- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

A brief introduction to the Chinese education system

This page was published over 5 years ago. Please be aware that due to the passage of time, the information provided on this page may be out of date or otherwise inaccurate, and any views or opinions expressed may no longer be relevant. Some technical elements such as audio-visual and interactive media may no longer work. For more detail, see how we deal with older content .

This content is associated with The Open University Childhood and Youth Studies qualification .

Structure of the Chinese education system

In China, education is divided into three categories: basic education, higher education, and adult education. By law, each child must have nine years of compulsory education from primary school (six years) to junior secondary education (three years).

Basic education

Basic education in China includes pre-school education (usually three years), primary education (six years, usually starting at the age of six) and secondary education (six years).

Secondary education has two routes: academic secondary education and specialized/vocational/technical secondary education. Academic secondary education consists of junior (three years) and senior middle schools (three years). Junior middle school graduates wishing to continue their education take a locally administered entrance exam, on the basis of which they will have the option of i) continuing in an academic senior middle school; or ii) entering a vocational middle school (or leaving school at this point) to receive two to four years of training. Senior middle school graduates wishing to go to universities must take National Higher Education Entrance Exam (Gao Kao). According to the Chinese Ministry of Education, in June 2015, 9.42 million students took the exam.

Higher education

Higher education is further divided into two categories: 1) universities that offer four-year or five-year undergraduate degrees to award academic degree qualifications; and 2) colleges that offer three-year diploma or certificate courses on both academic and vocational subjects. Postgraduate and doctoral programmes are only offered at universities.

Adult education

Adult education ranges from primary education to higher education. For example, adult primary education includes Workers’ Primary Schools, Peasants’ Primary Schools in an effort to raise literacy levels in remote areas; adult secondary education includes specialized secondary schools for adults; and adult higher education includes traditional radio/TV universities (now online), most of which offer certificates/diplomas but a few offer regular undergraduate degrees.

Term times and school hours

The academic year is divided into two terms for all the educational institutions: February to mid-July (six weeks of summer vacation) and September to mid/late-January (four weeks of winter vacation). There are no half-terms.

Most schools start in the early morning (about 7:30 am) to early evening (about 6 pm) with 2 hours lunch break. Many schools have evening self-study classes running from 7 pm-9 pm so students can finish their homework and prepare for endless tests. If schools do not run self-study evening classes, students still have to do their homework at home, usually up to 10 pm. On average, primary school pupils spend about seven to eight hours at school whilst a secondary school student spends about twelve to fourteen hours at school if including lunchtime and evening classes. Due to the fierce competitiveness to get into good universities, the pressure to do well for Gao Kao is intense. Many schools hold extra morning classes in science and math for three to four hours on Saturdays. If schools do not have Saturday morning classes, most parents would send their children to expensive cramming schools at weekends or organise one-to-one private tuition for their children over the weekend.

Find out more on Chinese education

Beginners’ Chinese: a taster course

Learn about Mandarin Chinese as a tool for communication and gain insights into Chinese society and culture. This free course, Beginners’ Chinese: a taster course, provides a brief introduction to the Chinese language, its scripts and sounds, and how words are formed. You will hear short conversations where people greet each other and introduce ...

12 famous Confucius quotes on education and learning

What's your favourite Confucius quote on education and learning? Look at these examples...

Getting started with Chinese 1

Have you always wanted to learn how to speak Mandarin Chinese? Are you fascinated by the sound, the script and its ancient civilisation? If so, this introduction will get you started on the essentials of reading, writing, speaking and listening in Chinese through a variety of online activities. A perfect introduction for absolute ...

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 14 July 2015

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'students working at their desks in a Chinese school' - Copyright: Monkey Business Images | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'university in china' - David.78 under CC-BY-NC-ND licence under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Getting started with Chinese 1' - Copyright: Toa55/iStock / Getty Images Plus

- Image 'Beginners’ Chinese: a taster course' - Copyright free

- Image 'A brief introduction to the Chinese education system' - Copyright: Monkey Business Images | Dreamstime.com

- Image '12 famous Confucius quotes on education and learning' - Copyright free: MorgueFile

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Northeast Plain

- The Changbai Mountains

- The North China Plain

- The Loess Plateau

- The Shandong Hills

- The Qin Mountains

- The Sichuan Basin

- The southeastern mountains

- Plains of the middle and lower Yangtze

- The Nan Mountains

- The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau

- The Plateau of Tibet

- The Tarim Basin

- The Junggar Basin

- The Tien Shan

- The air masses

- Temperature

- Precipitation

- Animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Sino-Tibetan

- Other languages

- Rural areas

- Urban areas

- Population growth

- Population distribution

- Internal migration

- The role of the government

- Economic policies

- Farming and livestock

- Forestry and fishing

- Hydroelectric potential

- Energy production

- Manufacturing

- Labor and taxation

- Road networks

- Port facilities and shipping

- Posts and telecommunications

- Parallel structure

- Constitutional framework

- Role of the CCP

- Administration

- Health and welfare

- Cultural milieu

- Visual arts

- Performing arts

- Cultural institutions

- Daily life, sports, and recreation

- Media and publishing

- Archaeology in China

- Early humans

- Climate and environment

- Food production

- Incipient Neolithic

- 6th millennium bce

- 5th millennium bce

- 4th and 3rd millennia bce

- Regional cultures of the Late Neolithic

- Religious beliefs and social organization

- The advent of bronze casting

- Royal burials

- The chariot

- Late Shang divination and religion

- State and society

- Zhou and Shang

- The Zhou feudal system

- The decline of feudalism

- Urbanization and assimilation

- The rise of monarchy

- Economic development

- Cultural change

- The Qin state

- Struggle for power

- Prelude to the Han

- The imperial succession

- From Wudi to Yuandi

- From Chengdi to Wang Mang

- Dong (Eastern) Han

- The civil service

- Provincial government

- The armed forces

- The practice of government

- Relations with other peoples

- Cultural developments

- Sanguo (Three Kingdoms; 220–280 ce )

- The Xi (Western) Jin (265–316/317 ce )

- The Dong (Eastern) Jin (317–420) and later dynasties in the south (420–589)

- The Shiliuguo (Sixteen Kingdoms) in the north (303–439)

- Confucianism and philosophical Daoism

- Wendi’s institutional reforms

- Integration of the south

- Foreign affairs under Yangdi

- Administration of the state

- Fiscal and legal system

- The “era of good government”

- Rise of the empress Wuhou

- Prosperity and progress

- Military reorganization

- Provincial separatism

- The struggle for central authority

- The influence of Buddhism

- Trends in the arts

- Decline of the aristocracy

- Population movements

- Growth of the economy

- The Wudai (Five Dynasties)

- The Shiguo (Ten Kingdoms)

- Unification

- Consolidation

- Decline and fall

- Survival and consolidation

- Relations with the Juchen

- The court’s relations with the bureaucracy

- The chief councillors

- The bureaucratic style

- The clerical staff

- The rise of neo-Confucianism

- Internal solidarity during the decline of the Nan Song

- Song culture

- Invasion of the Jin state

- Invasion of the Song state

- Early Mongol rule

- Changes under Kublai Khan and his successors

- Foreign religions

- Confucianism

- Yuan China and the West

- The end of Mongol rule

- The dynasty’s founder

- The dynastic succession

- Local government

- Central government

- Later innovations

- Foreign relations

- Agriculture

- Philosophy and religion

- Literature and scholarship

- The rise of the Manchu

- Political institutions

- Social organization

- Trends in the early Qing

- The first Opium War and its aftermath

- The anti-foreign movement and the second Opium War (Arrow War)

- The Taiping Rebellion

- The Nian Rebellion

- Muslim rebellions

- Effects of the rebellions

- Foreign relations in the 1860s

- Industrialization for “self-strengthening”

- East Turkistan

- Tibet and Nepal

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Japan and the Ryukyu Islands

- Korea and the Sino-Japanese War

- The Hundred Days of Reform of 1898

- The Boxer Rebellion

- Sun Yat-sen and the United League

- Constitutional movements after 1905

- The Chinese Revolution (1911–12)

- Early power struggles

- Japanese gains

- Yuan’s attempts to become emperor

- Conflict over entry into the war

- Formation of a rival southern government

- Wartime changes

- An intellectual revolution

- Riots and protests

- The Nationalist Party

- The Chinese Communist Party

- Communist-Nationalist cooperation

- Militarism in China

- The foreign presence

- Reorganization of the KMT

- Clashes with foreigners

- KMT opposition to radicals

- The Northern Expedition

- Expulsion of communists from the KMT

- Japanese aggression

- War between Nationalists and communists

- The United Front against Japan

- Phase two: stalemate and stagnation

- Renewed communist-Nationalist conflict

- U.S. aid to China

- Conflicts within the international alliance

- Phase three: approaching crisis (1944–45)

- Nationalist deterioration

- Communist growth

- Efforts to prevent civil war

- Attempts to end the war

- Resumption of fighting

- A land revolution

- The decisive year, 1948

- Communist victory

- Reconstruction and consolidation, 1949–52

- Rural collectivization

- Urban socialist changes

- Political developments

- Foreign policy

- New directions in national policy, 1958–61

- Readjustment and reaction, 1961–65

- Attacks on cultural figures

- Attacks on party members

- Seizure of power

- The end of the radical period

- Social changes

- Struggle for the premiership

- Consequences of the Cultural Revolution

- Readjustment and recovery

- Economic policy changes

- Educational and cultural policy changes

- COVID-19 outbreak

- Allegations of human rights abuses

- International relations

- Relations with Taiwan

- Leaders of the People’s Republic of China since 1949

- What are the major ethnic groups in China?

- Who was Mao Zedong?

- What is Maoism?

- How has China changed since Mao Zedong’s death?

- What is Mao Zedong's legacy?

Education of China

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Geographic Kids - 30 cool facts about China!

