Prejudiced thoughts run through all our minds — the key is what we do with them

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

We tend to think of prejudice as something that other people, particularly bad people, have in their hearts and minds.

The truth is, prejudice is inside us all. The good news is that psychology provides a powerful way to combat it.

Prejudice is due in part to cultural learning, from our parents, our schools and social messages and depictions in the media. But prejudice is also deeply embedded into our thought networks. Numerous studies have been done on implicit bias , the negative stereotyping and othering that we are not consciously aware of.

Whether we like it or not, prejudice easily digs into us. So if we’re going to combat it, we need to change how our minds deal with it.

Since I was a young child, I’ve been pained by the brutality of prejudice and how it impacts us all. I’ve also learned how profoundly it shaped the lives of my Jewish ancestors, and I’ve witnessed it directed at my children who are multiracial.

Growing up, I did not know that my mother had been told by her father — who had become swept up by the fervor of Hitler-era Germany — never to tell anyone she had “tainted blood.” My mother’s name was not Ruth Eileen Dreyer, as she claimed, but Ruth Esther Dreyer. It was only later I learned that fact and that half of her maternal aunts and uncles died crowded into “shower rooms” meant not to cleanse them, but to cleanse the world of them.

I first encountered prejudice in my childhood friend Tom, who was white like me. He spewed venom about people of other races and ethnicities, calling them the n-word and other foul names. It bothered me, and I even got into a fistfight with him over it.

Regardless of my contempt for them, his slurs sank into my mind. One day, Tom and I — along with our friend Joe — rode our bikes to a bowling alley to play a game.

As we set up, Tom strangely commented, “It looks like rain.” He and Joe giggled. I was confused. From where we were, we couldn’t see the outside.

“It looks like raaaain,” Tom repeated loudly as he and Joe tried to repress their laughter.

Finally, I noticed a Black man walking toward us — a dark cloud was rolling in. Get it?

I was horrified, and I felt sick to my stomach. But the thought also flittered into my mind that I was glad they weren’t making fun of me.

Flash forward a couple of decades. My then-teenage daughter Camille was dressed up for a school dance, looking absolutely wonderful. She is Afro-Latina-American (my first wife was Latina, Camille was her child from a previous relationship, and I adopted her).

As I watched her approach, a voice bubbled up inside my head, unbidden and unwelcome. The auditory equivalent of a smirk, it was Tom’s voice, saying very clearly, “It looks like raaaain.”

Last year, I told the story of Tom’s voice popping into my head to Camille.

Her response was sweet and pure. “I love you, Daddy,” she said. “We all have burdens like that to carry.”

Yes, we do.

Negative stereotypes pervade people’s lives. Even if you hate them — or are the victim of them — they are in your cognitive network. That means they are available to do mischief, even when you’re not conscious of it. If you go to the rigid, defended, frightened, angry, judgmental parts of your own heart, you will see that bias resides there.

But you can learn to use that recognition, and apply it to reduce the harmful impact of that part of you and the chance that your privilege and prejudice could be passed to others. By applying the practices of acceptance and commitment therapy — which focus on cultivating psychological flexibility rather than struggle and avoidance — to investigate your implicit biases, you become more aware of them and bring your actions in line with your conscious beliefs. This kind of mindful awareness allows prejudicial thoughts to become less dominant, and studies show it can even help us commit to positive actions to combat prejudice.

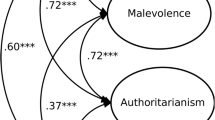

My lab researched this. We studied many forms of prejudice, including gender bias, weight bias, bias based on sexual orientation, ethnicity and more. We expected to find a common core, and we did.

We found that all forms of prejudice can be largely explained by what’s called authoritarian distancing — the belief that we are different from some group of “others” and because they are different, they represent a threat that we need to control.

When my lab examined the psychological factors led some people to settle into authoritarian distancing, we found three key characteristics:

- the relative inability to take the perspective of other people;

- the inability to feel the pain of others when you do take their perspective;

- the inability to be emotionally open to the pain of others when you do feel it.

Drawing on our findings, we developed interventions that have been found to significantly reduce prejudice.

In some ways, the most difficult to eradicate forms of bias are invisible and unconscious because they are based on privilege. For example, a white person can honestly say “I don’t think about race”, but she’s not aware of how much that exudes privilege when her Black neighbor has no choice but to think about it — she sends her teenage son out into the world every day, knowing that he is more likely to be arrested or shot at because he is Black.

Similarly, a man can believe that he is without gender bias but still talk more than — and over — his women colleagues in meetings.

Because it’s unfair and irresponsible to ask those who bear the costs of privilege to do all the heavy lifting to correct it, the first step is to look at your own behavior. Try to notice your indirect indicators of bias — the times in which your supposedly unbiased actions are actually rooted and shaped by your privilege.

As you’re doing this, ask people who are close to you and who’ve experienced bias if they can help you. For example, when I start mansplaining, my wife gives me a look. Do not expect this to feel good, but it’s a worthy journey.

Here are 3 steps that you can take to start recognizing and disarming your own prejudice:

1. Own your bias

Observe any tendencies to judge others or yourself or to enact bias based on privilege. Bring as much self-compassion and emotional openness to that awareness as you can. When do you notice prejudicial thoughts or biased actions popping up?

Let go of any tendency to buy into your judgement or make them more important by avoiding them or criticizing yourself for hosting them. These are thoughts, feelings, and invisible habits, and they are yours. You are responsible, but you are not to blame.

Just note their existence and increase your awareness of the negative cultural programming that we all carry.

2. Connect with other people’s perspective

Deliberately take the perspective of those whom your mind judges, feeling what it’s like to be subjected to stigma and bias, sometimes without conscious awareness by the person doing harm.

Don’t run from the pain of seeing those costs, or allow it to slip into guilt or shame. The goal is connection and ownership.

Allow the pain of being judged or being hurt to penetrate you. As you do, bring your awareness to how causing anyone that kind of pain goes against your values.

3. Commit to change

Channel the discomfort of ownership and the pain of connection into a motivation to act. Commit to concrete steps that you can take to reduce the effect of prejudice and stigma on others.

This could mean learning to listen more; speaking out when another person makes light of prejudice; stepping back so others can step forward; joining an advocacy group; getting to know people who belong to groups that your mind judges.

Taking these actions is not meant to erase what you are carrying and experiencing but to channel those feelings toward expressing compassion.

You can practice these steps regularly. As you begin to loosen the grip of your implicit biases, you’ll find that your enjoyment of being with people of all kinds increases, no matter how different they may have once seemed to you.

The sad fact is if we’re not helping solve the problem of prejudice, we are helping to perpetuate it. And if we don’t learn to acknowledge our privilege or catch the subtly prejudicial thoughts that go through our minds, we are supporting bias — and potentially passing it on.

It’s hard to admit to ourselves that we’ve been complicit, and it’s hard to diminish the impact of bias. But with work, we can do it.

Excerpted with permission from the new book A Liberated Mind: How to Pivot Towards What Matters by Steven C. Hayes. Published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC. © 2020 by Steven C. Hayes.

Watch his TEDxUniversityofNevada Talk here:

About the author

Steven C. Hayes, PhD , is a professor of psychology at the University of Nevada, Reno. The author of 43 books and more than 600 scientific articles, he has served as president of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy and the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science, and is one of the most cited psychologists in the world. Dr. Hayes initiated the development of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and of Relational Frame Theory (RFT), the approach to cognition on which ACT is based.

- book excerpt

- steven hayes

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

6 ways to give that aren't about money

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

How do top athletes get into the zone? By getting uncomfortable

6 things people do around the world to slow down

Creating a contract -- yes, a contract! -- could help you get what you want from your relationship

Could your life story use an update? Here’s how to do it

6 tips to help you be a better human now

How to have better conversations on social media (really!)

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

Is empathy overrated?

