Advertisement

The effects of online education on academic success: A meta-analysis study

- Published: 06 September 2021

- Volume 27 , pages 429–450, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Hakan Ulum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1398-6935 1

82k Accesses

30 Citations

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The purpose of this study is to analyze the effect of online education, which has been extensively used on student achievement since the beginning of the pandemic. In line with this purpose, a meta-analysis of the related studies focusing on the effect of online education on students’ academic achievement in several countries between the years 2010 and 2021 was carried out. Furthermore, this study will provide a source to assist future studies with comparing the effect of online education on academic achievement before and after the pandemic. This meta-analysis study consists of 27 studies in total. The meta-analysis involves the studies conducted in the USA, Taiwan, Turkey, China, Philippines, Ireland, and Georgia. The studies included in the meta-analysis are experimental studies, and the total sample size is 1772. In the study, the funnel plot, Duval and Tweedie’s Trip and Fill Analysis, Orwin’s Safe N Analysis, and Egger’s Regression Test were utilized to determine the publication bias, which has been found to be quite low. Besides, Hedge’s g statistic was employed to measure the effect size for the difference between the means performed in accordance with the random effects model. The results of the study show that the effect size of online education on academic achievement is on a medium level. The heterogeneity test results of the meta-analysis study display that the effect size does not differ in terms of class level, country, online education approaches, and lecture moderators.

Explore related subjects

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Information and communication technologies have become a powerful force in transforming the educational settings around the world. The pandemic has been an important factor in transferring traditional physical classrooms settings through adopting information and communication technologies and has also accelerated the transformation. The literature supports that learning environments connected to information and communication technologies highly satisfy students. Therefore, we need to keep interest in technology-based learning environments. Clearly, technology has had a huge impact on young people's online lives. This digital revolution can synergize the educational ambitions and interests of digitally addicted students. In essence, COVID-19 has provided us with an opportunity to embrace online learning as education systems have to keep up with the rapid emergence of new technologies.

Information and communication technologies that have an effect on all spheres of life are also actively included in the education field. With the recent developments, using technology in education has become inevitable due to personal and social reasons (Usta, 2011a ). Online education may be given as an example of using information and communication technologies as a consequence of the technological developments. Also, it is crystal clear that online learning is a popular way of obtaining instruction (Demiralay et al., 2016 ; Pillay et al., 2007 ), which is defined by Horton ( 2000 ) as a way of education that is performed through a web browser or an online application without requiring an extra software or a learning source. Furthermore, online learning is described as a way of utilizing the internet to obtain the related learning sources during the learning process, to interact with the content, the teacher, and other learners, as well as to get support throughout the learning process (Ally, 2004 ). Online learning has such benefits as learning independently at any time and place (Vrasidas & MsIsaac, 2000 ), granting facility (Poole, 2000 ), flexibility (Chizmar & Walbert, 1999 ), self-regulation skills (Usta, 2011b ), learning with collaboration, and opportunity to plan self-learning process.

Even though online education practices have not been comprehensive as it is now, internet and computers have been used in education as alternative learning tools in correlation with the advances in technology. The first distance education attempt in the world was initiated by the ‘Steno Courses’ announcement published in Boston newspaper in 1728. Furthermore, in the nineteenth century, Sweden University started the “Correspondence Composition Courses” for women, and University Correspondence College was afterwards founded for the correspondence courses in 1843 (Arat & Bakan, 2011 ). Recently, distance education has been performed through computers, assisted by the facilities of the internet technologies, and soon, it has evolved into a mobile education practice that is emanating from progress in the speed of internet connection, and the development of mobile devices.

With the emergence of pandemic (Covid-19), face to face education has almost been put to a halt, and online education has gained significant importance. The Microsoft management team declared to have 750 users involved in the online education activities on the 10 th March, just before the pandemic; however, on March 24, they informed that the number of users increased significantly, reaching the number of 138,698 users (OECD, 2020 ). This event supports the view that it is better to commonly use online education rather than using it as a traditional alternative educational tool when students do not have the opportunity to have a face to face education (Geostat, 2019 ). The period of Covid-19 pandemic has emerged as a sudden state of having limited opportunities. Face to face education has stopped in this period for a long time. The global spread of Covid-19 affected more than 850 million students all around the world, and it caused the suspension of face to face education. Different countries have proposed several solutions in order to maintain the education process during the pandemic. Schools have had to change their curriculum, and many countries supported the online education practices soon after the pandemic. In other words, traditional education gave its way to online education practices. At least 96 countries have been motivated to access online libraries, TV broadcasts, instructions, sources, video lectures, and online channels (UNESCO, 2020 ). In such a painful period, educational institutions went through online education practices by the help of huge companies such as Microsoft, Google, Zoom, Skype, FaceTime, and Slack. Thus, online education has been discussed in the education agenda more intensively than ever before.

Although online education approaches were not used as comprehensively as it has been used recently, it was utilized as an alternative learning approach in education for a long time in parallel with the development of technology, internet and computers. The academic achievement of the students is often aimed to be promoted by employing online education approaches. In this regard, academicians in various countries have conducted many studies on the evaluation of online education approaches and published the related results. However, the accumulation of scientific data on online education approaches creates difficulties in keeping, organizing and synthesizing the findings. In this research area, studies are being conducted at an increasing rate making it difficult for scientists to be aware of all the research outside of their expertise. Another problem encountered in the related study area is that online education studies are repetitive. Studies often utilize slightly different methods, measures, and/or examples to avoid duplication. This erroneous approach makes it difficult to distinguish between significant differences in the related results. In other words, if there are significant differences in the results of the studies, it may be difficult to express what variety explains the differences in these results. One obvious solution to these problems is to systematically review the results of various studies and uncover the sources. One method of performing such systematic syntheses is the application of meta-analysis which is a methodological and statistical approach to draw conclusions from the literature. At this point, how effective online education applications are in increasing the academic success is an important detail. Has online education, which is likely to be encountered frequently in the continuing pandemic period, been successful in the last ten years? If successful, how much was the impact? Did different variables have an impact on this effect? Academics across the globe have carried out studies on the evaluation of online education platforms and publishing the related results (Chiao et al., 2018 ). It is quite important to evaluate the results of the studies that have been published up until now, and that will be published in the future. Has the online education been successful? If it has been, how big is the impact? Do the different variables affect this impact? What should we consider in the next coming online education practices? These questions have all motivated us to carry out this study. We have conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis study that tries to provide a discussion platform on how to develop efficient online programs for educators and policy makers by reviewing the related studies on online education, presenting the effect size, and revealing the effect of diverse variables on the general impact.

There have been many critical discussions and comprehensive studies on the differences between online and face to face learning; however, the focus of this paper is different in the sense that it clarifies the magnitude of the effect of online education and teaching process, and it represents what factors should be controlled to help increase the effect size. Indeed, the purpose here is to provide conscious decisions in the implementation of the online education process.

The general impact of online education on the academic achievement will be discovered in the study. Therefore, this will provide an opportunity to get a general overview of the online education which has been practiced and discussed intensively in the pandemic period. Moreover, the general impact of online education on academic achievement will be analyzed, considering different variables. In other words, the current study will allow to totally evaluate the study results from the related literature, and to analyze the results considering several cultures, lectures, and class levels. Considering all the related points, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

What is the effect size of online education on academic achievement?

How do the effect sizes of online education on academic achievement change according to the moderator variable of the country?

How do the effect sizes of online education on academic achievement change according to the moderator variable of the class level?

