How to Write a Psychology Essay

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Before you write your essay, it’s important to analyse the task and understand exactly what the essay question is asking. Your lecturer may give you some advice – pay attention to this as it will help you plan your answer.

Next conduct preliminary reading based on your lecture notes. At this stage, it’s not crucial to have a robust understanding of key theories or studies, but you should at least have a general “gist” of the literature.

After reading, plan a response to the task. This plan could be in the form of a mind map, a summary table, or by writing a core statement (which encompasses the entire argument of your essay in just a few sentences).

After writing your plan, conduct supplementary reading, refine your plan, and make it more detailed.

It is tempting to skip these preliminary steps and write the first draft while reading at the same time. However, reading and planning will make the essay writing process easier, quicker, and ensure a higher quality essay is produced.

Components of a Good Essay

Now, let us look at what constitutes a good essay in psychology. There are a number of important features.

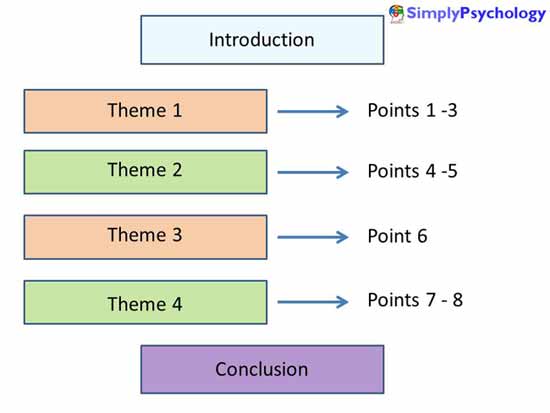

- Global Structure – structure the material to allow for a logical sequence of ideas. Each paragraph / statement should follow sensibly from its predecessor. The essay should “flow”. The introduction, main body and conclusion should all be linked.

- Each paragraph should comprise a main theme, which is illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

- Knowledge and Understanding – recognize, recall, and show understanding of a range of scientific material that accurately reflects the main theoretical perspectives.

- Critical Evaluation – arguments should be supported by appropriate evidence and/or theory from the literature. Evidence of independent thinking, insight, and evaluation of the evidence.

- Quality of Written Communication – writing clearly and succinctly with appropriate use of paragraphs, spelling, and grammar. All sources are referenced accurately and in line with APA guidelines.

In the main body of the essay, every paragraph should demonstrate both knowledge and critical evaluation.

There should also be an appropriate balance between these two essay components. Try to aim for about a 60/40 split if possible.

Most students make the mistake of writing too much knowledge and not enough evaluation (which is the difficult bit).

It is best to structure your essay according to key themes. Themes are illustrated and developed through a number of points (supported by evidence).

Choose relevant points only, ones that most reveal the theme or help to make a convincing and interesting argument.

Knowledge and Understanding

Remember that an essay is simply a discussion / argument on paper. Don’t make the mistake of writing all the information you know regarding a particular topic.

You need to be concise, and clearly articulate your argument. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences.

Each paragraph should have a purpose / theme, and make a number of points – which need to be support by high quality evidence. Be clear why each point is is relevant to the argument. It would be useful at the beginning of each paragraph if you explicitly outlined the theme being discussed (.e.g. cognitive development, social development etc.).

Try not to overuse quotations in your essays. It is more appropriate to use original content to demonstrate your understanding.

Psychology is a science so you must support your ideas with evidence (not your own personal opinion). If you are discussing a theory or research study make sure you cite the source of the information.

Note this is not the author of a textbook you have read – but the original source / author(s) of the theory or research study.

For example:

Bowlby (1951) claimed that mothering is almost useless if delayed until after two and a half to three years and, for most children, if delayed till after 12 months, i.e. there is a critical period.

Maslow (1943) stated that people are motivated to achieve certain needs. When one need is fulfilled a person seeks to fullfil the next one, and so on.

As a general rule, make sure there is at least one citation (i.e. name of psychologist and date of publication) in each paragraph.

Remember to answer the essay question. Underline the keywords in the essay title. Don’t make the mistake of simply writing everything you know of a particular topic, be selective. Each paragraph in your essay should contribute to answering the essay question.

Critical Evaluation

In simple terms, this means outlining the strengths and limitations of a theory or research study.

There are many ways you can critically evaluate:

Methodological evaluation of research

Is the study valid / reliable ? Is the sample biased, or can we generalize the findings to other populations? What are the strengths and limitations of the method used and data obtained?

Be careful to ensure that any methodological criticisms are justified and not trite.

Rather than hunting for weaknesses in every study; only highlight limitations that make you doubt the conclusions that the authors have drawn – e.g., where an alternative explanation might be equally likely because something hasn’t been adequately controlled.

Compare or contrast different theories

Outline how the theories are similar and how they differ. This could be two (or more) theories of personality / memory / child development etc. Also try to communicate the value of the theory / study.

Debates or perspectives

Refer to debates such as nature or nurture, reductionism vs. holism, or the perspectives in psychology . For example, would they agree or disagree with a theory or the findings of the study?

What are the ethical issues of the research?

Does a study involve ethical issues such as deception, privacy, psychological or physical harm?

Gender bias

If research is biased towards men or women it does not provide a clear view of the behavior that has been studied. A dominantly male perspective is known as an androcentric bias.

Cultural bias

Is the theory / study ethnocentric? Psychology is predominantly a white, Euro-American enterprise. In some texts, over 90% of studies have US participants, who are predominantly white and middle class.

Does the theory or study being discussed judge other cultures by Western standards?

Animal Research

This raises the issue of whether it’s morally and/or scientifically right to use animals. The main criterion is that benefits must outweigh costs. But benefits are almost always to humans and costs to animals.

Animal research also raises the issue of extrapolation. Can we generalize from studies on animals to humans as their anatomy & physiology is different from humans?

The PEC System

It is very important to elaborate on your evaluation. Don’t just write a shopping list of brief (one or two sentence) evaluation points.

Instead, make sure you expand on your points, remember, quality of evaluation is most important than quantity.

When you are writing an evaluation paragraph, use the PEC system.

- Make your P oint.

- E xplain how and why the point is relevant.

- Discuss the C onsequences / implications of the theory or study. Are they positive or negative?

For Example

- Point: It is argued that psychoanalytic therapy is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority.

- Explain: Because psychoanalytic therapy involves talking and gaining insight, and is costly and time-consuming, it is argued that it is only of benefit to an articulate, intelligent, affluent minority. Evidence suggests psychoanalytic therapy works best if the client is motivated and has a positive attitude.

- Consequences: A depressed client’s apathy, flat emotional state, and lack of motivation limit the appropriateness of psychoanalytic therapy for depression.

Furthermore, the levels of dependency of depressed clients mean that transference is more likely to develop.

