Here are some more reasons why liberal arts matter

Associate Professor of History, Assistant Dean of Faculty for Pre-Major Advising, Dartmouth College

Disclosure statement

Cecilia Gaposchkin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Lately, in the heated call for greater STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) education at every level, the traditional liberal arts have been needlessly, indeed recklessly, portrayed as the villain. And STEM fields have been (falsely) portrayed as the very opposite of the liberal arts.

The detractors of the liberal arts (who usually mean, by liberal arts, “humanities”) tend to argue that STEM-based education trains for careers while non-STEM training does not; they are often suspicious of the liberal political agenda of some disciplines. And they deem the content of a liberal arts education to be no longer relevant. The author of a recent article simply titled, “ The Liberal Arts are Dead; Long Live STEM conveyed this sentiment when he said, "Science is better for society than the arts.”

I see this misunderstanding even at my own institution, as a humanist who oversees pre-major advising and thus engages with students and faculty (and parents) from all over the university. The idea that STEM is something separate and different than the liberal arts is damaging to both the sciences and their sister disciplines in the humanities and social sciences.

Pro-STEM attitudes assume that the liberal arts are quaint, impractical, often elitist, and always self-indulgent, while STEM fields are practical, technical, and represent at once “the future” and “proper earning potential.”

STEM is part of liberal arts

First, let’s be clear: This is a false and misleading dichotomy. STEM disciplines are a part of the liberal arts. Math and science are liberal arts.

In the ancient and medieval world, when the liberal arts as we know them began to take shape, they comprised grammar, logic, rhetoric, music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy (the last three we would count as STEM disciplines today; and music, dealing mostly with numerical relationships through sound, was really more akin to what we would today call physics).

Advocates of STEM are missing the point. The value of a liberal arts education is not in the content that is taught, but rather in the mode of teaching and in the intellectual skills that are gained by learning how to think systematically and rigorously.

These intellectual skills include how to assess assumptions; develop strategies from problem solving; test ideas against evidence; use reason to grapple with information to come to new conclusions; and develop courses of action to pursue those conclusions.

Yes, some disciplines might prepare for certain types of problem solving (how do I get a computer to integrate information from two different consumer data platforms in the most elegant fashion?) more strongly than others (what do I recommend to investors based upon my French-language research of markets in Madagascar?).

And some areas of knowledge might be more useful than others in certain industries.

But in all cases, the point of the liberal arts approach is to learn how to think, not simply what to know – especially since information itself is now so easily acquired through Google and the smartphone. If anything, content is too abundant for any single individual to master. What is much more important is knowing what on Earth to do with the glut of information available in most situations.

And here is where the liberal arts training comes in.

A liberal arts education (STEM-based or otherwise) is not just about learning content, but about knowing how to sort through ambiguity; work with inexact or incomplete information, evaluate contexts and advance a conclusion or course of action.

In other words, it is not about learning the prescription to achieve a textbook result. It is about having the intellectual capacity to attack those issues for which there is yet no metaphorical text or answer.

Is liberal arts the choice of the elite?

Now, let us take up the elephant in the room. Many people would argue an engineering degree balanced with some English courses might be a nice idea.

But for a student to major in English or studio art is sheer craziness. What does one do with a studio art degree except become a starving artist? What does one do with an English degree except wait tables?

Those who make such arguments usually conflate “liberal arts” with “humanities,” those disciplines that do not have an obvious “end career goal” or a “remuneration outcome” at the other side of the college degree.

When detractors hear educators like me say that “the liberal arts” are valuable, they understand us to mean that they fulfill something in the core of our souls. That is, that the humanities are personally and intellectually valuable, but not remuneratively so.

They hear us acknowledge that the humanities are decidedly not practical, and are thus are the purview of the elite and privileged who can afford to indulge in them. But, of course, the idea that the only remunerative professions out there are in science and technology is silly.

Whole industries do in fact exist that are not based on STEM premises: media, consulting, fashion, finance, publishing, education, government and other forms of public service are just a few.

And even those reputedly “tech” industries that STEM advocates see as our future (IT, health, energy) require all sorts of nontechnical employees to get their companies to work.

Further, basic communication, speaking and writing skills are absolute must-haves of anyone who is going to climb the ladder in any high-tech industry .

What defines success

That said, the so-called “practical” major (and I reject the designation) might have a more obvious, path to the entry level job of a solid career. This is only because the major has an apparently known professional pathway.

But that does not guarantee success in that field.

In fact, those other disciplines that detractors of the liberal arts (read: humanities) assume are dead ends could well be fantastic springboards to amazing professional lives.

They are not a guarantee of one – and neither is a STEM degree . But they give those students who have committed seriously to the study of excelling within their college discipline (be it classics, anthropology, or theoretical physics) the capacity and the ability to achieve one.

Some people talk about this as critical thinking; some as the ability to think outside of the box; some as “transferability” – the ability to carry critical intellectual skills from one challenge or industry to another.

In my view, done right, liberal education makes one smarter and more able to be successful and innovative on the path one embarks on. And although we can all point to exceptions (would that Bill Gates had graduated from college!), for the most part, it is those who know how to think nimbly, creatively and responsibly that end up building extraordinary careers.

Why we need a liberal arts education

Let us return to my earlier point about STEM disciplines.

We should not only accept that they are part of a liberal arts education, but we must understand that teaching them within a liberal arts framework makes the financial investment of learning them of greater value.

Peter Robbie , an engineering professor at Dartmouth College who teaches human centered design, explains why liberal education is so critical to engineering training. He said in an email to me that:

creative design process of engineering provides the means for complex, multidisciplinary problem-solving. We need to educate leaders who can solve the ‘wicked problems’ facing society (like obesity, climate change, and inequality). These are multifactorial problems that can’t be solved within a single domain but will need liberally-educated, expansive thinkers who are comfortable in many fields.

As we know, an engineer who has basic cultural competency skills (honed, for instance, through cultural studies) will be an attractive asset for an American engineering firm trying to branch out in China.

Likewise, a doctor who knows how to listen to patients will be a better primary care doctor than one who only knows the memorizable facts from medical school. This is one reason that medical schools have recently changed the requirements of application to encourage coursework in sociology and psychology.

It is the ability to use these skills honed by different types of thinking in various contexts that allows people to build beyond their particular ken.

And that is what a liberal arts education – science, technology, humanities and social sciences – trains. It prepares students for rich, creative, meaningful and, yes, remunerative, careers.

- Mathematics

- Critical thinking

- remuneration

- Liberal arts

- Engineering degree

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 190,200 academics and researchers from 5,047 institutions.

Register now

The Life-Shaping Power of Higher Education

By Marvin Krislov

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

As I begin my first full semester as president of Pace University after serving for 10 years as president of Oberlin College, I find myself looking to the past and the things I’ve learned. I can’t help but reflect on the extraordinary changes I’ve witnessed in American higher education along the way.

This past decade has been one of transformation for our nation and our colleges and universities. Barack Obama was twice elected president of the United States. We experienced the Great Recession -- the worst economic downturn since the Depression. Income inequality has grown from a significant problem to a polarizing divide, with ripples felt in every corner of our society. The internet has become the newswire of the world and the center of our economic might, as well as a battlefield where terror is waged and democracy is tested.

