- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Creating Lesson Plans

How to Write an Educational Objective

Last Updated: December 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 351,871 times.

An educational objective is an important tool for teaching. It allows you to articulate your expectations for your students, which can inform you as you write lesson plans, test, quizzes, and assignment sheets. There is a specific formula that goes into writing educational objectives. Learning to master that formula can help you write excellent educational objectives for you and your students.

Planning Your Objective

- Goals are broad and often difficult to measure in an objective sense. They tend to focus on big picture issues. For example, in a college class on child psychology, a goal might be "Students will learn to appreciate the need for clinical training when dealing with small children." While such a goal would obviously inform the more specific educational objectives, it is not specific enough to be an objective itself.

- Educational objectives are much more specific. They include measurable verbs and criteria for acceptable performance or proficiency regarding a particular subject. For example, "By the end of this unit, students will be able to identify three theorists whose work on child psychology influenced teaching practices in the US." This is a more specific educational objective, based on the educational for the same hypothetical course.

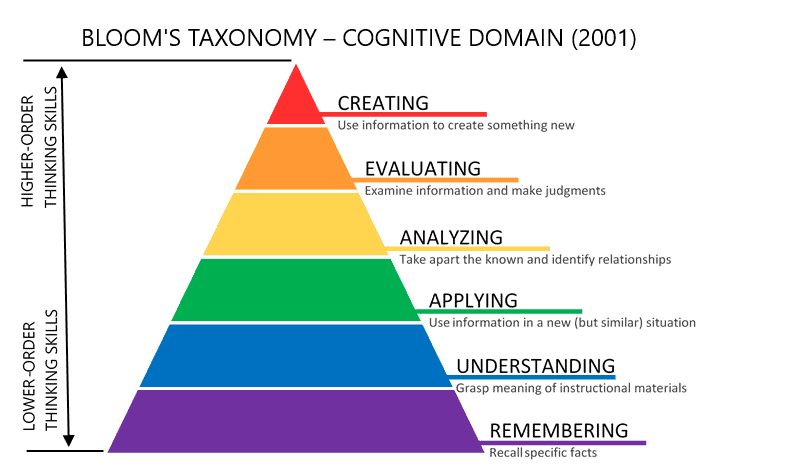

- Bloom identified three domains of learning. The cognitive domain is the domain given the most focus in the world of higher education. Cognitive is the domain used for guidance when writing educational objectives. The cognitive domain focuses on intellectual, scholarly learning and is divided into a hierarchy consisting of six levels.

- Example: Memorizing multiplication tables.

- Example: Recalling when the Battle of Hastings occurred.

- Example: Translating a Japanese sentence into German.

- Example: Explaining why nuclear technology affected President Reagan's political policies.

- Example: Using pi to solve various mathematical problems.

- Example: Using "please" to ask for things politely not just with Mom, but other people.

- Example: Understanding the concept of "fate" as a predetermined destiny.

- Example: A ball thrown on the ground falls, a rock thrown on the ground falls...but what happens if they are thrown into water?

- Example: Creating a painting.

- Example: Putting forth a new idea about subatomic particles.

- Example: Creating a short film humanizing immigrants in your community with commentary on why you believe they deserve respect.

- Example: Writing an essay on why you believe Hamlet really did not love Ophelia.

- Performance is the first characteristic. An object should always state what your students are expected to be able to do by the end of a unit or class.

- Condition is the second characteristic. A good educational objective will outline the conditions under which a student is supposed to perform said task.

- Criterion, the third characteristic, outlines how well a student must perform. That is, the specific expectations that need to be met for their performance to be passing.

- For example, say you are teaching a nursing class. A good educational objective would be "By the end of this course, students will be able to draw blood, in typical hospital settings, within a 2 to 3 minute timeframe." This outlines the performance, drawing blood, the conditions, typical hospital settings, and the criterion, the task being performed in 2 to 3 minutes.

Writing Your Educational Objective

- Example: After completing this lesson, students are expected to be able to write a paragraph using a topic sentence.

- Example: After completing this lesson, students are expected to be able to identify three farm animals.

- Example: By midterm, all students should be able to count to 20.

- Example: At the end of the workshop, students should produce a haiku.

- For knowledge, go for words like list, recite, define, and name.

- For comprehension, words like describe, explain, paraphrase, and restate are ideal.

- Application objectives should include verbs like calculate, predict, illustrate, and apply.

- For analysis, go for terms like categorize, analyze, diagram, and illustrate.

- For synthesis, use words like design, formulate, build, invent, and create.

- For evaluation, try terms like choose, relate, contrast, argue, and support.

- What performance do you expect? Do students simply need to list or name something? Should they understand how to perform a task?

- Where and when will they carry out this performance? Is this for a classroom setting alone or do they need to perform in a clinical, real world environment?

- What are the criteria you're using to evaluate your student? What would be considered a passing grade or an appropriate performance?

- Say you're teaching a high school English class and, for one lesson, you're teaching symbolism. A good educational objective would be, "By the end of this lesson, students should be able to analyze the symbolism in a given passage of literature and interpret the work's meaning in their own words."

- The stem statement identifies that the objective should be met by the end of the lesson.

- The verbs used are comprehension verbs, indicating this task falls under the second level of Bloom's hierarchy of learning.

- The expected performance is literary analysis. The condition is, presumably, that the reading be done alone. The expected outcome is that the student will be able to read a work, analyze it, and explain it in her own words.

Reviewing Your Objectives

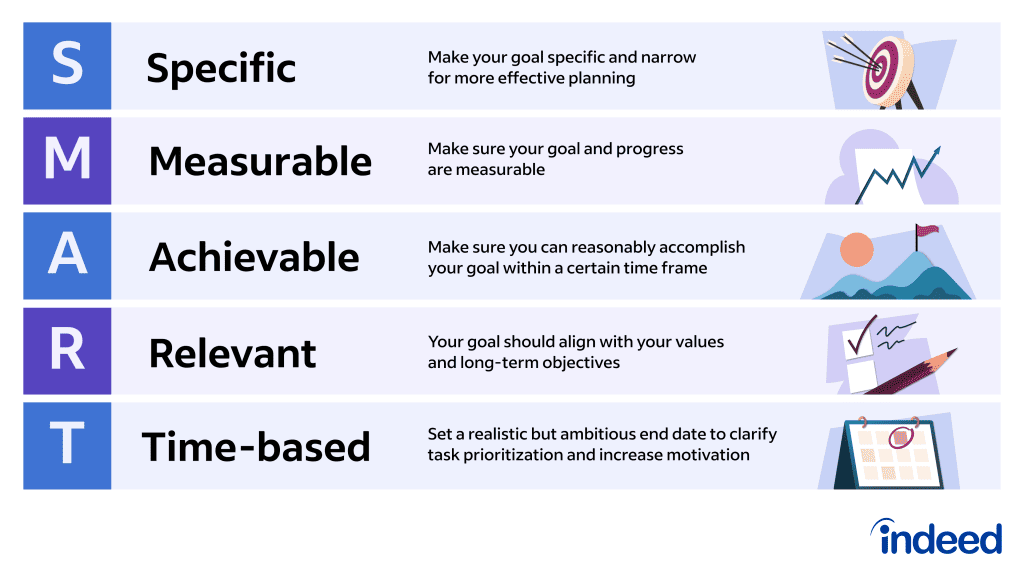

- S stands for specific. Do your learning objectives outline skills that you are able to measure? If they're too broad, you might want to revamp them.

- M stands for measurable. Your objectives should be able to be measured in classroom setting, through testing or observed performances.

- A stands for action-oriented. All educational objectives should include action verbs that call for the performance of a specific task.

- R stands for reasonable. Make sure your learning objectives reflect realistic expectations of your students given the timeframe of your course. For example, you can't expect students to learn something like CPR by the end of a week-long unit.

- T stands for time-bound. All educational objectives should outline a specific timeframe they need to be met by.

- Obviously, tests, papers, exams, and quizzes throughout the semester effectively measure if educational objectives are being met. If one students seem to be struggling with an objective, it might be an issue of that individual's performance. If every student seems to struggle, however, you may not be effectively relaying the information.

- Give your students questionnaires and surveys in class, asking them how they feel about their own knowledge of a given subject. Tell them to be honest about what you're doing right and wrong as a teacher.

