Essays About Character: Top 5 Examples and 9 Prompts

If you’re writing an essay about character, below are helpful examples of essays about character with prompts to inspire you further.

When we say that a person has character, we usually refer to one’s positive qualities such as moral fiber, spiritual backbone, social attitudes, mental strength, and beliefs. But not to be mistaken with mere personality, character goes beyond the sum of all good traits. Instead, it demonstrates and applies these qualities in interacting with people, acting on responsibilities, and responding to challenges.

Character, hence, cannot be evaluated by a single action or event. Instead, it manifests in a pattern and through consistency.

Read on to find essays and prompts to help you create an essay with rich insights.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. How 5 CEOs Hire For Character by Chris Fields

2. the character of leadership by brian k. cooper et. al, 3. when proof of good moral character helps an immigration application—or doesn’t by ilona bray, j.d., 4. what are the 24 character strengths by sherri gordon, 5. the five character traits the best investors share by richard thalheimer , 9 writing prompts for essays about character, 1. what are your character strengths, 2. the importance of character, 3. how household chores develop a child’s character, 4. how challenges shape your character, 5. character education in schools, 6. character analysis, 7. character vs. personality , 8. why psychologists study character, 9. choosing people for your character reference .

“You have to be a good person with a good heart. Of course, you have to be qualified, educated and skilled, that goes without saying – or it should – but your next candidate can’t be a bad person because CEOs are looking for character.”

The essay compiles insights from famous billionaire CEOs who underscore the importance of recruiting people with good character. It shows the upward trend among companies seeking qualifications beyond education and professional experience and looking more into the heart of people. You might also be interested in these essays about courage .

“…[L]eadership that achieves results goes beyond how to be, and becomes how to do; this type of leadership is all about character. So in other words, in order to get things done personally and organizationally, one first needs to get in touch with his or her character.”

Character in leadership could translate to benefits beyond the organization, society, or the world. The essay is based on a study of the three underlying dimensions of leadership character: universalism, transformation, and benevolence.

“Demonstrating good moral character is an extremely important part of many immigration cases, but it is not required in all of them. In fact, providing proof of your accomplishments to the court could hurt your immigration case in some instances.”

Showing good moral character is a common requirement for immigrants seeking to be naturalized citizens in a different country. This article gets into the nitty gritty on how one can best prove good moral character when facing immigration officers.

“Knowing a person’s character strengths provides a lens through which psychologists, educators, and even parents can see not only what makes a person unique, but also understand how to help that person build on those strengths to improve situations or outcomes.”

The concept of character strengths aims to help people focus on their strengths to lead healthy and happy life. Understanding character strengths meant being more equipped to use these strengths to one’s advantage, whether toward academic access or overcoming adversities.

“… [Y]ou have to be able to pick the right stocks. That’s where talent, intellect, knowledge and common sense come in. Of course, if you can’t control your emotions, and you get fearful and sell every time the market drops, all that talent, knowledge, intellect and common sense go out the window.”

Having an eye for the right stocks requires developing five character traits: talent, intellect, knowledge, common sense, and a bias to action. All these could be honed by sharpening one’s knowledge of the current news and financial trends. Developing character as a stock investor also requires a daily routine that allows one to exercise analytical skills.

Check out these great prompts about character:

What are the positive character traits you think you have that many people also see in you? List down these strengths and dive deep into each one. To start, you may look into the 24 strengths highlighted in one of the essay examples. Then, identify which ones best suit you. Finally, elaborate on how you or the people around you have benefitted from each.

In a world where many are motivated by fame and fortune, how can you convince people that being kind, honest, and courageous trump all life’s material, fleeting desires? Turn this essay into an opportunity to call more people to build good character and keep out of bad habits and actions.

Tasking children doing household chores can offer benefits beyond enjoying a sparkly clean home. In the long-term, it builds children’s character that can help them lead healthy and happy life. For this prompt, lay down the top benefits children will gain from performing their chores and responsibilities in the household.

Our best selves reveal themselves in the darkest times. You can easily say that obstacles are the actual test of our character. So, first, narrate a challenging experience you had in your life. Then, describe how you turned this bad period around to your advantage to strengthen your mind, character, and resilience.

Schools play a vital role in training children to have a strong-minded character and contribute to the good of society. As such, schools integrate character education into their curriculum and structure. In your essay, narrate how much your school values character building. Elaborate on how it teaches bad actions, such as bullying or cheating, and good virtues, such as respecting others’ culture, traditions, and rights.

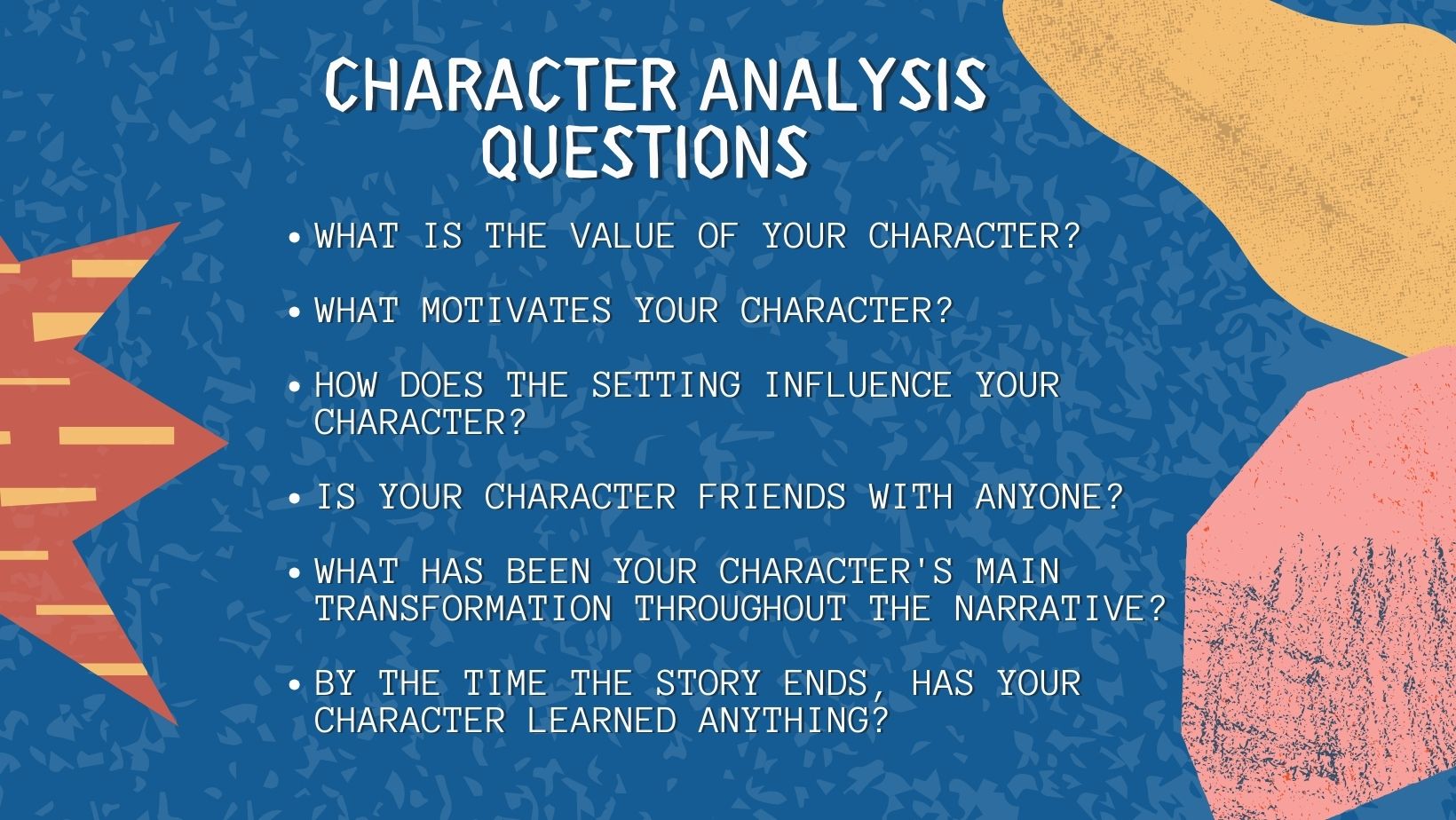

Pick a character you adore, whether from a novel or a book. Then, write an analysis of their traits and how these fit into their assigned role in the story. Of course, as in every character analysis, narrate their character transformation. So you have to identify key turning points and realizations that prompted the changes in their character, role, values, and beliefs.

