Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 281–288, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Erin S. Barry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0788-7153 1 , 2 ,

- Jerusalem Merkebu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3707-8920 3 &

- Lara Varpio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1412-4341 3

32k Accesses

25 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Introduction

Researchers and practitioners rely on literature reviews to synthesize large bodies of knowledge. Many types of literature reviews have been developed, each targeting a specific purpose. However, these syntheses are hampered if the review type’s paradigmatic roots, methods, and markers of rigor are only vaguely understood. One literature review type whose methodology has yet to be elucidated is the state-of-the-art (SotA) review. If medical educators are to harness SotA reviews to generate knowledge syntheses, we must understand and articulate the paradigmatic roots of, and methods for, conducting SotA reviews.

We reviewed 940 articles published between 2014–2021 labeled as SotA reviews. We (a) identified all SotA methods-related resources, (b) examined the foundational principles and techniques underpinning the reviews, and (c) combined our findings to inductively analyze and articulate the philosophical foundations, process steps, and markers of rigor.

In the 940 articles reviewed, nearly all manuscripts (98%) lacked citations for how to conduct a SotA review. The term “state of the art” was used in 4 different ways. Analysis revealed that SotA articles are grounded in relativism and subjectivism.

This article provides a 6-step approach for conducting SotA reviews. SotA reviews offer an interpretive synthesis that describes: This is where we are now. This is how we got here. This is where we could be going. This chronologically rooted narrative synthesis provides a methodology for reviewing large bodies of literature to explore why and how our current knowledge has developed and to offer new research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

An analysis of current practices in undertaking literature reviews in nursing: findings from a focused mapping review and synthesis

Reviewing the literature, how systematic is systematic.

Reading and interpreting reviews for health professionals: a practical review

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Literature reviews play a foundational role in scientific research; they support knowledge advancement by collecting, describing, analyzing, and integrating large bodies of information and data [ 1 , 2 ]. Indeed, as Snyder [ 3 ] argues, all scientific disciplines require literature reviews grounded in a methodology that is accurate and clearly reported. Many types of literature reviews have been developed, each with a unique purpose, distinct methods, and distinguishing characteristics of quality and rigor [ 4 , 5 ].

Each review type offers valuable insights if rigorously conducted [ 3 , 6 ]. Problematically, this is not consistently the case, and the consequences can be dire. Medical education’s policy makers and institutional leaders rely on knowledge syntheses to inform decision making [ 7 ]. Medical education curricula are shaped by these syntheses. Our accreditation standards are informed by these integrations. Our patient care is guided by these knowledge consolidations [ 8 ]. Clearly, it is important for knowledge syntheses to be held to the highest standards of rigor. And yet, that standard is not always maintained. Sometimes scholars fail to meet the review’s specified standards of rigor; other times the markers of rigor have never been explicitly articulated. While we can do little about the former, we can address the latter. One popular literature review type whose methodology has yet to be fully described, vetted, and justified is the state-of-the-art (SotA) review.

While many types of literature reviews amalgamate bodies of literature, SotA reviews offer something unique. By looking across the historical development of a body of knowledge, SotA reviews delves into questions like: Why did our knowledge evolve in this way? What other directions might our investigations have taken? What turning points in our thinking should we revisit to gain new insights? A SotA review—a form of narrative knowledge synthesis [ 5 , 9 ]—acknowledges that history reflects a series of decisions and then asks what different decisions might have been made.

SotA reviews are frequently used in many fields including the biomedical sciences [ 10 , 11 ], medicine [ 12 , 13 , 14 ], and engineering [ 15 , 16 ]. However, SotA reviews are rarely seen in medical education; indeed, a bibliometrics analysis of literature reviews published in 14 core medical education journals between 1999 and 2019 reported only 5 SotA reviews out of the 963 knowledge syntheses identified [ 17 ]. This is not to say that SotA reviews are absent; we suggest that they are often unlabeled. For instance, Schuwirth and van der Vleuten’s article “A history of assessment in medical education” [ 14 ] offers a temporally organized overview of the field’s evolving thinking about assessment. Similarly, McGaghie et al. published a chronologically structured review of simulation-based medical education research that “reviews and critically evaluates historical and contemporary research on simulation-based medical education” [ 18 , p. 50]. SotA reviews certainly have a place in medical education, even if that place is not explicitly signaled.

