Should cell phones be banned from all California schools?

New school year brings new education laws

How courts can help, not punish parents of habitually absent students

How earning a college degree put four California men on a path from prison to new lives | Documentary

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

Getting Students Back to School

Calling the cops: Policing in California schools

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in Higher Education: California and Beyond

Superintendents: Well paid and walking away

Keeping California public university options open

August 28, 2024

Getting students back to school: Addressing chronic absenteeism

July 25, 2024

Adult education: Overlooked and underfunded

Career Preparation

Teachers say critical thinking key to college and career readiness

Louis Freedberg

September 29, 2015.

California teachers say critical thinking skills, not scores on standardized tests, are the best way to assess whether students are prepared for success in college and the workplace, according to an online survey by EdSource in partnership with the California Teachers Association.

Teachers said they have received much more training on how to prepare students for college – and far less on preparing them for non-college options.

They also said college and career readiness has not been fully integrated into the professional development training they have received to implement the Common Core State Standards.

Preparing students to graduate from high school prepared for college and careers is now a principal goal of all major education reforms being implemented in California, including the Common Core standards and the Local Control Funding Formula, which was approved by the state Legislature in June 2013. This represents a major shift from the goal of the No Child Left Behind reforms of the past 15 years, which was to promote proficiency on standardized tests.

The survey of 1,000 teachers randomly selected from among a list of CTA’s more than 300,000 members was conducted last spring. Carried out by the polling firm GBA Strategies, it is the first of its kind to probe teacher attitudes regarding college and career readiness. The survey was partially underwritten by The James Irvine Foundation.

Defining what exactly “college and career readiness” means – and what it will take to ensure that students reach that goal by the time they graduate from high school – is currently a major concern of educators and policy makers around the state, and the teachers’ role in making that happen will be critical.

Teachers overwhelmingly supported the goal of preparing students for college and careers. When asked to rank the most important indicators of college and career readiness, 78 percent of teachers ranked developing critical thinking skills among the three most important indicators. Eight percent of teachers ranked proficiency on the Smarter Balanced test, which more than 3 million students took for the first time last spring, among the three most important indicators.

“I think most college professors would agree that students’ ability to think critically and analyze texts, and to integrate information is much more important than what they did on a test,” said David Plank, executive director of Policy Analysis for California Education, or PACE, a joint policy and research institute of UC Berkeley, Stanford University and the University of Southern California. “The disagreement would come from admissions officers who find tests very efficient in deciding who is eligible for admission or not.”

David Conley, professor of education policy at the University of Oregon, and president of EdImagine, a strategic consulting firm that is working on college and career readiness issues with school districts in California and the California Department of Education, welcomed teachers’ emphasis on critical thinking skills, but he said that the high school curriculum has largely not reflected that emphasis. “The arrows are all pointing toward greater alignment of high school and college, but the challenge will be course redesign at the high school level in particular, and training (of teachers) in new instructional methods,” he said.

Just under one third (30 percent) of teachers said their districts have clearly defined standards for what constitutes college and career readiness. Thirty-five percent say that their districts have standards, but that they are not clearly defined. Eight percent say their districts have no standards at all.

Conley, who authored “ Getting Ready for College, Careers and the Common Core ,” said that it is essential that districts adopt a specific definition of college and career readiness that goes beyond just requiring students to meet the A-G course requirements for admission to UC and CSU. He said what will be needed “is a definition that you can put into operation through professional development (of teachers) and curriculum development. A vague definition doesn’t do you any good.”

At a time when teachers are being asked to take on a number of new reforms, nearly three-fourths of teachers say they are either “very satisfied” or “fairly satisfied” with their jobs. Thirty-one percent of teachers support the Common Core standards, and nearly half support the standards with some reservations. Twelve percent say they are opposed to the standards altogether.

The survey also provides some guideposts for what additional resources teachers feel they need to adequately prepare students for college and careers. At the top of their list are programs that link the high school curriculum to the workplace with a specific career pathway along with more high school career-technical courses.

“High schools have historically done a better job preparing students to graduate ready for college,” said Jon Snyder, executive director of the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. “They have not done as good a job in our schools preparing students for careers.”

Snyder said it was important to “break down the false dichotomy between college and career.” “We used to say college or career, and you had these two tracks,” he said. “It is important to say ‘both and,’ not ‘either or.'”

Key Findings Include:

Support for college and career readiness as a goal

- More than three-fourths of teachers say they believe that preparing students to be ready for college and the workplace by the time they graduate from high school is a very or somewhat realistic goal. Twenty-three percent feel it is not very realistic or not realistic at all.

- There are differences in teacher attitudes depending on the socioeconomic backgrounds of the students in the schools where they teach. About 58 percent of teachers in schools where fewer than 1 in 4 of their students are eligible for free or reduced-priced meals believe that college and career readiness is a “very realistic” goal. But 20 percent of teachers in schools where more than 3 in 4 students qualify for federally subsidized meals have similar attitudes.

Lack of clearly defined standards

- Thirty percent of teachers say their districts have clearly defined standards for what constitutes college and career readiness. Thirty-five percent say that their districts have standards, but that they are not clearly defined. Eight percent say their districts have no standards at all.

Little professional development or training for non-college options

- Although almost all teachers consider themselves knowledgeable about what should be done to prepare students for college and careers, 36 percent say they have received specific training to help them prepare students for college over the past two years.

- Eight percent say they have received training to prepare students for options other than college.

- At the high school level, 43 percent of teachers say they have received training to prepare students for college, and 14 percent say they have received training for other career options.

- Those teachers who have received training say that the professional development training they have received in preparing students for college and careers has been useful to them (69 percent).

College and career readiness training often not integrated with Common Core training

- Seventy-nine percent express support for the Common Core standards (31 percent support them unconditionally, while another 48 percent support them “with reservations”). Twelve percent are unequivocally opposed to them.

- At the same time, the majority of teachers (51 percent) say that the goal of college and career readiness has not been integrated into the workshops, in-service training or professional development related to the Common Core they had participated in. Ten percent said that college and career readiness was “very strongly integrated” into this professional development and training.

Resources teachers need

- Teachers ranked career academies, linked learning or other programs that tie the high school curriculum with a specific career pathway as the No. 1 resource their school or district needed most to prepare students for college and careers.

- Ranked second and third respectively are more high school career-technical courses and additional school counselors to help students make choices about colleges or alternatives to college.