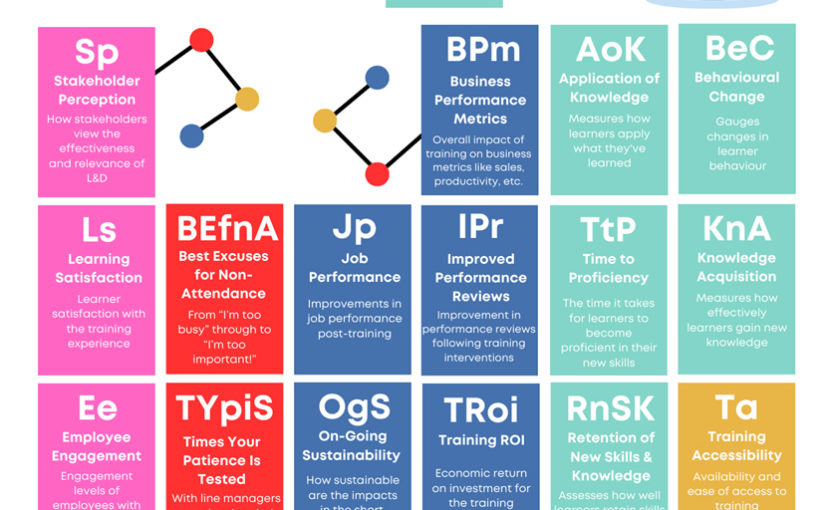

Sample Objectives and Things to Include and Avoid

Community Q&A

- Fellow educators can help you with your objectives. Everyone in the world of education has to write educational objectives. If you are struggling, have a peer review your objectives and give you feedback. Thanks Helpful 8 Not Helpful 0

- Look at lots of examples of educational objectives. They are usually listed in course syllabi. This will give you a sense of what a solid, well written objective sounds like. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 6

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://rapidbi.com/the-difference-between-goals-objectives/

- ↑ https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/taxonomies-educational-objectives

- ↑ https://fctl.ucf.edu/teaching-resources/course-design/blooms-taxonomy/

- ↑ https://www.yourcoach.be/en/coaching-tools/smart-goal-setting.php

About This Article

To write an educational objective, create stem statements that outline what you expect from your students. Use a measurable verb like "calculate" or "identify" to relay each outcome, which is what the students are expected to do at the end of a course or lesson. Be sure to define a time frame for each objective in your stem statements, and don't forget to note the criteria you plan to use to evaluate the students! For tips on using Bloom's Taxonomy when creating an educational objective, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mar 10, 2018

Did this article help you?

Elangovan Arumugam

Oct 18, 2020

Dec 21, 2016

Burtay Hatice Ince

Mar 23, 2017

Maureen Joseph

May 20, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Part 1: The Basics of Lesson Planning

How to: writing objectives.

- Before beginning this section, be sure to read this section: Foundational Understanding: Learning Standards and Foundational Understanding: DOK .

The Five rules of writing objectives

Rule #1: All objectives are one sentence long and start with “The student will…” or “The learner will…”

Rule #2 : All objectives contain one Bloom’s Taxonomy verb. Bloom’s Taxonomy verbs are necessary for an objective. It allows for the objective to be assessed. This resource offers a good overview of how Bloom’s Taxonomy verbs work.

Rule #3 : The objective needs to be tied to a state standard.

Rule #4 : The objective needs to indicate a DOK level.

Rule #5 : An objective should typically have one topic. It is always better to make two separate objectives rather than one objective that will measure two things.

Anatomy of an Objective

Locating the Mississippi State Standards

The State of Mississippi has content standards for every subject and grade level . They are called “College and Career Readiness Standards” and are aligned with Common Core. For the main subject areas (math, science, social studies, and English) there is an app that can be downloaded to a smart phone ( click here for Android ; click here for Apple ).

Writing Objectives, Step by Step

Step 1: write “the student will…”, step 2: find a state standard you wish to cover with the objective..

Add the short-hand abbreviation to the end of the objective. For example, let’s say you are teaching Geometry, and want to use standard “G-GMD.3: Use volume formulas for cylinders, pyramids, cones, and spheres to solve problems.” This standard covers several shapes, so our objective will need to be a little more specific. Since the objective will be tied to the standard, we would add “G-GMD.3” to the very end of the objective.

At this point, your objective should look something like “ The student will…(G-GMD.3) ”

Step 3: Choose a Bloom’s Taxonomy verb.

Continuing with the geometry example, this topic lends itself to students applying a formula to solve a problem. Therefore, it makes sense to pull a verb from the “apply” category. In this case, there are several potential verbs: solve, implement, use, compute , and apply . For the sake of this example, the Bloom’s Taxonomy verb solve will be used.

At this point, your objective should look something like “ The student will solve… (G-GMD.3) ”

Step 4: Decide on the topic covered.

Be as specific and direct as you can. In this case, the word “problems” and “pyramids” will be pulled straight from the state standard.

At this point, your objective should look something like “ The student will solve word problems using the volume formula for pyramids. (G-GMD.3) ”

Step 5: Add the appropriate DOK level.

Add the appropriate DOK level based on the charts from that section. In this case, students are applying a formula (what could be considered a “skill”) to find an answer. Therefore, this objective would fall into a DOK 2 because students are “applying skills and concepts.”

Now, your finished objective should look as follows: “ The student will solve word problems using the volume formula for pyramids. (DOK 2) (G-GMD.3) ”

Other thoughts

The objective writing process requires you to consider at least two other questions: “What do the students already know?” and “What objectives support and/or complement this objective?”

What do the students already know?

The objective written above assumes that students are already familiar with the volume formula for pyramids. However, if they have never been exposed to this formula, we will need to teach the students that before we attempt this objective. Gaining an understanding of what students know is part of the assessment process, which will be covered in that section of this text.

“What objectives support and/or complement this objective?”

This objective covers pyramids, but there are other shapes mentioned in the standard. Please resist the temptation to cover an entire standard in one objective. Remember, an objective should typically have only one verb and one topic. If one were teaching a series of lessons or a unit, It makes sense that we would have other objectives like the following:

The student will solve word problems using the volume formula for cylinders. (DOK 2) (G-GMD.3) The student will solve word problems using the volume formula for cones. (DOK 2) (G-GMD.3) The student will solve word problems using the volume formula for spheres. (DOK 2) (G-GMD.3)

In addition, notice the objectives have students looking at word problems. There is the possibility that English Language Arts (ELA) objectives might come into play for these lessons. This will be covered in more detail in the cross-curricular section of this text.

Check Out These Free Courses & Discounts >

Learning Objectives: What Are They and How Do I Write Them?

by Model Teaching | August 29, 2018.

Do you sometimes find yourself using the state standard as your learning objective because you are unsure of how to write one yourself? Or maybe you are just leaving them out all together? Find out what information you should be including in your student learning objectives, as well as how you should be using them in your classroom with this article.

Learning Objectives: What Are They & How Do I Write Them?

Have you ever heard the Lewis Carroll quote, “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there”? Have you ever thought about its meaning? Without a direction or knowledge of where you are going, you will always end up in the exact same place – nowhere. This line speaks such truth in education. You can’t know what roads to take, or even know if you have arrived until first you know where you are headed!

Learning objectives are the key component to knowing where you are going. A learning objective is a statement, in specific and measurable terms that describes what the learner will know and be able to do after completing a lesson. When it comes to designing a great unit, or planning out your week of instruction, objective writing should be your first step. Only when you have clear learning objectives can you design activities that make learning engaging and interesting. Without having a solid grasp on what you want your students to know and be able to do, you are left to blindly pick and choose and hope the lesson is successful.

The Three-Part Learning Objective

Every effective learning objective has three main parts: the behavior, the condition, and the criterion. The behavior describes what the learner will be doing. It can be something as simple as matching a word with its definition, or it may be something more challenging such as creating a model. But it must be some form of an observable action verb. You want to avoid words such as “know”, “understand”, or “comprehend”. These actions are unobservable and therefore more difficult to measure mastery. You will also want to have only one verb when writing the behavior portion of your learning objective. Having multiple verbs in an objective can cause confusion when it comes to student mastery. Instead, either write them as two separate objectives, or choose the verb that is at the learning level of your students.

