- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Journal of Molecular Cell Biology

- Society affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Obesity: causes, consequences, treatments, and challenges.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Obesity: causes, consequences, treatments, and challenges, Journal of Molecular Cell Biology , Volume 13, Issue 7, July 2021, Pages 463–465, https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjab056

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Obesity has become a global epidemic and is one of today’s most public health problems worldwide. Obesity poses a major risk for a variety of serious diseases including diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic liver disease (NAFLD), cardiovascular disease, hypertension and stroke, and certain forms of cancer ( Bluher, 2019 ).

Obesity is mainly caused by imbalanced energy intake and expenditure due to a sedentary lifestyle coupled with overnutrition. Excess nutrients are stored in adipose tissue (AT) in the form of triglycerides, which will be utilized as nutrients by other tissues through lipolysis under nutrient deficit conditions. There are two major types of AT, white AT (WAT) and brown AT, the latter is a specialized form of fat depot that participates in non-shivering thermogenesis through lipid oxidation-mediated heat generation. While WAT has been historically considered merely an energy reservoir, this fat depot is now well known to function as an endocrine organ that produces and secretes various hormones, cytokines, and metabolites (termed as adipokines) to control systemic energy balance. Studies over the past decade also show that WAT, especially subcutaneous WAT, could undergo ‘beiging’ remodeling in response to environmental or hormonal perturbation. In the first paper of this special issue, Cheong and Xu (2021) systematically review the recent progress on the factors, pathways, and mechanisms that regulate the intercellular and inter-organ crosstalks in the beiging of WAT. A critical but still not fully addressed issue in the adipose research field is the origin of the beige cells. Although beige adipocytes are known to have distinct cellular origins from brown and while adipocytes, it remains unclear on whether the cells are from pre-existing mature white adipocytes through a transdifferentiation process or from de novo differentiation of precursor cells. AT is a heterogeneous tissue composed of not only adipocytes but also nonadipocyte cell populations, including fibroblasts, as well as endothelial, blood, stromal, and adipocyte precursor cells ( Ruan, 2020 ). The authors examined evidence to show that heterogeneity contributes to different browning capacities among fat depots and even within the same depot. The local microenvironment in WAT, which is dynamically and coordinately controlled by inputs from the heterogeneous cell types, plays a critical role in the beige adipogenesis process. The authors also examined key regulators of the AT microenvironment, including vascularization, the sympathetic nerve system, immune cells, peptide hormones, exosomes, and gut microbiota-derived metabolites. Given that increasing beige fat function enhances energy expenditure and consequently reduces body weight gain, identification and characterization of novel regulators and understanding their mechanisms of action in the beiging process has a therapeutic potential to combat obesity and its associated diseases. However, as noticed by the authors, most of the current pre-clinical research on ‘beiging’ are done in rodent models, which may not represent the exact phenomenon in humans ( Cheong and Xu, 2021 ). Thus, further investigations will be needed to translate the findings from bench to clinic.

While both social–environmental factors and genetic preposition have been recognized to play important roles in obesity epidemic, Gao et al. (2021) present evidence showing that epigenetic changes may be a key factor to explain interindividual differences in obesity. The authors examined data on the function of DNA methylation in regulating the expression of key genes involved in metabolism. They also summarize the roles of histone modifications as well as various RNAs such as microRNAs, long noncoding RNAs, and circular RNAs in regulating metabolic gene expression in metabolic organs in response to environmental cues. Lastly, the authors discuss the effect of lifestyle modification and therapeutic agents on epigenetic regulation of energy homeostasis. Understanding the mechanisms by which lifestyles such as diet and exercise modulate the expression and function of epigenetic factors in metabolism should be essential for developing novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity and its associated metabolic diseases.

A major consequence of obesity is type 2 diabetes, a chronic disease that occurs when body cannot use and produce insulin effectively. Diabetes profoundly and adversely affects the vasculature, leading to various cardiovascular-related diseases such as atherosclerosis, arteriosclerotic, and microvascular diseases, which have been recognized as the most common causes of death in people with diabetes ( Cho et al., 2018 ). Love et al. (2021) systematically review the roles and regulation of endothelial insulin resistance in diabetes complications, focusing mainly on vascular dysfunction. The authors review the vasoprotective functions and the mechanisms of action of endothelial insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling pathways. They also examined the contribution and impart of endothelial insulin resistance to diabetes complications from both biochemical and physiological perspectives and evaluated the beneficial roles of many of the medications currently used for T2D treatment in vascular management, including metformin, thiazolidinediones, glucagon-like receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors, as well as exercise. The authors present evidence to suggest that sex differences and racial/ethnic disparities contribute significantly to vascular dysfunction in the setting of diabetes. Lastly, the authors raise a number of very important questions with regard to the role and connection of endothelial insulin resistance to metabolic dysfunction in other major metabolic organs/tissues and suggest several insightful directions in this area for future investigation.

Following on from the theme of obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction, Xia et al. (2021) review the latest progresses on the role of membrane-type I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), a zinc-dependent endopeptidase that proteolytically cleaves extracellular matrix components and non-matrix proteins, in lipid metabolism. The authors examined data on the transcriptional and post-translational modification regulation of MT1-MMP gene expression and function. They also present evidence showing that the functions of MT1-MMP in lipid metabolism are cell specific as it may either promote or suppress inflammation and atherosclerosis depending on its presence in distinct cells. MT1-MMP appears to exert a complex role in obesity for that the molecule delays the progression of early obesity but exacerbates obesity at the advanced stage. Because inhibition of MT1-MMP can potentially lower the circulating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and reduce the risk of cancer metastasis and atherosclerosis, the protein has been viewed as a very promising therapeutic target. However, challenges remain in developing MT1-MMP-based therapies due to the tissue-specific roles of MT1-MMP and the lack of specific inhibitors for this molecule. Further investigations are needed to address these questions and to develop MT1-MMP-based therapeutic interventions.

Lastly, Huang et al. (2021) present new findings on a critical role of puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PSA), an integral non-transmembrane enzyme that catalyzes the cleavage of amino acids near the N-terminus of polypeptides, in NAFLD. NAFLD, ranging from simple nonalcoholic fatty liver to the more aggressive subtype nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, has now become the leading chronic liver disease worldwide ( Loomba et al., 2021 ). At present, no effective drugs are available for NAFLD management in the clinic mainly due to the lack of a complete understanding of the mechanisms underlying the disease progress, reinforcing the urgent need to identify and validate novel targets and to elucidate their mechanisms of action in NAFLD development and pathogenesis. Huang et al. (2021) found that PSA expression levels were greatly reduced in the livers of obese mouse models and that the decreased PSA expression correlated with the progression of NAFLD in humans. They also found that PSA levels were negatively correlated with triglyceride accumulation in cultured hepatocytes and in the liver of ob/ob mice. Moreover, PSA suppresses steatosis by promoting lipogenesis and attenuating fatty acid β-oxidation in hepatocytes and protects oxidative stress and lipid overload in the liver by activating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, the master regulator of antioxidant response. These studies identify PSA as a pivotal regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism and suggest that PSA may be a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for treating NAFLD.

In summary, papers in this issue review our current knowledge on the causes, consequences, and interventions of obesity and its associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disease ( Cheong and Xu, 2021 ; Gao et al., 2021 ; Love et al., 2021 ). Potential targets for the treatment of dyslipidemia and NAFLD are also discussed, as exemplified by MT1-MMP and PSA ( Huang et al., 2021 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). It is noted that despite enormous effect, few pharmacological interventions are currently available in the clinic to effectively treat obesity. In addition, while enhancing energy expenditure by browning/beiging of WAT has been demonstrated as a promising alternative approach to alleviate obesity in rodent models, it remains to be determined on whether such WAT reprogramming is effective in combating obesity in humans ( Cheong and Xu, 2021 ). Better understanding the mechanisms by which obesity induces various medical consequences and identification and characterization of novel anti-obesity secreted factors/soluble molecules would be helpful for developing effective therapeutic treatments for obesity and its associated medical complications.