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - China

- China - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- China - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The educational system in China is a major vehicle for both inculcating values in and teaching needed skills to its people. Traditional Chinese culture attached great importance to education as a means of enhancing a person’s worth and career. In the early 1950s the Chinese communists worked hard to increase the country’s rate of literacy, an effort that won them considerable support from the population. By the end of that decade, however, the government could no longer provide jobs adequate to meet the expectations of those who had acquired some formal schooling. Other pressing priorities squeezed educational budgets, and the anti-intellectualism inherent in the more-radical mass campaign periods affected the status and quality of the educational effort. These conflicting pressures made educational policy a sensitive barometer of larger political trends and priorities. The shift to rapid and pragmatic economic development as the overriding national goal in the late 1970s quickly affected China’s educational system.

Recent News

The Chinese educational structure provides for six years of primary school , three years each of lower secondary school and upper secondary school, and four years in the standard university curriculum. All urban schools are financed by the state, while rural schools depend more heavily on their own financial resources. Official policy stresses scholastic achievement, with particular emphasis on the natural sciences. A significant effort is made to enhance vocational training opportunities for students who do not attend a university . The quality of education available in the cities generally has been higher than that in the countryside, although considerable effort has been made to increase enrollment in rural areas at all education levels.

The traditional trend in Chinese education was toward fewer students and higher scholastic standards, resulting in a steeply hierarchical educational system. Greater enrollment at all levels, particularly outside the cities, is gradually reversing that trend. Primary-school enrollment is now virtually universal, and nearly all of those students receive some secondary education; about one-third of lower-secondary graduates enroll in upper-secondary schools. The number of university students is increasing rapidly, though it still constitutes only a small fraction of those receiving primary education . For the overwhelming majority of students, admission to a university since 1977 has been based on competitive nationwide examinations, and attendance at a university is usually paid for by the government. In return, a university student has had to accept the job provided by the state upon graduation. A growing number of university students are receiving training abroad, especially at the postgraduate level.

The system that developed in the 1950s of setting up “key” urban schools that were given the best teachers, equipment, and students was reestablished in the late 1970s. The inherently elitist values of such a system put enormous pressure on secondary-school administrators to improve the rate at which their graduates passed tests for admission into universities. In addition, dozens of elite private schools have been established since the early 1990s in China’s major cities.

Six universities, all administered directly by the Ministry of Education in Beijing , are the flagships of the Chinese higher educational system. Three are located in Beijing: Peking University (Beijing Daxue), the leading nontechnical institution; Tsinghua (Qinghua) University, which is oriented primarily toward science and engineering; and People’s University of China, the only one of the six founded after 1949. The three outside Beijing are Nankai University in Tianjin , which is especially strong in the social sciences; Fudan University, a comprehensive institution in Shanghai ; and Sun Yat-sen (Zhongshan) University in Guangzhou (Canton), the principal university of South China. In addition, every province has a key provincial university, and there are hundreds of other technical and comprehensive higher educational institutions in locations around the country. The University of Hong Kong (founded 1911) is the oldest school in Hong Kong.

The damage done to China’s human capital by the ravages of the Great Leap Forward and, especially, by the Cultural Revolution was so great that it took years to make up the loss. After the 1970s, however, China’s educational system increasingly trained individuals in technical skills so that they could fulfill the needs of the advanced, modern sector of the economy. The social sciences and humanities also receive more attention than in earlier years, but the base in those disciplines is relatively weak—many leaders still view them with suspicion—and the resources devoted to them are thin.

Cultural life

China is one of the great cradles of world civilization, and its culture is remarkable for its duration, diversity , and influence on other cultures , especially those of its East Asian neighbors. Following is a survey of Chinese culture; in-depth discussions of specific cultural aspects are found in the article Chinese literature and in the sections on Chinese visual arts , music , and dance and theater of the article arts, East Asian .

- Society ›

Education & Science

Education in China - statistics & facts

China's educational system, large regional disparities, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Share of GDP spent on public education in China 2010-2022

Number of students at high schools in China 2012-2022

Number of college and university graduates in China 2013-2023

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Education Level & Skills

Adult literacy in China 1982-2020

Enrollment rate in tertiary education in China 1990-2023

Leading destinations for Chinese students studying abroad 2015 and 2022

Further recommended statistics

General overview.

- Premium Statistic Education Index - comparison of selected countries 2022

- Basic Statistic Adult literacy in China 1982-2020

- Basic Statistic Illiteracy rate in China 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Enrollment rate in senior secondary education in China 1990-2023

- Premium Statistic Enrollment rate in tertiary education in China 1990-2023

- Basic Statistic Leading universities Asia 2024

Education Index - comparison of selected countries 2022

Education index including inequality* of selected countries in 2022

Adult literacy rate in China from 1982 to 2020

Illiteracy rate in China 2022, by region

Illiteracy rate in China in 2022, by region

Enrollment rate in senior secondary education in China 1990-2023

Gross enrollment ratio in senior secondary education in China from 1990 to 2023

Gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education in China from 1990 to 2023

Leading universities Asia 2024

Leading universities as ranked by Times Higher Education in Asia in 2024

Education expenditure

- Premium Statistic Public expenditure on education in China 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Share of GDP spent on public education in China 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Public education spending per student in China 2022, by level of education

- Premium Statistic Per capita spending of urban households in China on education & leisure 1990-2023

- Premium Statistic Per capita expenditure of private households in China on education 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Per capita spending of households in China on education & leisure 2000-2023

Public expenditure on education in China 2013-2023

Public expenditure on education in China from 2013 to 2023 (in billion yuan)

Public expenditure on education as a share of the gross domestic product (GDP) in China from 2010 to 2022

Public education spending per student in China 2022, by level of education

Public education spending per student in China in 2022, by level of education (in yuan)

Per capita spending of urban households in China on education & leisure 1990-2023

Annual per capita expenditure of private urban households in China on education, culture, and recreation from 1990 to 2023 (in yuan)

Per capita expenditure of private households in China on education 2022, by region

Per capita expenditure of private urban households in China on education, culture and recreation in 2022, by region (in yuan)

Per capita spending of households in China on education & leisure 2000-2023

Annual per capita expenditure of households in China on education, culture, and recreation from 2000 to 2023 (in yuan)

Educational infrastructure

- Premium Statistic Number of pre-schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of elementary schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of elementary schools in China 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Number of secondary vocational schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of high schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of colleges and universities in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of colleges and universities in China 2022, by region

Number of pre-schools in China 2012-2022

Number of pre-schools in China between 2012 and 2022

Number of elementary schools in China 2012-2022

Number of elementary schools in China between 2012 and 2022

Number of elementary schools in China 2022, by region

Number of elementary schools in China in 2022, by region

Number of secondary vocational schools in China 2012-2022

Number of secondary vocational schools in China between 2012 and 2022

Number of high schools in China 2012-2022

Number of high schools in China between 2012 and 2022

Number of colleges and universities in China 2012-2022

Number of public colleges and universities in China between 2012 and 2022

Number of colleges and universities in China 2022, by region

Number of public colleges and universities in China in 2022, by region

Student situation

- Premium Statistic Number of students at elementary schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Share of students repeating a year at elementary school in China 2018

- Premium Statistic Number of students at high schools in China 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of students at colleges and universities in China 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Undergraduate students enrolled at universities in China 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Number of college and university graduates in China 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of college and university graduates in China 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Monthly salary of university graduates in China 2012-2022

Number of students at elementary schools in China 2012-2022

Number of students at elementary schools in China between 2012 and 2022 (in millions)

Share of students repeating a year at elementary school in China 2018

Share of students repeating a year at elementary school in China between 2008 and 2018

Number of students at high schools in China between 2012 and 2022 (in millions)

Number of students at colleges and universities in China 2013-2023

Number of undergraduate students enrolled at public colleges and universities in China from 2013 to 2023 (in millions)

Undergraduate students enrolled at universities in China 2022, by region

Number of undergraduate students enrolled at public colleges and universities in China in 2022, by region (in 1,000s)

Number of graduates from public colleges and universities in China between 2013 and 2023 (in 1,000s)

Number of college and university graduates in China 2022, by region

Number of graduates from public colleges and universities in China in 2022, by region (in 1,000s)

Monthly salary of university graduates in China 2012-2022

Monthly salary of college and university graduates in China from 2012 to 2022 (in yuan)

Foreign students in China

- Premium Statistic Total number of foreign students studying in China 2014-2018

- Premium Statistic Number of foreign students studying in China 2018, by country of origin

- Premium Statistic Most popular regions among foreign students in China 2018

- Premium Statistic Number of foreign students studying in China 2009-2018, by source of funding

- Premium Statistic Number of students from the United States studying in China 2011/12-2021/22

Total number of foreign students studying in China 2014-2018

Total number of foreign students studying in China from 2014 to 2018

Number of foreign students studying in China 2018, by country of origin

Number of foreign students studying in China in 2018, by selected country of origin

Most popular regions among foreign students in China 2018

Most popular regions among foreign students in China in 2018

Number of foreign students studying in China 2009-2018, by source of funding

Number of foreign students studying in China from 2009 to 2018, by source of funding

Number of students from the United States studying in China 2011/12-2021/22

Number of college and university students from the United States studying in China from academic year 2011/12 to 2021/22

Studying abroad

- Premium Statistic Number of Chinese students studying abroad 2010-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of Chinese students in the U.S. 2012/13-2022/23

- Premium Statistic Leading destinations for Chinese students studying abroad 2015 and 2022

- Premium Statistic Motivations of Chinese students to study abroad 2015-2024

- Premium Statistic Chinese student's intention to study abroad under COVID-19 2023

Number of Chinese students studying abroad 2010-2022

Number of students from China going abroad for study from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of Chinese students in the U.S. 2012/13-2022/23