Same-sex marriage has moved from limited recognition in a few states to the boldly embraced law of the land. Rather than evolving into a postracial society, we’ve realized we have a long, long way to go. And after a bare-knuckle election that splintered families and friendships, Donald Trump was elected president of our not so United States. In the words of the Grateful Dead, “What a long, strange trip it’s been.”

American higher education has also been on a journey. There have been many changes and challenges during my time as a college president. But one important thing hasn’t changed: the value of a college education and its ability to transform students’ lives.

That life-shaping power sometimes gets overlooked in the shifting landscape of higher education. Colleges and universities are facing an array of economic, demographic and sociopolitical challenges. Among the most significant is the public’s changing perception of the purpose and value of a college education. The short version: many Americans think a college degree should be a ticket to a specific job -- the cheaper the ticket, the better.

Campus climate issues have also changed dramatically since 2007. While many small residential colleges exist in a kind of bubble, many of those climate issues mirror what is happening in our society. Race is one example. The realization of a postracial society has not been achieved, and the nation has seen race become a much more contentious issue. The killings of unarmed black men by police officers spawned the Black Lives Matter movement and fueled student activism on campuses across the country. The hatred and bigotry displayed in Charlottesville, Va., undoubtedly will spark difficult conversations and more this fall.

Ensuring free speech is another campus issue that has grown more challenging over the past decade. In the classrooms and on campuses, getting students to discuss difficult issues freely and respectfully remains a challenge.

Of course, no reference to free speech is complete without also acknowledging the mechanism by which it is exercised. Social media and technology have been a decidedly mixed blessing in promoting civil discourse. Read the comments section on just about any news story having to do with one of America’s top liberal arts schools, and you’ll find no shortage of trolls and vitriolic anti-intellectualism.

Yet one thing hasn’t changed: the value of a liberal arts education. I received an outstanding liberal arts education as an undergraduate, and it continues to shape my career and my life. I firmly believe liberal education is the best preparation a young person can have for the job market and a rewarding, meaningful life as a citizen of our democracy.

Continuing the Great Conversation

Today, however, liberal education finds itself under fire more often than in the past. The primary reason for this -- to borrow a phrase from the movie Cool Hand Luke -- is a failure to communicate. Many colleges and universities that embrace liberal education suffer from a certain degree of self-satisfaction. We know our graduates do well in their lives and careers. We celebrate that within our own communities. But as a group we don’t do an effective job of communicating that success to the broader public. We need to better explain what liberal education is. We need to better articulate what we do -- and why it is so important for our country and the world.

That said, the value of liberal arts education can be hard to convey because it can’t be boiled down to a simple sound bite or an eye-popping starting salary. The mission of most liberal arts colleges is to educate the whole person rather than training graduates to succeed at specific jobs. Robert Maynard Hutchins, the great American educator who studied at Oberlin College and Yale University and served for decades as president of the University of Chicago, wrote in a famous essay on education titled “The Great Conversation” that the aim of liberal education is human excellence both private and public -- meaning excellence as a person and as a member of society.

Liberal education does that by teaching students to become lifelong learners who are their own best teachers. It enables them to take intellectual risks and to think laterally -- to understand how the humanities, the arts and the sciences inform, enrich and affect one another. By connecting diverse ideas and themes across the academic disciplines, liberal arts students learn to better reason and analyze, and express their creativity and their ideas.

College should do more than get you one job. It should prepare you to succeed in multiple careers. Studies show that current college graduates will likely change careers a dozen times in their lives -- and do so before turning 40. If all they learned in college was how to do one thing well, navigating those changes is going to be tough.

Successful careers and financial gain are just part of the value of a liberal arts education. Its true worth is measured not in dollars but in meaningful lives well lived. Through the years, the breadth, depth, flexibility and rigor of American liberal arts education has enriched countless lives in myriad ways. It has also produced many leaders in virtually every field of human endeavor. Other countries are now embracing the liberal arts in a bid to create employees who are not rigid technocrats but more flexible and innovative thinkers.

Given the global leadership of American higher education, and the global economy’s demands for flexible, adaptable employees, undergraduate liberal education is more than relevant. It remains one of our country’s great assets.

Is it for everyone? Of course not. But for those who pursue liberal arts education, it can be life transforming.

I see this life-transforming potential across all types of colleges and universities. Some people might consider Pace University an unusual next step for someone who spent a decade as president of a small, semi-rural school in a Midwestern state. Yet while Oberlin and Pace are vastly different institutions, they hold equally impressive records and embrace certain common values and concentrations of study -- and both provide an important liberal arts education.

Despite its modest size, Oberlin College has never had difficulty distinguishing itself from much larger, more recognizable metropolitan peers. It was established nearly 200 years ago with an abolitionist philosophy that challenged the conventional thinking of the time. It would become the oldest coed liberal arts college in the nation and the first to admit students of all races. It would see its first African-American graduate become the first black lawyer admitted to the bar in the state of New York and play an integral role in the early years of Howard University.

Oberlin continues to embrace a progressive legacy. Its campus community is known for its diversity and inclusion, its advocacy of LGBTQ issues, and its social and political activism. In addition, the college has distinguished itself for a commitment to arts and culture through the extremely selective Oberlin Conservatory of Music. It was also an early proponent of study in sustainability and effective environmental stewardship.

With a total enrollment of 13,000 students across three campuses, Pace is significantly larger than Oberlin. Its students hail from all 50 states and 109 countries around the world. Two-thirds study at the university’s flagship location, a textbook metropolitan center in lower Manhattan, while the rest opt for its Pleasantville and White Plains campuses in Westchester County to the north.

Long regarded as a commuter accounting school, the university now offers over 100 majors and degree programs and encompasses six schools, including a law school consistently ranked third in the nation for its environmental law program, plus ultracompetitive undergraduate and graduate performing arts programs.

Despite their differences, diversity and gender equality are hallmarks of student populations at both Oberlin and Pace. Pace, like Oberlin, was ahead of its time and admitted women and minorities from the beginning, in 1906. Today, nearly two-thirds of students are women and more than half self-identify as a minority. Unlike at Oberlin, many Pace students are the first in their families to go to college. And while income is just one outcome by which to measure the value of a college education, a study by the Equality of Opportunity Project ranks Pace first in New York -- and second in the nation -- for economic mobility based on students who enter college at the bottom fifth of income distribution and end up in the top fifth.

That’s just another example of the life-transforming potential of the liberal arts. I am inspired and energized by the changes I have witnessed in American higher education over the past 10 years. As I look to the future as president of Pace University, I am excited by the promise and possibility of things to come and the impact the university will have on the lives of current and future generations of students.

The past decade is proof that higher education is more relevant and essential to our modern world than ever before -- and the value of a college degree has never been greater than it is today. Providing access to such an education for any student who wishes to pursue it strikes me as a goal that any great nation should and must embrace.

The End of the Academy?

Share this article, more from views.

It’s Past Time to Allow Paid Field Placements

Professional schools should allow students to make money while earning credit, Neha Lall writes.

Inside Higher Ed Names Newsroom Leadership Team

As Inside Higher Ed approaches its 20th birthday, our newsroom has new leaders steadfast in their commitment

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

The Value of a Liberal Arts Education is More Than Most Know

Columns appearing on the service and this webpage represent the views of the authors, not of The University of Texas at Austin.