Bluher M. ( 2019 ). Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis . Nat. Rev. Endocrinol . 15 , 288 – 298 .

Google Scholar

Cheong L.Y. , Xu A. ( 2021 ). Intercellular and inter-organ crosstalk in browning of white adipose tissue: molecular mechanism and therapeutic complications . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 13 , 466 – 479 .

Cho N.H. , Shaw J.E. , Karuranga S. , et al. ( 2018 ). IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045 . Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract . 138 , 271 – 281 .

Gao W. , Liu J.-L. , Lu X. , et al. ( 2021 ). Epigenetic regulation of energy metabolism in obesity . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 13 , 480 – 499 .

Huang B. , Xiong X. , Zhang L. , et al. ( 2021 ). PSA controls hepatic lipid metabolism by regulating the NRF2 signaling pathway . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 13 , 527 – 539 .

Loomba R. , Friedman S.L. , Shulman G.I. ( 2021 ). Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease . Cell 184 , 2537 – 2564 .

Love K.M. , Barrett E.J. , Malin S.K. , et al. ( 2021 ). Diabetes pathogenesis and management: the endothelium comes of age . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 13 , 500 – 512 .

Ruan H.-B. ( 2020 ). Developmental and functional heterogeneity of thermogenic adipose tissue . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 12 , 775 – 784 .

Xia X.-D. , Alabi A. , Wang M. , et al. ( 2021 ). Membrane-type I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), lipid metabolism, and therapeutic implications . J. Mol. Cell Biol . 13 , 513 – 526 .

Author notes

Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Clinical Center for Diabetes, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital, Shanghai 200233, China E-mail: [email protected]

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2021 | 130 |

| November 2021 | 124 |

| December 2021 | 74 |

| January 2022 | 81 |

| February 2022 | 149 |

| March 2022 | 125 |

| April 2022 | 146 |

| May 2022 | 128 |

| June 2022 | 123 |

| July 2022 | 115 |

| August 2022 | 101 |

| September 2022 | 123 |

| October 2022 | 183 |

| November 2022 | 199 |

| December 2022 | 151 |

| January 2023 | 191 |

| February 2023 | 298 |

| March 2023 | 466 |

| April 2023 | 545 |

| May 2023 | 632 |

| June 2023 | 831 |

| July 2023 | 388 |

| August 2023 | 559 |

| September 2023 | 495 |

| October 2023 | 515 |

| November 2023 | 477 |

| December 2023 | 394 |

| January 2024 | 444 |

| February 2024 | 504 |

| March 2024 | 525 |

| April 2024 | 661 |

| May 2024 | 664 |

| June 2024 | 464 |

| July 2024 | 329 |

| August 2024 | 448 |

| September 2024 | 182 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1759-4685

- Copyright © 2024 Chinese Academy of Sciences

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- About Project

- Testimonials

Business Management Ideas

Essay on Obesity

List of essays on obesity, essay on obesity – short essay (essay 1 – 150 words), essay on obesity (essay 2 – 250 words), essay on obesity – written in english (essay 3 – 300 words), essay on obesity – for school students (class 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 standard) (essay 4 – 400 words), essay on obesity – for college students (essay 5 – 500 words), essay on obesity – with causes and treatment (essay 6 – 600 words), essay on obesity – for science students (essay 7 – 750 words), essay on obesity – long essay for medical students (essay 8 – 1000 words).

Obesity is a chronic health condition in which the body fat reaches abnormal level. Obesity occurs when we consume much more amount of food than our body really needs on a daily basis. In other words, when the intake of calories is greater than the calories we burn out, it gives rise to obesity.

Audience: The below given essays are exclusively written for school students (Class 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 Standard), college, science and medical students.

Introduction:

Obesity means being excessively fat. A person would be said to be obese if his or her body mass index is beyond 30. Such a person has a body fat rate that is disproportionate to his body mass.

Obesity and the Body Mass Index:

The body mass index is calculated considering the weight and height of a person. Thus, it is a scientific way of determining the appropriate weight of any person. When the body mass index of a person indicates that he or she is obese, it exposes the person to make health risk.

Stopping Obesity:

There are two major ways to get the body mass index of a person to a moderate rate. The first is to maintain a strict diet. The second is to engage in regular physical exercise. These two approaches are aimed at reducing the amount of fat in the body.

Conclusion:

Obesity can lead to sudden death, heart attack, diabetes and may unwanted illnesses. Stop it by making healthy choices.

Obesity has become a big concern for the youth of today’s generation. Obesity is defined as a medical condition in which an individual gains excessive body fat. When the Body Mass Index (BMI) of a person is over 30, he/ she is termed as obese.

Obesity can be a genetic problem or a disorder that is caused due to unhealthy lifestyle habits of a person. Physical inactivity and the environment in which an individual lives, are also the factors that leads to obesity. It is also seen that when some individuals are in stress or depression, they start cultivating unhealthy eating habits which eventually leads to obesity. Medications like steroids is yet another reason for obesity.

Obesity has several serious health issues associated with it. Some of the impacts of obesity are diabetes, increase of cholesterol level, high blood pressure, etc. Social impacts of obesity includes loss of confidence in an individual, lowering of self-esteem, etc.

The risks of obesity needs to be prevented. This can be done by adopting healthy eating habits, doing some physical exercise regularly, avoiding stress, etc. Individuals should work on weight reduction in order to avoid obesity.

Obesity is indeed a health concern and needs to be prioritized. The management of obesity revolves around healthy eating habits and physical activity. Obesity, if not controlled in its initial stage can cause many severe health issues. So it is wiser to exercise daily and maintain a healthy lifestyle rather than being the victim of obesity.

Obesity can be defined as the clinical condition where accumulation of excessive fat takes place in the adipose tissue leading to worsening of health condition. Usually, the fat is deposited around the trunk and also the waist of the body or even around the periphery.

Obesity is actually a disease that has been spreading far and wide. It is preventable and certain measures are to be taken to curb it to a greater extend. Both in the developing and developed countries, obesity has been growing far and wide affecting the young and the old equally.

The alarming increase in obesity has resulted in stimulated death rate and health issues among the people. There are several methods adopted to lose weight and they include different diet types, physical activity and certain changes in the current lifestyle. Many of the companies are into minting money with the concept of inviting people to fight obesity.

In patients associated with increased risk factor related to obesity, there are certain drug therapies and other procedures adopted to lose weight. There are certain cost effective ways introduced by several companies to enable clinic-based weight loss programs.

Obesity can lead to premature death and even cause Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovascular diseases have also become the part and parcel of obese people. It includes stroke, hypertension, gall bladder disease, coronary heart disease and even cancers like breast cancer, prostate cancer, endometrial cancer and colon cancer. Other less severe arising due to obesity includes osteoarthritis, gastro-esophageal reflux disease and even infertility.

Hence, serious measures are to be taken to fight against this dreadful phenomenon that is spreading its wings far and wide. Giving proper education on benefits of staying fit and mindful eating is as important as curbing this issue. Utmost importance must be given to healthy eating habits right from the small age so that they follow the same until the end of their life.

Obesity is majorly a lifestyle disease attributed to the extra accumulation of fat in the body leading to negative health effects on a person. Ironically, although prevalent at a large scale in many countries, including India, it is one of the most neglect health problems. It is more often ignored even if told by the doctor that the person is obese. Only when people start acquiring other health issues such as heart disease, blood pressure or diabetes, they start taking the problem of obesity seriously.