Both your character and personality make you a unique individual. But they have different definitions and uses that make them independent of each other. In your essay, identify these differences and answer which has the most significant impact on your life and which one you should focus on.

Psychologists study characters to know how and why they change over time. This helps them enhance their understanding of human motivation and behavior. In your essay, answer to a greater extent how studying character drive more people to thrive in school, work, or home. Then, compile recent studies on what has been discovered about developing character and its influences on our daily lives.

A good character reference can help you secure a job you’re aiming for. So first, identify the top qualities employers look for among job seekers. Then, help the reader choose the best people for their character reference. For students, for example, you may recommend they choose their former professors who can vouch for their excellent work at school.

To make sure your readers are hooked from beginning to end, check out our essay writing tips ! If you’re thinking about changing your essay topic, browse through our general resource of essay writing topics .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Are the 24 Character Strengths?

Everyone has varying degrees of these positive traits

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

- Character Strengths

People often look for good character in others, whether they are employees, students, friends, or potential dating partners. According to positive psychology , good character is exemplified by 24 widely valued character strengths.

Learn how the idea of these character strengths came about, how they are organized, and how to assess which strengths a person may possess. We also share ways to maximize one's character strengths, enabling a person to live to their fullest potential.

History of the 24 Character Strengths

The notion of character strengths was first introduced by psychologists Martin Seligman and Christopher Peterson. Seligman and Neal Mayerson, another psychologist, created the Values In Action (VIA) Institute on Character, which uses the VIA Inventory of Strengths developed by Peterson to identify people's positive character strengths.

A character strength inventory can identify both a person's strengths and ways they can use those strengths in their life. Building on one's positive character strengths can help them improve their life and emotional well-being , as well as address the challenges and difficulties they are facing.

It's also important to note that the 24 character strengths that these tools identify have been studied across cultures. These strengths are important components of individual and social well-being globally, with different strengths predicting different outcomes.

For instance, intellectual, emotional, and interpersonal character strengths can help a person better cope with work-related stressors, ultimately impacting their level of job satisfaction. Interventions that help build character strengths can also improve the psychological well-being of people with chronic illnesses .

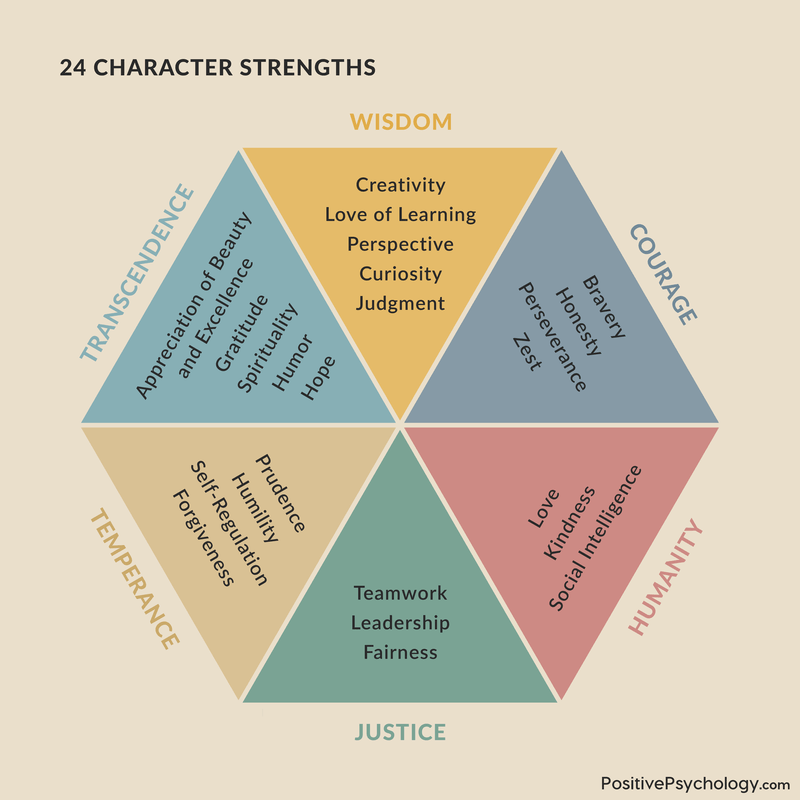

Classification of Character Strengths

The 24 character strengths are divided into six classes of virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. Here is a closer look at the six virtues and the positive character strengths that are grouped with each of them.

Those who score high in the area of wisdom tend to have character strengths that lead them to acquire knowledge and use it in creative and useful ways. The core wisdom character strengths are:

- Creativity : Thinking of new ways to do things

- Curiosity : Taking an interest in a wide variety of topics

- Open-mindedness : Examining things from all sides ; thinking things through

- Love of learning : Mastering new topics, skills, and bodies of research

- Perspective : Being able to provide wise counsel to others; looking at the world in a way that makes sense

People who score high in courage have emotional character strengths that allow them to accomplish goals despite any opposition they face—whether internal or external. The character strengths associated with courage are:

- Honesty : Speaking the truth; being authentic and genuine

- Bravery : Embracing challenges, difficulties, or pain; not shrinking from threat

- Persistence : Finishing things once they are started

- Zest : Approaching all things in life with energy and excitement

Those who score high in humanity have a range of interpersonal character strengths that involve caring for and befriending others . These core character strengths are:

- Kindness : Doing favors and good deeds

- Love : Valuing close relations with others

- Social intelligence : Being aware of other people's motives and feelings

People who are strong in justice tend to possess civic strengths that underscore the importance of a healthy community. The character strengths in the justice group are:

- Fairness : Treating all people the same

- Leadership : Organizing group activities and making sure they happen

- Teamwork : Working well with others as a group or a team

Those who score high in temperance tend to have strengths that protect against the excesses in life. These strengths are:

- Forgiveness : Forgiving others who have wronged them

- Modesty : Letting one's successes and accomplishments stand on their own

- Prudence : Avoiding doing things they might regret; making good choices

- Self-regulation : Being disciplined ; controlling one's appetites and emotions

Transcendence

People who are strong in transcendence tend to forge connections with God, the universe, or religions that provide meaning, purpose, and understanding. The core positive character strengths associated with transcendence are:

- Appreciation of beauty : Noticing and appreciating beauty and excellence in everything

- Gratitude : Being thankful for the good things; taking time to express thanks

- Hope : Expecting the best; working to make it happen; believing good things are possible

- Humor : Making other people smile or laugh; enjoying jokes

- Religiousness: Having a solid belief about a higher purpose and meaning of life

Positive Character Traits List

The 24 positive character strengths are split into six virtue classes:

- Wisdom : Creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective

- Courage : Honesty, bravery, persistence, zest

- Humanity : Kindness, love, social intelligence

- Justice : Fairness, leadership, teamwork

- Temperance : Forgiveness, modesty, prudence, self-regulation

- Transcendence : Appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, religiousness

How Character Strengths Are Assessed

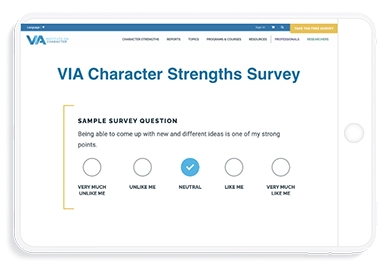

A person's character strengths can be determined using one of two inventories. The VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) is for people aged 18 and older, while the VIA Inventory of Strengths—Youth Version (VIA-Youth) is designed for kids and teens aged 10 to 17.