This lack of labeling is problematic since it conceals the purpose of, and work involved in, the SotA review synthesis. In a SotA review, the author(s) collects and analyzes the historical development of a field’s knowledge about a phenomenon, deconstructs how that understanding evolved, questions why it unfolded in specific ways, and posits new directions for research. Senior medical education scholars use SotA reviews to share their insights based on decades of work on a topic [ 14 , 18 ]; their junior counterparts use them to critique that history and propose new directions [ 19 ]. And yet, SotA reviews are generally not explicitly signaled in medical education. We suggest that at least two factors contribute to this problem. First, it may be that medical education scholars have yet to fully grasp the unique contributions SotA reviews provide. Second, the methodology and methods of SotA reviews are poorly reported making this form of knowledge synthesis appear to lack rigor. Both factors are rooted in the same foundational problem: insufficient clarity about SotA reviews. In this study, we describe SotA review methodology so that medical educators can explicitly use this form of knowledge synthesis to further advance the field.

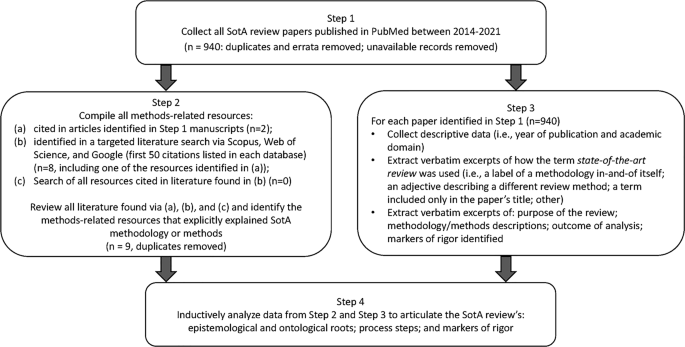

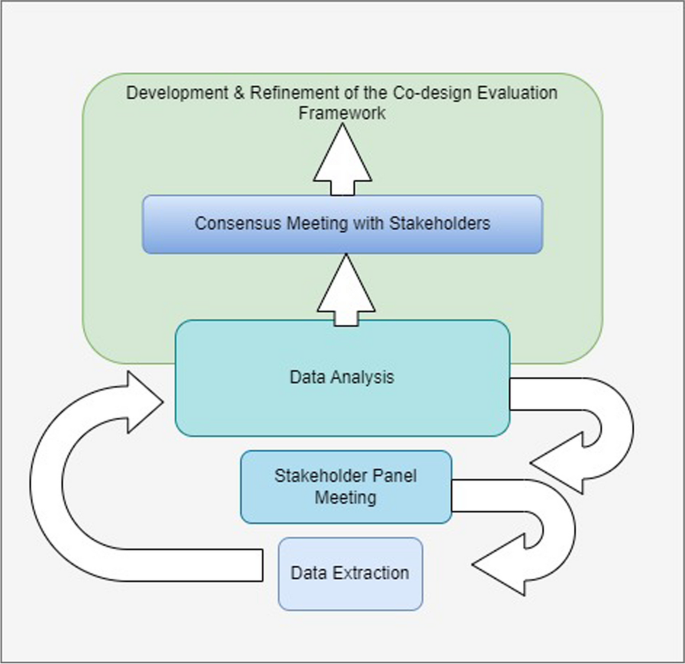

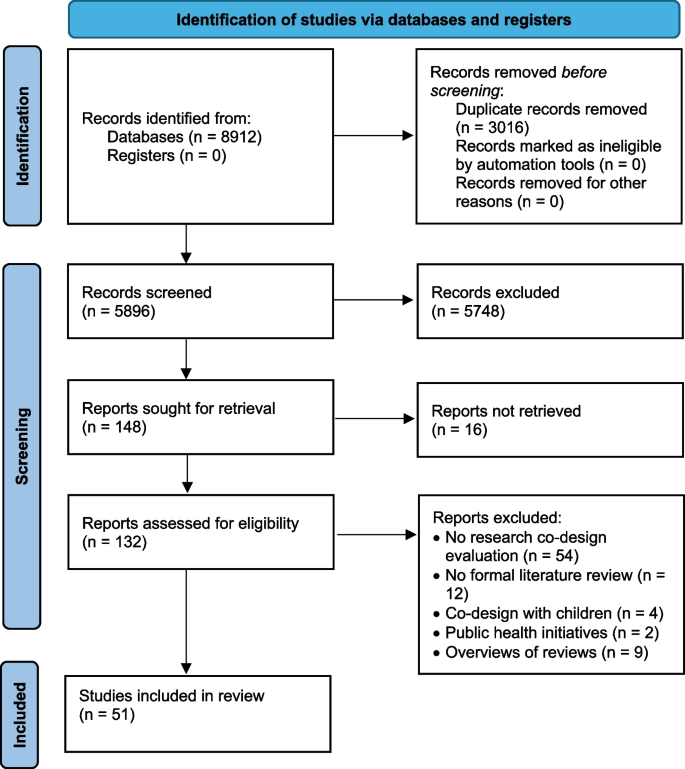

We developed a four-step research design to meet this goal, illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Four-step research design process used for developing a State-of-the-Art literature review methodology

Step 1: Collect SotA articles

To build our initial corpus of articles reporting SotA reviews, we searched PubMed using the strategy (″state of the art review″[ti] OR ″state of the art review*″) and limiting our search to English articles published between 2014 and 2021. We strategically focused on PubMed, which includes MEDLINE, and is considered the National Library of Medicine’s premier database of biomedical literature and indexes health professions education and practice literature [ 20 ]. We limited our search to 2014–2021 to capture modern use of SotA reviews. Of the 960 articles identified, nine were excluded because they were duplicates, erratum, or corrigendum records; full text copies were unavailable for 11 records. All articles identified ( n = 940) constituted the corpus for analysis.

Step 2: Compile all methods-related resources

EB, JM, or LV independently reviewed the 940 full-text articles to identify all references to resources that explained, informed, described, or otherwise supported the methods used for conducting the SotA review. Articles that met our criteria were obtained for analysis.

To ensure comprehensive retrieval, we also searched Scopus and Web of Science. Additionally, to find resources not indexed by these academic databases, we searched Google (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] for the search strategies used for each database). EB also reviewed the first 50 items retrieved from each search looking for additional relevant resources. None were identified. Via these strategies, nine articles were identified and added to the collection of methods-related resources for analysis.