Number of college and university students from China in the United States from academic year 2012/13 to 2022/23

Chinese students' preferred destinations for studying overseas in 2015 and 2022

Motivations of Chinese students to study abroad 2015-2024

Major reasons for Chinese student to study overseas in 2015 and 2024

Chinese student's intention to study abroad under COVID-19 2023

Influence of coronavirus on Chinese student's plan to study overseas in 2023

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Workplace learning and development

- Private education in South Korea

- Labor Shortage: Workers with a higher education

- Tertiary education in the Asia-Pacific region

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

Education in China: An Introduction

- Open Access

- First Online: 02 January 2024

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Zhuolin Feng 4 &

- Xintong Jia 4

7295 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Chinese education has undergone tremendous transformation along with its socioeconomic reform in the past four decades. Education is no exception; it continues to change along with an increasingly complex and diversified world. This book provides a comprehensive overview and profound insights of education in China, to encourage further discussions on the issues and challenges confronting Chinese education and the world and to promote international understanding. The first chapter presents an overview of education in China over the past four decades and provides contextual information and analysis for the following 11 chapters. It reviews educational goals based on China’s Five-Year Plans and introduces the Chinese education system and structure. It explores the development of education and research in China, and reflects developmental trends based on statistical analysis.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Education System of Chile

The Chilean Education System

The Modernization of Education in China Over the Past Century

- Educational development

- Education system

- Educational scale

- Education resources

- Scientific research

1 An Overview of the Chinese Education System

Education in China has undergone tremendous transformation along with its socioeconomic reform in the past four decades. This chapter provides a general introduction on education development and systems in China. The analysis in this section focuses on educational goals in the twenty-first century since the beginning of 2000s, as well as educational development and progress since the reform and opening-up in 1978.

1.1 Evolving Educational Goals in the Past Two Decades

The analysis of educational goals is based on the policy documents of the Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China (hereafter the Five-Year Plan) endorsed by the National People’s Congress. The Five-Year Plans are formulated every five years and establish the main policy directions for further reform and development in the next five years. This series of plans set development goals for education, which reflect the educational conditions in China over time. By analyzing the goals during the past two decades, the progress and advancement of government’s efforts on education can be summarized and more clearly understood.

1.1.1 The 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005)

Speeding up Education Development. The 10th Five-Year Plan was endorsed by the ninth National People’s Congress in 2001 (National People’s Congress, 2001 ). It set China’s development goals from 2001 to 2005 and proposed to speed up development.

To Develop All Types of Education at All Levels. The Plan put forward to promote well-rounded education ( suzhi education) Footnote 1 and the holistic development of students on moral, intellectual, physical, and aesthetic aspects. It prioritized the development of basic education, consolidated educational achievements in areas where nine-year compulsory education had been basically universal, and focused on developing compulsory education in economically disadvantaged areas in western China and areas with concentrations of ethnic minorities. The Plan pointed out the need to expand upper secondary education. It also proposed to implement Project 211 and strengthen a number of leading universities and disciplines in higher education. It also pushed the development of vocational education and training, early childhood education and distance learning in the Chinese context. ( ibid ).

To Further Reform the Education System. The Plan proposed to speed up the reform of schooling systems, to encourage, support, and standardize non-state actors to run schools in various forms, and establish an operating model for developing both public and private education sectors concurrently under the government’s guidance. The Plan intended to deepen the reform of education management system, guarantee decision-making powers of higher education institutions (hereafter HEIs) in accordance with the law, and construct an educational system that bridges vocational and traditional education. The Plan also encouraged increased education investment, strengthened mechanism to ensure funding to the compulsory education sector, and enhanced personnel and employment system for university graduates. ( ibid ).

1.1.2 The 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010)

Prioritizing Education Development. The 11th Five-Year Plan was endorsed by the 10th National People’s Congress in 2006 (National People’s Congress, 2006 ). It set China’s development goals from 2006 to 2010 and proposed to prioritize education development.

To Reinforce and Make Compulsory Education for All. The Plan put forward to reinforce the importance of compulsory education in rural areas, reduce the dropout rate of rural students, and promote the balanced development of compulsory education in urban and rural areas. ( ibid ).

To Develop Vocational Education and Training. The Plan proposed to further develop secondary vocational education, promote various vocational skills training projects and reform the teaching methods of vocational education. ( ibid ).

To Strengthen Higher Education Quality. The Plan encouraged improving the quality of higher education, optimizing the structure and enhancing the popularization of higher education. It proposed to strengthen the development of leading universities and key disciplines. Adult education was also emphasized. ( ibid ).

To Increase Educational Investment. The Plan specified a goal of gradually raising the percentage of government expenditure on education represented in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) to 4%. It aimed to promote educational equality and it proposed to allocate more public educational resources to rural areas, the central and western regions, poor areas and minority areas. It also pointed out the need for further developing student loans system, improving the subsidy system for students at all levels of schools, and the student aid system for economically disadvantaged students. ( ibid ).

To Further Reform the Education System. The Plan emphasized the need to make clear the responsibilities of government at all levels to provide public education, form a diversified system of educational investment and establish a strict publicity system for educational charges. It put forward creating a teaching system that adapted the requirements of well-rounded education, reforming the examination and enrollment systems, and promoting the reform of teaching, curriculum, and evaluation. It also proposed to reform education management system and establish a system that had clear regulations of responsibilities and guaranteed the decision-making powers of schools. ( ibid ).

1.1.3 The 12th Five-Year Plan (2011–2015)

Further Accelerating Education Reform. The 12th Five-Year Plan was endorsed by the 11th National People’s Congress in 2011(National People’s Congress, 2011 ). It set China’s development goals from 2011 to 2015 and proposed to further accelerate education reform.

To Develop All Types of Education at All Levels. The Plan set the goal of actively developing preschool education and raising total enrollment for children receiving one-year preschool education to 85%. It emphasized reinforcing the achievement of the popularization of compulsory education. It also sought to popularize upper secondary education during the Five-Year period, vigorously develop vocational education and emphasize rural education. It was vital to improve the quality of higher education while speeding up the construction of world-class universities, national top universities, and key disciplines. It was also important to support education for minority nationalities and speed up the development of special education and continuing education. ( ibid ).

To Enhance Education Equality. The Plan pointed out the push to distribute educational resources equally, narrow the gap of educational development between regions, and promote a balanced development of compulsory education. It emphasized education development in rural, remote or poor areas and minority areas. ( ibid ).

To Promote Well-Rounded Education. In order to promote well-rounded education, the Plan put forward to reform the content, teaching methods and assessment system of education, and reinforce the holistic development of students on moral, intellectual, physical, and aesthetic aspects. It sought to widely administer Academic Proficiency Test and Comprehensive Student Assessment in upper secondary education. In higher education, the Plan focused on carrying out projects related to the improvement of teaching quality, instructional reform, and the creation of an effective evaluation system. ( ibid ).

To Further Reform the Education System. The Plan set the goal of reforming the examination system and enrollment method, and gradually forming an effective system including classified exams, comprehensive quality assessment and diversified admission standards. The decision-making powers of schools were guaranteed and expanded, and non-state actors were encouraged to run schools. The Plan also claimed to follow globalization trends, strengthen international cooperation, and underscore high-quality educational resources. ( ibid ).

1.1.4 The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020)

Promoting the Modernization of Education. The 13th Five-Year Plan was endorsed by the 12th National People’s Congress in 2016 (National People’s Congress, 2016 ). It set China’s development goals from 2016 to 2020 and proposed to promote the modernization of education.

To Promote the Balanced Development of Basic Public Education. The Plan proposed to establish a unified urban and rural funding mechanism for compulsory education, take appropriate measures to ensure that state-run schools that provide compulsory education comply with educational standards, and work to raise the completion rate of compulsory education to 95%. It was important to improve the quality of teachers with emphasis on those teachers in rural areas and improve the teaching environment in rural schools. The Plan envisioned a more accessible preschool education system by proposing the targets of opening kindergartens to all children and raising the gross enrollment for children receiving three-year preschool education to 85%. It specified the goal of raising the gross enrollment of upper secondary education to over 90%. The Plan also encouraged increased availability of special needs education for groups with disabilities and promoted the development of education for ethnic minority students. ( ibid ).

To Integrate Vocational Education and Industry. The Plan aimed to improve the modern vocational education system and give momentum to training models for applied expertise and technical skills, which allow for the involvement of industry and vocational education as well as increased cooperation between schools and enterprises. It also emphasized the mutual recognition and vertical mobility between vocational education and regular education. ( ibid ).

To Train Innovators in University. The Plan attached importance to the system for ensuring the quality of higher education. It intended to manage higher education based on classifications and carry out the comprehensive reform of institutions of higher learning, implement an educational system using different methods to train academic talents and applied talents whilst combining general knowledge and major-specific knowledge. It aimed to invigorate higher education in the central and western regions. The Plan sought to ensure that all universities improve their capacity for innovation and adopt a coordinated approach to developing world-class universities and disciplines. ( ibid ).

To Build a Learning Society. The Plan emphasized developing continuing education and it envisioned a system for lifelong learning and training that was available to all members of society. The open sharing of learning resources and the development of senior citizen education were also encouraged. ( ibid ).

To Enhance the Vitality of the Reform of Education. The Plan emphasized furthering reform examination and enrollment systems as well as instructional method. It also put forth efforts to reform the professional title system for elementary and secondary school teachers nationwide and promote close integration of modern information technology with education and teaching. The decision-making powers of schools were expanded, and non-state actors and investors were encouraged to provide a diverse range of educational services. ( ibid ).

1.1.5 The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) and Vision 2035

Reinforcing a High-Quality Education System. The 14th Five-Year Plan and Vision 2035 was endorsed by the 13th National People’s Congress in 2021 (National People’s Congress, 2021 ). It sets China’s development goals from 2021 to 2025 and puts forward China’s long-term development plan towards 2035. In education sector, it proposes to reinforce a high-quality education system.

