- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Religion and Science

The relationship between religion and science is the subject of continued debate in philosophy and theology. To what extent are religion and science compatible? Are religious beliefs sometimes conducive to science, or do they inevitably pose obstacles to scientific inquiry? The interdisciplinary field of “science and religion”, also called “theology and science”, aims to answer these and other questions. It studies historical and contemporary interactions between these fields, and provides philosophical analyses of how they interrelate.

This entry provides an overview of the topics and discussions in science and religion. Section 1 outlines the scope of both fields, and how they are related. Section 2 looks at the relationship between science and religion in five religious traditions, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism. Section 3 discusses contemporary topics of scientific inquiry in which science and religion intersect, focusing on divine action, creation, and human origins.

1.1 A brief history

1.2 what is science, and what is religion, 1.3 taxonomies of the interaction between science and religion, 1.4 the scientific study of religion, 2.1 christianity, 2.3 hinduism, 2.4 buddhism, 2.5 judaism, 3.1 divine action and creation, 3.2 human origins, works cited, other important works, other internet resources, related entries, 1. science, religion, and how they interrelate.

Since the 1960s, scholars in theology, philosophy, history, and the sciences have studied the relationship between science and religion. Science and religion is a recognized field of study with dedicated journals (e.g., Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science ), academic chairs (e.g., the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford University), scholarly societies (e.g., the Science and Religion Forum), and recurring conferences (e.g., the European Society for the Study of Science and Theology’s biennial meetings). Most of its authors are theologians (e.g., John Haught, Sarah Coakley), philosophers with an interest in science (e.g., Nancey Murphy), or (former) scientists with long-standing interests in religion, some of whom are also ordained clergy (e.g., the physicist John Polkinghorne, the molecular biophysicist Alister McGrath, and the atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe). Recently, authors in science and religion also have degrees in that interdisciplinary field (e.g., Sarah Lane Ritchie).

The systematic study of science and religion started in the 1960s, with authors such as Ian Barbour (1966) and Thomas F. Torrance (1969) who challenged the prevailing view that science and religion were either at war or indifferent to each other. Barbour’s Issues in Science and Religion (1966) set out several enduring themes of the field, including a comparison of methodology and theory in both fields. Zygon, the first specialist journal on science and religion, was also founded in 1966. While the early study of science and religion focused on methodological issues, authors from the late 1980s to the 2000s developed contextual approaches, including detailed historical examinations of the relationship between science and religion (e.g., Brooke 1991). Peter Harrison (1998) challenged the warfare model by arguing that Protestant theological conceptions of nature and humanity helped to give rise to science in the seventeenth century. Peter Bowler (2001, 2009) drew attention to a broad movement of liberal Christians and evolutionists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who aimed to reconcile evolutionary theory with religious belief. In the 1990s, the Vatican Observatory (Castel Gandolfo, Italy) and the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (Berkeley, California) co-sponsored a series of conferences on divine action and how it can be understood in the light of various contemporary sciences. This resulted in six edited volumes (see Russell, Murphy, & Stoeger 2008 for a book-length summary of the findings of this project).

The field has presently diversified so much that contemporary discussions on religion and science tend to focus on specific disciplines and questions. Rather than ask if religion and science (broadly speaking) are compatible, productive questions focus on specific topics. For example, Buddhist modernists (see section 2.4 ) have argued that Buddhist theories about the self (the no-self) and Buddhist practices, such as mindfulness meditation, are compatible and are corroborated by neuroscience.

In the contemporary public sphere, a prominent interaction between science and religion concerns evolutionary theory and creationism/Intelligent Design. The legal battles (e.g., the Kitzmiller versus Dover trial in 2005) and lobbying surrounding the teaching of evolution and creationism in American schools suggest there’s a conflict between religion and science. However, even if one were to focus on the reception of evolutionary theory, the relationship between religion and science is complex. For instance, in the United Kingdom, scientists, clergy, and popular writers (the so-called Modernists), sought to reconcile science and religion during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, whereas the US saw the rise of a fundamentalist opposition to evolutionary thinking, exemplified by the Scopes trial in 1925 (Bowler 2001, 2009).

Another prominent offshoot of the discussion on science and religion is the New Atheist movement, with authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens. They argue that public life, including government, education, and policy should be guided by rational argument and scientific evidence, and that any form of supernaturalism (especially religion, but also, e.g., astrology) has no place in public life. They treat religious claims, such as the existence of God, as testable scientific hypotheses (see, e.g., Dawkins 2006).

In recent decades, the leaders of some Christian churches have issued conciliatory public statements on evolutionary theory. Pope John Paul II (1996) affirmed evolutionary theory in his message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, but rejected it for the human soul, which he saw as the result of a separate, special creation. The Church of England publicly endorsed evolutionary theory (e.g., C. M. Brown 2008), including an apology to Charles Darwin for its initial rejection of his theory.

