Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

What is the difference between "introduction" and "motivation" sections

I am working on a paper about a web data extractor (an application, I developed based on a unique approach). In the introduction I had a short review on the history of such applications (from hard-code to graphical user interface) and said my application belong to this latest group. However, I didn't say much about the approach I adopted in the application. I left it to be discussed in the motivation section.

In motivation section I counted the features of existing approaches and described the features of the approach I followed.

Now I think maybe I should merge these two sections into one section, as I read the introduction I can't get what is the difference of my application with existing. Should such information be put in the introduction?

In general, what is the scope of 'Introduction' and 'Motivation' sections?

- publications

2 Answers 2

Introduction: what.

The introduction of a scientific publication is where you explain the background of your research. What are you building on? What does the reader need to know to properly understand your presented work? What is your hypothesis (if this sort of thing is relevant to your field)?

Motivation: WHY

The motivation section explains the importance behind your research. Why should the reader care? Why is your research the most groundbreaking piece of scientific knowledge since sliced bread (or CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing)?

Some people do combine the introduction and the motivation, it really depends on the research and the researcher. There is generally a fair amount of overlap between introducing related work, and then saying that your work goes above and beyond this previous research. Remember that these are just two of the big questions you need to answer with your paper. Others include:

Methods: HOW

Results: what happened, discussion: so.

They are whatever you want them to be. Neither of them are required by any journal that I know of. These kinds of sections are just conventional. You want to tell a story leading your readers from where you started to what you learned. That's basically it. The sections like Introduction, Motivation, Literature Review, Prior Work, Methodology, Approach, Results, Discussion, Future Work, and Conclusions are sign posts to help your readers know what you're about to tell them about. Readers can use them to skip around if they are skimming your article.

If you want to combine your Introduction and Motivation into one introductory section, that's up to you. Just tell a good, coherent story that leads your reader through your material.

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged publications writing ..

- Featured on Meta

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

- We've made changes to our Terms of Service & Privacy Policy - July 2024

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- Can figere come with a dative?

- Visualizing histogram of data on unit circle?

- Difference between 頁 and ページ

- Does gluing two points prevent simple connectedness?

- Op Amp Feedback Resistors

- Group automorphism fixing finite-index subgroup

- When testing for normally distributed data, should I consider all variables before running shapiro.test?

- How to justify a ban on exclusivist religions?

- how replicate this effect with geometry nodes

- Difficulty understanding grammar in sentence

- Calculate the sum of numbers in a rectangle

- Will this be the first time, that there are more People an ISS than seats in docked Spacecraft?

- Vector of integers such that almost all dot products are positive

- Copper bonding jumper around new whole-house water filter system

- How to ensure a BSD licensed open source project is not closed in the future?

- Postdoc supervisor has stopped helping

- How to extract code into library allowing changes without workflow overhead

- Print tree of uninstalled dependencies and their filesizes for apt packages

- Can pedestrians and cyclists board shuttle trains in the Channel Tunnel?

- Which game is "that 651"?

- How do logic gates handle if-else statements?

- If Miles doesn’t consider Peter’s actions as hacking, then what does he think Peter is doing to the computer?

- What's the Matter?

- What's the counterpart to "spheroid" for a circle? There's no "circoid"

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Setting Goals & Staying Motivated

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This vidcast talks about how to set goals and how to maintain motivation for long writing tasks. When setting goals for a writing project, it is important to think about goals for the entire project and also goals for specific writing times. These latter goals should be specific, measurable, and manageable within the time allotted for writing. The section on motivation shares ideas for boosting motivation over the course of a long writing project. The handouts on goal-setting and staying productive, as well as the scholarly writing inventory, complement the material in this vidcast and should be used in conjunction with it.

Note: Closed-captioning and a full transcript are available for this vidcast.

Handouts

Goal-Setting for your Personal Intensive Writing Experience (IWE) | [PDF]

This handout guides writers through the important process of goal-setting for the personal Intensive Writing Experience. Specifically, it talks about how to (1) formulate specific, measurable, and reasonable writing goals, (2) set an overall IWE goal, (3) break up the overall goal into smaller, daily goals, and (4) break up daily goals into smaller goals for individual writing sessions. Writers are prompted to clear their head of distracting thoughts before each writing session and, after each session, to debrief on their progress and recalibrate goals as needed.