The second component an effective learning objective must contain is the condition. The condition gives specific and clear guidance to the student as to what they can expect when completing the behavior that is stated. For example, it may include specific information the learner will use, such as a specific formula, or it may list the tools or references the student will need in order to complete the behavior such as a dictionary, diagram, or T-chart. Don’t confuse this with the instructional activity or event that is occurring before the learning behavior. For example, “after finishing the book” or “after reading the chapter” is not considered a condition. These phrases do not list the tools or references that will be provided for the actual behavior. Instead they describe what is leading up to the behavior.

The final part of an effective learning objective is the criterion. This is the part of the learning objective that specifically tells the learner what they must do to show mastery of the objective. This can be done in one of three ways: by telling the degree of accuracy the behavior must be performed, by giving a quantity of correct responses that must be given, or by giving a time limit in which the behavior must be completed. Notice the list did not include a grade specific criterion. Grades are not the most effective way to give a student feedback; therefore they should not be used in a learning objective. There may be times when you feel a learning objective needs more than one criterion and that is perfectly acceptable. You may add as many as needed to clarify for students what is expected of them to show mastery.

Tips For Writing Effective Learning Objectives

- Learning objectives should be student-centered. When writing learning objectives, make sure the focus is always on the student. They should always describe what the student will be doing, not what you will be teaching or what your instruction will look like. A learning objective should never be confused with a learning activity.

- Make sure to use simple language all learners can understand. Learning objectives should be shared with students prior to the learning. This gives the learner a sense of purpose. Therefore, it is important that they are able to read and understand each word we use.

- Keep the learning objective statement brief. Limiting your objectives to one sentence will help your learners focus better on what is expected of them, instead of becoming discouraged and overwhelmed by the wordiness.

- Match the learning objective to the level of your students. When choosing an action verb for your objective, make sure it is at the same learning level as your students. For example, if you were introducing a new topic to your class, you would want to start them at a lower level and choose a verb such as “describe” or “list”. Using a Bloom’s Taxonomy verb chart can help with this.

- Write objectives with outcomes in mind – not content. Your focus should be entirely on what a student should be able to do, not on the lesson itself. The lesson will develop out of the outcome, not the other way around. Remember, you need to know where you are going before you can choose your path to get there.

After writing your learning objectives, use a checklist like the one included to carefully examine each one. In order for an objective to be the most effective, it must meet each and every criteria.

Sharing Learning Objectives With Students

How many of us have written a learning objective on the board only because we are required to do so, and never do anything with it? I bet there are quite a few of us. We are missing out on a huge opportunity to improve student learning in the classroom when we do this. Learning objectives shape what students learn. When a student knows before hand what they are expected to learn, they are able to direct their attention towards those particular areas. There is a sense of purpose for their learning.

The most important step of sharing learning objectives is to ensure students actually understand the objective. One way we can do this is by engaging students in a discussion about the learning objective prior to the lesson. Ask questions such as:

- What are we going to be learning today?

- How does this relate to something we have already learned?

- Why do you think it is important that we learn this?

- When do you think we would use this in the real world?

- How will you know if you have got it?

This gives students the opportunity to stop and process the information found in the objective. Classrooms where students understand the learning objective for the daily lesson see performance rates that are 20% higher than those where the learning objective is either unknown or unclear. (Marzano, 2003)

Now that you know what goes in to writing an effective learning objective and how to share it with your students, I challenge you to start each planning session with writing learning objectives. Let this guide the planning of your lessons. Then consistently start each lesson discussing the objective with your class. You will begin to see a change in student learning in your classroom.

Related Professional Development Courses:

Writing Effective Learning Objectives

Efficient Classroom Processes

Measuring Growth in Writing Using Rubrics (Gr K-3)

(8 PD Hours) Learn what typical writing looks like for kindergarten through third-grade students, as well as some common writing tasks they can be expected to accomplish and learn the purpose of both holistic and analytic rubrics for writing assessment.

All Blog Topics

Classroom Management

- English Language Learners (ELL)

Gifted & Talented

Leadership Development

Lesson & Curriculum Planning

Math Instruction

Parent Involvement

Reading/ELA Instruction

Science Instruction

Social/Emotional Learning

Special Education

Teaching Strategies

Technology In The Classroom

Testing Strategies & Prep

Writing Instruction

DOWNLOADS & RESOURCES

Learning Objective Checklist

Use this checklist to help you write your learning objective.

IMPLEMENTATION GOAL

Choose one subject area that you teach and start your next planning session by writing your learning objectives before deciding what lessons or activity you will be using. Use the downloadable checklist to check your objectives for effectiveness. Use these objectives to build your lessons off of for the week. Then each day start your lesson by discussing the objective with your class. Use the questions found in this article to lead the discussion. Do it for two weeks before adding in another subject area.

Share This Post With Friends or Colleagues!

Your shopping cart.

The cart is empty

Search our courses, blogs, resources, & articles.

- Teaching Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Writing Learning Objectives: Definitions, Strategies and Examples

Simple steps to writing effective, measurable learning objectives for university and college educators. This guide includes practical approaches and helpful examples.

Top Hat Staff

While it’s natural to focus on theory and concepts when designing your course, it’s equally important to think about the net result you want to achieve in terms of student learning. Learning objectives focus on just that—they articulate what students should be able to know, do and create by the end of a course. They’re also the key to creating a course in which courseware, context, teaching strategies, student learning activities and assessments all work together to support students’ achievement of these objectives.

This guide presents essential information about how to write effective, measurable learning objectives that will create a strong structure and instructional design for your course.

Table of contents

What are learning objectives, learning objectives vs. learning outcomes, how to write learning objectives, tools for developing effective learning objectives, examples of learning objectives.

Learning objectives identify what the learner will know and be able to do by the end of a course. Grounded in three primary learning areas—attitudes, skills and knowledge—clear learning objectives help organize student progress throughout the curriculum .

While the terms “learning objectives” and “learning outcomes” are often used interchangeably, there are subtle differences between them.

One key distinction is that learning objectives are a description of the overarching goals for a course or unit. Learning outcomes , on the other hand, outline goals for the individual lessons comprising that course or unit. Learning outcomes should be measurable and observable, so students can gauge their progress toward achieving the broader course objectives.

Another distinction between the two concepts is that learning objectives focus on the educator or institution’s educational goals for the course. For students, goals and progress in a specific course or program are measured by learning outcomes.

Learning objectives help students understand how each lesson relates to the previous one. This way, students can understand how each course concept relates to the course’s goals, as well as degree or course goals. When writing measurable student learning objectives, instructors should ensure that they are structured in a way that makes it easy for students to assess their own progress, as well as the way forward in their learning.

Strong learning objectives should:

- Focus on what students should learn in a course rather than what the instructor plans to teach

- Break down each task into an appropriate sequence of skills students can practice to reach each objective

- Make use of action-oriented language

- Be clear and specific so students understand what they will learn and why they are learning it

Learning objectives should also be measurable. In order to be effective, they must lay out what success looks like. This way, students can accurately gauge their progress and performance. From these criteria, students should be able to clearly identify when they have completed an element of the course and are ready to move on to the next one.

Key elements to consider

By answering certain fundamental questions, you can begin the process of developing clear learning objectives armed with the information to craft them effectively.

- Which higher-order skills or practical abilities do you want students to possess after attending your course that they did not possess beforehand?

- What do your students need to know and understand in order to get from where they are now to where you want them to be by the end of the course?

- Which three main items do you want students to take away from your course if they learn nothing else?

3 steps to writing learning objectives

Writing strong and effective learning objectives is a matter of three simple steps:

- Explain the precise skill or task the student will perform.

- Describe how the student will execute the given skill or task and demonstrate relevant knowledge and competency—a quiz, test, group discussion, presentation, research project.