“What are you going to do with that?” Many new graduates will hear this question in the coming weeks.

For a business or computer science graduate, the answers seem obvious. What about someone studying a liberal arts field, like English or history or philosophy? A common misconception sees these as useless subjects or a waste of valuable resources. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Given the skills employers want, the traits we need in the next generation of leaders, and the qualities we value in our neighbors and friends, we might well ask the liberal arts grad, “What can’t you do with that?”

The main concern people have about liberal arts is marketability. Where are the jobs for people studying ancient Greek or African history? Everywhere. Because what those students are learning, alongside verb forms and dates, are the skills that appear time and again on top of employers’ wish lists. Skills such as persuasion, collaboration and creativity.

Does this mean that a liberal arts degree is as financially lucrative as computer science or petroleum engineering? No. But liberal arts majors do just fine in the workplace. Liberal arts students go on to earn good livings in a wide variety of fields, including technology.

In fact, the median annual income of a liberal arts major is just 8% lower than the median for all majors and more than one-third higher than the median income of people without a college degree.

Liberal arts offer not just financial value, but also personal, social and cultural values. The liberal arts take their name from the Latin word “liber,” which means “free.” Originally this referred to the education of free persons as distinct from slaves, but freedom is still at the root of the liberal arts. Liberal arts are a privilege of a free society, and the study of the liberal arts helps to keep us free.

Why is this? Contrary to what some would have us believe, our financial and social well-being depends on how we respond to the kinds of open-ended questions that liberal arts fields are asking. A computer scientist wants to invent a cool new app or technology. Whether he does a good job is measured by how much money his product earns.

As we see all too often, little thought is given to the social effects of these new technologies. They cause serious harm that people trained in writing computer code and making money may be unable or unwilling to address. Earnings can’t measure the things that most of us really care about when we think about new technologies.

This is where the liberal arts come in. The bedrock of a liberal arts education is the ability to understand a complex situation from many different viewpoints. To understand that the same information may look different to different people, or even to the same person at different times. We need the liberal arts to address questions that have no one right answer. And most of the important questions facing society are questions like this.

For instance, with all the technologies revolutionizing our society, how should we balance the need for accurate news and information with individual free speech? Where is the line between a legitimate business use of personal data and exploitation? Who gets to decide? So far, technology companies have done a lousy job of grappling with these questions. Some history majors, with their rich understanding of how complex forces shape society over time, would be a great idea.

Such skills have value in lots of places besides the workplace. The philosophy major on the church executive board is thinking about how the bedrock values of his community should inform decisions about replacing the roof or hiring a new Sunday school teacher. The English major participating in an environmental advocacy group can use her rhetorical and analytical skills to narrow the gap between the near-unanimous scientific consensus on climate change and political inaction on the issue.

The mistaken view that liberal arts are not financially valuable creates the more damaging idea that some fields of study have financial value, while others have social values. With liberal arts, we get both. Our society depends on it.

Deborah Beck is an associate professor of classics at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in The Hill .

Explore Latest Articles

Sep 19, 2024

UT Continues To Achieve All-Time Highs in Applications, Enrollment and Graduation Rates

Sep 18, 2024

President Hartzell Emphasizes Talent and Broadens Definition of Student Success in State of the University Address

New AI Institute Led by UT Researchers Will Accelerate Cosmic Discovery

- Skip to main content

Life & Letters Magazine

The Value of the Liberal Arts

By Hina Azam September 20, 2022 facebook twitter email

Those of us who teach in liberal arts colleges are passionate about the value of a liberal arts education. But for those outside of academia – even for those who might have received a degree in UT’s College of Liberal Arts – the precise meaning of “liberal arts” can be murky. What, exactly, is meant by the “liberal arts”? What is the history of the idea, and how does it translate into the educational concept we know as a “liberal-arts curriculum,” or, more broadly, a “liberal education”? What is the value of a liberal arts education to both individual and collective life? This essay presents a brief overview of the idea, history, purposes, and values of liberal arts education, so that you, our readers, may understand the passion that inspires our faculty’s teaching and scholarship, and be similarly inspired.

What are the Liberal Arts?

The idea of the liberal arts originates in ancient Greece and was further developed in medieval Europe. Classically understood, it combined the four studies of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music – known as the quadrivium – with the three additional studies of grammar, rhetoric, and logic – known as the trivium . These artes liberales were meant to teach both general knowledge and intellectual skills, and thus train the mind. This training of the mind as well as this foundational body of content knowledge and intellectual skills was regarded by scholars and educators as necessary for all human beings – and especially a society’s leaders – in order to live well, both individually and collectively.

These liberal arts were distinguished from vocational or clinical arts, such as law, medicine, engineering, and business. These latter were conceived as servile arts – i.e. arts that served concrete production or construction. These productive/constructive arts were also known as artes mechanicae , “mechanical arts,” which included crafts such as weaving, agriculture, masonry, warfare, trade, cooking, and metallurgy. In contrast to the vocational or mechanical arts, the liberal arts put greater weight on intellectual skills – the ability to think and communicate clearly, and to analyze and solve problems. But more distinctively, the liberal arts emphasized learning and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, independent of immediate application. The liberal arts taught not only bodies of knowledge, but – more dynamically – how to go about finding and creating knowledge – that is, how to learn. Finally, the liberal arts taught not only how to think and do, but also how to be – with others and with oneself, in the natural world and the social world. They were thus centrally concerned with ethics.

Notably, the term “liberal arts” has nothing to do with liberalism in the contemporary political or partisan sense; the opposite of “liberal” here is not “conservative.” Rather, the term goes back to the Latin root signifying “freedom,” as opposed to imprisonment or subjugation. Think here of the English word “liberty.” The liberal arts were historically connected to freedom in that they encompassed the types of knowledge and skills appropriate to free people, living in a free society. The term “art” in this phrase also must be understood correctly, for it does not refer to “art” as we use it today in its creative sense, to denote the fine and performing arts. Rather, from the Latin root ars , “art” is here used to refer to skill or craft. The “liberal arts,” then, may be thought of as liberating knowledges, or alternatively, the skills of being free.

What is a Liberal Arts Education ?

A liberal (arts) education is a curriculum designed around imparting core knowledge and skills through engagement with a wide range of subjects and disciplines. This core knowledge is taught through general education courses typically drawn from the humanities, (creative) arts, natural sciences, and social sciences. The humanities include disciplines such as language, literature, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy, religion, history, law, geography, archaeology, anthropology, politics, and classics. Natural sciences include subjects such as geology, chemistry, physics, and life sciences such as biology. Social sciences comprise disciplines such as sociology, economics, linguistics, psychology, and education. Through a core curriculum or general education courses, students gain a basic knowledge of the physical and natural world as well as of human ideas, histories, and practices.

A liberal arts education comprises more than learning only content, but also honing skills and cultivating values. Intellectual and practical skills at the heart of the liberal arts are reading comprehension, inquiry and analysis, critical and creative thinking, written and oral communication, information and quantitative literacy, teamwork and problem-solving. Values that are central to liberal education are personal and social responsibility, civic knowledge and engagement, intercultural knowledge and competence, ethical reasoning and action, and lifelong learning.