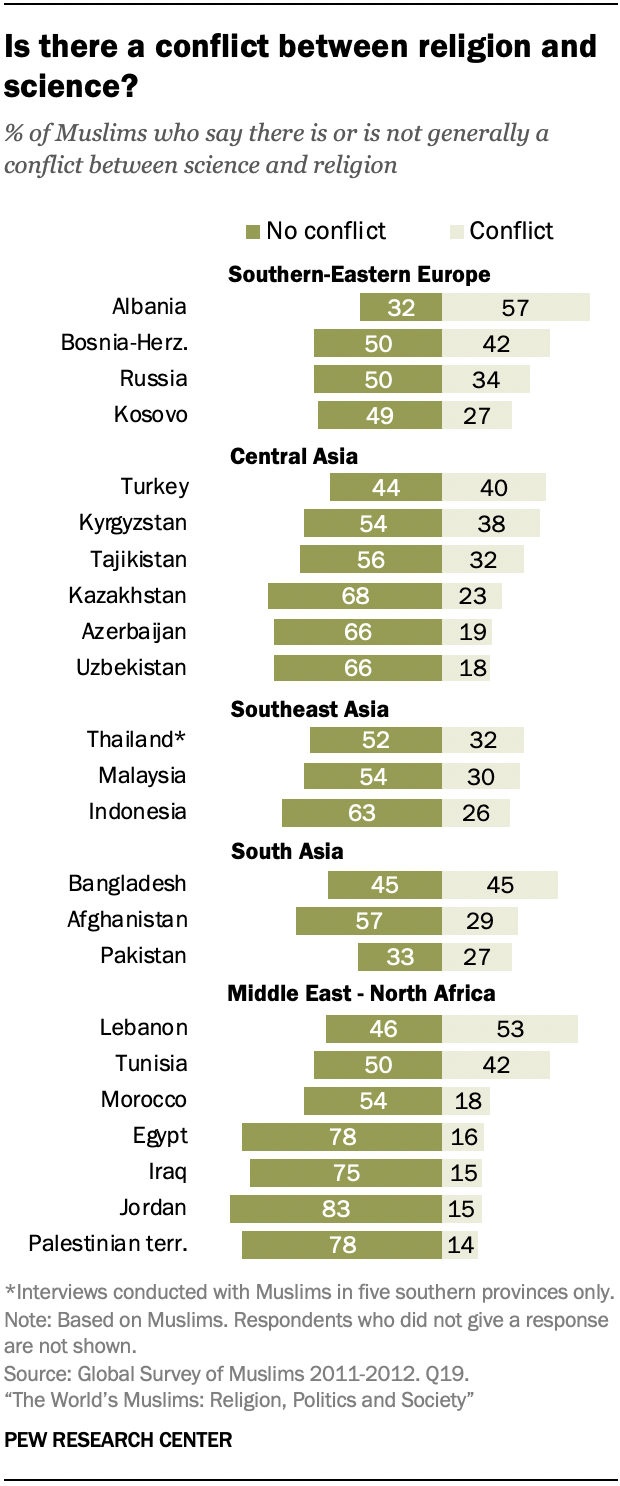

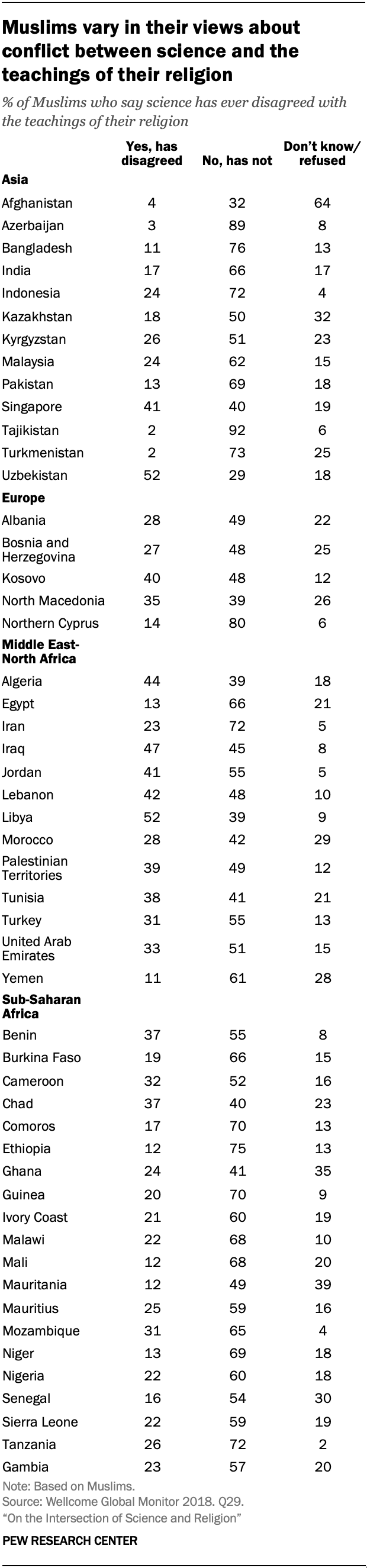

This entry will focus on the relationship between religious and scientific ideas as rather abstract philosophical positions, rather than as practices. However, this relationship has a large practical impact on the lives of religious people and scientists (including those who are both scientists and religious believers). A rich sociological literature indicates the complexity of these interactions, among others, how religious scientists conceive of this relationship (for recent reviews, see Ecklund 2010, 2021; Ecklund & Scheitle 2007; Gross & Simmons 2009).

For the past fifty years, the discussion on science and religion has de facto been on Western science and Christianity: to what extent can the findings of Western sciences be reconciled with Christian beliefs? The field of science and religion has only recently turned to an examination of non-Christian traditions, providing a richer picture of interaction.

In order to understand the scope of science and religion and their interactions, we must at least get a rough sense of what science and religion are. After all, “science” and “religion” are not eternally unchanging terms with unambiguous meanings. Indeed, they are terms that were coined recently, with meanings that vary across contexts. Before the nineteenth century, the term “religion” was rarely used. For a medieval author such as Aquinas, the term religio meant piety or worship, and was not applied to religious systems outside of what he considered orthodoxy (Harrison 2015). The term “religion” obtained its considerably broader current meaning through the works of early anthropologists, such as E.B. Tylor (1871), who systematically used the term for religions across the world. As a result, “religion” became a comparative concept, referring to traits that could be compared and scientifically studied, such as rituals, dietary restrictions, and belief systems (Jonathan Smith 1998).

The term “science” as it is currently used also became common in the nineteenth century. Prior to this, what we call “science” fell under the terminology of “natural philosophy” or, if the experimental part was emphasized, “experimental philosophy”. William Whewell (1834) standardized the term “scientist” to refer to practitioners of diverse natural philosophies. Philosophers of science have attempted to demarcate science from other knowledge-seeking endeavors, in particular religion. For instance, Karl Popper (1959) claimed that scientific hypotheses (unlike religious and philosophical ones) are in principle falsifiable. Many authors (e.g., Taylor 1996) affirm a disparity between science and religion, even if the meanings of both terms are historically contingent. They disagree, however, on how to precisely (and across times and cultures) demarcate the two domains.

One way to distinguish between science and religion is the claim that science concerns the natural world, whereas religion concerns the supernatural world and its relationship to the natural. Scientific explanations do not appeal to supernatural entities such as gods or angels (fallen or not), or to non-natural forces (such as miracles, karma, or qi ). For example, neuroscientists typically explain our thoughts in terms of brain states, not by reference to an immaterial soul or spirit, and legal scholars do not invoke karmic load when discussing why people commit crimes.

Naturalists draw a distinction between methodological naturalism , an epistemological principle that limits scientific inquiry to natural entities and laws, and ontological or philosophical naturalism , a metaphysical principle that rejects the supernatural (Forrest 2000). Since methodological naturalism is concerned with the practice of science (in particular, with the kinds of entities and processes that are invoked), it does not make any statements about whether or not supernatural entities exist. They might exist, but lie outside of the scope of scientific investigation. Some authors (e.g., Rosenberg 2014) hold that taking the results of science seriously entails negative answers to such persistent questions into the existence of free will or moral knowledge. However, these stronger conclusions are controversial.

The view that science can be demarcated from religion in its methodological naturalism is more commonly accepted. For instance, in the Kitzmiller versus Dover trial, the philosopher of science Robert Pennock was called to testify by the plaintiffs on whether Intelligent Design was a form of creationism, and therefore religion. If it were, the Dover school board policy would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Building on earlier work (e.g., Pennock 1998), Pennock argued that Intelligent Design, in its appeal to supernatural mechanisms, was not methodologically naturalistic, and that methodological naturalism is an essential component of science.

Methodological naturalism is a recent development in the history of science, though we can see precursors of it in medieval authors such as Aquinas who attempted to draw a theological distinction between miracles, such as the working of relics, and unusual natural phenomena, such as magnetism and the tides (see Perry & Ritchie 2018). Natural and experimental philosophers such as Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, Robert Hooke, and Robert Boyle regularly appealed to supernatural agents in their natural philosophy (which we now call “science”). Still, overall there was a tendency to favor naturalistic explanations in natural philosophy. The X-club was a lobby group for the professionalization of science founded in 1864 by Thomas Huxley and friends. While the X-club may have been in part motivated by the desire to remove competition by amateur-clergymen scientists in the field of science, and thus to open up the field to full-time professionals, its explicit aim was to promote a science that would be free from religious dogma (Garwood 2008, Barton 2018). This preference for naturalistic causes may have been encouraged by past successes of naturalistic explanations, leading authors such as Paul Draper (2005) to argue that the success of methodological naturalism could be evidence for ontological naturalism.

Several typologies probe the interaction between science and religion. For example, Mikael Stenmark (2004) distinguishes between three views: the independence view (no overlap between science and religion), the contact view (some overlap between the fields), and a union of the domains of science and religion; within these views he recognizes further subdivisions, e.g., contact can be in the form of conflict or harmony. The most influential taxonomy of the relationship between science and religion remains Barbour’s (2000): conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration. Subsequent authors, as well as Barbour himself, have refined and amended this taxonomy. However, others (e.g., Cantor & Kenny 2001) have argued that this taxonomy is not useful to understand past interactions between both fields. Nevertheless, because of its enduring influence, it is still worthwhile to discuss it in detail.

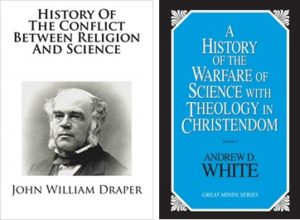

The conflict model holds that science and religion are in perpetual and principal conflict. It relies heavily on two historical narratives: the trial of Galileo (see Dawes 2016) and the reception of Darwinism (see Bowler 2001). Contrary to common conception, the conflict model did not originate in two seminal publications, namely John Draper’s (1874) History of the Conflict between Religion and Science and Andrew Dickson White’s (1896) two-volume opus A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom . Rather, as James Ungureanu (2019) argues, the project of these early architects of the conflict thesis needs to be contextualized in a liberal Protestant tradition of attempting to separate religion from theology, and thus salvage religion. Their work was later appropriated by skeptics and atheists who used their arguments about the incompatibility of traditional theological views with science to argue for secularization, something Draper and White did not envisage.

The vast majority of authors in the science and religion field is critical of the conflict model and believes it is based on a shallow and partisan reading of the historical record. While the conflict model is at present a minority position, some have used philosophical argumentation (e.g., Philipse 2012) or have carefully re-examined historical evidence such as the Galileo trial (e.g., Dawes 2016) to argue for this model. Alvin Plantinga (2011) has argued that the conflict is not between science and religion, but between science and naturalism. In his Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism (first formulated in 1993), Plantinga argues that naturalism is epistemically self-defeating: if both naturalism and evolution are true, then it’s unlikely we would have reliable cognitive faculties.

The independence model holds that science and religion explore separate domains that ask distinct questions. Stephen Jay Gould developed an influential independence model with his NOMA principle (“Non-Overlapping Magisteria”):

The lack of conflict between science and religion arises from a lack of overlap between their respective domains of professional expertise. (2001: 739)

He identified science’s areas of expertise as empirical questions about the constitution of the universe, and religion’s domain of expertise as ethical values and spiritual meaning. NOMA is both descriptive and normative: religious leaders should refrain from making factual claims about, for instance, evolutionary theory, just as scientists should not claim insight on moral matters. Gould held that there might be interactions at the borders of each magisterium, such as our responsibility toward other living things. One obvious problem with the independence model is that if religion were barred from making any statement of fact, it would be difficult to justify its claims of value and ethics. For example, one could not argue that one should love one’s neighbor because it pleases the creator (Worrall 2004). Moreover, religions do seem to make empirical claims, for example, that Jesus appeared after his death or that the early Hebrews passed through the parted waters of the Red Sea.