- Teachers who were aware of programs outside of their school district to promote college and career readiness also placed a very high value on workplace internships – with nearly two-thirds listing internships as an effective way to prepare students for college and careers.

Survey Documents

Share Article

Comments (8)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Peg Maddocks 9 years ago 9 years ago

It's refreshing that a majority of teachers are clear and in agreement on what the most important skills are for students to be successful in the real world. Providing internships, mentors, authentic projects, and community resources enriches students' capacity to be ready and to launch themselves, whether they go to college or careers or both. Critical thinking in the classroom means letting kids be at the center with the responsibility and freedom to analyze problems, … Read More

It’s refreshing that a majority of teachers are clear and in agreement on what the most important skills are for students to be successful in the real world. Providing internships, mentors, authentic projects, and community resources enriches students’ capacity to be ready and to launch themselves, whether they go to college or careers or both. Critical thinking in the classroom means letting kids be at the center with the responsibility and freedom to analyze problems, collaborate on ideas, and communicate unique solutions. I hope the CCSS is eventually seen as one way to measure these abilities.

Jim 9 years ago 9 years ago

The idea that everybody has the cognitive level needed to complete college is simply nuts. Most people with IQ’s above 110 could probably get through college and perhaps it might be possible for individuals with IQ’s of say 105. But the idea that someone with an IQ of say 90 could do college level work is beyond crazy. About 25% of the US population has an IQ below 90.

Ellen Moir 9 years ago 9 years ago

Most teachers seem excited about the possibilities new standards represent, and hopeful they will receive the professional learning and support they need to make sure their students are successful. The challenge ahead is to build a profession of teachers who are trusted; who are constantly learning; who know they can take risks to reach every student; who persevere in solving complex issues; who are open to feedback that helps them grow professionally; and, ultimately, who … Read More

Most teachers seem excited about the possibilities new standards represent, and hopeful they will receive the professional learning and support they need to make sure their students are successful. The challenge ahead is to build a profession of teachers who are trusted; who are constantly learning; who know they can take risks to reach every student; who persevere in solving complex issues; who are open to feedback that helps them grow professionally; and, ultimately, who believe all students can learn and meet higher standards.

We can get there by giving teachers on-the-job coaching that meets their specific needs while helping them make a difference for students.

zane de arakal 9 years ago 9 years ago

Dropping the term Vocational Educational affected current curricular planning.

Gary Ravani 9 years ago 9 years ago

This survey's results align nicely with my experience over the course of several years in discussing CCSS with teachers from up and down the state. That puts about 8 in 10 in support, to varying degrees of the CCSS, and 2 in 10 adamantly against. As is typically the case in controversial issues the "against" folks are really, really adamant while the pro folks are much more moderate in their support. This also points out … Read More

This survey’s results align nicely with my experience over the course of several years in discussing CCSS with teachers from up and down the state. That puts about 8 in 10 in support, to varying degrees of the CCSS, and 2 in 10 adamantly against. As is typically the case in controversial issues the “against” folks are really, really adamant while the pro folks are much more moderate in their support.

This also points out that implementation of CCSS, as well as SBAC, is a complex, time driven, resources driven project. Time is scarce in the schools with US teachers having little time to collaborate compared to international peers, and teachers in CA are particularly burdened by high number of students in classrooms and a lack of resources. The latter issues are both inextricably linked to CA’s poor fiscal support for the schools.

CA is currently blessed with policy leadership, both at CDE and the SBE, who understand the level of difficulty schools will have in implementing CCSS and are attempting to mitigate the situation by building some flexibility into the time component of the process. For this they receive a lot of criticism from those who understand the difficulties facing the schools, but want to use the difficulties as levers to drive an anti-public school, anti-teacher agenda. Policy leadership often seem reluctant to address the resources component likely to avoid getting on the wrong side of the notoriously “frugal” governor.

Joy Dugan 9 years ago 9 years ago

The skills mentioned int he article are essential. I work as an educator in a vocational field, Consumer & Family Sciences, and developed and taught at the Middle School & High School level coursework exploring careers and career clusters. This type of course has been helpful to students as it brings more relevance to their coursework. It also assists them in choosing outside of class activities to gain experience.

Jason May 9 years ago 9 years ago

I don't see any indication that this survey ever defined what "critical thinking skills" means. So a bunch of teachers said that an undefined and unmeasurable factor might be more important than "hard" test scores? That's not surprising at all. Standardized test scores are clearly not the best way to assess much of anything. But I've heard no clear proposal for an alternative, and this survey doesn't offer anything new. Read More

I don’t see any indication that this survey ever defined what “critical thinking skills” means. So a bunch of teachers said that an undefined and unmeasurable factor might be more important than “hard” test scores? That’s not surprising at all.

Standardized test scores are clearly not the best way to assess much of anything. But I’ve heard no clear proposal for an alternative, and this survey doesn’t offer anything new.

There is a considerable body of professional literature on the skills in the category of “critical thinking.” It is far too extensive to be covered here. You will need to do some research and a lot of reading.

EdSource Special Reports

Communication with parents is key to addressing chronic absenteeism, panel says

Low-cost, scalable engagement through texting and post cards can make a huge difference in getting students back in the habit of attending classes.

Helping students with mental health struggles may help them return to school

In California, 1 in 4 students are chronically absent putting them academically behind. A new USC study finds links between absenteeism and mental health struggles.

Millions of kids are still skipping school. Could the answer be recess — and a little cash?

Data gathered from over 40 states shows absenteeism improved slightly but remains above pre-pandemic levels. School leaders are trying various strategies to get students back to school.

California districts try many options before charging parents for student truancy

A 2010 law sponsored by then-District Attorney Kamala Harris, allows for the arrest of parents of chronically absent students.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

College Readiness Consortium

- What Schools Need to Know and Do

- What Students Need to Know and Do

- Ramp-Up to Readiness Website

- Policy and Youth Program/Event Registration

- Find a UMN Youth Program

- Training/Events

- Middle School Visits

While preparing all students for postsecondary success is a relatively new challenge, a growing body of research shows us what students need to do to be prepared. It is summarized in a simple acronym: RAMP, or Rigor-Access-Motivation-Persistence .