How literature -- yes, literature -- can help you better connect with others

The fastest way to fight prejudice? Open up

Why we need to call out casual racism

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Our Concept and Definition of Critical Thinking

|

| ||

| attempts to reason at the highest level of quality in a fair-minded way. People who think critically consistently attempt to live rationally, reasonably, empathically. They are keenly aware of the inherently flawed nature of human thinking when left unchecked. They strive to diminish the power of their egocentric and sociocentric tendencies. They use the intellectual tools that critical thinking offers – concepts and principles that enable them to analyze, assess, and improve thinking. They work diligently to develop the intellectual virtues of intellectual integrity, intellectual humility, intellectual civility, intellectual empathy, intellectual sense of justice and confidence in reason. ~ Linda Elder, September 2007 | ||

It is sending your message ...

Aug 26, 2024

Prejudice and Education in the 21st Century

March 20, 2018.

Conrad Hughes takes the conversation further into the what and how of prejudice, as well as how 21st-century education can combat prejudice.

illustration by Daniel Stolle

By conrad hughes, 20/03/ 2018.

Prejudice is a negative overgeneralization of another person or group. It comes from the Latin, meaning to pre-judge. Whereas a stereotype is a mere overgeneralization that one holds as an idea, prejudice takes the stereotype a step further by applying it negatively to real-life members of a social group in thoughts and language. When prejudice is translated into action, it can become discrimination or worse.

We are cognitively, socially, and culturally disposed to be prejudiced. Our brains work by classification and we tend to quickly reduce individuals to crude social categories in order to judge those individuals as friend or foe. This activity, in the early, reptilian part of our brain, happens more quickly than we are aware. Feelings of insecurity, threat, and fear often well up inside us and express themselves in the form of an instinct toward self-preservation which always prioritizes and favors the in-group at the expense of the out-group.

Even at the level of the cortex, where information is processed and we are capable of abstract thinking, deliberate evaluation, and weighted reflection, our working memory capacity is fairly weak, meaning that we struggle to hold onto pluralistic representations or multiple identities without forgetting some of them and reducing the thing perceived into a single entity. This is what happens when we reduce someone to one element of his/her being, for example, profession, gender, ethnic group, ideological preferences, beliefs, or nationality. Furthermore, we are perceptually predisposed to exaggerate differences between groups and minimize differences within groups, always imagining that we are like those in our group and different from those who are not in our group when in reality, differences and similarities might be the same within and across group members.

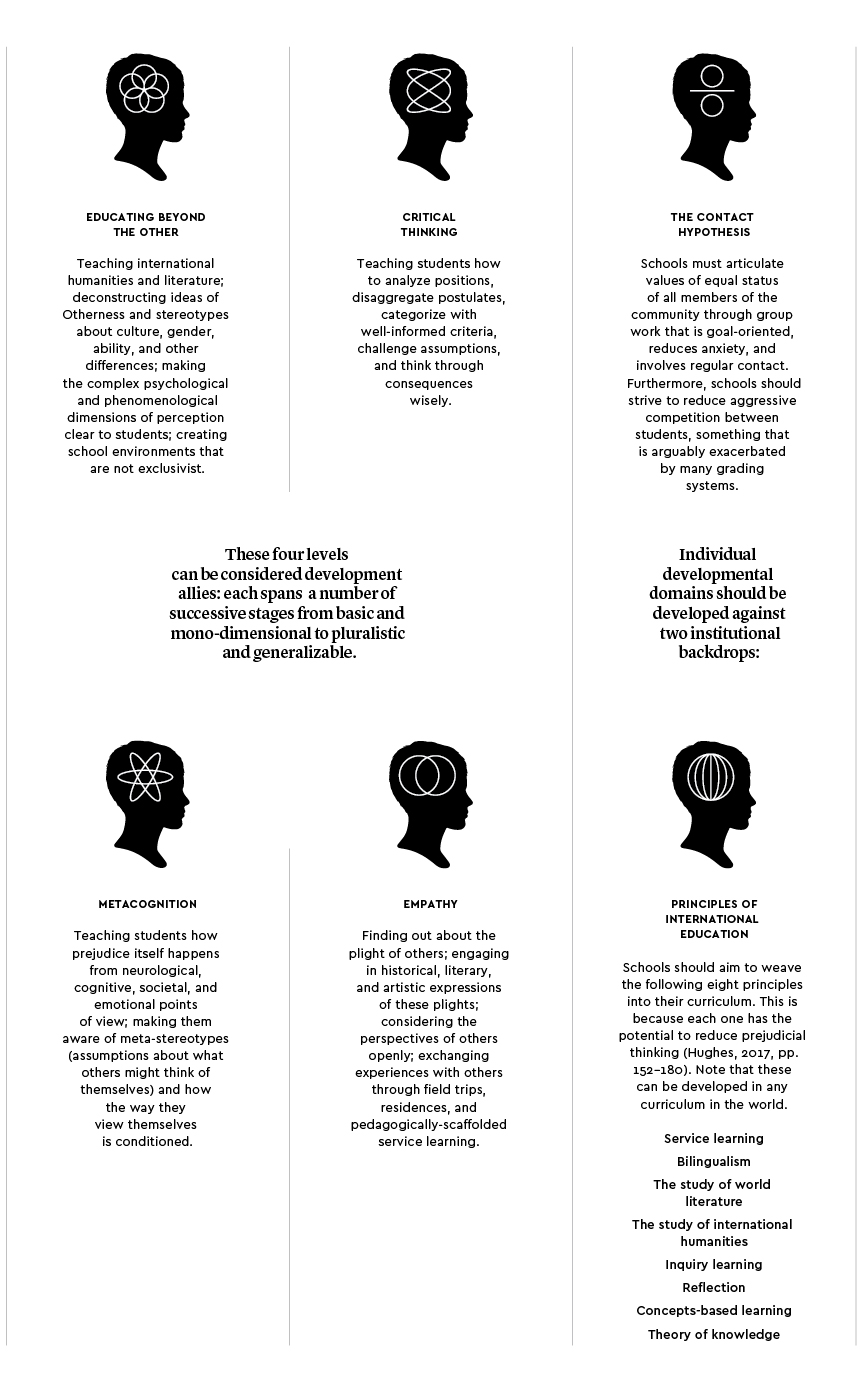

Therefore, like all sophisticated and powerful educational efforts, reducing prejudice requires a conscious effort to go beyond intuitive, lazy thinking and primal instincts; it is an act of the will involving critical thinking, self-analysis, metacognition, and deliberate selflessness—things that might not come naturally to us and have to be worked on.

School children writing in classroom. Photograph: Alamy

Prejudice on the rise

The second decade of the 21st century is full of paradox. On the one hand, one might argue that globalization and social media have brought people closer together than ever. Travel is far more accessible than it has ever been and material comfort is attainable for an increasing number of people. This would suggest that relationships across frontiers are easier to form than ever before. On the other hand, few could disagree that we have witnessed a surge of extremist thinking in right-wing demagogy, xenophobic rhetoric, and fundamentalism across the planet. As the planet’s biocapacity wanes, wealth and income inequality rise, and human resources become increasingly scarce, the idea of living together peacefully seems fragile.

Examples of prejudice and discrimination are so rife that one struggles to know where to begin. The US Department of Justice (2014) recorded over 220,000 cases of hate crimes every year from 2004 to 2012; the UK Home Office (Creese and Lader, 2014) reported that “in 2013/14, there were 44,480 hate crimes recorded by the police, an increase of five per cent compared with 2012/13, of which 37,484 (84%) were race hate crimes”. Before Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf was republished in Germany in 2016, over 15,000 people had placed orders (Addady, 2016). The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States points to a sorry state of affairs while anti-Islamic rhetoric is at a height in Europe and the United States. Albinos, Aborigines, Roma, Jews, and homosexuals still suffer from severe prejudice across the globe, while women throughout the world are the victims of lower salaries and conjugal violence. We are also deep in the throes of an uninhibited, post-politically–correct type of prejudice where racist, xenophobic, misogynistic, and bigoted statements are made in the public forum in the name of a sort of aggressive, liberated freedom of speech.