The dialogue model proposes a mutualistic relationship between religion and science. Unlike independence, it assumes a common ground between both fields, perhaps in their presuppositions, methods, and concepts. For example, the Christian doctrine of creation may have encouraged science by assuming that creation (being the product of a designer) is both intelligible and orderly, so one can expect there are laws that can be discovered. Creation, as a product of God’s free actions, is also contingent, so the laws of nature cannot be learned through a priori thinking which prompts the need for empirical investigation. According to Barbour (2000), both scientific and theological inquiry are theory-dependent, or at least model-dependent. For example, the doctrine of the Trinity colors how Christian theologians interpret the first chapters of Genesis. Next to this, both rely on metaphors and models. Both fields remain separate but they talk to each other, using common methods, concepts, and presuppositions. Wentzel van Huyssteen (1998) has argued for a dialogue position, proposing that science and religion can be in a graceful duet, based on their epistemological overlaps. The Partially Overlapping Magisteria (POMA) model defended by Alister McGrath (e.g., McGrath and Collicutt McGrath 2007) is also worth mentioning. According to McGrath, science and religion each draw on several different methodologies and approaches. These methods and approaches are different ways of knowing that have been shaped through historical factors. It is beneficial for scientists and theologians to be in dialogue with each other.

The integration model is more extensive in its unification of science and theology. Barbour (2000) identifies three forms of integration. First, natural theology, which formulates arguments for the existence and attributes of God. It uses interpretations of results from the natural sciences as premises in its arguments. For instance, the supposition that the universe has a temporal origin features in contemporary cosmological arguments for the existence of God. Likewise, the fact that the cosmological constants and laws of nature are life-permitting (whereas many other combinations of constants and laws would not permit life) is used in contemporary fine-tuning arguments (see the entry to fine-tuning arguments ). Second, theology of nature starts not from science but from a religious framework, and examines how this can enrich or even revise findings of the sciences. For example, McGrath (2016) developed a Christian theology of nature, examining how nature and scientific findings can be interpreted through a Christian lens. Thirdly, Barbour believed that Whitehead’s process philosophy was a promising way to integrate science and religion.

While integration seems attractive (especially to theologians), it is difficult to do justice to both the scientific and religious aspects of a given domain, especially given their complexities. For example, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1971), who was both knowledgeable in paleoanthropology and theology, ended up with an unconventional view of evolution as teleological (which put him at odds with the scientific establishment) and with an unorthodox theology (which denied original sin and led to a series of condemnations by the Roman Catholic Church). Theological heterodoxy, by itself, is no reason to doubt a model. However, it shows obstacles for the integration model to become a live option in the broader community of theologians and philosophers who want to remain affiliate to a specific religious community without transgressing its boundaries. Moreover, integration seems skewed towards theism: Barbour described arguments based on scientific results that support (but do not demonstrate) theism, but failed to discuss arguments based on scientific results that support (but do not demonstrate) the denial of theism. Hybrid positions like McGrath’s POMA indicate some difficulty for Barbour’s taxonomy: the scope of conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration is not clearly defined and they are not mutually exclusive. For example, if conflict is defined broadly then it is compatible with integration. Take the case of Frederick Tennant (1902), who sought to explain sin as the result of evolutionary pressures on human ancestors. This view led him to reject the Fall as a historical event, as it was not compatible with evolutionary biology. His view has conflict (as he saw Christian doctrine in conflict with evolutionary biology) but also integration (he sought to integrate the theological concept of sin in an evolutionary picture). It is clear that many positions defined by authors in the religion and science literature do not clearly fall within one of Barbour’s four domains.

Science and religion are closely interconnected in the scientific study of religion, which can be traced back to seventeenth-century natural histories of religion. Natural historians attempted to provide naturalistic explanations for human behavior and culture, including religion and morality. For example, Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle’s De l’Origine des Fables (1724) offered a causal account of belief in the supernatural. People often assert supernatural explanations when they lack an understanding of the natural causes underlying extraordinary events: “To the extent that one is more ignorant, or one has less experience, one sees more miracles” (1724 [1824: 295], my translation). Hume’s Natural History of Religion (1757) is perhaps the best-known philosophical example of a natural historical explanation of religious belief. It traces the origins of polytheism—which Hume thought was the earliest form of religious belief—to ignorance about natural causes combined with fear and apprehension about the environment. By deifying aspects of the environment, early humans tried to persuade or bribe the gods, thereby gaining a sense of control.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, authors from newly emerging scientific disciplines, such as anthropology, sociology, and psychology examined the purported naturalistic roots of religious beliefs. They did so with a broad brush, trying to explain what unifies diverse religious beliefs across cultures. Auguste Comte (1841) proposed that all societies, in their attempts to make sense of the world, go through the same stages of development: the theological (religious) stage is the earliest phase, where religious explanations predominate, followed by the metaphysical stage (a non-intervening God), and culminating in the positive or scientific stage, marked by scientific explanations and empirical observations.

In anthropology, this positivist idea influenced cultural evolutionism, a theoretical framework that sought to explain cultural change using universal patterns. The underlying supposition was that all cultures evolve and progress along the same trajectory. Cultures with differing religious views were explained as being in different stages of their development. For example, Tylor (1871) regarded animism as the earliest form of religious belief. James Frazer’s Golden Bough (1890) is somewhat unusual within this literature, as he saw commonalities between magic, religion, and science. Though he proposed a linear progression, he also argued that a proto-scientific mindset gave rise to magical practices, including the discovery of regularities in nature. Cultural evolutionist models dealt poorly with religious diversity and with the complex relationships between science and religion across cultures. Many authors proposed that religion was just a stage in human development, which would eventually be superseded. For example, social theorists such as Karl Marx and Max Weber proposed versions of the secularization thesis, the view that religion would decline in the face of modern technology, science, and culture.

Functionalism was another theoretical framework that sought to explain religion. Functionalists did not consider religion to be a stage in human cultural development that would eventually be overcome. They saw it as a set of social institutions that served important functions in the societies they were part of. For example, the sociologist Émile Durkheim (1912 [1915]) argued that religious beliefs are social glue that helps to keep societies together.

Sigmund Freud and other early psychologists aimed to explain religion as the result of cognitive dispositions. For example, Freud (1927) saw religious belief as an illusion, a childlike yearning for a fatherly figure. He also considered “oceanic feeling” (a feeling of limitlessness and of being connected with the world, a concept he derived from the French author Romain Rolland) as one of the origins of religious belief. He thought this feeling was a remnant of an infant’s experience of the self, prior to being weaned off the breast. William James (1902) was interested in the psychological roots and the phenomenology of religious experiences, which he believed were the ultimate source of all institutional religions.

From the 1920s onward, the scientific study of religion became less concerned with grand unifying narratives, and focused more on particular religious traditions and beliefs. Anthropologists such as Edward Evans-Pritchard (1937) and Bronisław Malinowski (1925) no longer relied exclusively on second-hand reports (usually of poor quality and from distorted sources), but engaged in serious fieldwork. Their ethnographies indicated that cultural evolutionism was a defective theoretical framework and that religious beliefs were more diverse than was previously assumed. They argued that religious beliefs were not the result of ignorance of naturalistic mechanisms. For instance, Evans-Pritchard (1937) noted that the Azande were well aware that houses could collapse because termites ate away at their foundations, but they still appealed to witchcraft to explain why a particular house collapsed at a particular time. More recently, Cristine Legare et al. (2012) found that people in various cultures straightforwardly combine supernatural and natural explanations, for instance, South Africans are aware AIDS is caused by the HIV virus, but some also believe that the viral infection is ultimately caused by a witch.

Psychologists and sociologists of religion also began to doubt that religious beliefs were rooted in irrationality, psychopathology, and other atypical psychological states, as James (1902) and other early psychologists had assumed. In the US, in the late 1930s through the 1960s, psychologists developed a renewed interest for religion, fueled by the observation that religion refused to decline and seemed to undergo a substantial revival, thus casting doubt on the secularization thesis (see Stark 1999 for an overview). Psychologists of religion have made increasingly fine-grained distinctions between types of religiosity, including extrinsic religiosity (being religious as means to an end, for instance, getting the benefits of being a member of a social group) and intrinsic religiosity (people who adhere to religions for the sake of their teachings) (Allport & Ross 1967). Psychologists and sociologists now commonly study religiosity as an independent variable, with an impact on, for instance, health, criminality, sexuality, socio-economic profile, and social networks.