Using Research Studies in your Essays

Research studies can either be knowledge or evaluation.

- If you refer to the procedures and findings of a study, this shows knowledge and understanding.

- If you comment on what the studies shows, and what it supports and challenges about the theory in question, this shows evaluation.

Writing an Introduction

It is often best to write your introduction when you have finished the main body of the essay, so that you have a good understanding of the topic area.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your introduction.

Ideally, the introduction should;

Identify the subject of the essay and define the key terms. Highlight the major issues which “lie behind” the question. Let the reader know how you will focus your essay by identifying the main themes to be discussed. “Signpost” the essay’s key argument, (and, if possible, how this argument is structured).

Introductions are very important as first impressions count and they can create a h alo effect in the mind of the lecturer grading your essay. If you start off well then you are more likely to be forgiven for the odd mistake later one.

Writing a Conclusion

So many students either forget to write a conclusion or fail to give it the attention it deserves.

If there is a word count for your essay try to devote 10% of this to your conclusion.

Ideally the conclusion should summarize the key themes / arguments of your essay. State the take home message – don’t sit on the fence, instead weigh up the evidence presented in the essay and make a decision which side of the argument has more support.

Also, you might like to suggest what future research may need to be conducted and why (read the discussion section of journal articles for this).

Don”t include new information / arguments (only information discussed in the main body of the essay).

If you are unsure of what to write read the essay question and answer it in one paragraph.

Points that unite or embrace several themes can be used to great effect as part of your conclusion.

The Importance of Flow

Obviously, what you write is important, but how you communicate your ideas / arguments has a significant influence on your overall grade. Most students may have similar information / content in their essays, but the better students communicate this information concisely and articulately.

When you have finished the first draft of your essay you must check if it “flows”. This is an important feature of quality of communication (along with spelling and grammar).

This means that the paragraphs follow a logical order (like the chapters in a novel). Have a global structure with themes arranged in a way that allows for a logical sequence of ideas. You might want to rearrange (cut and paste) paragraphs to a different position in your essay if they don”t appear to fit in with the essay structure.

To improve the flow of your essay make sure the last sentence of one paragraph links to first sentence of the next paragraph. This will help the essay flow and make it easier to read.

Finally, only repeat citations when it is unclear which study / theory you are discussing. Repeating citations unnecessarily disrupts the flow of an essay.

Referencing

The reference section is the list of all the sources cited in the essay (in alphabetical order). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms every time you cite/refer to a name (and date) of a psychologist you need to reference the original source of the information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites, then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

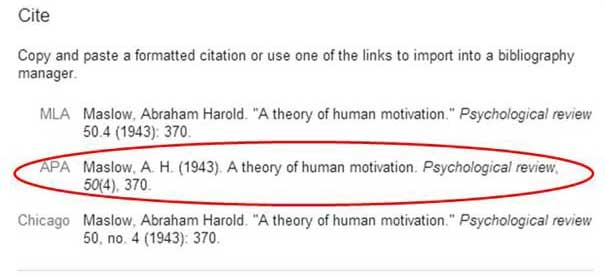

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

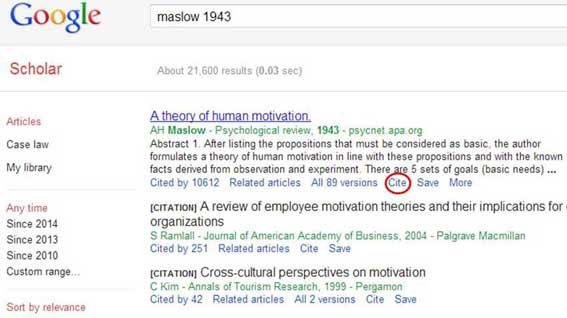

A simple way to write your reference section is use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

What this handout is about

This handout discusses some of the common writing assignments in psychology courses, and it presents strategies for completing them. The handout also provides general tips for writing psychology papers and for reducing bias in your writing.

What is psychology?

Psychology, one of the behavioral sciences, is the scientific study of observable behaviors, like sleeping, and abstract mental processes, such as dreaming. Psychologists study, explain, and predict behaviors. Because of the complexity of human behaviors, researchers use a variety of methods and approaches. They ask questions about behaviors and answer them using systematic methods. For example, to understand why female students tend to perform better in school than their male classmates, psychologists have examined whether parents, teachers, schools, and society behave in ways that support the educational outcomes of female students to a greater extent than those of males.

Writing in psychology

Writing in psychology is similar to other forms of scientific writing in that organization, clarity, and concision are important. The Psychology Department at UNC has a strong research emphasis, so many of your assignments will focus on synthesizing and critically evaluating research, connecting your course material with current research literature, and designing and carrying out your own studies.

Common assignments

Reaction papers.

These assignments ask you to react to a scholarly journal article. Instructors use reaction papers to teach students to critically evaluate research and to synthesize current research with course material. Reaction papers typically include a brief summary of the article, including prior research, hypotheses, research method, main results, and conclusions. The next step is your critical reaction. You might critique the study, identify unresolved issues, suggest future research, or reflect on the study’s implications. Some instructors may want you to connect the material you are learning in class with the article’s theories, methodology, and findings. Remember, reaction papers require more than a simple summary of what you have read.

To successfully complete this assignment, you should carefully read the article. Go beyond highlighting important facts and interesting findings. Ask yourself questions as you read: What are the researchers’ assumptions? How does the article contribute to the field? Are the findings generalizable, and to whom? Are the conclusions valid and based on the results? It is important to pay attention to the graphs and tables because they can help you better assess the researchers’ claims.

Your instructor may give you a list of articles to choose from, or you may need to find your own. The American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO database is the most comprehensive collection of psychology research; it is an excellent resource for finding journal articles. You can access PsycINFO from the E-research tab on the Library’s webpage. Here are the most common types of articles you will find:

- Empirical studies test hypotheses by gathering and analyzing data. Empirical articles are organized into distinct sections based on stages in the research process: introduction, method, results, and discussion.

- Literature reviews synthesize previously published material on a topic. The authors define or clarify the problem, summarize research findings, identify gaps/inconsistencies in the research, and make suggestions for future work. Meta-analyses, in which the authors use quantitative procedures to combine the results of multiple studies, fall into this category.

- Theoretical articles trace the development of a specific theory to expand or refine it, or they present a new theory. Theoretical articles and literature reviews are organized similarly, but empirical information is included in theoretical articles only when it is used to support the theoretical issue.

You may also find methodological articles, case studies, brief reports, and commentary on previously published material. Check with your instructor to determine which articles are appropriate.

Research papers

This assignment involves using published research to provide an overview of and argument about a topic. Simply summarizing the information you read is not enough. Instead, carefully synthesize the information to support your argument. Only discuss the parts of the studies that are relevant to your argument or topic. Headings and subheadings can help guide readers through a long research paper. Our handout on literature reviews may help you organize your research literature.