Obesity Statistics in India:

As per a report, India happens to figure as the third country in the world with the most obese people. This should be a troubling fact for India. However, we are yet to see concrete measures being adopted by the people to remain fit.

Causes of Obesity:

Sedentary lifestyle, alcohol, junk food, medications and some diseases such as hypothyroidism are considered as the factors which lead to obesity. Even children seem to be glued to televisions, laptops and video games which have taken away the urge for physical activities from them. Adding to this, the consumption of junk food has further aggravated the growing problem of obesity in children.

In the case of adults, most of the professions of today make use of computers which again makes people sit for long hours in one place. Also, the hectic lifestyle of today makes it difficult for people to spare time for physical activities and people usually remain stressed most of the times. All this has contributed significantly to the rise of obesity in India.

Obesity and BMI:

Body Mass Index (BMI) is the measure which allows a person to calculate how to fit he or she is. In other words, the BMI tells you if you are obese or not. BMI is calculated by dividing the weight of a person in kg with the square of his / her height in metres. The number thus obtained is called the BMI. A BMI of less than 25 is considered optimal. However, if a person has a BMI over 30 he/she is termed as obese.

What is a matter of concern is that with growing urbanisation there has been a rapid increase of obese people in India? It is of utmost importance to consider this health issue a serious threat to the future of our country as a healthy body is important for a healthy soul. We should all be mindful of what we eat and what effect it has on our body. It is our utmost duty to educate not just ourselves but others as well about this serious health hazard.

Obesity can be defined as a condition (medical) that is the accumulation of body fat to an extent that the excess fat begins to have a lot of negative effects on the health of the individual. Obesity is determined by examining the body mass index (BMI) of the person. The BMI is gotten by dividing the weight of the person in kilogram by the height of the person squared.

When the BMI of a person is more than 30, the person is classified as being obese, when the BMI falls between 25 and 30, the person is said to be overweight. In a few countries in East Asia, lower values for the BMI are used. Obesity has been proven to influence the likelihood and risk of many conditions and disease, most especially diabetes of type 2, cardiovascular diseases, sleeplessness that is obstructive, depression, osteoarthritis and some cancer types.

In most cases, obesity is caused through a combination of genetic susceptibility, a lack of or inadequate physical activity, excessive intake of food. Some cases of obesity are primarily caused by mental disorder, medications, endocrine disorders or genes. There is no medical data to support the fact that people suffering from obesity eat very little but gain a lot of weight because of slower metabolism. It has been discovered that an obese person usually expends much more energy than other people as a result of the required energy that is needed to maintain a body mass that is increased.

It is very possible to prevent obesity with a combination of personal choices and social changes. The major treatments are exercising and a change in diet. We can improve the quality of our diet by reducing our consumption of foods that are energy-dense like those that are high in sugars or fat and by trying to increase our dietary fibre intake.

We can also accompany the appropriate diet with the use of medications to help in reducing appetite and decreasing the absorption of fat. If medication, exercise and diet are not yielding any positive results, surgery or gastric balloon can also be carried out to decrease the volume of the stomach and also reduce the intestines’ length which leads to the feel of the person get full early or a reduction in the ability to get and absorb different nutrients from a food.

Obesity is the leading cause of ill-health and death all over the world that is preventable. The rate of obesity in children and adults has drastically increased. In 2015, a whopping 12 percent of adults which is about 600 million and about 100 million children all around the world were found to be obese.

It has also been discovered that women are more obese than men. A lot of government and private institutions and bodies have stated that obesity is top of the list of the most difficult and serious problems of public health that we have in the world today. In the world we live today, there is a lot of stigmatisation of obese people.

We all know how troubling the problem of obesity truly is. It is mainly a form of a medical condition wherein the body tends to accumulate excessive fat which in turn has negative repercussions on the health of an individual.

Given the current lifestyle and dietary style, it has become more common than ever. More and more people are being diagnosed with obesity. Such is its prevalence that it has been termed as an epidemic in the USA. Those who suffer from obesity are at a much higher risk of diabetes, heart diseases and even cancer.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of obesity, it is important to learn what the key causes of obesity are. In a layman term, if your calorie consumption exceeds what you burn because of daily activities and exercises, it is likely to lead to obesity. It is caused over a prolonged period of time when your calorie intake keeps exceeding the calories burned.

Here are some of the key causes which are known to be the driving factors for obesity.

If your diet tends to be rich in fat and contains massive calorie intake, you are all set to suffer from obesity.

Sedentary Lifestyle:

With most people sticking to their desk jobs and living a sedentary lifestyle, the body tends to get obese easily.

Of course, the genetic framework has a lot to do with obesity. If your parents are obese, the chance of you being obese is quite high.

The weight which women gain during their pregnancy can be very hard to shed and this is often one of the top causes of obesity.

Sleep Cycle:

If you are not getting an adequate amount of sleep, it can have an impact on the hormones which might trigger hunger signals. Overall, these linked events tend to make you obese.

Hormonal Disorder:

There are several hormonal changes which are known to be direct causes of obesity. The imbalance of the thyroid stimulating hormone, for instance, is one of the key factors when it comes to obesity.

Now that we know the key causes, let us look at the possible ways by which you can handle it.

Treatment for Obesity:

As strange as it may sound, the treatment for obesity is really simple. All you need to do is follow the right diet and back it with an adequate amount of exercise. If you can succeed in doing so, it will give you the perfect head-start into your journey of getting in shape and bidding goodbye to obesity.

There are a lot of different kinds and styles of diet plans for obesity which are available. You can choose the one which you deem fit. We recommend not opting for crash dieting as it is known to have several repercussions and can make your body terribly weak.

The key here is to stick to a balanced diet which can help you retain the essential nutrients, minerals, and, vitamins and shed the unwanted fat and carbs.

Just like the diet, there are several workout plans for obesity which are available. It is upon you to find out which of the workout plan seems to be apt for you. Choose cardio exercises and dance routines like Zumba to shed the unwanted body weight. Yoga is yet another method to get rid of obesity.

So, follow a blend of these and you will be able to deal with the trouble of obesity in no time. We believe that following these tips will help you get rid of obesity and stay in shape.

Obesity and overweight is a top health concern in the world due to the impact it has on the lives of individuals. Obesity is defined as a condition in which an individual has excessive body fat and is measured using the body mass index (BMI) such that, when an individual’s BMI is above 30, he or she is termed obese. The BMI is calculated using body weight and height and it is different for all individuals.

Obesity has been determined as a risk factor for many diseases. It results from dietary habits, genetics, and lifestyle habits including physical inactivity. Obesity can be prevented so that individuals do not end up having serious complications and health problems. Chronic illnesses like diabetes, heart diseases and relate to obesity in terms of causes and complications.

Factors Influencing Obesity:

Obesity is not only as a result of lifestyle habits as most people put it. There are other important factors that influence obesity. Genetics is one of those factors. A person could be born with genes that predispose them to obesity and they will also have difficulty in losing weight because it is an inborn factor.

The environment also influences obesity because the diet is similar in certain environs. In certain environments, like school, the food available is fast foods and the chances of getting healthy foods is very low, leading to obesity. Also, physical inactivity is an environmental factor for obesity because some places have no fields or tracks where people can jog or maybe the place is very unsafe and people rarely go out to exercise.

Mental health affects the eating habits of individuals. There is a habit of stress eating when a person is depressed and it could result in overweight or obesity if the person remains unhealthy for long period of time.

The overall health of individuals also matter. If a person is unwell and is prescribed with steroids, they may end up being obese. Steroidal medications enable weight gain as a side effect.