- Rigor: preparation to handle higher expectations, faster pacing and deeper thinking skills

- Access: providing students and families information on key components of college admissions and finances

- Motivation: a vision of a student’s future that supports engagement in school

- Persistence: helping students stick to their education in the face of challenges

College readiness means preparation to handle the higher expectations, faster pacing and deeper thinking skills needed in college courses. Research conducted by Dr. David Conley of the University of Oregon digs into the necessary content knowledge beyond course names and identifies “writing skills, algebraic concepts, key foundational content and ‘big ideas’ from core subjects” as essential knowledge needed for postsecondary success, along with key cognitive strategies: analytic reasoning, problem solving, inquisitiveness, precision, interpretation and evaluating claims.

Surveys consistently show that many students, and their parents, do not know what college admission requirements involve, what kind of financial aid is available, and that community and technical colleges often have academic placement requirements. Students and their families need ‘college knowledge’, which is formal and informal knowledge about the different types of colleges, the admissions process, academic and testing requirements, tuition, placement and levels of challenge. Financial knowledge is critical as well, including basic budgeting, the risks of debt, and the value of some debt such as a reasonable amount of student loans.

Every student needs a vision of his or her future that can motivate hard work in school. A motivated student often develops a personal sense of direction and purpose, and channels the motivation towards a particular outcome. Career exploration helps students develop visions of their futures, and with guidance they can backwards map those potential future careers to the postsecondary education needed to succeed in them and the high school preparation needed to enter those colleges. This builds engagement in current learning, as they understand the connection with their future dreams. When students recognize why they should aim for success in school, understand the relevance of their academic classes, and know that they will benefit from their effort, they will be motivated to achieve college readiness.

Persistence

We know that getting to college – especially for a student who will be a first generation college student– takes incredible persistence. When students believe they are able to shape desired outcomes and develop social emotional skills to support success, they are more focused on tasks, cope better in the face of challenge and are likely to persevere after experiencing a setback or failure. For example, mindset greatly influences academic success. Students (and their teachers) who have a fixed mindset believe their abilities are set in stone, while those with a growth mindset believe they can improve their knowledge and skills with effort. Research demonstrates that students with a growth mindset show improvement in academic outcomes, while those with a fixed mindset did not.

- Our Mission

Resources and Downloads to Support College Readiness

Discover resources and information — including downloads from schools — related to developing the awareness, knowledge, skills, and attitudes that will prepare students to enroll and succeed in college.

Preparing Students Socially and Emotionally

- When Social and Emotional Learning Is Key to College Success : Read about the difference between college-eligible and college-ready and the social-emotional skills that can help kids find college success. ( The Atlantic , 2016)

- Failure Is Essential to Learning : Understand how helping students to reframe failure as part of the learning process can help them succeed in college and beyond. (Edutopia, 2015)

- Nurturing Intrinsic Motivation and Growth Mindset in Writing : Discover how one teacher’s strategies for preparing her students to read and write in college changed as she explored new ideas about student motivation, engagement, and growth. (Edutopia, 2014)

- That "Aha!" Moment of College or Career Readiness : See how one teacher helped his students connect to ideas about themselves and their futures through a program called Roadtrip Nation . (Edutopia, 2015)

Building 21st Century Skills Through Deeper Learning

- Defining Twenty-First Century Literacy : Discover how deeper-learning environments can help foster 21st century competencies. To learn more about deeper learning, check out Bob Lenz's Deeper Learning video and blog series . (Edutopia, 2013)

- 8 Strategies for Teaching Academic Language : Try out some of the eight strategies discussed in this post to help students develop the language skills they’ll need in college. (Edutopia, 2014)

- Critical Thinking Pathways : Explore six different pathways to practicing critical thinking within the context of authentic inquiry, PBL, or interdisciplinary (integrated) studies. (Edutopia, 2014)

- How to Help Students Think Abstractly : Explore exercises in figurative language and abstractions in order to develop college-level language and thinking skills. (Edutopia, 2012)

- Why Collaboration and Communication Matter : Consider ways to incorporate Common Core-aligned speaking and listening practice into group activities. (Edutopia, 2014)

- Study Habits and College Readiness : Watch a video about a lesson from a 9th grade class that helps students develop study skills, literacy skills, and mindsets to prepare for success in high school and college. (Teaching Channel, 2013)

- Yes, You Can Teach and Assess Creativity! : Find guidance to help you intentionally teach and assess creativity to help students learn more deeply, build confidence, and increase college readiness. (Edutopia, 2013)

Improving College Readiness Through PBL

- Stand and Deliver: The Role of Presentations in Project Based Learning : Explore how schools like Manor New Technology High School hone written and oral communication skills through PBL presentations to build college-and-career readiness. Read more about Manor New Technology High School in Edutopia’s Project-Based Learning: Success Start to Finish ." (P21, 2016)

- Experiencing Deeper Learning Through PBL : Watch a video profiling high school student Rahil, and learn more about how his experiences with project-based learning prepared him for college. (Edutopia, 2013)

- Can PBL Help Pave the Way to College Success? : Learn how one charter school network helps students become college-ready through an emphasis on project-based learning, student leadership, STEM education, and technology integration. (Edutopia, 2013)

- Want Your Students College Ready? Use PBL : Discover how well-implemented PBL taps into critical factors for college readiness. (Edutopia, 2011)

Increasing College Access

- Bridging the Gap Between Aspiration and Attainment in College Enrollment : Consider takeaways from an analysis by the Center for Public Education , including suggestions about how to bridge the gap between college enrollment aspiration and attainment. (Edutopia, 2014)

- Student Advocacy for Every Secondary School : Read about the role of student advocacy in helping students succeed and get to college. (Edutopia, 2013)

- How to Provide Guidance to First Generation College-Bound Students : Try out five strategies to better prepare first generation college-bound students for the college experience. (Edutopia, 2012)

- How to Provide College Planning and Counseling Support to Students of Color : Consider some advice to school counselors on giving balanced college-planning advice. (Edutopia, 2012)

- How College-Bound Students of Color Should Prepare for Life in a Predominantly White Campus : Explore conversation topics that can help students of color make a smooth transition to college life. (Edutopia, 2012)

- Five Steps to Widening the College Pipeline for African American and Latino Students : Transform classroom culture to help young people think about college as probable rather than possible. (Edutopia, 2012)

- College Readiness for ELLs : Discover ways to support English-language learners as they consider their future plans. (Colorin Colorado)

Helping Students Select and Apply to Colleges

- Gaming the College Admissions Process : Find out how games can help middle and high school students understand challenges and find solutions related to test review and the college application process. (Edutopia, 2014)

- A Strategy for Discovering and Describing Student Accomplishments : Prepare students for admissions essays by helping them examine the value of their experiences and accomplishments. (Edutopia, 2014)