How do the effect sizes of online education on academic achievement change according to the moderator variable of the lecture?

How do the effect sizes of online education on academic achievement change according to the moderator variable of the online education approaches?

This study aims at determining the effect size of online education, which has been highly used since the beginning of the pandemic, on students’ academic achievement in different courses by using a meta-analysis method. Meta-analysis is a synthesis method that enables gathering of several study results accurately and efficiently, and getting the total results in the end (Tsagris & Fragkos, 2018 ).

2.1 Selecting and coding the data (studies)

The required literature for the meta-analysis study was reviewed in July, 2020, and the follow-up review was conducted in September, 2020. The purpose of the follow-up review was to include the studies which were published in the conduction period of this study, and which met the related inclusion criteria. However, no study was encountered to be included in the follow-up review.

In order to access the studies in the meta-analysis, the databases of Web of Science, ERIC, and SCOPUS were reviewed by utilizing the keywords ‘online learning and online education’. Not every database has a search engine that grants access to the studies by writing the keywords, and this obstacle was considered to be an important problem to be overcome. Therefore, a platform that has a special design was utilized by the researcher. With this purpose, through the open access system of Cukurova University Library, detailed reviews were practiced using EBSCO Information Services (EBSCO) that allow reviewing the whole collection of research through a sole searching box. Since the fundamental variables of this study are online education and online learning, the literature was systematically reviewed in the related databases (Web of Science, ERIC, and SCOPUS) by referring to the keywords. Within this scope, 225 articles were accessed, and the studies were included in the coding key list formed by the researcher. The name of the researchers, the year, the database (Web of Science, ERIC, and SCOPUS), the sample group and size, the lectures that the academic achievement was tested in, the country that the study was conducted in, and the class levels were all included in this coding key.

The following criteria were identified to include 225 research studies which were coded based on the theoretical basis of the meta-analysis study: (1) The studies should be published in the refereed journals between the years 2020 and 2021, (2) The studies should be experimental studies that try to determine the effect of online education and online learning on academic achievement, (3) The values of the stated variables or the required statistics to calculate these values should be stated in the results of the studies, and (4) The sample group of the study should be at a primary education level. These criteria were also used as the exclusion criteria in the sense that the studies that do not meet the required criteria were not included in the present study.

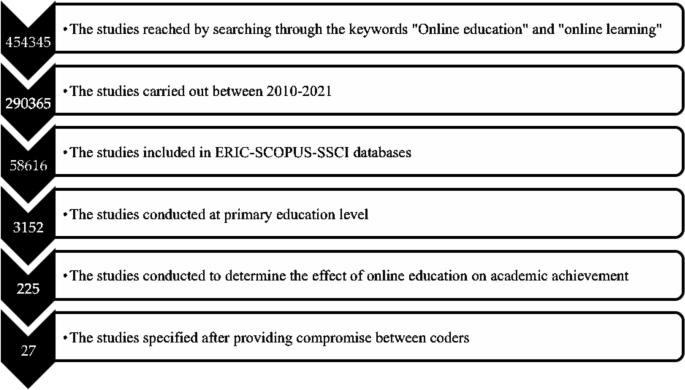

After the inclusion criteria were determined, a systematic review process was conducted, following the year criterion of the study by means of EBSCO. Within this scope, 290,365 studies that analyze the effect of online education and online learning on academic achievement were accordingly accessed. The database (Web of Science, ERIC, and SCOPUS) was also used as a filter by analyzing the inclusion criteria. Hence, the number of the studies that were analyzed was 58,616. Afterwards, the keyword ‘primary education’ was used as the filter and the number of studies included in the study decreased to 3152. Lastly, the literature was reviewed by using the keyword ‘academic achievement’ and 225 studies were accessed. All the information of 225 articles was included in the coding key.

It is necessary for the coders to review the related studies accurately and control the validity, safety, and accuracy of the studies (Stewart & Kamins, 2001 ). Within this scope, the studies that were determined based on the variables used in this study were first reviewed by three researchers from primary education field, then the accessed studies were combined and processed in the coding key by the researcher. All these studies that were processed in the coding key were analyzed in accordance with the inclusion criteria by all the researchers in the meetings, and it was decided that 27 studies met the inclusion criteria (Atici & Polat, 2010 ; Carreon, 2018 ; Ceylan & Elitok Kesici, 2017 ; Chae & Shin, 2016 ; Chiang et al. 2014 ; Ercan, 2014 ; Ercan et al., 2016 ; Gwo-Jen et al., 2018 ; Hayes & Stewart, 2016 ; Hwang et al., 2012 ; Kert et al., 2017 ; Lai & Chen, 2010 ; Lai et al., 2015 ; Meyers et al., 2015 ; Ravenel et al., 2014 ; Sung et al., 2016 ; Wang & Chen, 2013 ; Yu, 2019 ; Yu & Chen, 2014 ; Yu & Pan, 2014 ; Yu et al., 2010 ; Zhong et al., 2017 ). The data from the studies meeting the inclusion criteria were independently processed in the second coding key by three researchers, and consensus meetings were arranged for further discussion. After the meetings, researchers came to an agreement that the data were coded accurately and precisely. Having identified the effect sizes and heterogeneity of the study, moderator variables that will show the differences between the effect sizes were determined. The data related to the determined moderator variables were added to the coding key by three researchers, and a new consensus meeting was arranged. After the meeting, researchers came to an agreement that moderator variables were coded accurately and precisely.

2.2 Study group

27 studies are included in the meta-analysis. The total sample size of the studies that are included in the analysis is 1772. The characteristics of the studies included are given in Table 1 .

2.3 Publication bias

Publication bias is the low capability of published studies on a research subject to represent all completed studies on the same subject (Card, 2011 ; Littell et al., 2008 ). Similarly, publication bias is the state of having a relationship between the probability of the publication of a study on a subject, and the effect size and significance that it produces. Within this scope, publication bias may occur when the researchers do not want to publish the study as a result of failing to obtain the expected results, or not being approved by the scientific journals, and consequently not being included in the study synthesis (Makowski et al., 2019 ). The high possibility of publication bias in a meta-analysis study negatively affects (Pecoraro, 2018 ) the accuracy of the combined effect size, causing the average effect size to be reported differently than it should be (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). For this reason, the possibility of publication bias in the included studies was tested before determining the effect sizes of the relationships between the stated variables. The possibility of publication bias of this meta-analysis study was analyzed by using the funnel plot, Orwin’s Safe N Analysis, Duval and Tweedie’s Trip and Fill Analysis, and Egger’s Regression Test.

2.4 Selecting the model

After determining the probability of publication bias of this meta-analysis study, the statistical model used to calculate the effect sizes was selected. The main approaches used in the effect size calculations according to the differentiation level of inter-study variance are fixed and random effects models (Pigott, 2012 ). Fixed effects model refers to the homogeneity of the characteristics of combined studies apart from the sample sizes, while random effects model refers to the parameter diversity between the studies (Cumming, 2012 ). While calculating the average effect size in the random effects model (Deeks et al., 2008 ) that is based on the assumption that effect predictions of different studies are only the result of a similar distribution, it is necessary to consider several situations such as the effect size apart from the sample error of combined studies, characteristics of the participants, duration, scope, and pattern of the study (Littell et al., 2008 ). While deciding the model in the meta-analysis study, the assumptions on the sample characteristics of the studies included in the analysis and the inferences that the researcher aims to make should be taken into consideration. The fact that the sample characteristics of the studies conducted in the field of social sciences are affected by various parameters shows that using random effects model is more appropriate in this sense. Besides, it is stated that the inferences made with the random effects model are beyond the studies included in the meta-analysis (Field, 2003 ; Field & Gillett, 2010 ). Therefore, using random effects model also contributes to the generalization of research data. The specified criteria for the statistical model selection show that according to the nature of the meta-analysis study, the model should be selected just before the analysis (Borenstein et al., 2007 ; Littell et al., 2008 ). Within this framework, it was decided to make use of the random effects model, considering that the students who are the samples of the studies included in the meta-analysis are from different countries and cultures, the sample characteristics of the studies differ, and the patterns and scopes of the studies vary as well.