Step 3: Extract data for analysis

In Step 3, we extracted three kinds of information from the 940 articles papers identified in Step 1. First, descriptive data on each article were compiled (i.e., year of publication and the academic domain targeted by the journal). Second, each article was examined and excerpts collected about how the term state-of-the-art review was used (i.e., as a label for a methodology in-and-of itself; as an adjective qualifying another type of literature review; as a term included in the paper’s title only; or in some other way). Finally, we extracted excerpts describing: the purposes and/or aims of the SotA review; the methodology informing and methods processes used to carry out the SotA review; outcomes of analyses; and markers of rigor for the SotA review.

Two researchers (EB and JM) coded 69 articles and an interrater reliability of 94.2% was achieved. Any discrepancies were discussed. Given the high interrater reliability, the two authors split the remaining articles and coded independently.

Step 4: Construct the SotA review methodology

The methods-related resources identified in Step 2 and the data extractions from Step 3 were inductively analyzed by LV and EB to identify statements and research processes that revealed the ontology (i.e., the nature of reality that was reflected) and the epistemology (i.e., the nature of knowledge) underpinning the descriptions of the reviews. These authors studied these data to determine if the synthesis adhered to an objectivist or a subjectivist orientation, and to synthesize the purposes realized in these papers.

To confirm these interpretations, LV and EB compared their ontology, epistemology, and purpose determinations against two expectations commonly required of objectivist synthesis methods (e.g., systematic reviews): an exhaustive search strategy and an appraisal of the quality of the research data. These expectations were considered indicators of a realist ontology and objectivist epistemology [ 21 ] (i.e., that a single correct understanding of the topic can be sought through objective data collection {e.g., systematic reviews [ 22 ]}). Conversely, the inverse of these expectations were considered indicators of a relativist ontology and subjectivist epistemology [ 21 ] (i.e., that no single correct understanding of the topic is available; there are multiple valid understandings that can be generated and so a subjective interpretation of the literature is sought {e.g., narrative reviews [ 9 ]}).

Once these interpretations were confirmed, LV and EB reviewed and consolidated the methods steps described in these data. Markers of rigor were then developed that aligned with the ontology, epistemology, and methods of SotA reviews.