- Choosing a College : Consider some advice about how to help students navigate around college myths to find their college match. (Edutopia, 2015)

- A Step-by-Step Guide to College Financial Aid : Help students navigate the process of applying for college financial aid, including information about FAFSA . (Edutopia, 2012)

Facilitating the Transition Beyond High School

- High School Support Through College : Learn about one school that extends support beyond high school to help students succeed in college. (Edutopia, 2016)

- Helpful Resources to Share With High School Graduates : Explore resources educators and parents can share with graduates to help them start planning ahead during the summer after graduation. (Edutopia, 2014)

- College Readiness Checklist for Parents : Use this college readiness checklist to make sure your high school grads are prepared for what's waiting for them on campus. (Edutopia, 2012)

- 9 Steps for Easing the Transition to College : Think through strategies to help teens with learning and attention issues prepare for the college transition. (Understood, 2014)

- College Board School Advisory Session Guides : Reference guides (especially the guide for grade 12) for session outlines that address topics about setting expectations for college and adjusting to college life; session outlines for grades 6 and up address other aspects of college readiness. (Big Future/College Board)

Downloads and Examples From Schools That Work

Edutopia's flagship series highlights practices and case studies from K-12 schools and districts that are improving the way students learn. Below, dive into real-world examples and practical downloads from schools that are preparing their students for college success.

College Prep: College Acceptance for Every Student

Learn how Urban Prep Charter Academy, Englewood Campus in Chicago, Illinois, ensures that all graduates are accepted to a four-year college or university. See how they conduct pride advisory classes to help students develop socially and emotionally and build college preparedness through all four years of high school. Then download information about their advisory curriculum and one of their college-readiness tools:

- College Planning Worksheet -- Use this worksheet to understand how students identify which colleges they'd like to attend.

- Pride Curriculum Map -- Learn more about the entire Pride Curriculum, which covers topics ranging from study skills to racism and financial literacy.

- Sophomore Pride Curriculum -- Take a look at the Pride Curriculum for sophomores, which covers topics such as identity development and responsible decision making.

Critical Thinking: A Path to College and Career

Review suggestions from educators at KIPP King Collegiate High School in San Lorenzo, California, on how to develop and assess critical-thinking skills to foster college readiness. Then check out how Kipp King addresses professional development on critical thinking , and explore some of the KIPP King school downloads to use them in your own school. Here are some highlights:

- Socratic Seminar Connectors : Download a one-page handout describing connector statements that students can use within the context of Socratic seminar discussions.

- Socratic Seminar Roles : Download a handout with specifics about possible roles and assignments of outer-circle members during Socratic seminars.

- Evaluating Seminar Statements : Download a handout that gives students practice evaluating seminar statements in advance of Socratic seminars and a reference list of connectors to help them formulate responses.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Health & Nursing

Courses and certificates.

- Bachelor's Degrees

- View all Business Bachelor's Degrees

- Business Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Healthcare Administration – B.S.

- Human Resource Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Marketing – B.S. Business Administration

- Accounting – B.S. Business Administration

- Finance – B.S.

- Supply Chain and Operations Management – B.S.

- Communications – B.S.

- User Experience Design – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree (from the School of Technology)

- Health Information Management – B.S. (from the Leavitt School of Health)

Master's Degrees

- View all Business Master's Degrees

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- MBA Information Technology Management

- MBA Healthcare Management

- Management and Leadership – M.S.

- Accounting – M.S.

- Marketing – M.S.

- Human Resource Management – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- Data Analytics – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Information Technology Management – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed. (from the School of Education)

Certificates

- Supply Chain

- Accounting Fundamentals

- Digital Marketing and E-Commerce

- View all Business Degrees

Bachelor's Preparing For Licensure

- View all Education Bachelor's Degrees

- Elementary Education – B.A.

- Special Education and Elementary Education (Dual Licensure) – B.A.

- Special Education (Mild-to-Moderate) – B.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary)– B.S.

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– B.S.

- View all Education Degrees

Bachelor of Arts in Education Degrees

- Educational Studies – B.A.

Master of Science in Education Degrees

- View all Education Master's Degrees

- Curriculum and Instruction – M.S.

- Educational Leadership – M.S.

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed.

Master's Preparing for Licensure

- Teaching, Elementary Education – M.A.

- Teaching, English Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Science Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Special Education (K-12) – M.A.

Licensure Information

- State Teaching Licensure Information

Master's Degrees for Teachers

- Mathematics Education (K-6) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grade) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- English Language Learning (PreK-12) – M.A.

- Endorsement Preparation Program, English Language Learning (PreK-12)

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– M.A.

- View all Technology Bachelor's Degrees

- Cloud Computing – B.S.

- Computer Science – B.S.

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – B.S.

- Data Analytics – B.S.

- Information Technology – B.S.

- Network Engineering and Security – B.S.

- Software Engineering – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration (from the School of Business)

- User Experience Design – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Technology Master's Degrees

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – M.S.

- Data Analytics – M.S.

- Information Technology Management – M.S.

- MBA Information Technology Management (from the School of Business)

- Full Stack Engineering

- Web Application Deployment and Support

- Front End Web Development

- Back End Web Development

3rd Party Certifications

- IT Certifications Included in WGU Degrees

- View all Technology Degrees

- View all Health & Nursing Bachelor's Degrees

- Nursing (RN-to-BSN online) – B.S.

- Nursing (Prelicensure) – B.S. (Available in select states)

- Health Information Management – B.S.

- Health and Human Services – B.S.

- Psychology – B.S.

- Health Science – B.S.

- Public Health – B.S.

- Healthcare Administration – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Nursing Post-Master's Certificates

- Nursing Education—Post-Master's Certificate

- Nursing Leadership and Management—Post-Master's Certificate

- Family Nurse Practitioner—Post-Master's Certificate

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner —Post-Master's Certificate

- View all Health & Nursing Degrees

- View all Nursing & Health Master's Degrees

- Nursing – Education (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Education (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration

- Master of Public Health

- MBA Healthcare Management (from the School of Business)

- Business Leadership (with the School of Business)

- Supply Chain (with the School of Business)

- Accounting Fundamentals (with the School of Business)

- Digital Marketing and E-Commerce (with the School of Business)

- Back End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Front End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Web Application Deployment and Support (with the School of Technology)

- Full Stack Engineering (with the School of Technology)

- Single Courses

- Course Bundles

Apply for Admission

Admission requirements.

