Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 21, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023.

The discussion section is where you delve into the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results .

It should focus on explaining and evaluating what you found, showing how it relates to your literature review and paper or dissertation topic , and making an argument in support of your overall conclusion. It should not be a second results section.

There are different ways to write this section, but you can focus your writing around these key elements:

- Summary : A brief recap of your key results

- Interpretations: What do your results mean?

- Implications: Why do your results matter?

- Limitations: What can’t your results tell us?

- Recommendations: Avenues for further studies or analyses

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What not to include in your discussion section, step 1: summarize your key findings, step 2: give your interpretations, step 3: discuss the implications, step 4: acknowledge the limitations, step 5: share your recommendations, discussion section example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about discussion sections.

There are a few common mistakes to avoid when writing the discussion section of your paper.

- Don’t introduce new results: You should only discuss the data that you have already reported in your results section .

- Don’t make inflated claims: Avoid overinterpretation and speculation that isn’t directly supported by your data.

- Don’t undermine your research: The discussion of limitations should aim to strengthen your credibility, not emphasize weaknesses or failures.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Start this section by reiterating your research problem and concisely summarizing your major findings. To speed up the process you can use a summarizer to quickly get an overview of all important findings. Don’t just repeat all the data you have already reported—aim for a clear statement of the overall result that directly answers your main research question . This should be no more than one paragraph.

Many students struggle with the differences between a discussion section and a results section . The crux of the matter is that your results sections should present your results, and your discussion section should subjectively evaluate them. Try not to blend elements of these two sections, in order to keep your paper sharp.

- The results indicate that…

- The study demonstrates a correlation between…

- This analysis supports the theory that…

- The data suggest that…

The meaning of your results may seem obvious to you, but it’s important to spell out their significance for your reader, showing exactly how they answer your research question.

The form of your interpretations will depend on the type of research, but some typical approaches to interpreting the data include:

- Identifying correlations , patterns, and relationships among the data

- Discussing whether the results met your expectations or supported your hypotheses

- Contextualizing your findings within previous research and theory

- Explaining unexpected results and evaluating their significance

- Considering possible alternative explanations and making an argument for your position

You can organize your discussion around key themes, hypotheses, or research questions, following the same structure as your results section. Alternatively, you can also begin by highlighting the most significant or unexpected results.

- In line with the hypothesis…

- Contrary to the hypothesized association…

- The results contradict the claims of Smith (2022) that…

- The results might suggest that x . However, based on the findings of similar studies, a more plausible explanation is y .

As well as giving your own interpretations, make sure to relate your results back to the scholarly work that you surveyed in the literature review . The discussion should show how your findings fit with existing knowledge, what new insights they contribute, and what consequences they have for theory or practice.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support existing theories, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge existing theories, why do you think that is?

- Are there any practical implications?

Your overall aim is to show the reader exactly what your research has contributed, and why they should care.

- These results build on existing evidence of…

- The results do not fit with the theory that…

- The experiment provides a new insight into the relationship between…

- These results should be taken into account when considering how to…

- The data contribute a clearer understanding of…

- While previous research has focused on x , these results demonstrate that y .

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Even the best research has its limitations. Acknowledging these is important to demonstrate your credibility. Limitations aren’t about listing your errors, but about providing an accurate picture of what can and cannot be concluded from your study.

Limitations might be due to your overall research design, specific methodological choices , or unanticipated obstacles that emerged during your research process.

Here are a few common possibilities:

- If your sample size was small or limited to a specific group of people, explain how generalizability is limited.

- If you encountered problems when gathering or analyzing data, explain how these influenced the results.

- If there are potential confounding variables that you were unable to control, acknowledge the effect these may have had.

After noting the limitations, you can reiterate why the results are nonetheless valid for the purpose of answering your research question.

- The generalizability of the results is limited by…

- The reliability of these data is impacted by…

- Due to the lack of data on x , the results cannot confirm…

- The methodological choices were constrained by…

- It is beyond the scope of this study to…

Based on the discussion of your results, you can make recommendations for practical implementation or further research. Sometimes, the recommendations are saved for the conclusion .

Suggestions for further research can lead directly from the limitations. Don’t just state that more studies should be done—give concrete ideas for how future work can build on areas that your own research was unable to address.

- Further research is needed to establish…

- Future studies should take into account…

- Avenues for future research include…

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

In the discussion , you explore the meaning and relevance of your research results , explaining how they fit with existing research and theory. Discuss:

- Your interpretations : what do the results tell us?

- The implications : why do the results matter?

- The limitation s : what can’t the results tell us?

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/discussion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a results section | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Guide to Writing the Results and Discussion Sections of a Scientific Article

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing ( Bordage, 2001 ). In addition, a research paper must be clear, concise, and effective when presenting the information in an organized structure with a logical manner ( Sandercock, 2013 ).

In this article, we will take a closer look at the results and discussion section. Composing each of these carefully with sufficient data and well-constructed arguments can help improve your paper overall.

The results section of your research paper contains a description about the main findings of your research, whereas the discussion section interprets the results for readers and provides the significance of the findings. The discussion should not repeat the results.

Let’s dive in a little deeper about how to properly, and clearly organize each part.

How to Organize the Results Section

Since your results follow your methods, you’ll want to provide information about what you discovered from the methods you used, such as your research data. In other words, what were the outcomes of the methods you used?

You may also include information about the measurement of your data, variables, treatments, and statistical analyses.

To start, organize your research data based on how important those are in relation to your research questions. This section should focus on showing major results that support or reject your research hypothesis. Include your least important data as supplemental materials when submitting to the journal.

The next step is to prioritize your research data based on importance – focusing heavily on the information that directly relates to your research questions using the subheadings.

The organization of the subheadings for the results section usually mirrors the methods section. It should follow a logical and chronological order.

Subheading organization

Subheadings within your results section are primarily going to detail major findings within each important experiment. And the first paragraph of your results section should be dedicated to your main findings (findings that answer your overall research question and lead to your conclusion) (Hofmann, 2013).