Complications of Obesity:

Obesity is a health concern because its complications are severe. Significant social and health problems are experienced by obese people. Socially, they will be bullied and their self-esteem will be low as they will perceive themselves as unworthy.

Chronic illnesses like diabetes results from obesity. Diabetes type 2 has been directly linked to obesity. This condition involves the increased blood sugars in the body and body cells are not responding to insulin as they should. The insulin in the body could also be inadequate due to decreased production. High blood sugar concentrations result in symptoms like frequent hunger, thirst and urination. The symptoms of complicated stages of diabetes type 2 include loss of vision, renal failure and heart failure and eventually death. The importance of having a normal BMI is the ability of the body to control blood sugars.

Another complication is the heightened blood pressures. Obesity has been defined as excessive body fat. The body fat accumulates in blood vessels making them narrow. Narrow blood vessels cause the blood pressures to rise. Increased blood pressure causes the heart to start failing in its physiological functions. Heart failure is the end result in this condition of increased blood pressures.

There is a significant increase in cholesterol in blood of people who are obese. High blood cholesterol levels causes the deposition of fats in various parts of the body and organs. Deposition of fats in the heart and blood vessels result in heart diseases. There are other conditions that result from hypercholesterolemia.

Other chronic illnesses like cancer can also arise from obesity because inflammation of body cells and tissues occurs in order to store fats in obese people. This could result in abnormal growths and alteration of cell morphology. The abnormal growths could be cancerous.

Management of Obesity:

For the people at risk of developing obesity, prevention methods can be implemented. Prevention included a healthy diet and physical activity. The diet and physical activity patterns should be regular and realizable to avoid strains that could result in complications.

Some risk factors for obesity are non-modifiable for example genetics. When a person in genetically predisposed, the lifestyle modifications may be have help.

For the individuals who are already obese, they can work on weight reduction through healthy diets and physical exercises.

In conclusion, obesity is indeed a major health concern because the health complications are very serious. Factors influencing obesity are both modifiable and non-modifiable. The management of obesity revolves around diet and physical activity and so it is important to remain fit.

In olden days, obesity used to affect only adults. However, in the present time, obesity has become a worldwide problem that hits the kids as well. Let’s find out the most prevalent causes of obesity.

Factors Causing Obesity:

Obesity can be due to genetic factors. If a person’s family has a history of obesity, chances are high that he/ she would also be affected by obesity, sooner or later in life.

The second reason is having a poor lifestyle. Now, there are a variety of factors that fall under the category of poor lifestyle. An excessive diet, i.e., eating more than you need is a definite way to attain the stage of obesity. Needless to say, the extra calories are changed into fat and cause obesity.

Junk foods, fried foods, refined foods with high fats and sugar are also responsible for causing obesity in both adults and kids. Lack of physical activity prevents the burning of extra calories, again, leading us all to the path of obesity.

But sometimes, there may also be some indirect causes of obesity. The secondary reasons could be related to our mental and psychological health. Depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional troubles are well-known factors of obesity.

Physical ailments such as hypothyroidism, ovarian cysts, and diabetes often complicate the physical condition and play a massive role in abnormal weight gain.

Moreover, certain medications, such as steroids, antidepressants, and contraceptive pills, have been seen interfering with the metabolic activities of the body. As a result, the long-term use of such drugs can cause obesity. Adding to that, regular consumption of alcohol and smoking are also connected to the condition of obesity.

Harmful Effects of Obesity:

On the surface, obesity may look like a single problem. But, in reality, it is the mother of several major health issues. Obesity simply means excessive fat depositing into our body including the arteries. The drastic consequence of such high cholesterol levels shows up in the form of heart attacks and other life-threatening cardiac troubles.

The fat deposition also hampers the elasticity of the arteries. That means obesity can cause havoc in our body by altering the blood pressure to an abnormal range. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Obesity is known to create an endless list of problems.

In extreme cases, this disorder gives birth to acute diseases like diabetes and cancer. The weight gain due to obesity puts a lot of pressure on the bones of the body, especially of the legs. This, in turn, makes our bones weak and disturbs their smooth movement. A person suffering from obesity also has higher chances of developing infertility issues and sleep troubles.

Many obese people are seen to be struggling with breathing problems too. In the chronic form, the condition can grow into asthma. The psychological effects of obesity are another serious topic. You can say that obesity and depression form a loop. The more a person is obese, the worse is his/ her depression stage.

How to Control and Treat Obesity:

The simplest and most effective way, to begin with, is changing our diet. There are two factors to consider in the diet plan. First is what and what not to eat. Second is how much to eat.

If you really want to get rid of obesity, include more and more green vegetables in your diet. Spinach, beans, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, asparagus, etc., have enough vitamins and minerals and quite low calories. Other healthier options are mushrooms, pumpkin, beetroots, and sweet potatoes, etc.

Opt for fresh fruits, especially citrus fruits, and berries. Oranges, grapes, pomegranate, pineapple, cherries, strawberries, lime, and cranberries are good for the body. They have low sugar content and are also helpful in strengthening our immune system. Eating the whole fruits is a more preferable way in comparison to gulping the fruit juices. Fruits, when eaten whole, have more fibers and less sugar.

Consuming a big bowl of salad is also great for dealing with the obesity problem. A salad that includes fibrous foods such as carrots, radish, lettuce, tomatoes, works better at satiating the hunger pangs without the risk of weight gain.

A high protein diet of eggs, fish, lean meats, etc., is an excellent choice to get rid of obesity. Take enough of omega fatty acids. Remember to drink plenty of water. Keeping yourself hydrated is a smart way to avoid overeating. Water also helps in removing the toxins and excess fat from the body.

As much as possible, avoid fats, sugars, refined flours, and oily foods to keep the weight in control. Control your portion size. Replace the three heavy meals with small and frequent meals during the day. Snacking on sugarless smoothies, dry fruits, etc., is much recommended.

Regular exercise plays an indispensable role in tackling the obesity problem. Whenever possible, walk to the market, take stairs instead of a lift. Physical activity can be in any other form. It could be a favorite hobby like swimming, cycling, lawn tennis, or light jogging.

Meditation and yoga are quite powerful practices to drive away the stress, depression and thus, obesity. But in more serious cases, meeting a physician is the most appropriate strategy. Sometimes, the right medicines and surgical procedures are necessary to control the health condition.

Obesity is spreading like an epidemic, haunting both the adults and the kids. Although genetic factors and other physical ailments play a role, the problem is mostly caused by a reckless lifestyle.

By changing our way of living, we can surely take control of our health. In other words, it would be possible to eliminate the condition of obesity from our lives completely by leading a healthy lifestyle.

Health , Obesity

Get FREE Work-at-Home Job Leads Delivered Weekly!

Join more than 50,000 subscribers receiving regular updates! Plus, get a FREE copy of How to Make Money Blogging!

Message from Sophia!

Like this post? Don’t forget to share it!

Here are a few recommended articles for you to read next:

- Essay on Cleanliness

- Essay on Cancer

- Essay on AIDS

- Essay on Health and Fitness

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Billionaires

- Donald Trump

- Warren Buffett

- Email Address

- Free Stock Photos

- Keyword Research Tools

- URL Shortener Tools

- WordPress Theme

Book Summaries

- How To Win Friends

- Rich Dad Poor Dad

- The Code of the Extraordinary Mind

- The Luck Factor

- The Millionaire Fastlane

- The ONE Thing

- Think and Grow Rich

- 100 Million Dollar Business

- Business Ideas

Digital Marketing

- Mobile Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

- Computer Addiction

- Drug Addiction

- Internet Addiction

- TV Addiction

- Healthy Habits

- Morning Rituals

- Wake up Early

- Cholesterol

- Reducing Cholesterol

- Fat Loss Diet Plan

- Reducing Hair Fall

- Sleep Apnea

- Weight Loss

Internet Marketing

- Email Marketing

Law of Attraction

- Subconscious Mind

- Vision Board

- Visualization

Law of Vibration

- Professional Life

Motivational Speakers

- Bob Proctor

- Robert Kiyosaki

- Vivek Bindra

- Inner Peace

Productivity

- Not To-do List

- Project Management Software

- Negative Energies

Relationship

- Getting Back Your Ex

Self-help 21 and 14 Days Course

Self-improvement.

