A Brief History of Abortion in the U.S.

Abortion wasn’t always a moral, political, and legal tinderbox. What changed?

A bortion laws have never been more contentious in the U.S. Yet for the first century of the country’s existence—and most of human history before that—abortion was a relatively uncontroversial fact of life.

“Abortion has existed for pretty much as long as human beings have existed,” says Joanne Rosen, JD, MA , a senior lecturer in Health Policy and Management who studies the impact of law and policy on access to abortion.

Until the mid-19th century, the U.S. attitude toward abortion was much the same as it had often been elsewhere throughout history: It was a quiet reality, legal until “quickening” (when fetal motion could be felt by the mother). In the eyes of the law, the fetus wasn’t a “separate distinct entity until then,” but rather an extension of the mother, Rosen explains.

What changed?

America’s first anti-abortion movement wasn’t driven primarily by moral or religious concerns like it is today. Instead, abortion’s first major foe in the U.S. was physicians on a mission to regulate medicine.

Until this point, abortion services had been “women’s work.” Most providers were midwives, many of whom made a good living selling abortifacient plants. They relied on methods passed down through generations, from herbal abortifacients and pessaries—a tampon-like device soaked in a solution to induce abortion—to catheter abortions that irritate the womb and force a miscarriage, to a minor surgical procedure called dilation and curettage (D&C), which remains one of the most common methods of terminating an early pregnancy.

The cottage abortion industry caught the attention of the fledgling American Medical Association, which was established in 1847 and, at the time, excluded women and Black people from membership. The AMA was keen to be taken seriously as a gatekeeper of the medical profession, and abortion services made midwives and other irregular practitioners—so-called quacks—an easy target. Their rhetoric was strategic, says Mary Fissell, PhD , the J. Mario Molina professor in the Department of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. “You have to link those midwives to providing abortion as a way of kind of getting them out of business,” Fissell says. “So organized medicine very much takes the anti-abortion position and stays with that for some time.”

Early 19th century and before

Abortion is legal in the U.S. until “quickening”

AMA campaigns to end abortion

At least 40 anti-abortion statutes are enacted in the U.S.

Comstock Act makes it illegal to sell or mail contraceptives or abortifacients

Late 19th century

OB-GYN emerges as a specialty

Griswold v. Connecticut decision finds that the Constitution guarantees a right to privacy, specifically in prescribing contraceptives, paving the way for Roe v. Wade

Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade enshrines abortion as a constitutional right

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey protects a woman's right to have an abortion prior to fetal viability

Four states pass trigger laws making it a felony to perform, procure, or prescribe an abortion if Roe is ever overturned

Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey overturned; 13 states ban abortion by October 2022

In 1857, the AMA took aim at unregulated abortion providers with a letter-writing campaign pushing state lawmakers to ban the practice. To make their case, they asserted that there was a medical consensus that life begins at conception, rather than at quickening.

The campaign succeeded. At least 40 anti-abortion laws went on the books between 1860 and 1880.

And yet some doctors continued to perform abortions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By then, abortion was illegal in almost all states and territories, but during the Depression era, “doctors could see why women wouldn’t want a child,” and many would perform them anyway, Fissell says. In the 1920s and through the 1930s, many cities had physicians who specialized in abortions, and other doctors would refer patients to them “off book.”

That leniency faded with the end of World War II. “All across America, it’s very much about gender roles, and women are supposed to be in the home, having babies,” Fissell says. This shift in the 1940s and ’50s meant that more doctors were prosecuted for performing abortions, which drove the practice underground and into less skilled hands. In the 1950s and 1960s, up to 1.2 million illegal abortions were performed each year in the U.S., according to the Guttmacher Institute . In 1965, 17% of reported deaths attributed to pregnancy and childbirth were associated with illegal abortion.

A rubella outbreak from 1963–1965 moved the dial again, back toward more liberal abortion laws. Catching rubella during pregnancy could cause severe birth defects, leading medical authorities to endorse therapeutic abortions . But these safe, legal abortions remained largely the preserve of the privileged. “Women who are well-to-do have always managed to get abortions, almost always without a penalty,” says Fissell. “But God help her if she was a single, Black, working-class woman.”

Women who could afford it brought their cases to court to fight for access to hospital abortions. Other women gained approval for abortions with proof from a physician that carrying the pregnancy would endanger her life or her physical or mental health. These cases set off a wave of abortion reform bills in state legislatures that helped set the stage for Roe v. Wade . By the time Roe was decided in 1973, legal abortions were already available in 17 states—and not just to save a woman’s life.

But raising the issue to the level of the Supreme Court and enshrining abortion rights for all Americans also galvanized opposition to it and mobilized anti-abortion groups. “ Roe was under attack virtually from the moment it was decided,” says Rosen.

In 1992 another Supreme Court case, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey posed the most significant existential threat to Roe . Rosen calls it “the case that launched a thousand abortion regulations,” upholding Roe but giving states far greater scope to regulate abortion prior to fetal viability. However, defining that nebulous milestone a became a flashpoint for debate as medical advancements saw babies survive earlier and earlier outside the womb. Sonograms became routine around the same time, making fetal life easier to grasp and “putting wind in the sails of the ‘pro-life’ movement,” Rosen says. Then in June, the Supreme Court overturned both Roe and Casey .

For many Americans, that meant the return to the conundrum that led Norma McCorvey—a.k.a. Jane Roe—to the Supreme Court in 1971: being poor and pregnant, and seeking an abortion in a state that had banned them in all but the narrowest of circumstances.

The history of abortion in the U.S. suggests the tides will turn again. “We often see periods of toleration followed by periods of repression,” says Fissell. The current moment is unequivocally marked by the latter. What remains to be seen is how long it will last.

From Public Health On Call Podcast

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

How U.S. abortion laws went from nonexistent to acrimonious

Most scholars say that at the nation's founding ending a pregnancy wasn’t illegal—or even controversial. Here’s a look at the complex early history of abortion in the United States.

There’s no more hot-button issue in the United States than that of abortion. And every time the divisive battle flares up, someone is bound to invoke the historical legacy of abortion in America.

But what is that history? Though interpretations differ, most scholars who have investigated the complex history of abortion argue that terminating a pregnancy wasn’t always illegal—or even controversial. Here’s what they say about the nation’s long, complicated relationship with abortion.

Before abortion law

In colonial America and the early days of the republic, there were no abortion laws at all. Church officials frowned on the practice, writes Oklahoma University of Law legal historian Carla Spivack in the William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice , but they treated the practice as evidence of illicit or premarital sex—not as murder.

Some localities prosecuted cases involving abortions. In 1740s Connecticut, for example, prosecutors tried both a doctor and a Connecticut man for a misdemeanor in connection with the death of Sarah Grosvenor, who had died after a botched abortion. However, the case centered around the men’s role in the woman’s death, not abortion per se, and such prosecutions were rare.

In fact, says Lauren MacIvor Thompson , a historian of women’s rights and public health and an assistant professor at Kennesaw State University, “abortion in the first trimester would have been very, very common.”