To Promote the Equality of Basic Public Education. The most current Plan aims to consolidate the achievement of balanced development of compulsory education, promote the further development of balanced compulsory education, and close the urban–rural divide. It seeks to strengthen the ranks of teachers and improve the quality of teaching staff in rural schools. In upper secondary education, it specifies the target of raising the gross enrollment ratio to over 92%. The Plan also sets the goals of guaranteeing preschool education be more inclusive and requiring special education and specialized education be more accessible. It requires the gross enrollment of preschool education to be raised to over 90%. ( ibid ).

To Enhance the Adaptability of Vocational Education . It is important to highlight the characteristics of vocational education and train substantial talents with technical and professional skills. The Plan seeks to reform the schooling mode of vocational education and give impetus to the involvement of industry and vocational education as well as cooperation between schools and enterprises. It also emphasizes the link between vocational education and regular education. ( ibid ).

To Improve the Quality of Higher Education . The Plan puts forward managing higher education based on classifications, carrying out comprehensive reform of institutions of higher learning, and enhancing the gross enrollment ratio to 60%. It encourages the adoption of a classified approach to developing world-class universities and disciplines, and it supports the development of leading research universities. It also points out the importance of reforming the talent training system for basic disciplines and expanding the scale of graduates with professional degrees. ( ibid ).

To Improve the Quality of Teaching Staff. The Plan intends to establish a modern system of high-performing teaching staff, and places emphasis on constructing normal education bases, developing public-funded education for normal university students, and deepening the comprehensive reform of the management of teachers in elementary schools, secondary schools, and kindergartens. ( ibid ).

To Further Reform Education. The Plan aims to improve the systems and mechanisms of educational assessment and develop well-rounded education. It requires education to be covered in public welfare, and it points out to raise the spending on education and increase the efficiency of the use of educational spending. It is important to expand the decision-making powers of schools and reinforce the comprehensive reform of examination and enrollment systems. It also recommends supporting and regulating the development of non-state education and promote the cooperation with leading schools of other countries. Moreover, the Plan intends to exploit the advantages of online education, improve the system of lifelong learning and build a learning society. ( ibid ).

1.1.6 Developmental Trends of Educational Goals

Since 2001, China has experienced a period of rapid development. These five Five-Year Plans issued during this period have proposed educational goals based on China’s conditions at that time and have been leading the development of education in China. The Plans have been guiding China to improve educational quality and promote educational equity. During the past 20 years, the educational goals have been increasingly detailed. Specific goals have been put forward for all types of education and at all levels. Making education for all and promoting educational reform have become a priority. Above all, the quality of education has been emphasized all the time. The fundamental criterion for measuring the quality of education is promoting the all-round development of individuals and meeting the needs of society (The State Council, 2010 ). The Five-Year Plans put forward specific reform measures for all types of education at all levels to guarantee the development of well-rounded education and promote the all-round development of students on moral, intellectual, physical, and aesthetic aspects. In the background, enrollment ratios of schools at all levels have been consistently rising; the emphasis on quality reflects the transformation of China’s main target from scale expansion to deep development. In order to implement a comprehensive economic and social development strategy for the country, China has relied heavily on science and education, emphasized on talent development, and determined to drive development through innovation. Therefore, developing well-rounded education and continuously improving the quality of education, have been and will be the long-term development goals (Table 1 ).

1.2 The Education System

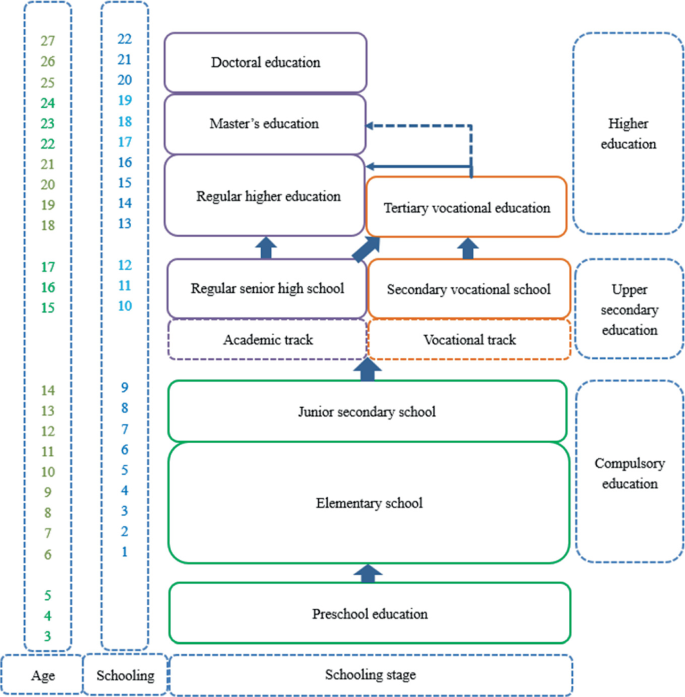

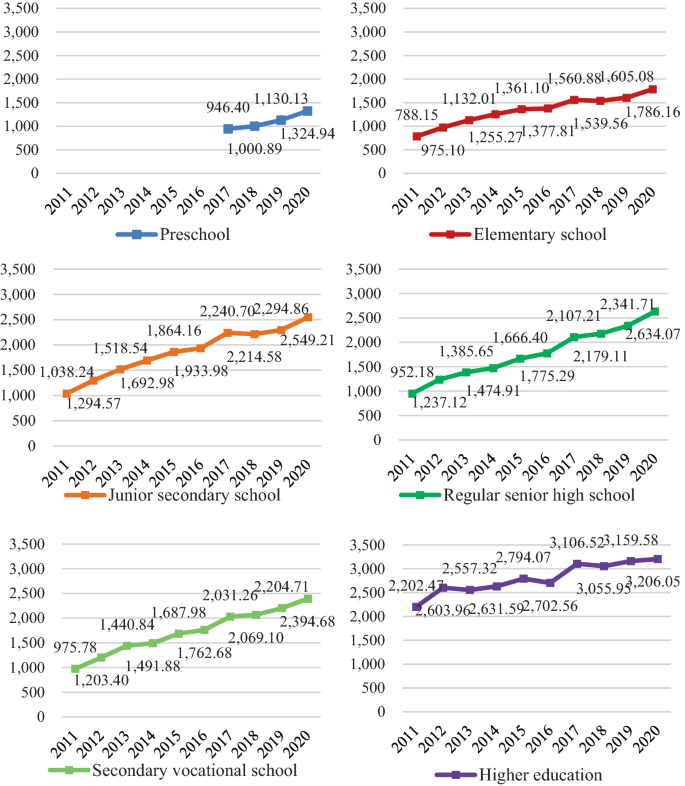

China’s education system covers preschool education, compulsory education, upper secondary education, and higher education (Fig. 1 ). Compulsory education includes elementary education and lower secondary education; higher education includes undergraduate education and graduate education.

The education system of China. Source Adapted from OECD ( 2016 )

1.2.1 Preschool Education

In China, children usually enroll in preschool at the age of two or three and leave preschool at the age of six. Preschool education is not compulsory education. However, the government takes a proactive role in promoting preschool accessibility. Public preschool and private preschool are both important in China. In 2021, 48.11% of preschool students were in private preschools (Ministry of education [MOE], 2022 ).

1.2.2 Compulsory Education

China adopts a system of nine-year compulsory education, which shall be received by all school-age children and adolescents. It generally includes six years of elementary education and three years of lower secondary education. However, there is some variation between regions with a small number of them having a “5 + 4” rather than a “6 + 3” structure. In public schools, compulsory education is publicly funded and is implemented uniformly by the State; no tuition or miscellaneous fees are charged, and the State shall establish a guaranteed mechanism for operating funds for compulsory education. Elementary education and lower secondary education are also provided by private schools, while they are not free of charge. In 2021, 10.60% of compulsory education students were in private schools (MOE, 2022 ). In compulsory education, curricula and standards are set by MOE and then implemented nationwide by provincial and municipal governments. Article Three of Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that well-rounded education shall be carried out to improve the quality of education and enable children and adolescents to achieve all-round development—morally, intellectually, and physically—so as to lay the foundation for cultivating well-educated and self-disciplined workforce with high ideals and moral integrity (National People’s Congress, 2018a ).

1.2.3 Upper Secondary Education

After compulsory education, students can choose whether to continue to upper secondary education. Upper secondary education is three years in duration and includes two types of schools: regular senior high schools and secondary vocational schools. Regular senior high school represents academic track, while secondary vocational school represents vocational track. Footnote 2 Students complete a senior high school entrance examination ( zhongkao ) before entering upper secondary schools. Students are assigned to different types of upper secondary schools based upon entrance examination results. In China, upper secondary education is mostly publicly funded. In 2021, 17.29% of regular senior high school students and 20.40% of secondary vocational school students were in private schools (MOE, 2022 ).

1.2.4 Higher Education

According to Article Two of Higher Education Law of the People’s Republic of China , higher education in China is defined as “education that is carried out after the completion of upper secondary education” (National People’s Congress, 2018b ). It is a general term inclusive of postsecondary education provided by academies, universities, colleges, vocational institutions, institutes of technology and certain other collegiate-level institutions, including vocational schools, trade schools, and career colleges that award academic degrees or professional certifications (Yu et al., 2012 ). In China, the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees are the three officially sanctioned higher education degrees. China’s higher education includes undergraduate education and graduate education. Within the undergraduate education system, regular higher education is the more academic route and tertiary vocational education is the more vocational route; through examination, students of tertiary vocational education can transfer to regular higher education . Students of both routes have opportunities to obtain bachelor’s degree. Graduate education system includes master’s education and doctoral education. Admissions to undergraduate education are based on students’ scores of college entrance examination ( gaokao ), and admissions to graduate education are based on students’ results of entrance examinations. In China, higher education is mostly publicly funded. In 2021, 24.19% of undergraduate students were in private HEIs (MOE, 2022 ).