2.5 Heterogeneity

Meta-analysis facilitates analyzing the research subject with different parameters by showing the level of diversity between the included studies. Within this frame, whether there is a heterogeneous distribution between the studies included in the study or not has been evaluated in the present study. The heterogeneity of the studies combined in this meta-analysis study has been determined through Q and I 2 tests. Q test evaluates the random distribution probability of the differences between the observed results (Deeks et al., 2008 ). Q value exceeding 2 value calculated according to the degree of freedom and significance, indicates the heterogeneity of the combined effect sizes (Card, 2011 ). I 2 test, which is the complementary of the Q test, shows the heterogeneity amount of the effect sizes (Cleophas & Zwinderman, 2017 ). I 2 value being higher than 75% is explained as high level of heterogeneity.

In case of encountering heterogeneity in the studies included in the meta-analysis, the reasons of heterogeneity can be analyzed by referring to the study characteristics. The study characteristics which may be related to the heterogeneity between the included studies can be interpreted through subgroup analysis or meta-regression analysis (Deeks et al., 2008 ). While determining the moderator variables, the sufficiency of the number of variables, the relationship between the moderators, and the condition to explain the differences between the results of the studies have all been considered in the present study. Within this scope, it was predicted in this meta-analysis study that the heterogeneity can be explained with the country, class level, and lecture moderator variables of the study in terms of the effect of online education, which has been highly used since the beginning of the pandemic, and it has an impact on the students’ academic achievement in different lectures. Some subgroups were evaluated and categorized together, considering that the number of effect sizes of the sub-dimensions of the specified variables is not sufficient to perform moderator analysis (e.g. the countries where the studies were conducted).

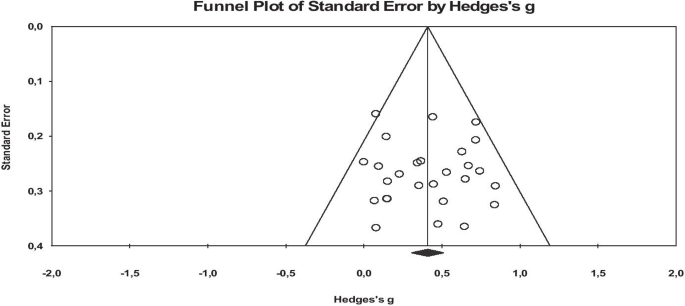

2.6 Interpreting the effect sizes

Effect size is a factor that shows how much the independent variable affects the dependent variable positively or negatively in each included study in the meta-analysis (Dinçer, 2014 ). While interpreting the effect sizes obtained from the meta-analysis, the classifications of Cohen et al. ( 2007 ) have been utilized. The case of differentiating the specified relationships of the situation of the country, class level, and school subject variables of the study has been identified through the Q test, degree of freedom, and p significance value Fig. 1 and 2 .

3 Findings and results

The purpose of this study is to determine the effect size of online education on academic achievement. Before determining the effect sizes in the study, the probability of publication bias of this meta-analysis study was analyzed by using the funnel plot, Orwin’s Safe N Analysis, Duval and Tweedie’s Trip and Fill Analysis, and Egger’s Regression Test.

When the funnel plots are examined, it is seen that the studies included in the analysis are distributed symmetrically on both sides of the combined effect size axis, and they are generally collected in the middle and lower sections. The probability of publication bias is low according to the plots. However, since the results of the funnel scatter plots may cause subjective interpretations, they have been supported by additional analyses (Littell et al., 2008 ). Therefore, in order to provide an extra proof for the probability of publication bias, it has been analyzed through Orwin’s Safe N Analysis, Duval and Tweedie’s Trip and Fill Analysis, and Egger’s Regression Test (Table 2 ).

Table 2 consists of the results of the rates of publication bias probability before counting the effect size of online education on academic achievement. According to the table, Orwin Safe N analysis results show that it is not necessary to add new studies to the meta-analysis in order for Hedges g to reach a value outside the range of ± 0.01. The Duval and Tweedie test shows that excluding the studies that negatively affect the symmetry of the funnel scatter plots for each meta-analysis or adding their exact symmetrical equivalents does not significantly differentiate the calculated effect size. The insignificance of the Egger tests results reveals that there is no publication bias in the meta-analysis study. The results of the analysis indicate the high internal validity of the effect sizes and the adequacy of representing the studies conducted on the relevant subject.

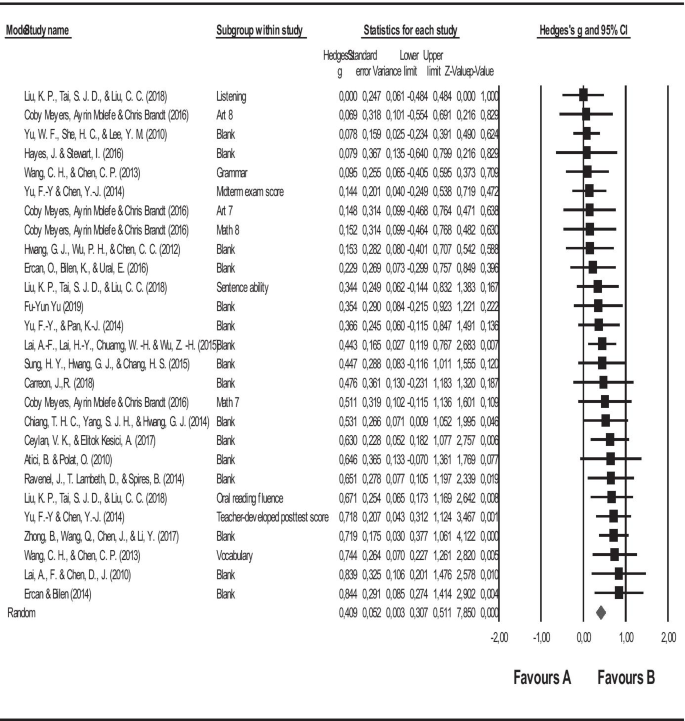

In this study, it was aimed to determine the effect size of online education on academic achievement after testing the publication bias. In line with the first purpose of the study, the forest graph regarding the effect size of online education on academic achievement is shown in Fig. 3 , and the statistics regarding the effect size are given in Table 3 .

The flow chart of the scanning and selection process of the studies

Funnel plot graphics representing the effect size of the effects of online education on academic success

Forest graph related to the effect size of online education on academic success

The square symbols in the forest graph in Fig. 3 represent the effect sizes, while the horizontal lines show the intervals in 95% confidence of the effect sizes, and the diamond symbol shows the overall effect size. When the forest graph is analyzed, it is seen that the lower and upper limits of the combined effect sizes are generally close to each other, and the study loads are similar. This similarity in terms of study loads indicates the similarity of the contribution of the combined studies to the overall effect size.