The goal behind the classification of strengths is to focus on what is right about people rather than pathologize what is wrong with them. It's important to point out that people typically have varying degrees of each positive character strength. In other words, they will be high in some strengths, average in some, and low in others.

There is no single indicator of good character. Instead, a person's character should be viewed across a continuum.

The VIA Institute on Character stresses that the traits not included as signature strengths are not necessarily weaknesses, but rather lesser strengths in comparison to the others. Likewise, the top five strengths should not be rigidly interpreted because there are usually no meaningful differences in their magnitudes.

Uses for Character Strengths

One of the main reasons for assessing positive character strengths is to use this information to better understand, identify, and build on these strengths. For example, identifying and harnessing character strengths can help young people experience greater academic success. It can also help people increase feelings of happiness .

Knowing a person's character strengths provides a lens through which psychologists, educators, and even parents can look. It helps them see not only what makes a person unique but also enables them to better understand how to help that person build on those strengths to improve their situations or outcomes.

For example, one strategy involves encouraging people to use their signature strengths in a new way each week. Studies have found that taking this approach can lead to increases in happiness and decreases in depression . Another approach involves focusing on a person's lowest-rated character strengths in an attempt to enhance those areas of their lives.

Research has demonstrated that traumatic events can change a person's character strengths, as evidenced by studies investigating the effects of shooting tragedies. Other studies note that some character strengths can help people better cope with these types of situations, such as was found with people who lived through Hurricane Michael, a category 5 storm.

Overall, determining and using one's character strengths has the potential to improve their health and well-being, enhance their job performance, and improve their academic success. It's also a more positive way of viewing and improving oneself than focusing on their shortcomings and faults.

Lavy S. A review of character strengths interventions in twenty-first-century schools: their importance and how they can be fostered . App Res Qual Life . 2019;15:573-596. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9700-6

Wagner L. Good character is what we look for in a friend: Character strengths are positively related to peer acceptance and friendship quality in early adolescents . J Early Adolesc . 2018;39(6):864-903. doi:10.1177/0272431618791286

VIA Institute on Character. About .

Harzer C, Ruch W. The relationships of character strengths with coping, work-related stress, and job satisfaction . Front Psychol . 2015;6:165. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00165

McGrath RE. Character strengths in 75 nations: An update . J Posit Psychol . 2015;10(1):41-52. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.888580

Yan T, Chan C, Ming Chow K, Zheng W, Sun M. A systematic review of the effects of character strengths-based intervention on the psychological well-being of patients suffering from chronic illnesses . J Adv Nurs . 2020;76(7):1567-1580. doi:10.1111/jan.14356

Najderska M, Cieciuch J. The structure of character strengths: variable- and person-centered approaches . Front Psychol . 2018;9:153. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00153

Wagner L, Ruch W. Good character at school: positive classroom behavior mediates the link between character strengths and school achievement . Front Psychol . 2015;6:610. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00610

VIA Institute on Character. Frequently asked questions .

Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The impact of signature character strengths interventions: A meta-analysis . J Happiness Stud . 2018;10:1179-1196. doi:10.1007/s10902-018-9990-2

Abdullah Basurrah A, O'Sullivan D, Seeho Chan J. A character strengths intervention for happiness and depression in Saudi Arabia: A replication of Seligman et al.'s (2005) study . Midd East J Pos Psychol . 2020;6:41-72.

Schueller SM, Jayawickreme E, Blackie LER, Forgeard MJC, Roepke AM. Finding character strengths through loss: An extension of Peterson and Seligman (2003) . J Pos Psycho l. 2015;10(1):53-63. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.920405

Raney AA, Ai AL, Paloutzian RF. Faith factors, character strengths, and depression following Hurricane Michael . Int J Psychol Religion . 2022;32(4):330-346. doi:10.1080/10508619.2022.2029045

By Sherri Gordon Sherri Gordon, CLC is a published author, certified professional life coach, and bullying prevention expert. She's also the former editor of Columbus Parent and has countless years of experience writing and researching health and social issues.

Why Strong Character Is a Foundation of Resilience

This interview with dr. david wang explores character development & resilience..

Posted March 7, 2019

- What Is Resilience?

- Take our Resilience Test

- Find a therapist near me

Today I continue in my series of interviews with experts on how resilience —one of the major themes of my book, A Walking Disaster: What Surviving Katrina and Cancer Taught Me About Faith and Resilience —connects to their area of study. Today’s interview is on the subject of character development and resilience and features Dr. David C. Wang, Associate Professor of Psychology at the Rosemead School of Psychology, Biola University. A licensed psychologist, he also serves as a pastor of spiritual formation at One Life City Church, as well as at several non-profits in various capacities.

JA: How do you personally define character development?

DW: People have been thinking about character and character development for millennia, and it has inspired some very thoughtful scholarship in quite a number of academic disciplines. For example, Rachana Kamtekar, professor of philosophy at Cornell University, speaks of how contemporary virtue ethicists tend to speak of virtue as a sort of harmony between what we rationally believe to be the right thing to do and our natural affections or natural desire to do it. What I like about this thought is that it acknowledges the unflattering reality that just because we know what the right thing is to do, doesn’t necessarily mean that it is also what we fundamentally want to do, nor that it is even what we ultimately choose to do. And so, Aristotle reminds us in the Nicomachean Ethics that the goal of virtuous character isn’t just to know what virtue is but to become good. So, putting this all together, I understand character development to be the journey we take to not only know what is good, but to choose what is good, and (this just might be the hardest part of it all) to earnestly and wholeheartedly desire and take pleasure in what is good.

JA: How did you first get interested in studying character development?

DW: In addition to my academic and clinical work, I’m also a pastor of a local congregation. And ironically, what had gotten me initially interested in studying character development was a few really horrible ministry experiences early on in life. While religious education is generally understood to cultivate character, so many of us (myself included) are profoundly familiar with the pain inflicted by thoroughly religiously educated individuals who yet suffer from major character deficits. How can someone who knows the good so well still have such a capacity to do evil? This was the question that has led me to where I am today and where I hope to be in the future.

JA: What is the connection between character development and resilience?

DW: Linda Zagzebski, Chair of Philosophy of Religion and Ethics at the University of Oklahoma, described intellectual virtues as “forms of motivation to have cognitive contact with reality.” Although she was speaking here of intellectual virtues in particular, I think it would be fair to say that there is something about virtue, in general, and how it cultivates in us a disposition towards facing or having contact with reality—whatever it might be (e.g., the reality of ourselves, of others, of our situation, etc.). And here is where I believe the connection between character development and resilience lies. Resilience can be understood as a person’s capacity to overcome difficulty, or to recover and ‘bounce back’ from trauma . Unfortunately, many people think that the key to overcoming difficulty is to simply to maintain a positive attitude. But the problem is that this positive attitude also needs to be in contact with the reality of the situation, which is often quite bleak. If it is not, this positivity can turn rigid and degenerate into avoidance, which is what research has found to be a powerful predictor of poor adjustment post-trauma. Thus, character is the glue that binds positive attitudes and behavior with a realism that is grounded in the needs and realities of a broken situation.