1.3 The Educational Development Since the Reform and Opening-Up in 1978

1.3.1 focusing on developing education.

Providing education with concentrated strength and focus has always been the most obvious feature of “holding a large scale of education in a poor country”. In order to speed up reform within the shortest period, China adopted a plan of concentrating limited educational resources on selected schools and key fields and concentrating efforts on training in-demand skills and occupations.

Key Elementary and Secondary Schools. In January 1978, MOE stipulated the objectives, tasks, plans, enrollment methods, and leadership of key elementary and secondary schools. In October 1980, MOE sought to build approximately 700 key secondary schools as first-class, high-quality and distinctive schools with good studying habits. In July 1995, National Education Commission (the predecessor of MOE) evaluated and published a list of around 1,000 model regular senior high schools.

Projects 211 and 985 to Develop Higher Education Excellence. In 1993, the State proposed that the central government and local authorities should concentrate on running about 100 key universities and a number of core disciplines. In November 1995, Project 211 officially launched. In 1998, President Jiang Zemin put forward to establish a number of world-class universities in China. In 1999, Project 985 officially launched. These projects aimed to develop a number of excellent universities and enhance the strength of higher education.

Key Vocational Schools. In order to improve the quality of vocational education, in January 1995, the State Council proposed to carry out the evaluation and accreditation of national key secondary vocational schools, and 296 key vocational schools were selected nationwide. (Zhang, 2018 ).

1.3.2 Governing Education Development Through Laws and Regulations

Governing education development through legislation reflects the advancement of modernization in the field of education.

Within the compulsory education sector, Chinese government proposed the implementation of nine-year compulsory education in 1985, and then enacted Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1986. It took 25 years for China to develop compulsory education from the all-round “universal” stage to the quality improvement stage. As a developing country with a large population, China has realized the target of requiring nine-year compulsory education for all.

China established its higher education academic degree system in 1980. Higher Education Law of the People’s Republic of China promulgated in 1998 formulated a degree system including bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and doctoral degree, and it has become one of the most important laws to promote the development of higher education.

In the areas of preschool education, special education, and vocational education, the State Council approved the first administrative regulation of preschool education in 1989. China promulgated the first special regulation on education for the disabled in 1994 and implemented Vocational Education Law of the People’s Republic of China in 1996. ( ibid ).

1.3.3 Taking Efficiency and Equity into Consideration

With the development of education in China and the basic realization of equitable education as a starting point, the focus of education reform and development has been gradually converted from the equity of entry to the equity of educational process. Additional efforts have been made to improve the insufficient and imbalanced development of education.

Resuming College Entrance Examinations and Relaxing Restrictions on the Identity of Candidates. In 1977, the college entrance examinations were resumed. Groups including workers, peasants, and fresh high school graduates could sit for the exam as long as they match the requirements, and this change helped improve the equity of talent selection.

Eliminating the Drop-Out of Girls and Promoting Equal Education Opportunities for Men and Women. The Chinese government has actively taken actions to eliminate the dropping-out of girls and worked to effectively guarantee school-age girls’ rights to receive education.

Ensuring School-Age Children’s Right to Receive Compulsory Education . Chinese government has been working to provide more policy support and taking measures to protect school-age children’s right to receive nine-year compulsory education.

Effectively Narrowing the Gap between Regions, Urban and Rural Areas, Schools, and Groups. To narrow the educational gap between the eastern, central, and western regions, additional financial investment has been dedicated to the central and western regions, and the revitalization plans for education in the central and western regions have been implemented. To narrow the educational gap between urban and rural areas, reforms have been implemented targeting low performing rural schools and providing additional support to rural teachers. To narrow the gap between schools, low-performance schools have been given advantages in educational funding, capital construction, the acquisition of teaching equipment, and the adjustment in teaching personnel. To narrow the gap between groups, the government has vigorously encouraged and supported disadvantaged groups to receive education. ( ibid ).

1.3.4 Encouraging and Supporting Education Diversification

Education is a common cause that unites the whole of society. It is important to encouraging non-state actors to participate in and support the development of education. Running schools by non-state actors can not only ease the shortage of educational funding, but also improve the vitality of education, meet diversified educational demands, and promote the health and scientific development of education.

A series of policies provides support and encouragement to non-state actors to run schools. Article 19 of Constitution of the People’s Republic of China promulgated in 1982 stipulated, “the State encourages collective economic organizations, state enterprises and institutions, and other non-state actors to organize education in accordance with the law” (National People’s Congress, 1982 ). In 1985, Chinese central government put forward to arouse the enthusiasm of governments at all levels, teachers, students, employees, and social actors through reform. In July 1997, the State Council endorsed regulations to support and regulate non-state actors to run schools. In September 2003, Private Education Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China was promulgated and implemented, marking a new stage of legalization for China’s non-public educational sector. In 2016, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and the State Council issued regulations to actively guide non-state actors to run non-profit private schools.

In addition, non-state actors have been invited to engage in developing education at all levels. Along with making nine-year compulsory education for all, Project Hope ( Xiwang Gongcheng ) and Spring Bud Project ( Chunlei Jihua ) sprung up. Project Hope, launched by China Youth Development Foundation in 1989, sought to build Hope Elementary School ( Xiwang Xiaoxue ) and subsidize students in poverty. The Spring Bud Project was initiated by China Children and Teenagers’ Foundation in 1989 to improve education for girls from impoverished families. Currently in upper secondary education sector, the proportion between public and private education is around 8:2. ( ibid ).

2 Educational Scale in China

Based on The 2020 Overview of Educational Achievements in China and The 2021 Statistical Bulletin on National Education Development published by MOE, this section depicts the scale of China’s education from the following four aspects: literacy level, number of schools, number of students, and number of full-time teachers. Footnote 3

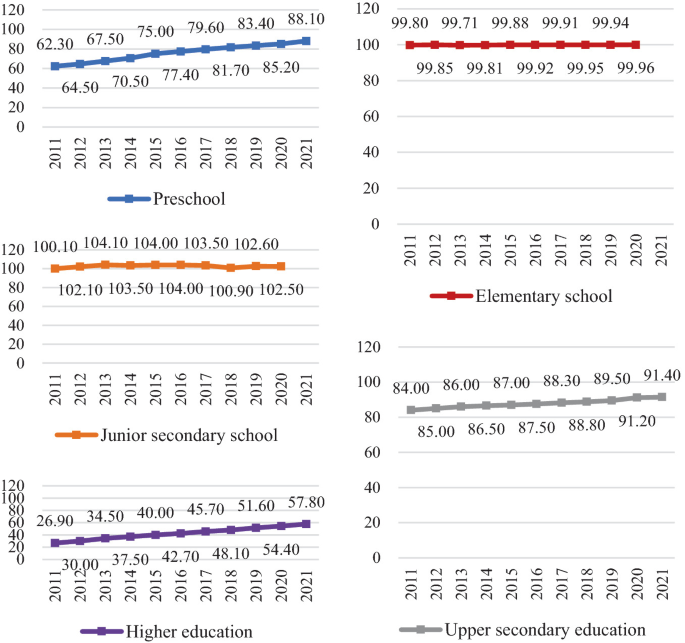

2.1 Literacy Level

Literacy level is analyzed from the following four aspects: the number of students in elementary, junior secondary schools, and upper secondary education for every 100,000 people; the enrollment ratio in elementary, junior secondary schools, upper secondary education, and higher education; the proportion of elementary and junior secondary school graduates continuing on to the next education level; the ratio of enrollment to graduation at compulsory education level. The net enrollment ratio in elementary school and the gross enrollment ratio in junior secondary school in 2020 consistently maintained at a high level, and the gross enrollment ratio in higher education reached 57.80% in 2021, which was the highest ever (Table 2 ).