Why a Liberal Education? Purposes and Values

Four overarching purposes anchor the idea of an education in the liberal arts. One of those is liberty . As mentioned above, the traditional idea of the liberal arts was an education that befitted a free person, one who was fit to participate freely in the life of society. The modern casting of this idea is that a broad education does not limit one to a particular profession or occupation, but rather, is meant for any life path – it prepares the mind for a variety of possible futures and for constructive participation in a civil democratic society. The interconnection between liberal education and human freedom cannot be over-emphasized, and it was at the forefront of the minds of the great political theorists and educators of the western tradition. Those with insufficient knowledge and skills would easily fall prey to demagogues and agents of chaos, and pervasive ignorance and lack of intellectual skill would eat away at a polity’s foundations. Only an informed citizenry – who had familiarity with and foundational understanding in the major areas of knowledge, and who had the requisite skills to both process existing information and seek out reliable new information – would be able to uphold and maintain a democratic society and stave off a decline into tyranny and despotism. As Thomas Jefferson, a major architect of the American public university, held, “Wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government.” [1]

Another central purpose of a liberal arts education is the inculcation of the principle of human worth. This purpose is built on values collectively known as humanism : the idea that human life, individual and collective, has intrinsic value; the idea that human beings are endowed with rights to life, liberty, property, and a number of other rights that we know as “human rights”; that human beings are fundamentally equal, even if they are not the same, and that that equality should translate into both political and legal equality. This ideal of humanism is not in opposition to religious beliefs and practices; however, it regards the public sphere as one in which all should be able to participate regardless of religious beliefs and practices. Humanism mirrors the principle of a common or shared humanity, even while recognizing differences of experience, perspective, and resources. This vision is at the heart of that facet of liberal arts known as the humanities . Writes Robert Thornett, “Humanities is, in fact, education in how to be a human being.” [2] A liberal arts education exposes learners to diverse types of knowledge – which allow for understanding and empathy with others – within a humanistic framework that aims for deeper unity and synthesis. This approach to knowledge serves as a bulwark against social, political and ideological forces that seek to drive wedges between human beings, and that all too often culminate in violence and oppression.

A third purpose of liberal education is to provide a space for contemplation of truth and virtue , based on the conviction that such contemplation is necessary for the free mind, and that informed explorations of these notions lead to the formation of better human beings. The liberal arts are where students have opportunity to consider the “big questions”: What is true? What is good? What is just? What is beautiful? This contemplation is what fires the imaginations of our students, and what makes the liberal arts curriculum unlike any other curriculum. Vartan Gregorian explains the unique character of liberal arts education, writing that “the deep-seated yearning for knowledge and understanding endemic to human beings is an ideal that a liberal arts education is singularly suited to fulfill.” [3]

A fourth value of liberal arts education is its emphasis on the skills of learning , and of constructing knowledge out of information. We live in an increasingly complex information environment, where the sheer quantity of information – and its intentional manipulation into disinformation – overwhelms people’s abilities to make sense of it all. Without sufficient training, people are less equipped to find reliable information, to understand what they encounter, and to process that information, mentally and emotionally, into rational knowledge that can form the basis of ethical evaluation and action . This is a matter of grave importance for all human beings – in their capacity as students, citizens, consumers, workers, and people in relationships. Gregorian long ago identified the problem of information overload, and the function of education, in an interview with Bill Moyers: “Unfortunately, the information explosion … does not equal knowledge. … So, we’re facing a major problem: how to structure information into knowledge. Because … there are great possibilities of manipulating our society by inundating us with undigested information… paralyzing our choices by giving so much that we cannot possibly digest it.” [4]

Given this paralyzing deluge of information, he continues, “The teaching profession, the universities, have to provide connections … connections between subjects, connections between disciplines … to provide some kind of intellectual coherence.” In the final analysis, suggests Gregorian, “Education’s sole function is now, possibly, [to] provide an introduction to learning.”

The purposes and values outlined above cannot easily be fulfilled outside of an intentional liberal arts curriculum. One does meet people who are driven to read widely and to pursue lifelong learning; to develop skills of information critique and lucid oral and written communication; to hold steadily to the vision of a shared humanity and humane ethical conduct; to undertake the ethical burden of preserving political liberties and civil rights; to engage in sustained contemplation of truth and practice of virtue; to perceive the interconnectedness of different spheres of knowledge and therefore of our world; and to develop the facility to synthesize chaotic data and irrational information into rational and cogent knowledge. But these goals are far more difficult to achieve outside of the structured, collective, and compulsory activities of the college classroom and away from teachers whose minds are perpetually set to these concerns. For too many, such integrated learning is out of reach or undervalued. Meanwhile, the insufficient attainment and integration of broad knowledge, intellectual skills, and ethical reflection is wreaking havoc on our society and national culture; on our quality of life morally, intellectually, psychologically, and physically; and finally, on our planet, which is increasingly unable to withstand humanity’s relentless onslaught and is fast losing the capacity to sustain its assailant.

Liberal-arts education is not found in any one course, classroom, or teacher. It is a composite formation, attained over time through series of courses and learning opportunities that together coalesce in the minds of students. Each instructor, and each course, contributes elements that are oriented toward the purposes identified above. It is through the process of seeing the interconnections between different areas of knowledge, using diverse intellectual skills, that the human mind gains the capacity for liberation.

[1] https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/genesis-university-virginia

[2] Robert Thornett, “What Are College Students Paying For?” at The Quillette , June 2, 2022 [ https://quillette.com/2022/06/02/what-are-college-students-paying-for-the-stephen-curry-effect-and-getting-back-to-basics/

[3] Historian and former Brown University President Vartan Gregorian, in his essay “American Higher Education: An Obligation to the Future” at https://higheredreporter.carnegie.org/introduction/ .

[4] “Vartan Gregorian: Living in the Information Age,” interview with Bill Moyers, at https://billmoyers.com/content/vartan-gregorian/ .

The Unexpected Value of the Liberal Arts

First-generation students are finding personal and professional fulfillment in the humanities and social sciences.

Growing up in Southern California, Mai-Ling Garcia’s grades were ragged; her long-term plans nonexistent. At age 20, she was living with her in-laws halfway between Los Angeles and the Mojave Desert, while her husband was stationed abroad. Tired of working subsistence jobs, she decided in 2001 to try a few classes at Mount San Jacinto community college.

Nobody pegged her for greatness at first. A psychology professor, Maria Lopez-Moreno recalls Garcia sitting in the midst of a lecture hall, fiddling constantly with a cream-colored scarf. Then something started to catch. After a spirited discussion about the basis for criminal behavior, Lopez-Moreno took this newcomer aside after class and asked: “Why are you here?”

Garcia blurted out a tangled story of marrying a Marine right after high school, seeing him head off to Iraq, and not knowing what to do next. Lopez-Moreno couldn’t walk away. “I said to myself: ‘Uh-oh. I’ve got to suggest something to her.’” At her professor’s urging, Garcia applied for a place in Mt. San Jacinto’s honors program—and began to thrive.

Nourished by smaller classes and motivated peers, Garcia earned straight-A grades for the first time. She emerged as a leader in diversity initiatives, too, drawing on her own multicultural heritage (Filipino and Irish). Shortly before graduation, she won admission to the University of California, Berkeley, campus, where she could pursue a bachelor’s degree.