Figure 3 clearly represents that the study of Liu and others (Liu et al., 2018 ) has the lowest, and the study of Ercan and Bilen ( 2014 ) has the highest effect sizes. The forest graph shows that all the combined studies and the overall effect are positive. Furthermore, it is simply understood from the forest graph in Fig. 3 and the effect size statistics in Table 3 that the results of the meta-analysis study conducted with 27 studies and analyzing the effect of online education on academic achievement illustrate that this relationship is on average level (= 0.409).

After the analysis of the effect size in the study, whether the studies included in the analysis are distributed heterogeneously or not has also been analyzed. The heterogeneity of the combined studies was determined through the Q and I 2 tests. As a result of the heterogeneity test, Q statistical value was calculated as 29.576. With 26 degrees of freedom at 95% significance level in the chi-square table, the critical value is accepted as 38.885. The Q statistical value (29.576) counted in this study is lower than the critical value of 38.885. The I 2 value, which is the complementary of the Q statistics, is 12.100%. This value indicates that the accurate heterogeneity or the total variability that can be attributed to variability between the studies is 12%. Besides, p value is higher than (0.285) p = 0.05. All these values [Q (26) = 29.579, p = 0.285; I2 = 12.100] indicate that there is a homogeneous distribution between the effect sizes, and fixed effects model should be used to interpret these effect sizes. However, some researchers argue that even if the heterogeneity is low, it should be evaluated based on the random effects model (Borenstein et al., 2007 ). Therefore, this study gives information about both models. The heterogeneity of the combined studies has been attempted to be explained with the characteristics of the studies included in the analysis. In this context, the final purpose of the study is to determine the effect of the country, academic level, and year variables on the findings. Accordingly, the statistics regarding the comparison of the stated relations according to the countries where the studies were conducted are given in Table 4 .

As seen in Table 4 , the effect of online education on academic achievement does not differ significantly according to the countries where the studies were conducted in. Q test results indicate the heterogeneity of the relationships between the variables in terms of countries where the studies were conducted in. According to the table, the effect of online education on academic achievement was reported as the highest in other countries, and the lowest in the US. The statistics regarding the comparison of the stated relations according to the class levels are given in Table 5 .

As seen in Table 5 , the effect of online education on academic achievement does not differ according to the class level. However, the effect of online education on academic achievement is the highest in the 4 th class. The statistics regarding the comparison of the stated relations according to the class levels are given in Table 6 .

As seen in Table 6 , the effect of online education on academic achievement does not differ according to the school subjects included in the studies. However, the effect of online education on academic achievement is the highest in ICT subject.

The obtained effect size in the study was formed as a result of the findings attained from primary studies conducted in 7 different countries. In addition, these studies are the ones on different approaches to online education (online learning environments, social networks, blended learning, etc.). In this respect, the results may raise some questions about the validity and generalizability of the results of the study. However, the moderator analyzes, whether for the country variable or for the approaches covered by online education, did not create significant differences in terms of the effect sizes. If significant differences were to occur in terms of effect sizes, we could say that the comparisons we will make by comparing countries under the umbrella of online education would raise doubts in terms of generalizability. Moreover, no study has been found in the literature that is not based on a special approach or does not contain a specific technique conducted under the name of online education alone. For instance, one of the commonly used definitions is blended education which is defined as an educational model in which online education is combined with traditional education method (Colis & Moonen, 2001 ). Similarly, Rasmussen ( 2003 ) defines blended learning as “a distance education method that combines technology (high technology such as television, internet, or low technology such as voice e-mail, conferences) with traditional education and training.” Further, Kerres and Witt (2003) define blended learning as “combining face-to-face learning with technology-assisted learning.” As it is clearly observed, online education, which has a wider scope, includes many approaches.

As seen in Table 7 , the effect of online education on academic achievement does not differ according to online education approaches included in the studies. However, the effect of online education on academic achievement is the highest in Web Based Problem Solving Approach.

4 Conclusions and discussion

Considering the developments during the pandemics, it is thought that the diversity in online education applications as an interdisciplinary pragmatist field will increase, and the learning content and processes will be enriched with the integration of new technologies into online education processes. Another prediction is that more flexible and accessible learning opportunities will be created in online education processes, and in this way, lifelong learning processes will be strengthened. As a result, it is predicted that in the near future, online education and even digital learning with a newer name will turn into the main ground of education instead of being an alternative or having a support function in face-to-face learning. The lessons learned from the early period online learning experience, which was passed with rapid adaptation due to the Covid19 epidemic, will serve to develop this method all over the world, and in the near future, online learning will become the main learning structure through increasing its functionality with the contribution of new technologies and systems. If we look at it from this point of view, there is a necessity to strengthen online education.

In this study, the effect of online learning on academic achievement is at a moderate level. To increase this effect, the implementation of online learning requires support from teachers to prepare learning materials, to design learning appropriately, and to utilize various digital-based media such as websites, software technology and various other tools to support the effectiveness of online learning (Rolisca & Achadiyah, 2014 ). According to research conducted by Rahayu et al. ( 2017 ), it has been proven that the use of various types of software increases the effectiveness and quality of online learning. Implementation of online learning can affect students' ability to adapt to technological developments in that it makes students use various learning resources on the internet to access various types of information, and enables them to get used to performing inquiry learning and active learning (Hart et al., 2019 ; Prestiadi et al., 2019 ). In addition, there may be many reasons for the low level of effect in this study. The moderator variables examined in this study could be a guide in increasing the level of practical effect. However, the effect size did not differ significantly for all moderator variables. Different moderator analyzes can be evaluated in order to increase the level of impact of online education on academic success. If confounding variables that significantly change the effect level are detected, it can be spoken more precisely in order to increase this level. In addition to the technical and financial problems, the level of impact will increase if a few other difficulties are eliminated such as students, lack of interaction with the instructor, response time, and lack of traditional classroom socialization.

In addition, COVID-19 pandemic related social distancing has posed extreme difficulties for all stakeholders to get online as they have to work in time constraints and resource constraints. Adopting the online learning environment is not just a technical issue, it is a pedagogical and instructive challenge as well. Therefore, extensive preparation of teaching materials, curriculum, and assessment is vital in online education. Technology is the delivery tool and requires close cross-collaboration between teaching, content and technology teams (CoSN, 2020 ).

Online education applications have been used for many years. However, it has come to the fore more during the pandemic process. This result of necessity has brought with it the discussion of using online education instead of traditional education methods in the future. However, with this research, it has been revealed that online education applications are moderately effective. The use of online education instead of face-to-face education applications can only be possible with an increase in the level of success. This may have been possible with the experience and knowledge gained during the pandemic process. Therefore, the meta-analysis of experimental studies conducted in the coming years will guide us. In this context, experimental studies using online education applications should be analyzed well. It would be useful to identify variables that can change the level of impacts with different moderators. Moderator analyzes are valuable in meta-analysis studies (for example, the role of moderators in Karl Pearson's typhoid vaccine studies). In this context, each analysis study sheds light on future studies. In meta-analyses to be made about online education, it would be beneficial to go beyond the moderators determined in this study. Thus, the contribution of similar studies to the field will increase more.