In the book “Writing in the Biological Sciences,” author Angelika Hofmann recommends you structure your results subsection paragraphs as follows:

- Experimental purpose

- Interpretation

Each subheading may contain a combination of ( Bahadoran, 2019 ; Hofmann, 2013, pg. 62-63):

- Text: to explain about the research data

- Figures: to display the research data and to show trends or relationships, for examples using graphs or gel pictures.

- Tables: to represent a large data and exact value

Decide on the best way to present your data — in the form of text, figures or tables (Hofmann, 2013).

Data or Results?

Sometimes we get confused about how to differentiate between data and results . Data are information (facts or numbers) that you collected from your research ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

Whereas, results are the texts presenting the meaning of your research data ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

One mistake that some authors often make is to use text to direct the reader to find a specific table or figure without further explanation. This can confuse readers when they interpret data completely different from what the authors had in mind. So, you should briefly explain your data to make your information clear for the readers.

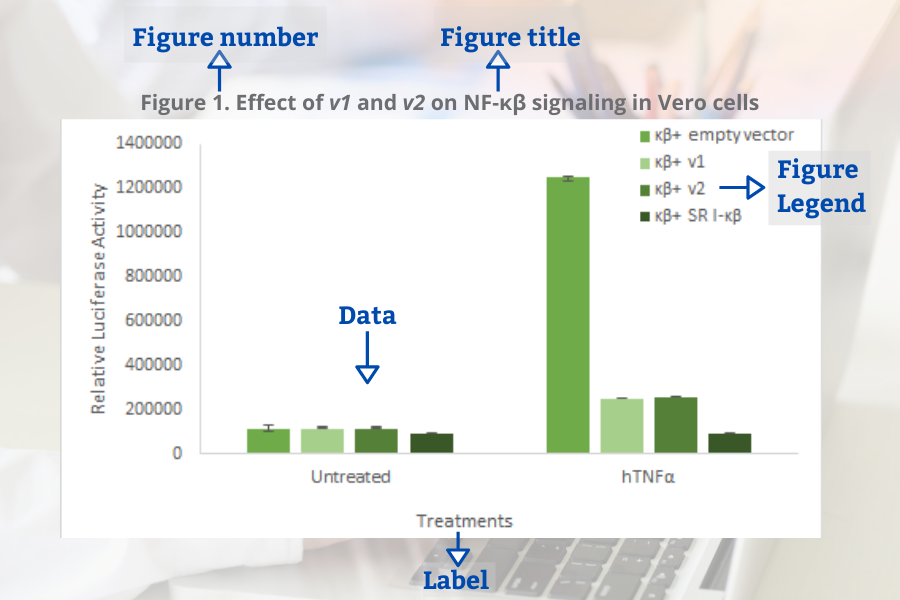

Common Elements in Figures and Tables

Figures and tables present information about your research data visually. The use of these visual elements is necessary so readers can summarize, compare, and interpret large data at a glance. You can use graphs or figures to compare groups or patterns. Whereas, tables are ideal to present large quantities of data and exact values.

Several components are needed to create your figures and tables. These elements are important to sort your data based on groups (or treatments). It will be easier for the readers to see the similarities and differences among the groups.

When presenting your research data in the form of figures and tables, organize your data based on the steps of the research leading you into a conclusion.

Common elements of the figures (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Figure number

- Figure title

- Figure legend (for example a brief title, experimental/statistical information, or definition of symbols).

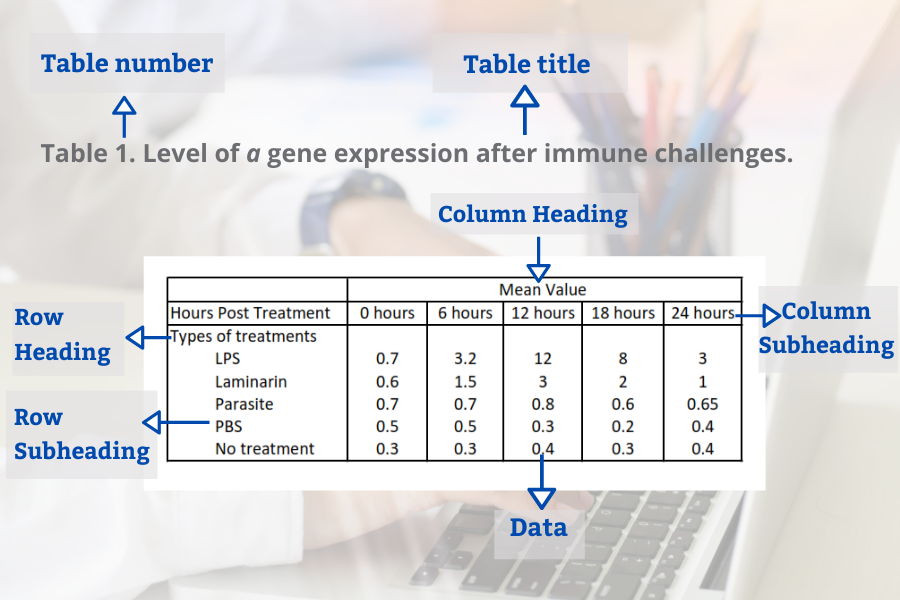

Tables in the result section may contain several elements (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Table number

- Table title

- Row headings (for example groups)

- Column headings

- Row subheadings (for example categories or groups)

- Column subheadings (for example categories or variables)

- Footnotes (for example statistical analyses)

Tips to Write the Results Section

- Direct the reader to the research data and explain the meaning of the data.

- Avoid using a repetitive sentence structure to explain a new set of data.

- Write and highlight important findings in your results.

- Use the same order as the subheadings of the methods section.

- Match the results with the research questions from the introduction. Your results should answer your research questions.

- Be sure to mention the figures and tables in the body of your text.

- Make sure there is no mismatch between the table number or the figure number in text and in figure/tables.

- Only present data that support the significance of your study. You can provide additional data in tables and figures as supplementary material.