A recent development in the scientific study of religion is the cognitive science of religion (CSR). This is a multidisciplinary field, with authors from, among others, developmental psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and cognitive psychology (see C. White 2021 for a comprehensive overview). It differs from other scientific approaches to religion in its presupposition that religion is not a purely cultural phenomenon. Rather, authors in CSR hold that religion is the result of ordinary, early developed, and universal human cognitive processes (e.g., Barrett 2004, Boyer 2002). Some authors regard religion as the byproduct of cognitive processes that are not evolved for religion. For example, according to Paul Bloom (2007), religion emerges as a byproduct of our intuitive distinction between minds and bodies: we can think of minds as continuing, even after the body dies (e.g., by attributing desires to a dead family member), which makes belief in an afterlife and in disembodied spirits natural and spontaneous. Another family of hypotheses regards religion as a biological or cultural adaptive response that helps humans solve cooperative problems (e.g., Bering 2011; Purzycki & Sosis 2022): through their belief in big, powerful gods that can punish, humans behave more cooperatively, which allowed human group sizes to expand beyond small hunter-gatherer communities. Groups with belief in big gods thus out-competed groups without such beliefs for resources during the Neolithic, which would explain the current success of belief in such gods (Norenzayan 2013). However, the question of which came first—big god beliefs or large-scale societies—is a continued matter of debate.

2. Science and religion in various religions

As noted, most studies on the relationship between science and religion have focused on science and Christianity, with only a small number of publications devoted to other religious traditions (e.g., Brooke & Numbers 2011; Lopez 2008). Since science makes universal claims, it is easy to assume that its encounter with other religious traditions would be similar to its interactions with Christianity. However, given different creedal tenets (e.g., in Hindu traditions God is usually not entirely distinct from creation, unlike in Christianity and Judaism), and because science has had distinct historical trajectories in other cultures, one can expect disanalogies in the relationship between science and religion in different religious traditions. To give a sense of this diversity, this section provides a bird’s eye view of science and religion in five major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, currently the religion with the most adherents. It developed in the first century CE out of Judaism. Christians adhere to asserted revelations described in a series of canonical texts, which include the Old Testament, which comprises texts inherited from Judaism, and the New Testament, which contains the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (narratives on the life and teachings of Jesus), as well as events and teachings of the early Christian churches (e.g., Acts of the Apostles, letters by Paul), and Revelation, a prophetic book on the end times.

Given the prominence of revealed texts in Christianity, a useful starting point to examine the relationship between Christianity and science is the two books metaphor (see Tanzella-Nitti 2005 for an overview): God revealed Godself through the “Book of Nature”, with its orderly laws, and the “Book of Scripture”, with its historical narratives and accounts of miracles. Augustine (354–430) argued that the book of nature was the more accessible of the two, since scripture requires literacy whereas illiterates and literates alike could read the book of nature. Maximus Confessor (c. 580–662), in his Ambigua (see Louth 1996 for a collection of and critical introduction to these texts) compared scripture and natural law to two clothes that envelop the Incarnated Logos: Jesus’ humanity is revealed by nature, whereas his divinity is revealed by the scriptures. During the Middle Ages, authors such as Hugh of St. Victor (ca. 1096–1141) and Bonaventure (1221–1274) began to realize that the book of nature was not at all straightforward to read. Given that original sin marred our reason and perception, what conclusions could humans legitimately draw about ultimate reality? Bonaventure used the metaphor of the books to the extent that “ liber naturae ” was a synonym for creation, the natural world. He argued that sin has clouded human reason so much that the book of nature has become unreadable, and that scripture is needed as an aid as it contains teachings about the world.

Christian authors in the field of science and religion continue to debate how these two books interrelate. Concordism is the attempt to interpret scripture in the light of modern science. It is a hermeneutical approach to Bible interpretation, where one expects that the Bible foretells scientific theories, such as the Big Bang theory or evolutionary theory. However, as Denis Lamoureux (2008: chapter 5) argues, many scientific-sounding statements in the Bible are false: the mustard seed is not the smallest seed, male reproductive seeds do not contain miniature persons, there is no firmament, and the earth is neither flat nor immovable. Thus, any plausible form of integrating the book of nature and scripture will require more nuance and sophistication. Theologians such as John Wesley (1703–1791) have proposed the addition of other sources of knowledge to scripture and science: the Wesleyan quadrilateral (a term not coined by Wesley himself) is the dynamic interaction of scripture, experience (including the empirical findings of the sciences), tradition, and reason (Outler 1985).

Several Christian authors have attempted to integrate science and religion (e.g., Haught 1995, Lamoureux 2008, Murphy 1995), making integration a highly popular view on the relationship between science and religion. These authors tend to interpret findings from the sciences, such as evolutionary theory or chaos theory, in a theological light, using established theological models such as classical theism or the doctrine of creation. John Haught (1995) argues that the theological view of kenosis (self-emptying of God in creation) anticipates scientific findings such as evolutionary theory: a self-emptying God (i.e., who limits Godself), who creates a distinct and autonomous world, makes a world with internal self-coherence, with a self-organizing universe as the result.

The dominant epistemological outlook in Christian science and religion has been critical realism, a position that applies both to theology (theological realism) and to science (scientific realism). Barbour (1966) introduced this view into the science and religion literature; it has been further developed by theologians such as Arthur Peacocke (1984) and Wentzel van Huyssteen (1999). Critical realism aims to offer a middle way between naïve realism (the world is as we perceive it) and instrumentalism (our perceptions and concepts are purely instrumental). It encourages critical reflection on perception and the world, hence “critical”. Critical realism has distinct flavors in the works of different authors, for instance, van Huyssteen (1998, 1999) develops a weak form of critical realism set within a postfoundationalist notion of rationality, where theological views are shaped by social, cultural, and evolved biological factors. Murphy (1995: 329–330) outlines doctrinal and scientific requirements for approaches in science and religion: ideally, an integrated approach should be broadly in line with Christian doctrine, especially core tenets such as the doctrine of creation, while at the same time it should be in line with empirical observations without undercutting scientific practices.

Several historians (e.g., Hooykaas 1972) have argued that Christianity was instrumental to the development of Western science. Peter Harrison (2007) maintains that the doctrine of original sin played a crucial role in this, arguing there was a widespread belief in the early modern period that Adam, prior to the Fall, had superior senses, intellect, and understanding. As a result of the Fall, human senses became duller, our ability to make correct inferences was diminished, and nature itself became less intelligible. Postlapsarian humans (i.e., humans after the Fall) are no longer able to exclusively rely on their a priori reasoning to understand nature. They must supplement their reasoning and senses with observation through specialized instruments, such as microscopes and telescopes. As the experimental philosopher Robert Hooke wrote in the introduction to his Micrographia :

every man, both from a deriv’d corruption, innate and born with him, and from his breeding and converse with men, is very subject to slip into all sorts of errors … These being the dangers in the process of humane Reason, the remedies of them all can only proceed from the real, the mechanical, the experimental Philosophy [experiment-based science]. (1665, cited in Harrison 2007: 5)

Another theological development that may have facilitated the rise of science was the Condemnation of Paris (1277), which forbade teaching and reading natural philosophical views that were considered heretical, such as Aristotle’s physical treatises. As a result, the Condemnation opened up intellectual space to think beyond ancient Greek natural philosophy. For example, medieval philosophers such as John Buridan (fl. 14th c) held the Aristotelian belief that there could be no vacuum in nature, but once the idea of a vacuum became plausible, natural philosophers such as Evangelista Torricelli (1608–1647) and Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) could experiment with air pressure and vacua (see Grant 1996, for discussion).

Some authors claim that Christianity was unique and instrumental in catalyzing the scientific revolution. For example, according to the sociologist of religion Rodney Stark (2004), the scientific revolution was in fact a slow, gradual development from medieval Christian theology. Claims such as Stark’s, however, fail to recognize the legitimate contributions of Islamic and Greek scholars to the development of modern science, and fail to do justice to the importance of practical technological innovations in map-making and star-charting in the emergence of modern science. In spite of these positive readings of the relationship between science and religion in Christianity, there are sources of enduring tension. For example, there is still vocal opposition to the theory of evolution among Christian fundamentalists. In the public sphere, the conflict view between Christianity and science prevails, in stark contrast to the scholarly literature. This is due to an important extent to the outsize influence of a vocal conservative Christian minority in the American public debate, which sidelines more moderate voices (Evans 2016).