JA: What are some ways people might cultivate character strengths to help them live more resiliently?

DW: Continuing what I was speaking on previously, I think the key to cultivating character strengths is the courage to face reality: the reality of ourselves, the reality of others, the reality of our situation. And this is why I believe themes such as guilt and shame are so counterproductive in the cultivation of character. People use guilt and shame to shape behavior because they are so effective. Guilt motivates us through fear , and shame leads us to cover up and hide our true selves. But virtue is not just about doing what is good, but also earnestly desiring it as well. And we can’t do the latter through fear and hiding. We can’t do the latter without first coming to terms with the reality of ourselves.

JA: Can you share what you’re working on these days related to character development?

DW: I’m leading a series of grant projects funded by the John Templeton Foundation on the character and spiritual development of seminary students—individuals who will one day become the leaders of local churches and parishes, denominations, and non-profit organizations (click here and here for more information). We have partnered with the Association of Theological Schools and are presently ramping up efforts to conduct longitudinal research on the character and spiritual development of seminary students enrolled at 14 Evangelical, Roman Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and historically African-American seminaries. We are excited to empirically investigate topics such as 1) to what extent does religious education shape character, 2) what about religious education shapes character, and 3) what is the relationship, if any, between spiritual development and character development?

JA: Anything else you’d care to share?

DW: Despite all the tragedy that we witness and hear about, I am continually amazed at how remarkably resilient and virtuous people can be—and often from people that garner little attention from the news, from people that we might least expect. I am grateful for opportunities to bring to light the stories and realities of some of these individuals, so that we may all be inspired and edified.

Jamie Aten , Ph.D. , is the founder and executive director of the Humanitarian Disaster Institute at Wheaton College.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being Essay (Article)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Character strengths, definition of well-being, relationship between character strengths and well-being, positive psychological interventions, practical application in personal life.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, a new branch of psychology emerged, which was named positive psychology. This new field of psychology aims at studying people’s happiness and the ways of achieving it (Parks & Titova, 2016). Positive psychology focuses on people’s positive experiences, character strengths, and positive institutions, such as workplaces and families (Harzer, 2016). These constituents, as well as their interrelation, influence individuals’ well-being (Harzer, 2016). One way of increasing one’s happiness is to recognize and utilize one’s character strengths (Parks & Titova, 2016). This paper aims at identifying the key character strengths and their influence on people’s well-being. The knowledge of personal qualities that contribute to one’s feeling of happiness helps one to develop those traits and enhance one’s life satisfaction.

One of the key concepts used in positive psychology is character strengths. They are positive personal qualities that are stable but liable to changes through training (Gander, Hofmann, Proyer, & Ruch, 2019). Researchers distinguish 24 character strengths that are considered valuable in many cultures and contribute to greater life satisfaction (Freidlin, Littman-Ovadia, & Niemiec, 2017). Some of them are curiosity, bravery, honesty, forgiveness, self-regulation, gratitude, and spirituality (Wagner, Gander, Proyer, & Ruch, 2019). A person demonstrates these character strengths through feelings, thoughts, and behaviors (Harzer, 2016). For example, if a student is listening to the lecturer, he may be interested in the subject, thus showing curiosity through feeling. If he thinks about asking the lecturer for more details on the topic, he demonstrates this strength through thought. When he approaches the teacher after the class to ask for more information, his curiosity manifests through behavior.

Character strengths are basic qualities that contribute to the development of more complex behaviors. They provide the basis for talents, interests, skills, values, and resources (Niemiec, 2017). For example, to develop a talent, which is something that a person is inherently good at, one should exercise self-regulation, perseverance, and zest (Niemiec, 2017). While talents and skills may worsen, resources, such as friends or family, maybe lost over time, character strengths always remain in a person’s nature (Niemiec, 2017). For this reason, it would be beneficial for anyone to invest time and effort in developing positive personality traits.

There are several subgroups of character strengths, depending on the degree to which they are present within a person. Signature strengths are qualities that are the most characteristic of an individual and are used the most naturally and frequently (Niemiec, 2017). Happiness strengths are associated with life satisfaction and include love, zest, gratitude, hope, and curiosity (Niemiec, 2017). Middle strengths are supplemental to signature strengths, while lower strengths are traits that are underdeveloped and, therefore, used rarely (Niemiec, 2017). Finally, there are lost strengths that disappeared from one’s personality due to some external influences, such as an authority figure or cultural restrictions (Niemiec, 2017). This subdivision implies that, initially, a person possesses all positive traits, but over time, some of them become dominant while other ones remain underdeveloped or dormant.

Generally, character strengths improve well-being, but scholars have different opinions as to what is considered well-being. There are two points of view on this concept: hedonic and eudaimonic (Harzer, 2016). Hedonists believe that well-being is determined by “pleasures and happiness” (Harzer, 2016, p. 310). In psychology, it is usually called subjective well-being, meaning “frequent positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and high life satisfaction” (Harzer, 2016, p. 310). The eudaimonic point of view is different since it suggests that personal growth and the fulfillment of one’s potential is the key to life satisfaction; psychologists call this perspective psychological well-being (Harzer, 2016). These two viewpoints focus on different things when defining factors contributing to one’s happiness.

However, the most comprehensive explanation of well-being was proposed by Seligman. He argued that this concept comprised both hedonic and eudaimonic elements (Wagner et al., 2019). According to Seligman, well-being consists of positive emotions, positive relationships, engagement, accomplishment, and meaning (as cited in Wagner et al., 2019). Engagement means being completely focused on a task; meaning is leading a purposeful life; accomplishment means having goals and ambitions (Wagner et al., 2019). If a person pursues each of these components, he or she will experience overall well-being.

Numerous studies show that character strengths contribute to both subjective and psychological well-being. Some of them have a greater influence on life satisfaction, for example, love, gratitude, curiosity, hope, and zest (Harzer, 2016). Other character strengths, such as modesty, creativity, appreciation, and love of learning, have less impact, but none of them has a negative effect on people’s happiness (Harzer, 2016). The most important traits for subjective and psychological well-being are zest, hope, and curiosity (Harzer, 2016). Zest means feeling full of energy; hope is believing that something good will happen in the future; curiosity implies expressing interest and looking for new experiences (Harzer, 2016). Thus, it makes sense to cultivate at least these three qualities in order to achieve greater well-being.

There is also an association between underuse and overuse of particular character strengths as compared to their optimal use. The study by Freidlin et al. (2017) showed that when positive traits were utilized moderately, they contributed to individuals’ well-being. However, excessive or insufficient use of character strengths was likely to lead to mental health impairments, such as depression or social anxiety disorder (Freidlin et al., 2017). At the same time, underuse of character strengths had a greater probability of negative outcomes than the overuse of them (Freidlin et al., 2017). For example, people who underused self-regulation, zest, and humor, and overused humility were more likely to experience social anxiety (Freidlin et al., 2017). These findings imply that individuals should make efforts to recognize their character strengths and the extent to which they are developed. Further improvement of underdeveloped positive traits may enhance people’s well-being.