- Lay out the specific criteria you will use to measure student performance at the end of the learning experience.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

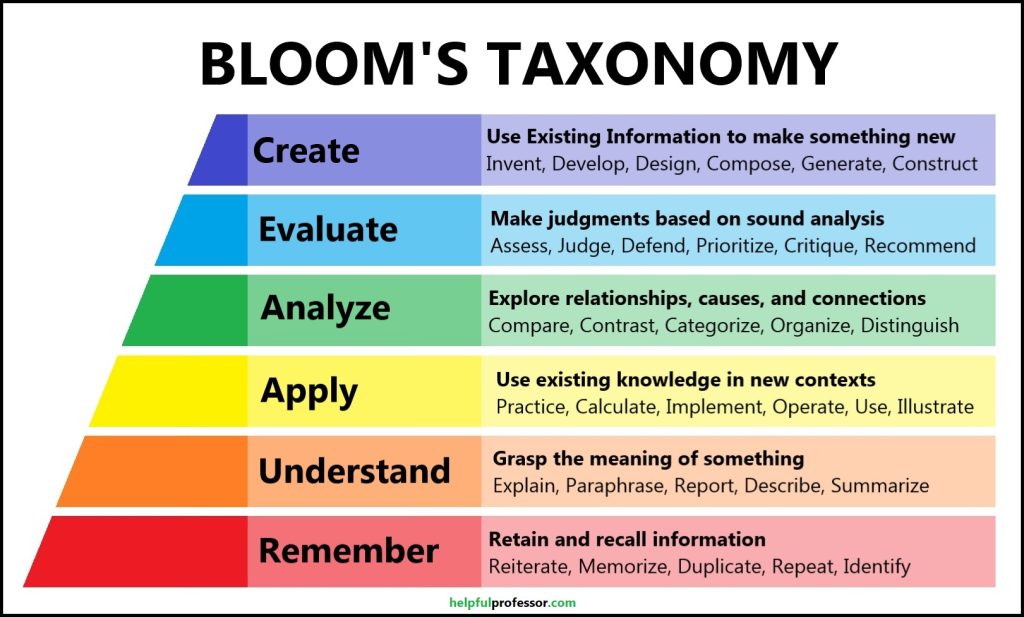

Used to develop effective learning objectives, Bloom’s Taxonomy is an educational framework that is designed to help educators identify not only subject matter but also the depth of learning they want students to achieve. Then, these objectives are used to create assessments that accurately report on students’ progress towards these outcomes.

The revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001) comprises three domains—cognitive, affective and psychomotor. In creating effective learning objectives, most educators choose to focus on the cognitive domain. The cognitive domain prioritizes intellectual skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creating a knowledge base. The levels of this domain span from simple memorization designed to build the knowledge of learners, to creating a new idea or working theory based on previously learned information. In this domain, learners are expected to progress linearly through the levels, starting at “remember” and concluding at “create,” in order to reach subject mastery.

The following are the six levels of the cognitive domain:

- Remembering

- Understanding

Action verbs

These action verbs and sample learning objectives are mapped to each level of Bloom’s Taxonomy’s cognitive domain. Here, we provide a breakdown of how to implement each level in your classroom. Some examples of action verbs useful for articulating each of the levels within the cognitive domain include:

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of a geography workshop, students will be able to list the different layers of rock in a given natural structure.

- Sample learning objective: By the end of a Sociology lesson, students will be able to identify instruments for collecting data and measurements for the conducting and planning of research.

- Sample learning objective: After a lesson on literary analysis, students will be able to assign a cohesive reading list for an imagined class on a particular subtopic within the literary realm.

- Sample learning objective: At the end of a course in global economics, students will be able to analyze the economic theories behind various macroeconomic policies and accurately categorize them.

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of a course on the history of war, students will be able to compare and contrast any two historic wars using timelines of the respective conflicts.

- Sample learning objective: Upon completion of the astronomy course, students will be able to predict the motion and appearance of celestial objects and curate data on the subject from multiple sources and communicate procedures, results and conclusions properly.

The SMART strategy

Simply put, learning objectives are goals for teaching and learning. They provide a sense of direction, motivation and focus. By setting objectives, you can provide yourself and your students with a target to aim for. A straightforward way to set realistic, achievable expectations is through the SMART strategy, ensuring objectives are:

- Specific : Unambiguous, well-defined and clear.

- Measurable : Designed with specific criteria of how to measure your progress toward the accomplishment of the goal in mind.

- Achievable : Attainable and possible to achieve.

- Realistic : Within reach, realistic, and relevant to the course or program’s purpose.

- Timely : With a clearly defined timeline, including a starting date and a target date, to ensure you can set mini-milestones and check-ins throughout the duration of your course.

By writing measurable learning objectives you can better choose and organize content and use that to select the most appropriate instructional strategies and assessments to meet the learning goals for your course.

- Using language formally vs. informally

- Explaining how to write and speak in each type of language

- Teaching others how to choose and use the appropriate type of language in different situations

- Good example: Upon completion of this course, students will possess the ability to identify and develop instruments for collecting data and measures for executing academic research.

- Poor example: After completing this course, students will be able to explain the organizational structure.

- Poor example: Students will comprehend the importance of the Civil War.

The first two are good learning objectives because they explain the exact skill or task the student will perform, as well as how they will be tested and evaluated on their performance. The second examples are poor because they are vague and do not include how the knowledge acquired will be evaluated.

Student learning improves when they know what is expected of them. When learning objectives are clear, students are better prepared for a deeper approach to learning. This means that students seek meaning, relate and extend ideas, look for patterns and underlying principles, check evidence, examine arguments critically and engage with course content in a more sophisticated way.

For instructors, this means a more engaged and connected classroom community that works together. By setting clear guidelines for what you intend to teach and for students to learn, you can ensure that you are laying the foundation for a successful and more motivating educational experience.

Hattie, J. A. C., & Donoghue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model. Science of Learning , 1, 1–13. doi:10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13

Marsh, P.A. (2007). What is known about student learning outcomes and how does it relate to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning? International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 1(2), article 22.

Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (1991). Improving the quality of student learning: the influence of learning context and student approaches to learning on learning outcomes. Higher Education , 22(3), 251–266.

Recommended Readings

The Ultimate Guide to Metacognition for Post-Secondary Courses

25 Effective Instructional Strategies For Educators

Subscribe to the top hat blog.

Join more than 10,000 educators. Get articles with higher ed trends, teaching tips and expert advice delivered straight to your inbox.

The Innovative Instructor

Pedagogy – best practices – technology.

Writing Effective Learning Objectives

Developing learning objectives is part of the instructional design framework known as Backward Design, a student-centric approach that aligns learning objectives with assessment and instruction.

Clearly defined objectives form the foundation for selecting appropriate content, learning activities and assessment plans. Learning objectives help you to:

- plan the sequence for instruction, allocate time to topics, assemble materials and plan class outlines.

- develop a guide to teaching allowing you to plan different instructional methods for presenting different parts of the content. (e.g. small group discussions of a common misconception).

- facilitate various assessment activities including assessing students, your instruction, and the curriculum.

Think about what a successful student in your course should be able to do on completion. Questions to ask are: What concepts should they be able to apply? What kinds of analysis should they be able to perform? What kind of writing should they be able to do? What types of problems should they be solving? Learning objectives provide a means for clearly describing these things to learners, thus creating an educational experience that will be meaningful.

Following are strategies for creating learning objectives.

I. Use S.M.A.R.T. Attributes

Learning objectives should have the following S.M.A.R.T. attributes.

S pecific – Concise, well-defined statements of what students will be able to do. M easurable – The goals suggest how students will be assessed. Start with action verbs that can be observed through a test, homework, or project (e.g., define, apply, propose). A ttainable – Students have the pre-requisite knowledge and skills and the course is long enough that students can achieve the objectives. R elevant – The skills or knowledge described are appropriate for the course or the program in which the course is embedded. T ime-bound – State when students should be able to demonstrate the skill (end of the course, end of semester, etc.).

II. Use Behavioral Verbs

Another useful tip for learning objectives is to use behavioral verbs that are observable and measurable. Fortunately, Bloom’s taxonomy provides a list of such verbs and these are categorized according to the level of achievement at which students should be performing. (See The Innovative Instructor post: A Guide to Bloom’s Taxonomy ) Using concrete verbs will help keep your objectives clear and concise.