Islam is a monotheistic religion that emerged in the seventh century, following a series of purported revelations to the prophet Muḥammad. The term “Islam” also denotes geo-political structures, such as caliphates and empires, which were founded by Muslim rulers from the seventh century onward, including the Umayyad, Abbasid, and Ottoman caliphates. Additionally, it refers to a culture which flourished within this political and religious context, with its own philosophical and scientific traditions (Dhanani 2002). The defining characteristic of Islam is belief in one God (Allāh), who communicates through prophets, including Adam, Abraham, and Muḥammad. Allāh’s revelations to Muḥammad are recorded in the Qurʾān, the central religious text for Islam. Next to the Qurʾān, an important source of jurisprudence and theology is the ḥadīth, an oral corpus of attested sayings, actions, and tacit approvals of the prophet Muḥammad. The two major branches of Islam, Sunni and Shia, are based on a dispute over the succession of Muḥammad. As the second largest religion in the world, Islam shows a wide variety of beliefs. Core creedal views include the oneness of God ( tawḥīd ), the view that there is only one undivided God who created and sustains the universe, prophetic revelation (in particular to Muḥammad), and an afterlife. Beyond this, Muslims disagree on a number of doctrinal issues.

The relationship between Islam and science is complex. Today, predominantly Muslim countries, such as the United Arabic Emirates, enjoy high urbanization and technological development, but they still underperform in common metrics of scientific research, such as publications in leading journals and number of citations per scientist, compared to other regions outside of the west such as India and China (see Edis 2007). Some Muslims hold a number of pseudoscientific ideas, some of which it shares with Christianity such as Old Earth creationism, whereas others are specific to Islam such as the recreation of human bodies from the tailbone on the day of resurrection, and the superiority of prayer in treating lower-back pain instead of conventional methods (Guessoum 2011: 4–5).

This contemporary lack of scientific prominence is remarkable given that the Islamic world far exceeded European cultures in the range and quality of its scientific knowledge between approximately the ninth and the fifteenth century, excelling in domains such as mathematics (algebra and geometry, trigonometry in particular), astronomy (seriously considering, but not adopting, heliocentrism), optics, and medicine. These domains of knowledge are commonly referred to as “Arabic science”, to distinguish them from the pursuits of science that arose in the west (Huff 2003). “Arabic science” is an imperfect term, as many of the practitioners were not speakers of Arabic, hence the term “science in the Islamic world” is more accurate. Many scientists in the Islamic world were polymaths, for example, Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna, 980–1037) is commonly regarded as one of the most significant innovators, not only in philosophy, but also in medicine and astronomy. His Canon of Medicine , a medical encyclopedia, was a standard textbook in universities across Europe for many centuries after his death. Al-Fārābī (ca. 872–ca. 950), a political philosopher from Damascus, also investigated music theory, science, and mathematics. Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) achieved lasting fame in disparate domains such as poetry, astronomy, geography, and mineralogy. The Andalusian Ibn Rušd (Averroes, 1126–1198) wrote on medicine, physics, astronomy, psychology, jurisprudence, music, and geography, next to developing a Greek-inspired philosophical theology.

A major impetus for science in the Islamic world was the patronage of the Abbasid caliphate (758–1258), centered in Baghdad. Early Abbasid rulers, such as Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786–809) and his successor Abū Jaʿfar Abdullāh al-Ma’mūn (ruled 813–833), were significant patrons of science. The former founded the Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom), which commissioned translations of major works by Aristotle, Galen, and many Persian and Indian scholars into Arabic. It was cosmopolitan in its outlook, employing astronomers, mathematicians, and physicians from abroad, including Indian mathematicians and Nestorian (Christian) astronomers. Throughout the Islamic world, public libraries attached to mosques provided access to a vast compendium of knowledge, which spread Islam, Greek philosophy, and science. The use of a common language (Arabic), as well as common religious and political institutions and flourishing trade relations encouraged the spread of scientific ideas throughout the Islamic world. Some of this transmission was informal, e.g., correspondence between like-minded people (see Dhanani 2002), some formal, e.g., in hospitals where students learned about medicine in a practical, master-apprentice setting, and in astronomical observatories and academies. The decline and fall of the Abbasid caliphate dealt a blow to science in the Islamic world, but it remains unclear why it ultimately stagnated, and why it did not experience something analogous to the scientific revolution in Western Europe. Note, the decline of science in the Islamic world should not be generalized to other fields, such as philosophy and philosophical theology, which continued to flourish after the Abbasid caliphate fell.

Some liberal Muslim authors, such as Fatima Mernissi (1992), argue that the rise of conservative forms of Islamic philosophical theology stifled more scientifically-minded natural philosophy. In the ninth to the twelfth century, the Mu’tazila (a philosophical theological school) helped the growth of science in the Islamic world thanks to their embrace of Greek natural philosophy. But eventually, the Mu’tazila and their intellectual descendants lost their influence to more conservative brands of theology. Al-Ghazālī’s influential eleventh-century work, The Incoherence of the Philosophers ( Tahāfut al-falāsifa ), was a scathing and sophisticated critique of Greek-inspired Muslim philosophy, arguing that their metaphysical assumptions could not be demonstrated. This book vindicated more orthodox Muslim religious views. As Muslim intellectual life became more orthodox, it became less open to non-Muslim philosophical ideas, which led to the decline of science in the Islamic world, according to this view.

The problem with this narrative is that orthodox worries about non-Islamic knowledge were already present before Al-Ghazālī and continued long after his death (Edis 2007: chapter 2). The study of law ( fiqh ) was more stifling for science in the Islamic world than developments in theology. The eleventh century saw changes in Islamic law that discouraged heterodox thought: lack of orthodoxy could now be regarded as apostasy from Islam ( zandaqa ) which is punishable by death, whereas before, a Muslim could only apostatize by an explicit declaration (Griffel 2009: 105). (Al-Ghazālī himself only regarded the violation of three core doctrines as zandaqa , namely statements that challenged monotheism, the prophecy of Muḥammad, and resurrection after death.) Given that heterodox thoughts could be interpreted as apostasy, this created a stifling climate for science. In the second half of the nineteenth century, as science and technology became firmly entrenched in Western society, Muslim empires were languishing or colonized. Scientific ideas, such as evolutionary theory, became equated with European colonialism, and thus met with distrust. The enduring association between western culture, colonialism, and science led to a more prominent conflict view of the relationship between science and religion in Muslim countries.

In spite of this negative association between science and Western modernity, there is an emerging literature on science and religion by Muslim scholars (mostly scientists). The physicist Nidhal Guessoum (2011) holds that science and religion are not only compatible, but in harmony. He rejects the idea of treating the Qurʾān as a scientific encyclopedia, something other Muslim authors in the debate on science and religion tend to do. Moreover, he adheres to the no-possible-conflict principle, outlined by Ibn Rušd: there can be no conflict between God’s word (properly understood) and God’s work (properly understood). If an apparent conflict arises, the Qurʾān may not have been interpreted correctly.