Research into the relationship between character strengths and well-being is important not only because it helps to understand how personality traits influence the experience of happiness. Another reason for its importance is that it provides individuals with ideas of how their well-being can be improved. Recent studies show that personality is not something unchangeable, so personal qualities may be intentionally developed or eroded (Niemiec, 2017). Based on this knowledge, researchers have begun to create techniques designed to help people increase their happiness, and these methods are referred to as positive psychological interventions (PPIs) (Parks & Titova, 2016). The purpose of PPIs is to help people cope with their negative emotions and enhance their positive feelings for a long time (Parks & Titova, 2016). The interventions involve different activities that are intended to improve particular character strengths. For example, to improve well-being through the development of gratitude, people could be asked to keep a log with reflections about their feeling grateful for something (Parks & Titova, 2016). PPIs can be self-administered, which makes them a convenient tool for people who aim at improving their well-being through self-development.

Now that I have identified the purpose of positive psychology and the role of personal qualities in enhancing well-being, I can determine how these concepts relate to my life. First of all, research into positive psychology has helped me to understand what makes people feel happy. Not material things or money but positive emotions, the experience of flow states, close relationships, a sense of purpose, and ambitions contribute to one’s life satisfaction (Wagner et al., 2019). It means that in order to improve my well-being, I need to increase the amount of these positive things in my life.

Furthermore, this research has helped me to understand the significance of personality traits for one’s feeling of happiness. Given this knowledge, I can take action to identify my signature strengths, as well as qualities that I need to develop to enhance my well-being. To perform this, I can take a test based on the Values-in-Action (VIA) classification of strengths, which is commonly used for assessing personality traits (Wagner et al., 2019). As soon as I know what qualities are my signature strengths and what my lower strengths are, I will be able to search for self-administered PPIs that may help me to improve my underdeveloped strengths and make my life more meaningful.

To sum up, the aim of positive psychology is to help people enhance their happiness by increasing the number of positive experiences. One of its key topics is character strengths, that is, 24 positive personality traits that contribute to an individual’s well-being. Since personal qualities are liable to changes, people can enhance their life satisfaction by cultivating their underdeveloped character strengths. Research into the relationship between personality traits and well-being has helped me to understand how I can become happier and more satisfied with life. I can also share this knowledge with others, thus contributing to the overall public well-being.

Freidlin, P., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Niemiec, R. M. (2017). Positive psychopathology: Social anxiety via character strengths underuse and overuse. Personality and Individual Differences, 108 , 50-54.

Gander, F., Hofmann, J., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2019). Character strengths – stability, change, and relationships with well-being changes. Applied Research in Quality of Life. Web.

Harzer, C. (2016). The eudaimonic of human strengths: The relations between character strengths and well-being. In J. Vittersø (Ed.), International handbooks of quality-of-life (pp. 307-322). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Niemiec, R. M. (2017). Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners . Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe Publishing.

Parks, A. C., & Titova, L. (2016). Positive psychological interventions. In A. M. Wood & J. Johnson (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology (pp. 305-320). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2019). Character strengths and PERMA: Investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life. Web.

- The Arizona State University Observation Instrument Definition

- Behavior Management: To What Extent We Control It

- King of Masks: Themes

- "The Female Quixote" by Charlotte Lenox

- Generosity and Gratitude Relation

- Theoretical Mechanisms for Persuasive Technologies

- "Evaluation of a Mobile Crisis Program" by Scott R. L.

- Emotional Intelligence and Solution Formation

- Behavioral Treatment of Phobias

- Establishing Therapeutic Environment in Prisons to Address Recidivism in the USA

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, August 8). How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-developing-character-strengths-can-improve-well-being/

"How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being." IvyPanda , 8 Aug. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/how-developing-character-strengths-can-improve-well-being/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being'. 8 August.

IvyPanda . 2021. "How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being." August 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-developing-character-strengths-can-improve-well-being/.

1. IvyPanda . "How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being." August 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-developing-character-strengths-can-improve-well-being/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How Developing Character Strengths Can Improve Well-Being." August 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-developing-character-strengths-can-improve-well-being/.

Character Strengths: What Are They and Why They Matter?

by Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD

Ability to meet and overcome challenges in ways that maintain or promote well-being.

Determination

Flexibility, perseverance, self-confidence.

What are character strengths? What meaningful role does character play in child and adult development?

It is widely acknowledged that character –not beauty, high test scores, or wealth–account for life satisfaction and well-being. Derived from the field of positive psychology, the term character strengths has become synonymous with a group of 24 unique human characteristics developed by the VIA Institute on Character. Research suggests these attributes impact happiness, including our development of resilience and positive relationships.

How do children develop character strengths during their academic climb from kindergarten through high school? Educational goals of developing intelligence are well articulated and their outcomes can be measured. Until now, however, character strengths were less defined and not as measurable.

Martin Luther King Jr. understood the concept of character strengths long before they were as well-defined as they are today. At a speech at Morehouse College in 1948, he said, “We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character–that is the goal of true education.”

When I reflect on King’s statement, I think of my closest friends and the people I most respect. I am drawn to them by forces beyond intellect and external success. I admire their character strengths, the values they hold, and how they put their values into action. When we consider the role of families, schools, and communities in the broadest sense, it is important to understand how each of these stakeholders helps kids develop character strengths during childhood and adolescence that determine the kind of adults they will become.

This article defines character strengths and summarizes a framework for understanding them. As adults who model character to kids each and every day, it’s helpful to begin by taking inventory of our own character strengths!

Character Strengths Count Throughout Life

While researchers are not in total agreement, there has been effort in recent years to define and measure character strengths .

In their highly acclaimed academic textbook, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman attempt to define these inner virtues and strengths. Research suggests that “people who use these inner strengths every day are three times more likely to report having an excellent quality of life and six times more likely to be engaged at work.” You can read extended definitions of all these strengths at the nonprofit VIA Institute on Character , but simply put, they fall into the following six categories:

- Wisdom and Knowledge : Creativity, Curiosity, Judgment and Open-Mindedness, Love of Learning, Perspective

- Courage: Bravery, Perseverance, Honesty, Zest

- Humanity: Capacity to Love and Be Loved, Kindness, Social Intelligence

- Justice: Teamwork, Fairness, Leadership

- Temperance: Forgiveness and Mercy, Modesty and Humility, Prudence, Self-Regulation

- Transcendence: Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence, Gratitude, Hope, Humor, Religiousness and Spirituality

It’s important to note that this is one framework used to understand character strengths. I like the VIA Institute Model because it is easy to understand and backed by lots of empirical research. Some scholars argue that these character strengths are not new, but an adjunct to what we have learned by studying personality theory for decades. Every model has limitations and it’s best to consider them helpful guides rather than bibles for living a full and happy life.

The value of any kind of framework is in how it is understood and applied in the real world–in homes, classrooms, and out-of-school-time activities for children. That link from theory to practice is at the heart of our articles at Roots of Action .

Getting Started: Understanding Your Character Strengths

The survey for adults takes 30-40 minutes and produces a free report of your top five strengths. There is also a survey designed for youth ages 11-17 that takes 40-50 minutes. If you want more detailed reports of your 24 character strengths, fees vary from $10-$40.

A few years ago, my daughter and I took the survey. I opted for the free version which listed my top five strengths and what they mean. Mine were:

- Appreciation of beauty and excellence – You notice and appreciate beauty, excellence, and/or skilled performance in all domains of life, from nature to art to mathematics to science to everyday experience.

- Creativity, ingenuity, and originality – Thinking of new ways to do things is a crucial part of who you are. You are never content with doing something the conventional way if a better way is possible.

- Gratitude: You are aware of the good things that happen to you, and you never take them for granted. Your friends and family members know that you are a grateful person because you always take the time to express your thanks.

- Hope, optimism, and future-mindedness: You expect the best in the future, and you work to achieve it. You believe that the future is something that you can control.