- New Students

- WGU Returning Graduates

- WGU Readmission

- Enrollment Checklist

- Accessibility

- Accommodation Request

- School of Education Admission Requirements

- School of Business Admission Requirements

- School of Technology Admission Requirements

- Leavitt School of Health Admission Requirements

Additional Requirements

- Computer Requirements

- No Standardized Testing

- Clinical and Student Teaching Information

Transferring

- FAQs about Transferring

- Transfer to WGU

- Transferrable Certifications

- Request WGU Transcripts

- International Transfer Credit

- Tuition and Fees

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships

Other Ways to Pay for School

- Tuition—School of Business

- Tuition—School of Education

- Tuition—School of Technology

- Tuition—Leavitt School of Health

- Your Financial Obligations

- Tuition Comparison

- Applying for Financial Aid

- State Grants

- Consumer Information Guide

- Responsible Borrowing Initiative

- Higher Education Relief Fund

FAFSA Support

- Net Price Calculator

- FAFSA Simplification

- See All Scholarships

- Military Scholarships

- State Scholarships

- Scholarship FAQs

Payment Options

- Payment Plans

- Corporate Reimbursement

- Current Student Hardship Assistance

- Military Tuition Assistance

WGU Experience

- How You'll Learn

- Scheduling/Assessments

- Accreditation

- Student Support/Faculty

- Military Students

- Part-Time Options

- Virtual Military Education Resource Center

- Student Outcomes

- Return on Investment

- Students and Gradutes

- Career Growth

- Student Resources

- Communities

- Testimonials

- Career Guides

- Skills Guides

- Online Degrees

- All Degrees

- Explore Your Options

Admissions & Transfers

- Admissions Overview

Tuition & Financial Aid

Student Success

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Military and Veterans

- Commencement

- Careers at WGU

- Advancement & Giving

- Partnering with WGU

What is College Readiness?

- Classroom Strategies

- See More Tags

You might be surprised to learn that more than half of first-year college students say they aren’t prepared for college, despite being academically eligible to attend.

College readiness can ensure this doesn't happen.

By definition, college readiness is the set of skills, behaviors, and knowledge a high school student should have before enrollment in their first year of college. Counselors and teachers play a key role in making sure this happens and can help students find academic success in college. If you’re already a teacher, or studying to become one , it’s important to know how you can effectively prepare your students for college.

Let’s break it down.

Why is College Readiness Important?

The transition from high school to college is a major one. In many cases, students move away from home and embark on a new life chapter—both academically and personally. It’s crucial for parents and teachers to understand why college readiness is important so that they can better prepare students for a successful college experience even before enrollment.

Multiple studies show that college readiness improves a student’s chance of actually completing their degree. But the impact is even bigger than that. According to a report by American College Testing (ACT), high school graduates need to be college- and career-ready in order to have a properly skilled workforce that meets the demands of the 21st century.

Below are some ways teachers can equip their students for that next academic step.

How Can Teachers Measure College Readiness?

True college readiness requires both academic and real-world skills. In fact, the ability to solve problems, work in a team, and be resourceful are viewed by some experts as equally important to mastering mathematics and reading. So, while many colleges use ACT/SAT scores or a student’s high school GPA to measure college readiness, there are other indicators or “soft skills” that teachers can look for.

Essential Soft Skills for College Readiness

- Time management

- Critical thinking

- Communication

- Goal setting

- Collaboration

- Problem-solving

How Can I Prepare Students for College?

Here are five tips you can use to better equip your students for college success.

Focus on Executive Function Skills

Executive function refers to the mental skills that we use every day to learn and manage our daily lives. They include things such as memory, flexible thinking, and self-control. These skills can develop at different rates in different students. One way you can help support students in developing these skills is to establish a mindfulness routine that includes regular self-check-ins, self-reflection, intention setting, and gratitude practice.

Make the Classroom More Rigorous

It might be a challenge at first, but updates to the curriculum to include more intensive coursework is key to ensure students are well equipped with the broader set of strategies they’ll need for college. You can do this by implementing a challenging curriculum and assign longer, more complex assignments that involve things such as research, collaboration, and problem-solving.

Another thing you can do to help prepare your students for college is to teach them the value of extracurricular activities or after-school jobs. These things demonstrate to college admission officers that a student is well rounded and capable of handling the responsibilities that come with college.

Consider Social Aspects of College

Teachers can better prepare their students for college by teaching the social-emotional skills that they need to thrive in a post-secondary setting. Assigning group projects that promote collaboration and encouraging students to become involved in school activities, volunteer opportunities, or cultural events can encourage students to flex their interpersonal skills.

Teach Practical Skills

The best way to teach practical skills is to create coursework that allows students to put them into practice. Educators should look for opportunities to incorporate real-world skills into their instruction. For example, if you’re a math teacher, you can teach students how various math concepts relate to financial literacy, budgeting, or even preparing food.

Encourage Additional Preparation Resources

Prep courses and Advanced Placement (AP) classes are two of the best ways to academically prepare students for college. Not only do they give students a preview of what’s to come, but in many cases, students can earn college credit and get a head start on their college career.

Preparing students for the financial responsibility of college is important, too. The Department of Education’s financial aid toolkit offers multiple free resources for teachers and their students.

Every day, high school teachers help guide their students to academic and career success. If this important, highly rewarding role appeals to you, WGU can get you on the path to becoming a teacher. Learn more or contact us today !

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

{{item.date}}

{{item.preTitleTag}}

{{item.title}}

The university, for students.

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Student Experience

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Student Communities

Thinking and Analysis

Critical thinking skills.

The essence of the independent mind lies not in what it thinks, but in how it thinks. —Christopher Hitchens, author and journalist

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define critical thinking

- Describe the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to problem-solve

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to evaluate information

- Identify strategies for developing yourself as a critical thinker

Critical Thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s a “domain-general” thinking skill—not a thinking skill that’s reserved for a one subject alone or restricted to a particular subject area.

Great leaders have highly attuned critical thinking skills, and you can, too. In fact, you probably have a lot of these skills already. Of all your thinking skills, critical thinking may have the greatest value.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

| Critical Thinking IS | Critical Thinking is NOT |

|---|---|

| Skepticism | Memorizing |

| Examining assumptions | Group thinking |

| Challenging reasoning | Blind acceptance of authority |

| Uncovering biases |

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Activity: Self-Assess Your Critical Thinking Strategies

- Assess your basic understanding of the skills involved in critical thinking.