The purpose of this study is to determine the effect of online education on academic achievement. In line with this purpose, the studies that analyze the effect of online education approaches on academic achievement have been included in the meta-analysis. The total sample size of the studies included in the meta-analysis is 1772. While the studies included in the meta-analysis were conducted in the US, Taiwan, Turkey, China, Philippines, Ireland, and Georgia, the studies carried out in Europe could not be reached. The reason may be attributed to that there may be more use of quantitative research methods from a positivist perspective in the countries with an American academic tradition. As a result of the study, it was found out that the effect size of online education on academic achievement (g = 0.409) was moderate. In the studies included in the present research, we found that online education approaches were more effective than traditional ones. However, contrary to the present study, the analysis of comparisons between online and traditional education in some studies shows that face-to-face traditional learning is still considered effective compared to online learning (Ahmad et al., 2016 ; Hamdani & Priatna, 2020 ; Wei & Chou, 2020 ). Online education has advantages and disadvantages. The advantages of online learning compared to face-to-face learning in the classroom is the flexibility of learning time in online learning, the learning time does not include a single program, and it can be shaped according to circumstances (Lai et al., 2019 ). The next advantage is the ease of collecting assignments for students, as these can be done without having to talk to the teacher. Despite this, online education has several weaknesses, such as students having difficulty in understanding the material, teachers' inability to control students, and students’ still having difficulty interacting with teachers in case of internet network cuts (Swan, 2007 ). According to Astuti et al ( 2019 ), face-to-face education method is still considered better by students than e-learning because it is easier to understand the material and easier to interact with teachers. The results of the study illustrated that the effect size (g = 0.409) of online education on academic achievement is of medium level. Therefore, the results of the moderator analysis showed that the effect of online education on academic achievement does not differ in terms of country, lecture, class level, and online education approaches variables. After analyzing the literature, several meta-analyses on online education were published (Bernard et al., 2004 ; Machtmes & Asher, 2000 ; Zhao et al., 2005 ). Typically, these meta-analyzes also include the studies of older generation technologies such as audio, video, or satellite transmission. One of the most comprehensive studies on online education was conducted by Bernard et al. ( 2004 ). In this study, 699 independent effect sizes of 232 studies published from 1985 to 2001 were analyzed, and face-to-face education was compared to online education, with respect to success criteria and attitudes of various learners from young children to adults. In this meta-analysis, an overall effect size close to zero was found for the students' achievement (g + = 0.01).

In another meta-analysis study carried out by Zhao et al. ( 2005 ), 98 effect sizes were examined, including 51 studies on online education conducted between 1996 and 2002. According to the study of Bernard et al. ( 2004 ), this meta-analysis focuses on the activities done in online education lectures. As a result of the research, an overall effect size close to zero was found for online education utilizing more than one generation technology for students at different levels. However, the salient point of the meta-analysis study of Zhao et al. is that it takes the average of different types of results used in a study to calculate an overall effect size. This practice is problematic because the factors that develop one type of learner outcome (e.g. learner rehabilitation), particularly course characteristics and practices, may be quite different from those that develop another type of outcome (e.g. learner's achievement), and it may even cause damage to the latter outcome. While mixing the studies with different types of results, this implementation may obscure the relationship between practices and learning.

Some meta-analytical studies have focused on the effectiveness of the new generation distance learning courses accessed through the internet for specific student populations. For instance, Sitzmann and others (Sitzmann et al., 2006 ) reviewed 96 studies published from 1996 to 2005, comparing web-based education of job-related knowledge or skills with face-to-face one. The researchers found that web-based education in general was slightly more effective than face-to-face education, but it is insufficient in terms of applicability ("knowing how to apply"). In addition, Sitzmann et al. ( 2006 ) revealed that Internet-based education has a positive effect on theoretical knowledge in quasi-experimental studies; however, it positively affects face-to-face education in experimental studies performed by random assignment. This moderator analysis emphasizes the need to pay attention to the factors of designs of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The designs of the studies included in this meta-analysis study were ignored. This can be presented as a suggestion to the new studies that will be conducted.

Another meta-analysis study was conducted by Cavanaugh et al. ( 2004 ), in which they focused on online education. In this study on internet-based distance education programs for students under 12 years of age, the researchers combined 116 results from 14 studies published between 1999 and 2004 to calculate an overall effect that was not statistically different from zero. The moderator analysis carried out in this study showed that there was no significant factor affecting the students' success. This meta-analysis used multiple results of the same study, ignoring the fact that different results of the same student would not be independent from each other.

In conclusion, some meta-analytical studies analyzed the consequences of online education for a wide range of students (Bernard et al., 2004 ; Zhao et al., 2005 ), and the effect sizes were generally low in these studies. Furthermore, none of the large-scale meta-analyzes considered the moderators, database quality standards or class levels in the selection of the studies, while some of them just referred to the country and lecture moderators. Advances in internet-based learning tools, the pandemic process, and increasing popularity in different learning contexts have required a precise meta-analysis of students' learning outcomes through online learning. Previous meta-analysis studies were typically based on the studies, involving narrow range of confounding variables. In the present study, common but significant moderators such as class level and lectures during the pandemic process were discussed. For instance, the problems have been experienced especially in terms of eligibility of class levels in online education platforms during the pandemic process. It was found that there is a need to study and make suggestions on whether online education can meet the needs of teachers and students.

Besides, the main forms of online education in the past were to watch the open lectures of famous universities and educational videos of institutions. In addition, online education is mainly a classroom-based teaching implemented by teachers in their own schools during the pandemic period, which is an extension of the original school education. This meta-analysis study will stand as a source to compare the effect size of the online education forms of the past decade with what is done today, and what will be done in the future.

Lastly, the heterogeneity test results of the meta-analysis study display that the effect size does not differ in terms of class level, country, online education approaches, and lecture moderators.

*Studies included in meta-analysis

Ahmad, S., Sumardi, K., & Purnawan, P. (2016). Komparasi Peningkatan Hasil Belajar Antara Pembelajaran Menggunakan Sistem Pembelajaran Online Terpadu Dengan Pembelajaran Klasikal Pada Mata Kuliah Pneumatik Dan Hidrolik. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 2 (2), 286–292.

Article Google Scholar

Ally, M. (2004). Foundations of educational theory for online learning. Theory and Practice of Online Learning, 2 , 15–44. Retrieved on the 11th of September, 2020 from https://eddl.tru.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/01_Anderson_2008-Theory_and_Practice_of_Online_Learning.pdf

Arat, T., & Bakan, Ö. (2011). Uzaktan eğitim ve uygulamaları. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Meslek Yüksek Okulu Dergisi , 14 (1–2), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.29249/selcuksbmyd.540741

Astuti, C. C., Sari, H. M. K., & Azizah, N. L. (2019). Perbandingan Efektifitas Proses Pembelajaran Menggunakan Metode E-Learning dan Konvensional. Proceedings of the ICECRS, 2 (1), 35–40.

*Atici, B., & Polat, O. C. (2010). Influence of the online learning environments and tools on the student achievement and opinions. Educational Research and Reviews, 5 (8), 455–464. Retrieved on the 11th of October, 2020 from https://academicjournals.org/journal/ERR/article-full-text-pdf/4C8DD044180.pdf

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Lou, Y., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Wozney, L., et al. (2004). How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta- analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 3 (74), 379–439. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074003379

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis . Wiley.

Book Google Scholar

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., & Rothstein, H. (2007). Meta-analysis: Fixed effect vs. random effects . UK: Wiley.

Card, N. A. (2011). Applied meta-analysis for social science research: Methodology in the social sciences . Guilford.