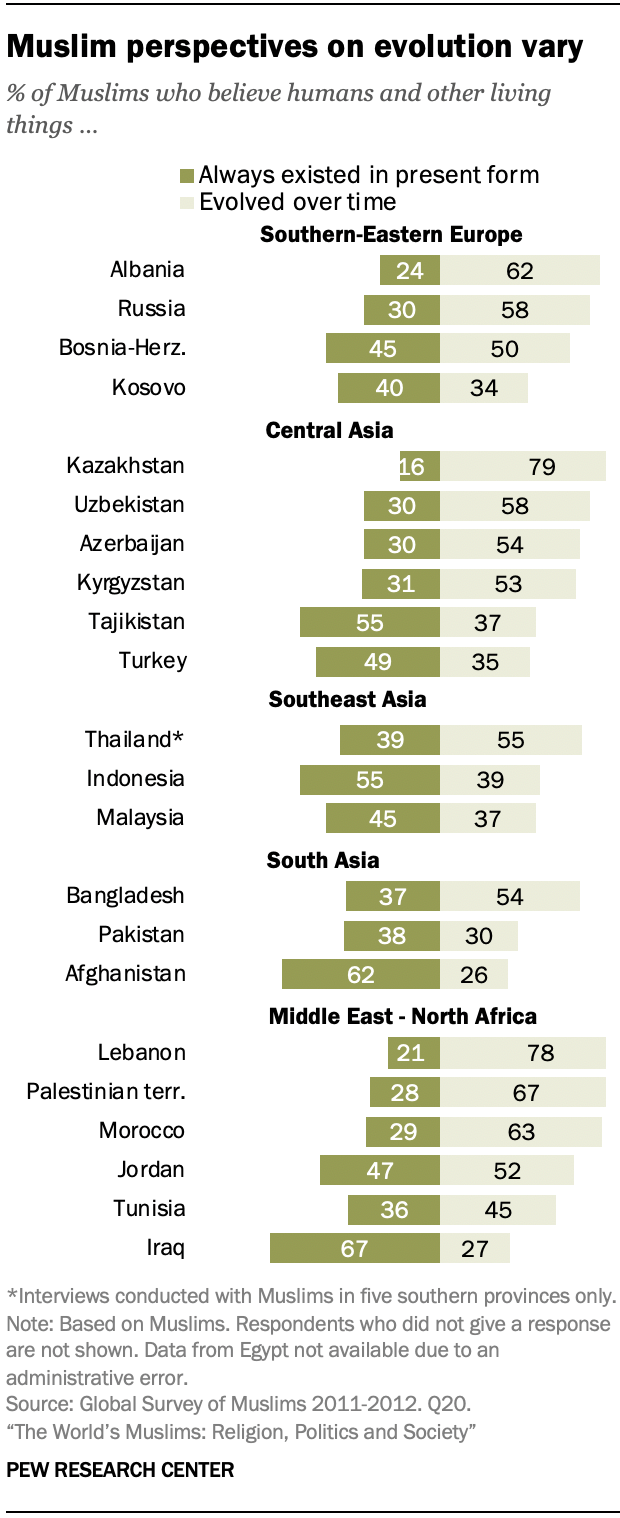

While the Qurʾān asserts a creation in six days (like the Hebrew Bible), “day” is often interpreted as a very long span of time, rather than a 24-hour period. As a result, Old Earth creationism is more influential in Islam than Young Earth creationism. Adnan Oktar’s Atlas of Creation (published in 2007 under the pseudonym Harun Yahya), a glossy coffee table book that draws heavily on Christian Old Earth creationism, has been distributed worldwide (Hameed 2008). Since the Qurʾān explicitly mentions the special creation of Adam out of clay, most Muslims refuse to accept that humans evolved from hominin ancestors. Nevertheless, Muslim scientists such as Guessoum (2011) and Rana Dajani (2015) have advocated acceptance of evolution.

Hinduism is the world’s third largest religion, though the term “Hinduism” is an awkward catch-all phrase that denotes diverse religious and philosophical traditions that emerged on the Indian subcontinent between 500 BCE and 300 CE. The vast majority of Hindus live in India; most others live in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia, with a significant diaspora in western countries such as the United States (Hackett 2015 [ Other Internet Resources ]). In contrast to the Abrahamic monotheistic religions, Hinduism does not always draw a sharp distinction between God and creation. (While there are pantheistic and panentheistic views in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, these are minority positions.) Many Hindus believe in a personal God, and identify this God as immanent in creation. This view has ramifications for the science and religion debate, in that there is no sharp ontological distinction between creator and creature (Subbarayappa 2011). Religious traditions originating on the Indian subcontinent, including Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism, are referred to as dharmic religions. Philosophical points of view are referred to as darśana .

One factor that unites the different strands of Hinduism is the importance of foundational texts composed between ca. 1600 and 700 BCE. These include the Vedas, which contain hymns and prescriptions for performing rituals, Brāhmaṇa, accompanying liturgical texts, and Upaniṣad, metaphysical treatises. The Vedas discuss gods who personify and embody natural phenomena such as fire (Agni) and wind (Vāyu). More gods appear in the following centuries (e.g., Gaṇeśa and Sati-Parvati in the 4th century). Note that there are both polytheistic and monotheistic strands in Hinduism, so it is not the case that individual believers worship or recognize all of these gods. Ancient Vedic rituals encouraged knowledge of diverse sciences, including astronomy, linguistics, and mathematics. Astronomical knowledge was required to determine the timing of rituals and the construction of sacrificial altars. Linguistics developed out of a need to formalize grammatical rules for classical Sanskrit, which was used in rituals. Large public offerings also required the construction of elaborate altars, which posed geometrical problems and thus led to advances in geometry. Classic Vedic texts also frequently used very large numbers, for instance, to denote the age of humanity and the Earth, which required a system to represent numbers parsimoniously, giving rise to a 10-base positional system and a symbolic representation for zero as a placeholder, which would later be imported in other mathematical traditions (Joseph 1991 [2000]). In this way, ancient Indian dharma encouraged the emergence of the sciences.

Around the sixth–fifth century BCE, the northern part of the Indian subcontinent experienced an extensive urbanization. In this context, medicine ( āyurveda ) became standardized. This period also gave rise to a wide range of heterodox philosophical schools, including Buddhism, Jainism, and Cārvāka. The latter defended a form of metaphysical naturalism, denying the existence of gods or karma. The relationship between science and religion on the Indian subcontinent is complex, in part because the dharmic religions and philosophical schools are so diverse. For example, Cārvāka proponents had a strong suspicion of inferential beliefs, and rejected Vedic revelation and supernaturalism in general, instead favoring direct observation as a source of knowledge.

Natural theology also flourished in the pre-colonial period, especially in the Advaita Vedānta, a darśana that identifies the self, ātman , with ultimate reality, Brahman. Advaita Vedāntin philosopher Adi Śaṅkara (fl. first half eighth century) was an author who regarded Brahman as the only reality, both the material and the efficient cause of the cosmos. Śaṅkara formulated design and cosmological arguments, drawing on analogies between the world and artifacts: in ordinary life, we never see non-intelligent agents produce purposive design, yet the universe is suitable for human life, just like benches and pleasure gardens are designed for us. Given that the universe is so complex that even an intelligent craftsman cannot comprehend it, how could it have been created by non-intelligent natural forces? Śaṅkara concluded that it must have been designed by an intelligent creator (C.M. Brown 2008: 108).

From 1757 to 1947, India was under British colonial rule. This had a profound influence on its culture as Hindus came into contact with Western science and technology. For local intellectuals, the contact with Western science presented a challenge: how to assimilate these ideas with Hinduism? Mahendrahal Sircar (1833–1904) was one of the first authors to examine evolutionary theory and its implications for Hindu religious beliefs. Sircar was an evolutionary theist, who believed that God used evolution to create current life forms. Evolutionary theism was not a new hypothesis in Hinduism, but the many lines of empirical evidence Darwin provided for evolution gave it a fresh impetus. While Sircar accepted organic evolution through common descent, he questioned the mechanism of natural selection as it was not teleological, which went against his evolutionary theism. This was a widespread problem for the acceptance of evolutionary theory, one that Christian evolutionary theists also wrestled with (Bowler 2009). He also argued against the British colonists’ beliefs that Hindus were incapable of scientific thought, and encouraged fellow Hindus to engage in science, which he hoped would help regenerate the Indian nation (C.M. Brown 2012: chapter 6).

The assimilation of Western culture prompted various revivalist movements that sought to reaffirm the cultural value of Hinduism. They put forward the idea of a Vedic science, where all scientific findings are already prefigured in the Vedas and other ancient texts (e.g., Vivekananda 1904). This idea is still popular within contemporary Hinduism, and is quite similar to ideas held by contemporary Muslims, who refer to the Qurʾān as a harbinger of scientific theories.

Responses to evolutionary theory were as diverse as Christian views on this subject, ranging from creationism (denial of evolutionary theory based on a perceived incompatibility with Vedic texts) to acceptance (see C.M. Brown 2012 for a thorough overview). Authors such as Dayananda Saraswati (1930–2015) rejected evolutionary theory. By contrast, Vivekananda (1863–1902), a proponent of the monistic Advaita Vedānta enthusiastically endorsed evolutionary theory and argued that it is already prefigured in ancient Vedic texts. His integrative view claimed that Hinduism and science are in harmony: Hinduism is scientific in spirit, as is evident from its long history of scientific discovery (Vivekananda 1904). Sri Aurobindo Ghose, a yogi and Indian nationalist who was educated in the West, formulated a synthesis of evolutionary thought and Hinduism. He interpreted the classic avatara doctrine, according to which God incarnates into the world repeatedly throughout time, in evolutionary terms. God thus appears first as an animal, later as a dwarf, then as a violent man (Rama), and then as Buddha, and as Kṛṣṇa. He proposed a metaphysical picture where both spiritual evolution (reincarnation and avatars) and physical evolution are ultimately a manifestation of God (Brahman). This view of reality as consisting of matter ( prakṛti ) and consciousness ( puruṣa ) goes back to sāṃkhya , one of the orthodox Hindu darśana, but Aurobindo made explicit reference to the divine, calling the process during which the supreme Consciousness dwells in matter involution (Aurobindo, 1914–18 [2005], see C.M. Brown 2007 for discussion).

During the twentieth century, Indian scientists began to gain prominence, including C.V. Raman (1888–1970), a Nobel Prize winner in physics, and Satyendra Nath Bose (1894–1974), a theoretical physicist who described the behavior of photons statistically, and who gave his name to bosons. However, these authors were silent on the relationship between their scientific work and their religious beliefs. By contrast, the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920) was open about his religious beliefs and their influence on his mathematical work. He claimed that the goddess Namagiri helped him to intuit solutions to mathematical problems. Likewise, Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858–1937), a theoretical physicist, biologist, biophysicist, botanist, and archaeologist who worked on radio waves, saw the Hindu idea of unity reflected in the study of nature. He started the Bose institute in Kolkata in 1917, the earliest interdisciplinary scientific institute in India (Subbarayappa 2011).