Scholarly Writing Inventory (PDF)

This questionnaire helps writers identify and inventory their personal strengths and weaknesses as scholarly writers. Specifically, writers are prompted to answer questions pertaining to (1) the emotional/psychological aspects of writing, (2) writing routines, (3) research, (4) organization, (5) citation, (6) mechanics, (7) social support, and (8) access to help. By completing this questionnaire, scholarly writers will find themselves in a better position to build upon their strengths and address their weaknesses.

Stay ing Productive for Long Writing Tasks (PDF)

This resource offers some practical tips and tools to assist writers in staying productive for extended periods of time in the face of common challenges like procrastination. It discusses how the process of writing is more than putting words on a page and offers suggestions for addressing negative emotions towards writing, such as anxiety. The handout also lays out helpful methods for staying productive for long writing tasks: (1) time-based methods, (2) social-based methods, (3) output-based methods, (4) reward-based methods, and (5) mixed methods.

How To Write A Dissertation Introduction

A Simple Explainer With Examples + Free Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By Dr Eunice Rautenbach (D. Tech) | March 2020

If you’re reading this, you’re probably at the daunting early phases of writing up the introduction chapter of your dissertation or thesis. It can be intimidating, I know.

In this post, we’ll look at the 7 essential ingredients of a strong dissertation or thesis introduction chapter, as well as the essential things you need to keep in mind as you craft each section. We’ll also share some useful tips to help you optimize your approach.

Overview: Writing An Introduction Chapter

- The purpose and function of the intro chapter

- Craft an enticing and engaging opening section

- Provide a background and context to the study

- Clearly define the research problem

- State your research aims, objectives and questions

- Explain the significance of your study

- Identify the limitations of your research

- Outline the structure of your dissertation or thesis

A quick sidenote:

You’ll notice that I’ve used the words dissertation and thesis interchangeably. While these terms reflect different levels of research – for example, Masters vs PhD-level research – the introduction chapter generally contains the same 7 essential ingredients regardless of level. So, in this post, dissertation introduction equals thesis introduction.

Start with why.

To craft a high-quality dissertation or thesis introduction chapter, you need to understand exactly what this chapter needs to achieve. In other words, what’s its purpose ? As the name suggests, the introduction chapter needs to introduce the reader to your research so that they understand what you’re trying to figure out, or what problem you’re trying to solve. More specifically, you need to answer four important questions in your introduction chapter.

These questions are:

- What will you be researching? (in other words, your research topic)

- Why is that worthwhile? (in other words, your justification)

- What will the scope of your research be? (in other words, what will you cover and what won’t you cover)

- What will the limitations of your research be? (in other words, what will the potential shortcomings of your research be?)

Simply put, your dissertation’s introduction chapter needs to provide an overview of your planned research , as well as a clear rationale for it. In other words, this chapter has to explain the “what” and the “why” of your research – what’s it all about and why’s that important.

Simple enough, right?

Well, the trick is finding the appropriate depth of information. As the researcher, you’ll be extremely close to your topic and this makes it easy to get caught up in the minor details. While these intricate details might be interesting, you need to write your introduction chapter on more of a “need-to-know” type basis, or it will end up way too lengthy and dense. You need to balance painting a clear picture with keeping things concise. Don’t worry though – you’ll be able to explore all the intricate details in later chapters.

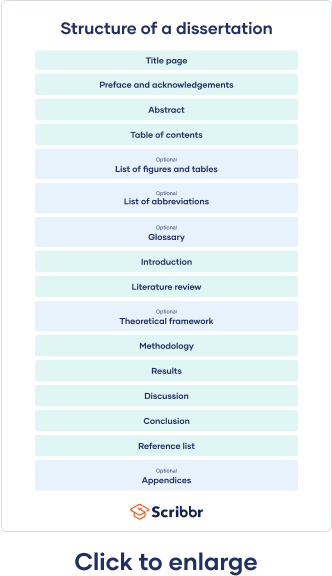

Now that you understand what you need to achieve from your introduction chapter, we can get into the details. While the exact requirements for this chapter can vary from university to university, there are seven core components that most universities will require. We call these the seven essential ingredients .