The phenomenon of the Internet has allowed anonymized, disinhibited discourse to proliferate on postings and messages. Anyone knows by trawling through the comments posted at the end of an article or YouTube video that discussions quickly veer into extremist language and propositions, as if to suggest that there is a deep-seated need to engage in profanity and verbal violence as a type of expiation or catharsis. Furthermore, confirmation bias is easy: a determined user can find some form of reported evidence proving one theory or another on the Internet, making it an easy repository of justification that the prejudiced person can cherry-pick at will. For example, statistics on crime are often used by right-wing politicians to slander ethnic minorities but are rarely put in their proper context of socioeconomic and demographic pressure.

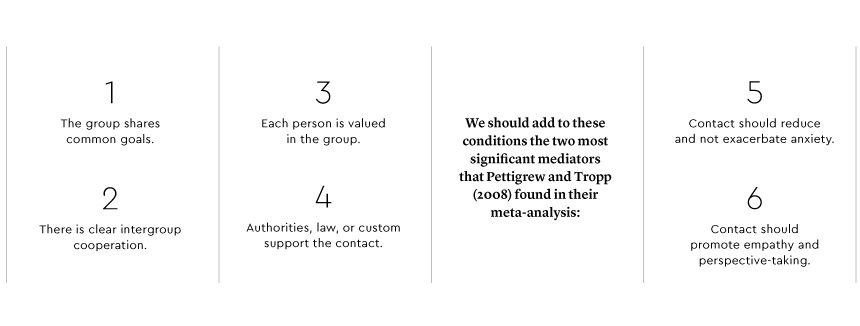

The contact hypothesis

In 1954, Gordon Allport articulated his contact hypothesis in The Nature of Prejudice , his detailed study of prejudice from the perspective of social psychology. The theory remains a reference because it has been tested extensively with significant results over more than 50 years. Allport’s hypothesis states that we can lessen prejudice if people of different backgrounds come together and make contact, provided that four conditions are present:

Social psychology tells us that if environments are created where people can work together as a team on a collective goal under clearly articulated values that celebrate the equal value of each person, prejudice will be reduced. However, if people of different backgrounds are thrown together without any mediating strategies, there is a high likelihood that they will resort to stereotypes, then to prejudice, then to antilocution, and finally to violence, especially if the environment is highly competitive (as it often is in schools). Indeed, the intuitive idea that pluralistic or multicultural environments will lead to peaceful self-regulated appreciation of difference is wrong; ground rules are needed alongside a strong institutional message against prejudicial thinking and discriminatory practice.

An education for less prejudice

The Delors Report (UNESCO, 1996) describes four pillars of education: learning to learn, learning to do, learning to be, and learning to live together. If these are the basis of meaningful education, then learning how to reduce prejudice is surely a fundamental, ongoing goal. Reducing prejudice means reducing barriers that stand in the way of self-awareness, social cohesion, open-mindedness, and the growth mindset needed to open new opportunities to work with different people.

In my recently published book, Understanding Prejudice and Education: The Challenge for Future Generations (Routledge, 2017), I synthesized research in social psychology, cognitive psychology, critical thinking, and international education to present a model that can be adapted and adopted according to context. Each area should be self-assessed using criterion-referenced descriptors. Four areas need to be emphasized at an individual level:

We will never eradicate prejudice (it’s in our DNA), but we can reduce it if schools, instructors, and learners can openly discuss what prejudice means to them and learn about other people and the world in a reflective, open-minded, pluralistic manner. If we wish to make the world a better place, then a sure place to start is with the way that human beings see and treat each other, something that can be made more humane, nuanced, and restorative if it is taken seriously in the educational agenda.

Addady, M. (2016, Jan. 11). Mein Kampf is the hottest book in Germany. Fortune .

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Creese, B., & Lader, D. (2014). Hate crimes, England and Wales, 2013/14 . Home Office Statistical Bulletin. London: Home Office.

Hughes, C. (2016). Understanding prejudice and education: The challenge for future generations. Oxford: Routledge.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology , 38 , 922-934.

UNESCO (1996). Learning: The treasure within . Paris: UNESCO.

US Department of Justice, Office of Justice (2014). Hate crime victimization , 2004–2012: Statistical tables . Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Stereotypes and prejudice.

- David Marx David Marx San Diego State University, Department of Psychology

- and Sei Jin Ko Sei Jin Ko San Diego State University, Department of Psychology

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.307

- Published online: 23 May 2019

Stereotypes are widely held generalized beliefs about the behaviors and attributes possessed by individuals from certain social groups (e.g., race/ethnicity, sex, age, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation). They are often unchanging even in the face of contradicting information; however, they are fluid in the sense that stereotypic beliefs do not always come to mind or are expressed unless a situation activates the stereotype. Stereotypes generally serve as an underlying justification for prejudice, which is the accompanying feeling (typically negative) toward individuals from a certain social group (e.g., the elderly, Asians, transgender individuals). Many contemporary social issues are rooted in stereotypes and prejudice; thus research in this area has primarily focused on the antecedents and consequences of stereotype and prejudice as well as the ways to minimize the reliance on stereotypes when making social judgments.

- stereotypes

- stereotype activation

- implicit bias

- prejudice reduction

- implicit measures

- explicit measures

- stereotype maintenance

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 26 August 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 04 September 2014

The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping

- David M. Amodio 1

Nature Reviews Neuroscience volume 15 , pages 670–682 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

284 Citations

309 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Decision making

- Functional magnetic resonance imaging

- Social neuroscience

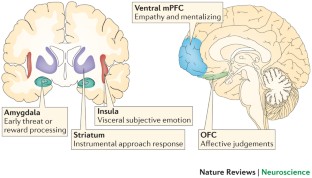

Prejudice is a fundamental component of human social behaviour that represents the complex interplay between neural processes and situational factors. Hence, the domain of intergroup bias, which encompasses prejudice, stereotyping and the self-regulatory processes they often elicit, offers an especially rich context for studying neural processes as they function to guide complex social behaviour.

The sociocognitive processes involved in prejudice, stereotyping and the regulation of intergroup responses engage different sets of neural structures that seem to comprise separate functional networks.

Prejudice is an evaluation of, or an emotional response towards, a social group based on preconceptions. Prejudiced responses range from the rapid detection of threat or coalition and subjective visceral responses to deliberate evaluations and dehumanization — processes that are supported most directly by the amygdala, orbital frontal cortex, insula, striatum and medial prefrontal cortex.

Stereotypes represent the cognitive component of intergroup bias — the conceptual attributes associated with a particular social group. Stereotyping involves the encoding of group-based concepts and their influence on impression formation, social goals and behaviour. These processes are primarily underpinned by the anterior temporal lobes and the medial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices.

Expressions of prejudice and stereotyping are often regulated on the basis of personal beliefs and social norms. This regulatory process involves neural structures that are typically recruited for cognitive control, such as the dorsal anterior cingulate and lateral prefrontal cortices, as well as structures supporting mentalizing and perspective taking, such as the rostral anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortices.

Situated at the interface of the natural and social sciences, the neuroscience of prejudice offers a unique context for understanding complex social behaviour and an opportunity to apply neuroscientific advances to pressing social issues.

Despite global increases in diversity, social prejudices continue to fuel intergroup conflict, disparities and discrimination. Moreover, as norms have become more egalitarian, prejudices seem to have 'gone underground', operating covertly and often unconsciously, such that they are difficult to detect and control. Neuroscientists have recently begun to probe the neural basis of prejudice and stereotyping in an effort to identify the processes through which these biases form, influence behaviour and are regulated. This research aims to elucidate basic mechanisms of the social brain while advancing our understanding of intergroup bias in social behaviour.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

176,64 € per year

only 14,72 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The neural representation of stereotype content

Neural dynamics of racial categorization predicts racial bias in face recognition and altruism

Integrating stereotypes and factual evidence in interpersonal communication

Brewer, M. B. The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 55 , 429–444 (1999).

