performance compared with the national average for the set of patients with an applicable condition, among other criteria ( Allaudeen et al., 2011 ; Fontanarosa & McNutt, 2013 ; Lacker, 2011 ). Penalties for readmissions are currently incurred among patients diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia, with more conditions to be added in 2015 ( Kocher & Adashi, 2011 ). Penalties currently entail a 2% reduction in Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System reimbursements for all expenses during readmissions for pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure. This figure will increase to 3% in 2015 and is expected to also include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous coronary interventions, and other vascular procedures. These penalties cost hospitals—and save Medicare—an estimated $300 million per year ( Fontanarosa & McNutt, 2013 ; Jencks et al., 2009 ; Kamerow, 2013 ).

The need to reduce hospital readmission among older adults has never been more pressing. The national population of adults over 65 years old is projected to rise from 14% to 20% by 2030, and then peak at 25% by 2050. Additionally, adults over 85 are expected to increase by 400% by 2050, and their cost of care has been found to be eight times that of the average adult ( Allaudeen et al., 2011 ; Bjorvatn, 2013 ; Hackstaff, 2009 ). This puts quite a burden on an already indebted health care system, which is projected to cost 30% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2035 and 50% by 2085 ( Hackstaff, 2009 ). In addition to reduced health care costs, improved transitions from hospital to home will result in better quality of life for patients and better health outcomes for the general public ( Allaudeen et al., 2011 ). Low-cost interventions focused on education, medication management, and peer support have demonstrated reductions in 30-day hospitalizations ( Boling, 2009 ; Brock et al., 2013 ; Coleman et al., 2004 ; Jack et al., 2009 ). Interventions, especially those that utilize “transition coaches” that guide patients toward activation and self-care, have a significant association to reductions in rehospitalizations and emergency department visits for at least six months following discharge ( Brock et al., 2013 ; Coleman et al., 2004 ; Dharmarajan et al., 2013 ; Johnson & McCarthy, 2013 ; McCarthy et al., 2013 ) A recent review of 14 hospital-to-home transition interventions showed a mean reduction of 5.7% in rehospitalizations ( Brock et al., 2013 ). Interdisciplinary interventions have also resulted in fewer emergency departments visits and better health outcomes ( Brock et al., 2013 ; Johnson & McCarthy, 2013 ). Interventions that provide home-visits also have shown significant positive effects on mortality, admission, readmission, and nursing home placements ( Elkan et al., 2001 ). Discharge planners and home health services that focus on the home transition are now positioned to play a more active role in care transitions, due to their simplicity and relatively low cost of implementation ( Coleman et al., 2004 ).