Choose a topic that is appropriate to the length of the assignment and for which you can find adequate sources. For example, “self-esteem” might be too broad for a 10- page paper, but it may be difficult to find enough articles on “the effects of private school education on female African American children’s self-esteem.” A paper in which you focus on the more general topic of “the effects of school transitions on adolescents’ self-esteem,” however, might work well for the assignment.

Designing your own study/research proposal

You may have the opportunity to design and conduct your own research study or write about the design for one in the form of a research proposal. A good approach is to model your paper on articles you’ve read for class. Here is a general overview of the information that should be included in each section of a research study or proposal:

- Introduction: The introduction conveys a clear understanding of what will be done and why. Present the problem, address its significance, and describe your research strategy. Also discuss the theories that guide the research, previous research that has been conducted, and how your study builds on this literature. Set forth the hypotheses and objectives of the study.

- Methods: This section describes the procedures used to answer your research questions and provides an overview of the analyses that you conducted. For a research proposal, address the procedures that will be used to collect and analyze your data. Do not use the passive voice in this section. For example, it is better to say, “We randomly assigned patients to a treatment group and monitored their progress,” instead of “Patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group and their progress was monitored.” It is acceptable to use “I” or “we,” instead of the third person, when describing your procedures. See the section on reducing bias in language for more tips on writing this section and for discussing the study’s participants.

- Results: This section presents the findings that answer your research questions. Include all data, even if they do not support your hypotheses. If you are presenting statistical results, your instructor will probably expect you to follow the style recommendations of the American Psychological Association. You can also consult our handout on figures and charts . Note that research proposals will not include a results section, but your instructor might expect you to hypothesize about expected results.

- Discussion: Use this section to address the limitations of your study as well as the practical and/or theoretical implications of the results. You should contextualize and support your conclusions by noting how your results compare to the work of others. You can also discuss questions that emerged and call for future research. A research proposal will not include a discussion section. But you can include a short section that addresses the proposed study’s contribution to the literature on the topic.

Other writing assignments

For some assignments, you may be asked to engage personally with the course material. For example, you might provide personal examples to evaluate a theory in a reflection paper. It is appropriate to share personal experiences for this assignment, but be mindful of your audience and provide only relevant and appropriate details.

Writing tips for psychology papers

Psychology is a behavioral science, and writing in psychology is similar to writing in the hard sciences. See our handout on writing in the sciences . The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association provides an extensive discussion on how to write for the discipline. The Manual also gives the rules for psychology’s citation style, called APA. The Library’s citation tutorial will also introduce you to the APA style.

Suggestions for achieving precision and clarity in your writing

- Jargon: Technical vocabulary that is not essential to understanding your ideas can confuse readers. Similarly, refrain from using euphemistic phrases instead of clearer terms. Use “handicapped” instead of “handi-capable,” and “poverty” instead of “monetarily felt scarcity,” for example.

- Anthropomorphism: Anthropomorphism occurs when human characteristics are attributed to animals or inanimate entities. Anthropomorphism can make your writing awkward. Some examples include: “The experiment attempted to demonstrate…,” and “The tables compare…” Reword such sentences so that a person performs the action: “The experimenter attempted to demonstrate…” The verbs “show” or “indicate” can also be used: “The tables show…”

- Verb tenses: Select verb tenses carefully. Use the past tense when expressing actions or conditions that occurred at a specific time in the past, when discussing other people’s work, and when reporting results. Use the present perfect tense to express past actions or conditions that did not occur at a specific time, or to describe an action beginning in the past and continuing in the present.

- Pronoun agreement: Be consistent within and across sentences with pronouns that refer to a noun introduced earlier (antecedent). A common error is a construction such as “Each child responded to questions about their favorite toys.” The sentence should have either a plural subject (children) or a singular pronoun (his or her). Vague pronouns, such as “this” or “that,” without a clear antecedent can confuse readers: “This shows that girls are more likely than boys …” could be rewritten as “These results show that girls are more likely than boys…”

- Avoid figurative language and superlatives: Scientific writing should be as concise and specific as possible. Emotional language and superlatives, such as “very,” “highly,” “astonishingly,” “extremely,” “quite,” and even “exactly,” are imprecise or unnecessary. A line that is “exactly 100 centimeters” is, simply, 100 centimeters.

- Avoid colloquial expressions and informal language: Use “children” rather than “kids;” “many” rather than “a lot;” “acquire” rather than “get;” “prepare for” rather than “get ready;” etc.

Reducing bias in language

Your writing should show respect for research participants and readers, so it is important to choose language that is clear, accurate, and unbiased. The APA sets forth guidelines for reducing bias in language: acknowledge participation, describe individuals at the appropriate level of specificity, and be sensitive to labels. Here are some specific examples of how to reduce bias in your language:

- Acknowledge participation: Use the active voice to acknowledge the subjects’ participation. It is preferable to say, “The students completed the surveys,” instead of “The experimenters administered surveys to the students.” This is especially important when writing about participants in the methods section of a research study.

- Gender: It is inaccurate to use the term “men” when referring to groups composed of multiple genders. See our handout on gender-inclusive language for tips on writing appropriately about gender.

- Race/ethnicity: Be specific, consistent, and sensitive with terms for racial and ethnic groups. If the study participants are Chinese Americans, for instance, don’t refer to them as Asian Americans. Some ethnic designations are outdated or have negative connotations. Use terms that the individuals or groups prefer.

- Clinical terms: Broad clinical terms can be unclear. For example, if you mention “at risk” in your paper, be sure to specify the risk—“at risk for school failure.” The same principle applies to psychological disorders. For instance, “borderline personality disorder” is more precise than “borderline.”

- Labels: Do not equate people with their physical or mental conditions or categorize people broadly as objects. For example, adjectival forms like “older adults” are preferable to labels such as “the elderly” or “the schizophrenics.” Another option is to mention the person first, followed by a descriptive phrase— “people diagnosed with schizophrenia.” Be careful using the label “normal,” as it may imply that others are abnormal.

- Other ways to reduce bias: Consistently presenting information about the socially dominant group first can promote bias. Make sure that you don’t always begin with men followed by other genders when writing about gender, or whites followed by minorities when discussing race and ethnicity. Mention differences only when they are relevant and necessary to understanding the study. For example, it may not be important to indicate the sexual orientation of participants in a study about a drug treatment program’s effectiveness. Sexual orientation may be important to mention, however, when studying bullying among high school students.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. n.d. “Frequently Asked Questions About APA Style®.” APA Style. Accessed June 24, 2019. https://apastyle.apa.org/learn/faqs/index .