Google Scholar

Ito, T. A. & Urland, G. R. Race and gender on the brain: electrocortical measures of attention to the race and gender of multiply categorizable individuals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85 , 616–626 (2003).

PubMed Google Scholar

Ratner, K. G. & Amodio, D. M. Seeing “us versus them”: minimal group effects on the neural encoding of faces. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49 , 298–301 (2013).

Allport, G. W. The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, 1954).

Fiske, S. T. in The Handbook of Social Psychology Vol. 2 , 4th edn (eds Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T. & Lindzey, G.) 357–411 (McGraw Hill, 1998).

Amodio, D. M. & Devine, P. G. Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91 , 652–661 (2006).

Devine, P. G. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56 , 5–18 (1989).

Fazio, R. H., Jackson, J. R., Dunton, B. C. & Williams, C. J. Variability in automatic activation as an unobtrusive measure of racial attitudes: a bona fide pipeline? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69 , 1013–1027 (1995).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 102 , 4–27 (1995).

Amodio, D. M. The social neuroscience of intergroup relations. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 19 , 1–54 (2008).

Ito, T. A. & Bartholow, B. D. The neural correlates of race. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13 , 524–531 (2009). In a field dominated by fMRI studies, this review presents important research on ERP approaches to probing the neural underpinnings of sociocognitive processes involved in prejudice and stereotyping.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kubota, J. T., Banaji, M. R. & Phelps, E. A. The neuroscience of race. Nature Neurosci. 15 , 940–948 (2012).

Amodio, D. M. Can neuroscience advance social psychological theory? Social neuroscience for the behavioral social psychologist. Soc. Cogn. 28 , 695–716 (2010).

Poldrack, R. A. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends Cogn. Sci. 10 , 59–63 (2006).

Mackie, D. M. & Smith, E. R. in The Social Self: Cognitive, Interpersonal, and Intergroup Perspectives (eds Forgas, J. P. & Williams, K. D.) 309–326 (Psychology Press, 2002).

Cottrell, C. A. & Neuberg, S. L. Different emotional reactions to different groups: a sociofunctional threat-based approach to “prejudice”. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88 , 770–789 (2005).

Swanson, L. W. & Petrovich, G. D. What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci. 21 , 323–331 (1998).

LeDoux, J. E. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23 , 155–184 (2000).

Davis, M. Neural systems involved in fear and anxiety measured with fear-potentiated startle. Am. Psychol. 61 , 741–756 (2006).

Fendt, M. & Fanselow, M. S. The neuroanatomical and neurochemical basis of conditioned fear. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 23 , 743–760 (1999).

LeDoux, J. E., Iwata, J., Cicchetti, P. & Reis, D. J. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J. Neurosci. 8 , 2517–2529 (1988).

Holland, P. C. & Gallagher, M. Amygdala circuitry in attentional and representational processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 3 , 65–73 (1999).

Rolls, E. T. & Rolls, B. J. Altered food preferences after lesions in the basolateral region of the amygdala in the rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 83 , 248–259 (1973).

Adolphs, R. Fear, faces, and the human amygdala. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 18 , 166–172 (2008).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Phelps, E. A. et al. Performance on indirect measures of race evaluation predicts amygdala activation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12 , 729–738 (2000). An early fMRI investigation of neural correlates of implicit prejudice, focusing on the amygdala. Relative differences in amygdala activity in response to black compared with white faces were associated with a behavioural index of implicit prejudice and startle responses to black versus white faces.

Hart, A. J. et al. Differential response in the human amygdala to racial outgroup versus ingroup face stimuli. Neuroreport 11 , 2351–2355 (2000).

Amodio, D. M., Harmon-Jones, E. & Devine, P. G. Individual differences in the activation and control of affective race bias as assessed by startle eyeblink responses and self-report. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84 , 738–753 (2003). The first reported difference in amygdala activity in response to black compared with white (and Asian) faces. By using the startle-eyeblink method to assess amygdala activity related to the CeA, the results link implicit prejudice more directly to a Pavlovian conditioning mechanism of learning and behavioural expression.

Amodio, D. M. & Ratner, K. G. A memory systems model of implicit social cognition. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20 , 143–148 (2011).

Olson, M. A. & Fazio, R. H. Reducing automatically-activated racial prejudice through implicit evaluative conditioning. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32 , 421–433 (2006).

Kawakami, K., Phills, C. E., Steele, J. R. & Dovidio, J. F. (Close) distance makes the heart grow fonder: improving implicit racial attitudes and interracial interactions through approach behaviors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92 , 957–971 (2007).

Amodio, D. M. & Hamilton, H. K. Intergroup anxiety effects on implicit racial evaluation and stereotyping. Emotion 12 , 1273–1280 (2012).

Chekroud, A. M., Everett, J. A. C., Bridge, H. & Hewstone, M. A review of neuroimaging studies of race-related prejudice: does amygdala response reflect threat? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8 , 179 (2014).

Ronquillo, J. et al. The effects of skin tone on race-related amygdala activity: an fMRI investigation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2 , 39–44 (2007).

Richeson, J. A., Todd, A. R., Trawalter, S. & Baird, A. A. Eye-gaze direction modulates race-related amygdala activity. Group Process. Interg. Relat. 11 , 233–246 (2008).

Freeman, J. B., Schiller, D., Rule, N. O. & Ambady, N. The neural origins of superficial and individuated judgments about ingroup and outgroup members. Hum. Brain Mapp. 31 , 150–159 (2010).

Forbes, C. E., Cox, C. L., Schmader, T. & Ryan, L. Negative stereotype activation alters interaction between neural correlates of arousal, inhibition, and cognitive control. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 771–781 (2012).

Cunningham, W. A. et al. Separable neural components in the processing of black and white faces. Psychol. Sci. 15 , 806–813 (2004).

Telzer, E. H., Humphreys, K., Shapiro, M. & Tottenham, N. L. Amygdala sensitivity to race is not present in childhood but emerges in adolescence. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 25 , 234–244 (2013).

Cloutier, J., Li, T. & Correll, J. The impact of childhood experience on amygdala response to perceptually familiar black and white faces. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26 , 1992–2004 (2014).

Olsson, A., Ebert, J. P., Banaji, M. R. & Phelps, E. A. The role of social group in the persistence of learned fear. Science 309 , 785–787 (2005).

Richeson, J. A. & Trawalter, S. The threat of appearing prejudiced and race-based attentional biases. Psychol. Sci. 19 , 98–102 (2008).

Ofan, R. H., Rubin, N. & Amodio, D. M. Situation-based social anxiety enhances the neural processing of faces: evidence from an intergroup context. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst087 (2013).

Plant, E. A. & Devine, P. G. Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75 , 811–832 (1998).

Stephan, W. G. & Stephan, C. W. Intergroup anxiety. J. Soc. Issues 41 , 157–175 (1985).

Lieberman, M. D., Hariri, A., Jarcho, J. M., Eisenberger, N. I. & Bookheimer, S. Y. An fMRI investigation of race-related amygdala activity in African-American and Caucasian-American individuals. Nature Neurosci. 8 , 720–722 (2005).

Wheeler, M. E. & Fiske, S. T. Controlling racial prejudice: social-cognitive goals affect amygdala and stereotype activation. Psychol. Sci. 16 , 56–63 (2005).

Van Bavel, J. J., Packer, D. J. & Cunningham, W. A. The neural substrates of in-group bias: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Psychol. Sci. 11 , 1131–1139 (2008). This study compared the independent effects of race and coalition (team membership) on amygdala responses to faces and showed that when team membership was salient, the amygdala responded to coalition (subject's team or other team) and not race (black or white). This finding demonstrated that the amygdala response to race is not inevitable but rather corresponds to the subject's particular task goal.

Richeson, J. A. et al. An fMRI investigation of the impact of interracial contact on executive function. Nature Neurosci. 6 , 1323–1328 (2003).