Today, Garcia is a leading digital strategist for the city of Oakland, California. Rather than rely on an M.B.A. or a technical major, she has capitalized on a seldom-appreciated liberal-arts discipline—sociology—to power her career forward. Now, she describes herself as a “bureaucratic ninja” who doesn’t hide her stormy journey. Instead, she recognizes it as a valuable asset.

“I know what it’s like to be too poor to own a computer,” Garcia told me recently. “I’m the one in meetings who asks: ‘Never mind how well this new app works on an iPhone. Will it run on an old, public-library computer, because that’s the only way some of our residents will get to use it?’”

By its very name, the liberal-arts pathway is tinged with privilege. Blame this on Cicero, the ancient Roman orator, who championed the arts quae libero sunt dignae ( cerebral studies suited for freemen), as opposed to the practical, servile arts suited for lower-class tradespeople. Even today, liberal-arts majors in the humanities and social sciences often are portrayed as pursuing elitist specialties that only affluent, well-connected students can afford.

Look more closely, though, and this old stereotype is starting to crumble. In 2016, the National Association of Colleges and Employers surveyed 5,013 graduating seniors about their family backgrounds and academic paths. The students most likely to major in the humanities or social sciences—33.8 percent of them—were those who were the first generation in their family ever to have earned college degrees. By contrast, students whose parents or other forbears had completed college chose the humanities or social sciences 30.4 percent of the time.

Pursuing the liberal-arts track isn’t a quick path to riches. First-job salaries tend to be lower than what’s available with vocational degrees in fields such as nursing, accounting, or computer science. That’s especially true for first-generation students, who aren’t as likely to enjoy family-aided access to top employers. NACE found that first-generation students on average received post-graduation starting salaries of $43,320, about 12 percent below the pay packages being landed by peers with multiple generations of college experience.

Yet over time, liberal-arts graduates’ earnings often surge, especially for students pursuing advanced degrees. History majors often become well-paid lawyers or judges after completing law degrees, a recent analysis by the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project has found. Many philosophy majors put their analytical and argumentative skills to work on Wall Street. International-relations majors thrive as overseas executives for big corporations, and so on.

For college leaders, the liberal arts’ appeal across the socioeconomic spectrum is both exciting and daunting. As Dan Porterfield, the president of Pennsylvania’s Franklin and Marshall College, points out, first-generation students “may come to college thinking: ‘I want to be a doctor. I want to help people.’ Then they discover anthropology, earth sciences, and many other new fields. They start to fall in love with the idea of being a writer or an entrepreneur. They realize: ‘I just didn’t have a broad enough vision of how to be a difference maker in society.’”

A close look at the career trajectories of liberal-arts graduates highlights five factors—beyond traditional classroom academics—that can spur long-term success for anyone from a non-elite background. Strong support from a faculty mentor is a powerful early propellant. In a survey of about 1,000 college graduates, Richard Detweiler, president of the Great Lakes Colleges Association, found that students who sought out faculty mentors were nearly twice as likely to end up in leadership positions later in life.

Other positive factors include a commitment to keep learning after college; a willingness to move to major U.S. job hubs such as Seattle, Silicon Valley, or the greater Washington, D.C., area; and the audacity to dream big. Finally, students who enter college without well-connected relatives—the sorts who can tell you what classes to take or how to win a choice summer internship—benefit from programs designed to build up professional networks and social capital.

Among the groups offering career-readiness programs on campus is Braven, a nonprofit founded by Aimée Eubanks Davis, a former Teach for America executive. Making its debut in 2014, Braven already has reached about 1,000 students at Rutgers University-Newark in New Jersey and San Jose State University in California. Expansion into the Midwest is on tap. Braven mixes students majoring in the liberal arts and those pursuing vocational degrees in each cohort, the theory being that all can learn from one another.

One of Braven’s Newark enrollees in 2015 was Dyllan Brown-Bramble, a transfer student earning strong grades in psychology, who didn’t feel at all connected to the New Jersey campus. Commuting from his parents’ home, he usually arrived at Rutgers just a few minutes before 10 a.m. classes started. Once afternoon courses were done, he’d retreat to Parking Lot B and rev up his 2003 Sentra. By 3:50 p.m., he’d be gone.

Brown-Bramble’s parents are immigrants from Dominica. His father runs a small construction business; his mother, a Baruch College graduate, manages a tourism office. Privately, the Rutgers student is quite proud of them, but it seemed pointless to explain his Caribbean origins to strangers. They typically reacted inappropriately. Some imagined him to be the son of dirt-poor refugees struggling to rise above a shabby past. Others assumed he was a world-class genius: “an astrophysicist who could fly.” There wasn’t any room for him to be himself.

When Brown-Bramble encountered a campus flier urging students to enroll in small evening workshops called the Braven Career Accelerator, he took the bait. “I knew I was supposed to be networking in college,” he later told me. “I thought: Okay, here’s a chance to do something.”

Suddenly, Rutgers became more compelling. For nine weeks, Brown-Bramble and four other students of color became evening allies. They met in an empty classroom each Tuesday at six to construct LinkedIn profiles and practice mock interviews. They picked up tips about local internships, aided by a volunteer coach whose life and background was much like theirs. They united as a group, discussing each person’s weekly highs and lows while encouraging one another to keep trying for internships and better grades. “We had a saying,” Brown-Bramble recalled. “If one of us succeeds, all of us succeed.”

Most of the volunteer coaches came from minority backgrounds, too. Among them: Josmar Tejeda, who had graduated from the New Jersey Institute of Technology five years earlier with an architecture degree. Since graduating, Tejeda had worked at everything from social-media jobs to being an asbestos inspector. As the coach for Brown-Bramble’s group, Tejeda combined relentless optimism with an acknowledgment that getting ahead wasn’t easy.

“Keep it real,” Tejeda kept telling his students as they talked through case studies and their own goals. Everyone did so. That feeling of being the only black or Latino person in the room? The awkwardness of always being asked: Where are you from? The strains of always trying to be the “model minority”? Familiar territory for everyone.

“It was liberating,” Brown-Bramble told me. Surrounded by sympathetic peers, Brown-Bramble discovered new ways to share his heritage in job interviews. Yes, some of his Caribbean relatives had arrived in the United States not knowing how to fill out government forms. As a boy, he had needed to help them. But that was all right. In fact, it was a hidden strength. “I could create a culture story that worked for me,” Brown-Bramble said. “I can relate to people with different backgrounds. There’s nothing about me that I have to rise above.”

This summer, with the support of Inroads , a nonprofit that promotes workforce diversity, Brown-Bramble is interning in the compliance department of Novo Nordisk, a pharmaceutical maker. Riding the strength of a 3.8 grade-point average, he plans to get a law degree and work in a corporate setting for a few years to pay off his student loans. Then he hopes to set up his own law firm, specializing in start-up formation. “I’d like to help other entrepreneurs do things in Newark,” he told me.

Organizations like Braven draw on “the power of the cohort,” said Shirley Collado, the president of Ithaca College and a former top administrator at Rutgers-Newark. When students settle into small groups with trustworthy peers, she explained, candor takes hold. The sterile dynamic of large lectures and solo homework assignments gives way to a motivation-boosting alliance among seat mates and coaches. “You build social capital where it didn’t exist before,” Collado said.