Buddhism, like the other religious traditions surveyed in this entry, encompasses many views and practices. The principal forms of Buddhism that exist today are Theravāda and Mahāyāna. (Vajrayāna, the tantric tradition of Buddhism, is also sometimes seen as a distinct form.) Theravāda is the dominant form of Buddhism of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. It traditionally refers to monastic and textual lineages associated with the study of the Pāli Buddhist Canon. Mahāyāna refers to a movement that likely began roughly four centuries after the Buddha’s death; it became the dominant form of Buddhism in East and Central Asia. It includes Chan or Zen, and also tantric Buddhism, which today is found mostly in Tibet, though East Asian forms also exist.

Buddhism originated in the historical figure of the Buddha (historically, Gautama Buddha or Siddhārtha Gautama, ca. 5 th –4 th century BCE). His teaching centered on ethics as well as metaphysics, incapsulated in the Four Noble Truths (on suffering and its origin in human desires), and the Noble Eightfold Path (right view, right aspiration, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration) to end suffering and to break the cycle of rebirths, culminating in reaching Nirvana. Substantive metaphysical teachings include belief in karma, the no-self, and the cycle of rebirth.

As a response to colonialist attitudes, modern Buddhists since the nineteenth century have often presented Buddhism as harmonious with science (Lopez 2008). The argument is roughly that since Buddhism doesn’t require belief in metaphysically substantive entities such as God, the soul, or the self (unlike, for example, Christianity), Buddhism should be easily compatible with the factual claims that scientists make. (Note, however, that historically most Buddhist have believed in various forms of divine abode and divinities.) We could thus expect the dialogue and integration view to prevail in Buddhism. An exemplar for integration is the fourteenth Dalai Lama, who is known for his numerous efforts to lead dialogue between religious people and scientists. He has extensively written on the relationship between Buddhism and various scientific disciplines such as neuroscience and cosmology (e.g., Dalai Lama 2005, see also the Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics series, a four-volume series conceived and compiled by the Dalai Lama, e.g., Jinpa 2017). Donald Lopez Jr (2008) identifies compatibility as an enduring claim in the debate on science and Buddhism, in spite of the fact that what is meant by these concepts has shifted markedly over time. As David McMahan (2009) argues, Buddhism underwent profound shifts in response to modernity in the west as well as globally. In this modern context, Buddhists have often asserted the compatibility of Buddhism with science, favorably contrasting their religion to Christianity in that respect.

The full picture of the relationship between Buddhism and religion is more nuanced than one of wholesale acceptance of scientific claims. I will here focus on East Asia, primarily Japan and China, and the reception of evolutionary theory in the early twentieth century to give a sense of this more complex picture. The earliest translations of evolutionary thought in Japan and China were not drawn from Darwin’s Origin of Species or Descent of Man , but from works by authors who worked in Darwin’s wake, such as Ernst Haeckel and Thomas Huxley. For example, the earliest translated writings on evolutionary theory in China was a compilation by Yan Fu entitled On Natural Evolution ( Tianyan lun ), which incorporated excerpts by Herbert Spencer and Thomas Huxley. This work drew a close distinction between social Darwinism and biological evolution (Ritzinger 2013). Chinese and Japanese Buddhists received these ideas in the context of western colonialism and imperialism. East Asian intellectuals saw how western colonial powers competed with each other for influence on their territory, and discerned parallels between this and the Darwinian struggle for existence. As a result, some intellectuals such as the Japanese political adviser and academic Katō Hiroyuki (1836–1916) drew on Darwinian thought and popularized notions such as “survival of the fittest” to justify the foreign policies of the Meiji government (Burenina 2020). It is in this context that we can situate Buddhist responses to evolutionary theory.

Buddhists do not distinguish between human beings as possessing a soul and other animals as soulless. As we are all part of the cycle of rebirth, we have all been in previous lives various other beings, including birds, insects, and fish. The problem of the specificity of the human soul does not even arise because of the no-self doctrine. Nevertheless, as Justin Ritzinger (2013) points out, Chinese Buddhists in the 1920s and 1930s who were confronted with early evolutionary theory did not accept Darwin’s theory wholesale. In their view, the central element of Darwinism—the struggle for existence—was incompatible with Buddhism, with its emphasis on compassion with other creatures. They rejected social Darwinism (which sought to engineer societies along Darwinian principles) because it was incompatible with Buddhist ethics and metaphysics. Struggling to survive and to propagate was clinging onto worldly things. Taixu (1890–1947), a Chinese Reformer and Buddhist modernist, instead chose to appropriate Pyotr Kropotkin’s evolutionary views, specifically on mutual aid and altruism. The Russian anarchist argued that cooperation was central to evolutionary change, a view that is currently also more mainstream. However, Kropotkin’s view did not go far enough in Taixu’s opinion because mutual aid still requires a self. Only when one recognizes the no-self doctrine could one dedicate oneself entirely to helping others, as bodhisattvas do (Ritzinger 2013).

Similar dynamics can be seen in the reception of evolutionary theory among Japanese Buddhists. Evolutionary theory was introduced in Japan during the early Meji period (1868–1912) when Japan opened itself to foreign trade and ideas. Foreign experts, such as the American zoologist Edward S. Morse (1838–1925) shared their knowledge of the sciences with Japanese scholars. The latter were interested in the social ramifications of Darwinism, particularly because they had access to translated versions of Spencer’s and Huxley’s work before they could read Darwin’s. Japanese Buddhists of the Nichiren tradition accepted many elements of evolutionary theory, but they rejected other elements, notably the struggle for existence, and randomness and chance, as this contradicts the role of karma in one’s circumstances at birth.

Among the advocates of the modern Nishiren Buddhist movement is Honda Nisshō (1867–1931). Honda emphasized the importance of retrogressions (in addition to progress, which was the main element in evolution that western authors such as Haeckel and Spencer considered). He strongly argued against social Darwinism, the application of evolutionary principles in social engineering, on religious grounds. He argued that we can accept humans are descended from apes without having to posit a pessimistic view of human nature that sees us as engaged in a struggle for survival with fellow human beings. Like Chinese Buddhists, Honda thought Kropotkin’s thesis of mutual aid was more compatible with Buddhism, but he was suspicious of Kropotkin’s anarchism (Burenina 2020). His work, like that of other East Asian Buddhists indicates that historically, Buddhists are not passive recipients of western science but creative interpreters. In some cases, their religious reasons for rejecting some metaphysical assumptions in evolutionary theory led them to anticipate recent developments in biology, such as the recognition of cooperation as an evolutionary principle.

Judaism is one of the three major Abrahamic monotheistic traditions, encompassing a range of beliefs and practices that express a covenant between God and the people of Israel. Central to both Jewish practice and beliefs is the study of texts, including the written Torah (the Tanakh, sometimes called “Hebrew Bible”), and the “Oral Law” of Rabbinic Judaism, compiled in such works like the Talmud. There is also a corpus of esoteric, mystical interpretations of biblical texts, the Kabbalah, which has influenced Jewish works on the relationship between science and religion. The Kabbalah also had an influence on Renaissance and early modern Christian authors such as Pico Della Mirandola, whose work helped to shape the scientific revolution (see the entry on Giovanni Pico della Mirandola ). The theologian Maimonides (Rabbi Moshe ben-Maimon, 1138–1204, aka Rambam) had an enduring influence on Jewish thought up until today, also in the science and religion literature.

Most contemporary strains of Judaism are Rabbinic, rather than biblical, and this has profound implications for the relationship between religion and science. While both Jews and Evangelical Christians emphasize the reading of sacred texts, the Rabbinic traditions (unlike, for example, the Evangelical Christian tradition) holds that reading and interpreting texts is far from straightforward. Scripture should not be read in a simple literal fashion. This opens up more space for accepting scientific theories (e.g., Big Bang cosmology) that seem at odds with a simple literal reading of the Torah (e.g., the six-day creation in Genesis) (Mitelman 2011 [ Other Internet Resources ]). Moreover, most non-Orthodox Jews in the US identify as politically liberal, so openness to science may also be an identity marker given that politically liberal people in the US have positive attitudes toward science (Pew Forum, 2021 [ Other Internet Resources ]).