Gilbert, S. J., Swencionis, J. K. & Amodio, D. M. Evaluative versus trait representation in intergroup social judgments: distinct roles of anterior temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia 50 , 3600–3611 (2012). Using fMRI, the authors distinguished neural processes involved in stereotyping and prejudiced attitudes. Stereotype-based judgements of black compared with white people uniquely involved the mPFC; affect-based judgements uniquely involved the OFC.

Golby, A. J., Gabrieli, J. D. E., Chiao, J. Y. & Eberhardt, J. L. Differential fusiform responses to same- and other-race faces. Nature Neurosci. 4 , 845–850 (2001). The first demonstration of race effects in visual processing, using fMRI. Differences in fusiform responses to black and white faces predicted the degree of 'own race bias' in memory in white subjects.

Knutson, K. M., Mah, L., Manly, C. F. & Grafman, J. Neural correlates of automatic beliefs about gender and race. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28 , 915–930 (2007).

Brosch, T., Bar-David, E. & Phelps, E. A. Implicit race bias decreases the similarity of neural representations of black and white faces. Psychol. Sci. 24 , 160–166 (2013).

Schreiber, D. & Iacoboni, M. Huxtables on the brain: an fMRI study of race and norm violation. Polit. Psychol. 33 , 313–330 (2012).

Whalen, P. J. Fear, vigilance, and ambiguity: initial neuroimaging studies of the human amygdala. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 7 , 177–188 (1998).

Said, C. P., Baron, S. & Todorov, A. Nonlinear amygdala response to face trustworthiness: contributions of high and low spatial frequency information. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 , 519–528 (2009).

Cunningham, W. A., Van Bavel, J. J. & Johnsen, I. R. Affective flexibility: evaluative processing goals shape amygdala activity. Psychol. Sci. 19 , 152–160 (2008).

Phelps, E. A., Cannistraci, C. J. & Cunningham, W. A. Intact performance on an indirect measure of race bias following amygdala damage. Neuropsychologia 41 , 203–208 (2003).

Bechara, A., Damasio, H. & Damasio, A. R. Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 10 , 295–307 (2000).

O'Doherty, J., Kringelbach, M. L., Rolls, E. T., Hornak, J. & Andrews, C. Abstract reward and punishment representations in the human orbitofrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci. 4 , 95–102 (2001).

Rushworth, M. F. S., Noonan, M. P., Boorman, E. D., Walton, M. E. & Behrens, T. E. Frontal cortex and reward-guided learning and decision-making. Neuron 70 , 1054–1069 (2011).

Beer, J. S., Heerey, E. H., Keltner, D., Scabini, D. & Knight, R. T. The regulatory function of self-conscious emotion: insights from patients with orbitofrontal damage. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85 , 594–604 (2003).

Amodio, D. M. & Frith, C. D. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 7 , 268–277 (2006).

CAS Google Scholar

Ongu¨r, D. & Price, J. L. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb. Cortex 10 , 206–219 (2000).

Beer, J. S. et al. The Quadruple Process model approach to examining the neural underpinnings of prejudice. Neuroimage 43 , 775–783 (2008).

Craig, A. D. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 655–666 (2002).

Craig, A. D. How do you feel — now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 59–70 (2009).

Harris, L. T. & Fiske, S. T. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuro-imaging responses to extreme outgroups. Psychol. Sci. 17 , 847–853 (2006).

Singer, T. et al. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science 303 , 1157–1162 (2004).

Singer, T. et al. Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature 439 , 466–469 (2006).

Lamm, C., Meltzoff, A. N. & Decety, J. How do we empathize with someone who is not like us? A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22 , 362–376 (2010).

Xu, X., Zuo, X., Wang, X. & Han, S. Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. J. Neurosci. 29 , 8525–8529 (2009). In a demonstration of racial bias in empathy, mPFC and ACC activity linked to empathy was observed only when subjects viewed members of their own racial group being exposed to painful stimuli.

Cikara, M. & Fiske, S. T. Bounded empathy: neural responses to outgroup targets' (mis)fortunes. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 3791–3803 (2011).

Alexander, G. E., DeLong, M. R. & Strick, P. L. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 9 , 357–381 (1986).

Knutson, B., Adams, C. S., Fong, G. W. & Hommer, D. Anticipation of monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 21 , RC159 (2001).

O'Doherty, J. et al. Dissociable roles of ventral and dorsal striatum in instrumental conditioning. Science 304 , 452–454 (2004).

Stanley, D. A. et al. Race and reputation: perceived racial group trustworthiness influences the neural correlates of trust decisions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367 , 744–753 (2012).

Mitchell, J. P., Heatherton, T. F. & Macrae, C. N. Distinct neural systems subserve person and object knowledge. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99 , 15238–15243 (2002).

Van Overwalle, F. Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30 , 829–858 (2009).

Krueger, F., Barbey, A. K. & Grafman, J. The medial prefrontal cortex mediates social event knowledge. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13 , 103–109 (2009).

Frith, C. D. & Frith, U. Interacting minds—a biological basis. Science 286 , 1692–1695 (1999).

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E. G. & Saxe, R. Us and them: intergroup failures of empathy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20 , 149–153 (2011).

Cikara, M., Eberhardt, J. L. & Fiske, S. T. From agents to objects: sexist attitudes and neural responses to sexualized targets. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 540–551 (2011).

Hamilton, D. L. & Sherman, J. W. in Handbook of Social Cognition Vol. 2 , 2nd edn (eds Wyer, R. S. Jr & Srull, T. K.) 1–68 (Erlbaum, 1994).

Olson, I. R., McCoy, D., Klobusicky, E. & Ross, L. A. Social cognition and the anterior temporal lobes: a review and theoretical framework. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8 , 123–133 (2013).

Quadflieg, S. & Macrae, C. N. Stereotypes and stereotyping: what's the brain got to do with it? Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 22 , 215–273 (2011). A comprehensive review of neuroscience research on social stereotyping processes.

Gabrieli, J. D. Cognitive neuroscience of human memory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49 , 87–115 (1998).

Martin, A. The representation of object concepts in the brain. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58 , 25–45 (2007).

Patterson, K., Nestor, P. J. & Rogers, T. T. Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 976–987 (2007).

Quadflieg, S. et al. Exploring the neural correlates of social stereotyping. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 , 1560–1570 (2009).

Olson, I. R., Plotzker, A. & Ezzyat, Y. The enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain 130 , 1718–1731 (2007).

Zahn, R. et al. Social concepts are represented in the superior anterior temporal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 6430–6435 (2007).

de Schotten, M. T., Dell'Acqua, F., Valabregue, R. & Catani, M. Monkey to human comparative anatomy of the frontal lobe association tracts. Cortex 48 , 82–96 (2012).

Contreras, J. M., Banaji, M. R. & Mitchell, J. P. Dissociable neural correlates of stereotypes and other forms of semantic knowledge. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7 , 764–770 (2012). An fMRI study on the neural underpinnings of stereotyping that distinguishes the role of trait inference processes from that of object knowledge representation.

Gallate, J., Wong, C., Ellwood, S., Chi, R. & Snyder, A. Noninvasive brain stimulation reduces prejudice scores on an implicit association test. Neuropsychology 25 , 185–192 (2011).

Milne, E. & Grafman, J. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions in humans eliminate implicit gender stereotyping. J. Neurosci. 21 , 1–6 (2001).

Mitchell, J. P., Macrae, C. N. & Banaji, M. R. Dissociable medial prefrontal contributions to judgments of similar and dissimilar others. Neuron 50 , 655–663 (2006).

Quadflieg, S. et al. Stereotype-based modulation of person perception. Neuroimage 57 , 549–557 (2011).

Forbes, C. E. et al. Identifying temporal and causal contributions of neural processes underlying the Implicit Association Test. (IAT). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6 , 320 (2012).

Mitchell, J. P. Social psychology as a natural kind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13 , 246–251 (2009).