That’s in part because of society’s understanding of conception and life.

Many historians agree that in an era long before reliable pregnancy tests, abortion was generally not prosecuted or condemned up to the point of quickening—the point at which a pregnant woman could feel the fetus’ first kicks and movements . At the time quickening might be the only incontrovertible evidence of pregnancy; indeed, one 1841 physician wrote that many women didn’t even calculate their due dates until they had felt the baby kick, which usually takes place during the second trimester, as late as 20 weeks into the pregnancy. That’s when the fetus was generally recognized as a baby or person.

Until the mid-19th century, writes University of Illinois historian Leslie J. Reagan in her book When Abortion Was a Crime, “What we would now identify as an early induced abortion was not called an ‘abortion’ at all. If an early pregnancy ended, it had ‘slipp[ed] away,’ or the menses had been ‘restored.’”

How early abortion worked

At the time, women who did not wish to remain pregnant had plenty of options. Herbs like savin, tansy, and pennyroyal were common in kitchen gardens, and could be concocted and self-administered to, in the parlance of the time, clear “obstructions” or cause menstruation.

“It was really a decision that a woman could choose in private,” MacIvor Thompson says.

A pregnant woman might consult with a midwife, or head to her local drug store for an over-the-counter patent medicine or douching device. If she owned a book like the 1855 Hand-Book of Domestic Medicine , she could have opened it to the section on “emmenagogues,” substances that provoked uterine bleeding. Though the entry did not mention pregnancy or abortion by name, it did reference “promoting the monthly discharge from the uterus.”

Though reasons varied, a lack of reliable contraception, the disgrace of bearing a child outside of marriage, and the dangers of childbirth were the main reasons women terminated their pregnancies. Though birth rates were high—in 1835, the average woman would give birth more than six times during her lifetime—many women wanted to limit the number of times they would have to carry and bear a child. In an era before modern medical procedures, the grave dangers of childbirth were widely understood. In the words of historian Judith Walzer Leavitt, “Women knew that if procreation did not kill them or their babies, it could maim them for life.”

( Women's health concerns are dismissed more, studied less .)

As a result, the deliberation termination of pregnancy was widely practiced, and by some estimates , up to 35 percent of 19th-century pregnancies ended in abortion.

For enslaved women, abortion was more tightly regulated because their children were seen as property. In the Journal of American Studies , historian Liese M. Perrin writes that many slaveholders were paranoid about abortion on their plantations; she documents that at least one slaveholder locked an enslaved woman up and stripped her of privileges because he suspected she had self-induced a miscarriage. Still, bondswomen’s medical care was usually left to Black midwives who practiced folk medicine. And at least some enslaved women are known to have used abortifacients, chewing cotton roots or ingesting substances like calomel or turpentine.

Middle- and upper-class white women, however, had an advantage when it came to detecting and treating unwanted pregnancies in the 19th century. Their strictly defined roles in society held that the home—and issues of reproductive health—were a woman’s realm. And so women, not doctors, were the ones who held and passed down knowledge about pregnancy, childbirth, and reproductive control. “It gave them a space to make their own decisions about their reproductive health,” MacIvor Thompson says.

Criminalizing abortion

That would slowly change throughout the century as the first abortion laws slowly made their ways onto the books. Most were focused on unregulated patent medicines and abortions pursued after quickening. The first , codified in Connecticut in 1821, punished any person who provided or took poison or “other noxious and destructive substance” with the intent to cause “the miscarriage of any woman, then being quick with child.”

Patent medicines were a particular concern; they were available without prescriptions, and their producers could manufacture them with whatever ingredients they wished and advertise them however they liked. Many such medicines were abortifacients and were advertised as such—and they were of particular concern to doctors.

As physicians professionalized in the mid-19th century, they increasingly argued that licensed male doctors, not female midwives, should care for women throughout the reproductive cycle. With that, they began to denounce abortion.

Gynecologist Horatio Storer led the charge. In 1857, just a year after joining the barely decade-old American Medical Association, Storer began pushing the group to explore what he called “criminal abortion.” Storer argued that abortion was immoral and caused “derangement” in women because it interfered with nature. He lobbied for the association to think of abortion not as a medical act, but a grave crime, one that lowered the profession as a whole.

You May Also Like

How an obscure 1944 health law became a focus of U.S. immigration policy

Animal-friendly laws are gaining traction across the U.S.

How did this female pharaoh survive being erased from history?

A power player within the association, he gathered fellow physicians into a crusade called the Physicians Campaign Against Abortion. The doctors’ public stance helped serve as justification for an increasing number of criminal statutes.

For its opponents, abortion was as much a social evil as a moral one. The influx of immigrants, the growth of cities, and the end of slavery prompted nativist fears that white Americans were not having enough babies to stave off the dominance of groups they found undesirable. This prompted physicians like Storer to argue that white women should have babies for the “future destiny of the nation.”

A nation of outlaws

By 1900, writes University of Oregon historian James C. Mohr in his book Abortion in America , “the United States completed its transition from a nation without abortion laws of any sort to a nation where abortion was legally and officially proscribed.” Just 10 years later, every state in the nation had anti-abortion laws—although many of these laws included exceptions for pregnancies that endangered the life of the mother.

With the help of a U.S. postal inspector named Anthony Comstock, it had also become harder to access once-common information on how to end an unwanted pregnancy. The 1873 Comstock Act made it illegal to send “obscene” materials—including information about abortion or contraception—through the mail or across state lines.

“Americans understood that abortion and birth control went hand in hand,” MacIvor Thompson says.

The combination of anti-obscenity laws, criminal statutes, and the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act , which made it unlawful to make, sell, or transport misbranded or “deleterious” drugs or medicines, made it increasingly difficult for women to access safer forms of abortion.

“The legal punishments in place absolutely had a chilling effect,” says MacIvor Thompson. “And yet, just like a hundred years earlier, women still sought them frequently.”

As the 20th century dawned, under-the-table surgical abortions became more common, discreetly practiced by physicians who advertised by word-of-mouth to those who could afford their services. Those who could not used old herbal recipes, drank creative concoctions, douched with substances like Lysol, or attempted to remove the fetuses on their own.

Advocates of the growing birth control movement even used now-illegal abortion to argue for legal contraception. Birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger said that she was inspired to make teaching women about contraceptives her career after treating a woman who died from a self-induced abortion—a practice she called a “disgrace to a civilized community.”

( How the first birth control pill was designed .)

It’s still up for debate how frequently women sought abortions in the 20th century—and how often they died from self-induced or botched, “back-alley” abortions. In 1942, the question vexed the Bureau of the Census’ chief statistician, Halbert Dunn, who noted that, despite the lack of accurate reporting, “abortion is evidently still one of the greatest problems to be met in lowering further the maternal mortality rate for the country.”

The modern battle over abortion

By 1967, abortion was a felony in nearly every state, with few provisions for the health of the mother or pregnancies arising from rape.