Google Scholar

*Carreon, J. R. (2018 ). Facebook as integrated blended learning tool in technology and livelihood education exploratory. Retrieved on the 1st of October, 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1197714.pdf

Cavanaugh, C., Gillan, K. J., Kromrey, J., Hess, M., & Blomeyer, R. (2004). The effects of distance education on K-12 student outcomes: A meta-analysis. Learning Point Associates/North Central Regional Educational Laboratory (NCREL) . Retrieved on the 11th of September, 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED489533.pdf

*Ceylan, V. K., & Elitok Kesici, A. (2017). Effect of blended learning to academic achievement. Journal of Human Sciences, 14 (1), 308. https://doi.org/10.14687/jhs.v14i1.4141

*Chae, S. E., & Shin, J. H. (2016). Tutoring styles that encourage learner satisfaction, academic engagement, and achievement in an online environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(6), 1371–1385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2015.1009472

*Chiang, T. H. C., Yang, S. J. H., & Hwang, G. J. (2014). An augmented reality-based mobile learning system to improve students’ learning achievements and motivations in natural science inquiry activities. Educational Technology and Society, 17 (4), 352–365. Retrieved on the 11th of September, 2020 from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gwo_Jen_Hwang/publication/287529242_An_Augmented_Reality-based_Mobile_Learning_System_to_Improve_Students'_Learning_Achievements_and_Motivations_in_Natural_Science_Inquiry_Activities/links/57198c4808ae30c3f9f2c4ac.pdf

Chiao, H. M., Chen, Y. L., & Huang, W. H. (2018). Examining the usability of an online virtual tour-guiding platform for cultural tourism education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 23 (29–38), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2018.05.002

Chizmar, J. F., & Walbert, M. S. (1999). Web-based learning environments guided by principles of good teaching practice. Journal of Economic Education, 30 (3), 248–264. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183061

Cleophas, T. J., & Zwinderman, A. H. (2017). Modern meta-analysis: Review and update of methodologies . Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55895-0

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Observation. Research Methods in Education, 6 , 396–412. Retrieved on the 11th of September, 2020 from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nabil_Ashraf2/post/How_to_get_surface_potential_Vs_Voltage_curve_from_CV_and_GV_measurements_of_MOS_capacitor/attachment/5ac6033cb53d2f63c3c405b4/AS%3A612011817844736%401522926396219/download/Very+important_C-V+characterization+Lehigh+University+thesis.pdf

Colis, B., & Moonen, J. (2001). Flexible Learning in a Digital World: Experiences and Expectations. Open & Distance Learning Series . Stylus Publishing.

CoSN. (2020). COVID-19 Response: Preparing to Take School Online. CoSN. (2020). COVID-19 Response: Preparing to Take School Online. Retrieved on the 3rd of September, 2021 from https://www.cosn.org/sites/default/files/COVID-19%20Member%20Exclusive_0.pdf

Cumming, G. (2012). Understanding new statistics: Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. New York, USA: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807002

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P. T., & Altman, D. G. (2008). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses . In J. P. T. Higgins & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 243–296). Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184.ch9

Demiralay, R., Bayır, E. A., & Gelibolu, M. F. (2016). Öğrencilerin bireysel yenilikçilik özellikleri ile çevrimiçi öğrenmeye hazır bulunuşlukları ilişkisinin incelenmesi. Eğitim ve Öğretim Araştırmaları Dergisi, 5 (1), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.23891/efdyyu.2017.10

Dinçer, S. (2014). Eğitim bilimlerinde uygulamalı meta-analiz. Pegem Atıf İndeksi, 2014(1), 1–133. https://doi.org/10.14527/pegem.001

*Durak, G., Cankaya, S., Yunkul, E., & Ozturk, G. (2017). The effects of a social learning network on students’ performances and attitudes. European Journal of Education Studies, 3 (3), 312–333. 10.5281/zenodo.292951

*Ercan, O. (2014). Effect of web assisted education supported by six thinking hats on students’ academic achievement in science and technology classes . European Journal of Educational Research, 3 (1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.3.1.9

Ercan, O., & Bilen, K. (2014). Effect of web assisted education supported by six thinking hats on students’ academic achievement in science and technology classes. European Journal of Educational Research, 3 (1), 9–23.

*Ercan, O., Bilen, K., & Ural, E. (2016). “Earth, sun and moon”: Computer assisted instruction in secondary school science - Achievement and attitudes. Issues in Educational Research, 26 (2), 206–224. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.3.1.9

Field, A. P. (2003). The problems in using fixed-effects models of meta-analysis on real-world data. Understanding Statistics, 2 (2), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0202_02

Field, A. P., & Gillett, R. (2010). How to do a meta-analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 63 (3), 665–694. https://doi.org/10.1348/00071010x502733

Geostat. (2019). ‘Share of households with internet access’, National statistics office of Georgia . Retrieved on the 2nd September 2020 from https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/106/information-and-communication-technologies-usage-in-households

*Gwo-Jen, H., Nien-Ting, T., & Xiao-Ming, W. (2018). Creating interactive e-books through learning by design: The impacts of guided peer-feedback on students’ learning achievements and project outcomes in science courses. Journal of Educational Technology & Society., 21 (1), 25–36. Retrieved on the 2nd of October, 2020 https://ae-uploads.uoregon.edu/ISTE/ISTE2019/PROGRAM_SESSION_MODEL/HANDOUTS/112172923/CreatingInteractiveeBooksthroughLearningbyDesignArticle2018.pdf

Hamdani, A. R., & Priatna, A. (2020). Efektifitas implementasi pembelajaran daring (full online) dimasa pandemi Covid-19 pada jenjang Sekolah Dasar di Kabupaten Subang. Didaktik: Jurnal Ilmiah PGSD STKIP Subang, 6 (1), 1–9.

Hart, C. M., Berger, D., Jacob, B., Loeb, S., & Hill, M. (2019). Online learning, offline outcomes: Online course taking and high school student performance. Aera Open, 5(1).

*Hayes, J., & Stewart, I. (2016). Comparing the effects of derived relational training and computer coding on intellectual potential in school-age children. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86 (3), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12114

Horton, W. K. (2000). Designing web-based training: How to teach anyone anything anywhere anytime (Vol. 1). Wiley Publishing.

*Hwang, G. J., Wu, P. H., & Chen, C. C. (2012). An online game approach for improving students’ learning performance in web-based problem-solving activities. Computers and Education, 59 (4), 1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.05.009

*Kert, S. B., Köşkeroğlu Büyükimdat, M., Uzun, A., & Çayiroğlu, B. (2017). Comparing active game-playing scores and academic performances of elementary school students. Education 3–13, 45 (5), 532–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1140800

*Lai, A. F., & Chen, D. J. (2010). Web-based two-tier diagnostic test and remedial learning experiment. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 8 (1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.4018/jdet.2010010103

*Lai, A. F., Lai, H. Y., Chuang W. H., & Wu, Z.H. (2015). Developing a mobile learning management system for outdoors nature science activities based on 5e learning cycle. Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Learning, ICEL. Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) International Conference on e-Learning (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, July 21–24, 2015). Retrieved on the 14th November 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562095.pdf

Lai, C. H., Lin, H. W., Lin, R. M., & Tho, P. D. (2019). Effect of peer interaction among online learning community on learning engagement and achievement. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies (IJDET), 17 (1), 66–77.

Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . Oxford University.