Gilbert, S. J. et al. Distinct regions of medial rostral prefrontal cortex supporting social and nonsocial functions. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2 , 217–226 (2007).

Baetens, K., Ma, N., Steen, J. & van Overwalle, F. Involvement of the mentalizing network in social and non-social high construal. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9 , 817–824 (2014).

Saxe, R. Uniquely human social cognition. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16 , 235–239 (2006).

Frith, C. D. & Frith, U. Implicit and explicit processes in social cognition. Neuron 60 , 503–510 (2008).

Uddin, L. Q., Iacoboni, M., Lange, C. & Keenan, J. P. The self and social cognition: the role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11 , 153–157 (2007).

Blaxton, T. A. et al. Functional mapping of human memory using PET: comparisons of conceptual and perceptual tasks. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 50 , 42–56 (1996).

Buckner, R. L. & Tulving, E. in Handbook of Neuropsychology Vol. 10 (eds Boller, F. & Grafman, J.) 439–466 (Elsevier, 1995).

Demb, J. B. et al. Semantic encoding and retrieval in the left inferior prefrontal cortex: a functional MRI study of task difficulty and process specificity. J. Neurosci. 15 , 5870–5878 (1995).

Thompson-Schill, S. L. Neuroimaging studies of semantic memory: inferring “how” from “where”. Neuropsychologia 41 , 280–292 (2003).

Miller, E. K., Freedman, D. J. & Wallis, J. D. The prefrontal cortex: categories, concepts and cognition. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 357 , 1123–1136 (2002).

Balleine, B. W., Delgado, M. R. & Hikosaka, O. The role of the dorsal striatum in reward and decision-making. J. Neurosci. 27 , 8161–8165 (2007).

Mitchell, J. P., Ames, D. L., Jenkins, A. C. & Banaji, M. R. Neural correlates of stereotype application. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 , 594–604 (2009).

Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W. & Poldrack, R. A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8 , 170–177 (2004).

Bodenhausen, G. V., Sheppard, L. & Kramer, G. P. Negative affect and social perception: the differential impact of anger and sadness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 24 , 45–62 (1994).

DeSteno, D., Dasgupta, N., Bartlett, M. Y. & Cajdric, A. Prejudice from thin air: the effect of emotion on automatic intergroup attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 15 , 319–324 (2004).

Choi, E. Y., Yeo, B. T. & Buckner, R. L. The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 108 , 2242–2263 (2012).

Bush, G., Luu, P. & Posner, M. L. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4 , 215–222 (2000).

Mansouri, F. A., Tanaka, K. & Buckley, M. J. Conflict-induced behavioral adjustment: a clue to the executive functions of the prefrontal cortex. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 141–152 (2009).

Gerhing, W. J., Goss, B., Coles, M. G. H., Meyer, D. E. & Donchin, E. A neural system for error detection and compensation. Psychol. Sci. 4 , 385–390 (1993).

Botvinick, M., Nystrom, L., Fissell, K., Carter, C. & Cohen, J. Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex. Nature 402 , 179–181 (1999).

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S. & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol. Rev. 108 , 624–652 (2001).

Shackman, A. J. et al. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 12 , 154–167 (2011).

Amodio, D. M. & Devine, P. G. in Self Control in Society, Mind and Brain (eds Hassin, R. R., Ochsner, K. N. & Trope, Y.). 49–75 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Amodio, D. M. et al. Neural signals for the detection of unintentional race bias. Psychol. Sci. 15 , 88–93 (2004). This study demonstrated the role of the ACC in the control of racial bias. Using ERPs, the authors found an increase ACC activity to stereotype-based conflict that predicted enhanced control of bias in behaviour.

Amodio, D. M., Kubota, J. T., Harmon-Jones, E. & Devine, P. G. Alternative mechanisms for regulating racial responses according to internal versus external cues. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 1 , 26–36 (2006).

Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G. & Harmon-Jones, E. Individual differences in the regulation of intergroup bias: the role of conflict monitoring and neural signals for control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94 , 60–74 (2008).

Bartholow, B. D., Dickter, C. L. & Sestir, M. A. Stereotype activation and control of race bias: cognitive control of inhibition and its impairment by alcohol. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90 , 272–287 (2006).

Correll, J., Urland, G. R. & Ito, T. A. Event-related potentials and the decision to shoot: the role of threat perception and cognitive control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 42 , 120–128 (2006).

Gonsalkorale, K., Sherman, J. W., Allen, T. J., Klauer, K. C. & Amodio, D. M. Accounting for successful control of implicit racial bias: the roles of association activation, response monitoring, and overcoming bias. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37 , 1534–1545 (2011).

Fourie, M. M., Thomas, K. G. F., Amodio, D. M., Warton, C. M. R. & Meintjes, E. M. Neural correlates of experienced moral emotion: an fMRI investigation of emotion in response to prejudice feedback. Soc. Neurosci. 9 , 203–218 (2014).

Van Nunspeet, F., Ellemers, N., Derks, B. & Nieuwenhuis, S. Moral concerns increase attention and response monitoring during IAT performance: ERP evidence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9 , 141–149 (2014).

Fuster, J. M. The prefrontal cortex—an update: time is of the essence. Neuron 2 , 319–333 (2001).

Badre, D. & D'Esposito, M. Is the rostro–caudal axis of the frontal lobe hierarchical? Nature Rev. Neurosci. 10 , 659–669 (2009).

Koechlin, E., Ody, C. & Kouneiher, F. The architecture of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science 302 , 1181–1185 (2003).

Aron, A. R. The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control. Neuroscientist 13 , 214–228 (2007).

Ghashghaei, H. T., Hilgetag, C. C. & Barbas, H. Sequence of information processing for emotions based on the anatomic dialogue between prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Neuroimage 34 , 905–923 (2007).

Amodio, D. M. Coordinated roles of motivation and perception in the regulation of intergroup responses: frontal cortical asymmetry effects on the P2 event-related potential and behavior. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22 , 2609–2617 (2010). This study demonstrated the role of the PFC in the behavioural control of racial bias and showed that this effect involves changes in early perceptual attention to racial cues. The study provided initial evidence for a 'motivated perception' account of self-regulation.

Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G. & Harmon-Jones, E. A dynamic model of guilt: implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 524–530 (2007).

Gozzi, M., Raymont, V., Solomon, J., Koenigs, M. & Grafman, J. Dissociable effects of prefrontal and anterior temporal cortical lesions on stereotypical gender attitudes. Neuropsychologia 47 , 2125–2132 (2009).

Milad, M. R. & Quirk, G. J. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 420 , 70–74 (2002).

Sloman, S. A. The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 119 , 3–22 (1996).

Kawakami, K., Dovidio, J. F., Moll, J., Hermsen, S. & Russin, A. Just say no (to stereotyping): effects of training on the negation of stereotypic associations on stereotype activation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78 , 871–888 (2000).

Mallan, K. M., Sax, J. & Lipp, O. V. Verbal instruction abolishes fear conditioned to racial out-group faces. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 , 1303–1307 (2009).

Bouton, M. E. Conditioning, remembering, and forgetting. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. B 20 , 219–231 (1994).

Devine, P. G., Plant, E. A., Amodio, D. M., Harmon-Jones, E. & Vance, S. L. The regulation of explicit and implicit racial bias: the role of motivations to respond without prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82 , 835–848 (2002).

Kleiman, T., Hassin, R. R. & Trope, Y. The control-freak mind: stereotypical biases are eliminated following conflict-activated cognitive control. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143 , 498–503 (2014).

Monteith, M. J., Ashburn-Nardo, L., Voils, C. I. & Czopp, A. M. Putting the brakes on prejudice: on the development and operation of cues for control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83 , 1029–1050 (2002).

Mendoza, S. A., Gollwitzer, P. M. & Amodio, D. M. Reducing the expression of implicit stereotypes: reflexive control through implementation intentions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36 , 512–523 (2010).

Bar, M. et al. Top-down facilitation of visual recognition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103 , 449–454 (2006).