But all that changed in the 1970s. States across the country had begun to reconsider their laws and loosen their restrictions on abortion, and in 1973, the Supreme Court seemingly settled the question with two landmark rulings— Roe v. Wade and the lesser-known but equally important Doe v. Bolton— that made terminating a pregnancy a legal right nationwide.

( The tumultuous history that led to the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling. )

The country has debated the merits of those rulings ever since. In June 2022, the Supreme Court made the momentous decision to overturn Roe . Now, generations of women who have never known life before Roe face yet another shift in the landscape of the nation’s contentious history of abortion.

Related Topics

- SEXUAL HEALTH

- LAW AND LEGISLATION

Naked mole rats are fertile until they die. Here’s how that can help us.

Title IX at 50: How the U.S. law transformed education for women

How COVID-19 can harm pregnancy and reproductive health

Birth control options for men are advancing. Here’s how they work.

Could menopause be delayed? The answer could lead to longer lifespans for women

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

A brief history of abortion – from ancient Egyptian herbs to fighting stigma today

PhD Candidate in English Literature, The University of Edinburgh

Disclosure statement

Alisha Palmer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The University of Edinburgh provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

You might be forgiven for thinking of abortion as a particularly modern phenomenon. But there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that abortion has been a constant feature of social life for thousands of years . The history of abortion is often told as a legal one, yet abortion has continued regardless of, perhaps even in spite of, legal regulation.

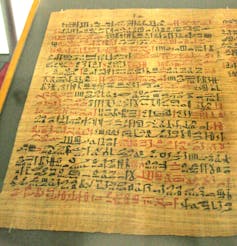

The need to regulate fertility before or after sex has existed for as long as pregnancy has. The Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Ebers is often seen as some of the first written evidence of abortion practice.

Dating back to 1600BC, the text describes methods by which “the woman empties out the conceived in the first, second or third time period”, recommending herbs, vaginal douches and suppositories. Similar methods of inducing abortion were recorded , although not recommended, by Hippocrates around the fourth century BC.

Part of the daily life of ancient citizens, abortion also found its way into their art. Publius Ovidius Naso, commonly known as Ovid, was a Roman poet whose collection of works Amores describes the narrator’s emotional turmoil as he watches his lover suffering from a mismanaged abortion:

While she rashly is overthrowing the burden of her pregnant womb, weary Corinna lies in danger of her life. Having attempted so great a danger without telling me. She deserves my anger, but my anger dies with fear.

Ovid’s concern at first is with the risk of losing his love Corinna, not the potential child. Later, he asks the gods to ignore the “destruction” of the child and save Corinna’s life. This reveals some important aspects of historical attitudes towards abortion.

This article is part of Women’s Health Matters , a series about the health and wellbeing of women and girls around the world. From menopause to miscarriage, pleasure to pain the articles in this series will delve into the full spectrum of women’s health issues to provide valuable information, insights and resources for women of all ages.

You may be interested in:

Five old contraception methods that show why the pill was a medical breakthrough

The orgasm gap and why women climax less than men

Science experiments traditionally only used male mice – here’s why that’s a problem for women’s health

While 21st-century abortion debates often revolve around questions of life and personhood, this was not always the case. The Ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, did not necessarily believe that a foetus was alive.

Early thinkers such as St. Augustine (AD354-AD430), for example, distinguished between the embryo “informatus” (unformed) and “formatus” (formed and endowed with a soul). Over time, the most common distinction became drawn at what was known as the “quickening” , which was when the pregnant woman could feel the baby move for the first time. This determined that the foetus was alive (or had a soul).

As a delayed period was often the first sign something was amiss, and a woman may not have considered herself pregnant until much later, a lot of advice on abortion would focus on restoring menstrual irregularities or blockages instead of terminating a potential pregnancy (or foetus).

As a result, much of the abortion advice throughout history does not necessarily mention abortion at all. And it was often down to personal interpretation whether or not an abortion had even taken place.

Indeed, recipes for “abortifacients” (any substance that is used to terminate a pregnancy) could be found in medical texts like those from the German nun Hildegard von Bingen in 1150 and in domestic recipe books with treatments for other common ailments well into the 20th century.

In the west, the quickening distinction gradually went out of fashion over the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet women continued to have abortions despite changing beliefs about life and the law. In fact, some sources claimed, they seemed to be more common than ever.

“An epidemic of abortions”

In 1920, Russia became the first state in the world to legalise abortion, and in 1929, famous birth control advocate Marie Stopes lamented that “an epidemic of abortions” was sweeping England. Similar claims from France and the US also indicate a perceived uptick.

These claims accompanied a wave of plays, poems and novels that included abortion. In fact, in 1923, Floyd Dell, the US magazine editor and writer, published a new work of fiction, Janet March , where the main character complains about the number of novels that feature abortions, stating there “were dreadful things enough in novels, but they happened only to poor girls – ignorant and reckless girls”.

But the literature of the early 20th century, with many stories based on women’s real experiences, attests to a wider range of abortions than the stereotypical image of the poor and destitute backstreet operations of the 1900s.

For example, the English novelist, Rosamond Lehmann records a seductive “feminine conspiracy” of aborting women waiting with “tact, sympathy, pills and hot-water bottles”, in her 1926 novel The Weather in the Streets .

These texts form part of a long tradition of abortion storytelling that is a predecessor to contemporary activism. For example, We Testify is an organisation dedicated to the leadership and representation of people who have abortions. And Shout Your Abortion is a social media campaign where people share their abortion experiences online without “sadness, shame or regret”.

Abortion has a long and varied history, but above all these texts – from the Egyptian papyri of 1600BC to the social media posts of today – show that abortion has been and remains central to our history, our lives and even our art.

- Abortion law

- Women's health series

- Women's Health Matters

Research Fellow Community & Consumer Engaged Health Professions Education

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Exploring the complicated history of abortion in the United States

John Yang John Yang

Lorna Baldwin Lorna Baldwin

Maea Lenei Buhre Maea Lenei Buhre

Sam Lane Sam Lane

Layla Quran Layla Quran

Sam Weber Sam Weber

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/exploring-the-complicated-history-of-abortion-in-the-united-states

In the leaked Supreme Court draft opinion striking down Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito writes that the nation has had an “unbroken tradition” of criminalizing abortion. But as John Yang reports, the history is much more complicated.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

In the leaked Supreme Court draft opinion striking down Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito writes that the nation has a — quote — "unbroken tradition" of criminalizing abortion.

But, as John Yang reports, the history is actually much more complicated.