Of the 940 articles identified in Step 1, 98% ( n = 923) lacked citations or other references to resources that explained, informed, or otherwise supported the SotA review process. Of the 17 articles that included supporting information, 16 cited Grant and Booth’s description [ 4 ] consisting of five sentences describing the overall purpose of SotA reviews, three sentences noting perceived strengths, and four sentences articulating perceived weaknesses. This resource provides no guidance on how to conduct a SotA review methodology nor markers of rigor. The one article not referencing Grant and Booth used “an adapted comparative effectiveness research search strategy that was adapted by a health sciences librarian” [ 23 , p. 381]. One website citation was listed in support of this strategy; however, the page was no longer available in summer 2021. We determined that the corpus was uninformed by a cardinal resource or a publicly available methodology description.

In Step 2 we identified nine resources [ 4 , 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]; none described the methodology and/or processes of carrying out SotA reviews. Nor did they offer explicit descriptions of the ontology or epistemology underpinning SotA reviews. Instead, these resources provided short overview statements (none longer than one paragraph) about the review type [ 4 , 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Thus, we determined that, to date, there are no available methodology papers describing how to conduct a SotA review.

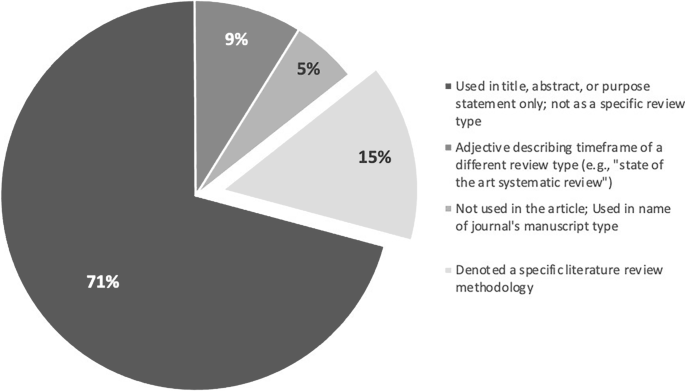

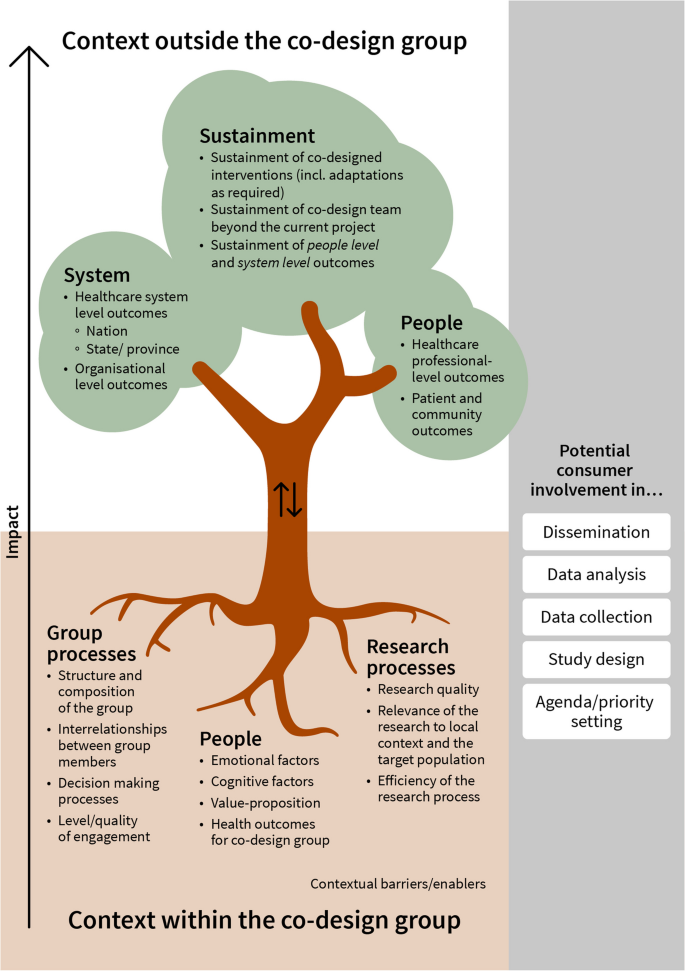

Step 3 revealed that “state of the art” was used in 4 different ways across the 940 articles (see Fig. 2 for the frequency with which each was used). In 71% ( n = 665 articles), the phrase was used only in the title, abstract, and/or purpose statement of the article; the phrase did not appear elsewhere in the paper and no SotA methodology was discussed. Nine percent ( n = 84) used the phrase as an adjective to qualify another literature review type and so relied entirely on the methodology of a different knowledge synthesis approach (e.g., “a state of the art systematic review [ 29 ]”). In 5% ( n = 52) of the articles, the phrase was not used anywhere within the article; instead, “state of the art” was the type of article within a journal. In the remaining 15% ( n = 139), the phrase denoted a specific methodology (see ESM for all methodology articles). Via Step 4’s inductive analysis, the following foundational principles of SotA reviews were developed: (1) the ontology, (2) epistemology, and (3) purpose of SotA reviews.