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Landrum, Eric. 2008. Undergraduate Writing in Psychology: Learning to Tell the Scientific Story . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Writing a psychology essay can be daunting, because of the constant changes in understanding and differing perspectives that exist in the field. However, if you follow our tips and guidelines you are guaranteed to produce a first-class, high quality psychology essay.

Types of Psychology essay

Psychology essays can come in a range of formats:

- Compare and contrast.

For example:

- Compare the benefits of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with psychoanalysis on patients with schizophrenia.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of family therapy for children of drug addicts.

- CBT is the most effective form of treatment for those struggling with mental illness. Discuss

Once you understand what is being asked of you, and thus the focus of your essay, you can move on to identifying how to structure your work. In all cases the broad structure is similar – an introduction – body section and conclusion. Furthermore, in all cases, your work, and any statements you make should be made using only verifiable, credible sources that should be referenced clearly at the end of your work. To support you in delivering a premium psychology essay, we have indicated a general structure for you to follow.

Introduction

The most important thing about your introduction is it just that. An introduction. It should be short, captivating and hook your reader into wanting to carry on. A good introduction introduces a few key points about the topic so that the reader knows the subject of your paper and its background.

You should also include a thesis statement which describes your intent and perspective on the matter. The statement comes from first identifying a question you wish to ask, for example, “how does CBT differ from psychoanalysis in treating schizophrenics”. This will then enable you to identify a clear statement such as “CBT is more effective in treating schizophrenics than psychoanalysis”. In effect, a captivating introduction sets out what you will be saying in your essay, clearly, concisely, and objectively.

Body of the Essay

The body of the essay is where you make all your relevant points and undertake a dissection of the central themes of your work in the topic area. Note when undertaking a compare and contrast essay it is a good practice to indicate all the similarities and then the differences to ensure a smooth coherent flow.

For each point you make, use a separate paragraph, and ensure that any statements you make are backed up by credible evidence and properly referenced sources. In an evaluation essay, you should indicate the analysis undertaken to make the judgement you have, again backed by credible sources. Discussive psychology essays require you to state your point and then debate it with pros and cons for each side.

Overall, in the body section, you body text should be focused on providing valuable insights and evaluation of the topic and enable you to demonstrate deductive reasoning (“as a result of x… it can be indicated that”) and evidence based analysis (“although x indicates that y, a suggests an alternative view based on…”). Following a logical flow with one point per paragraph ensures the reader is able to follow your thinking process and eventually draw the same conclusions.

Furthermore, it is important when writing a psychology essay to examine a wide range of sources, that cover both sides of a topic or phenomenon. Without demonstrating a wide-ranging knowledge of the diversity of perspectives, you cannot be objective in evaluating a subject area.

In addition, you should recognise that not all your readers may be familiar with psychological terms or acronyms so these need to be explained briefly and concisely the first time they are used. Furthermore, you should avoid definitive statements, because psychology is constantly evolving so do not use phrases such as “this proves…”, instead use terms such as “this is consistent with work by…” or “this supports x’s view that…”. It is also not appropriate to use the first person (“I”), even when expressing opinions, always use the third person and where possible the past tense.

As with the introduction, the conclusion should hold the reader, and crystallise all the arguments and points made into an overall summation of your views. This summation should be in line with your thesis statement which has to be restated here and leave no room for unanswered questions. Your aim is to reaffirm that the points you have made in your body text sum up and provide a clear answer to the task of the psychology essay – whether this compare and contrast, discussion, or evaluation.

Key Phrases for a Psychology Essay

- Previous work in the area has suggested that…

- However, prior studies did not consider…

- In this paper it is therefore argued that…

- The significance of this view is that…

- In light of this indication, there is a potential that…

- In order to understand x, it is necessary to also recognise that…

- Similarly, it has been suggested that…

- Furthermore, additional evidence from x indicates that…

- Conversely, x suggests that…

- Similarly, the indications from … are that…

- That being said, it is also evident that…

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write an Introduction for a Psychology Paper

- Writing Tips

If you are writing a psychology paper, it is essential to kick things off with a strong introduction. The introduction to a psychology research paper helps your readers understand why the topic is important and what they need to know before they delve deeper.

Your goal in this section is to introduce the topic to the reader, provide an overview of previous research on the topic, and identify your own hypothesis .

At a Glance

Writing a great introduction can be a great foundation for the rest of your psychology paper. To create a strong intro:

- Research your topic

- Outline your paper

- Introduce your topic

- Summarize the previous research

- Present your hypothesis or main argument

Before You Write an Introduction

There are some important steps you need to take before you even begin writing your introduction. To know what to write, you need to collect important background information and create a detailed plan.

Research Your Topic

Search a journal database, PsychInfo or ERIC, to find articles on your subject. Once you have located an article, look at the reference section to locate other studies cited in the article. As you take notes from these articles, be sure to write down where you found the information.

A simple note detailing the author's name, journal, and date of publication can help you keep track of sources and avoid plagiarism.

Create a Detailed Outline

This is often one of the most boring and onerous steps, so students tend to skip outlining and go straight to writing. Creating an outline might seem tedious, but it can be an enormous time-saver down the road and will make the writing process much easier.

Start by looking over the notes you made during the research process and consider how you want to present all of your ideas and research.

Introduce the Topic

Once you are ready to write your introduction, your first task is to provide a brief description of the research question. What is the experiment or study attempting to demonstrate? What phenomena are you studying? Provide a brief history of your topic and explain how it relates to your current research.

As you are introducing your topic, consider what makes it important. Why should it matter to your reader? The goal of your introduction is not only to let your reader know what your paper is about, but also to justify why it is important for them to learn more.

If your paper tackles a controversial subject and is focused on resolving the issue, it is important to summarize both sides of the controversy in a fair and impartial way. Consider how your paper fits in with the relevant research on the topic.

The introduction of a research paper is designed to grab interest. It should present a compelling look at the research that already exists and explain to readers what questions your own paper will address.

Summarize Previous Research

The second task of your introduction is to provide a well-rounded summary of previous research that is relevant to your topic. So, before you begin to write this summary, it is important to research your topic thoroughly.

Finding appropriate sources amid thousands of journal articles can be a daunting task, but there are several steps you can take to simplify your research. If you have completed the initial steps of researching and keeping detailed notes, writing your introduction will be much easier.

It is essential to give the reader a good overview of the historical context of the issue you are writing about, but do not feel like you must provide an exhaustive review of the subject. Focus on hitting the main points, and try to include the most relevant studies.

You might describe previous research findings and then explain how the current study differs or expands upon earlier research.

Provide Your Hypothesis

Once you have summarized the previous research, explain areas where the research is lacking or potentially flawed. What is missing from previous studies on your topic? What research questions have yet to be answered? Your hypothesis should lead to these questions.

At the end of your introduction, offer your hypothesis and describe what you expected to find in your experiment or study.