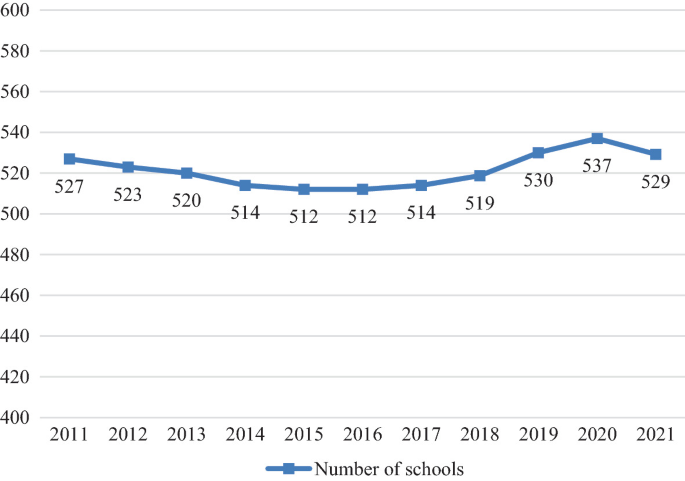

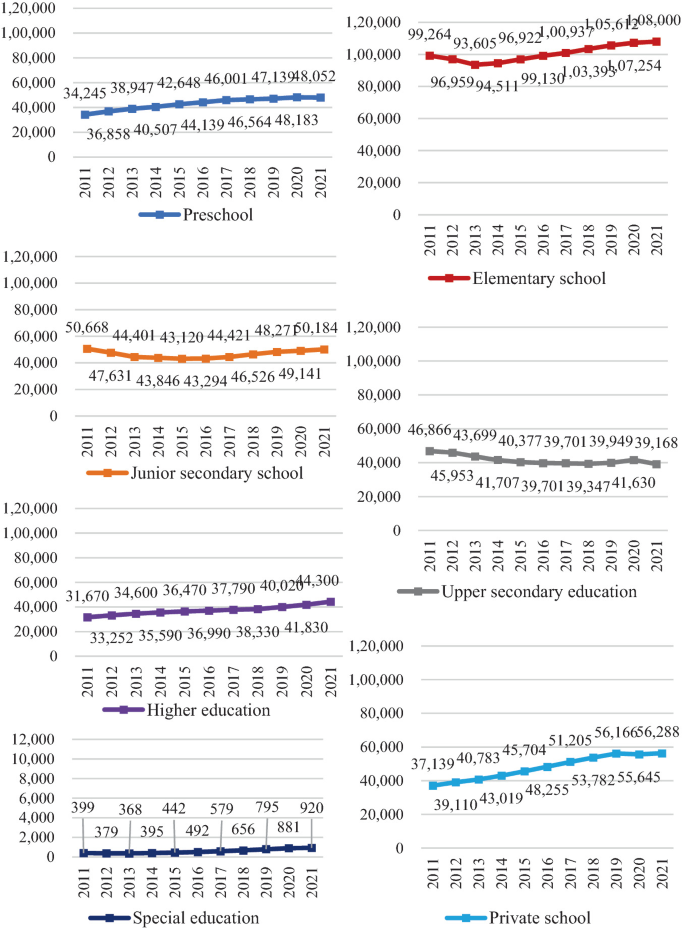

2.2 Number of Schools by Educational Sector and Level

Table 3 shows the number of schools by educational sector and level in 2021. The number of preschools reached 294,800, which was the largest ever. The number of schools of compulsory education was the second largest, with elementary schools representing three fourths and junior secondary schools representing one fourth. In upper secondary education, the number of regular senior high schools was larger than that of secondary vocational schools. In higher education, the number of HEIs reached 3,012 and seven of them are world-class universities.

2.3 Number of Students by Educational Sector and Level

Table 4 shows the number of students by educational sector and level in 2021. The number of compulsory education students reached over 158 million and the number of higher education students reached 44.3 million, which were the largest ever. In upper secondary education, the number of regular senior high school students was larger than that of secondary vocational school students.

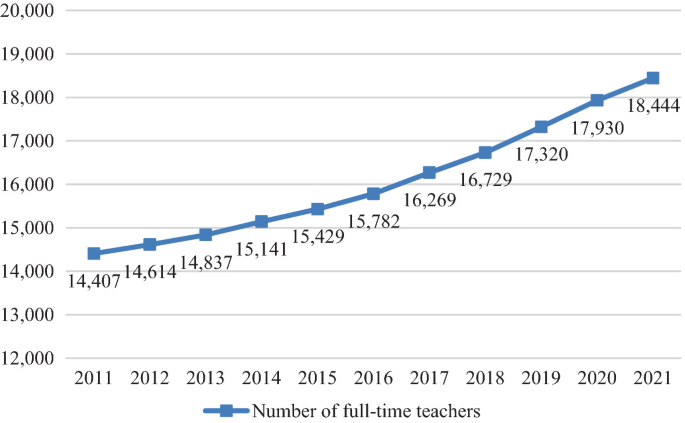

2.4 Number of Full-Time Teachers by Educational Sector and Level

Table 5 shows the number of full-time teachers by educational sector and level in 2021. The number of full-time teachers in compulsory education was the largest among all categories. In 2021, excluding upper secondary education, the number of every category was the largest ever.

3 Educational Resources in China

Based on The 2020 Statistical Bulletin on Education Spending co-released by MOE, National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), and Ministry of Finance (MOF) in 2021, and The 2020 Overview of Educational Achievements in China published by MOE in 2021, this section depicts educational resources in China from the following four aspects: the overall spending on education, the general public expenditure on education, the general public operating expenditure on education per student, and school infrastructure. Footnote 4

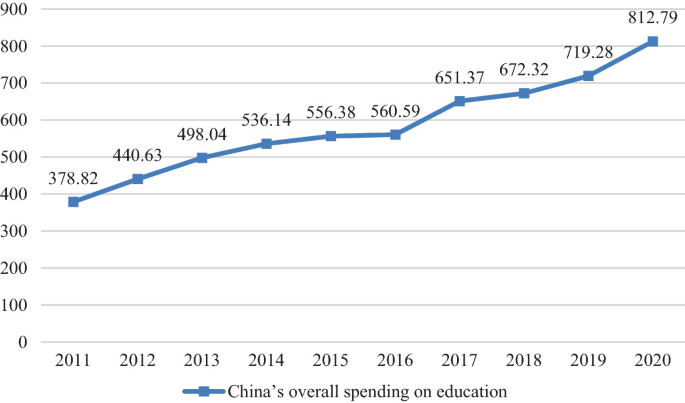

3.1 Overall Spending on Education

Table 6 shows China’s overall spending on education in 2020. The overall spending on education nationwide reached US$812.79 billion, the spending on education from national budget reached US$657.61 billion, and the spending on education from national budget represented 4.22% in China’s GDP in 2020.

3.2 General Public Expenditure on Education

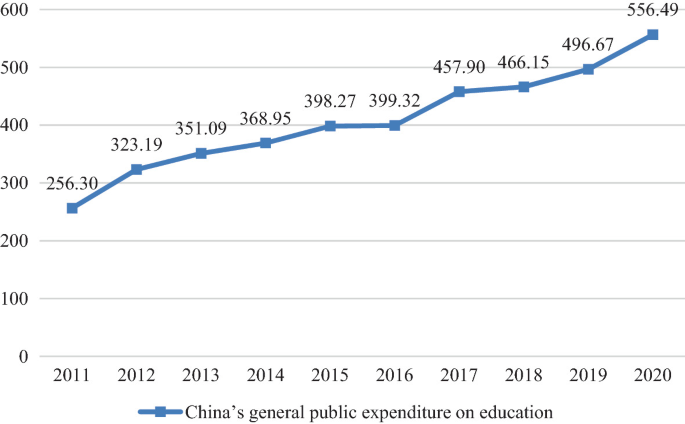

Table 7 shows China’s general public expenditure on education in 2020. The general public expenditure on education reached US$556.49 billion and it represented 14.78% in national public budget in 2020.

Table 8 shows the general public expenditure on education per student in schools by educational sector and level in 2020.The figure for higher education was the highest, while preschool was the lowest. The expenditures on elementary and junior secondary school in rural area were lower than the average number of that education level.

3.3 General Public Operating Expenditure on Education Per Student

Table 9 shows the general public operating expenditure on education per student in schools by educational sector and level in 2020. The expenditure on higher education was the highest, while preschool was the lowest. The figures for elementary and junior secondary school in rural area were slightly lower than the average number of that education level.

3.4 School Infrastructure

Table 10 illustrates the space utilization and equipment in schools by educational sector and level in 2020. The average value and average number of instructional equipment per student increased with the level of education. It is worth noting that the average value of teaching and scientific research equipment per student at secondary vocational schools was higher than that of regular senior high school.

4 Scientific Research in China

4.1 scientific research development at china’s heis.

Over the past four decades since reform and opening-up, China has gradually established a national innovation system. During this time, HEIs have become more and more important in scientific and technological innovation. This section reviews the technological policies in five important stages since 1978.

4.1.1 Stage One: Restoring the Scientific Research Function of HEIs (1978–1984)

In 1978, Chinese central government formulated the outline of national plan for science and technology development during the period from 1978 to 1985. Deng Xiaoping, the leader of China at the time, put forward strategies including “science and technology are elementary productive force” and “the key of the four modernizations is the modernization of science and technology”, which promote the restoration and development of science and technology system. During this period, the function of scientific research of HEIs has gradually been restored. In 1977, Deng Xiaoping expressed support for increased research activity by stating, “key higher education institutions are significant in scientific research and should undertake more scientific research tasks.” Since then, HEIs have been allocated with budget appropriation for scientific research from national funds, marking an official change and the restoration of HEI’s role in scientific research. In 1978, National Education Commission, National Science Commission (the predecessor of Ministry of Science and Technology [MOST]), and MOF decided to allocate RMB30 million from “the three types of expenses of science and technology” (which include the expense of new product experiment, the expense of semi-plant test, and key scientific research subsidies) to HEIs, in order to promote important scientific research and experiment. Scientific research has been included in the operating expenditure on higher education since 1979, and the appropriation for scientific research was RMB14.15 million that year. In 1985, the scientific research fund for HEIs was nearly RMB600 million (Yin & Shen, 2005 ).

4.1.2 Stage Two: Establishing Research Universities (1985–1994)

In 1985, Chinese government advocated, “higher education institutions and Chinese Academy of Sciences take important responsibilities for basic research and applied research. Basic research and applied research should be tightly combined with workforce needs. Higher education institutions that meet certain conditions are encouraged to construct distinctive and effective research institutes”. In September 1991, the State Council pointed out that, “higher education institutions should pay great attention to scientific research work and regard it as basic tasks”, “higher education institutions with a large number of key disciplines, important assignments of training graduate students, and good foundations for teaching and scientific research, should be developed into the center of education and the center of scientific research. They should take major responsibilities for scientific and technological tasks and train high-level talents for the country. They should also take the lead in improving China’s strength of science and technology and the quality of higher education” (Yin, 2005 ). In order to promote the development of scientific research in HEIs in the early 1990s, the Chinese government developed policy-level plans to invest special funds to construct research universities. In December 1991, National Planning Commission (the predecessor of National Development and Reform Commission [NDRC]), National Education Commission, and MOF proposed to the State Council that they all “agree to the country’s decision of establishing key universities and key disciplines that are required for national economic and social development”. In 1993, The Outline of China’s Education Reform and Development suggested the central government and local governments should jointly establish 100 strategic universities. All of these policies made a foundation for the formulation of the ensuring Project 211 of higher education (MOE, 2008 ).