How to Organize the Discussion Section

It’s not enough to use figures and tables in your results section to convince your readers about the importance of your findings. You need to support your results section by providing more explanation in the discussion section about what you found.

In the discussion section, based on your findings, you defend the answers to your research questions and create arguments to support your conclusions.

Below is a list of questions to guide you when organizing the structure of your discussion section ( Viera et al ., 2018 ):

- What experiments did you conduct and what were the results?

- What do the results mean?

- What were the important results from your study?

- How did the results answer your research questions?

- Did your results support your hypothesis or reject your hypothesis?

- What are the variables or factors that might affect your results?

- What were the strengths and limitations of your study?

- What other published works support your findings?

- What other published works contradict your findings?

- What possible factors might cause your findings different from other findings?

- What is the significance of your research?

- What are new research questions to explore based on your findings?

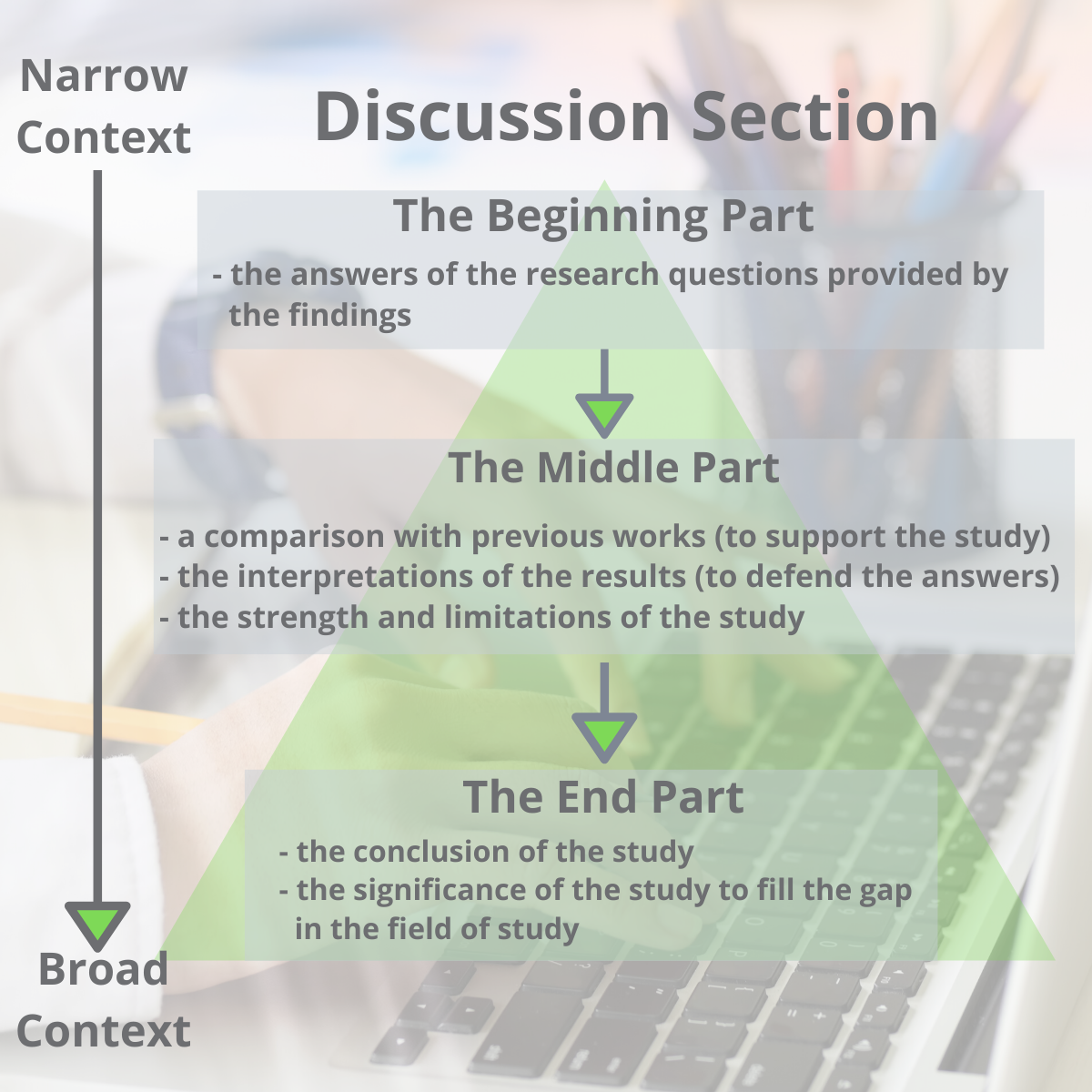

Organizing the Discussion Section

The structure of the discussion section may be different from one paper to another, but it commonly has a beginning, middle-, and end- to the section.

One way to organize the structure of the discussion section is by dividing it into three parts (Ghasemi, 2019):

- The beginning: The first sentence of the first paragraph should state the importance and the new findings of your research. The first paragraph may also include answers to your research questions mentioned in your introduction section.

- The middle: The middle should contain the interpretations of the results to defend your answers, the strength of the study, the limitations of the study, and an update literature review that validates your findings.

- The end: The end concludes the study and the significance of your research.

Another possible way to organize the discussion section was proposed by Michael Docherty in British Medical Journal: is by using this structure ( Docherty, 1999 ):

- Discussion of important findings

- Comparison of your results with other published works

- Include the strengths and limitations of the study

- Conclusion and possible implications of your study, including the significance of your study – address why and how is it meaningful

- Future research questions based on your findings

Finally, a last option is structuring your discussion this way (Hofmann, 2013, pg. 104):

- First Paragraph: Provide an interpretation based on your key findings. Then support your interpretation with evidence.

- Secondary results

- Limitations

- Unexpected findings

- Comparisons to previous publications

- Last Paragraph: The last paragraph should provide a summarization (conclusion) along with detailing the significance, implications and potential next steps.

Remember, at the heart of the discussion section is presenting an interpretation of your major findings.