The introduction should be relatively brief. You want to give your readers an overview of a topic, explain why you are addressing it, and provide your arguments.

Tips for Writing Your Psychology Paper Intro

- Use 3x5 inch note cards to write down notes and sources.

- Look in professional psychology journals for examples of introductions.

- Remember to cite your sources.

- Maintain a working bibliography with all of the sources you might use in your final paper. This will make it much easier to prepare your reference section later on.

- Use a copy of the APA style manual to ensure that your introduction and references are in proper APA format .

What This Means For You

Before you delve into the main body of your paper, you need to give your readers some background and present your main argument in the introduction of you paper. You can do this by first explaining what your topic is about, summarizing past research, and then providing your thesis.

Armağan A. How to write an introduction section of a scientific article ? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):8-9. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.046

Fried T, Foltz C, Lendner M, Vaccaro AR. How to write an effective introduction . Clin Spine Surg . 2019;32(3):111-112. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000714

Jawaid SA, Jawaid M. How to write introduction and discussion . Saudi J Anaesth . 2019;13(Suppl 1):S18-S19. doi:10.4103/sja.SJA_584_18

American Psychological Association. Information Recommended for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report New Data Collections Regardless of Research Design . Published 2020.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to Really Write a Psychology Paper

Remember that every research paper is a story..

Posted April 1, 2017 | Reviewed by Matt Huston

I taught my first psychology class in 1994—and I almost always include some kind of paper assignment in each of my classes. Quick math says that I have probably read nearly 2,000 student papers. I think I’m qualified to give advice on this topic.

With a large batch of student papers set to hit my desk on Monday upcoming, it occurred to me that it might be nice to write a formal statement to help guide this process. Here it is.

Tell a Story

If you are writing a research paper, or any paper, you are telling a story. It should have a beginning, middle, and end. Further, it should read how you speak. Some students think that when they are writing for a college professor, they have to up their language and start using all kinds of fancy words and such. Please! We are training you to communicate effectively—not to show others how smart you are. We know you are smart—that is how you got into college in the first place!

While there are certain standards of formality that should be followed in your paper, at the end of the day, always remember that you are primarily trying to communicate some set of ideas to an audience. Thus, you should be keen to attend to the following:

- Create an outline and use it as a roadmap.

- Start from the top. That is, think about your actual question of interest—and start there—clearly and explicitly.

- Make sure that every single sentence points to the next sentence. And every paragraph points to the next paragraph. And every section points to the next section.

- Write how you speak—imagine that you are telling these ideas to someone—and always assume that someone is a layperson (just a regular old person, not an expert in the field).

- Make the paper as long as it needs to be to tell your story fully and effectively—don’t let page limits drive your process (to the extent that this is possible).

- All things equal, note that writing a high number of relatively brief sentences is a better approach than is writing a lower number of relatively long sentences. Often when students write long sentences, the main points get confused.

Use APA Style for Good

Psychology students have to master APA format. This means using the formal writing style of the American Psychological Association . At first, APA style may well seem like a huge pain, but all of the details of APA style actually exist for a reason. This style was designed so that journal editors are able to see a bunch of different papers (manuscripts) that are in the same standardized format. In this context, the editor is then able to make judgments of the differential quality of the different papers based on content and quality. So APA style exists for a reason!

Once you get the basics down, APA style can actually be a tool to help facilitate great writing.

Write a Good Outline and Flesh it Out

For me, the best thing about APA Style is that it gets you to think in terms of an outline. APA style requires you to create headings and subheadings. Every paper I ever write starts with just an outline of APA-inspired headings and subheadings. I make sure that these follow a linear progression—so I can see the big, basic idea at the start—and follow the headings all the way to the end. The headings should be like the Cliff Notes of your story. Someone should be able to read your headings (just like the headings for this post) and get a basic understanding of the story that you are trying to communicate.

Another great thing about starting with an APA-inspired outline is that it affords you a very clear way to compartmentalize your work on the paper. If you are supposed to write a “big” college paper (maybe 20 or so pages), you may dread thinking about it—and you may put it off because you see the task as too daunting.

However, suppose you have an outline with 10 headings and subheadings. Now suppose that you pretty much have about two pages worth of content to say for each such heading. Well you can probably write two pages in about an hour or maybe less. So maybe you flesh out the first heading or two—then watch an episode of The Office or go for a run. Maybe you flesh out another section later in the day. And then tomorrow you wake up and you’ve completed 30% of your paper already. That doesn’t sound so dreadful, now, does it?

No One Wants to Hear Minutia about Other Studies in Your Research Paper!

I’m usually pretty tolerant of the work that my students submit to me. I know that college is all about learning and developing—and I always remind my students that the reason they are in school is to develop skills such as writing—so I don’t expect any 19-year-old to be Walt Whitman.

This said, there are some rookie mistakes that make me shake my head. A very common thing that students tend to do is to describe the research of others in unnecessary detail. For your introduction, you often have to provide evidence to support the points that you raise. So if you are writing a paper about the importance of, say, familial relatedness in affecting altruistic behavior, you probably need to cite some of the classic scientific literature in this area (e.g., Hamilton, 1964).

This said, please, I urge you , don’t describe more about these past studies that you cite than is necessary to tell your story! If your point is that there past work has found that individuals across various species are more likely to help kin than non-kin, maybe just say that! There is a time and a place for describing the details of the studies of others in your own research paper. On occasion, it is actually helpful to elaborate a bit on past studies. But from where I sit, it’s much more common to see students describe others’ studies in painstaking detail in what looks like an attempt to fill up pages.

As a guide on this issue, here are some things that I suggest you NEVER include in your paper:

- The number of participants that were in someone else’s study.

- Information from statistical tests from someone else’s study (e.g., The researchers found a significant F ratio (F(2,199) = 4.32, p = 0.008) ).

- The various conditions or variables that were included in some other study (e.g., These researchers used a mixed-ANOVA model with three between-subject factors and two within-subject factors ).

When you mention the work of others, you are doing so for a purpose. You are citing just enough of their work to substantiate some point that you are making as you work toward creating a coherent story. Don’t ever lose sight of this!

Bottom Line

I’ve read nearly 2,000 student papers to this point in my life. And I hope I am lucky enough to read another 4,000+ before I am pushing up daisies. As I tell my students, if you are going to develop a single skill in college, let it be your ability to write in a clear, effective, and engaging manner.

Students who write psychology papers often find it difficult. That’s OK—that’s expected. If you are a college student, then don’t forget the fact that college is primarily about developing your skills.

Everything you write has the ultimate purpose of communicating to an audience. Clear, straightforward, and narrative approaches to any writing assignment, then, are most likely to hit the mark.

Hamilton W.D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. International Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7 , 1–16.