Four ways the term “state of the art” is used in the corpus and how frequently each is used

Ontology of SotA reviews: Relativism

SotA reviews rest on four propositions:

The literature addressing a phenomenon offers multiple perspectives on that topic (i.e., different groups of researchers may hold differing opinions and/or interpretations of data about a phenomenon).

The reality of the phenomenon itself cannot be completely perceived or understood (i.e., due to limitations [e.g., the capabilities of current technologies, a research team’s disciplinary orientation] we can only perceive a limited part of the phenomenon).

The reality of the phenomenon is a subjective and inter-subjective construction (i.e., what we understand about a phenomenon is built by individuals and so their individual subjectivities shape that understanding).

The context in which the review was conducted informs the review (e.g., a SotA review of literature about gender identity and sexual function will be synthesized differently by researchers in the domain of gender studies than by scholars working in sex reassignment surgery).

As these propositions suggest, SotA scholars bring their experiences, expectations, research purposes, and social (including academic) orientations to bear on the synthesis work. In other words, a SotA review synthesizes the literature based on a specific orientation to the topic being addressed. For instance, a SotA review written by senior scholars who are experts in the field of medical education may reflect on the turning points that have shaped the way our field has evolved the modern practices of learner assessment, noting how the nature of the problem of assessment has moved: it was first a measurement problem, then a problem that embraced human judgment but needed assessment expertise, and now a whole system problem that is to be addressed from an integrated—not a reductionist—perspective [ 12 ]. However, if other scholars were to examine this same history from a technological orientation, learner assessment could be framed as historically constricted by the media available through which to conduct assessment, pointing to how artificial intelligence is laying the foundation for the next wave of assessment in medical education [ 30 ].

Given these foundational propositions, SotA reviews are steeped in a relativist ontology—i.e., reality is socially and experientially informed and constructed, and so no single objective truth exists. Researchers’ interpretations reflect their conceptualization of the literature—a conceptualization that could change over time and that could conflict with the understandings of others.

Epistemology of SotA reviews: Subjectivism

SotA reviews embrace subjectivism. The knowledge generated through the review is value-dependent, growing out of the subjective interpretations of the researcher(s) who conducted the synthesis. The SotA review generates an interpretation of the data that is informed by the expertise, experiences, and social contexts of the researcher(s). Furthermore, the knowledge developed through SotA reviews is shaped by the historical point in time when the review was conducted. SotA reviews are thus steeped in the perspective that knowledge is shaped by individuals and their community, and is a synthesis that will change over time.

Purpose of SotA reviews

SotA reviews create a subjectively informed summary of modern thinking about a topic. As a chronologically ordered synthesis, SotA reviews describe the history of turning points in researchers’ understanding of a phenomenon to contextualize a description of modern scientific thinking on the topic. The review presents an argument about how the literature could be interpreted; it is not a definitive statement about how the literature should or must be interpreted. A SotA review explores: the pivotal points shaping the historical development of a topic, the factors that informed those changes in understanding, and the ways of thinking about and studying the topic that could inform the generation of further insights. In other words, the purpose of SotA reviews is to create a three-part argument: This is where we are now in our understanding of this topic. This is how we got here. This is where we could go next.

The SotA methodology

Based on study findings and analyses, we constructed a six-stage SotA review methodology. This six-stage approach is summarized and guiding questions are offered in Tab. 1 .

Stage 1: Determine initial research question and field of inquiry

In Stage 1, the researcher(s) creates an initial description of the topic to be summarized and so must determine what field of knowledge (and/or practice) the search will address. Knowledge developed through the SotA review process is shaped by the context informing it; thus, knowing the domain in which the review will be conducted is part of the review’s foundational work.