Van Bavel, J. J., Packer, D. J. & Cunningham, W. A. Modulation of the fusiform face area following minimal exposure to motivationally relevant faces: evidence of in-group enhancement (not out-group disregard). J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 3343–3354 (2011).

Ratner, K. G., Dotsch, R., Wigboldus, D., van Knippenberg, A. & Amodio, D. M. Visualizing minimal ingroup and outgroup faces: implications for impressions, attitudes, and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106 , 897–911 (2014).

Krosch, A. K. & Amodio, D. M. Economic scarcity alters the perception of race. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 9079–9084 (2014).

Ofan, R. H., Rubin, N. & Amodio, D. M. Seeing race: N170 responses to race and their relation to automatic racial attitudes and controlled processing. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 3152–3161 (2011).

Brebner, J. L., Krigolson, O., Handy, T. C., Quadflieg, S. & Turk, D. J. The importance of skin color and facial structure in perceiving and remembering others: an electro-physiological study. Brain Res. 1388 , 123–133 (2011).

Caldara, R., Rossion, B., Bovet, P. & Hauert, C. A. Event-related potentials and time course of the 'other-race' face classification advantage. Neuroreport 15 , 905–910 (2004).

Caldara, R. et al. Face versus non-face object perception and the 'other-race' effect: a spatiotemporal event-related potential study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114 , 515–528 (2003).

Ito, T. A. & Urland, G. R. The influence of processing objectives on the perception of faces: an ERP study of race and gender perception. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 5 , 21–36 (2005).

Walker, P. M., Silvert, L., Hewstone, M. & Nobre, A. C. Social contact and other-race face processing in the human brain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 3 , 16–25 (2008).

Wiese, H., Stahl, J. & Schweinberger, S. R. Configural processing of other-race faces is delayed but not decreased. Biol. Psychol. 81 , 103–109 (2009).

Contreras, J. M., Banaji, M. R. & Mitchell, J. P. Multivoxel patterns in fusiform face area differentiate faces by sex and race. PLoS ONE 8 , e69684 (2013).

Ratner, K. G., Kaul, C. & Van Bavel, J. J. Is race erased? Decoding race from patterns of neural activity when skin color is not diagnostic of group boundaries. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8 , 750–755 (2013).

Greenwald, A. G., Poehlman, T. A., Uhlmann, E. & Banaji, M. R. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. meta-analysis of predictive validity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97 , 17–41 (2009).

Payne, B. K. Prejudice and perception: the role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81 , 181–192 (2001).

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E. & Schwartz, J. K. L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the Implicit Association Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74 , 1464–1480 (1998).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Work on this article was supported by a National Science Foundation grant (BCS 0847350). The author thanks members of the NYU Social Neuroscience Laboratory, J. Freeman, K. Ratner and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, New York University, 6 Washington Place, New York, 10003, New York, USA

David M. Amodio

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David M. Amodio .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, powerpoint slide for fig. 2, powerpoint slide for fig. 3, powerpoint slide for fig. 4, powerpoint slide for fig. 5.

Motives that operate in social contexts and satisfy basic, often universal, goals and aspirations, such as to affiliate (for example, form relationships and communities) or to achieve dominance (for example, within a social hierarchy).

Conceptual attributes associated with a group and its members (often through over-generalization), which may refer to trait or circumstantial characteristics.

Evaluations of or affective responses towards a social group and its members based on preconceptions.

The process of responding in an intentional manner, often involving the inhibition or overriding of an alternative response tendency.

The visual encoding of a face in terms of its basic structural characteristics (for example, the eyes, nose, mouth and the relative distances between these elements). Configural encoding may be contrasted with featural encoding, which refers to the encoding of feature characteristics that make an individual's face unique.

Actions performed to achieve a desired outcome (that is, goal-directed responses).

Prejudiced or stereotype-based perceptions or responses that operate without conscious awareness.

Judgements that result from thoughtful considerations (often involving cognitive control) as opposed to rapid, gut-level, 'snap' judgements.

(ERP). An electrical signal produced by summated postsynaptic potentials of cortical neurons in response to a discrete event, such as a stimulus or a response in an experimental task. Typically recorded from the scalp in humans, ERPs can be measured with extremely high temporal resolution and can be used to track rapid, real-time changes in neural activity.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Amodio, D. The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nat Rev Neurosci 15 , 670–682 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3800

Download citation

Published : 04 September 2014

Issue Date : October 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3800

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Causation in neuroscience: keeping mechanism meaningful.

- Lauren N. Ross

- Dani S. Bassett

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2024)

Implicit racial biases are lower in more populous more diverse and less segregated US cities

- Andrew J. Stier

- Sina Sajjadi

- Marc G. Berman

Nature Communications (2024)

The Role of Affective Empathy in Eliminating Discrimination Against Women: a Conceptual Proposition

- Michaela Guthridge

- Tania Penovic

- Melita J. Giummarra

Human Rights Review (2023)

Beyond Dehumanized Gender Identity: Critical Reflection on Neuroscience, Power Relationship and Law

- Chetan Sinha

Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science (2023)

Mechanisms of action for stigma reduction among primary care providers following social contact with service users and aspirational figures in Nepal: an explanatory qualitative design

- Bonnie N. Kaiser

- Dristy Gurung

- Brandon A. Kohrt

International Journal of Mental Health Systems (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

1 Introduction to Critical Thinking

I. what is c ritical t hinking [1].

Critical thinking is the ability to think clearly and rationally about what to do or what to believe. It includes the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking. Someone with critical thinking skills is able to do the following:

- Understand the logical connections between ideas.

- Identify, construct, and evaluate arguments.

- Detect inconsistencies and common mistakes in reasoning.

- Solve problems systematically.

- Identify the relevance and importance of ideas.

- Reflect on the justification of one’s own beliefs and values.

Critical thinking is not simply a matter of accumulating information. A person with a good memory and who knows a lot of facts is not necessarily good at critical thinking. Critical thinkers are able to deduce consequences from what they know, make use of information to solve problems, and to seek relevant sources of information to inform themselves.

Critical thinking should not be confused with being argumentative or being critical of other people. Although critical thinking skills can be used in exposing fallacies and bad reasoning, critical thinking can also play an important role in cooperative reasoning and constructive tasks. Critical thinking can help us acquire knowledge, improve our theories, and strengthen arguments. We can also use critical thinking to enhance work processes and improve social institutions.

Some people believe that critical thinking hinders creativity because critical thinking requires following the rules of logic and rationality, whereas creativity might require breaking those rules. This is a misconception. Critical thinking is quite compatible with thinking “out-of-the-box,” challenging consensus views, and pursuing less popular approaches. If anything, critical thinking is an essential part of creativity because we need critical thinking to evaluate and improve our creative ideas.

II. The I mportance of C ritical T hinking

Critical thinking is a domain-general thinking skill. The ability to think clearly and rationally is important whatever we choose to do. If you work in education, research, finance, management or the legal profession, then critical thinking is obviously important. But critical thinking skills are not restricted to a particular subject area. Being able to think well and solve problems systematically is an asset for any career.

Critical thinking is very important in the new knowledge economy. The global knowledge economy is driven by information and technology. One has to be able to deal with changes quickly and effectively. The new economy places increasing demands on flexible intellectual skills, and the ability to analyze information and integrate diverse sources of knowledge in solving problems. Good critical thinking promotes such thinking skills, and is very important in the fast-changing workplace.

Critical thinking enhances language and presentation skills. Thinking clearly and systematically can improve the way we express our ideas. In learning how to analyze the logical structure of texts, critical thinking also improves comprehension abilities.

Critical thinking promotes creativity. To come up with a creative solution to a problem involves not just having new ideas. It must also be the case that the new ideas being generated are useful and relevant to the task at hand. Critical thinking plays a crucial role in evaluating new ideas, selecting the best ones and modifying them if necessary.