- Body Language

- Complainers

- Emotional Intelligence

- Personality

Social Media

- Project Management

- Anik Singal

- Baba Ramdev

- Dwayne Johnson

- Jackie Chan

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Narendra Modi

- Nikola Tesla

- Sachin Tendulkar

- Sandeep Maheshwari

- Shaqir Hussyin

Website Development

Wisdom post, worlds most.

- Expensive Cars

Our Portals: Gulf Canada USA Italy Gulf UK

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention: A Framework to Inform Decision Making (2010)

Chapter: 10 conclusions and recommendations, 10 conclusions and recommendations.

D ecisions about prevention are complex, not only for the obesity problem but also for other problems with multiple types and layers of causation. Recognition of the need to emphasize population-based approaches to obesity prevention, the urgency of taking action, and the desire of many decision makers to have evidence on which actions to take have created a demand for evidence with which to answer a range of questions. In reality, the evidence approaches that apply to decision making about the treatment of obesity or other clinical problems are inadequate and sometimes inappropriate for application to decisions about public health initiatives. The need to work around evidence gaps and the limitations of using evidence hierarchies that apply to medical treatment for assessing population-based preventive interventions have been faced by the developers of several prior Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports on obesity prevention (focused on child and adolescent obesity). These evidence issues are not new and have already been the focus of many efforts in the field of public health in relation to other complex health problems. However, they are far from resolved. Considering these issues in relation to obesity prevention has the potential to advance the field of public health generally while also meeting the immediate need for clarity on evidence issues related to addressing the obesity epidemic.

The IOM’s Food and Nutrition Board formed the Committee on an Evidence Framework for Obesity Prevention Decision Making, with funding from Kaiser Permanente, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This committee was asked to develop a framework for evidence-informed decision making in obesity prevention, focused on approaches for assessing policy, environmental, and community interventions designed to influence diet and physical activity. The committee was tasked to:

provide an overview of the nature of the evidence base for obesity prevention as it is currently construed;

identify the challenges associated with integrating scientific evidence with broader influences on policy and programmatic considerations;

provide a practical and action-oriented framework of recommendations for how to select, implement, and evaluate obesity prevention efforts;

identify ways in which existing or new tools and methods can be used to build a useful and timely evidence base appropriate to the challenges presented by the epidemic, and describe ongoing attempts to meet these challenges;

develop a plan for communicating and disseminating the proposed framework and its recommendations; and

specify a plan for evaluating and refining the proposed framework in current decision-making processes.

CONCLUSIONS

Recognition is increasing that overweight and obesity are not only problems of individuals, but also societywide problems of populations. Acting on this recognition will require multifaceted, population-based changes in the socioenvironmental variables that influence energy intake and expenditure. There exist both a pressing need to act on the problem of obesity and a large gap between the type and amount of evidence needed to act and the type and amount of evidence available to meet that need. A new framework is necessary to assist researchers and a broad community of decision makers in generating, identifying, and evaluating the best evidence available and in summarizing it for use in decision making. This new framework also is important for researchers attempting to fill important evidence gaps through studies based on questions with program and policy relevance. However, the methods used and the evidence generated by traditional research designs do not yield all the types of evidence useful to inform actions aimed at addressing obesity prevention and other complex public health challenges. An expanded approach is needed that emphasizes the decision-making process and contextual considerations.

The Framework

To meet this need, the committee developed the L.E.A.D. ( L ocate Evidence, E valuate Evidence, A ssemble Evidence, and Inform D ecisions) framework, designed to facilitate a systematic approach to the identification, implementation, and evaluation of promising, reasonable actions to address obesity prevention and other complex public health challenges (see Figure 10-1 ). The framework is designed to help identify the nature of the evidence that is needed and clarify what changes in current approaches to generating and evaluating evidence will facilitate meeting those needs. This section describes the main components of the framework and issues related to these components.

Obesity prevention has not been addressed successfully by traditional study designs, which are generally linear and static. A systems approach is needed to develop more complex, interdisciplinary strategies. Accordingly, the L.E.A.D. framework

FIGURE 10-1 The L ocate Evidence, E valuate Evidence, A ssemble Evidence, Inform D ecisions (L.E.A.D.) framework for obesity prevention decision making.

recommends taking a systems perspective. In other words, it is necessary to use an approach that encompasses the whole picture, highlighting the broader context and interactions among levels, to capture the complexity of obesity prevention and other multifactorial public health challenges.

Addressing such challenges first requires specifying the question(s) being asked to guide the identification of evidence that is appropriate, inclusive, and relevant. Core to the framework is the orientation of the user. A variety of decisions have to be made to address obesity prevention. To capture the resulting mix of evidence needs, the framework adopts a typology that differentiates three broad categories of interrelated questions of potential interest to the user: Why should we do something about this problem? What specifically should we do? and How do we implement this information for our situation? This “Why,” “What,” “How” typology stresses the need for multiple types of evidence to support decisions on obesity prevention.

Once the question(s) of interest have been specified, locating useful evidence requires clear knowledge of the types of information that may be useful and an awareness of where that information can be found. The framework calls for the use of

diverse approaches to gather and synthesize information from other disciplines that address issues similar to those faced in obesity prevention and public health generally. Evidence identified and gathered to inform decision making for obesity prevention and other complex public health challenges should be assessed based on both its generalizability and level of certainty (i.e., its external and internal validity, respectively). The L.E.A.D. framework addresses these two key aspects of the evidence through the nature of the question(s) being asked, established criteria for the value of evidence, and the context in which the question(s) arise. Results of the overall evaluation of evidence should provide answers on what to do, how to do it, and how strongly the action is justified.

When decision makers are coming to a decision on obesity prevention actions, it is important for them to understand the state of the available knowledge relevant to that decision. This knowledge includes evidence on the specific problem to be addressed, the likely effectiveness and impact of proposed actions, and key considerations involved in their implementation. Successful evidence gathering, evaluation, and synthesis for use in obesity prevention usually require the involvement of a number of disciplines using a variety of methodologies and technical languages. The framework incorporates a standardized approach using a uniform language and structure for summarizing the relevant evidence in a systematic, transparent, and transdisciplinary way that is critical for communicating the process and conclusions clearly.

With an emergent problem such as obesity, decisions to act often must be made in the face of a relative absence of evidence, or evidence that is inconclusive, inconsistent, or incomplete. Evidence gathered from a particular intervention implemented in a closely controlled manner within a specific population with its own unique characteristics is often difficult to apply to a similar intervention with another population. The typical way of presenting results of obesity prevention efforts in journals often adds to the problem of incomplete evidence because useful aspects of the research related to its generalizability are not reported. If obesity prevention actions must be taken when evidence is limited, this incomplete evidence can be blended with theory, expert opinion, experience, and local wisdom to make the best decision possible. The actions taken then should undergo critical evaluation, the results of which should be used to build credible evidence for use in decision making about future efforts. Important alternatives to waiting for the funding, implementation, and publication of formal research on obesity prevention are natural experiments as sources of practice-based evidence, “evaluability assessment” of emerging innovations (defined as assessing whether a program is ready for full-scale evaluation), and continuous quality assessment of ongoing programs. The L.E.A.D. framework process leads to knowledge integration, or the incorporation of new knowledge gained through the process of applying the framework into the context of the organization or system where decisions are made.