The 7 Essential Ingredients

- The opening section – where you’ll introduce the reader to your research in high-level terms

- The background to the study – where you’ll explain the context of your project

- The research problem – where you’ll explain the “gap” that exists in the current research

- The research aims , objectives and questions – where you’ll clearly state what your research will aim to achieve

- The significance (or justification) – where you’ll explain why your research is worth doing and the value it will provide to the world

- The limitations – where you’ll acknowledge the potential limitations of your project and approach

- The structure – where you’ll briefly outline the structure of your dissertation or thesis to help orient the reader

By incorporating these seven essential ingredients into your introduction chapter, you’ll comprehensively cover both the “ what ” and the “ why ” I mentioned earlier – in other words, you’ll achieve the purpose of the chapter.

Side note – you can also use these 7 ingredients in this order as the structure for your chapter to ensure a smooth, logical flow. This isn’t essential, but, generally speaking, it helps create an engaging narrative that’s easy for your reader to understand. If you’d like, you can also download our free introduction chapter template here.

Alright – let’s look at each of the ingredients now.

#1 – The Opening Section

The very first essential ingredient for your dissertation introduction is, well, an introduction or opening section. Just like every other chapter, your introduction chapter needs to start by providing a brief overview of what you’ll be covering in the chapter.

This section needs to engage the reader with clear, concise language that can be easily understood and digested. If the reader (your marker!) has to struggle through it, they’ll lose interest, which will make it harder for you to earn marks. Just because you’re writing an academic paper doesn’t mean you can ignore the basic principles of engaging writing used by marketers, bloggers, and journalists. At the end of the day, you’re all trying to sell an idea – yours is just a research idea.

So, what goes into this opening section?

Well, while there’s no set formula, it’s a good idea to include the following four foundational sentences in your opening section:

1 – A sentence or two introducing the overall field of your research.

For example:

“Organisational skills development involves identifying current or potential skills gaps within a business and developing programs to resolve these gaps. Management research, including X, Y and Z, has clearly established that organisational skills development is an essential contributor to business growth.”

2 – A sentence introducing your specific research problem.

“However, there are conflicting views and an overall lack of research regarding how best to manage skills development initiatives in highly dynamic environments where subject knowledge is rapidly and continuously evolving – for example, in the website development industry.”

3 – A sentence stating your research aims and objectives.

“This research aims to identify and evaluate skills development approaches and strategies for highly dynamic industries in which subject knowledge is continuously evolving.”.

4 – A sentence outlining the layout of the chapter.

“This chapter will provide an introduction to the study by first discussing the background and context, followed by the research problem, the research aims, objectives and questions, the significance and finally, the limitations.”

As I mentioned, this opening section of your introduction chapter shouldn’t be lengthy . Typically, these four sentences should fit neatly into one or two paragraphs, max. What you’re aiming for here is a clear, concise introduction to your research – not a detailed account.

PS – If some of this terminology sounds unfamiliar, don’t stress – I’ll explain each of the concepts later in this post.

#2 – Background to the study

Now that you’ve provided a high-level overview of your dissertation or thesis, it’s time to go a little deeper and lay a foundation for your research topic. This foundation is what the second ingredient is all about – the background to your study.

So, what is the background section all about?

Well, this section of your introduction chapter should provide a broad overview of the topic area that you’ll be researching, as well as the current contextual factors . This could include, for example, a brief history of the topic, recent developments in the area, key pieces of research in the area and so on. In other words, in this section, you need to provide the relevant background information to give the reader a decent foundational understanding of your research area.

Let’s look at an example to make this a little more concrete.

If we stick with the skills development topic I mentioned earlier, the background to the study section would start by providing an overview of the skills development area and outline the key existing research. Then, it would go on to discuss how the modern-day context has created a new challenge for traditional skills development strategies and approaches. Specifically, that in many industries, technical knowledge is constantly and rapidly evolving, and traditional education providers struggle to keep up with the pace of new technologies.

Importantly, you need to write this section with the assumption that the reader is not an expert in your topic area. So, if there are industry-specific jargon and complex terminology, you should briefly explain that here , so that the reader can understand the rest of your document.

Don’t make assumptions about the reader’s knowledge – in most cases, your markers will not be able to ask you questions if they don’t understand something. So, always err on the safe side and explain anything that’s not common knowledge.

#3 – The research problem

Now that you’ve given your reader an overview of your research area, it’s time to get specific about the research problem that you’ll address in your dissertation or thesis. While the background section would have alluded to a potential research problem (or even multiple research problems), the purpose of this section is to narrow the focus and highlight the specific research problem you’ll focus on.