Stage 2: Determine timeframe

This stage involves determining the period of time that will be defined as SotA for the topic being summarized. The researcher(s) should engage in a broad-scope overview of the literature, reading across the range of literature available to develop insights into the historical development of knowledge on the topic, including the turning points that shape the current ways of thinking about a topic. Understanding the full body of literature is required to decide the dates or events that demarcate the timeframe of now in the first of the SotA’s three-part argument: where we are now . Stage 2 is complete when the researcher(s) can explicitly justify why a specific year or event is the right moment to mark the beginning of state-of-the-art thinking about the topic being summarized.

Stage 3: Finalize research question(s) to reflect timeframe

Based on the insights developed in Stage 2, the researcher(s) will likely need to revise their initial description of the topic to be summarized. The formal research question(s) framing the SotA review are finalized in Stage 3. The revised description of the topic, the research question(s), and the justification for the timeline start year must be reported in the review article. These are markers of rigor and prerequisites for moving to Stage 4.

Stage 4: Develop search strategy to find relevant articles

In Stage 4, the researcher(s) develops a search strategy to identify the literature that will be included in the SotA review. The researcher(s) needs to determine which literature databases contain articles from the domain of interest. Because the review describes how we got here , the review must include literature that predates the state-of-the-art timeframe, determined in Stage 2, to offer this historical perspective.

Developing the search strategy will be an iterative process of testing and revising the search strategy to enable the researcher(s) to capture the breadth of literature required to meet the SotA review purposes. A librarian should be consulted since their expertise can expedite the search processes and ensure that relevant resources are identified. The search strategy must be reported (e.g., in the manuscript itself or in a supplemental file) so that others may replicate the process if they so choose (e.g., to construct a different SotA review [and possible different interpretations] of the same literature). This too is a marker of rigor for SotA reviews: the search strategies informing the identification of literature must be reported.

Stage 5: Analyses

The literature analysis undertaken will reflect the subjective insights of the researcher(s); however, the foundational premises of inductive research should inform the analysis process. Therefore, the researcher(s) should begin by reading the articles in the corpus to become familiar with the literature. This familiarization work includes: noting similarities across articles, observing ways-of-thinking that have shaped current understandings of the topic, remarking on assumptions underpinning changes in understandings, identifying important decision points in the evolution of understanding, and taking notice of gaps and assumptions in current knowledge.

The researcher(s) can then generate premises for the state-of-the-art understanding of the history that gave rise to modern thinking, of the current body of knowledge, and of potential future directions for research. In this stage of the analysis, the researcher(s) should document the articles that support or contradict their premises, noting any collections of authors or schools of thinking that have dominated the literature, searching for marginalized points of view, and studying the factors that contributed to the dominance of particular ways of thinking. The researcher(s) should also observe historical decision points that could be revisited. Theory can be incorporated at this stage to help shape insights and understandings. It should be highlighted that not all corpus articles will be used in the SotA review; instead, the researcher(s) will sample across the corpus to construct a timeline that represents the seminal moments of the historical development of knowledge.

Next, the researcher(s) should verify the thoroughness and strength of their interpretations. To do this, the researcher(s) can select different articles included in the corpus and examine if those articles reflect the premises the researcher(s) set out. The researcher(s) may also seek out contradictory interpretations in the literature to be sure their summary refutes these positions. The goal of this verification work is not to engage in a triangulation process to ensure objectivity; instead, this process helps the researcher(s) ensure the interpretations made in the SotA review represent the articles being synthesized and respond to the interpretations offered by others. This is another marker of rigor for SotA reviews: the authors should engage in and report how they considered and accounted for differing interpretations of the literature, and how they verified the thoroughness of their interpretations.

Stage 6: Reflexivity

Given the relativist subjectivism of a SotA review, it is important that the manuscript offer insights into the subjectivity of the researcher(s). This reflexivity description should articulate how the subjectivity of the researcher(s) informed interpretations of the data. These reflections will also influence the suggested directions offered in the last part of the SotA three-part argument: where we could go next. This is the last marker of rigor for SotA reviews: researcher reflexivity must be considered and reported.

SotA reviews have much to offer our field since they provide information on the historical progression of medical education’s understanding of a topic, the turning points that guided that understanding, and the potential next directions for future research. Those future directions may question the soundness of turning points and prior decisions, and thereby offer new paths of investigation. Since we were unable to find a description of the SotA review methodology, we inductively developed a description of the methodology—including its paradigmatic roots, the processes to be followed, and the markers of rigor—so that scholars can harness the unique affordances of this type of knowledge synthesis.