Tips to Write the Discussion Section

- Highlight the significance of your findings

- Mention how the study will fill a gap in knowledge.

- Indicate the implication of your research.

- Avoid generalizing, misinterpreting your results, drawing a conclusion with no supportive findings from your results.

Aggarwal, R., & Sahni, P. (2018). The Results Section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 21-38): Springer.

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A., Hosseinpanah, F., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The principles of biomedical scientific writing: Results. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(2).

Bordage, G. (2001). Reasons reviewers reject and accept manuscripts: the strengths and weaknesses in medical education reports. Academic medicine, 76(9), 889-896.

Cals, J. W., & Kotz, D. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VI: discussion. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(10), 1064.

Docherty, M., & Smith, R. (1999). The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers: Much the same as that for structuring abstracts. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Faber, J. (2017). Writing scientific manuscripts: most common mistakes. Dental press journal of orthodontics, 22(5), 113-117.

Fletcher, R. H., & Fletcher, S. W. (2018). The discussion section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 39-48): Springer.

Ghasemi, A., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Hosseinpanah, F., Shiva, N., & Zadeh-Vakili, A. (2019). The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Discussion. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(3).

Hofmann, A. H. (2013). Writing in the biological sciences: a comprehensive resource for scientific communication . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kotz, D., & Cals, J. W. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part V: results. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(9), 945.

Mack, C. (2014). How to Write a Good Scientific Paper: Structure and Organization. Journal of Micro/ Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS, 13. doi:10.1117/1.JMM.13.4.040101

Moore, A. (2016). What's in a Discussion section? Exploiting 2‐dimensionality in the online world…. Bioessays, 38(12), 1185-1185.

Peat, J., Elliott, E., Baur, L., & Keena, V. (2013). Scientific writing: easy when you know how: John Wiley & Sons.

Sandercock, P. M. L. (2012). How to write and publish a scientific article. Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, 45(1), 1-5.

Teo, E. K. (2016). Effective Medical Writing: The Write Way to Get Published. Singapore Medical Journal, 57(9), 523-523. doi:10.11622/smedj.2016156

Van Way III, C. W. (2007). Writing a scientific paper. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 22(6), 636-640.

Vieira, R. F., Lima, R. C. d., & Mizubuti, E. S. G. (2019). How to write the discussion section of a scientific article. Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy, 41.

Related Articles

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing (Bordage, 200...

How to Survive and Complete a Thesis or a Dissertation

Writing a thesis or a dissertation can be a challenging process for many graduate students. There ar...

12 Ways to Dramatically Improve your Research Manuscript Title and Abstract

The first thing a person doing literary research will see is a research publication title. After tha...

15 Laboratory Notebook Tips to Help with your Research Manuscript

Your lab notebook is a foundation to your research manuscript. It serves almost as a rudimentary dra...

Join our list to receive promos and articles.

- Competent Cells

- Lab Startup

- Z')" data-type="collection" title="Products A->Z" target="_self" href="/collection/products-a-to-z">Products A->Z

- GoldBio Resources

- GoldBio Sales Team

- GoldBio Distributors

- Duchefa Direct

- Sign up for Promos

- Terms & Conditions

- ISO Certification

- Agarose Resins

- Antibiotics & Selection

- Biochemical Reagents

- Bioluminescence

- Buffers & Reagents

- Cell Culture

- Cloning & Induction

- Competent Cells and Transformation

- Detergents & Membrane Agents

- DNA Amplification

- Enzymes, Inhibitors & Substrates

- Growth Factors and Cytokines

- Lab Tools & Accessories

- Plant Research and Reagents

- Protein Research & Analysis

- Protein Expression & Purification

- Reducing Agents

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write a discussion section?

Writing manuscripts to describe study outcomes, although not easy, is the main task of an academician. The aim of the present review is to outline the main aspects of writing the discussion section of a manuscript. Additionally, we address various issues regarding manuscripts in general. It is advisable to work on a manuscript regularly to avoid losing familiarity with the article. On principle, simple, clear and effective language should be used throughout the text. In addition, a pre-peer review process is recommended to obtain feedback on the manuscript. The discussion section can be written in 3 parts: an introductory paragraph, intermediate paragraphs and a conclusion paragraph. For intermediate paragraphs, a “divide and conquer” approach, meaning a full paragraph describing each of the study endpoints, can be used. In conclusion, academic writing is similar to other skills, and practice makes perfect.

Introduction

Sharing knowledge produced during academic life is achieved through writing manuscripts. However writing manuscripts is a challenging endeavour in that we physicians have a heavy workload, and English which is common language used for the dissemination of scientific knowledge is not our mother tongue.

The objective of this review is to summarize the method of writing ‘Discussion’ section which is the most important, but probably at the same time the most unlikable part of a manuscript, and demonstrate the easy ways we applied in our practice, and finally share the frequently made relevant mistakes. During this procedure, inevitably some issues which concerns general concept of manuscript writing process are dealt with. Therefore in this review we will deal with topics related to the general aspects of manuscript writing process, and specifically issues concerning only the ‘Discussion’ section.

A) Approaches to general aspects of manuscript writing process:

1. what should be the strategy of sparing time for manuscript writing be.

Two different approaches can be formulated on this issue? One of them is to allocate at least 30 minutes a day for writing a manuscript which amounts to 3.5 hours a week. This period of time is adequate for completion of a manuscript within a few weeks which can be generally considered as a long time interval. Fundamental advantage of this approach is to gain a habit of making academic researches if one complies with the designated time schedule, and to keep the manuscript writing motivation at persistently high levels. Another approach concerning this issue is to accomplish manuscript writing process within a week. With the latter approach, the target is rapidly attained. However longer time periods spent in order to concentrate on the subject matter can be boring, and lead to loss of motivation. Daily working requirements unrelated to the manuscript writing might intervene, and prolong manuscript writing process. Alienation periods can cause loss of time because of need for recurrent literature reviews. The most optimal approach to manuscript writing process is daily writing strategy where higher levels of motivation are persistently maintained.