But, what exactly is a research problem, you ask?

Well, a research problem can be any issue or question for which there isn’t already a well-established and agreed-upon answer in the existing research. In other words, a research problem exists when there’s a need to answer a question (or set of questions), but there’s a gap in the existing literature , or the existing research is conflicting and/or inconsistent.

So, to present your research problem, you need to make it clear what exactly is missing in the current literature and why this is a problem . It’s usually a good idea to structure this discussion into three sections – specifically:

- What’s already well-established in the literature (in other words, the current state of research)

- What’s missing in the literature (in other words, the literature gap)

- Why this is a problem (in other words, why it’s important to fill this gap)

Let’s look at an example of this structure using the skills development topic.

Organisational skills development is critically important for employee satisfaction and company performance (reference). Numerous studies have investigated strategies and approaches to manage skills development programs within organisations (reference).

(this paragraph explains what’s already well-established in the literature)

However, these studies have traditionally focused on relatively slow-paced industries where key skills and knowledge do not change particularly often. This body of theory presents a problem for industries that face a rapidly changing skills landscape – for example, the website development industry – where new platforms, languages and best practices emerge on an extremely frequent basis.

(this paragraph explains what’s missing from the literature)

As a result, the existing research is inadequate for industries in which essential knowledge and skills are constantly and rapidly evolving, as it assumes a slow pace of knowledge development. Industries in such environments, therefore, find themselves ill-equipped in terms of skills development strategies and approaches.

(this paragraph explains why the research gap is problematic)

As you can see in this example, in a few lines, we’ve explained (1) the current state of research, (2) the literature gap and (3) why that gap is problematic. By doing this, the research problem is made crystal clear, which lays the foundation for the next ingredient.

#4 – The research aims, objectives and questions

Now that you’ve clearly identified your research problem, it’s time to identify your research aims and objectives , as well as your research questions . In other words, it’s time to explain what you’re going to do about the research problem.

So, what do you need to do here?

Well, the starting point is to clearly state your research aim (or aims) . The research aim is the main goal or the overarching purpose of your dissertation or thesis. In other words, it’s a high-level statement of what you’re aiming to achieve.

Let’s look at an example, sticking with the skills development topic:

“Given the lack of research regarding organisational skills development in fast-moving industries, this study will aim to identify and evaluate the skills development approaches utilised by web development companies in the UK”.

As you can see in this example, the research aim is clearly outlined, as well as the specific context in which the research will be undertaken (in other words, web development companies in the UK).

Next up is the research objective (or objectives) . While the research aims cover the high-level “what”, the research objectives are a bit more practically oriented, looking at specific things you’ll be doing to achieve those research aims.

Let’s take a look at an example of some research objectives (ROs) to fit the research aim.

- RO1 – To identify common skills development strategies and approaches utilised by web development companies in the UK.

- RO2 – To evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies and approaches.

- RO3 – To compare and contrast these strategies and approaches in terms of their strengths and weaknesses.

As you can see from this example, these objectives describe the actions you’ll take and the specific things you’ll investigate in order to achieve your research aims. They break down the research aims into more specific, actionable objectives.

The final step is to state your research questions . Your research questions bring the aims and objectives another level “down to earth”. These are the specific questions that your dissertation or theses will seek to answer. They’re not fluffy, ambiguous or conceptual – they’re very specific and you’ll need to directly answer them in your conclusions chapter .

The research questions typically relate directly to the research objectives and sometimes can look a bit obvious, but they are still extremely important. Let’s take a look at an example of the research questions (RQs) that would flow from the research objectives I mentioned earlier.

- RQ1 – What skills development strategies and approaches are currently being used by web development companies in the UK?

- RQ2 – How effective are each of these strategies and approaches?

- RQ3 – What are the strengths and weaknesses of each of these strategies and approaches?

As you can see, the research questions mimic the research objectives , but they are presented in question format. These questions will act as the driving force throughout your dissertation or thesis – from the literature review to the methodology and onward – so they’re really important.

A final note about this section – it’s really important to be clear about the scope of your study (more technically, the delimitations ). In other words, what you WILL cover and what you WON’T cover. If your research aims, objectives and questions are too broad, you’ll risk losing focus or investigating a problem that is too big to solve within a single dissertation.