Given their chronology- and turning point-based orientation, SotA reviews are inherently different from other types of knowledge synthesis. For example, systematic reviews focus on specific research questions that are narrow in scope [ 32 , 33 ]; in contrast, SotA reviews present a broader historical overview of knowledge development and the decisions that gave rise to our modern understandings. Scoping reviews focus on mapping the present state of knowledge about a phenomenon including, for example, the data that are currently available, the nature of that data, and the gaps in knowledge [ 34 , 35 ]; conversely, SotA reviews offer interpretations of the historical progression of knowledge relating to a phenomenon centered on significant shifts that occurred during that history. SotA reviews focus on the turning points in the history of knowledge development to suggest how different decisions could give rise to new insights. Critical reviews draw on literature outside of the domain of focus to see if external literature can offer new ways of thinking about the phenomenon of interest (e.g., drawing on insights from insects’ swarm intelligence to better understand healthcare team adaptation [ 36 ]). SotA reviews focus on one domain’s body of literature to construct a timeline of knowledge development, demarcating where we are now, demonstrating how this understanding came to be via different turning points, and offering new research directions. Certainly, SotA reviews offer a unique kind of knowledge synthesis.

Our six-stage process for conducting these reviews reflects the subjectivist relativism that underpins the methodology. It aligns with the requirements proposed by others [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ], what has been written about SotA reviews [ 4 , 5 ], and the current body of published SotA reviews. In contrast to existing guidance [ 4 , 5 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ], our description offers a detailed reporting of the ontology, epistemology, and methodology processes for conducting the SotA review.

This explicit methodology description is essential since many academic journals list SotA reviews as an accepted type of literature review. For instance, Educational Research Review [ 24 ], the American Academy of Pediatrics [ 25 ], and Thorax all lists SotA reviews as one of the types of knowledge syntheses they accept [ 27 ]. However, while SotA reviews are valued by academia, guidelines or specific methodology descriptions for researchers to follow when conducting this type of knowledge synthesis are conspicuously absent. If academics in general, and medical education more specifically, are to take advantage of the insights that SotA reviews can offer, we need to rigorously engage in this synthesis work; to do that, we need clear descriptions of the methodology underpinning this review. This article offers such a description. We hope that more medical educators will conduct SotA reviews to generate insights that will contribute to further advancing our field’s research and scholarship.

Cooper HM. Organizing knowledge syntheses: a taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowl Soc. 1988;1:104.

Google Scholar

Badger D, Nursten J, Williams P, Woodward M. Should all literature reviews be systematic? Eval Res Educ. 2000;14:220–30.

Article Google Scholar

Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2019;104:333–9.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91–108.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Info Libr J. 2019;36:202–22.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE, World Health Organization, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Jackson R, Feder G. Guidelines for clinical guidelines: a simple, pragmatic strategy for guideline development. Br Med J. 1998;317:427–8.

Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48:e12931.

Bach QV, Chen WH. Pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics of microalgae via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA): a state-of-the-art review. Bioresour Technol. 2017;246:88–100.

Garofalo C, Milanović V, Cardinali F, Aquilanti L, Clementi F, Osimani A. Current knowledge on the microbiota of edible insects intended for human consumption: a state-of-the-art review. Food Res Int. 2019;125:108527.

Carbone S, Dixon DL, Buckley LF, Abbate A. Glucose-lowering therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: state-of-the-art review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1629–47.

Hofkens PJ, Verrijcken A, Merveille K, et al. Common pitfalls and tips and tricks to get the most out of your transpulmonary thermodilution device: results of a survey and state-of-the-art review. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015;47:89–116.

Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. A history of assessment in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25:1045–56.

Arena A, Prete F, Rambaldi E, et al. Nanostructured zirconia-based ceramics and composites in dentistry: a state-of-the-art review. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:1393.

Bahraminasab M, Farahmand F. State of the art review on design and manufacture of hybrid biomedical materials: hip and knee prostheses. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2017;231:785–813.

Maggio LA, Costello JA, Norton C, Driessen EW, Artino AR Jr. Knowledge syntheses in medical education: a bibliometric analysis. Perspect Med Educ. 2021;10:79–87.

McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009. Med Educ. 2010;44:50–63.

Krishnan DG, Keloth AV, Ubedulla S. Pros and cons of simulation in medical education: a review. Education. 2017;3:84–7.

National Library of Medicine. MEDLINE: overview. 2021. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medline/medline_overview.html . Accessed 17 Dec 2021.

Bergman E, de Feijter J, Frambach J, et al. AM last page: a guide to research paradigms relevant to medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:545.