Especially before writing the manuscript, the most important step at the start is to construct a draft, and completion of the manuscript on a theoretical basis. Therefore, during construction of a draft, attention distracting environment should be avoided, and this step should be completed within 1–2 hours. On the other hand, manuscript writing process should begin before the completion of the study (even the during project stage). The justification of this approach is to see the missing aspects of the study and the manuscript writing methodology, and try to solve the relevant problems before completion of the study. Generally, after completion of the study, it is very difficult to solve the problems which might be discerned during the writing process. Herein, at least drafts of the ‘Introduction’, and ‘Material and Methods’ can be written, and even tables containing numerical data can be constructed. These tables can be written down in the ‘Results’ section. [ 1 ]

2. How should the manuscript be written?

The most important principle to be remembered on this issue is to obey the criteria of simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness. [ 2 ] Herein, do not forget that, the objective should be to share our findings with the readers in an easily comprehensible format. Our approach on this subject is to write all structured parts of the manuscript at the same time, and start writing the manuscript while reading the first literature. Thus newly arisen connotations, and self-brain gyms will be promptly written down. However during this process your outcomes should be revealed fully, and roughly the message of the manuscript which be delivered. Thus with this so-called ‘hunter’s approach’ the target can be achieved directly, and rapidly. Another approach is ‘collectioner’s approach. [ 3 ] In this approach, firstly, potential data, and literature studies are gathered, read, and then selected ones are used. Since this approach suits with surgical point of view, probably ‘hunter’s approach’ serves our purposes more appropriately. However, in parallel with academic development, our novice colleague ‘manuscripters’ can prefer ‘collectioner’s approach.’

On the other hand, we think that research team consisting of different age groups has some advantages. Indeed young colleagues have the enthusiasm, and energy required for the conduction of the study, while middle-aged researchers have the knowledge to manage the research, and manuscript writing. Experienced researchers make guiding contributions to the manuscript. However working together in harmony requires assignment of a chief researcher, and periodically organizing advancement meetings. Besides, talents, skills, and experiences of the researchers in different fields (ie. research methods, contact with patients, preparation of a project, fund-raising, statistical analysis etc.) will determine task sharing, and make a favourable contribution to the perfection of the manuscript. Achievement of the shared duties within a predetermined time frame will sustain the motivation of the researchers, and prevent wearing out of updated data.

According to our point of view, ‘Abstract’ section of the manuscript should be written after completion of the manuscript. The reason for this is that during writing process of the main text, the significant study outcomes might become insignificant or vice versa. However, generally, before onset of the writing process of the manuscript, its abstract might be already presented in various congresses. During writing process, this abstract might be a useful guide which prevents deviation from the main objective of the manuscript.

On the other hand references should be promptly put in place while writing the manuscript, Sorting, and placement of the references should not be left to the last moment. Indeed, it might be very difficult to remember relevant references to be placed in the ‘Discussion’ section. For the placement of references use of software programs detailed in other sections is a rational approach.

3. Which target journal should be selected?

In essence, the methodology to be followed in writing the ‘Discussion’ section is directly related to the selection of the target journal. Indeed, in compliance with the writing rules of the target journal, limitations made on the number of words after onset of the writing process, effects mostly the ‘Discussion’ section. Proper matching of the manuscript with the appropriate journal requires clear, and complete comprehension of the available data from scientific point of view. Previously, similar articles might have been published, however innovative messages, and new perspectives on the relevant subject will facilitate acceptance of the article for publication. Nowadays, articles questioning available information, rather than confirmatory ones attract attention. However during this process, classical information should not be questioned except for special circumstances. For example manuscripts which lead to the conclusions as “laparoscopic surgery is more painful than open surgery” or “laparoscopic surgery can be performed without prior training” will not be accepted or they will be returned by the editor of the target journal to the authors with the request of critical review. Besides the target journal to be selected should be ready to accept articles with similar concept. In fact editors of the journal will not reserve the limited space in their journal for articles yielding similar conclusions.

The title of the manuscript is as important as the structured sections * of the manuscript. The title can be the most striking or the newest outcome among results obtained.

Before writing down the manuscript, determination of 2–3 titles increases the motivation of the authors towards the manuscript. During writing process of the manuscript one of these can be selected based on the intensity of the discussion. However the suitability of the title to the agenda of the target journal should be investigated beforehand. For example an article bearing the title “Use of barbed sutures in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy shortens warm ischemia time” should not be sent to “Original Investigations and Seminars in Urologic Oncology” Indeed the topic of the manuscript is out of the agenda of this journal.

4. Do we have to get a pre-peer review about the written manuscript?

Before submission of the manuscript to the target journal the opinions of internal, and external referees should be taken. [ 1 ] Internal referees can be considered in 2 categories as “General internal referees” and “expert internal referees” General internal referees (ie. our colleagues from other medical disciplines) are not directly concerned with your subject matter but as mentioned above they critically review the manuscript as for simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness of its writing style. Expert internal reviewers have a profound knowledge about the subject, and they can provide guidance about the writing process of the manuscript (ie. our senior colleagues more experienced than us). External referees are our colleagues who did not contribute to data collection of our study in any way, but we can request their opinions about the subject matter of the manuscript. Since they are unrelated both to the author(s), and subject matter of the manuscript, these referees can review our manuscript more objectively. Before sending the manuscript to internal, and external referees, we should contact with them, and ask them if they have time to review our manuscript. We should also give information about our subject matter. Otherwise pre-peer review process can delay publication of the manuscript, and decrease motivation of the authors. In conclusion, whoever the preferred referee will be, these internal, and external referees should respond the following questions objectively. 1) Does the manuscript contribute to the literature?; 2) Does it persuasive? 3) Is it suitable for the publication in the selected journal? 4) Has a simple, clear, and effective language been used throughout the manuscript? In line with the opinions of the referees, the manuscript can be critically reviewed, and perfected. [ 1 ]**

Following receival of the opinions of internal, and external referees, one should concentrate priorly on indicated problems, and their solutions. Comments coming from the reviewers should be criticized, but a defensive attitude should not be assumed during this evaluation process. During this “incubation” period where the comments of the internal, and external referees are awaited, literature should be reviewed once more. Indeed during this time interval a new article which you should consider in the ‘Discussion’ section can be cited in the literature.