Simply put, you need to establish clear boundaries in your research. You can do this, for example, by limiting it to a specific industry, country or time period. That way, you’ll ringfence your research, which will allow you to investigate your topic deeply and thoroughly – which is what earns marks!

Need a helping hand?

#5 – Significance

Now that you’ve made it clear what you’ll be researching, it’s time to make a strong argument regarding your study’s importance and significance . In other words, now that you’ve covered the what, it’s time to cover the why – enter essential ingredient number 5 – significance.

Of course, by this stage, you’ve already briefly alluded to the importance of your study in your background and research problem sections, but you haven’t explicitly stated how your research findings will benefit the world . So, now’s your chance to clearly state how your study will benefit either industry , academia , or – ideally – both . In other words, you need to explain how your research will make a difference and what implications it will have .

Let’s take a look at an example.

“This study will contribute to the body of knowledge on skills development by incorporating skills development strategies and approaches for industries in which knowledge and skills are rapidly and constantly changing. This will help address the current shortage of research in this area and provide real-world value to organisations operating in such dynamic environments.”

As you can see in this example, the paragraph clearly explains how the research will help fill a gap in the literature and also provide practical real-world value to organisations.

This section doesn’t need to be particularly lengthy, but it does need to be convincing . You need to “sell” the value of your research here so that the reader understands why it’s worth committing an entire dissertation or thesis to it. This section needs to be the salesman of your research. So, spend some time thinking about the ways in which your research will make a unique contribution to the world and how the knowledge you create could benefit both academia and industry – and then “sell it” in this section.

#6 – The limitations

Now that you’ve “sold” your research to the reader and hopefully got them excited about what’s coming up in the rest of your dissertation, it’s time to briefly discuss the potential limitations of your research.

But you’re probably thinking, hold up – what limitations? My research is well thought out and carefully designed – why would there be limitations?

Well, no piece of research is perfect . This is especially true for a dissertation or thesis – which typically has a very low or zero budget, tight time constraints and limited researcher experience. Generally, your dissertation will be the first or second formal research project you’ve ever undertaken, so it’s unlikely to win any research awards…

Simply put, your research will invariably have limitations. Don’t stress yourself out though – this is completely acceptable (and expected). Even “professional” research has limitations – as I said, no piece of research is perfect. The key is to recognise the limitations upfront and be completely transparent about them, so that future researchers are aware of them and can improve the study’s design to minimise the limitations and strengthen the findings.

Generally, you’ll want to consider at least the following four common limitations. These are:

- Your scope – for example, perhaps your focus is very narrow and doesn’t consider how certain variables interact with each other.

- Your research methodology – for example, a qualitative methodology could be criticised for being overly subjective, or a quantitative methodology could be criticised for oversimplifying the situation (learn more about methodologies here ).

- Your resources – for example, a lack of time, money, equipment and your own research experience.

- The generalisability of your findings – for example, the findings from the study of a specific industry or country can’t necessarily be generalised to other industries or countries.

Don’t be shy here. There’s no use trying to hide the limitations or weaknesses of your research. In fact, the more critical you can be of your study, the better. The markers want to see that you are aware of the limitations as this demonstrates your understanding of research design – so be brutal.

#7 – The structural outline

Now that you’ve clearly communicated what your research is going to be about, why it’s important and what the limitations of your research will be, the final ingredient is the structural outline.The purpose of this section is simply to provide your reader with a roadmap of what to expect in terms of the structure of your dissertation or thesis.

In this section, you’ll need to provide a brief summary of each chapter’s purpose and contents (including the introduction chapter). A sentence or two explaining what you’ll do in each chapter is generally enough to orient the reader. You don’t want to get too detailed here – it’s purely an outline, not a summary of your research.

Let’s look at an example:

In Chapter One, the context of the study has been introduced. The research objectives and questions have been identified, and the value of such research argued. The limitations of the study have also been discussed.

In Chapter Two, the existing literature will be reviewed and a foundation of theory will be laid out to identify key skills development approaches and strategies within the context of fast-moving industries, especially technology-intensive industries.

In Chapter Three, the methodological choices will be explored. Specifically, the adoption of a qualitative, inductive research approach will be justified, and the broader research design will be discussed, including the limitations thereof.