Maggio LA, Samuel A, Stellrecht E. Systematic reviews in medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:171–5.

Bandari J, Wessel CB, Jacobs BL. Comparative effectiveness in urology: a state of the art review utilizing a systematic approach. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:380–94.

Elsevier. A guide for writing scholarly articles or reviews for the educational research review. 2010. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/edurevReviewPaperWriting.pdf . Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics author guidelines. 2020. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/page/author-guidelines . Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology. JACC instructions for authors. 2020. https://www.jacc.org/pb-assets/documents/author-instructions-jacc-1598995793940.pdf . Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Thorax. Authors. 2020. https://thorax.bmj.com/pages/authors/ . Accessed 3 Mar 2020.

Berven S, Carl A. State of the art review. Spine Deform. 2019;7:381.

Ilardi CR, Chieffi S, Iachini T, Iavarone A. Neuropsychology of posteromedial parietal cortex and conversion factors from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: systematic search and state-of-the-art review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34:289–307.

Chan KS, Zary N. Applications and challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in medical education: integrative review. JMIR Med Educ. 2019;5:e13930.

World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice . Accessed July 1 2021.

Hammersley M. On ‘systematic’ reviews of research literatures: a ‘narrative’ response to Evans & Benefield. Br Educ Res J. 2001;27:543–54.

Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51:585–97.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Matsas B, Goralnick E, Bass M, Barnett E, Nagle B, Sullivan E. Leadership development in US undergraduate medical education: a scoping review of curricular content and competency frameworks. Acad Med. 2022;97:899–908.

Cristancho SM. On collective self-healing and traces: How can swarm intelligence help us think differently about team adaptation? Med Educ. 2021;55:441–7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Rhonda Allard for her help with the literature review and compiling all available articles. We also want to thank the PME editors who offered excellent development and refinement suggestions that greatly improved this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anesthesiology, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA

Erin S. Barry

School of Health Professions Education (SHE), Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Department of Medicine, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA

Jerusalem Merkebu & Lara Varpio

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Erin S. Barry .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

E.S. Barry, J. Merkebu and L. Varpio declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

The opinions and assertions contained in this article are solely those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

Supplementary Information

40037_2022_725_moesm1_esm.docx.

For information regarding the search strategy to develop the corpus and search strategy for confirming capture of any available State of the Art review methodology descriptions. Additionally, a list of the methodology articles found through the search strategy/corpus is included

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barry, E.S., Merkebu, J. & Varpio, L. State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis. Perspect Med Educ 11 , 281–288 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-022-00725-9

Download citation

Received : 03 December 2021

Revised : 25 July 2022

Accepted : 27 July 2022

Published : 05 September 2022

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-022-00725-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- State-of-the-art literature review

- Literature review

- Literature review methodology

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods and Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences

- > Literature Review

Book contents

- The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods and Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology

- Copyright page

- Contributors

- Part I From Idea to Reality: The Basics of Research

- 1 Promises and Pitfalls of Theory

- 2 Research Ethics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences

- 3 Getting Good Ideas and Making the Most of Them

- 4 Literature Review

- 5 Choosing a Research Design

- 6 Building the Study

- 7 Analyzing Data

- 8 Writing the Paper

- Part II The Building Blocks of a Study

- Part III Data Collection

- Part IV Statistical Approaches

- Part V Tips for a Successful Research Career

4 - Literature Review

from Part I - From Idea to Reality: The Basics of Research

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 May 2023

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources that establishes familiarity with and an understanding of current research in a particular field. It includes a critical analysis of the relationship among different works, seeking a synthesis and an explanation of gaps, while relating findings to the project at hand. It also serves as a foundational aspect of a well-grounded thesis or dissertation, reveals gaps in a specific field, and establishes credibility and need for those applying for a grant. The enormous amount of textual information necessitates the development of tools to help researchers effectively and efficiently process huge amounts of data and quickly search, classify, and assess their relevance. This chapter presents an assessable guide to writing a comprehensive review of literature. It begins with a discussion of the purpose of the literature review and then presents steps to conduct an organized, relevant review.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Literature Review

- By Rachel Adams Goertel

- Edited by Austin Lee Nichols , Central European University, Vienna , John Edlund , Rochester Institute of Technology, New York

- Book: The Cambridge Handbook of Research Methods and Statistics for the Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Online publication: 25 May 2023

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009010054.005

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.