Here is a selected, but not definitive, list of verbs to consider using when constructing learning objectives:

assemble, construct, create, develop, compare, contrast, appraise, defend, judge, support, distinguish, examine, demonstrate, illustrate, interpret, solve, describe, explain, identify, summarize, cite, define, list, name, recall, state, order, perform, measure, verify, relate

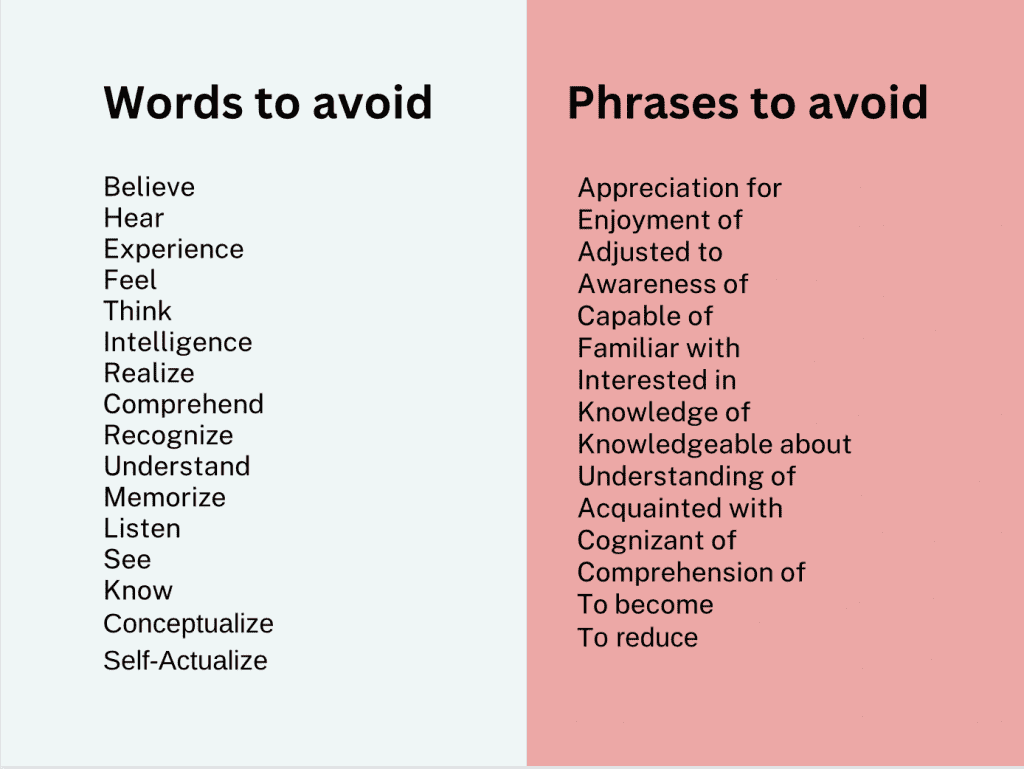

While the verbs above clearly distinguish the action that should be performed, there are verbs to avoid when writing a learning objective. The following verbs are too vague or difficult to measure:

appreciate, cover, realize, be aware of, familiarize, study, become acquainted with, gain knowledge of, comprehend, know, learn, understand, learn

III. Leverage Bloom’s Taxonomy

Since Blooms taxonomy establishes a framework for categorizing educational goals, having an understanding of these categories is useful for planning learning activities and writing learning objectives.

Examples of Learning Objectives

At end of the [module, unit, course] students will be able to…

… identify and explain major events from the Civil War. (American History)

… effectively communicate information, ideas and proposals in visual, written, and oral forms. (Marketing Communications)

… analyze kinetic data and obtain rate laws. (Chemical Engineering)

…interpret DNA sequencing data. (Biology)

…discuss and form persuasive arguments about a variety of literary texts produced by Roman authors of the Republican period. (Classics)

…evaluate the appropriateness of the conclusions reached in a research study based on the data presented. (Sociology)

…design their own fiscal and monetary policies. (Economics)

Additional Resources

- Bloom, B., Englehart, M. Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain . New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green.

- Writing learning objectives. http://sites.uci.edu/medsim/files/2015/03/Writing-learning-objectives.pdf

*****************************************************************************************

Richard Shingles, Lecturer, Biology Department

Richard Shingles is a faculty member in the Biology department and also works with the Center for Educational Resources at Johns Hopkins University. He is the Director of the TA Training Institute and The Summer Teaching Institute on the Homewood campus of JHU. Dr. Shingles also provides pedagogical and technological support to instructional faculty, post-docs and graduate students.

Images source: © Reid Sczerba, Center for Educational Resources, 2016

19 thoughts on “ Writing Effective Learning Objectives ”

The post is interesting. Can I share it?

Yes you may, just please link back.

I agree! Perfect to help my pre-service teachers! Thank you.

Pingback: English Language Arts and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Infoshop – Critical Education and TESOL

From the viewpoint of SPECIFIC , isn’t it that singularity of behavior that can be measured rather than two behaviors at the same time as noted in your example “Identify and explain” is more preferable. I think combining two behaviors at the same time defeats the purpose of concise

Pingback: How to Successfully Earn from Online Courses - GoEdu

I agree with separating the two behaviors into two learning objective statements.

Thanks for the concrete suggestions for writing course objectives.

Quite helpful due to such clear explanations. Thanks.

I am especially drawn by the list of verbs and verbal expressions not to use in preparing learning objectives, some of which I had not considered but these expressions do express a level of noncommittal and ambiguity. This is useful information

I really appreciate this article, it has really helped me a lot. I will take what I learned from this article and apply the knowledge for when I create the online classes for the fall 202 semester and further into the future.

This was an excellent article. I appreciated both lists of verbs. The lists will help me in the future, and they’re a great resource to continually use.

Thank You for the clear and concise information.

Very good article on specific terms that identify what is required from the students.

I first learned of Bloom’s taxonomy when I took Applying the QM Rubric. This is a great guide to help me with articulating learning objectives and creative module and course level objectives.

Helpful to have specific examples in different content areas, thanks!

I appreciated the differences between concrete verbs and vague verbs.

Excellent description of what we should be listing for the students. In the pass, our objectives were vague and not always measurable other than quizzes, tests, written assignments, and exams. This proposal assures that each objective can be measured and provides the students how to determine their understanding and grasp of the materials and requirements.

Thank You: I enjoyed reading this, it was very helpful, I do plan to utilize it. Also, the GoEd, Article, How to successfully learn from Online courses, is broken, it returns as an error

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

55 Learning Objectives Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

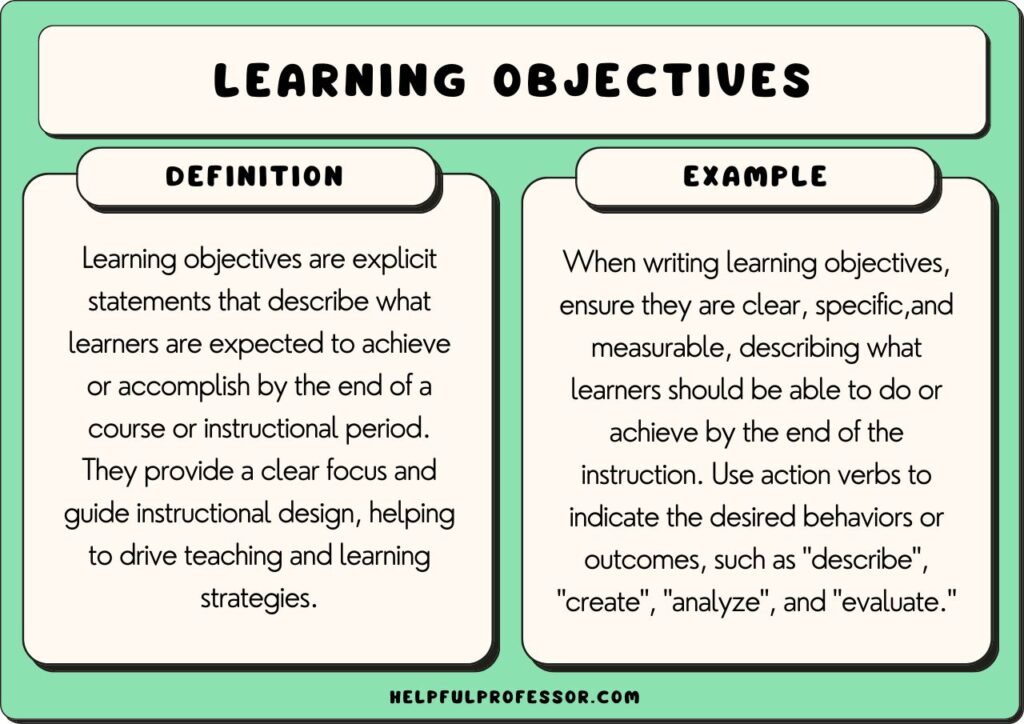

Learning objectives are explicit statements that clearly express what learners should be able to comprehend, perform or experience by the end of a course or instructional period (Adams, 2015).