So, as you can see from the example, this section is simply an outline of the chapter structure, allocating a short paragraph to each chapter. Done correctly, the outline will help your reader understand what to expect and reassure them that you’ll address the multiple facets of the study.

By the way – if you’re unsure of how to structure your dissertation or thesis, be sure to check out our video post which explains dissertation structure .

Keep calm and carry on.

Hopefully you feel a bit more prepared for this challenge of crafting your dissertation or thesis introduction chapter now. Take a deep breath and remember that Rome wasn’t built in a day – conquer one ingredient at a time and you’ll be firmly on the path to success.

Let’s quickly recap – the 7 ingredients are:

- The opening section – where you give a brief, high-level overview of what your research will be about.

- The study background – where you introduce the reader to key theory, concepts and terminology, as well as the context of your study.

- The research problem – where you explain what the problem with the current research is. In other words, the research gap.

- The research aims , objectives and questions – where you clearly state what your dissertation will investigate.

- The significance – where you explain what value your research will provide to the world.

- The limitations – where you explain what the potential shortcomings and limitations of your research may be.

- The structural outline – where you provide a high-level overview of the structure of your document

If you bake these ingredients into your dissertation introduction chapter, you’ll be well on your way to building an engaging introduction chapter that lays a rock-solid foundation for the rest of your document.

Remember, while we’ve covered the essential ingredients here, there may be some additional components that your university requires, so be sure to double-check your project brief!

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

44 Comments

Thanks very much for such an insight. I feel confident enough in undertaking my thesis on the survey;The future of facial recognition and learning non verbal interaction

Glad to hear that. Good luck with your thesis!

Thanks very much for such an insight. I feel confident now undertaking my thesis; The future of facial recognition and learning non verbal interaction.

Thanks so much for this article. I found myself struggling and wasting a lot of time in my thesis writing but after reading this article and watching some of your youtube videos, I now have a clear understanding of what is required for a thesis.

Thank you Derek, i find your each post so useful. Keep it up.

Thank you so much Derek ,for shedding the light and making it easier for me to handle the daunting task of academic writing .

Thanks do much Dereck for the comprehensive guide. It will assist me queit a lot in my thesis.

thanks a lot for helping

i LOVE the gifs, such a fun way to engage readers. thanks for the advice, much appreciated

Thanks a lot Derek! It will be really useful to the beginner in research!

You’re welcome

This is a well written, easily comprehensible, simple introduction to the basics of a Research Dissertation../the need to keep the reader in mind while writing the dissertation is an important point that is covered../ I appreciate the efforts of the author../

The instruction given are perfect and clear. I was supposed to take the course , unfortunately in Nepal the service is not avaialble.However, I am much more hopeful that you will provide require documents whatever you have produced so far.

Thank you very much

Thanks so much ❤️😘 I feel am ready to start writing my research methodology

This is genuinely the most effective advice I have ever been given regarding academia. Thank you so much!

This is one of the best write up I have seen in my road to PhD thesis. regards, this write up update my knowledge of research

I was looking for some good blogs related to Education hopefully your article will help. Thanks for sharing.

This is an awesome masterpiece. It is one of the most comprehensive guides to writing a Dissertation/Thesis I have seen and read.

You just saved me from going astray in writing a Dissertation for my undergraduate studies. I could not be more grateful for such a relevant guide like this. Thank you so much.

Thank you so much Derek, this has been extremely helpful!!

I do have one question though, in the limitations part do you refer to the scope as the focus of the research on a specific industry/country/chronological period? I assume that in order to talk about whether or not the research could be generalized, the above would need to be already presented and described in the introduction.

Thank you again!

Phew! You have genuinely rescued me. I was stuck how to go about my thesis. Now l have started. Thank you.

This is the very best guide in anything that has to do with thesis or dissertation writing. The numerous blends of examples and detailed insights make it worth a read and in fact, a treasure that is worthy to be bookmarked.

Thanks a lot for this masterpiece!

Powerful insight. I can now take a step

Thank you very much for these valuable introductions to thesis chapters. I saw all your videos about writing the introduction, discussion, and conclusion chapter. Then, I am wondering if we need to explain our research limitations in all three chapters, introduction, discussion, and conclusion? Isn’t it a bit redundant? If not, could you please explain how can we write in different ways? Thank you.

Excellent!!! Thank you…

Thanks for this informative content. I have a question. The research gap is mentioned in both the introduction and literature section. I would like to know how can I demonstrate the research gap in both sections without repeating the contents?