Glenn Geher, Ph.D. , is professor of psychology at the State University of New York at New Paltz. He is founding director of the campus’ Evolutionary Studies (EvoS) program.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to Write Brilliant Psychology Essays

- Paul Dickerson - University of Roehampton, UK

- Description

“This book is one I wish I had bought at the start of my Psychology degree.” – Five-star review Essay writing is a key part of the Psychology degree and knowing how to write effective and compelling academic essays is key to success. Whether it's understanding how to implement feedback you receive on essays, how to stop procrastinating or what makes an effective introduction, this book covers it all. Drawing on insights derived from teaching thousands of students over a 25-year period How to Write Brilliant Psychology Essays provides the keys that will unlock your writing potential.

Ace your Assignment provide practical tips to help succeed

Exercises help try the theory out in practice

Take away points highlight the key learnings from each chapter

Online resources provide even more help and guidance.

Supplements

Paul Dickerson, Emma McDonald and Christian van Nieuwerburgh discuss study skills, wellbeing and employability and explore how university lecturers and student welfare teams can better support Psychology students through their university journey.

Students enjoyed this text - they found it easy to read and the author's dry sense of humour appealed to many. Not just for psychologists!

A really useful guide for students, breaking down the components of what constitutes a good essay and written from a subject-specific view - highly recommend

I have recommended this to my first year tutorial groups as it provides them with everything they need to know about producing an excellent psychology essay.

Preview this book

For instructors.

Please select a format:

Select a Purchasing Option

Order from:.

- VitalSource

- Amazon Kindle

- Google Play

Related Products

Writing in Psychology

Thursday 2 march 2017, the first class essay, no comments:, post a comment.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing in Psychology Overview

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Psychology is based on the study of human behaviors. As a social science, experimental psychology uses empirical inquiry to help understand human behavior. According to Thrass and Sanford (2000), psychology writing has three elements: describing, explaining, and understanding concepts from a standpoint of empirical investigation.

Discipline-specific writing, such as writing done in psychology, can be similar to other types of writing you have done in the use of the writing process, writing techniques, and in locating and integrating sources. However, the field of psychology also has its own rules and expectations for writing; not everything that you have learned in about writing in the past works for the field of psychology.

Writing in psychology includes the following principles:

- Using plain language : Psychology writing is formal scientific writing that is plain and straightforward. Literary devices such as metaphors, alliteration, or anecdotes are not appropriate for writing in psychology.

- Conciseness and clarity of language : The field of psychology stresses clear, concise prose. You should be able to make connections between empirical evidence, theories, and conclusions. See our OWL handout on conciseness for more information.

- Evidence-based reasoning: Psychology bases its arguments on empirical evidence. Personal examples, narratives, or opinions are not appropriate for psychology.

- Use of APA format: Psychologists use the American Psychological Association (APA) format for publications. While most student writing follows this format, some instructors may provide you with specific formatting requirements that differ from APA format .

Types of writing

Most major writing assignments in psychology courses consists of one of the following two types.

Experimental reports: Experimental reports detail the results of experimental research projects and are most often written in experimental psychology (lab) courses. Experimental reports are write-ups of your results after you have conducted research with participants. This handout provides a description of how to write an experimental report .

Critical analyses or reviews of research : Often called "term papers," a critical analysis of research narrowly examines and draws conclusions from existing literature on a topic of interest. These are frequently written in upper-division survey courses. Our research paper handouts provide a detailed overview of how to write these types of research papers.

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- What Is an Internship? Everything You Should Know

- How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

- How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

- Best Colours for Your PowerPoint Presentation: How to Choose

- How to Write a Nursing Essay

- Top 5 Essential Skills You Should Build As An International Student

- How Professional Editing Services Can Take Your Writing to the Next Level

- How to Write an Effective Essay Outline

- How to Write a Law Essay: A Comprehensive Guide with Examples

- What Are the Limitations of ChatGPT?

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

How to write a first-class essay and ace your degree

(Last updated: 12 May 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

In this article, we’ll take a look at how you can write a first-class essay, giving you the best chance of graduating from university with a first overall.

As this report from 2017 indicates, more people in UK universities are being awarded first-class degrees than ever before. Recent research suggests that by 2030, all students will graduate from some universities with a first-class degree , due to grade inflation.

Inevitably, some are suggesting that this means university standards are falling. Many students now pay vast sums of money for the privilege of a university education. As such, universities want them to leave as "satisfied customers". Perhaps this is why more firsts are being awarded. On the other hand, it could simply be that students have become better at researching what makes for first-class work. They're better at examining marking briefs. And at sharing tips – with other students in online forums and elsewhere – about what a first looks like.

So what does this mean for you if you're currently an undergraduate student? If you think this recent news means it's more likely you'll get a first, you can keep the Champagne on ice for now. A first-class degree takes hard work and dedication, no matter where or what you study.

Whatever the reasons for the recent spike in firsts, you can be sure that as a result, the following will now happen:

- Universities will examine their standards more closely. They may look at making the criteria for first-class degrees more stringent in response to criticisms that they've 'gone soft'.

- As up to a quarter of the new graduates hitting the job market do so with a shiny new first-class degree, top employers will routinely come to expect this in applicants for their very best jobs.

How can I get a first in my degree?

So, you want to be among those brandishing a first-class degree certificate when you don cap and gown next summer? Of course you do. Now is the time to think about what kind of student you need to be in order to succeed.

Here are a few pointers:

It doesn't take a genius to work out that the more first-class essays you write at university, the more likely you are to score highly overall. And getting a First in your essay isn't as hard as you think. More on this later.

A marker doesn't need to get very far into your work to see if it's been written by somebody who has engaged with the subject matter in depth, and taken the time to understand its nuances. Or if the person who wrote it had only a basic grasp of the main concepts.

All the knowledge in the world won't score you a first if you don't also have the rhetorical skills to express that knowledge fluently and succinctly. You need dexterity to marshal your knowledge effectively and solve the problem at hand (whether that's a long-form essay topic or an exam question).

Knowing your topic inside-out, but finding yourself unable to convey all that detailed knowledge, is immensely frustrating. If feedback on your previous work suggests your writing may not be up to scratch, be sure to take advantage of the help that's on offer at your university. This can be online tutorials, student mentors, or writing workshops. Nearly all universities offer academic writing support services to students, and these are often run by the library.

Alternatively, delve into the Oxbridge Essays blog for posts containing great general advice on good essay writing and essay writing tips .

Finally, the Essay Writing Service from Oxbridge Essays is a reliable place to turn to for essay help. Our academics can help tweak your writing, or write a completely original, unplagiarised essay for you to use as inspiration in your own writing.

Just reading the assigned work and writing solid assignments will, at best, get you a 2:1. In fact, that's what Second-class degree classifications were designed for! If you want to stand out from the crowd, you need to be prepared to go the extra mile. Find ways of understanding your subject matter more thoroughly. Craft an "angle" from which you can approach the topic in a memorable, original, and unique way.