For Mai-Ling Garcia, the leap from community college to Berkeley was perilous. Arriving at the famous university’s campus, she and her then-husband were so short on cash that they subsisted most days on bowls of ramen. Scraping by on partial scholarships, neither knew how to get the maximum available financial aid. To cover expenses, Garcia took a part-time job teaching art at a grade-school recreation center in Oakland.

Finishing college can become impossible in such circumstances. During her second semester, Garcia began tracking down what she now refers to as “a series of odd little foundations with funky scholarships.” People wanted to help her. Before long, she was attending Berkeley on a full ride. Her money problems abated. What she couldn’t forget was that initial feeling of being in trouble and ill-prepared. Her travails were pulling her into sociology’s most pressing issues: how vulnerable people fare in a world they don’t understand, and what can be done to improve their lives.

Simultaneously, Berkeley’s professors were arming Garcia with tools that would define her career. She spent a year learning the fine points of ethnography from a Vietnam-era Marine, Martin Sanchez-Jankowski, who taught students how to conduct field research. He sent Garcia into the Oakland courthouse to watch judges in action, advising her to heed the ways racial differences tinged courtroom conduct. She learned to take careful notes, to be explicit about her theories and assumptions, and to operate with a rigor that could withstand peer-review scrutiny. Her professors would stay in academia; she was being trained to have an impact in the wider world.

What can one do with a sociology degree? Garcia tried a lot of different jobs in her first few years after graduation. She spent two years at a nonprofit trying to untangle Veterans Administration bureaucracy. After that, she dedicated three years to a position at the Department of Labor, winning many small battles related to veterans’ employment. She had found job security, but she couldn’t shake the feeling that a technology revolution was racing through the private sector—and leaving government far behind.

Companies like Lyft, Airbnb, and Instagram were putting new powers in the public’s hands, giving them handy tools to hail a ride, find lodging, or share photos. By comparison, trying to change a jury-duty date remained a clumsy slog through outdated websites. Instead of bemoaning this tech gap, Garcia decided to gain vital tech skills herself. She signed up for evening classes in digital marketing and refined that knowledge during an 18-month stint at a startup. Then she began hunting for a government job with impact.

In 2014, Garcia joined the City of Oakland as a bridge builder who could amp up online government services on behalf of the city’s 400,000 residents. This wasn’t just an exercise in technology upgrading; it required a fundamental rethinking of the way that Oakland delivered services. Buffers between city workers and an impatient public would come down. The social structures of power would change. To make this transition, it helped to have a digitally savvy sociologist in the house.

Over coffee one afternoon, Garcia told me excitedly about the progress that she and the city communications manager were achieving with their initiative. If street-art creators want more recognition for their work, Garcia can drum up interest on social media. If garbage is piling up, new digital tools let citizens visit the city’s Facebook page and summon services within seconds.

Looking ahead, Garcia envisions a day when landing a municipal job becomes vastly easier, with cities’ Twitter feeds posting each new opening. Other aspects of digital technology ought to help residents connect quickly with whatever part of government matters to them—whether that means signing up for summer camp or giving the mayor a piece of one’s mind.

Related Video

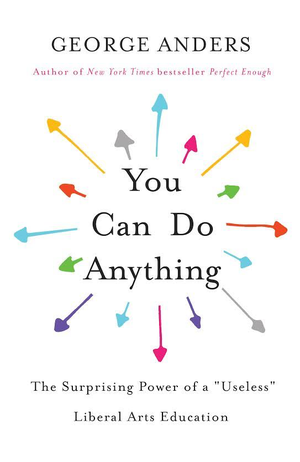

This article has been adapted from George Anders’s new book, You Can Do Anything.

About the Author

Why Liberal Arts?

Permission to Hope

Welcome back to the weather channel! For today’s forecast, we predict high wind speeds, freezing temperatures, a 99% chance of precipitation… uh, yes, altogether a gloomy week ahead in the land of Higher Education. With the looming threat of volatile post-pandemic labor markets, students are scrambling to hold onto any semblance of stability.

In the face of sweeping change, humans tend to seek shelter in the pragmatics, tossing hopes and dreams aside for formulaic predictors of success (or heck, survival). This phenomenon manifests not only in students, but also in the scholarly discourse around the plight of higher education. I’m talking, in particular, about the proponents of the liberal arts—a pedagogy that seems to be less defined by what exactly it is, but what exactly it isn’t: a technical education that trains young adults for a specific profession. Think not of pre-med tracks, trade schools, and vocational programs, but of a holistic undergraduate experience that exposes students to a breadth of intellectual disciplines. One such proponent, Martha Nussbaum, a prescient thinker in philosophy and academia at the University of Chicago, assigns a liberal arts education the purpose of “liberating the mind from the bondage of habit and custom” (38). Her work centers on the preservation of democracy through the instruction of the classical humanities, which uniquely equips graduates with the superpower to remain skeptics of authority, transcend a self-centered worldview, and approach others with empathy (38-40). But again, this rhetoric of pragmatics persists. By Nussbaum’s logic, the liberal arts is not that different from a technical education in its intention: both prepare young adults to be active participants of society, whether broadly as citizens or more narrowly as employees. One just does so more discretely by one-sidedly lauding the humanities, a presently more “useless” field.

But wait. Why should we concede so early that students should regard their education solely in terms of its practical utility? Aren’t we still telling students what they should do, rendering them beholden to external authorities, rather than asking them what they want to do? Timothy Burke, curiously, a history professor at a top liberal arts college, speaks to the absurdity of the argument that students must willfully adapt to the ever-changing demands of the powers that be. In his timely article, “An Unconvincing Argument for the Liberal Arts,” he questions whether the liberal arts even prepares students to weather the pandemic storms—a foregone conclusion for many of its advocates—and, crucially, whether it should. On the former point, he cautions against a reductive caricature of vocational education, which may be the only financially viable path for many, and highlights COVID-19 as testament that coping with uncertainty has more to do with socioeconomic privilege than with the extolled virtues of “‘resilience,’ ‘emotional intelligence,’ or ‘grit’” (5). On the latter point, Burke hints at a much more deep-seated, unnatural trend: “uncertainty [is] engineered on purpose… to produce insecurity and precarity for the benefit of a few” (6). To fill in the subject for the passive-voice phrase, he singles out “the oligarchs of the present American moment” (7) keen on puppeteering the labor markets for a quick buck. For him, we should be actively educating students to wholly reject any form of “unwarranted benediction” (8) and loyalty to that corrupt elite class.

I’m taking his argument one step further. Not only do the capitalist oligarchs engineer uncertainty, they engineer hopelessness under the crushing pressure of that uncertainty, all while enlisting the help of schools, teachers, and parents to push students to fall in line. And how do I know that? Because hopelessness infuses the very fabric of my experience in college thus far—at a liberal arts institution, at that—manifesting in the tiny side remarks among peers that can only be met with an awkward silence:

“In an ideal world where my parents weren’t chemists and the world wasn’t going to shit, I’d want to be a radio talk show host. But…”

In this paper, I’ve charged myself with the rather challenging goal of providing a satisfying answer to this heartbreaking comment.

Coming from an elite Bay Area STEM private high school (woah what a mouthful), I had become painfully aware of how early people start with the “but,” automatically subscribing to a path of rigid, impersonal career training. Among peers pumped chock-full of SAT prep and (nepotistic) internships since sixth grade, I had always felt insane for taking two arts electives a year and treating summers as mental health breaks. In some perverted, perhaps self-sabotaging attempt to “not be like other Harker students,” I disavowed most of the Ivies and set search for a small liberal arts college.