Jewish thinkers have made substantive theoretical contributions to the relationship between science and religion, which differ in interesting respects from those seen in the literature written by Christian authors. To give just a few examples, Hermann Cohen (1842–1918), a prominent neo-Kantian German Jewish philosopher, thought of the relationship between Judaism and science in the light of the advances in scientific disciplines and the increased participation of Jewish scholars in the sciences. He argued that science, ethics, and Judaism should all be conceived of as distinct but complementary sciences. Cohen believed that his Jewish religious community was facing an epistemic crisis. All references to God had become suspect due to an adherence to naturalism, at first epistemological, but fast becoming ontological. Cohen saw the concept of a transcendent God as foundational to both Jewish practice and belief, so he thought adherence to wholesale naturalism threatened both Jewish orthodoxy and orthopraxy. As Teri Merrick (2020) argues, Cohen suspected this was in part due to epistemic oppression and self-censuring (though Cohen did not frame it in these terms). Because Jewish scientists wanted to retain credibility in the Christian majority culture, they underplayed and neglected the rich Jewish intellectual legacy in their practice. In response to this intellectual crisis, Cohen proposed to reframe Jewish thought and philosophy so that it would be recognized as both continuous with the tradition and essentially contributing to ethical and scientific advances. In this way, he reframed this tradition, articulating a broadly Kantian philosophy of science to combat a perceived conflict between Judaism and science (see the entry on Hermann Cohen for an in-depth discussion).

Jewish religious scholars have examined how science might influence religious beliefs, and vice versa. Rather than a unified response we see a spectrum of philosophical views, especially since the nineteenth and early twentieth century. As Shai Cherry (2003) surveys, Jewish scholars in the early twentieth century accepted biological evolution but were hesitant about Darwinian natural selection as the mechanism. The Latvian-born Israeli rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865–1935) thought that religion and science are largely separate domains (a view somewhat similar to Gould’s NOMA), though he believed that there was a possible flow from religion to science. For example, Kook challenged the lack of directionality in Darwinian evolutionary theory. Using readings of the Kabbalah (and Halakhah, Jewish law), he proposed that biological evolution fits in a larger picture of cosmic evolution towards perfection.

By contrast, the American rabbi Morcedai Kaplan (1881–1983) thought information flow between science and religion could go in both directions, a view reminiscent to Barbour’s dialogue position. He repeatedly argued against scientism (the encroachment of science on too many aspects of human life, including ethics and religion), but he believed nevertheless we ought to apply scientific methods to religion. He saw reality as an unfolding process without a pre-ordained goal: it was progressive, but not teleologically determined. Kaplan emphasized the importance of morality (and identified God as the source of this process), and conceptualized humanity as not merely a passive recipient of evolutionary change, but an active participant, prefiguring work in evolutionary biology on the importance of agency in evolution (e.g., Okasha 2018). Thus, Kaplan’s reception of scientific theories, especially evolution, led him to formulate an early Jewish process theology.

Reform Judaism endorses an explicit anti-conflict view on the relationship between science and religion. For example, the Pittsburgh Platform of 1885, the first document of the Reform rabbinate, has a statement that explicitly says that science and Judaism are not in conflict:

We hold that the modern discoveries of scientific researches in the domain of nature and history are not antagonistic to the doctrines of Judaism.

This Platform had an enduring influence on Reform Judaism over the next decades. Secular Jewish scientists such as Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Douglas Daniel Kahneman, and Stephen J. Gould have also reflected on the relationship between science and broader issues of existential significance, and have exerted considerable influence on the science and religion debate.

3. Central topics in the debate

Current work in the field of science and religion encompasses a wealth of topics, including free will, ethics, human nature, and consciousness. Contemporary natural theologians discuss fine-tuning, in particular design arguments based on it (e.g., R. Collins 2009), the interpretation of multiverse cosmology, and the significance of the Big Bang (see entries on fine-tuning arguments and natural theology and natural religion ). For instance, authors such as Hud Hudson (2013) have explored the idea that God has actualized the best of all possible multiverses. Here follows an overview of two topics that continue to generate substantial interest and debate: divine action (and the closely related topic of creation) and human origins. The focus will be on Christian work in science and religion, due to its prevalence in the literature.

Before scientists developed their views on cosmology and origins of the world, Western cultures already had a doctrine of creation, based on biblical texts (e.g., the first three chapters of Genesis and the book of Revelation) and the writings of church fathers such as Augustine. This doctrine of creation has the following interrelated features: first, God created the world ex nihilo, i.e., out of nothing. Differently put, God did not need any pre-existing materials to make the world, unlike, e.g., the Demiurge (from Greek philosophy), who created the world from chaotic, pre-existing matter. Second, God is distinct from the world; the world is not equal to or part of God (contra pantheism or panentheism) or a (necessary) emanation of God’s being (contra Neoplatonism). Rather, God created the world freely. This introduces an asymmetry between creator and creature: the world is radically contingent upon God’s creative act and is also sustained by God, whereas God does not need creation (Jaeger 2012b: 3). Third, the doctrine of creation holds that creation is essentially good (this is repeatedly affirmed in Genesis 1). The world does contain evil, but God does not directly cause this evil to exist. Moreover, God does not merely passively sustain creation, but rather plays an active role in it, using special divine actions (e.g., miracles and revelations) to care for creatures. Fourth, God made provisions for the end of the world, and will create a new heaven and earth, in this way eradicating evil.

Views on divine action are related to the doctrine of creation. Theologians commonly draw a distinction between general and special divine action, but within the field of science and religion there is no universally accepted definition of these two concepts. One way to distinguish them (Wildman 2008: 140) is to regard general divine action as the creation and sustenance of reality, and special divine action as the collection of specific providential acts, such as miracles and revelations to prophets. Drawing this distinction allows for creatures to be autonomous and indicates that God does not micromanage every detail of creation. Still, the distinction is not always clear-cut, as some phenomena are difficult to classify as either general or special divine action. For example, the Roman Catholic Eucharist (in which bread and wine become the body and blood of Jesus) or some healing miracles outside of scripture seem mundane enough to be part of general housekeeping (general divine action), but still seem to involve some form of special intervention on God’s part. Alston (1989) makes a related distinction between direct and indirect divine acts. God brings about direct acts without the use of natural causes, whereas indirect acts are achieved through natural causes. Using this distinction, there are four possible kinds of actions that God could do: God could not act in the world at all, God could act only directly, God could act only indirectly, or God could act both directly and indirectly.

In the science and religion literature, there are two central questions on creation and divine action. To what extent are the Christian doctrine of creation and traditional views of divine action compatible with science? How can these concepts be understood within a scientific context, e.g., what does it mean for God to create and act? Note that the doctrine of creation says nothing about the age of the Earth, nor does it specify a mode of creation. This allows for a wide range of possible views within science and religion, of which Young Earth creationism is but one that is consistent with scripture. Indeed, some scientific theories, such as the Big Bang theory, first proposed by the Belgian Roman Catholic priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître (1927), look congenial to the doctrine of creation. The theory is not in contradiction, and could be integrated into creatio ex nihilo as it specifies that the universe originated from an extremely hot and dense state around 13.8 billion years ago (Craig 2003), although some philosophers have argued against the interpretation that the universe has a temporal beginning (e.g., Pitts 2008).

The net result of scientific findings since the seventeenth century has been that God was increasingly pushed into the margins. This encroachment of science on the territory of religion happened in two ways: first, scientific findings—in particular from geology and evolutionary theory—challenged and replaced biblical accounts of creation. Although the doctrine of creation does not contain details of the mode and timing of creation, the Bible was regarded as authoritative, and that authority got eroded by the sciences. Second, the emerging concept of scientific laws in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century physics seemed to leave no room for special divine action. These two challenges will be discussed below, along with proposed solutions in the contemporary science and religion literature.

Christian authors have traditionally used the Bible as a source of historical information. Biblical exegesis of the creation narratives, especially Genesis 1 and 2 (and some other scattered passages, such as in the Book of Job), remains fraught with difficulties. Are these texts to be interpreted in a historical, metaphorical, or poetic fashion, and what are we to make of the fact that the order of creation differs between these accounts (Harris 2013)? The Anglican archbishop James Ussher (1581–1656) used the Bible to date the beginning of creation at 4004 BCE. Although such literalist interpretations of the biblical creation narratives were not uncommon, and are still used by Young Earth creationists today, theologians before Ussher already offered alternative, non-literalist readings of the biblical materials (e.g., Augustine De Genesi ad litteram , 416). From the seventeenth century onward, the Christian doctrine of creation came under pressure from geology, with findings suggesting that the Earth was significantly older than 4004 BCE. From the eighteenth century on, natural philosophers, such as Benoît de Maillet, Lamarck, Chambers, and Darwin, proposed transmutationist (what would now be called evolutionary) theories, which seem incompatible with scriptural interpretations of the special creation of species. Following the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), there has been an ongoing discussion on how to reinterpret the doctrine of creation in the light of evolutionary theory (see Bowler 2009 for an overview).