*Liu, K. P., Tai, S. J. D., & Liu, C. C. (2018). Enhancing language learning through creation: the effect of digital storytelling on student learning motivation and performance in a school English course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66 (4), 913–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9592-z

Machtmes, K., & Asher, J. W. (2000). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of telecourses in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 14 (1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640009527043

Makowski, D., Piraux, F., & Brun, F. (2019). From experimental network to meta-analysis: Methods and applications with R for agronomic and environmental sciences. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024_1696-1

* Meyers, C., Molefe, A., & Brandt, C. (2015). The Impact of the" Enhancing Missouri's Instructional Networked Teaching Strategies"(eMINTS) Program on Student Achievement, 21st-Century Skills, and Academic Engagement--Second-Year Results . Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. Retrieved on the 14 th November, 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562508.pdf

OECD. (2020). ‘A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020 ’. https://doi.org/10.26524/royal.37.6

Pecoraro, V. (2018). Appraising evidence . In G. Biondi-Zoccai (Ed.), Diagnostic meta-analysis: A useful tool for clinical decision-making (pp. 99–114). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78966-8_9

Pigott, T. (2012). Advances in meta-analysis . Springer.

Pillay, H. , Irving, K., & Tones, M. (2007). Validation of the diagnostic tool for assessing Tertiary students’ readiness for online learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 26 (2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701310821

Prestiadi, D., Zulkarnain, W., & Sumarsono, R. B. (2019). Visionary leadership in total quality management: efforts to improve the quality of education in the industrial revolution 4.0. In the 4th International Conference on Education and Management (COEMA 2019). Atlantis Press

Poole, D. M. (2000). Student participation in a discussion-oriented online course: a case study. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 33 (2), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/08886504.2000.10782307

Rahayu, F. S., Budiyanto, D., & Palyama, D. (2017). Analisis penerimaan e-learning menggunakan technology acceptance model (Tam)(Studi Kasus: Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta). Jurnal Terapan Teknologi Informasi, 1 (2), 87–98.

Rasmussen, R. C. (2003). The quantity and quality of human interaction in a synchronous blended learning environment . Brigham Young University Press.

*Ravenel, J., T. Lambeth, D., & Spires, B. (2014). Effects of computer-based programs on mathematical achievement scores for fourth-grade students. i-manager’s Journal on School Educational Technology, 10 (1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.26634/jsch.10.1.2830

Rolisca, R. U. C., & Achadiyah, B. N. (2014). Pengembangan media evaluasi pembelajaran dalam bentuk online berbasis e-learning menggunakan software wondershare quiz creator dalam mata pelajaran akuntansi SMA Brawijaya Smart School (BSS). Jurnal Pendidikan Akuntansi Indonesia, 12(2).

Sitzmann, T., Kraiger, K., Stewart, D., & Wisher, R. (2006). The comparative effective- ness of Web-based and classroom instruction: A meta-analysis . Personnel Psychology, 59 (3), 623–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00049.x

Stewart, D. W., & Kamins, M. A. (2001). Developing a coding scheme and coding study reports. In M. W. Lipsey & D. B. Wilson (Eds.), Practical metaanalysis: Applied social research methods series (Vol. 49, pp. 73–90). Sage.

Swan, K. (2007). Research on online learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11 (1), 55–59.

*Sung, H. Y., Hwang, G. J., & Chang, Y. C. (2016). Development of a mobile learning system based on a collaborative problem-posing strategy. Interactive Learning Environments, 24 (3), 456–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2013.867889

Tsagris, M., & Fragkos, K. C. (2018). Meta-analyses of clinical trials versus diagnostic test accuracy studies. In G. Biondi-Zoccai (Ed.), Diagnostic meta-analysis: A useful tool for clinical decision-making (pp. 31–42). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78966-8_4

UNESCO. (2020, Match 13). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Retrieved on the 14 th November 2020 from https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-emergencies/ coronavirus-school-closures

Usta, E. (2011a). The effect of web-based learning environments on attitudes of students regarding computer and internet. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28 (262–269), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.051

Usta, E. (2011b). The examination of online self-regulated learning skills in web-based learning environments in terms of different variables. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 10 (3), 278–286. Retrieved on the 14th November 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ944994.pdf

Vrasidas, C. & MsIsaac, M. S. (2000). Principles of pedagogy and evaluation for web-based learning. Educational Media International, 37 (2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/095239800410405

*Wang, C. H., & Chen, C. P. (2013). Effects of facebook tutoring on learning english as a second language. Proceedings of the International Conference e-Learning 2013, (2009), 135–142. Retrieved on the 15th November 2020 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562299.pdf

Wei, H. C., & Chou, C. (2020). Online learning performance and satisfaction: Do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Education, 41 (1), 48–69.

*Yu, F. Y. (2019). The learning potential of online student-constructed tests with citing peer-generated questions. Interactive Learning Environments, 27 (2), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1458040

*Yu, F. Y., & Chen, Y. J. (2014). Effects of student-generated questions as the source of online drill-and-practice activities on learning . British Journal of Educational Technology, 45 (2), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12036

*Yu, F. Y., & Pan, K. J. (2014). The effects of student question-generation with online prompts on learning. Educational Technology and Society, 17 (3), 267–279. Retrieved on the 15th November 2020 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.565.643&rep=rep1&type=pdf

*Yu, W. F., She, H. C., & Lee, Y. M. (2010). The effects of web-based/non-web-based problem-solving instruction and high/low achievement on students’ problem-solving ability and biology achievement. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 47 (2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703291003718927

Zhao, Y., Lei, J., Yan, B, Lai, C., & Tan, S. (2005). A practical analysis of research on the effectiveness of distance education. Teachers College Record, 107 (8). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2005.00544.x

*Zhong, B., Wang, Q., Chen, J., & Li, Y. (2017). Investigating the period of switching roles in pair programming in a primary school. Educational Technology and Society, 20 (3), 220–233. Retrieved on the 15th November 2020 from https://repository.nie.edu.sg/bitstream/10497/18946/1/ETS-20-3-220.pdf

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Primary Education, Ministry of Turkish National Education, Mersin, Turkey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hakan Ulum .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ulum, H. The effects of online education on academic success: A meta-analysis study. Educ Inf Technol 27 , 429–450 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10740-8

Download citation

Received : 06 December 2020

Accepted : 30 August 2021

Published : 06 September 2021

Issue Date : January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10740-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online education

- Student achievement

- Academic success

- Meta-analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Author Biographies

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Navigating the new normal: adapting online and distance learning in the post-pandemic era.

1. Introduction

1.1. background, 1.2. purpose of the review.

- Highlighting the multifaceted impact of the pandemic on education, including the disruptions caused by school closures and the subsequent shift to remote learning [ 1 ].

- Exploring innovative approaches and strategies employed by educators to ensure effective online teaching and learning experiences [ 2 , 4 ].

- Examining the role of technological solutions and platforms in facilitating remote education and their effectiveness in supporting teaching and learning processes [ 4 ].

- Investigating strategies for promoting student engagement and participation in virtual classrooms, considering the unique challenges and opportunities presented by online and distance learning [ 2 , 3 ].

- Evaluating the various assessment and evaluation methods employed in online education, considering their validity, reliability, and alignment with learning outcomes [ 4 ].

- Discussing the importance of supporting student well-being and academic success in the digital environment, addressing the social and emotional aspects of remote learning [ 3 ].

- Examining the professional development opportunities and resources available for educators to enhance their skills in online teaching and adapt to the changing educational landscape [ 4 ].

- Addressing equity and accessibility considerations in online and distance learning, developing strategies to ensure equitable opportunities for all learners and mitigate the digital divide [ 1 , 2 ].