They are fundamental to the process of educational planning and instructional design, acting as vehicles that drive both teaching and learning strategies.

Importantly, they ensure coherence and a clear focus, differentiating themselves from vague educational goals by generating precise, measurable outcomes of academic progress (Sewagegn, 2020).

I have front-loaded the examples in this article for your convenience, but do scroll past all the examples for some useful frameworks for learning how to write effective learning objectives.

Learning Objectives Examples

| Subject Area | Learning Objective | Verbs Used |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Skills | “By the end of the communication skills course, learners should be able to a five-minute persuasive speech on a topic of their choice, clear language and effective body language.” | , |

| Chemistry | “Upon completion of the chemical bonding module, learners will Lewis structure diagrams for 10 common molecules.” | |

| Psychology | “By the end of the course, students should be able to the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy to three case studies, and the likely outcomes of such therapies.” | , |

| Mathematics | “On completion of the statistics unit, learners will be able to standard deviation for a given data set with at least 95% accuracy.” | |

| Computer Programming | “After eight weeks of the intermediate Python program, learners will and a fully-functioning game Pygame library.” | , |

| History | “After studying the Civil War unit, students will a 1500-word essay the major causes of conflict between the North and South, at least five primary sources.” | , |

| Foreign Language | “By the end of level one French, learners will 20 common regular and irregular verbs in present tense in a written quiz.” | |

| Marketing | “At the end of the course, students will a complete marketing plan for a new product, market research, SWOT analysis, and a marketing strategy.” | , |

| Nursing | “Upon completing the pediatric coursework, nursing students will proper techniques for vital signs in infants and toddlers during simulation labs.” | , |

| Art | “By the end of the introductory drawing course, learners will a portfolio containing at least five different still life drawings, mastery of shading techniques.” | , |

| Nutrition | “Participants will five key differences between plant-based and animal-based proteins by the end of the session.” | |

| Education Policy | “Students will the impact of No Child Left Behind policy on student performance in a final course essay.” | |

| Literature | “Learners will symbolic elements in George Orwell’s 1984, a 2000-word essay.” | , |

| Biology | “Upon completion of the genetics module, pupils will the process of DNA replication in a written test.” | |

| Music | “By the end of the semester, students will a chosen piece from the Romantic period on their main instrument for the class.” | |

| Physics | “Upon completion of the Quantum Physics course, students will the two-slit experiment wave-particle duality theory.” | , |

| Economics | “Learners will Keynesian and Classical economic theories, the main disagreements between the two in a PowerPoint presentation.” | , |

| Fitness Coaching | “Participants will personalized long-term workout plans, their fitness level and goals, by the end of the course.” | , |

| Criminal Justice | “Students will key components of an effective rehabilitation program for juvenile offenders in a group presentation.” | |

| Philosophy | “Learners will principles from three philosophical movements studied during the course.” | , |

| Geography | “By course-completion, students will and the impact of climate change on five major global cities.” | , |

| Environmental Science | “Students will an experiment to air pollution levels in different areas of the city, their findings in a lab report.” | , , |

| Sociology | “After studying social stratification, learners should be able to various social behaviors and phenomena into different social classes.” | |

| Dance | “Learners will a three-minute dance routine at least five different dance moves learned during the course.” | , |

| Culinary Arts | “Students will a five-course French meal, the cooking techniques and recipes studied throughout the program.” | , |

Learning Objectives for Internships

| Subject Area | Learning Objective | Verbs Used |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Internship | “I will and a mini, digital marketing campaign for a new product, my social media marketing skills.” | , , |

| Engineering Internship | “My objective is to in the development of a new product prototype, my CAD software skills.” | , |

| Psychology Internship | “I aim to literature reviews on at least five recent articles related to cognitive behavior therapy, my research and analytic skills.” | , |

| Finance Internship | “I intend to different investment portfolios and my findings, my financial analysis skills.” | , , |

| Hospitality Internship | “During my intern period, I will an event at the hotel, on developing my event planning and operation skills.” | , |

| Legal Internship | “I plan to five recent court case outcomes related to environmental law, my legal research skills.” | , |

| Journalism Internship | “By the end of my internship, I will and two articles in the local news section, my journalistic writing skills.” | , , |

| Healthcare Internship | “My goal is to patient medical histories and vital signs, my clinical and interpersonal skills.” | , |

| Public Relations Internship | “I seek to and a press release for a new branch launch, my corporate communication skills.” | , , |

| Human Resources Internship | “I aim to in the hiring process of a new team, including CV screening and interview coordination, my personnel selection skills.” | , |

For more, see: List of SMART Internship Goals

Learning Objectives for Presentations

| Subject Area | Learning Objective | Verbs Used |

|---|---|---|

| Motivational Talk | “In my presentation, I aim to the audience by a personal experience of overcoming adversity, my storytelling skills.” | , , |

| Business Proposal | “I will a compelling business model presentation, my skills in business communication and critical analysis.” | , |

| Research Presentation | “I intend to my research findings and implications, thus my abilities in research communication.” | , |

| Book Report | “My objective is to an insightful analysis of a chosen book, my literary works.” | , |

| Cultural Awareness | “I will significant cultural norms and values of a specific culture, cultural understanding and my skills in intercultural communication.” | , , |

| Product Demo | “I aim to the features and uses of a product, my ability to engage and inform potential customers.” | , |

| Environmental Advocacy | “In my presentation, I intend to for sustainable , my skills in persuasive communication.” | , |

| Training Workshop | “I’m aiming to participants in a new skill or process, my capabilities in instructional presentation.” | , |

| Startup Pitch | “I plan to a compelling startup pitch that includes progress, financial projections, and investment opportunities, thus my skills in business pitching.” | , |

| Health and Wellness Seminar | “I want to practical methods for stress management to my audience, my skills in presenting health-related topics.” | , |

For More: See This Detailed List of Communication Objectives Examples

Learning Objectives for Kindergarten

| Subject Area | Learning Objective | Verbs Used |

|---|---|---|

| Language Arts | “Students will and all 26 letters of the alphabet before the end of the first semester.” | , |

| Numeracy | “By the end of the second semester, children will from 1 to 50 without assistance.” | |

| Social Studies | “Kindergarteners will three different community helpers (like firefighters, doctors, and teachers) and their roles.” | , |

| Science | “Children will between animals and plants by pictures of living things.” | , |

| Physical Education | “By the second marking period, students will basic rules of an organized game such as ‘Duck, Duck, Goose’.” | |

| Arts | “Learners will a self-portrait using colors, shapes, and lines through given art supplies.” | |

| Phonics | “At year-end, learners should three-letter words using learned phonics sounds.” | |

| Reading | “Students will a 5-sentence paragraph from a beginner reader book to the class.” | , |

| Writing | “Learners will their own name without assistance by the end of the kindergarten year.” | |

| Mathematics | “Kindergarteners will objects based on characteristics such as shape, size, or color.” |

Taxonomies to Assist in Creating Objectives

Various taxonomies are available to educators as guides in formulating potent learning objectives, with three prominent ones provided below.

1. The SMART Framework for Learning Objectives

The SMART framework helps you to construct clear and well-defined learning objectives. It stands for: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (Doran, 1981).

- Specific objectives are ones that are straightforward, detailing the what, why, and how of the learning process. For example, an objective that states “Improve mental multiplication skills” is less specific than “Multiply two-digit numbers mentally within two minutes with 90% accuracy.” When I was learning to write learning objectives at university, I was taught to always explicitly describe the measurable outcome .

- Measurable objectives facilitate tracking progress and evaluating learning outcomes. An objective such as “Write a 500-word essay on the causes of World War II, substantiated with at least three academic sources” is measurable, as both word count and the number of sources can be quantified.

- Achievable objectives reflect realistic expectations based on the learner’s potential and learning environment, fostering motivation and commitment.

- Relevant objectives correspond with overarching educational goals and learner’s needs, such as an objective to “identify and manage common software vulnerabilities” in a cybersecurity course.