Critical thinking is crucial for self-reflection. In order to live a meaningful life and to structure our lives accordingly, we need to justify and reflect on our values and decisions. Critical thinking provides the tools for this process of self-evaluation.

Good critical thinking is the foundation of science and democracy. Science requires the critical use of reason in experimentation and theory confirmation. The proper functioning of a liberal democracy requires citizens who can think critically about social issues to inform their judgments about proper governance and to overcome biases and prejudice.

Critical thinking is a metacognitive skill . What this means is that it is a higher-level cognitive skill that involves thinking about thinking. We have to be aware of the good principles of reasoning, and be reflective about our own reasoning. In addition, we often need to make a conscious effort to improve ourselves, avoid biases, and maintain objectivity. This is notoriously hard to do. We are all able to think but to think well often requires a long period of training. The mastery of critical thinking is similar to the mastery of many other skills. There are three important components: theory, practice, and attitude.

III. Improv ing O ur T hinking S kills

If we want to think correctly, we need to follow the correct rules of reasoning. Knowledge of theory includes knowledge of these rules. These are the basic principles of critical thinking, such as the laws of logic, and the methods of scientific reasoning, etc.

Also, it would be useful to know something about what not to do if we want to reason correctly. This means we should have some basic knowledge of the mistakes that people make. First, this requires some knowledge of typical fallacies. Second, psychologists have discovered persistent biases and limitations in human reasoning. An awareness of these empirical findings will alert us to potential problems.

However, merely knowing the principles that distinguish good and bad reasoning is not enough. We might study in the classroom about how to swim, and learn about the basic theory, such as the fact that one should not breathe underwater. But unless we can apply such theoretical knowledge through constant practice, we might not actually be able to swim.

Similarly, to be good at critical thinking skills it is necessary to internalize the theoretical principles so that we can actually apply them in daily life. There are at least two ways to do this. One is to perform lots of quality exercises. These exercises don’t just include practicing in the classroom or receiving tutorials; they also include engaging in discussions and debates with other people in our daily lives, where the principles of critical thinking can be applied. The second method is to think more deeply about the principles that we have acquired. In the human mind, memory and understanding are acquired through making connections between ideas.

Good critical thinking skills require more than just knowledge and practice. Persistent practice can bring about improvements only if one has the right kind of motivation and attitude. The following attitudes are not uncommon, but they are obstacles to critical thinking:

- I prefer being given the correct answers rather than figuring them out myself.

- I don’t like to think a lot about my decisions as I rely only on gut feelings.

- I don’t usually review the mistakes I have made.

- I don’t like to be criticized.

To improve our thinking we have to recognize the importance of reflecting on the reasons for belief and action. We should also be willing to engage in debate, break old habits, and deal with linguistic complexities and abstract concepts.

The California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory is a psychological test that is used to measure whether people are disposed to think critically. It measures the seven different thinking habits listed below, and it is useful to ask ourselves to what extent they describe the way we think:

- Truth-Seeking—Do you try to understand how things really are? Are you interested in finding out the truth?

- Open-Mindedness—How receptive are you to new ideas, even when you do not intuitively agree with them? Do you give new concepts a fair hearing?

- Analyticity—Do you try to understand the reasons behind things? Do you act impulsively or do you evaluate the pros and cons of your decisions?

- Systematicity—Are you systematic in your thinking? Do you break down a complex problem into parts?

- Confidence in Reasoning—Do you always defer to other people? How confident are you in your own judgment? Do you have reasons for your confidence? Do you have a way to evaluate your own thinking?

- Inquisitiveness—Are you curious about unfamiliar topics and resolving complicated problems? Will you chase down an answer until you find it?

- Maturity of Judgment—Do you jump to conclusions? Do you try to see things from different perspectives? Do you take other people’s experiences into account?

Finally, as mentioned earlier, psychologists have discovered over the years that human reasoning can be easily affected by a variety of cognitive biases. For example, people tend to be over-confident of their abilities and focus too much on evidence that supports their pre-existing opinions. We should be alert to these biases in our attitudes towards our own thinking.

IV. Defining Critical Thinking

There are many different definitions of critical thinking. Here we list some of the well-known ones. You might notice that they all emphasize the importance of clarity and rationality. Here we will look at some well-known definitions in chronological order.

1) Many people trace the importance of critical thinking in education to the early twentieth-century American philosopher John Dewey. But Dewey did not make very extensive use of the term “critical thinking.” Instead, in his book How We Think (1910), he argued for the importance of what he called “reflective thinking”:

…[when] the ground or basis for a belief is deliberately sought and its adequacy to support the belief examined. This process is called reflective thought; it alone is truly educative in value…

Active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends, constitutes reflective thought.

There is however one passage from How We Think where Dewey explicitly uses the term “critical thinking”:

The essence of critical thinking is suspended judgment; and the essence of this suspense is inquiry to determine the nature of the problem before proceeding to attempts at its solution. This, more than any other thing, transforms mere inference into tested inference, suggested conclusions into proof.

2) The Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (1980) is a well-known psychological test of critical thinking ability. The authors of this test define critical thinking as:

…a composite of attitudes, knowledge and skills. This composite includes: (1) attitudes of inquiry that involve an ability to recognize the existence of problems and an acceptance of the general need for evidence in support of what is asserted to be true; (2) knowledge of the nature of valid inferences, abstractions, and generalizations in which the weight or accuracy of different kinds of evidence are logically determined; and (3) skills in employing and applying the above attitudes and knowledge.

3) A very well-known and influential definition of critical thinking comes from philosopher and professor Robert Ennis in his work “A Taxonomy of Critical Thinking Dispositions and Abilities” (1987):

Critical thinking is reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.

4) The following definition comes from a statement written in 1987 by the philosophers Michael Scriven and Richard Paul for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking (link), an organization promoting critical thinking in the US:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue, assumptions, concepts, empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions, implications and consequences, objections from alternative viewpoints, and frame of reference.

The following excerpt from Peter A. Facione’s “Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction” (1990) is quoted from a report written for the American Philosophical Association:

We understand critical thinking to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, CT is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one’s personal and civic life. While not synonymous with good thinking, CT is a pervasive and self-rectifying human phenomenon. The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fairminded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit. Thus, educating good critical thinkers means working toward this ideal. It combines developing CT skills with nurturing those dispositions which consistently yield useful insights and which are the basis of a rational and democratic society.

V. Two F eatures of C ritical T hinking

A. how not what .

Critical thinking is concerned not with what you believe, but rather how or why you believe it. Most classes, such as those on biology or chemistry, teach you what to believe about a subject matter. In contrast, critical thinking is not particularly interested in what the world is, in fact, like. Rather, critical thinking will teach you how to form beliefs and how to think. It is interested in the type of reasoning you use when you form your beliefs, and concerns itself with whether you have good reasons to believe what you believe. Therefore, this class isn’t a class on the psychology of reasoning, which brings us to the second important feature of critical thinking.

B. Ought N ot Is ( or Normative N ot Descriptive )

There is a difference between normative and descriptive theories. Descriptive theories, such as those provided by physics, provide a picture of how the world factually behaves and operates. In contrast, normative theories, such as those provided by ethics or political philosophy, provide a picture of how the world should be. Rather than ask question such as why something is the way it is, normative theories ask how something should be. In this course, we will be interested in normative theories that govern our thinking and reasoning. Therefore, we will not be interested in how we actually reason, but rather focus on how we ought to reason.

In the introduction to this course we considered a selection task with cards that must be flipped in order to check the validity of a rule. We noted that many people fail to identify all the cards required to check the rule. This is how people do in fact reason (descriptive). We then noted that you must flip over two cards. This is how people ought to reason (normative).

- Section I-IV are taken from http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ and are in use under the creative commons license. Some modifications have been made to the original content. ↵

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Critical Thinking and the Psycho-logic of Race Prejudice. Resource Publication Series 3, No. 1

Related Papers

Mark Weinstein

Harvey Siegel

Educational Theory

Sharon Bailin

Yvonne Wells