The evidence base to support the identification of effective obesity prevention interventions is limited in many areas. Opportunities to generate evidence may occur

at any phase of the evidence review or decision-making process. The L.E.A.D. framework guides the generation of evidence related to “What,” “Why,” and “How” questions and supports the use of multiple forms of evidence and research designs from a variety of disciplines. In obesity prevention–related research, the generation of evi dence from evaluation of ongoing and emerging initiatives is a particular priority.

Researchers, decision makers, and intermediaries working on obesity prevention and other complex multifactorial public health problems are the primary audiences for communicating and disseminating the L.E.A.D. framework. With sufficient information, they can apply the framework as a guide for generating needed evidence and supporting decision making. It is important to understand the settings, communication channels, and activities of these key audiences to engage and educate them effectively on the purpose and adoption of the framework. To support the development of a communication and dissemination plan, it is critical to create partnerships, make use of existing activities and networks, and tailor the messages and approaches to each target audience.

As the target audiences begin to use the framework, assessing its use in selected settings will be essential so it can be improved and refined. Evaluation of the impact of the L.E.A.D. framework is also important for determining its relevance to current evidence-generation and decision-making processes. To this end, key outcome measures—utilization, adoption, acceptance, maintenance, and impact—should be defined and data collected on these measures. It will be important to develop or adopt data collection tools and utilize methods and existing initiatives that will best serve this purpose, as well as to systematically integrate the feedback thus obtained to sustain and improve the framework’s applicability and utilization.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States has made progress toward translating science into practice in the brief time since the obesity epidemic was officially recognized. But the pace of this translation has been slow relative to the scope and urgency of the problem and the associated harms and costs. As discussed above, moreover, the evidence emerging from applied research on obesity prevention can be inconclusive, incomplete, and inconsistent. A systematic process is needed to improve the use of available evidence and increase and enhance the evidence base to inform decisions on obesity prevention and other complex public health problems. Commitment to such a process is needed from both decision makers and those involved in generating evidence, including public and private policy makers and their advisors, scientific and policy think tanks, advocacy groups and stakeholders, program planners, practitioners in public health and other sectors, program evaluators, public health researchers and research scientists, journal editors, and funders. With this in mind, the committee makes the following recom-

mendations for assisting decision makers and researchers in using the current evidence base for obesity prevention and for taking a systems-oriented, transdisciplinary approach to generate more, and more useful, evidence.

Utilize the L.E.A.D. Framework

Recommendation 1: Decision makers and those involved in generating evidence, including researchers, research funders, and publishers of research, should apply the L.E.A.D. framework as a guide in their utilization and generation of evidence to support decision making for complex, multifactorial public health challenges, including obesity prevention.

Key assumptions that should guide the use of the framework include the following:

A systems perspective can help in framing and explaining complex issues.

The types of evidence that should be gathered to inform decision making are based on the nature of the questions being asked, including Why? (“Why should we do something about this problem in our situation?”), What? (“What specifically should we do about this problem?”), and How? (“How do we implement this information for our situation?”). A focus on subsets of these questions as a starting point in gathering evidence explicitly expands the evidence base that is typically identified and gathered.

The quality of the evidence should be judged according to established criteria for that type of evidence.

Both the level of certainty of the causal relationship between an intervention and the observed outcomes and the intervention’s generalizability to other individuals, settings, contexts, and time frames should be given explicit attention.

The analysis of the evidence to be used in making a decision should be summarized and communicated in a systematic, transparent, and transdisciplinary manner that uses uniform language and structure. The report on this analysis should include a summary of the question(s) asked by the decision maker; the strategy for gathering and selecting the evidence; an evidence table showing the sources, types, and quality of the evidence and the outcomes reported; and a concise summary of the synthesis of selected evidence on why an action should be taken, what that action should be, and how it should be taken.

If action must be taken when evidence is limited, this incomplete evidence can be blended carefully and transparently with theory, expert opinion, and collaboration based on professional experience and local wisdom to support making the best decision.

Sustained commitments will be needed from both the public and private sectors to achieve successful utilization of the various elements of the L.E.A.D. framework in future evidence-informed decision making and evidence generation. This respon-

sibility lies with the academic and research community, as well as with government and private funders and the leadership of journals that publish research in this area. Necessary supports will include increasing understanding of systems thinking and incorporating it into research-related activities, creating and maintaining resources to support the utilization of evidence, establishing standards of quality for different types of evidence, and supporting the generation of evidence, each of which is described in more detail below. Finally, it will be necessary to communicate, disseminate, evaluate, and refine the L.E.A.D. framework.

Incorporate Systems Thinking

Recommendation 2: Researchers, government and private funders, educators, and journal editors should incorporate systems thinking into their research-related activities.

To implement this recommendation:

Researchers should use systems thinking to guide the development of environmental and policy interventions and study designs.

Government and private funders should encourage the use of systems thinking in their requests for proposals and include systems considerations in proposal evaluations.

Universities, government agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and public health organizations responsible for educating public health practitioners and related researchers should establish training capacity for the science and understanding of systems thinking and the use of systems mapping and other quantitative or qualitative systems analysis tools.

Journal editors should encourage the use of systems thinking for addressing complex problems by developing panels of peer reviewers with expertise in this area and charging them with making recommendations for how authors could use systems thinking more effectively in their manuscripts.

Build a Resource Base

Recommendation 3: Government, foundations, professional organizations, and research institutions should build a system of resources (people, compendiums of knowledge, registries of implementation experience) to support evidence-based public policy decision making and research for complex health challenges, including obesity prevention.

The Secretary of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with other public- and private-sector partners, should establish a sustainable registry of reports on evidence for environmental and policy actions for obesity prevention.

Integral to this registry should be the expanded view of evidence for decision making on obesity prevention proposed in this report and the sharing of experiences and innovative programs as the evidence evolves. A service provided by this registry should be periodic synthesis reviews based on mixed qualitative and quantitative methods.

The Secretary of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with other public- and private-sector partners, should develop and fund a resource for compiling and linking existing databases that may contain useful evidence for obesity prevention and related public health initiatives. This resource should include links to data and research from disciplines and sectors outside of obesity prevention and public health and to data from nonacademic sources that are of interest to decision makers.

Establish Standards for Evidence Quality

Recommendation 4: Government, foundations, professional organizations, and research institutions should catalyze and support the establishment of guidance on standards for evaluating the quality of evidence for which such standards are lacking.

Government and private funders should give priority to funding for the development of guidance on standards for evaluating the quality of the full range of evidence types discussed in this report that are useful in making obesity prevention decisions, especially those for which the scientific literature is limited.

Professional organizations and research institutions should encourage and bring attention to efforts by faculty, researchers, and students to establish guidance in this area.

Support the Generation of Evidence

Recommendation 5: Obesity prevention research funders, researchers, and publishers should consider, wherever appropriate, the inclusion in research studies of a focus on the generalizability of the find ings and related implementation issues at every stage, from conception through publication.

Those funding research in obesity prevention should give priority to support for studies that include an assessment of the limitations, potential utility, and applicability of the research beyond the particular population, setting, and circumstances in which the studies are conducted, including by initiating requests for applications and similar calls for proposals aimed at such studies. Additional ways in which this recommendation could be implemented include adding crite-

ria related to generalizability to proposal review procedures and training reviewers to evaluate generalizability.

Obesity prevention researchers and program evaluators should give special consideration to study designs that maximize evidence on generalizability.