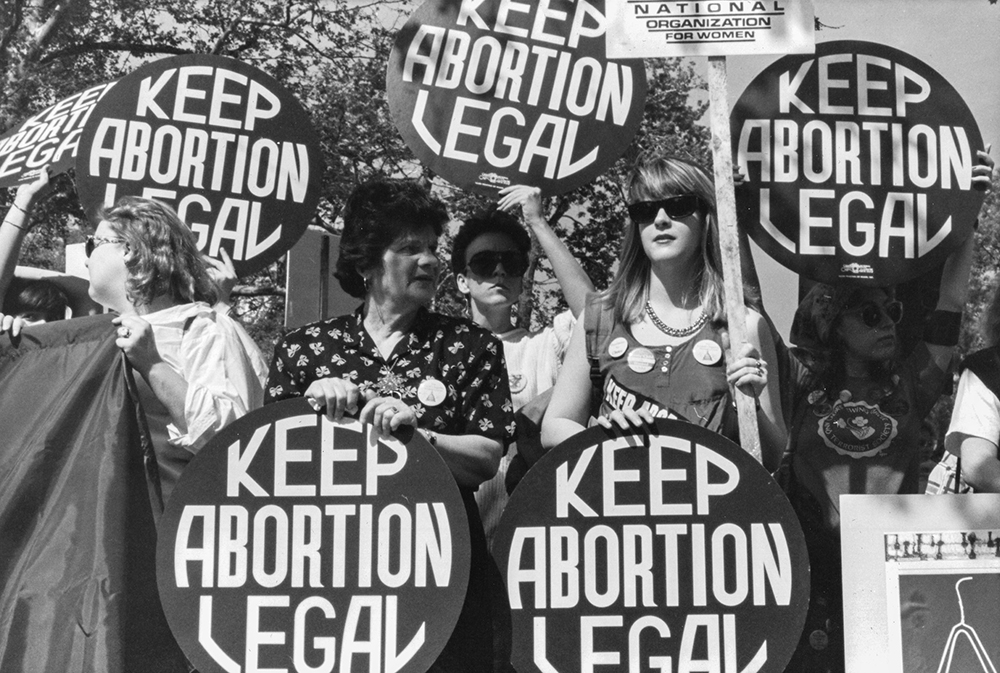

For almost a half-century, scenes like this have become nearly routine outside women's health clinics around the country.

Protesters:

Stop murdering your baby. Please, let us help you.

Roe v. Wade has got to go, hey, hey, ho, ho!

In the nation's capital, supporters on each side of the abortion divide made their voices heard.

Pro-family! Pro-choice!

But in the country's earliest years, abortion was not against the law.

Michele Goodwin, Author, "Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood": Indigenous people had been performing all manner of health care, abortions, helping people carry pregnancies to terms. The Pilgrims were performing abortions.

Michele Goodwin is a law professor at the University of California, Irvine.

Michele Goodwin:

Abortion becomes a controversial issue that is ripe then for legislative debate close to the time of the Civil War.

And it's at a time in which males are getting involved in reproduction. Prior to that time, nearly 100 percent of women's reproductive health care had all been done by women and had been done by midwives.

Midwives who helped deliver babies also helped women terminate pregnancies.

Jennifer Holland is a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma.

Jennifer Holland, University of Oklahoma: And in English common law, abortions were illegal before something called quickening, which is when woman felt a fetus move, somewhere between the fourth and sixth month of pregnancy.

And all abortions before that were legal. And only after that were they illegal.

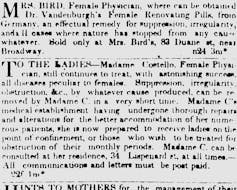

Women could find ways to terminate pregnancies in the pages of their newspapers. Ads promoted products with shrewdly disguised names like Dr. Vandenburgh's Female Renovating Pills or services like those Madame Costello provided for ladies "who wish to be treated for obstruction of their monthly periods."

In New York, Madame Restell was considered a heroine to her patients, but demonized in the press, labeled "The Abortionist of Fifth Avenue." Her business success spawned copycats in other cities.

In 1847, a group of white men formed the American Medical Association. They pushed for laws to make abortion illegal in an effort to put midwives like Madame Restell out of business. The effort to outlaw abortion was also driven by a growing fear of foreign nonwhite immigration and declining birth rates among white Protestants.

It was deeply racial, tying into the fact that the nation was soon to be at war and that there were tensions that were already building, with abolitionists saying, these are horrible things that we see taking place in the antebellum South.

And so they connected a racist impact to that too, saying that white women needed to use their loins and go north, south, east and west because of the potential browning of America.

Between the end of the Civil War in 1910, abortion was banned in all the states, except in cases where either the life of the mother or the viability of the fetus was at risk. But abortion was still practice in secret.

Late 19th century observers estimated that, each year, there were two million abortions. And, in 1930, one-fifth of recorded maternal deaths were from these unsafe illegal procedures often called back alley abortions. They have been portrayed in popular culture, here in the film "Dirty Dancing," which was set in 1963.

He didn't use no ether, nothing.

Jennifer Grey, Actress:

I thought you said he was a M.D.

The guy had dirty knife and a folding table. I could hear her screaming in the hallway. And I swear to God, Johnny, I tried to get in. I tried.

Attitudes toward abortion began to shift in the 1960s. One example, the highly publicized case of Sherri Chessen Finkbine, the host of a popular children's TV show.

She feared her developing fetus was damaged as a result of taking thalidomide for morning sickness. She went to Sweden for an abortion because it was illegal in the United States. At the time, a Gallup poll showed 52 percent of Americans said she did the right thing.

Jennifer Holland:

In the mid-'60s, you have this reform movement grow up. And clergy were really outspoken in this particular reform movement. And it's this group of clergy from all different denominations, Jewish, Protestant. And they counseled women about abortion, and helped them seek abortions, and not only that, but then the clergy would testify about their actions in the state legislatures. So they were openly breaking the law.

Another group based in Chicago, the Jane Collective, worked underground to help thousands of women obtain abortions between 1969 and 1973.

The push for abortion rights also became more visible, and pressure was on to liberalize abortion laws.

We're here because we were not allowed to testify to this all-male committee who's deciding what should happen to our bodies and our lives.

Hawaii, New York, Alaska and Washington state were the first to legalize abortion access for women in 1970. Then, in January 1973, the Supreme Court announced its landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, legalizing abortion nationwide.

These are justices that are looking at the American landscape and finding that abortions have not stopped. There are people who are discovering women in motel rooms dying or dead on top of sheets and towels, women being found on kitchen tables having tried to self-manage an abortion because it's been made criminalized.

The Roe v. Wade ruling fueled a movement against abortion. Groups staged marches and sit-ins across the country in protest.

Catholics and evangelicals and also Mormons, they fundamentally disagreed, not only disagreed about theology, but believed they — each of them believed that they had the monopoly on religious truth.

But they really are able to link themselves through abortion politics, and saying that they are linked by something called Judeo-Christian values, which the anti-abortion movement resuscitates as an idea in the '70s to sort of cover this idea that all Christians, of course, oppose abortion, and they always have. And, of course, that was a manufactured idea of this movement, because religious people had been very openly supporting abortion, and very recently.

And they knew that wasn't true. In the late '70s, '80s and '90s, you have Republicans acknowledge the power of this voting base. The movement has been incredibly good at developing a constituency for whom no other issue matters. Not any other issue matters as much as this issue.