You need to be willing to take risks, and be willing to put that safe, 2:1-level assignment you were going to write on the line in pursuit of greater reward. More on what this means below, but essentially you should be willing to take up positions that are controversial, sceptical and critical – and back them up.

You should even be willing, once in a while, to fail to reach the lofty aspirations you've set yourself. If you've ever watched a professional poker player you'll know that even the best of them don't win every hand. What's important is that they're ahead when they leave the table.

What does a first-class essay look like?

A lot of this stuff – risk-taking, depth of knowledge, and developing a unique "angle" – can sound pretty abstract. People marking essays may land on opposite sides of the fence where borderline cases are concerned.

However, most agree with what a first-class essay looks like and can pinpoint features that set it apart. Markers look for things like:

Essay matches the assignment brief

This may sound obvious, but did you really read the assignment brief? And when did you last read it? A first-class essay needs to show originality and creativity. But it also needs to prove that you can follow instructions.

If you've been given guidance on what your essay needs to cover, make sure you follow this to the letter. Also, take note of the number and type of sources it needs to use, or any other instructions. You can only do this if you revisit the brief repeatedly while writing. This will ensure you're still on the path you were originally pointed down and haven't gone off at a tangent.

Writing a brilliant, original essay that doesn't meet the assignment brief is likely to be a frustrating waste of effort. True, you may well still get sufficient credit for your originality. But you'll achieve far more marks if you shoot for originality and accuracy.

A clear and sophisticated argument

A first-class essay sets out its intentions (its own criteria for success) explicitly. By the end of your first couple of paragraphs, your reader should know (a) what you are hoping to accomplish, and (b) how you plan on accomplishing it.

Your central argument – or thesis – shapes everything else about your essay. So you need to make sure it's well-thought-out. For a first-class essay, this argument shouldn't just rehash the module material. It shouldn't regurgitate one of the positions you've learned about in class. It should build on one or more of these positions by interrogating them, bringing them into conflict or otherwise disrupting them.

Solid support for every argument

You don't just need to make a sophisticated argument; you need to support it as well. Use primary and/or secondary sources to back up everything you say. Be particularly careful to back up anything contentious with rigorous, logically consistent argumentation.

Undergraduates also often forget the need to effectively address counter-arguments to their own position. If there are alternative positions to the one you're taking (and there almost always are), don't omit these from your essay. Address them head-on by quoting their authors (if they're established positions). Or, simply hypothesise alternative interpretations to your own. Explain why your position is more persuasive, logical, or better-supported than the alternatives.

When done well, drawing attention to counter-arguments doesn't detract from your own argument. It enhances it by providing evidence of your capacity to reason in a careful, meticulous, sceptical and balanced way.

A logical and appropriate structure

Have you ever been asked to write a comparative essay, say on a couple of literary texts? And did you have lots to say about one of the texts but not much at all about the other? How did you approach that challenge? We've all written the "brain-dump" essay. You shape your work not around the question you're supposed to be answering, but around topic areas that you can comfortably write a lot about. Your approach to a comparative essay may be to write 2500 words about the text you love, and tack 500 words onto the end about the one you don't care for. If so, your mindset needs a bit of adjusting if you're going to get that first-class degree.

A first-class essay always presents its arguments and its supporting evidence in the order and manner that's best suited to its overall goals. Not according to what topic areas its author finds the most interesting or most comfortable to talk about. It can chafe if you feel you have more to offer on a particular topic than the assignment allows you to include. But balance and structural discipline are essential components of any good essay.

In-depth engagement and intellectual risk

This is where going "above and beyond" comes in. Everything from your thesis statement to your bibliography can and will be weighed as evidence of the depth of your engagement with the topic. If you've set yourself the challenge of defending a fringe position on a topic, or have delved deep into the theories underlying the positions of your set texts, you've clearly set yourself up for a potential first in the essay. None of this is enough by itself, though. Don't forget that you need to execute it in a disciplined and organised fashion!

Emerging understanding of your role in knowledge creation

This one is easy to overlook, but even as a university student you're part of a system that collaboratively creates knowledge. You can contribute meaningfully to this system by provoking your tutors to see problems or areas in their field differently. This may influence the way they teach (or research, or write about) this material in future. Top students demonstrate that they're aware of this role in collaborative knowledge creation. It is clear they take it seriously, in the work they submit.

The best way to communicate this is to pay attention to two things. First, the content of the quality sources you read in the course of your studies. Second, the rhetorical style these sources employ. Learn the language, and frame your arguments in the same way scholars do. For example, "What I want to suggest by juxtaposing these two theories is…" or, "The purpose of this intervention is…" and so on.

In short, you need to present an essay that shows the following:

Clarity of purpose, integrity of structure, originality of argument, and confidence of delivery.

What else can I do to get a first in my essays?

It will take time to perfect an essay-writing strategy that delivers all this while persuading your reader that your paper is evidence of real intellectual risk. And that it goes above and beyond what's expected of the typical undergraduate at your level. But here are a few tips to help give you the best possible chance:

Start early

Your module may have a long reading list that will be tricky to keep on top of during the term. If so, make sure you get the list (and, if possible, the syllabus showing what kind of essays the module will require) ahead of time. If your module starts in September, spend some time over summer doing preparatory reading . Also, think about which areas of the module pique your interest.

Once the module starts, remember: it's never too early in the term to start thinking about the essays that are due at the end of it. Don't wait until the essay topics circulate a few weeks before term-end. Think now about the topics that especially interest you. Then read around to get a better understanding of their histories and the current debates.

Read beyond the syllabus

Students who are heading for a good 2:1 degree tend to see the module reading list as the start and end of their workload. They don't necessary see beyond it. A 2:1 student considers it a job well done if they've done "all the reading". However, a student capable of a first knows there's no such thing as "all the reading". Every scholarly text on your syllabus, whether it's required or suggested reading, is a jumping-off point . It's a place to begin to look for the origins and intellectual histories of the topics you're engaged with. It will often lead you to more challenging material than what's on the syllabus.

Search through the bibliographies of the texts on the syllabus to discover the texts they draw from, and then go look them up. At undergraduate level, set texts are often simplified versions of complex scholarly works and notions. They're designed to distil intricate ideas down into more manageable overview material. But wrestling with complex articles is the best way to demonstrate that you're engaging with the topic in depth, with a sophisticated level of understanding.

Build your bibliography as you research

Keeping notes of all your sources used in research will make writing your bibliography later far less of a chore. Given that every single text on your syllabus likely references thirty more, bibliography mining can quickly become overwhelming. Luckily, we have to hand the integration of web searches and referencing tools. These integrations make the challenge of compiling and sifting through references far easier than it once was. Get into the habit of exporting every reference you search for into the bibliographic software program of your choice.