Journal editors should provide guidelines and space for authors to give richer descriptions of interventions and the conditions under which they are tested to clarify their generalizability.

Recommendation 6: Research funders should increase opportunities for those carrying out obesity pre vention initiatives to measure and share their outcomes so others can learn from their experience.

Organizations funding or sponsoring obesity prevention initiatives—including national, regional, statewide, or local programs; policy changes; and environmental initiatives—should provide resources for obtaining practice-based evidence from innovative and ongoing programs and policies in a more routine, timely, and systematic manner to capture their processes, implementation, and outcomes. These funders should also encourage and support assessments of the potential for evaluating the most innovative programs in their jurisdictions and sponsor scientific evaluations where the opportunities to advance generalizable evidence are greatest.

Research funders, researchers, and journal editors should assign higher priority to studies that test obesity prevention interventions in real-world settings in which major contextual variables are identified and their influence is evaluated.

Recommendation 7: Research funders should encourage collaboration among researchers in a variety of disciplines so as to utilize a full range of research designs that may be feasible and appropriate for evaluating obesity prevention and related public health initiatives.

As part of their requests for proposals on obesity prevention research, funders should give priority to and reward transdisciplinary collaborations that include the creative use of research designs that have not been extensively used in prevention research but hold promise for expanding the evidence base on potential environmental and policy solutions.

Communicate, Disseminate, Evaluate, and Refine the L.E.A.D. Framework

Recommendation 8: A public–private consortium should bring together researchers, research funders, publishers of research, decision makers, and other stakeholders to discuss the practical uses of the

L.E.A.D. framework, and develop plans and a timeline for focused experimentation with the frame work and for its evaluation and potential refinement.

Interested funders should bring together a consortium of representatives of key stakeholders (including decision makers, government funders, private funders, academic institutions, professional organizations, researchers, and journal editors) who are committed to optimizing the use of the current obesity prevention evidence base and developing a broader and deeper base of evidence.

This consortium should develop an action-oriented plan for funding and implementing broad communication, focused experimentation, evaluation, and refinement of the L.E.A.D. framework. This plan should be based on the major purposes of the framework: to significantly improve the evidence base for obesity prevention decision making on policy and environmental solutions, and to assist decision makers in using the evidence base.

To battle the obesity epidemic in America, health care professionals and policymakers need relevant, useful data on the effectiveness of obesity prevention policies and programs. Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention identifies a new approach to decision making and research on obesity prevention to use a systems perspective to gain a broader understanding of the context of obesity and the many factors that influence it.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 23 September 2021

The genetics of obesity: from discovery to biology

- Ruth J. F. Loos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8532-5087 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 &

- Giles S. H. Yeo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8823-3615 5

Nature Reviews Genetics volume 23 , pages 120–133 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

158k Accesses

466 Citations

484 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Disease genetics

- Endocrine system and metabolic diseases

- Genetic association study

- Genetic variation

The prevalence of obesity has tripled over the past four decades, imposing an enormous burden on people’s health. Polygenic (or common) obesity and rare, severe, early-onset monogenic obesity are often polarized as distinct diseases. However, gene discovery studies for both forms of obesity show that they have shared genetic and biological underpinnings, pointing to a key role for the brain in the control of body weight. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with increasing sample sizes and advances in sequencing technology are the main drivers behind a recent flurry of new discoveries. However, it is the post-GWAS, cross-disciplinary collaborations, which combine new omics technologies and analytical approaches, that have started to facilitate translation of genetic loci into meaningful biology and new avenues for treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

A phenome-wide comparative analysis of genetic discordance between obesity and type 2 diabetes

Obesity: exploring its connection to brain function through genetic and genomic perspectives

Genome-wide discovery of genetic loci that uncouple excess adiposity from its comorbidities

Introduction.

Obesity is associated with premature mortality and is a serious public health threat that accounts for a large proportion of the worldwide non-communicable disease burden, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and certain cancers 1 , 2 . Mechanical issues resulting from substantially increased weight, such as osteoarthritis and sleep apnoea, also affect people’s quality of life 3 . The impact of obesity on communicable disease, in particular viral infection 4 , has recently been highlighted by the discovery that individuals with obesity are at increased risk of hospitalization and severe illness from COVID-19 (refs 5 , 6 , 7 ).

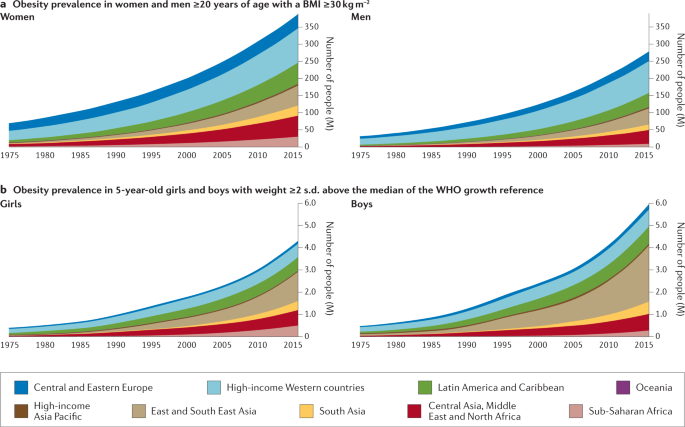

On the basis of the latest data from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, in 2016 almost 2 billion adults (39% of the world’s adult population) were estimated to be overweight (defined by a body mass index (BMI) of ≥25 kg m − 2 ), 671 million (12% of the world’s adult population) of whom had obesity (BMI ≥30 kg m − 2 ) — a tripling in the prevalence of obesity since 1975 (ref. 8 ) (Fig. 1 ). Although the rate of increase in obesity seems to be declining in most high-income countries, it continues to rise in many low-income and middle-income countries and prevalence remains high globally 8 . If current trends continue, it is expected that 1 billion adults (nearly 20% of the world population) will have obesity by 2025. Particularly alarming is the global rise in obesity among children and adolescents; more than 7% had obesity in 2016 compared with less than 1% in 1975 (ref. 8 ).

The prevalence of obesity has risen steadily over the past four decades in children, adolescents (not shown) and adults worldwide. a | Prevalence of obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg m −2 ) in women and men ≥20 years of age, from 1975 to 2016. b | Prevalence of obesity (weight ≥2 s.d. above the median of the WHO growth reference) in 5-year-old girls and boys from 1975 to 2016. Geographical regions are represented by different colours. Graphs are reproduced from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD RisC) website and are generated from data published in ref. 8 .

Although changes in the environment have undoubtedly driven the rapid increase in prevalence, obesity results from an interaction between environmental and innate biological factors. Crucially, there is a strong genetic component underlying the large interindividual variation in body weight that determines people’s response to this ‘obesogenic’ environment . Twin, family and adoption studies have estimated the heritability of obesity to be between 40% and 70% 9 , 10 . As a consequence, genetic approaches can be leveraged to characterize the underlying physiological and molecular mechanisms that control body weight.