In those same decades, some took their beliefs to an extreme, using violence, including bombings, arsons, and even murders of abortion providers.

That is a real threat that continues to exist, not on the scale that it was, though, in the 1980s.

This is now a political movement, and not just something that is simply in the streets. There is a kind of political movement that has taken, that has galvanized, picked up steam, and been able to win victories both at the state legislative level and also in American courts.

I think both Donald Trump and these very fervent state legislatures — legislators who believe very deeply on this issue are really a product of the power of this movement.

It's an issue that's become one of the most divisive of the day.

Outside the Supreme Court, protests continue, as the country awaits the court's final decision.

For the "PBS NewsHour," I'm John Yang.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

John Yang is the anchor of PBS News Weekend and a correspondent for the PBS News Hour. He covered the first year of the Trump administration and is currently reporting on major national issues from Washington, DC, and across the country.

Lorna Baldwin is an Emmy and Peabody award winning producer at the PBS NewsHour. In her two decades at the NewsHour, Baldwin has crisscrossed the US reporting on issues ranging from the water crisis in Flint, Michigan to tsunami preparedness in the Pacific Northwest to the politics of poverty on the campaign trail in North Carolina. Farther afield, Baldwin reported on the problem of sea turtle nest poaching in Costa Rica, the distinctive architecture of Rotterdam, the Netherlands and world renowned landscape artist, Piet Oudolf.

Maea Lenei Buhre is a general assignment producer for the PBS NewsHour.

Sam Lane is reporter/producer in PBS NewsHour's segment unit.

Layla Quran is a general assignment producer for PBS NewsHour. She was previously a foreign affairs reporter and producer.

Sam Weber has covered everything from living on minimum wage to consumer finance as a shooter/producer for PBS NewsHour Weekend. Prior joining NH Weekend, he previously worked for Need to Know on PBS and in public radio. He’s an avid cyclist and Chicago Bulls fan.

Support Provided By: Learn more

More Ways to Watch

Educate your inbox.

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Abortion rights:...

Abortion rights: history offers a blueprint for how pro-choice campaigners might usefully respond

- Related content

- Peer review

- Agnes Arnold Forster , research fellow

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

In October 1971, the New York Times reported a decline in maternal death rate. 1 Just 15 months earlier, the state had liberalised its abortion law. David Harris, New York’s deputy commissioner of health, speaking to the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, attributed the decline—by more than half—to the replacement of criminal abortions with safe, legal ones. Previously, abortion had been the single leading cause of maternity related deaths, accounting for around a third. A doctor in the audience who said he was from a state “where the abortion law is still archaic,” thanked New York for its “remarkable job” and expressed his gratitude that there was a place he could send his patients and know they would receive “safe, excellent care.” Harris urged other states to follow the example set by New York and liberalise their abortion laws.

Just two years later, in 1973, the US Supreme Court intervened. In the landmark decision, Roe v. Wade, the Court ruled that the constitution protected a woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion, and in doing so, struck down the “archaic” abortion laws that still existed in many states.

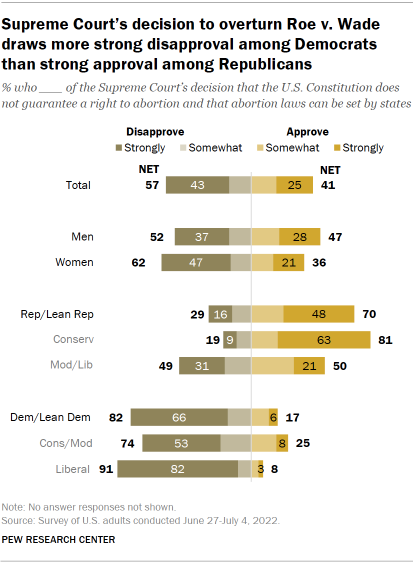

As surely everyone knows by now, Roe v. Wade was repealed on 24 June 2022, setting off a wave of fear, uncertainty, rage, and apprehension among those committed to the right to choose. Thirteen states with “trigger bans,” designed to take effect automatically if the ruling was ever struck down, are due to prohibit abortion within 30 days. 2 At least eight states banned the procedure the day the ruling was released. Several others are expected to act, with lawmakers moving to reactivate their dormant legislation. But as the 1971 New York Times article indicates, banning abortion only bans safe abortion.

In November 1955, Jacqueline Smith found out she was about six weeks pregnant. Historian Gillian Frank describes what happened next. 3 Unmarried and anxious about the social consequences for mothers and babies born out of wedlock, Jacqueline and her boyfriend Daniel started looking for methods to end the pregnancy. On the 24 December 1955, Daniel paid a hospital attendant, $50 to perform an illegal abortion in the living room of the boyfriend’s Manhattan apartment. Just a few hours later, Jacqueline was dead. Before abortion was legalised in Great Britain in 1967, the situation on this side of the Atlantic was similar.

As the New York Times article suggests, these names were just some of thousands of women who lost their lives to backstreet abortions or forced birth, and of many more who had their lives irreparably altered by being made to carry babies to term that they were not able to care for or that they simply did not want. But if history foreshadows a terrifying history for women in America, it also offers a blueprint for how pro-choice campaigners might usefully respond.

Roe v. Wade was a landmark legal decision, but it came only after decades of grassroots feminist activism. In early 1960s California, radical activist Pat Maginnis taught women how to fake the symptoms that would get them a “therapeutic abortion” (then the only legal kind). 4 She founded a group called the Society for Humane Abortion that demanded the repeal of abortion laws and ran an underground network focused on helping women obtain safe abortions, compiling lists of abortion providers outside the US, and providing women with tips on how to evade suspicion at the Mexican border. While some doctors and others were advocating reformed abortion laws in the first half of the twentieth century, it was feminists like Maginnis who were the first to publicly insist that abortion should be completely decriminalised. In 1969, the radical feminist group Redstockings organised an “abortion speakout” in New York City, where women talked about their experiences with illegal terminations. This history shows that women have always been at the forefront of pro-choice activism, and sadly will have to be once again.

But abortion rights also need to be protected closer to home. While abortion is legal in Northern Ireland, millions of women, girls, and people remain without access and must travel to England to receive appropriate reproductive care. Similarly, due to the legacy of nineteenth-century legislation, abortion remains a criminal offence in England—and doctors must lend their substantial social and political capital to the campaign to overturn the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. 5

The world is radically different to how it was in the 1960s. But two things remain constant. Reproductive rights are fundamental to women’s health, safety, and autonomy. And if access to abortion is to be reinstated or expanded in both the United Kingdom and the United States, then healthcare professionals need to be led by, and work in collaboration with, feminist activists.

Competing interests: AA-F’s research is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Provenance and peer review: commissioned, not peer reviewed.