- Industry, diligence, and perseverance: You work hard to finish what you start. No matter the project, you “get it out the door” in timely fashion. You do not get distracted when you work, and you take satisfaction in completing tasks.

Discussing Strengths of Character with Kids

My daughter chuckled at the results of my VIA Quiz, saying they fit me to a tee. “Anyone determined enough to get a Ph.D. in mid-life has to have a lot of ingenuity and perseverance!” she said.

Being in the middle of a job search, my daughter opted for the $40 report which she thought might be helpful in understanding her strengths as they related to a career choice. The 18-page report rank-ordered all of her strengths, not only giving her a top five but also information on how she could develop strengths that she didn’t use as much. It was a very helpful document.

My daughter’s top five strengths were completely different from mine, which was not surprising. Through our conversations, we learned a lot about each other, how we differ, and why we admire each other’s strengths. We agreed that developing character strengths mattered in life!

Want to learn about your own character strengths? Take the VIA Survey of Character . When you have finished, you’ll understand your own strengths and take the first step to learning how to foster character strengths in young people!

Next Steps: Fostering Personality Strengths in Families, Schools, and Communities

Understanding our own character strengths is an important first step to helping develop these strengths in our children:

- Learn how families can develop character by talking about and reinforcing the VIA character strengths from preschool through adolescence. If you hold regular family meetings with children ten or above, the results of the VIA survey make for wonderful conversation and learning!

- Learn why good teachers view character education as half their jobs and how one 4th grade teacher makes character strengths central to his core curriculum.

- Learn how communities support and encourage young people to be their best selves.

[This article was originally published May 6, 2011. It was updated with new information and research May 1, 2019.]

RELATED TOPICS:

Open-mindedness.

Published: May 1, 2019

Share Article:

About the author.

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD, is founder of Roots of Action and author of Tomorrow's Change Makers: Reclaiming the Power of Citizenship for a New Generation . A developmental psychologist and researcher, she writes for Psychology Today and Edutopia on positive youth development, K-12 education, and family-school-community partnerships. Website // @DrPriceMitchell // Facebook

Recent Articles

Creative Thinking Sparks Student Engagement & Discovery

Resourcefulness

Teach students to achieve goals.

Compass-Inspired

Best back-to-school articles for parents: 2023.

The Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues

This handbook also intends to provide an empirical theoretical framework that will assist positive psychology practitioners in developing practical applications for the field.

There are 6 classes of virtues that are made up of 24 character strengths:

- Wisdom and Knowledge

- Transcendence

Researchers approached the measurement of “good character” based on the strengths of authenticity, persistence, kindness, gratitude, hope, humor, and more.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Strengths Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients realize your unique potential and create a life that feels energized and authentic.

This Article Contains:

What makes us strong and virtuous, the csv handbook’s list, positive psychology & character strengths and virtues.

- What Strengths do Women Score Higher?

- What Strengths do Men Score Higher?

- What Can We Learn From Both

Development of Character Strengths in Children

- Character Strengths and Wellbeing in Adolescence

Videos on Character Strengths

A take-home message.

Cultures around the world have valued the study of human strength and virtue. Psychologists have a particular interest in it as they work to encourage individuals to develop these traits. While all cultures value human virtues, different cultures express or act on virtues in different ways based on differing societal values and norms.

Martin Seligman and his colleagues studied all major religions and philosophical traditions and found that the same six virtues (i.e. courage, humanity, justice, etc.) were shared in virtually all cultures across three millennia.

Since these virtues are considered too abstract to be studied scientifically, positive psychology practitioners focused their attention on the strengths of character created by virtues, and created tools for their measurement.

The main assessment instruments they used to measure those strengths were:

- Structured interviews

- Questionnaires

- Informant Reports

- Behavioral Experiments

- Observations

The main criteria for characters strengths that they came up with are that each trait should:

- Be stable across time and situations

- Be valued in its own right, even in the absence of other benefits

- Be recognized and valued in almost every culture, be considered non-controversial and independent of politics.

- Cultures provide role models that possess the trait so other people can recognize its worth.

- Parents aim to instil the trait or value in their children.

The Handbook delves into each of these six traits. We’ve summarized key points here.

1. Virtue of Wisdom and Knowledge

The more curious and creative we allow ourselves to become, the more we gain perspective and wisdom and will, in turn, love what we are learning. This is developing the virtue of wisdom and knowledge.

Strengths that accompany this virtue involve acquiring and using knowledge:

- Creativity (e.g. Albert Einstein’s creativity led him to acquire knowledge and wisdom about the universe)

- Open-mindedness

- Love of Learning

- Perspective and Wisdom (Fun fact: many studies have found that adults’ self-ratings of perspective and wisdom do not depend on age, which contrasts the popular idea that our wisdom increases with age).

2. Virtue of Courage

The braver and more persistent we become, the more our integrity will increase because we will reach a state of feeling vital, and this results in being more courageous in character.

Strengths that accompany this virtue involve accomplishing goals in the face of things that oppose it:

- Persistence

3. Virtue of Humanity

There is a reason why Oprah Winfrey is seen as a symbol of virtue for humanitarians: on every show, she approaches her guests with respect, appreciation, and interest (social intelligence), she practices kindness through her charity work, and she shows her love to her friends and family.

Strengths that accompany this virtue include caring and befriending others:

- Social intelligence

4. Virtue of Justice

Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of the Indian independence movement in British-ruled India. He led India to independence and helped created movements for civil rights and freedom by being an active citizen in nonviolent disobedience. His work has been applied worldwide for its universality.

Strengths that accompany this virtue include those that build a healthy and stable community:

- Being an active citizen who is socially responsible, loyal, and a team member.

5. Virtue of Temperance

Being forgiving, merciful, humble, prudent, and in control of our behaviors and instincts prevents us from being arrogant, selfish, or any other trait that is excessive or unbalanced.

Strengths that are included in this virtue are those that protect against excess:

- Forgiveness and mercy

- Humility and modesty

- Self-Regulation and Self-control

6. Virtue of Transcendence

The Dalai Lama is a transcendent being who speaks openly why he never loses hope in humanity’s potential. He also appreciates nature in its perfection and lives according to what he believes is his intended purpose.

Strengths that accompany this virtue include those that forge connections to the larger universe and provide meaning:

- Appreciation of beauty and excellence

- Humor and playfulness

- Spirituality , or a sense of purpose

Download 3 Free Strengths Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover and harness their unique strengths.

Download 3 Free Strengths Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Positive psychology practitioners can count on practical applications to help individuals and organizations identify their strengths and use them to increase and maintain their levels of wellbeing.

They also emphasize that these character strengths exist on a continuum; positive traits are regarded as individual differences that exist in degrees rather than all-or-nothing categories.

In fact, the handbook has an internal subtitle entitled “A Manual of the Sanities” because it is intended to do for psychological wellbeing what the DSM does for psychological disorders: to add systematic knowledge and ways to master new skills and topics.

Research shows that these human strengths can act as buffers against mental illness. For instance, being optimistic prevents one’s chances of becoming depressed. The absence of particular strengths may be an indication of psychopathology. Positive psychology therapists, counselors, coaches, and other psychological professions use these new methods and techniques to help build people’s strength and broaden their lives.

It should be noted that many researchers are advocating grouping these 24 traits into just four classes of strength (Intellectual, Social, Temperance, and Transcendence) or even three classes (excluding transcendence), as evidence has shown that these classes do an adequate job of capturing all 24 original traits.

Others caution that people occasionally use these traits to excess, which can become a liability to the person. For example, some people may use humor as a defense mechanism in order to avoid dealing with a tragedy.