And by the luck of the draw, I ended up at Dartmouth—the best of both worlds, as far away as possible from my old world. Since my biggest fear was boxing myself into a specialized future, my biggest criterion was a school that actively encouraged exploration and flexibility. My rationale: only with exposure to all the available areas of study can I, myself, make a rational decision to focus on one. Thus, building upon Burke’s insights as well as my personal experience, I argue that the exclusive value of a liberal arts education (done right) comes not from its inclusion of the “arts,” but from the “liberal” structure of its host institution. By giving young people back the power of choice and agency, the liberal arts uniquely renews hope, the rainbows-and-unicorns notion that a better future is out there, despite all odds . But hope operates on one key condition: you must do the work of reimagining the future in terms of what you want and what you are capable of changing. It’s a slow, arduous process only possible with a confidence that there is always more to learn and always a personal and societal value to learn. This metric of a student’s love of learning, then, becomes the ultimate litmus test for the success of a liberal arts institution.

Qualifying Nussbaum’s definition of “liberal,” I see “liberating the mind” as less about thinking for yourself and more about choosing for yourself. For me, the liberal arts means plopping students into a free-ranging intellectual playground that celebrates all kinds of learning, empowering students self-select purposes they find worthwhile. Here, I would be remiss not to highlight John Dewey, the pioneer of modern educational philosophy. While he predominantly catered to primary school educators as his audience, his work on experiential learning rings harmoniously with my discussion of the liberal arts in higher education. In chapter five of Education and Experience , “The Nature of Freedom,” Dewey hones in on the importance of a classroom that facilitates intellectual freedom. By eliminating a culture of rigid rule-following and restricted movement, educators can fabricate a healthy social dynamic that prompts “free play for individuality of experience” (58).

While, luckily, we rarely witness such disciplinarian environments in the classroom today, more clandestine forms of social control endure. Prior to college, many teens—soiled by the many adults whispering in their ears—do not have this privilege of “free play,” as evidenced by my peers at Harker. Perhaps, what distinguishes the liberal arts from a vocational education is not the perception of how much agency a young adult deserves to have, but how much they truly and verifiably have. A vocational education prescribes that you must have already figured out what to do with your life by junior year in high school, failing to consider whether that decision is fully yours to begin with. I behoove you to ask yourself: to what extent did your dream college, major, job at sixteen align with your dreams “in an ideal world”? For the friend I cited earlier, it clearly did not; she herself admitted defeat to the will of her parents. And after all, before I explored my soft spot for philosophy and public policy, I was pre-med to the core. (That was more a function of Grey’s Anatomy than parental pressure, but you get the gist.)

If you could look at my first-year course load now, you wouldn’t leave with any cohesive story. Calculus, Public Policy, Computer Science, Acting, Psychology all appear as disparate disciplines, but that’s precisely intentional: Dartmouth’s liberal arts structure affords me the opportunity to extract my favorite flavors from each to concoct my own little personalized, nuanced intellectual hotpot. Though it somewhat pains me to acknowledge, such a liberal fabric may be more thorny in practice, however. Who’s to say that after escaping Harker, I didn’t subconsciously latch onto a new external control at Dartmouth? Dewey would concur that freedom is not an end in itself, but a means to developing a capacity for self-control through an intensive reevaluation of the self (61). When you don’t stay faithful to your authentic, internal impulses and let them inform your educational decisions, “it is easy to jump out of the frying-pan into the fire” (64). One such fire-lined pitfall may be Dartmouth’s distributive requirements—the very quality that makes the institution liberal arts, some might argue. For students with preordained academic goals, is taking distributive-fulfilling courses sufficient in instilling curiosity if there was none to begin with? For those already poised to use college to explore, does making intellectual breadth required invalidate or override the intrinsic value of learning those disciplines?

Perhaps contradicting Dewey’s emphasis on self-control, the new form of authority may very well originate from within, as a product of an inundating culture of maximizing achievement. Just mastering one subject isn’t enough, you must master them all. William Deresiewicz, former Yale English professor and author of Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite , provides copious first-hand accounts of this mindless box-checking, a narrative borne out of the admissions officer’s paragon of the “well-lopsided” (51) student who excels at everything. He quotes a student: “Yale students… are like stem cells. They can be anything in the world, so they try to delay for as long as possible the moment when they have to become just one thing in particular. Possibility, paradoxically, becomes limitation” (27-28). Curiously, the expectation of possibility can itself become so crippling that it undermines the value of a liberal arts curriculum. And make no mistake: this possibility has little to do with hope. The students who learn horizontally may only do so because they can or they have to , not necessarily because they want to . Once again, exploration has been reduced down to a practical exercise of hopelessly pandering to an external authority, whether the admissions officer or the employer.

So how do we reframe the purpose of the liberal arts to teach students to use their newfound agency to nurture their own interests and passions? We must radically reinstate the importance of instant gratification, the temptation to forgo a long-term benefit to enjoy a short-term reward. According to psychology, the ability to delay gratification predicts higher levels of achievement and self-worth later down the line (Gazzaniga 226). But also according to psychology, our reward center—the nucleus accumbens—develops before our rational decision-maker—the frontal lobe—in order to get us out into the world and make dumb mistakes in our youthful years when the consequences are still tame (213). Our brains don’t want us to always plan ahead. Like I alluded to earlier, this notion of harnessing your fleeting impulses goes hand-in-hand with Dewey’s idea of a progressive pedagogy. While the traditional educational approach seeks to keep our beastly instincts in check by imposing discipline in the classroom, the progressive educational approach assumes that humans are born with innate capacities that should be nurtured through experience (12). Dewey further contends, “only by extracting at each present time the full meaning of each present experience are we prepared for doing the same thing in the future” (49). More important than preparing students for (certain) uncertainty, the challenge of an effective liberal arts education—aptly positioned at the tender transitional stage from youth to adulthood—lies in teaching students to maximize each passing moment and transfer that skill into the real world. Only then can students carefully and intentionally mold their impulses into purpose.

Yet, as evidenced throughout this paper, young adults are now taking delayed gratification to new heights, rowing upstream against their psychology to train themselves for survival. If this sounds depressing, it is. Delayed gratification is the very antithesis of hope. It asserts that enjoying the present moment is a wasteful investment, because you should rather expend your energy on x, y, z things that feel required by society, like conducting first-year research, graduating summa cum laude , and climbing the corporate ladder. It inextricably implies sacrifice, but that’s not what they tell you when you sign up to be an adult.

Deresiewicz exhorted that “if you find yourself to be the same person at the end of college as you were at the beginning… Go back and do it again” (101). I say: if you come out of formal schooling believing you have nothing left to learn, go back and do it again. Forfeiting a love of learning suggests a loss of not only self-efficacy, but also an outward-looking societal efficacy—the belief that your knowledge and actions can fix the problems you see in the world and that the world itself is worth fixing. Instant gratification, then, is the permission to hope. It’s the encouraging shoulder squeeze that tells you, hey, that thing you’ve tossed aside as useless, it’s exactly what you need right now . You deserve to manifest your “ideal world.”