4.1.3 Stage Three: Implementing National Initiatives to Further Develop Research Universities (1995–2004)

To reinforce Chinese higher education’s competitiveness in the global stage, Chinese government implemented a series of special plans to support the establishment of research universities. In November 1995, the overall plan for Project 211 was published, which suggested the central government and local governments should jointly establish around 100 key universities and a number of key disciplines that reach world-class level (MOE, 2008 ).

In December 1998, MOE put forward a goal of developing a number of key universities and key disciplines into world-class level in the following 10–20 years. In January 1999, the State Council ratified Project 985 of higher education.

During the period of the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005) , China allocated considerable funding for the construction of Project 211 and Project 985. In 2001, the Education Work Conference proposed to strengthen the development of leading universities and key disciplines, make key discipline as the core and speed up the development (MOE, 2008 ). In 2004, the second phase of Project 985 was launched, which expanded the university list and a total of 39 universities were included and put forward five aspects of goals in developing world-class universities: mechanism innovation, talent training, platform establishment, supportive conditions, and international communication and cooperation (Yuan & Guo, 2012 ).

After nearly a decade of development, a number of Chinese HEIs had followed the direction of developing world-class universities and markedly improved their level of scientific research. By investigating the scale and influence of scientific research of China’s research universities from 1997 to 2006, it can be seen that the amount of scientific research achievements of China’s research universities had increased by nearly five times during decade, and the influence of scientific research achievements had continued to be enhanced during the period, while the turning point of scientific research output is basically the same as the time point of constructing Project 985 (Zhu & Liu, 2009 ).

4.1.4 Stage Four: Serving National Innovation System (2005–2014)

In 2005, the State Council published an outline of national plan for science and technology development in the period of 2006–2020 and proposed the general goal of “establishing national innovation system” (MOST, 2006 ).

While establishing a national innovation system, universities, especially research universities, were required to realize new targets. The State Council pointed out, “universities are important base of training high-level innovative talents, and they are one of the main forces of basic research and high-tech innovation.” Based on the demand of establishing national innovation system, Chinese universities were not only required to improve the strength of scientific research, but also required to form an innovation system collaboratively with enterprises and government (MOST, 2006 ). In 2008, NDRC, MOE, and MOF launched the third phase of Project 211, and it aimed at building China into an innovative country, as it strengthened the construction of key disciplines, innovative talents and personnel, and the public service system of higher education (MOST, 2006 ). MOE and other related ministries proposed the 2011 Plan in 2012. The 2011 Plan originated from “the urgent demand of the country and the requirement of reaching world-class level”, it was based on the trinity of improving the innovative capacity of talents, disciplines, and scientific research, and it aims at improving the quality of higher education and serving the development of economy and society (MOE, 2014 ).

4.1.5 Stage Five: Further Developing World-Class Universities and Disciplines (2015-Present)

In October 2015, the State Council issued The Overall Plan for Promoting the Construction of World-Class Universities and World-Class Disciplines and proposed to “promote a number of leading universities and disciplines to get into the first class or the front class in the world” (the State Council, 2015 ). It put forward the following goals: to develop a number of world-class universities and first-class academic disciplines by 2020; to have more universities and disciplines among the world’s best and to enhance the country’s overall higher education capacity by 2030; and to lead the number, quality and capacity of world-class universities and disciplines among the world’s best, becoming a higher education powerhouse by 2050 (the State Council, 2015 ).

In September 2017, MOE, MOF, and NDRC published the list of the Double World-Class Project, which selected 42 universities aiming for world-class status and 140 universities that were designated to develop world-class disciplines (MOE et al., 2017 ). In February 2022, the list of the second round of the Double World-Class Project was published, which selected more than 400 disciplines from 147 universities (MOE et al., 2022 ). The purpose of the Double World-Class Project is to support the national strategy of innovation-driven development, improve the level of educational development, strengthen the core competitiveness of the country, and realize the great development of China from a large country in higher education to a powerful country in higher education.

4.2 Research Performance of China’s HEIs

4.2.1 science and technology (s&t) research output.

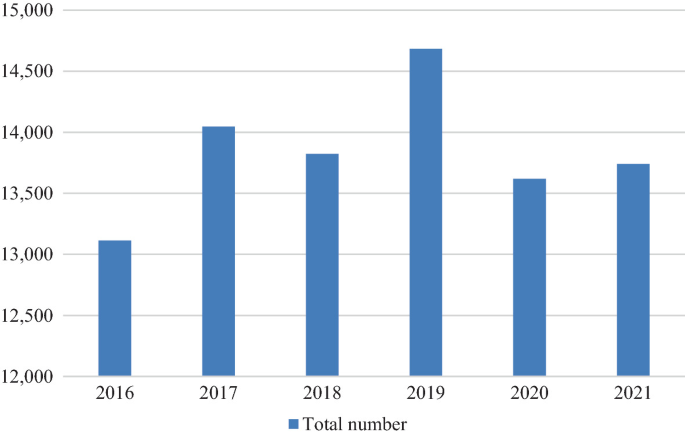

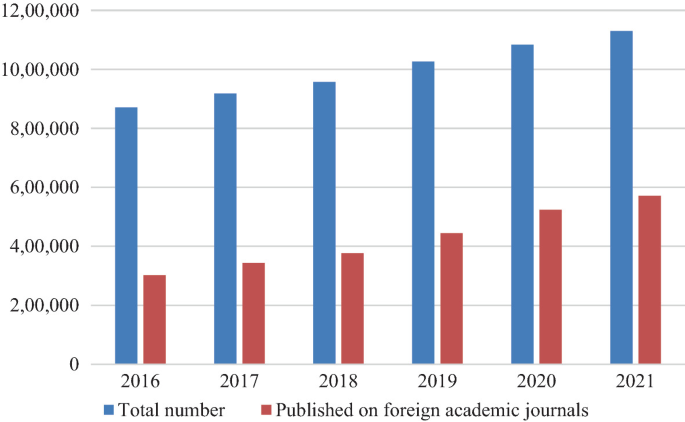

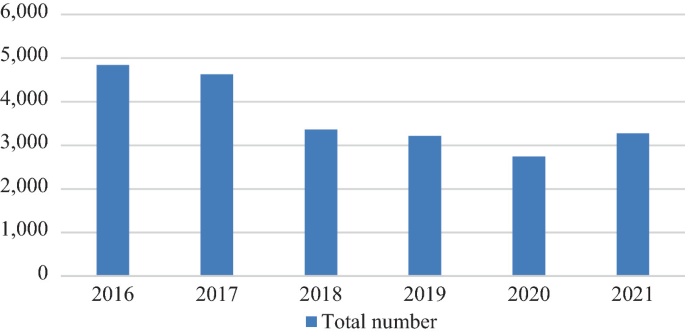

Scientific and technological achievements refer to the output of scientific and technological research created by scientific and technological personnel. The scientific and technological achievements at China’s HEIs mainly include four categories: scientific and technological books, academic papers, international projects completed and approved, and intellectual property rights and patents.

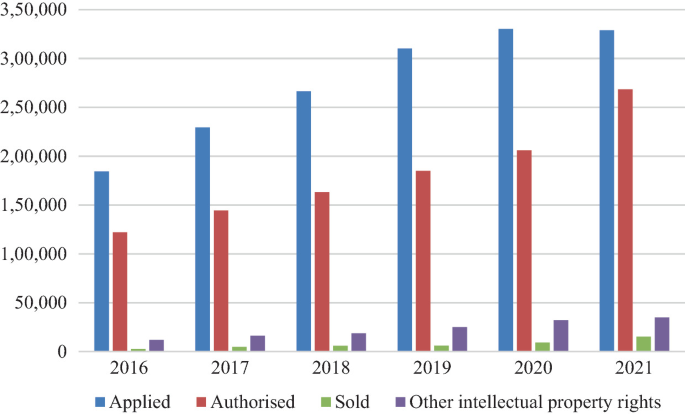

In 2021, China’s HEIs published 13,740 scientific and technological books; published 1,129,917 academic papers, of which 571,696 were published on foreign academic journals. A total of 3,271 international projects were completed and approved. In 2021, China’s HEIs applied 328,896 patents, of which 268,450 were authorized and 15,169 were sold. The number of other intellectual property rights (include software registration, integrated circuit design registration, new animal and plant varieties registration, and national new drug registration, etc.) that China’s HEIs acquired in 2021 was 34,915. (Department of Science, Technology and Informatization [DSTI], 2022 ).

4.2.2 Innovative Talent Development in S&T

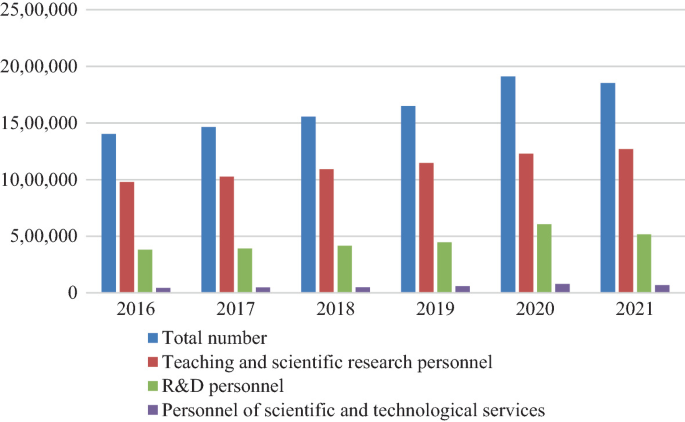

Scientific and technological talents refer to the personnel who directly participate in scientific and technological activities in related institutions or departments and are paid, including scientists, engineers, technicians, and auxiliary personnel (UNESCO, 2014 ). In statistics, the scientific and technological workforce at China’s HEIs can be divided into three categories: teaching and scientific research personnel, R&D personnel, and personnel of scientific and technological services.