Character strengths are the positive parts of our personality that make us feel authentic and engaged. They are a core and foundational part of who we are. Our strengths are linked to our development, wellbeing, and life satisfaction (Niemiec, 2013).

They influence how we think, act, feel, and represent what we value in ourselves and others. When we draw on our strengths, research shows we can have a more influential positive impact on others, improve our relationships, and enhance our wellbeing and happiness.

So, where can we begin? By recognizing our strengths, of course!

The VIA Survey is one validated tool that can help us discover our strengths, including those we tend to use and rely on the most (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Scientists found a common language of 24 character strengths that make up what is best about our personality. Everyone possesses all 24 character strengths to different degrees, so each person has a truly unique character strengths profile.

Each character strength falls under one of these six broad virtue categories, which are universal across cultures and nations:

- Wisdom : These strengths are useful in helping us learn and gather knowledge.

- Courage : These emotional strengths empower us to tackle adversity and how we tend to work through it.

- Humanity : These strengths come into play by helping us build and maintain positive, warm relationships with others.

- Justice : With these strengths, we relate to those around us in social or group situations.

- Temperance : Temperance strengths help us manage habits and protect against excess, including managing and overcoming vices.

- Transcendence : As a virtue, transcendence strengths connect us to the world around us in a meaningful way.

Knowing our strengths allows us to consciously use those that benefit us and develop those that we might find useful.

What Strengths Do Women Score Higher?

There’s an interest in identifying dominant character strengths in genders and how it is developed.

As Martin Seligman and his colleagues studied all major religions and philosophical traditions to find universal virtues, much of the research on gender and character strengths have been cross-cultural also.

In a study by Brdar, Anic, & Rijavec on gender differences and character strengths, women scored highest on the strengths of honesty, kindness, love, gratitude, and fairness.

Life satisfaction for women was predicted by zest, gratitude, hope, appreciation of beauty/excellence, and love for other women. A recent study by Mann showed that women tend to score higher on gratitude than men. Alex Linley and colleagues reported in a UK study that women not only scored higher in interpersonal strengths, such as love and kindness, but on social intelligence, too.

In a cross-cultural study in Spain by Ovejero and Cardenal, they found that femininity was positively correlated with love, social intelligence, appreciation of beauty, love of learning, forgiveness, spirituality, and creativity. The more masculine a man was, the more he correlated negatively with these character strengths.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

What Strengths Do Men Score Higher?

Brdar, Anic & Rijavac reported that men score highest on honesty, hope, humor, gratitude, and curiosity.

Their life satisfaction was predicted by creativity, perspective, fairness, and humor. Alex Linley and colleagues study showed that men scored higher than females on creativity.

Miljković and Rijavec’s study found sex differences in a sample of college students. Men not only scored higher in creativity, but also leadership, self-control, and zest. These findings are congruent with gender stereotypes, as the study by Ovejero and Cardenal in Spain showed that men did not equate typical masculine strengths with love, forgiveness, love of learning, and so on.

In a Croatian sample, Brdar and colleagues found that men viewed cognitive strengths as a greater predictor for life satisfaction. Men saw strengths such as teamwork, kindness , perspective, and courage to be a stronger connection to life satisfaction than other strengths. There is an important limitation to this sample population, as most of the participants were women.

What Can We Learn From Both?

While there are differences in character strengths between men and women, there are many that they share. Both genders saw gratitude, hope, and zest as being related to higher life satisfaction, as well as the tendency to live in accordance with the strengths that are valued in their particular culture.

Studies confirm that there is a duality between genders, but only when both genders identify strongly with gender stereotypes. It makes one wonder if men and women are inherently born with certain strengths, or if the cultural influence of certain traits prioritizes different traits based on gender norms.

Learn more about strengths and weaknesses tests here .

Park and Peterson’s study (2006) confirmed this theoretical speculation, concluding that these sophisticated character strengths usually require a degree of cognitive maturation that develops during adolescence. So although gratitude is associated with happiness in adolescents and adulthood, this is not the case in young children.

Park and Peterson’s study found that the association of gratitude with happiness starts at age seven.

“Gratitude is seen as a human strength that enhances one’s personal and relational wellbeing and is beneficial for society as a whole.”

Although most young children are not yet cognitively mature enough for sophisticated character strengths, there are many fundamental character strengths that are developed at a very early stage.

The strengths of love, zest, and hope are associated with happiness starting at a very young age. The strengths of love and hope are dependent on the infant and caregiver relationship. A secure attachment to the caregiver at infancy is more likely to result in psychological and social well adjustment throughout their lives.

The nurturing of a child plays a significant role in their development, and role modeling is an important way of teaching a child certain character strengths as they imitate behavior and can then embrace the strength as one of their own.

Most young children don’t have the cognitive maturity to display gratitude but have the ability to display love and hope. Therefore, gratitude must not be expected from a young child but must be taught.

Positive education programs have been developed to help children and adolescents focus on character strengths. There are certain character strengths in adolescents that have a clearer impact on psychological wellbeing. These strengths must be fostered to ensure life long fulfillment and satisfaction.

“Character strengths are influenced by family, community, societal, and other contextual factors. At least in theory, character strengths are malleable; they can be taught and acquired through practice.”

Gillham, et al.

17 Exercises To Discover & Unlock Strengths

Use these 17 Strength-Finding Exercises [PDF] to help others discover and leverage their unique strengths in life, promoting enhanced performance and flourishing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Character Strengths and Wellbeing in Adolescents

The majority of the research today on character strengths focuses on adults, despite the known importance of childhood and adolescence on character development.

Research into character strengths shows which promote positive development and prevent psychopathology.

Dahlsgaard, Park, and Peterson discovered that adolescents with higher levels of zest, hope, and leadership displayed lower levels of anxiety and depression in comparison to their peers with lower levels of these strengths. Other research findings suggested that adolescent character strengths contribute to wellbeing (Gillham, et al, 2011).

The research suggests that transcendence (eg. gratitude, meaning, and hope) predicts life satisfaction, demonstrating the importance of adolescents developing positive relationships, creating dreams, and finding a sense of purpose.

VIA Character Strengths Youth Survey

Parents, educators, and researchers have requested the VIA: institute on character strengths to develop a VIA survey that is especially aimed at youths. Take the VIA psychometric data – youth survey if you are between the ages of 10-17.

To finish off, here are some helpful videos for you to enjoy if you want to learn more about character strengths and virtues:

The measurement of character strengths and the different traits that go into making them have many applications, from life satisfaction to happiness and other wellbeing predictors. These measurement tools have been used to study how these strengths have been developed across genders and age groups.

What strengths do you possess? What implications can you see this research having in our world today? Can you see how it may apply to your own life?

Please share your thoughts in the comment section below.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Strengths Exercises for free .

- Bowlby, J.(1969). Attachment and Loss , (Vol. I). Attachment . Basic Books, New York.

- Dahlsgaard, K.K. (2005). Is virtue more than its own reward? Character strengths and their relation to well-being in a prospective, longitudinal study of middle school-aged adolescents (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) . University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia,PA.

- Gillham, J., Adams-Deutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., Coulter-Heindl, V., Linkins, M., Seligman, M. (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. The Journal of Positive Psychology , 6(1), 31-44.

- Jolly, M., & Academia. (2006). Positive Psychology: The Science of Human Strengths . Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/6442081/Positive_Psychology_The_Science_of_Human_Strengths

- Kochanska, G. (2001). Emotional development in children with different attachment histories: The first three years. Developmental Psychology 72, pp. 474–490.

- McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin , 127, 249−266.