- ↵ The New York Times. Decline in Maternal Death Rate Linked to Liberalized Abortion. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/10/13/archives/decline-in-maternal-death-rate-linked-to-liberalized-abortion.html?searchResultPosition=1

- ↵ NPR. 'Trigger laws' have been taking effect now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned. https://www.npr.org/2022/06/24/1107531644/trigger-laws-have-been-taking-effect-now-that-roe-v-wade-has-been-overturned

- ↵ Slate. The Death of Jacqueline Smith. https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/12/jacqueline-smiths-1955-death-and-the-lessons-we-havent-yet-learned-from-it.html

- ↵ NPR. Inside Pat Maginnis' radical (and underground) tactics on abortion rights in the '60s. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/29/1047068724/pat-was-an-early-radical-abortion-rights-activist-her-positions-are-now-common

- ↵ Freeman H. The Guardian. Abortion should be a medical matter, not a criminal one. The law needs to change. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/01/uk-abortion-criminal-offence-24-week-time-limit

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Roe v. Wade

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 21, 2023 | Original: March 27, 2018

Roe v. Wade was a landmark legal decision issued on January 22, 1973, in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Texas statute banning abortion, effectively legalizing the procedure across the United States. The court held that a woman’s right to an abortion was implicit in the right to privacy protected by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution . Prior to Roe v. Wade , abortion had been illegal throughout much of the country since the late 19th century. Since the 1973 ruling, many states imposed restrictions on abortion rights. The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on June 24, 2022, holding that there was no longer a federal constitutional right to an abortion.

Abortion Before Roe v. Wade

Until the late 19th century, abortion was legal in the United States before “quickening,” the point at which a woman could first feel movements of the fetus, typically around the fourth month of pregnancy.

Some of the early regulations related to abortion were enacted in the 1820s and 1830s and dealt with the sale of dangerous drugs that women used to induce abortions. Despite these regulations and the fact that the drugs sometimes proved fatal to women, they continued to be advertised and sold.

In the late 1850s, the newly established American Medical Association began calling for the criminalization of abortion, partly in an effort to eliminate doctors’ competitors such as midwives and homeopaths.

Additionally, some nativists, alarmed by the country’s growing population of immigrants, were anti-abortion because they feared declining birth rates among white, American-born, Protestant women.

In 1869, the Catholic Church banned abortion at any stage of pregnancy, while in 1873, Congress passed the Comstock law, which made it illegal to distribute contraceptives and abortion-inducing drugs through the U.S. mail. By the 1880s, abortion was outlawed across most of the country.

During the 1960s, during the women’s rights movement, court cases involving contraceptives laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade .

In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a law banning the distribution of birth control to married couples, ruling that the law violated their implied right to privacy under the U.S. Constitution . And in 1972, the Supreme Court struck down a law prohibiting the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried adults.

Meanwhile, in 1970, Hawaii became the first state to legalize abortion, although the law only applied to the state’s residents. That same year, New York legalized abortion, with no residency requirement. By the time of Roe v. Wade in 1973, abortion was also legally available in Alaska and Washington .

In 1969, Norma McCorvey, a Texas woman in her early 20s, sought to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. McCorvey, who had grown up in difficult, impoverished circumstances, previously had given birth twice and given up both children for adoption. At the time of McCorvey’s pregnancy in 1969 abortion was legal in Texas—but only for the purpose of saving a woman’s life.

While American women with the financial means could obtain abortions by traveling to other countries where the procedure was safe and legal, or pay a large fee to a U.S. doctor willing to secretly perform an abortion, those options were out of reach to McCorvey and many other women.

As a result, some women resorted to illegal, dangerous, “back-alley” abortions or self-induced abortions. In the 1950s and 1960s, the estimated number of illegal abortions in the United States ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

After trying unsuccessfully to get an illegal abortion, McCorvey was referred to Texas attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington, who were interested in challenging anti-abortion laws.

In court documents, McCorvey became known as “Jane Roe.”

In 1970, the attorneys filed a lawsuit on behalf of McCorvey and all the other women “who were or might become pregnant and want to consider all options,” against Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County, where McCorvey lived.

Earlier, in 1964, Wade was in the national spotlight when he prosecuted Jack Ruby , who killed Lee Harvey Oswald , the alleged assassin of President John F. Kennedy .

Supreme Court Ruling

In June 1970, a Texas district court ruled that the state’s abortion ban was illegal because it violated a constitutional right to privacy. Afterward, Wade declared he’d continue to prosecute doctors who performed abortions.

The case eventually was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile, McCovey gave birth and put the child up for adoption.

On Jan 22, 1973, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, struck down the Texas law banning abortion, effectively legalizing the procedure nationwide. In a majority opinion written by Justice Harry Blackmun , the court declared that a woman’s right to an abortion was implicit in the right to privacy protected by the 14th Amendment .

The court divided pregnancy into three trimesters, and declared that the choice to end a pregnancy in the first trimester was solely up to the woman. In the second trimester, the government could regulate abortion, although not ban it, in order to protect the mother’s health.

In the third trimester, the state could prohibit abortion to protect a fetus that could survive on its own outside the womb, except when a woman’s health was in danger.

5 Historic Supreme Court Rulings Based on the 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment's guarantee to "due process" provided a basis for these five Supreme Court rulings that have impacted Americans' lives.

Reproductive Rights in the US: Timeline

Since the early 1800s, U.S. federal and state governments have taken steps both securing and limiting access to contraception and abortion.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Landmark Opinions on Women’s Rights

The Supreme Court Justice was the second woman to hold the role—and battled gender discrimination since the 1970s.

Legacy of Roe v. Wade

Norma McCorvey maintained a low profile following the court’s decision, but in the 1980s she was active in the abortion rights movement.

However, in the mid-1990s, after becoming friends with the head of an anti-abortion group and converting to Catholicism, she turned into a vocal opponent of the procedure.

Since Roe v. Wade , many states imposed restrictions that weaken abortion rights, and Americans remain divided over support for a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

In 1992, litigation against Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act reached the Supreme Court in a case called Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey . The court upheld the central ruling in Roe v. Wade but allowed states to pass more abortion restrictions as long as they did not pose an “undue burden."

Roe v. Wade Overturned

In 2022, the nation's highest court deliberated on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization , which regarded the constitutionality of a Mississippi law banning most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Lower courts had ruled the law was unconstitutional under Roe v. Wade . Under Roe , states had been prohibited from banning abortions before around 23 weeks—when a fetus is considered able to survive outside a woman's womb.

In its decision , the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of Mississippi's law—and overturned Roe after its nearly 50 years as precedent.

Abortion in American History. The Atlantic . High Court Rules Abortion Legal in First 3 Months. The New York Times . Norma McCorvey. The Washington Post . Sarah Weddington. Time . When Abortion Was a Crime , Leslie J. Reagan. University of California Press .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Social Media

- Facebook Facebook Circle Icon

- Twitter Twitter Circle Icon

- Flipboard Flipboard Circle Icon

- RSS RSS Circle Icon

- Culture & Media

- Economy & Labor

- Education & Youth

- Environment & Health

- Human Rights

- Immigration

- LGBTQ Rights

- Politics & Elections

- Prisons & Policing

- Racial Justice

- Reproductive Rights

- War & Peace

- Series & Podcasts

- Climate Crisis

- 2024 Election

UNRWA: Israel Denying Visas to Aid Groups, “Phasing Out” Humanitarians in Gaza

Vance explains trump’s “concept of a plan” is to essentially dismantle obamacare, israel is carrying out deliberate “starvation campaign” in gaza, says un expert, postal workers plan day of action to fight dejoy’s plan to “modernize” the usps, abortion is as old as pregnancy: 4,000 years of reproductive rights history.