Your institution might have a subscription to a a commercial tool such as RefWorks or Endnote. But the freeware tool Zotero is more than capable of compiling references and allowing you to add notes to revisit later. It's usually a matter of adding a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for your source into the program. Then it will store all the details you need to generate a bibliography for your essay later (no matter what reference style your university demands). It will also store the URL of the source so you can retrieve it later.

Make sure you organise your research into categories. This will ensure you have a focused set of scholarly sources waiting for you when you've decided on your final essay topic.

Develop your own essay topic, and talk to your tutor (often!)

Are you the kind of student who likes to go it alone, and rarely, if ever, visits your tutor during his or her office hours? If you're serious about getting a first, you need to get over any reservations you have about seeing your tutor often. Make regular appointments to talk through your essay ideas. If the syllabus allows it, come up with your own essay topic rather than going with any in the topic list you're given.

Even if you haven't explicitly been told that you can design your own essay topic, ask if it's possible. Nothing is a clearer mark of your originality and active engagement with the module content than defining exactly what it is you want to write about, and how you intend to approach the argument. You have nothing to lose and everything to gain by expressing enthusiasm for the material, and a desire to think independently about it. And one of your tutor's roles is to help you develop your arguments. S/he might suggest texts you haven't come across yet that will help support your points, or make your arguments stronger by challenging them.

Don't just synthesise; critique and contest

It's common for students to get frustrated when they do all of the above and still come away with a good 2:1, rather than the first they were expecting. For some, this can happen because reading very widely can 'muddy' the waters of their understanding. Reading more about a subject will help you understand its depth and complexity. But it can cause you to begin to lose rather than gain confidence in your own understanding.

It can be tempting to let your essays become summaries of what other scholars have said, and let their voices speak over your own. This is especially true when you've read widely and have a sound understanding of the positions of scholars in your field.

But it doesn't matter how much reading you've done or how sound your knowledge of existing work in a field. To consistently score first-class marks, you have to develop a position on that field. You must examine where you stand in relation to these scholars and ask yourself some fundamental questions:

1. Do I agree with them? 2. If not, why not? 3. How can I articulate and defend my position?

If you've thought long and hard about these questions in every module you take, your journey to a first-class degree is well underway. There is, admittedly, a degree of risk here. What if you've fundamentally misunderstood some key aspect of a debate? What if your position simply doesn't add up?

There will be times when you'll get things wrong, and you'll feel frustrated or even embarrassed. But that's why we said at the outset that you need to be a gambler – this approach will pay off far more often than it will fail. And if you're feeling particularly insecure about a line of reasoning, ask your tutor to read over a draft and give you some pointers on where to go next.

Is it worth the risk?

In a word, yes. Not every attempt at academic risk-taking will be entirely successful. But following the steps above will ensure that tutors and markers see genuine, in-depth engagement with the topic. Not to mention evidence of serious intellectual growth.

Markers will take all this into account, as well as pointing out the places where your argument didn't quite hit the mark. So even if the risk doesn't quite work out, you're unlikely to get a lower mark than playing it safe and submitting a “solid 2:1” piece. And over the span of your degree, this approach will yield a higher mark than consistently writing competent essays on the set texts without significant innovation or risk.

Plus, of course, this process has its own rewards beyond your essay mark. Even if you didn't quite hit your target score for this module, your engagement with the topic will have been far richer. You'll emerge far more knowledgeable at the end of it than if you'd played it safe.

So go ahead… live a little!

A freshers’ guide to money and work

Everything you need to know about exam resits

Top 10 tips for writing a dissertation methodology

- academic writing

- essay writing

- study skills

- writing a good essay

- writing tips

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Approximate reading time: 6 minutes

Asking the Right Questions: Why? What? and How?

In psychology, the questions “Why?”, “What?”, and “How?” are foundational. They guide us to explore behaviours, observe details, and understand processes. This questioning approach is essential for uncovering insights into human nature and behaviour.

The Importance of “Why?”

At the heart of psychology lies a simple yet profound question: “Why?” This isn’t just about curiosity; it’s the cornerstone of psychological inquiry that we use to understand human nature.

As you begin your study of psychology, you’ll discover that “Why?” is more than a question. It’s a deliberate and strategic approach to thinking — an inquiring mindset. It represents a practice of curiosity, a keen interest in the world, and an acknowledgment of our right, perhaps even responsibility, to ask “why.” This inquiring mindset is crucial for anyone aspiring to be a psychology professional; it drives us to look beyond the surface and uncover deeper meanings and motivations behind human actions and thoughts.

But “Why?” doesn’t stand alone. It’s complemented by two equally important questions: “What?” and “How?”

“What?”: The Art of Observation

The question “What?” calls for our careful, detailed, and unbiased observation. It requires us to gather facts and see the world as it is, not as we assume it to be. In psychology, this means observing behaviour, emotions, thoughts, and interactions with an open mind. This textbook will guide you in building observational skills, teaching you to notice the subtleties and complexities of human behaviour. Without a clear understanding of “what” is happening, we cannot hope to answer “why” it happens. For example, “What happens physically, emotionally and mentally just before someone breaks out into a nervous laugh?” must come before we can answer, “Why do some people laugh when they are nervous?”

“How?”: Understanding Mechanisms

The question, “How?” demands our exploration of the processes and mechanisms that explain all the phenomena that we can observe. It compels us to delve into the underlying workings and understand the precursors (i.e., what must be present before anything can happen), the step-by-step sequence of events, and the cause and effect — not just as it appears on the surface but at every level. In psychology, answering “how” often requires expert training and sometimes the use of specialised technology to reveal the processes of the human mind and body. This textbook will introduce you to some of the methods and tools psychology professionals use to understand how thoughts, feelings and behaviours are learned, processed, and expressed. From following a long chain of neural pathways to mapping family dynamics and social influences, you’ll learn how it is that many variables and contexts come to shape us.

Learning Activity: Flex your Question-Storming Muscles

Here are some questions to get you started asking your own “why, what, and how” questions and growing your question-storming “muscles.” First, read these sample questions. Then set your timer for two minutes and write down as many psychology-related questions (that you do not currently know the answer to) as you can think of in that time. Don’t censor yourself. Don’t let your fingers pause. Just go. Reset your timer and repeat three times: once for “Why?” once for “What?” and once for “How?” Share your questions with someone. What questions did you like the best? What questions made you laugh? What questions did you most want to know the answers to?

- Why can’t we tickle ourselves?

- Why do we yawn when we see someone else yawning?

- Why do we enjoy watching scary movies?

- Why do some people have a fear of clowns?

- Why do we find it hard to resist kittens and puppies?

… Your turn. You have 2 minutes. Go!

- What causes us to laugh?

- What causes us to have a “favourite colour”?

- What goes on in our minds when we are daydreaming?