- Identifying key lessons learned and best practices from the experiences of educators and students during the pandemic, providing insights for future educational practices [ 1 , 4 ].

- Discussing the potential for educational innovation and transformations in teaching and learning practices in the post-pandemic era, considering the lessons learned from the rapid transition to online and distance learning [ 4 ].

1.3. Significance of the Study

- To provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the pandemic on education. UNESCO (2020) reported that the widespread school closures caused by the pandemic disrupted traditional education practices and posed significant challenges for students, educators, and families [ 1 ]. As such, understanding the multifaceted impact of the pandemic is crucial for effective decision making and policy development.

- To highlight innovative approaches to online teaching and learning. Hodges et al. [ 4 ] emphasized the importance of instructional design principles and the use of educational technology tools in facilitating effective online education [ 4 ] by examining strategies employed by educators during the pandemic. This review paper aims to identify successful practices that can be applied in future online and blended learning environments.

- To explore the role of technology in supporting remote education. The rapid transition to online and distance learning has required the use of various technological solutions and platforms. With reference to this subject, Hodges et al. (2020) discussed the difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning, highlighting the importance of leveraging technology to create engaging and interactive virtual classrooms [ 4 ].

- To address equity and accessibility considerations. The pandemic has exacerbated existing inequities in access to education and technology. On this line, UNESCO (2020) emphasized the need to address equity issues and bridge the digital divide to ensure equitable opportunities for all learners. This review paper examines strategies and interventions aimed at promoting equitable access to online and distance learning.

- To provide insights for future educational practices by analyzing experiences, challenges, and successes encountered during the transition to online and distance learning. This review paper aims to provide valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and researchers. So, lessons learned from the pandemic can inform the development of effective educational policies, teacher training programs, and support systems for students.

1.4. Methodology of Search

2. impact of the covid-19 pandemic on education, 3. transitioning from traditional classrooms to online and distance learning, 4. challenges faced by educators during the lockdown period, 5. strategies for effective online teaching and learning, 6. technological solutions and platforms for remote education, 7. promoting student engagement and participation in the virtual classroom, 8. assessments and evaluation methods in online education, 9. supporting student well-being and academic success in the digital environment, 10. professional development for educators in online teaching, 11. addressing equity and accessibility in online and distance learning, 12. lessons learned and best practices for future educational practices, 13. innovations and transformations in education post-pandemic, 14. policy implications and recommendations for effective online education, 15. ethical considerations in online and distance learning, 16. innovations and practical applications in post-pandemic educational strategies.

- Impact Analysis Tools: Develop analytical tools to quantify the educational disruptions caused by the pandemic, focusing on metrics like attendance, engagement, and performance shifts due to remote learning.

- Online Pedagogy Workshops: Create workshops for educators to share and learn innovative online teaching strategies, focusing on interactivity, student-centered learning, and curriculum adaptation for virtual environments.

- Tech-Integration Frameworks: Develop frameworks for integrating and evaluating the effectiveness of various technological solutions in remote education, including LMS, interactive tools, and AI-based learning supports.

- Engagement-Boosting Platforms: Create platforms or tools that specifically target student engagement in virtual classrooms, incorporating gamification, interactive content, and real-time feedback mechanisms.

- Assessment Methodology Guides: Develop guidelines or toolkits for educators to design and implement valid and reliable online assessments aligned with learning outcomes.

- Well-being Monitoring Systems: Implement systems to monitor and support student well-being in digital learning environments, incorporating mental health resources and social-emotional learning components.

- Professional Development Portals: Develop online portals offering continuous professional development opportunities for educators, focusing on upskilling in digital pedagogy, content creation, and adaptive learning technologies.

- Equity and Accessibility Strategies: Formulate and implement strategies to ensure equitable access to online and distance learning, addressing the digital divide through resource distribution, adaptive technologies, and inclusive curriculum design.

- Best Practices Repository: Create a repository of best practices and lessons learned from the pandemic’s educational challenges, serving as a resource for future educational planning and crisis management.

- Post-Pandemic Educational Innovation Labs: Establish innovation labs to explore and pilot new teaching and learning practices in the post-pandemic era, emphasizing the integration of traditional and digital pedagogies.

17. Conclusions: Navigating the Path Forward in Online Education

Author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Reuge, N.; Jenkins, R.; Brossard, M.; Soobrayan, B.; Mizunoya, S.; Ackers, J.; Jones, L.; Taulo, W.G. Education response to COVID 19 pandemic, a special issue proposed by UNICEF: Editorial review. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021 , 87 , 102485. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Yue, X.-G.; McAleer, M. Risk Management of COVID-19 by Universities in China. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020 , 13 , 36. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bao, W. COVID-19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020 , 2 , 113–115. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning ; Educause: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bashir, A.; Bashir, S.; Rana, K.; Lambert, P.; Vernallis, A. Post-COVID-19 Adaptations; the Shifts towards Online Learning, Hybrid Course Delivery and the Implications for Biosciences Courses in the Higher Education Setting. Front. Educ. 2021 , 6 , 310. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Akpa, V.O.; Akinosi, J.R.; Nwankwere, I.A.; Makinde, G.O.; Ajike, E.O. Strategic Innovation, Digital Dexterity and Service Quality of Selected Quoted Deposit Money Banks in Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2022 , 10 , 15–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020 , 59 , 1218–1239.e3. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Van Lancker, W.; Parolin, Z. COVID-19, School Closures, and Child Poverty: A Social Crisis in the Making. Lancet Public Health 2020 , 5 , e243–e244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020 , 395 , 912–920. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Pretorius, T.B. Teacher Burnout in the Time of COVID-19: Antecedents and Psychological Consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023 , 20 , 4204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Al Lily, A.E.; Ismail, A.F.; Abunasser, F.M.; Alhajhoj Alqahtani, R.H. Distance Education as a Response to Pandemics: Coronavirus and Arab Culture. Technol. Soc. 2020 , 63 , 101317. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Means, B.; Toyama, Y.; Murphy, R.; Bakia, M.; Jones, K. Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies ; Centre for Learning Technology: Hong Kong, China, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Picciano, A.G. Theories and Frameworks for Online Education: Seeking an Integrated Model. In A Guide to Administering Distance Learning ; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 79–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burgstahler, S.E.; Cory, R.C. Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice ; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicol, D.J.; Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative Assessment and Self-regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2006 , 31 , 199–218. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Stodel, E.J.; Thompson, T.L.; MacDonald, C.J. Learners’ Perspectives on What Is Missing from Online Learning: Interpretations through the Community of Inquiry Framework. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2006 , 7 , 1–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Richardson, J.C.; Maeda, Y.; Lv, J.; Caskurlu, S. Social Presence in Relation to Students’ Satisfaction and Learning in the Online Environment: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017 , 71 , 402–417. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mayer, R.E. Using Multimedia for E-learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2017 , 33 , 403–423. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Swan, K. Building Learning Communities in Online Courses: The Importance of Interaction. Educ. Commun. Inf. 2002 , 2 , 23–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sato, S.N.; Condes Moreno, E.; Villanueva, A.R.; Orquera Miranda, P.; Chiarella, P.; Bermudez, G.; Aguilera, J.F.T.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychological Impacts of Teaching Models on Ibero-American Educators during COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2023 , 13 , 957. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dennen, V.P.; Burner, K.J. The Cognitive Apprenticeship Model in Educational Practice. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology ; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008; pp. 425–439. [ Google Scholar ]