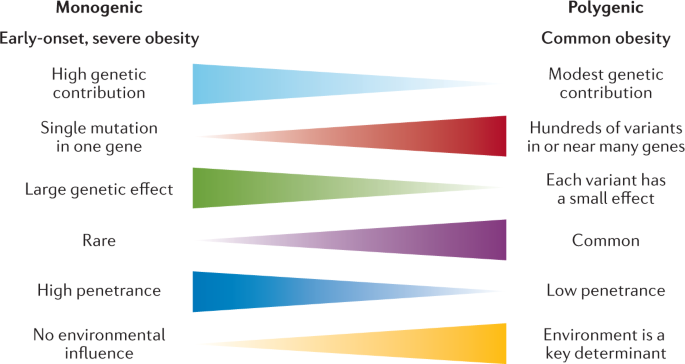

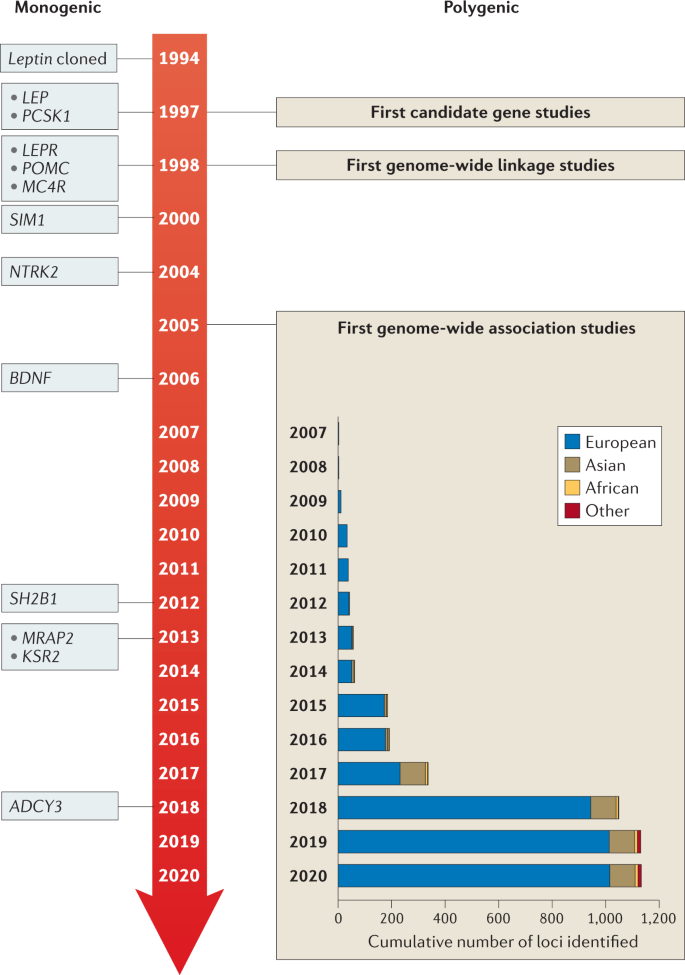

Classically, we have considered obesity in two broad categories (Fig. 2 ): so-called monogenic obesity , which is inherited in a Mendelian pattern, is typically rare, early-onset and severe and involves either small or large chromosomal deletions or single-gene defects; and polygenic obesity (also known as common obesity), which is the result of hundreds of polymorphisms that each have a small effect. Polygenic obesity follows a pattern of heritability that is similar to other complex traits and diseases. Although often considered to be two distinct forms, gene discovery studies of monogenic and polygenic obesity have converged on what seems to be broadly similar underlying biology. Specifically, the central nervous system (CNS) and neuronal pathways that control the hedonic aspects of food intake have emerged as the major drivers of body weight for both monogenic and polygenic obesity. Furthermore, early evidence shows that the expression of mutations causing monogenic obesity may — at least in part — be influenced by the individual’s polygenic susceptibility to obesity 11 .

Key features of monogenic and polygenic forms of obesity .

In this Review, we summarize more than 20 years of genetic studies that have characterized the molecules and mechanisms that control body weight, specifically focusing on overall obesity and adiposity, rather than fat distribution or central adiposity. Although most of the current insights into the underlying biology have been derived from monogenic forms of obesity, recent years have witnessed several successful variant-to-function translations for polygenic forms of obesity. We also explore how the ubiquity of whole-exome sequencing (WES) and genome sequencing has begun to blur the line that used to demarcate the monogenic causes of obesity from common polygenic obesity. Syndromic forms of obesity, such as Bardet–Biedl, Prader–Willi, among many others 12 , are not reviewed here. Although obesity is often a dominant feature of these syndromes, the underlying genetic defects are often chromosomal abnormalities and typically encompass multiple genes, making it difficult to decipher the precise mechanisms directly related to body-weight regulation. Finally, as we enter the post-genomic era, we consider the prospects of genotype-informed treatments and the possibility of leveraging genetics to predict and hence prevent obesity.

Gene discovery approaches

The approaches used to identify genes linked to obesity depend on the form of obesity and genotyping technology available at the time. Early gene discovery studies for monogenic forms of obesity had a case-focused design: patients with severe obesity, together with their affected and unaffected family members, were examined for potential gene-disrupting causal mutations via Sanger sequencing. By contrast, genetic variation associated with common forms of obesity have been identified in large-scale population studies, either using a case–control design or continuous traits such as BMI. Gene discovery for both forms of obesity was initially hypothesis driven; that is, restricted to a set of candidate genes that evidence suggests have a role in body-weight regulation. Over the past two decades, however, advances in high-throughput genome-wide genotyping and sequencing technologies, combined with a detailed knowledge of the human genetic architecture, have enabled the interrogation of genetic variants across the whole genome for their role in body-weight regulation using a hypothesis-generating approach.

Gene discovery for monogenic obesity

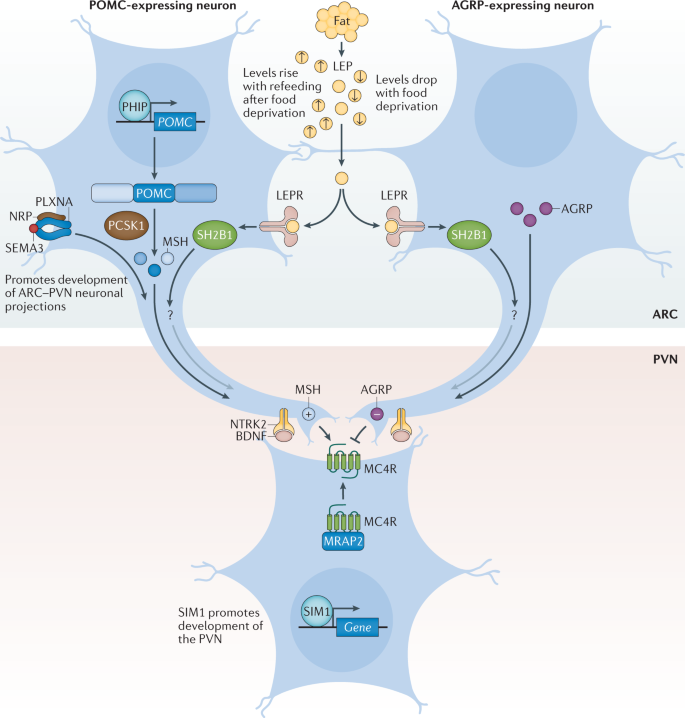

Many of the candidate genes and pathways linked to body-weight regulation were initially identified in mice, such as the obese ( ob ) 13 and diabetes ( db ) 14 mouse lines, in which severe hyperphagia and obesity spontaneously emerged. Using reverse genetics , the ob gene was shown to encode leptin, a hormone produced from fat, and it was demonstrated that leptin deficiency resulting from a mutation in the ob gene caused the severe obesity seen in the ob/ob mouse 15 (Fig. 3 ). Shortly after the cloning of ob , the db gene was cloned and identified as encoding the leptin receptor (LEPR) 16 . Reverse genetics was also used to reveal that the complex obesity phenotype of Agouti ‘lethal yellow’ mice is caused by a rearrangement in the promoter sequence of the agouti gene that results in ectopic and constitutive expression of the agouti peptide 17 , 18 , which antagonizes the melanocortin 1 and 4 receptors (MC1R and MC4R) 19 , 20 . This finding linked the melanocortin pathway to body-weight regulation, thereby unveiling a whole raft of new candidate genes for obesity.