- Time-bound objectives specify the duration within which the learning should take place, enhancing management of time and resources in the learning process.

2. Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s taxonomy outlines six cognitive levels of understanding – knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Adams, 2015). Each are presented below:

Each level is demonstrated below:

| Level of Learning (Shallow to Deep) | Description of Learning | Verbs to Use in your Learning Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Remember | Retain and recall information | Reiterate, memorize, duplicate, repeat, identify |

| Understand | Grasp the meaning of something | Explain, paraphrase, report, describe, summarize |

| Apply | Use existing knowledge in new contexts | Practice, calculate, implement, operate, use, illustrate |

| Analyze | Explore relationships, causes, and connections | Compare, contrast, categorize, organize, distinguish |

| Evaluate | Make judgments based on sound analysis | Assess, judge, defend, prioritize, critique, recommend |

| Create | Use existing information to make something new | Invent, develop, design, compose, generate, construct |

Here, we can reflect upon the level of learning and cognition expected of the learner, and utilize the Bloom’s taxonomy verbs to cater the learning objectives to that level.

3. Fink’s Taxonomy

Another helpful resource for creating objectives is Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning , which emphasizes different dimensions of learning, including foundational knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn (Marzano, 2010):

- Foundational knowledge refers to the basic information learners must understand to progress with the topic at hand—for instance, understanding color theory before painting a canvas.

- Application gives learners real-world instances for applying the knowledge and skills they’ve cultivated, such as using Adobe Photoshop in a design project after a graphic design lecture.

- Integration enables learners to make interdisciplinary connections between the new knowledge and various fields of study or areas of life—for example, a business student applying economic theory to understand market dynamics in biotechnology.

- Human dimension involves personal and social implications of learning, i.e., how the learners see themselves and interact with others in light of the new knowledge.

- Caring challenges learners to develop new feelings, interests, or values aligned with the course outcomes, like fostering a conservation mindset in an environmental science course.

- Learning how to learn encourages learners to become self-directed and resourceful, enabling them to cultivate learning strategies, skills, and habits that make them lifelong learners, such as using reflective journals or peer reviews (Marzano, 2010).

An example of an objective that uses Fink’s framework could be:

“Learners will conduct a small research project about a famous physicist (foundational knowledge), incorporating class teachings (application) and their own interpretations (integration), then present to the class (human dimension), reflecting on how the physicist’s work affects them personally (caring) and how the project grew their understanding of research methods (learning how to learn).”

Why are Learning Objectives Important?

Effective learning objectives serve to streamline the learning process, creating a clear path for both teachers and learners.

The role of objectives in education mirrors the use of a roadmap on a journey; just as marking out stops and landmarks can facilitate navigation, learning objectives can clarify the trajectory of a course or lesson (Hall, Quinn, & Gollnick, 2018).

On a practical level, imagine teaching a course about climate change. Without explicit learning objectives (like understanding how carbon footprints contribute to global warming), learners could easily veer off track, misinterpreting the main focus.

Learning objectives also act as an anchor during assessments, providing a yardstick against which progress and performance can be gauged (Orr et al., 2022). When students are graduating high school, for example, it’s likely they’ll be assessed on some form of standardized testing to measure if the objectives have been met.

By serving as a guide for content selection and instructional design, learning objectives allow teachers to ensure coursework is suitably designed to meet learners’ needs and the broader course’s objectives (Li et al., 2022). In situations where time is crucial, such as military training or emergency medicine, keeping the focus narrow and relevant is crucial.

Tips and Tricks

1. tips on integrating learning objectives into course design.

Learning objectives serve as a foundation in the designing of a course.

They provide a structured framework that guides the incorporation of different course components, including instructional materials, activities, and assessments (Li et al., 2022).

When designing a photography course, for example, learning objectives guide the selection of appropriate theoretical content (like understanding aperture and shutter speed), practical activities (like a field trip for landscape photography), and the assessment methods (like a portfolio submission).

Just like how research objectives shape the methodology a research study will take, so too will learning objectives shape the teaching methods and assessment methods that will flow-on from the path set out in the overarching learning objectives.

2. Tips on Assessing and Revising your Learning Objectives Regularly

Learning objectives are not set in stone; they demand constant review and refinement.

In the light of feedback from learners, instructors or external bodies (like accreditation agencies), learning outcomes, and advancements in pedagogy, learning objectives may need to be revised (Orr et al., 2022).

Think about a programming course where new frameworks or libraries are regularly introduced; in such cases, the learning objectives would need to be updated to reflect these emerging trends. This provides opportunities for continual enhancement of the course design, thus fostering an environment of progressive learning and teaching (Sewagegn, 2020).

Teachers should revise their learning objectives every time they re-introduce the unit of work to a new cohort of students, taking into account the learnings and feedback you acquired last time you taught the unit.

Learning objectives, when effectively formulated and implemented, serve as key drivers of successful instruction.

They underscore the importance of clarity, directness, and depth in the learning process, fostering a learning environment designed for optimal learner engagement, progress tracking, and educational outcome (Hall, Quinn, & Gollnick, 2018).

With their expansive role in the educational journey, educators are encouraged to invest time and resourceful thought in crafting and continually refining their classroom objectives (Doran, 1981). Moreover, the use of established taxonomies and attention to characteristics like SMARTness in this process can greatly facilitate this endeavor.

As the backbone of well-structured courses, learning objectives deserve the thoughtful consideration and continuous improvement efforts of every dedicated educator. It is our hope that this article has provided insights that will help you bring more clarity, coherence, and effectiveness to your educational planning.

Adams, N. E. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA , 103 (3), 152. doi: https://doi.org/10.3163%2F1536-5050.103.3.010

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’sa SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management review , 70 (11), 35-36.

Hall, G. E., Quinn, L. F., & Gollnick, D. M. (2018). Introduction to teaching: Making a difference in student learning . Sage Publications.

Li, Y., Rakovic, M., Poh, B. X., Gaševic, D., & Chen, G. (2022). Automatic Classification of Learning Objectives Based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. International Educational Data Mining Society .

Marzano, R. J. (2010). Designing & teaching learning goals & objectives . Solution Tree Press.

Orr, R. B., Csikari, M. M., Freeman, S., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2022). Writing and using learning objectives. CBE—Life Sciences Education , 21 (3). Doi: https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.22-04-0073

Sewagegn, A. A. (2020). Learning objective and assessment linkage: its contribution to meaningful student learning. Universal Journal of Educational Research , 8 (11), 5044-5052.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write Learning Objectives: 35 Examples

How do you write learning objectives? This article defines learning objectives for clarity and gives 35 examples of learning objectives.

Table of Contents

Introduction.

Having clear learning objectives is crucial in conducting effective classes. These objectives serve as a roadmap for both educators and learners, outlining the specific knowledge, skills, and competencies that will be covered during the learning experience.

By clearly defining what students are expected to achieve, learning objectives provide a sense of direction and purpose, ensuring that the teaching and learning process remains focused and meaningful.

By setting clear learning objectives, educators can effectively plan their lessons, select appropriate teaching strategies , and design assessments that align with the desired outcomes. Students, on the other hand, benefit from having a clear understanding of what is expected of them, which helps to enhance their motivation, engagement, and overall learning experience.

In the following sections, we will explore various examples of learning objectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of their importance and how they can be effectively utilized in different educational settings.

But first, let’s look at three different definitions of learning objectives.

Learning Objectives Defined

Among these definitions, the most plausible definition for learning objectives, with my little modification to allow measurement, is the first one. This definition emphasizes the importance of specificity, which is crucial for effective teaching and learning.

I added “positive changes” because I believe that after a learning experience, the student must learn something useful or beneficial to advance his or her knowledge, skills, or attitude.

Specific statements that describe what learners should be able to do or positive changes that can be observed and measured after completing a learning experience. P. Regoniel

Therefore, the first definition aligns well with the purpose and function of learning objectives in educational settings.

Learning objectives play a crucial role in guiding the educational process and ensuring that students achieve the desired outcomes. By setting specific and measurable goals , educators can effectively design and deliver lessons that align with the desired learning outcomes .

In this section, I will provide examples of learning objectives in various subject areas, all of which are aligned with the definition of learning objectives chosen in the previous section. These examples comprise the course and their corresponding learning objectives.