5. What are the common mistakes made related to the writing process of a manuscript?

Probably the most important mistakes made related to the writing process of a manuscript include lack of a clear message of the manuscript , inclusion of more than one main idea in the same text or provision of numerous unrelated results at the same time so as to reinforce the assertions of the manuscript. This approach can be termed roughly as “loss of the focus of the study” In conclusion, the author(s) should ask themselves the following question at every stage of the writing process:. “What is the objective of the study? If you always get clear-cut answers whenever you ask this question, then the study is proceeding towards the right direction. Besides application of a template which contains the intended clear-cut messages to be followed will contribute to the communication of net messages.

One of the important mistakes is refraining from critical review of the manuscript as a whole after completion of the writing process. Therefore, the authors should go over the manuscript for at least three times after finalization of the manuscript based on joint decision. The first control should concentrate on the evaluation of the appropriateness of the logic of the manuscript, and its organization, and whether desired messages have been delivered or not. Secondly, syutax, and grammar of the manuscript should be controlled. It is appropriate to review the manuscript for the third time 1 or 2 weeks after completion of its writing process. Thus, evaluation of the “cooled” manuscript will be made from a more objective perspective, and assessment process of its integrity will be facilitated.

Other erroneous issues consist of superfluousness of the manuscript with unnecessary repetitions, undue, and recurrent references to the problems adressed in the manuscript or their solution methods, overcriticizing or overpraising other studies, and use of a pompous literary language overlooking the main objective of sharing information. [ 4 ]

B) Approaches to the writing process of the ‘Discussion’ section:

1. how should the main points of ‘discussion’ section be constructed.

Generally the length of the ‘Discussion ‘ section should not exceed the sum of other sections (ıntroduction, material and methods, and results), and it should be completed within 6–7 paragraphs.. Each paragraph should not contain more than 200 words, and hence words should be counted repeteadly. The ‘Discussion’ section can be generally divided into 3 separate paragraphs as. 1) Introductory paragraph, 2) Intermediate paragraphs, 3) Concluding paragraph.

The introductory paragraph contains the main idea of performing the study in question. Without repeating ‘Introduction’ section of the manuscript, the problem to be addressed, and its updateness are analysed. The introductory paragraph starts with an undebatable sentence, and proceeds with a part addressing the following questions as 1) On what issue we have to concentrate, discuss or elaborate? 2) What solutions can be recommended to solve this problem? 3) What will be the new, different, and innovative issue? 4) How will our study contribute to the solution of this problem An introductory paragraph in this format is helpful to accomodate reader to the rest of the Discussion section. However summarizing the basic findings of the experimental studies in the first paragraph is generally recommended by the editors of the journal. [ 5 ]

In the last paragraph of the Discussion section “strong points” of the study should be mentioned using “constrained”, and “not too strongly assertive” statements. Indicating limitations of the study will reflect objectivity of the authors, and provide answers to the questions which will be directed by the reviewers of the journal. On the other hand in the last paragraph, future directions or potential clinical applications may be emphasized.

2. How should the intermediate paragraphs of the Discussion section be formulated?

The reader passes through a test of boredom while reading paragraphs of the Discussion section apart from the introductory, and the last paragraphs. Herein your findings rather than those of the other researchers are discussed. The previous studies can be an explanation or reinforcement of your findings. Each paragraph should contain opinions in favour or against the topic discussed, critical evaluations, and learning points.

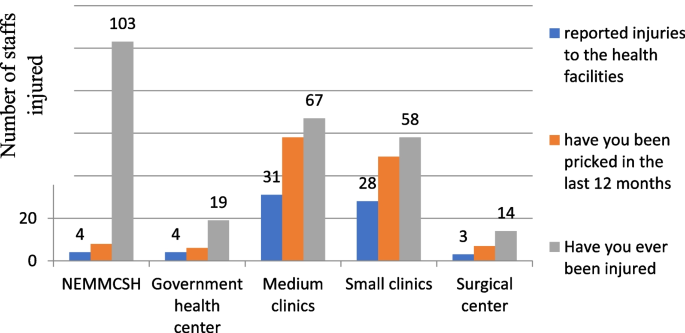

Our management approach for intermediate paragraphs is “divide and conquer” tactics. Accordingly, the findings of the study are determined in order of their importance, and a paragraph is constructed for each finding ( Figure 1 ). Each paragraph begins with an “indisputable” introductory sentence about the topic to be discussed. This sentence basically can be the answer to the question “What have we found?” Then a sentence associated with the subject matter to be discussed is written. Subsequently, in the light of the current literature this finding is discussed, new ideas on this subject are revealed, and the paragraph ends with a concluding remark.

Divide and Conquer tactics

In this paragraph, main topic should be emphasized without going into much detail. Its place, and importance among other studies should be indicated. However during this procedure studies should be presented in a logical sequence (ie. from past to present, from a few to many cases), and aspects of the study contradictory to other studies should be underlined. Results without any supportive evidence or equivocal results should not be written. Besides numerical values presented in the Results section should not be repeated unless required.

Besides, asking the following questions, and searching their answers in the same paragraph will facilitate writing process of the paragraph. [ 1 ] 1) Can the discussed result be false or inadequate? 2) Why is it false? (inadequate blinding, protocol contamination, lost to follow-up, lower statistical power of the study etc.), 3) What meaning does this outcome convey?