- Visit the Quia Critical Thinking Quiz page and click on Start Now (you don’t need to enter your name). Select the best answer for each question, and then click on Submit Answers. A score of 70 percent or better on this quiz is considering passing.

- Based on the content of the questions, do you feel you use good critical thinking strategies in college? In what ways might you improve as a critical thinker?

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination for the purpose of logically constructing reasoned perspectives.

What Is Logic, and Why Is It Important in Critical Thinking?

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community. The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him. In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

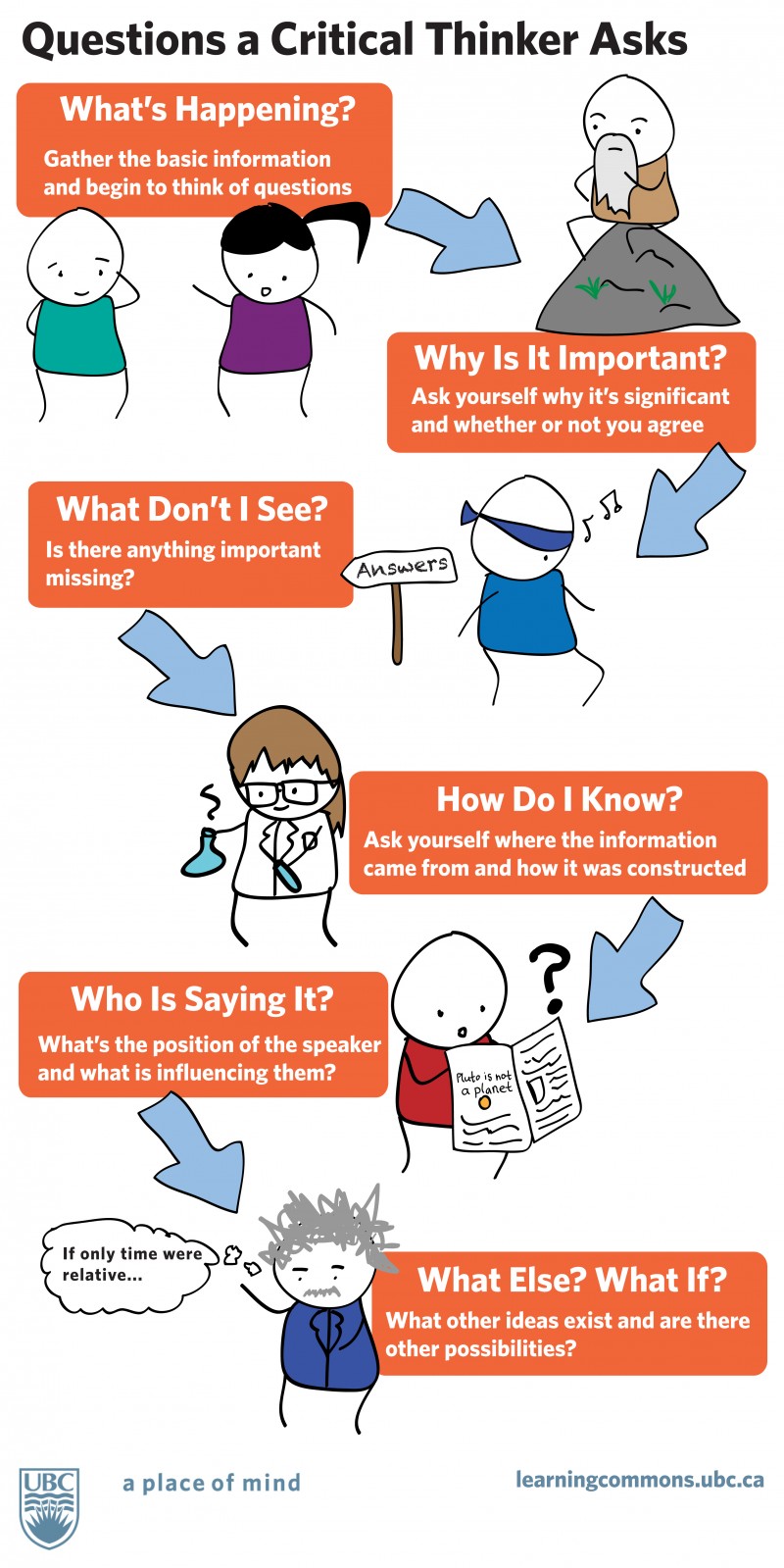

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving with Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in the relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support the roommate and help bring the relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your campus club has been languishing on account of lack of participation and funds. The new club president, though, is a marketing major and has identified some strategies to interest students in joining and supporting the club. Implementation is forthcoming.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember, too, to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker. If you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions.

| STRATEGIES | ACTION CHECKLIST | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define the problem | |

| 2 | Identify available solutions | |

| 3 | Select your solution |

Evaluating Information with Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

- Cultivate “habits of mind”

Read for Understanding Using Text Coding

When you read and take notes, use the text coding strategy . Text coding is a way of tracking your thinking while reading. It entails marking the text and recording what you are thinking either in the margins or perhaps on Post-it notes. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material.

With text coding, mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. Feel free to develop your own shorthand style when reading or taking notes. The following are a few options to consider using while coding text.

| Shorthand | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ! | Important |

| L | Learned something new |

| ! | Big idea surfaced |

| * | Interesting or important fact |

| ? | Dig deeper |

| ✓ | Agree |

| ≠ | Disagree |

See more text coding from PBWorks and Collaborative for Teaching and Learning .

Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The following video explains this strategy.

Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

Developing Yourself As a Critical Thinker

Critical thinking is a desire to seek, patience to doubt, fondness to meditate, slowness to assert, readiness to consider, carefulness to dispose and set in order; and hatred for every kind of imposture. —Francis Bacon, philosopher

Critical thinking is a fundamental skill for college students, but it should also be a lifelong pursuit. Below are additional strategies to develop yourself as a critical thinker in college and in everyday life:

- Reflect and practice : Always reflect on what you’ve learned. Is it true all the time? How did you arrive at your conclusions?

- Use wasted time : It’s certainly important to make time for relaxing, but if you find you are indulging in too much of a good thing, think about using your time more constructively. Determine when you do your best thinking and try to learn something new during that part of the day.