On Roe v. Wade’s 43rd anniversary, a look at abortion history offers perspective on the current era of decreased access.

Abortion has always existed. The earliest written record of abortion is more than 4,000 years old. Pregnancy has always been accompanied by the seeking and sharing of methods for ending pregnancy.

The United States’ history with abortion is complicated and currently in flux. Up until 1821, abortion simply existed and, like pregnancy and other “woman-related” business, was entrusted to midwives and other caregivers. The transition to outright criminalization of abortion would take more than 50 years; prohibition would last a century.

Because Roe v. Wade – which turns 43 today – decriminalized abortion through a right to privacy framework, states have been allowed to enact some restrictions on later-term abortions since 1973. We are in yet another new era – one of decreased access to safe, legal abortion care, which has sparked a collaborative effort of grassroots activists and large, national organizations to reverse this dangerous trend.

Abortion in Times of Old

Instructions for inducing an abortion appear in the Bible. In Numbers 5:11-31 , God is described as instructing Moses to present “The Test for an Unfaithful Wife” (NIV) – a ritual to be used by priests against women accused by their husbands of unfaithfulness. The ritual involves the drinking of “bitter water,” a potion that will abort any pregnancies that result from “having sexual relations with a man other than your husband.”

Rickie Solinger, historian and author of Reproductive Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know and What Is Reproductive Justice? , which will be published next year, described the scope of methods used over time to Truthout.

“In Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance , John Riddle showed, through extraordinary scholarly sleuthing, that women from ancient Egyptian times to the 15th century had relied on an extensive pharmacopoeia of herbal abortifacients and contraceptives to regulate fertility,” Solinger said.

The comprehensive timeline from 4000 Years for Choice , an organization which celebrates the reproductive roots of abortion and contraception through art and education, tracks abortion all the way back to the 3000s BCE, referencing the Royal Archives of China, which holds the earliest written record of an abortion technique.

“Women always have and always will have abortions,” Heather Ault , 4000 Years for Choice founder and graphic designer, told Truthout. “It’s fundamental to human existence, and all human societies around the world have practiced forms of controlling pregnancy, to various degrees of effectiveness with the tools and knowledge they had available at that time, whether it be toxic herbs, early surgical methods or magic and spells.”

Ault’s US timeline picks up in the 1600s when enslaved African women were using the cottonwood plant to abort fetuses in a moment when many pregnancies were the result of rape by slave owners, and colonial women used “the savin from the juniper bush, pennyroyal, tansy, ergot, and seneca snakeroot to abort pregnancies.” Until the early 1800s, abortion was legal through common law before “ quickening ,” when the baby’s first detectable motion in the womb indicated it was alive (approximately the fourth month). After quickening, inducing a miscarriage was a common law misdemeanor.

In 1821, however, Connecticut passed the country’s first abortion restriction to make using “poison” after quickening a crime punishable by life in prison. (The sentence would later be reduced to 10 years.) Several states followed suit and by the end of the 19th century, every state except Kentucky – which waited until 1910 – had passed anti-abortion legislation. The American Medical Association, which formed in 1857 and immediately set out to make all abortion illegal , provided legitimacy to the incremental infringement on bodily autonomy.

Then, the politician and “morality” advocate Anthony Comstock began his crusade against birth control, sex workers and eventually abortion. In 1873, the “Comstock Law” outlawed contraception and abortion with limited exceptions for health. With the passage of this law, women lost what had been their common law right.

“Anthony Comstock was the main anti-choice person who, in the late 1800s, starting burning books and made it illegal for anything to be sent through the mail having to do with sexuality,” Ault said. “He later jailed Margaret Sanger [for defying the contraception prohibition] and was on her case until he died.”

By the late 1920s, some 15,000 women a year died from abortions because safe, legal procedures were nearly impossible for most to obtain. According to 4000 Years for Choice, dangerous self-induction methods included using knitting needles, crochet hooks, hairpins, scissors and buttonhooks. With the death toll rising, physicians in the 1930s began providing abortion care through underground clinics and in subsequent decades individuals and doctors banded together to work around and protest the prohibition.

According to David Grimes , former chief of the Abortion Surveillance Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the 1950s, approximately 200,000 to 1.2 million illegal, unsafe abortions were performed per year.

The horror stories of the pre- Roe back-alley days are well documented. Brave people have increasingly been telling their stories as they’ve watched the flurry of anti-abortion laws passing in states across the country bring back flashes of the bad old days. Their words bring the mortality statistics of the abortion prohibition days into stark focus, but our elected officials have largely brushed them aside.

Abortion After Roe v. Wade

Finally, after 100 years without access to safe, legal abortion in the United States, Dallas area resident Norma L. McCorvey’s (“Jane Roe”) case claiming a Texas law criminalizing most abortions violated her constitutional rights arrived at the Supreme Court . On January 22, 1973, the court’s 7-2 decision found that the Texas law violated four separate constitutional amendments and declared an individual’s “zone of privacy” extended to their doctor’s office, thus lifting the ban on abortion. Justice Harry Blackmun’s decision stated that more narrow state laws could be constitutional after the point of viability for the fetus; this, unfortunately, has allowed the onslaught of state-level restrictions that has intensified since 2011.

The United Nations may have declared that “unnecessary restrictions on abortion should be removed and governments should provide access to safe abortion services,” but US legislators seem not to have gotten the message. The Guttmacher Institute, a sexual and reproductive health and rights research and education group, reports that in just the past four years, 231 abortion restrictions have been enacted at the state level. The Population Institute ’s latest “ 50 State Report Card ” grades the US overall at a D+ in overall reproductive rights and health – a slip from 2014’s C rating. Guttmacher now ranks 27 states as either “hostile” or “extremely hostile” to abortion.

While 17 states have introduced 95 measures designed to expand access to abortion – more positive measures than in any year since 1990 – these laws aren’t passing at a rate that rivals the effectiveness of the anti-abortion movement and its legislators. As Heather D. Boonstra, Guttmacher Institute’s director of public policy, wrote at The Hill , “for many women in the United States, safe and legal abortion has long been out of reach.”

This year, reproductive rights and justice groups as well as grassroots activists are pushing for new legislation – like Rep. Barbara Lee’s (D-California) Equal Access to Abortion Coverage in Health Insurance Act – to “ Reclaim Roe ” and begin reversing the trend of restrictions that disproportionately affect the poor and communities of color.