- Niemiec, R. M. (2013). Mindfulness and character strengths . Hogrefe Publishing.

- Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006, a). Character strengths and happiness among young children: Content analysis of parental descriptions. Journal of Happiness Studie s, 7(3), 323-341.

- Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006, b). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth. Journal of adolescence , 29(6), 891-909.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues a handbook and classification .

- Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel . Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Tartakovsky, M. (2011). Measuring Your Character Strengths | World of Psychology . Retrieved from http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2011/01/05/measuring-your-character-strengths/

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Very interesting article – and I love that children are learning this information now. Hoping that while they learn more about their own strengths and weaknesses, they will not only develop their own character but be understanding and accepting of others as well.

Very useful article, i know only basic English. But your sentences are easily understandable. This way i can improve my English skills. Thank you all.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Type B Personality Advantages: Stress Less, Achieve More

Type B personalities, known for their relaxed, patient, and easygoing nature, offer unique advantages in both personal and professional contexts. There are myriad benefits to [...]

Jungian Psychology: Unraveling the Unconscious Mind

Alongside Sigmund Freud, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) is one of the most important innovators in the field of modern depth [...]

12 Jungian Archetypes: The Foundation of Personality

In the vast tapestry of human existence, woven with the threads of individual experiences and collective consciousness, lies a profound understanding of the human psyche. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Showcase Your Strengths in Your College Application Essays

Your admission essay is an adcom’s greatest insight into who you are as a person. It can also be a tool to showcase your high school accomplishments. So, how can you craft an essay that both conveys your personality and portrays your strengths—without coming off as arrogant? Here are four tips to guide you.

1. Paint a picture.

This is a phrase that English teachers have drilled into your head, but it’s true for your college essay and in all your written work. Painting a picture of your accomplishments through examples and rhetorical devices helps adcoms visualize the steps you’ve taken to get to where you are today and the person you are and strive to be.

How can you show rather than tell? There are many ways to express yourself through language, from personalized metaphors —actions, experiences, or objects that mirror and symbolize your journey—to rich, vivid details. This is especially true in your essay, but you can also employ these rhetorical devices and language throughout your application, such as in your extracurricular accomplishment descriptions.

For instance, if you’re a pianist, you might use imagery to describe the progression of your musical development, initially exploring playing one note at a time to learning how to play the music you play today. You could evoke specific sounds and melodies to illustrate this development.

2. Use action-oriented verbs.

Rather than relying on soft adjectives, use action verbs like “implemented,” “facilitated,” and so on. These types of words are much more powerful and demonstrate that you do and make things happen. They also emphasize your ownership of your achievements, signifying that these achievements don’t just happen to you: you made them happen.

For example, rather than saying that you were responsible for speaking on behalf of the student body as student council president, you might say, “Raised awareness of X issue and implemented a procedure for handling complaints.”

3. Offer examples and details.

Examples are an essential feature of your essay. They illustrate your accomplishments, provide context, and show adcoms how you’ve made an impact in concrete ways. You should also use numerical values and other details to quantify your accomplishments.

In this post on successful activity entries, students use details to summarize and portray their accomplishments. While this post concerns another section of your application, you can apply the same concepts to your essay.

Example: “Provided homework and study help to underprivileged kids. I studied with one girl until her Cs became As. I love being the “go-to” mentor.”

Here, the applicant shows the impact of her tutoring, rather than simply stating that she tutored. In doing so, she demonstrates the impact on both her and the students she tutored.

Example: “I have been studying piano and performing in recitals since kindergarten. I’m currently working on Beethoven’s Sonata No. 1 in F minor from Opus 2.”

This entry shows the progression of the applicant’s work by demonstrating how far she has come, exemplified by the challenging piece she’s currently playing.

These examples bring your experiences to life, so you’re not just listing achievements but also quantifying them and pointing to concrete ways in which they’ve affected you and others.

4. Tell a story.

Like any good story, your essay should have a narrative arc. Instead of a list of achievements, it should portray an experience that shaped you. No matter what topic you choose, you should be able to tell an account that captures your reader’s attention and has all the hallmarks of a compelling narrative.

For instance, if you’re a first-generation student, you might begin by describing a specific moment in your childhood when you realized that you would be the first member of your family to attend college and then narrate specific events along your journey, such as encouragement from your parents or teachers, difficulties you faced and how you overcame them, and how you finally reached this moment and are excited about the next chapter. This is much more effective than simply stating that you’re a first-generation student and listing the reasons why attending college is important to you.

If you can’t weave together a compelling story with the topic you’ve chosen, you may want to rethink it. Spend some time brainstorming to hone your topic and ensure that it is one that will both capture your audience and showcase your accomplishments.

Your Essay: A Reflection of You

Your essay is a concise glimpse into you as a person. While other areas of your application detail your accomplishments, grades, and extracurricular achievements, this is a place to showcase your qualities as a person. Still, your accomplishments are most likely integral to your personality. Keep these tips in mind as you craft an essay that both captures your character and your strengths as a candidate for admission.

Want help with your college essays to improve your admissions chances? Sign up for your free CollegeVine account and get access to our essay guides and courses. You can also get your essay peer-reviewed and improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

Need help with your college applications?

We’ve helped thousands of students write amazing college essays and successfully apply to college! Learn more about how our Applications Program can help your chances of admission.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Positive Psychology

Character Strengths

Character strengths are positive traits that are valued in and of themselves by nearly all cultures. A handbook of the 24 character strengths was created by Martin Seligman and Christopher Peterson, grouping them into six categories of virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity and love, justice, temperance, and transcendence.

According to Seligman, your top strengths also have to feel authentic and powerful to you; you have to delight in exercising them, and feel energized afterward. If one of your top strengths doesn’t fit those criteria, it’s not a ‘signature strength’. Below there are described the 24 character strengths by Seligman.

The VIA Institute on Character is a nonprofit formed in 2001 to study and promote character strengths. It offers a free survey that ranks your strengths, as well as reports, training, and speakers.

Once you’ve figured out your top strengths, positive psychologists often recommend figuring out your five ‘signature strengths.’ Growth and development examples often include using your top strengths, which also have to feel authentic and powerful to you; you have to delight in exercising them, and feel energized afterward. According to Seligman, your top strengths also have to feel authentic and powerful to you; you have to delight in exercising them, and feel energized afterward. If one of your top strengths doesn’t fit those criteria, it’s not a ‘signature strength

The 24 character strengths

Appreciation of beauty: You recognize beauty and excellence, and it awes you.

Citizenship: You work well in a group and respect your team members and leaders.

Curiosity: You are open to new experiences and thrive in situations of uncertainty. You aren’t easily bored.

Fairness: You have a strong sense of morality and believe in treating people equally, without regard for your feelings or prejudices.

Forgiveness: You forgive and give people second chances. You aren’t vengeful and don’t hold a grudge.

Gratitude: You’re thankful for other people and circumstances. You don’t take things for granted.

Humility: You’re modest and don’t seek attention. You don’t see your accomplishments as special.

Humor: You’re funny, and you enjoy making others laugh.

Ingenuity: You are creative and street smart. If you want something, you’ll find unique and original ways to get it.

Integrity: You are honest and transparent in word and in actions.

Judgment: You think critically and are open-minded to different perspectives. You can weigh facts objectively, without your feelings getting in the way.

Kindness: You enjoy making others happy, even if you don’t know them well.

Leadership: You successfully organize activities and treat group members equally.

Love of learning: You are the type of person who loves school, reading, and museums. You’re probably an expert in something, just because you love it.

Loving and being loved: You have strong relationships, where you can accept and give love.

Optimism: You have hope and expect good things, so you plan for a happy future.