But even I can’t respond to my friend that way with full confidence. Such a rose-colored view of the future soothes the ears, but fails to soothe the soul. I previously brought up, almost as a passing comment, Burke’s point about privilege as a predictor of who survives the storm. From here, another question arises: should we even hope, when not everyone can afford to hope? I would answer that with another, perhaps more despairing proposition: the moment we concede that hope is misplaced or irrational should be a massive wake-up call to the deep-rooted inequities of our educational system. We have managed to excommunicate hope into an “ideal world” only some of us can easily access.

At least for me, in my next three-and-a-half years at Dartmouth, I’m juicing every last drop of my privileged right to choose. I’m choosing hope because the opposite means raising a white flag to the powerful incentive systems that toil to keep us hopeless. Now begins the harder work of granting everyone not only the permission to hope, but also the vocabulary to use it effectively. But that’s a problem much bigger than the liberal arts, even in its uniquely youth-empowering design, can begin to tackle.

Works Cited

Burke, Timothy. “An Unconvincing Argument for the Liberal Arts.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 9 July 2021, https://www.chronicle.com/article/an-unconvincing-argument-for-the-liberal-arts.

Deresiewicz, William. Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life. , 2014. Print.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan, 1963. Print.

Gazzaniga, Michael S, Todd F. Heatherton, and Diane F. Halpern. Psychological Science . New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2010. Print.

Nussbaum, Martha. Cultivating Humanity and World Citizenship. , Future Forum 37, 2007.

Wilson Quarterly

Wilson Quarterly Archives

- Current Issue

Search form

Why the liberal arts still matter.

Never has a broad liberal education been more necessary than it is today, and never have colleges and universities done such a poor job of delivering it. Radical measures are needed.

Everyone is in favor of liberal education. Praise of its benefits is found in countless university commencement addresses and reports by commissions on higher education. But it seems that nobody can agree on what liberal education is.

For some, liberal education means a general education, as opposed to specialized training for a particular career. For others, it refers to a subject matter—“the humanities” or “the liberal arts.” Still others think of liberal education in terms of “the classics” or “the great books.”

All of these conceptions of liberal education are right—but each is only partly right. The tradition of liberal education in Europe and the Americas is a synthesis of several elements. Three of these have already been mentioned: nonspecialized general education; an emphasis on a particular set of scholarly disciplines, the humanities; and acquaintance with a canon of classics. The traditional Western synthesis included two other important elements: training in rhetoric and logic, and the study of the languages in which the classics and commentary on them were written (Greek and Latin, and, in the case of Scripture, Hebrew as well).

What brought all of these different elements together in the liberal education model was their purpose: training citizens for public life, whether as rulers or voters. Liberal education is, first and foremost, training for citizenship. The idea of a liberal education as a “gentleman’s education” reflects the fact that, until recent generations, citizenship was restricted in practice if not law to a rich minority of the population in republics and constitutional monarchies. In a democratic republic with universal suffrage, the ideal—difficult as it may be to realize—is a liberal education for all citizens.

Liberal education, in different versions, formed the basis of Western higher education from the Renaissance recovery of Greco-Roman culture to the late 19th century. In the last century, however, liberal education as the basis for higher education in the United States and other nations has been almost completely demolished by opposing forces, the most important of which is utilitarianism, with its demand that universities be centers of practical professional training. So completely has the tradition been defeated that most of the defenders of liberal education do not fully understand what they are defending.

The first thing that must be said about liberal education is that the word “liberal” is misleading. In this context, “liberal” has nothing to do with political liberalism, or “liberation of the mind” (a false etymology that is sometimes given by people who should know better).

“Liberal arts” is a translation of the Latin term artes liberales. Artes means crafts or skills, and liberales comes from liber, or free man, an individual who is both politically free, as a citizen with rights, and economically independent, as a member of a wealthy leisure class. In other words, “liberal arts” originally meant something like “skills of the citizen elite” or “skills of the ruling class.” Cicero contrasted the artes quae libero sunt dignae (arts worthy of a free man) with the artes serviles, the servile arts or lower-class trades. As the Renaissance humanist Pier Paolo Vergerio wrote in “The Character and Studies Befitting a Free-Born Youth” (1402–03), “We will call those studies liberal, then, which are worthy of a free man.”

Once “liberal arts” is understood in its original sense as “elite skills,” then the usefulness of elements of a traditional liberal arts education for a ruling elite becomes apparent:

Classical languages. In the last 200 years, as the study of Greek and Latin declined, its proponents often argued that learning these two languages was valuable in itself, or that it provided “mental discipline.” But such far-fetched arguments were unnecessary for nearly two millennia. In their day, the relatively unsophisticated Romans needed to read and understand Greek in order to read most of what was worth reading on subjects from philosophy, medicine, and military tactics to astronomy and agriculture. Greek was also the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean, shared by the Romans with their subjects. Subsequent generations of Europeans and Americans learned Latin and, sometimes, Greek for equally practical reasons.

Rhetoric and logic. The members of the ruling class—whether they were citizens in democratic Athens or republican Rome, or courtiers in a monarchy—were expected to debate issues of public policy. The Greeks and Romans naturally emphasized rhetoric and logic. Rhetoric helped you persuade the voters or the king, while logic permitted you to rip your opponent’s arguments to shreds.

Beginning with Plato, philosophers and theologians often railed against rhetoric as the seductive art of prettifying falsehood. In modern, democratic societies, rhetoric is often equated with bombast—“mere rhetoric.” But the great theorists of rhetoric, from the Athenian Isocrates to the Romans Cicero and Quintilian, insisted that their ideal was the moral and patriotic citizen, and manuals of rhetoric subordinated flowery language to clarity of thought.

General education. On hearing his son Alexander play the flute, King Philip of Macedon is reported to have asked, “My son, have you not learned to play the flute too well?” A governing elite, whether in a republic, a monarchy, or a dictatorship, must know a lot about many subjects but not too much about any particular subject. An aristocrat or general should show some accomplishment in arts such as poetry, scholarship, music, and sports, but only as an amateur, not a professional. Even in modern democracies, the same logic applies. U.S. senators and presidents must know enough to be well informed about many subjects, from global warming to military strategy to Federal Reserve policy. But a senator or president who neglected other issues while devoting too much time to studying one favorite subject would be guilty of dereliction of duty.

A focus on the humanities. While the liberally educated elite could master the basics of any subject, subjects in the the humanities or liberal arts were of particular importance in the education of rulers, in republics and autocracies alike. Studies in these areas, according to Romans such as Cicero and Seneca, helped an individual cultivate humanitas, by which is meant not humanitarianism (although education might promote understanding of others), but rather the higher, uniquely “human” faculties of the mind and character, as opposed to the lower faculties needed by peasants and craftsmen, those human beasts of burden (once again, the class bias of the liberal arts tradition is evident).

In the Middle Ages, the “seven liberal arts” came to be thought of as the trivium (grammar, dialectic or logic, and rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy)—in essence, literacy and numeracy. Renaissance humanists, rebelling against the logic chopping they associated with medieval Christian Scholasticism, downgraded the mathematical subjects in favor of their own list of the “humanities,” including grammar, rhetoric, politics, history, and ethics. Mathematics, however, survived as part of the liberal arts curriculum in the West until the 19th century.