Reclaiming Roe

The real test for whether Roe is reclaimable comes this March when the Supreme Court hears its first abortion case in eight years: Whole Woman’s Health v. Cole , a case concerning a Texas law designed to close down more than 75 percent of clinics that provide abortion services in the state, which was made famous by the filibuster in the Texas Capitol in 2013. The law has been described by many opponents as a de facto abortion ban.

With a historic set of 45 amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court, including expert legal, legislative and medical opinions as well as the abortion stories of a wide variety of people – attorneys, legislators, stay-at-home parents, immigrants, undocumented people and youth – the justices will have all the data ahead of arguments on March 2 . This decision will determine whether reducing abortion clinic numbers into single digits for a state the size of Texas constitutes an “undue burden,” and will possibly set new precedent for the country.

“The Supreme Court has never wavered in affirming that every woman has a right to safely and legally end a pregnancy in the US – and this extreme abortion ban was a direct affront to that right,” said Nancy Northup, president and CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights. “We now look to the justices to ensure Texas women are not robbed of their health, dignity and rights under false pretenses and strike down the state’s deceptive clinic shutdown law currently under review.”

Urgent! We have a limited amount of time

Truthout has launched a crucial fundraising campaign to support our work. We have 9 days to raise $50,000.

Every single day, our team is reporting deeply on complex political issues: revealing wrongdoing in our so-called justice system, tracking global attacks on human rights, unmasking the money behind right-wing movements, and more. Your donation at this moment is critical, allowing us to do this core journalistic work.

Help safeguard what’s left of our democracy. Please make a tax-deductible gift before time runs out.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

From Commonplace to Controversial: The Different Histories of Abortion in Europe and the United States

- Anna M. Peterson

Planned Parenthood supporters demonstrate in Columbus, Ohio, 2012. Over the last hundred years abortion practices and policies have gone in very different directions in Western Europe and the United States, where abortion rights are far more politically polarizing.

As the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade , the US Supreme Court case legalizing abortion, approaches, many Americans assume that legalized abortion is only as old as that ruling. In fact, as Anna Peterson discusses this month, abortion had only been made illegal at the turn of the 20th century. The different histories of abortion in Europe and the United States reveal much about the current state of American debates—so prominent in the 2012 elections campaigns—over abortion and women’s health.

*Update: for our podcast, we caught up with Anna Peterson during her research in Oslo, Norway.

For more from Origins on women's history, please read Women’s Rights in Afghanistan ; Women's Politics in Zimbabwe ; The Real Marriage Revolution ; Child Kidnapping in America ; and Abortion in Canada (PDF File) .

Representative Todd Akin (R-Missouri) caused a political firestorm this August when he told a television reporter that he opposes abortion in all circumstances because "legitimate rape" rarely leads to pregnancy. Republican Presidential candidate Mitt Romney quickly distanced his own pro-life views from Akin's, and President Barack Obama reiterated his commitment to not make "health care decisions on behalf of women."

Politicians frequently use their stances on abortion to elicit electoral support, and this election year is no different. Abortion is again a major point of divisive debate in presidential and congressional races. And state legislative efforts to restrict abortion access are currently under way in twelve states.

The 2012 Republican Party platform calls for a constitutional amendment to outlaw abortions but makes no explicit mention of whether exceptions would be made for cases of rape and incest. Romney has indicated in several interviews that he supports the repeal of Roe v. Wade .

Across the Atlantic, the abortion issue seldom garners such rapt attention. As members of national health insurance plans, most Western European women enjoy access to elective abortion services—also called abortion on demand. While there are significant regional differences in abortion policies and political discourse, abortion is rarely a point of contention during elections.

Abortion practices, debates, and laws initially developed quite similarly in Europe and the U.S., but at the turn of the twentieth century, cultural attitudes began to diverge. While Europeans continued to believe that abortion was a desperate act of unfortunate women, some powerful Americans began to argue that abortion was an immoral act of sinful women. These divergent perceptions of abortion and the women who have them still affect abortion debates and legislation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Historically, abortion policy has revolved around three main players: government officials, women, and medical practitioners.

The historical record also shows that, for thousands of years, women have limited the number of the children they bore through pregnancy prevention, abortion, and infanticide. Abortion was only recently outlawed, and then only for a period of roughly 100 years. When women did not have legal access to abortion services they still found ways (albeit often unsafe ways) to end unwanted pregnancies.

Abortion at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century

For most of Western history, aborting an early pregnancy was considered a private matter controlled by women and was not a crime.

At the turn of the nineteenth century most people in Western Europe and the United States did not believe human life was present until a pregnant woman felt the first fetal movements, a phenomenon referred to as quickening .

Before quickening, women thought about pregnancy in terms of a lack of something (menstruation) rather than the presence of something (a fetus). In an effort to restore their monthly periods, they took herbal abortifacients such as savin, pennyroyal, and ergot, which they often found in their own gardens.

They did not consider such practices abortion. In fact, the word abortion was confined to miscarriages that occurred after quickening. Medical doctors had trouble even verifying a pregnancy until the woman reported that quickening had occurred.

Religious authorities such as the Roman Catholic Church also supported the idea that the soul was not present until a later stage of pregnancy. Although not official church doctrine, this belief was based on St. Augustine's fifth-century interpretation of Aristotle, that the soul enters the body only after the body is fully formed—some 40 days after conception for males and 80 days for females.

Laws reflected this distinction between the quick and the nonquick fetus. In the United States and England, abortion was legal in the early 1800s as long as it was performed prior to quickening. During later stages of pregnancy, abortion was a crime, but distinct from other forms of murder and punished less harshly.

It was very difficult to prove that a woman accused of abortion had ever felt the fetus move. Even in infanticide cases, the court often had to rely on the accused woman's testimony to know whether the child had died in utero or had been born full-term and alive.

When Margaret Rauch was put on trial in Pennsylvania in 1772 for a suspected infanticide, she testified that the baby "used to move before, but did not move after [she fell during the pregnancy]." Rauch was acquitted.

At this time, the pregnant woman had significant power in defining pregnancy and the law was based on her bodily experience.

By the mid-1800s women from all walks of life aborted pregnancies, and abortion services had grown more widely available. As the professionalization and commercialization of medicine began, more abortion options became available to the women who could afford to pay for them.

Poor women—especially unmarried ones—continued to use herbs to abort unwanted pregnancies, and could purchase abortifacients from pharmacists through the mail. If those drugs failed they could go to the growing number of practices that used medical instruments to induce abortions. Costing anywhere between $5 and $500, most women who could pay skilled professionals for such services were married members of the middle and upper classes.

The Road to Criminalization

In the late nineteenth century, American and European doctors, social reformers, clergy members, and politicians made abortion into a social, political, and religious issue. Women's experiences of quickening were discredited as unscientific and medical doctors became the recognized experts on pregnancy and fetal development.

Quickening lost credibility as a valid indication of fetal life when doctors lobbied state governments to change laws to reflect their new way of thinking. By 1900, Western European countries and the United States had outlawed abortion during all stages of pregnancy.