1. Principles and Theories of Language Acquisition and Learning

2. human anatomy and physiology, 3. introduction to construction engineering.

Example Learning Objectives

4. Counseling Psychology

5. nutrition and diet therapy, 6. applied statistics, 7. introduction to earth science.

These examples demonstrate the diverse range of learning objectives across different subject areas. Each objective is specific, measurable, and aligned with the chosen definition of learning objectives. By setting clear expectations for what students should be able to do or understand, educators can guide the learning process effectively and ensure that students achieve the desired outcomes.

You may refer to Bloom’s Action Verbs as your guide in writing measurable learning objectives.

Learning objectives serve as a roadmap for both educators and students, outlining the expected outcomes of the learning process. By setting specific and measurable goals, educators can design and deliver lessons that align with these objectives. This helps to ensure that students gain the knowledge and skills for success.

The examples provided on how to write learning objectives in the previous sections illustrate how learning objectives can be applied in different subject areas. From principles and theories of language acquisition to human anatomy and physiology, construction engineering, counseling psychology, nutrition and diet therapy, applied statistics, and earth science, each objective is specific, measurable, and aligned with the chosen definition of learning objectives.

Start your class with the end in mind.

Related Posts

Learning effective argument-building through writing an argumentative essay, why are english language proficiency exams important, analyzing the macro and microstructures of editorial texts, about the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a hobbyist writer, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

SimplyEducate.Me Privacy Policy

- Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

- Instructional Guide

Writing Goals and Objectives

“If you’re not sure where you are going, you’re liable to end up some place else.” ~ Robert Mager, 1997

Instructional goals and objectives are the heart of instruction. When well- written, goals and objectives will help identify course content, structure the lecture, and guide the selection of meaningful and relevant activities and assessments. In addition, by stating clear instructional goals and objectives, you help students understand what they should learn and exactly what they need to do.

Course Goals

A course goal may be defined as a broad statement of intent or desired accomplishment. Goals do not specify exactly each step, component, or method to accomplish the task, but they help pave the way to writing effective learning objectives. Typical course goals include a number of subordinate skills, which are further identified and clarified as learning objectives.

A course goal may be defined as a broad statement of intent or desired accomplishment.

For example, an English 102 goal might be to prepare students for English 103. The goal “prepare students” specifies the big picture or general direction or purpose of the course. Course goals often do not specify student outcomes or how outcomes will be assessed. If you have difficulty defining a course goal, brainstorm reasons your course exists and why students should enroll in it. Your ideas can then generate course-related goals. Course goals often originate in the course description and should be written before developing learning objectives. You should also discuss course goals with your colleagues who teach the same class so that you can align your goals to provide students with a somewhat consistent experience of the course.

Course Goal Examples

Marketing course .

Students will learn about personal and professional development, interpersonal skills, verbal and written presentation skills, sales and buying processes, and customer satisfaction development and maintenance.

Physical Geography course

Students will understand the processes involved in the interactions between, spatial variations of, and interrelationships between hydrology, vegetation, landforms, and soils and humankind.

Theatre/Dance course

Students will investigate period style from pre-Egyptian through the Renaissance as it relates to theatrical production. Exploration of period clothing, manners, décor, and architecture with projects from dramatic literature.

General Goal Examples

- Students will know how to communicate in oral and written formats.

- Students will understand the effect of global warming.

- Students’ perspective on civil rights will improve .

- Students will learn key elements and models used in education.

- Students will grasp basic math skills.

- Students will understand the laws of gravity.

Learning Objectives

We cannot stop at course goals; we need to develop measurable objectives. Once you have written your course goals, you should develop learning objectives. Learning Objectives are different from goals in that objectives are narrow, discrete intentions of student performance, whereas goals articulate a global statement of intent. Objectives are measurable and observable, while goals are not.

Comparison of Goals and Objectives

- Broad, generalized statements about what is to be learned

- General intentions

- Cannot be validated

- Defined before analysis

- Written before objectives

Objectives are

- Narrow, specific statements about what is to be learned and performed

- Precise intentions

- Can be validated or measured

- Written after analysis

- Prepared before instruction is designed

Objectives should be written from the student’s point of view

Well-stated objectives clearly tell the student what they must do by following a specified degree or standard of acceptable performance and under what conditions the performance will take place. In other words, when properly written, objectives will tell your learners exactly what you expect them to do and how you will be able to recognize when they have accomplished the task. Generally, each section/week/unit will have several objectives (Penn State University, n.p.). Section/week/unit objectives must also align with overall course objectives.

Well-stated objectives clearly tell the student what they must do ... and under what conditions the performance will take place.

Educators from a wide range of disciplines follow a common learning objective model developed by Heinich (as cited by Smaldino, Mims, Lowther, & Russell, 2019). This guide will follow the ABCD model as a starting point when learning how to craft effective learning objectives.

ABCD Model of Learning Objectives

- A udience: Who will be doing the behavior?

- B ehavior: What should the learner be able to do? What is the performance?

- C ondition: Under what conditions do you want the learner to be able to do it?

- D egree: How well must the behavior be done? What is the degree of mastery?

Writing a learning objective for each behavior you wish to measure is good instructional practice. By using the model as illustrated in Table 2, you will be able to fill in the characteristics to the right of each letter. This practice will allow you to break down more complex objectives (ones with more than one behavior) into smaller, more discrete objectives.

Writing a learning objective for each behavior you wish to measure is good instructional practice.

Behavioral Verbs

The key to writing learning objectives is using an action verb to describe the behavior you intend for students to perform. You can use action verbs such as calculate, read, identify, match, explain, translate, and prepare to describe the behavior further. On the other hand, words such as understand, appreciate, internalize, and value are not appropriate when writing learning objectives because they are not measurable or observable. Use these words in your course goals but not when writing learning objectives. See Verbs to Use in Creating Educational Objectives (based on Bloom’s Taxonomy) at the end of this guide.

Overt behavior: If the behavior is covert or not typically visible when observed, such as the word discriminate, include an indicator behavior to clarify to the student what she or he must be able to do to meet your expectations. For example, if you want your learners to be able to discriminate between good and bad apples, add the indicator behavior “sort” to the objective: Be able to discriminate (sort) the good apples from the bad apples.

Some instructors tend to forget to write learning objectives from the students’ perspective. Mager (1997) contends that when you write objectives, you should indicate what the learner is supposed to be able to do and not what you, the instructor, want to accomplish. Also, avoid using fuzzy phrases such as “to understand,” “to appreciate,” “to internalize,” and “to know,” which are not measurable or observable. These types of words can lead to student misinterpretation and misunderstanding of what you want them to do.

…avoid using fuzzy phrases such as “to understand,” “to appreciate,” “to internalize,” and “to know,” which are not measurable or observable.

The Link Between Learning Objectives and Course Activities and Assessment

After you have crafted your course goals and learning objectives, it is time to design course activities and assessments that will tell you if learning has occurred. Matching objectives with activities and assessments will also demonstrate whether you are teaching what you intended. These strategies and activities should motivate students to gain knowledge and skills useful for success in your course, future courses, and real-world applications. The table below illustrates objective behaviors with related student activities and assessments.

| Level of Learning For Knowledge | Student Activities and Assessments |

|---|---|

| (facts, tables, vocabulary lists) | Self-check quizzes, trivia games, word games Vocabulary test, matching item quiz |

| (concepts) | Have students show examples/non-examples, student-generated flowcharts Equations, word problems with given set of data |

| (rules and principles) | Suggests psychomotor (hands-on) assessments, design projects and prototypes, simulations Checklists, videotape the session |

| or (problem-solving) | Case study, small group critical thinking, teamwork, pair share Essays, research papers, discussion questions |

| (synthesis, create) | Develop a portfolio, design a project Speech, presentation |

Examples of Linked Instructional Goals, Objectives, and Assessments

Instructional goal .

Students will know the conditions of free Blacks during antebellum south.

Learning Objective

In at least 2 paragraphs, students will describe the conditions of free Blacks in pre-Civil War America, including 3 of 5 major points that were discussed in class.

A traditional essay or essay exam.

Instructional Goal

Students will know how to analyze blood counts.

Given a sample of blood and two glass slides, students will demonstrate the prescribed method of obtaining a blood smear for microscopic analysis.