3. What are the common mistakes made in writing the Discussion section?:

Probably the most important mistake made while writing the Discussion section is the need for mentioning all literature references. One point to remember is that we are not writing a review article, and only the results related to this paragraph should be discussed. Meanwhile, each word of the paragraphs should be counted, and placed carefully. Each word whose removal will not change the meaning should be taken out from the text.” Writing a saga with “word salads” *** is one of the reasons for prompt rejection. Indeed, if the reviewer thinks that it is difficult to correct the Discussion section, he/she use her/ his vote in the direction of rejection to save time (Uniform requirements for manuscripts: International Comittee of Medical Journal Editors [ http://www.icmje.org/urm_full.pdf ])

The other important mistake is to give too much references, and irrelevancy between the references, and the section with these cited references. [ 3 ] While referring these studies, (excl. introductory sentences linking indisputable sentences or paragraphs) original articles should be cited. Abstracts should not be referred, and review articles should not be cited unless required very much.

4. What points should be paid attention about writing rules, and grammar?

As is the case with the whole article, text of the Discussion section should be written with a simple language, as if we are talking with our colleague. [ 2 ] Each sentence should indicate a single point, and it should not exceed 25–30 words. The priorly mentioned information which linked the previous sentence should be placed at the beginning of the sentence, while the new information should be located at the end of the sentence. During construction of the sentences, avoid unnecessary words, and active voice rather than passive voice should be used.**** Since conventionally passive voice is used in the scientific manuscripts written in the Turkish language, the above statement contradicts our writing habits. However, one should not refrain from beginning the sentences with the word “we”. Indeed, editors of the journal recommend use of active voice so as to increase the intelligibility of the manuscript.

In conclusion, the major point to remember is that the manuscript should be written complying with principles of simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness. In the light of these principles, as is the case in our daily practice, all components of the manuscript (IMRAD) can be written concurrently. In the ‘Discussion’ section ‘divide and conquer’ tactics remarkably facilitates writing process of the discussion. On the other hand, relevant or irrelevant feedbacks received from our colleagues can contribute to the perfection of the manuscript. Do not forget that none of the manuscripts is perfect, and one should not refrain from writing because of language problems, and related lack of experience.

Instead of structured sections of a manuscript (IMRAD): Introduction, Material and Methods, Results, and Discussion

Instead of in the Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine posters to be submitted in congresses are time to time discussed in Wednesday meetings, and opinions of the internal referees are obtained about the weak, and strong points of the study

Instead of a writing style which uses words or sentences with a weak logical meaning that do not lead the reader to any conclusion

Instead of “white color”; “proven”; nstead of “history”; “to”. should be used instead of “white in color”, “definitely proven”, “past history”, and “in order to”, respectively ( ref. 2 )

Instead of “No instances of either postoperative death or major complications occurred during the early post-operative period” use “There were no deaths or major complications occurred during the early post-operative period.

Instead of “Measurements were performed to evaluate the levels of CEA in the serum” use “We measured serum CEA levels”

- Translation

How to write the analysis and discussion chapters in qualitative (SSAH) research

By charlesworth author services.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 11 November, 2021

While it is more common for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) researchers to write separate, distinct chapters for their data/ results and analysis/ discussion , the same sections can feel less clearly defined for a researcher in Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities (SSAH). This article will look specifically at some useful approaches to writing the analysis and discussion chapters in qualitative/SSAH research.

Note : Most of the differences in approaches to research, writing, analysis and discussion come down, ultimately, to differences in epistemology – how we approach, create and work with knowledge in our respective fields. However, this is a vast topic that deserves a separate discussion.

Look for emerging themes and patterns

The ‘results’ of qualitative research can sometimes be harder to pinpoint than in quantitative research. You’re not dealing with definitive numbers and results in the same way as, say, a scientist conducting experiments that produce measurable data. Instead, most qualitative researchers explore prominent, interesting themes and patterns emerging from their data – that could comprise interviews, textual material or participant observation, for example.

You may find that your data presents a huge number of themes, issues and topics, all of which you might find equally significant and interesting. In fact, you might find yourself overwhelmed by the many directions that your research could take, depending on which themes you choose to study in further depth. You may even discover issues and patterns that you had not expected , that may necessitate having to change or expand the research focus you initially started off with.

It is crucial at this point not to panic. Instead, try to enjoy the many possibilities that your data is offering you. It can be useful to remind yourself at each stage of exactly what you are trying to find out through this research.

What exactly do you want to know? What knowledge do you want to generate and share within your field?

Then, spend some time reflecting upon each of the themes that seem most interesting and significant, and consider whether they are immediately relevant to your main, overarching research objectives and goals.

Suggestion: Don’t worry too much about structure and flow at the early stages of writing your discussion . It would be a more valuable use of your time to fully explore the themes and issues arising from your data first, while also reading widely alongside your writing (more on this below). As you work more intimately with the data and develop your ideas, the overarching narrative and connections between those ideas will begin to emerge. Trust that you’ll be able to draw those links and craft the structure organically as you write.

Let your data guide you

A key characteristic of qualitative research is that the researchers allow their data to ‘speak’ and guide their research and their writing. Instead of insisting too strongly upon the prominence of specific themes and issues and imposing their opinions and beliefs upon the data, a good qualitative researcher ‘listens’ to what the data has to tell them.

Again, you might find yourself having to address unexpected issues or your data may reveal things that seem completely contradictory to the ideas and theories you have worked with so far. Although this might seem worrying, discovering these unexpected new elements can actually make your research much richer and more interesting.

Suggestion: Allow yourself to follow those leads and ask new questions as you work through your data. These new directions could help you to answer your research questions in more depth and with greater complexity; or they could even open up other avenues for further study, either in this or future research.

Work closely with the literature

As you analyse and discuss the prominent themes, arguments and findings arising from your data, it is very helpful to maintain a regular and consistent reading practice alongside your writing. Return to the literature that you’ve already been reading so far or begin to check out new texts, studies and theories that might be more appropriate for working with any new ideas and themes arising from your data.

Reading and incorporating relevant literature into your writing as you work through your analysis and discussion will help you to consistently contextualise your research within the larger body of knowledge. It will be easier to stay focused on what you are trying to say through your research if you can simultaneously show what has already been said on the subject and how your research and data supports, challenges or extends those debates. By drawing from existing literature , you are setting up a dialogue between your research and prior work, and highlighting what this research has to add to the conversation.