- Redefine the way you see things : It can be very uninteresting to always think the same way. Challenge yourself to see familiar things in new ways. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes and consider things from a different angle or perspective. If you’re trying to solve a problem, list all your concerns: what you need in order to solve it, who can help, what some possible barriers might be, etc. It’s often possible to reframe a problem as an opportunity. Try to find a solution where there seems to be none.

- Analyze the influences on your thinking and in your life : Why do you think or feel the way you do? Analyze your influences. Think about who in your life influences you. Do you feel or react a certain way because of social convention, or because you believe it is what is expected of you? Try to break out of any molds that may be constricting you.

- Express yourself : Critical thinking also involves being able to express yourself clearly. Most important in expressing yourself clearly is stating one point at a time. You might be inclined to argue every thought, but you might have greater impact if you focus just on your main arguments. This will help others to follow your thinking clearly. For more abstract ideas, assume that your audience may not understand. Provide examples, analogies, or metaphors where you can.

- Enhance your wellness : It’s easier to think critically when you take care of your mental and physical health. Try taking 10-minute activity breaks to reach 30 to 60 minutes of physical activity each day . Try taking a break between classes and walk to the coffee shop that’s farthest away. Scheduling physical activity into your day can help lower stress and increase mental alertness. Also, do your most difficult work when you have the most energy . Think about the time of day you are most effective and have the most energy. Plan to do your most difficult work during these times. And be sure to reach out for help . If you feel you need assistance with your mental or physical health, talk to a counselor or visit a doctor.

Activity: Reflect on Critical Thinking

- Apply critical thinking strategies to your life

Directions:

- Think about someone you consider to be a critical thinker (friend, professor, historical figure, etc). What qualities does he/she have?

- Review some of the critical thinking strategies discussed on this page. Pick one strategy that makes sense to you. How can you apply this critical thinking technique to your academic work?

- Habits of mind are attitudes and beliefs that influence how you approach the world (i.e., inquiring attitude, open mind, respect for truth, etc). What is one habit of mind you would like to actively develop over the next year? How will you develop a daily practice to cultivate this habit?

- Write your responses in journal form, and submit according to your instructor’s guidelines.

The following text is an excerpt from an essay by Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, “Thinking Critically and Creatively.” In these paragraphs, Dr. Baker underscores the importance of critical thinking—the imperative of critical thinking, really—to improving as students, teachers, and researchers. The follow-up portion of this essay appears in the Creative Thinking section of this course.

Thinking Critically and Creatively

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Resources for Critical Thinking

- Glossary of Critical Thinking Terms

- Critical Thinking Self-Assessment

- Logical Fallacies Jeopardy Template

- Fallacies Files—Home

- Thinking Critically | Learning Commons

- Foundation for Critical Thinking

- To Analyze Thinking We Must Identify and Question Its Elemental Structures

- Critical Thinking in Everyday Life

- "logike." Wordnik. n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- "Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online." Critical Thinking Gateway . St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Critical Thinking Skills. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of three students. Authored by : PopTech. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8tXtQp . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : http://www.oercommons.org/courses/learning-toolkit-critical-thinking/view . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Authored by : UBC Leap. Located at : https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of students putting post-its on wall. Authored by : Hector Alejandro. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7b2Ax2 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Foundations of Academic Success. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Components in a Comprehensive Definition of College Readiness

College readiness is a multi-faceted concept that includes factors both internal and external to the school environment. The model presented here emerges from a review of the literature and includes the skills and knowledge that can be most directly influenced by schools.

On this page:

Key cognitive strategies, academic knowledge and skills, academic behaviors, contextual skills and awareness.

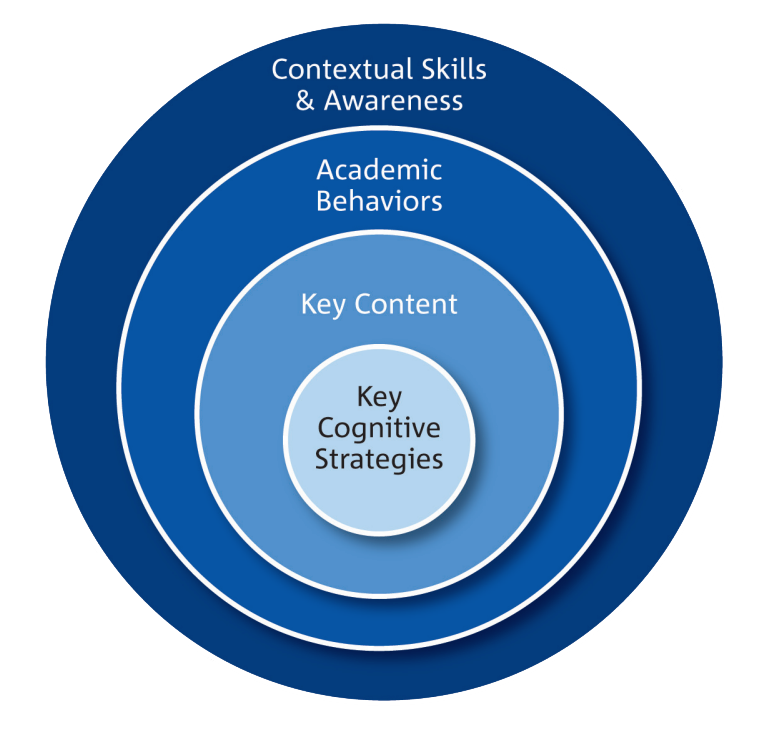

The definition of college readiness developed below relies on a framework of four interdependent skill areas (see Figure 1).

In practice, these various facets are not mutually exclusive or perfectly nested as portrayed in the model. They interact with one another extensively. For example, a lack of college knowledge often affects the decisions students make regarding the specific content knowledge they choose to study and master. Or a lack of attention to academic behaviors is one of the most frequent causes of problems for first-year students, whether they possess the necessary content knowledge and key cognitive strategies.

Figure 1: Facets of College Readiness

What the model argues for is a more comprehensive look at what it means to be college-ready, a perspective that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all of the facets contained in the model. This is the key point of this definition, that all facets of college readiness must be identified and eventually measured if more students are to be made college-ready.

The success of a well-prepared college student is built upon a foundation of key key cognitive strategies that enable students to learn content from a range of disciplines. Unfortunately, the development of key key cognitive strategies in high school is often overshadowed by an instructional focus on de-contextualized content and facts necessary to pass exit examinations or simply to keep students busy and classrooms quiet.