In 2021, the total number of scientific and technological workforce of China’s HEIs was approximately 1.85 million. The number of teaching and scientific research personnel was 1,268,970, accounting for around 69%; the number of R&D personnel was 516,101, accounting for around 28%; and around 3% of the total workforce was personnel of scientific and technological services, with the number of 67,038. (DSTI, 2022 ).

4.2.3 S&T Innovation Platforms

The scientific and technological innovation platforms at China’s HEIs mainly include national key laboratories, national engineering technology research centers, key laboratories of MOE, key laboratories on provincial and ministerial levels, engineering technology research centers on provincial and ministerial levels, and research institutes built by schools. (Wu & Tang, 2006 ).

4.2.4 S&T Projects at China’s HEIs

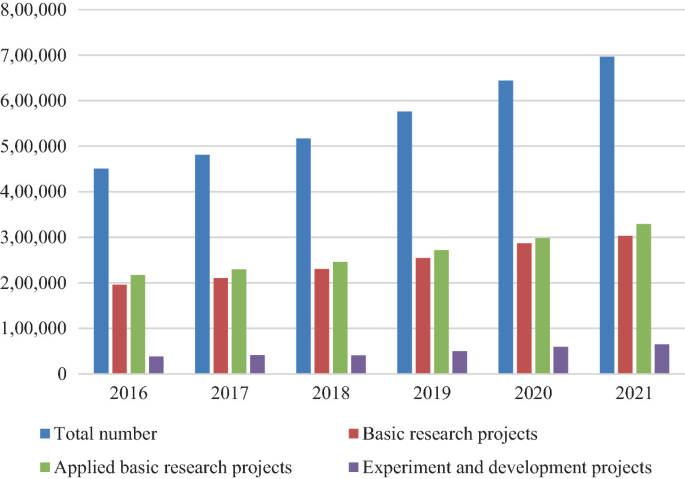

Scientific and technological projects refer to the research and experiment and development works that aim at solving complex and comprehensive scientific and technological problems. Scientific and technological projects at China’s HEIs mainly include three categories: basic research project, applied basic research project, and experiment and development project.

In 2021, the total number of scientific and technological projects of China’s HEIs was 696,714. The number of basic research projects was 303,197, accounting for around 44% of the total; the number of applied basic research projects was 328,869, accounting for around 47%; the number of experiment and development projects was 64,648, accounting for around 9%. (DSTI, 2022 ).

5 Trends of Chinese Education

5.1 trends in educational scale.

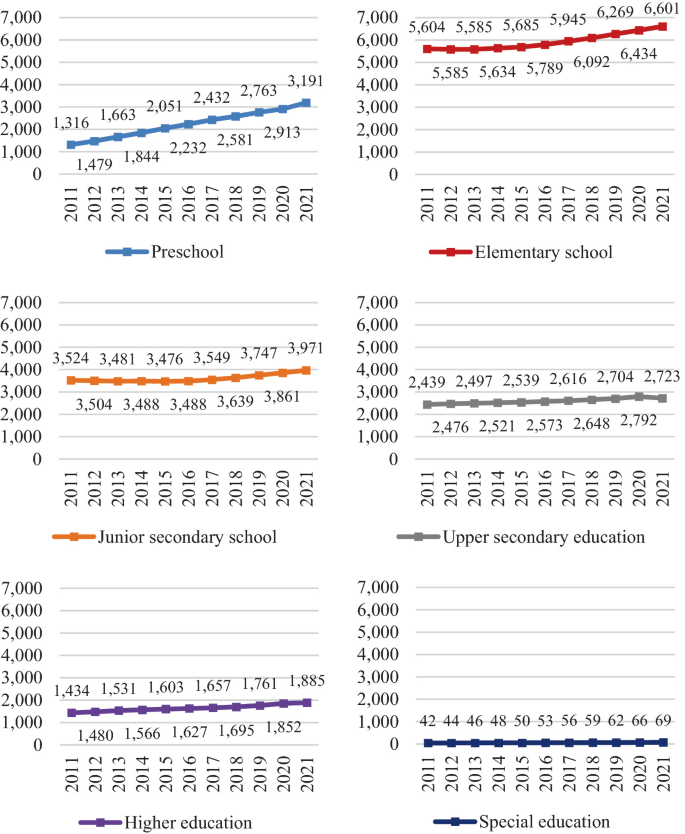

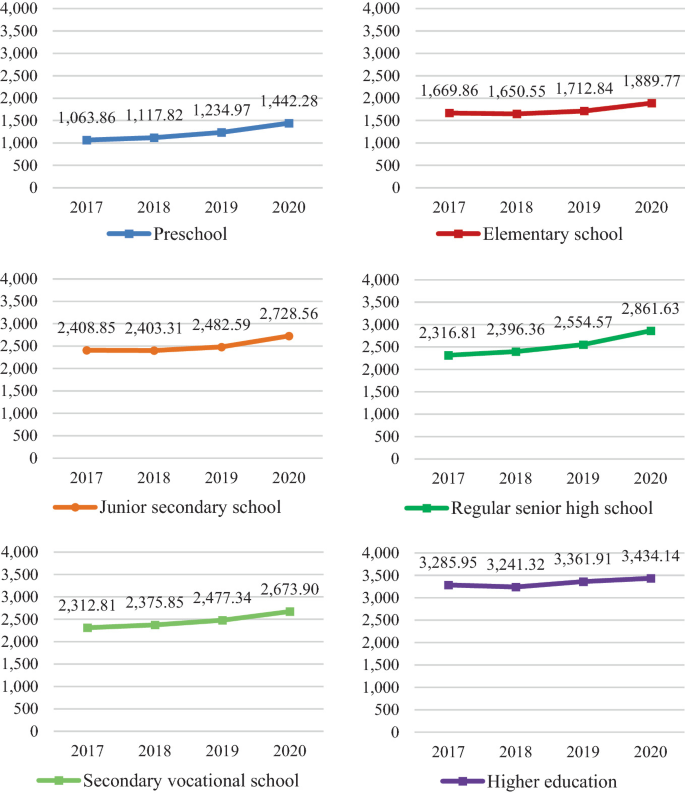

Based on The Overview of Educational Achievements in China and The Statistical Bulletin on National Education Development published by MOE from 2012 to 2022, this section analyses changes in education scale in the Chinese mainland from the following four aspects: gross enrollment ratios in schools by educational sector and level, number of schools, number of students, and number of full-time teachers.

5.1.1 Gross Enrollment Ratio

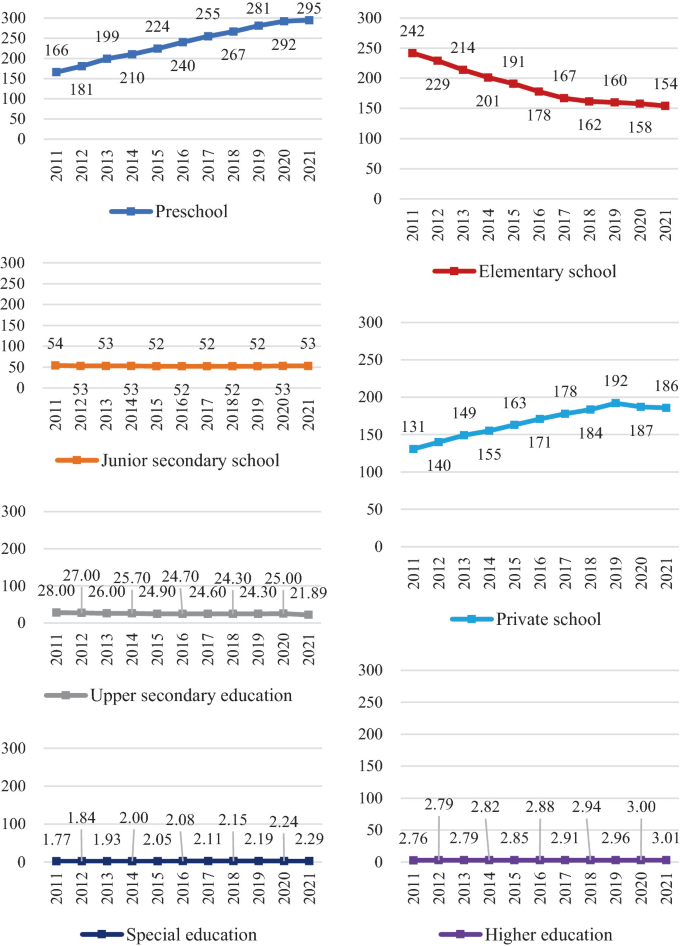

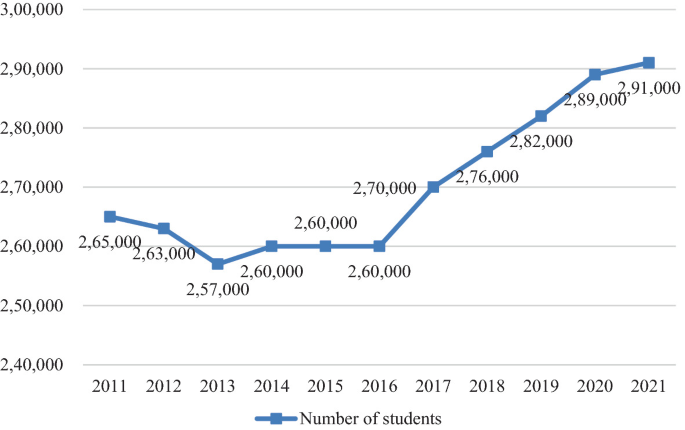

Figure 2 shows the enrollment ratios of schools by educational sector and level during the period from 2011 to 2021. The figures for elementary school and junior secondary school remained stable on a high level. The figures for preschool and upper secondary education consistently increased during the period. It is noticeable that the gross enrollment ratio of higher education rose rapidly and the figure for 2021 doubled that for 2011.