Suggestion : Although it might sometimes feel tedious to have to blend others’ writing in with yours, this is ultimately the best way to showcase the specialness of your own data, findings and research . Remember that it is more difficult to highlight the significance and relevance of your original work without first showing how that work fits into or responds to existing studies.

In conclusion

The discussion chapters form the heart of your thesis and this is where your unique contribution comes to the forefront. This is where your data takes centre-stage and where you get to showcase your original arguments, perspectives and knowledge. To do this effectively needs you to explore the original themes and issues arising from and within the data, while simultaneously contextualising these findings within the larger, existing body of knowledge of your specialising field. By striking this balance, you prove the two most important qualities of excellent qualitative research : keen awareness of your field and a firm understanding of your place in it.

Charlesworth Author Services , a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Visit our new Researcher Education Portal that offers articles and webinars covering all aspects of your research to publication journey! And sign up for our newsletter on the Portal to stay updated on all essential researcher knowledge and information!

Register now: Researcher Education Portal

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Share with your colleagues

Scientific Editing Services

Sign up – stay updated.

We use cookies to offer you a personalized experience. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

The five steps to writing a qualitative research discussion guide

Learn how to create an effective discussion guide for qualitative research by following these five steps.

Creating a qualitative research discussion guide

Editor’s note: Joanna Jones is the CEO and founder of InterQ and co-founder of InterQ Learning Labs. This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared under the title “ How to write a discussion guide for qualitative research .”

In qualitative research, the discussion guide is the fundamental document that outlines the questions that the interviewer asks a participant or group of participants. This article focuses on discussion guides that are used in interview-based research, not on platforms (for example, mobile ethnography platforms, bulletin boards or online diaries). Although, keep in mind that the best platform research ends with an in-depth interview or group discussion, so a discussion guide will come after the first phase.

Discussion guides are fundamental to good interviewing. Moderators often have various techniques with how they use guides (some digest the key questions they need to know and skip around, others follow the question outline closely), but most moderators will agree that setting up your questions first is the key to a good interview.

Before diving into the key components every discussion guide has, let me first say that discussion guides are not a script. They’re a guide – and the key to being a good moderator is to know how to let participants go on tangents and when to guide people back to the core questions. Rarely, though, are guides read through verbatim.

Step 1: Know the goal and the essential question

There is a lot of pre-work that must happen before writing a discussion guide. This includes understanding the core goals of the research, defining the outputs and aligning the stakeholders. Our process for this stage is to conduct workshops with stakeholders, but everyone has their own methods.

This initial stage is where the researcher will define what I like to call “the essential question.” In other words, if you could only learn one thing from the research, what would it be?

Additionally, you’ll want to clearly label and record the various hypotheses that are being tested. Once you know this – and the team is aligned – you’ll be able to choose the methodology, define the participant criteria and, once everyone has signed off, start on the guide. (Keep in mind this is a general description of qualitative projects and details will differ depending on the specific project goals.)

Step 2: The introduction

When a moderator begins a research discussion, the introduction is critical. This is the part where the moderator builds rapport with the participant and sets the scene.

What to include in this stage:

- The purpose of the study and the length of the interview (be sure to keep the client name out if the study is being done blindly).

- Confidentiality details: If it’s being recorded, how it will be used and what information will be shared with whom.

- The length of the study.

- Ground rules (this is mostly used in focus groups or co-creation groups): Not trying to build consensus, letting everyone speak, participants can discuss ideas with each other as well as the moderator.

Once the key expectations are covered, it’s then good to add in a sort of icebreaker or non-study related question to get the group members or the individual participant to relax. For example, you can ask people what their dream car is or where they most want to travel. I typically try to tie the ice-breaker question to the study theme.

Step 3: Ask general questions about the topic

Discussion guides can be seen as an upside down triangle: Start general at the top and get narrower as you go along.

The next goal is to set the scene by asking general questions about the topic. This phase helps build empathy and slowly invites the participant(s) into the topic. A key component here is that you want the participants to define and name their perceptions of the category before you name it. This is a great opportunity to add in projective techniques. A favorite one that I typically do at this stage – if I’m leading groups – is an association exercise. I’ll write down a few words related to the topic on a board and have everyone write down all the associations they have with the category on sticky notes. They first write it down individually, so as not to bias each other – and then we collect the stickies and discuss as a group. This brings everyone in and sets the tone. It also gives the moderator context and helps them be grounded in the category knowledge or opinions.

Step 4: Ask specific questions and conduct activities

Once participants have defined the category and the researcher has set the scene, the discussion guide then moves into the next section: the specifics. If the study is a user test, this is where the moderator has the participant move through the product design. If it’s a focus group, the researcher will start to hone-in on the essential question that was defined at the outset of the study. This is where moderator training is so crucial. Good moderators know how to probe, guide and ask non-leading questions – while still capturing how people think, feel and do. Projective techniques and exercises are also commonly used in this phase.

Step 5: Close the interview

As the interview winds down, this is where the researcher has a chance to share the brand name to test perceptions. If it’s a completely blind study, this last phase of the discussion guide is to close the loop. For example, how would the participant rate the concepts? Where would the participant expect to purchase the product? What type of media outlets does the participant pay attention to (to test brand placement)? How is the decision-making done at an organization (to understand the buying process)? The closing section is crucial as it allows the moderator to capture more direct responses without leading the participant, since the categories and initial perceptions/ideas were captured organically – with the participant defining the terms – in the very beginning of the interview.

Discussion guides are important

To close, expect to spend five to eight hours developing your discussion guide. How the questions are set up, the order of the questions and, super important – the exercises included in the interview – require creativity and thought to put together.

Once the guide is together, practice and know it well – this will help you skip around if the participant brings up topics before you get to them. When appropriate, be able to skip around as well as probe on ideas that are the most pertinent to the study’s objectives.