For the most part, state high-stakes standardized tests require students to recall or recognize fragmented and isolated bits of information. Those that do contain performance tasks are severely limited in the time the tasks can take and their breadth or depth. The tests rarely require students to apply their learning and almost never require students to exhibit proficiency in higher forms of cognition (Marzano, Pickering, & McTighe, 1993).

Several studies of college faculty members nationwide, regardless of the selectivity of the university, expressed near-universal agreement that most students arrive unprepared for the intellectual demands and expectations of postsecondary (Conley, 2003a). For example, one study found that faculty reported that the primary areas in which first-year students needed further development were critical thinking and problem solving (Lundell, Higbee, Hipp, & Copeland, 2004).

The term “key cognitive strategies” was selected for this model to describe the intelligent behaviors necessary for college readiness and to emphasize that these behaviors need to be developed over a period of time such that they become ways of thinking, habits in how intellectual activities are pursued. In other words, key cognitive strategies are patterns of intellectual behavior that lead to the development of cognitive strategies and capabilities necessary for college-level work. The term key cognitive strategies invokes a more disciplined approach to thinking than terms such as “dispositions” or “thinking skills.” The term indicates intentional and practiced behaviors that become a habitual way of working toward more thoughtful and intelligent action (Costa & Kallick, 2000).

The specific key cognitive strategies referenced in this paper are those shown to be closely related to college success. They include the following as the most important manifestations of this way of thinking:

- Intellectual openness The student possesses curiosity and a thirst for deeper understanding, questions the views of others when those views are not logically supported, accepts constructive criticism, and changes personal views if warranted by the evidence. Such openmindedness helps students understand the ways in which knowledge is constructed, broadens personal perspectives and helps students deal with the novelty and ambiguity often encountered in the study of new subjects and new materials.

- Inquisitiveness The student engages in active inquiry and dialogue about subject matter and research questions and seeks evidence to defend arguments, explanations, or lines of reasoning. The student does not simply accept as given any assertion that is presented or conclusion that is reached, but asks why things are so.

The student identifies and evaluates data, material, and sources for quality of content, validity, credibility, and relevance. The student compares and contrasts sources and findings and generates summaries and explanations of source materials.

The student constructs well-reasoned arguments or proofs to explain phenomena or issues; utilizes recognized forms of reasoning to construct an argument and defend a point of view or conclusion; accepts critiques of or challenges to assertions; and addresses critiques and challenges by providing a logical explanation or refutation, or by acknowledging the accuracy of the critique or challenge.

The student analyzes competing and conflicting descriptions of an event or issue to determine the strengths and flaws in each description and any commonalities among or distinctions between them; synthesizes the results of an analysis of competing or conflicting descriptions of an event or issue or phenomenon into a coherent explanation; states the interpretation that is most likely correct or is most reasonable, based on the available evidence; and presents orally or in writing an extended description, summary, and evaluation of varied perspectives and conflicting points of view on a topic or issue.

The student knows what type of precision is appropriate to the task and the subject area, is able to increase precision and accuracy through successive approximations generated from a task or process that is repeated, and uses precision appropriately to reach correct conclusions in the context of the task or subject area at hand.

The student develops and applies multiple strategies to solve routine problems, generate strategies to solve non-routine problems, and applies methods of problem solving to complex problems requiring method-based problem solving. These key cognitive strategies are broadly representative of the foundational elements that underlie various “ways of knowing.”

These are at the heart of the intellectual endeavor of the university. They are necessary to discern truth and meaning as well as to pursue them. They are at the heart of how postsecondary faculty members think, and how they think about their subject areas. Without the capability to think in these ways, the entering college student either struggles mightily until these habits begin to develop or misses out on the largest portion of what college has to offer, which is how to think about the world.

Successful academic preparation for college is grounded in two important dimensions — key cognitive strategies and content knowledge. Understanding and mastering key content knowledge is achieved through the exercise of broader cognitive skills embodied within the key cognitive strategies. With this relationship in mind, it is entirely proper and worthwhile to consider some of the general areas in which students need strong grounding in content that is foundational to the understanding of academic disciplines. The case for the importance of challenging content as the framework for developing thinking skills and key cognitive strategies has been made elsewhere and will not be repeated in depth here (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000).

In order to illustrate the academic knowledge and skills necessary for college success, a brief discussion of the key structures, concepts, and knowledge of core academic subjects is presented below. This presentation is not a substitute for a comprehensive listing of essential academic knowledge and skills. A more complete exposition is contained in “Understanding University Success,” produced by Standards for Success through a three-year study in which more than 400 faculty and staff members from 20 research universities participated in extensive meetings and reviews to identify what students must do to succeed in entry-level courses at their institutions (Conley, 2003a). These findings have been confirmed in subsequent studies.

This overview begins with two academic skill areas that have repeatedly been identified as being centrally important to college success: writing and research. This is followed by brief narrative descriptions of content from a number of core academic areas.

Overarching Academic Skills

Writing is the means by which students are evaluated at least to some degree in nearly every postsecondary course. Expository, descriptive, and persuasive writing are particularly important types of writing in college. Students are expected to write a lot in college and to do so in relatively short periods of time.

Students need to know how to pre-write, how to edit, and how to re-write a piece before it is submitted and, often, after it has been submitted once and feedback has been provided. College writing requires students to present arguments clearly, substantiate each point, and utilize the basics of a style manual when constructing a paper. College-level writing is largely free of grammatical, spelling, and usage errors.

College courses increasingly require students to be able to identify and utilize appropriate strategies and methodologies to explore and answer problems and to conduct research on a range of questions. To do so, students must be able to evaluate the appropriateness of a variety of source material and then synthesize and incorporate the material into a paper or report. They must also be able to access a variety of types of information from a range of locations, formats, and source environments.

Core academic subjects knowledge and skills

The knowledge and skills developed in entry-level English courses enable students to engage texts critically and create well written, organized, and supported work products in both oral and written formats. The foundations of English include reading comprehension and literature, writing and editing, information gathering, and analysis, critiques and connections.

To be ready to succeed in such courses, students need to build vocabulary and word analysis skills, including roots and derivations. These are the building blocks of advanced literacy. Similarly, students need to utilize techniques such as strategic reading that will help them read and understand a wide range of non-fiction and technical texts. Knowing how to slow down to understand key points, when to re-read a passage, and how to underline key terms and concepts strategically so that only the most important points are highlighted are examples of strategies that aid comprehension and retention of key content.