I’m incredibly grateful for this invaluable content. I’ve been dreading compiling my postgrad thesis but breaking each chapter down into sections has made it so much easier for me to engage with the material without feeling overwhelmed. After relying on your guidance, I’m really happy with how I’ve laid out my introduction.

Thank you for the informative content you provided

Hi Derrick and Team, thank you so much for the comprehensive guide on how to write a dissertation or a thesis introduction section. For some of us first-timers, it is a daunting task. However, the instruction with relevant examples makes it clear and easy to follow through. Much appreciated.

It was so helpful. God Bless you. Thanks very much

I thank you Grad coach for your priceless help. I have two questions I have learned from your video the limitations of the research presented in chapter one. but in another video also presented in chapter five. which chapter limitation should be included? If possible, I need your answer since I am doing my thesis. how can I explain If I am asked what is my motivation for this research?

You explain what moment in life caused you to have a peaked interest in the thesis topic. Personal experiences? Or something that had an impact on your life, or others. Something would have caused your drive of topic. Dig deep inside, the answer is within you!

Thank you guys for the great work you are doing. Honestly, you have made the research to be interesting and simplified. Even a novice will easily grasp the ideas you put forward, Thank you once again.

Excellent piece!

I feel like just settling for a good topic is usually the hardest part.

Thank you so much. My confidence has been completely destroyed during my first year of PhD and you have helped me pull myself together again

Happy to help 🙂

I am so glad I ran into your resources and did not waste time doing the wrong this. Research is now making so much sense now.

Gratitude to Derrick and the team I was looking for a solid article that would aid me in drafting the thesis’ introduction. I felt quite happy when I came across the piece you wrote because it was so well-written and insightful. I wish you success in the future.

thank you so much. God Bless you

Thank you so much Grad Coach for these helpful insights. Now I can get started, with a great deal of confidence.

It’s ‘alluded to’ not ‘eluded to’.

This is great!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Cookies & Privacy

- GETTING STARTED

- Introduction

- FUNDAMENTALS

- Acknowledgements

- Research questions & hypotheses

- Concepts, constructs & variables

- Research limitations

- Getting started

- Sampling Strategy

- Research Quality

- Research Ethics

- Data Analysis

The purpose statement

The purpose statement is made up of three major components: (1) the motivation driving your dissertation; (2) the significance of the research you plan to carry out; and (3) the research questions you are going to address. Starting the first major chapter of your dissertation (usually Chapter One: Introduction ), the purpose statement establishes the intent of your entire dissertation. Just like a great song that needs a great "hook", the purpose statement needs to draw the reader in and keep their attention. This article explains the purpose of each of these three components that make up the purpose statement.

The "motivation" driving your dissertation

The "significance" of the research you plan to carry out, the "research questions" you are going to address.

Your choice of dissertation topic should be driven by some kind of motivation . This motivation is usually a problem or issue that you feel needs to be addressed or solved. This part of the purpose statement aims to answer the question: Why should we care? In other words, why should we be interested in the research problem or issue that you want to address?

The types of motivation that may drive your dissertation will vary depending on the subject area you are studying, as well as the specific dissertation topic you are interested in. However, some of the broad types of motivation that undergraduate and master's level dissertation students try to address are based around (a) individuals , (b) organisations , and/or (c) society .

Individuals face many problems and issues ranging from those associated with welfare , to health , prosperity , freedoms , security , and so on. From a health perspective, you may be concerned with the rise in childhood obesity and the potential need for regulation to combat the advertising of fast food to children. In terms of welfare and freedoms , you may be interested in the introduction of new legislation that aims to protect discrimination in the workplace, and its implications for small businesses.

Organisations also have a wide range of problems and issues that need to be addressed, whether relating to people , finances , operations , competition , regulations , and so forth. From a people perspective, you may be interested in how organisations use flexible working options to alleviate employee stress and burnout. In terms of regulations , you may be concerned with the growth in Internet piracy and the ways that organisations are dealing with such a threat.

Society is another lens through which you can view problems and issues that need to be addressed. These may relate to a wide range of societal risks or other problems and issues such as factory farming, the potential legalisation of marijuana, the health-related effects of talking on cell phones, and so forth. You may be interested in understanding individuals? views towards the potential legalisation of marijuana; or how these views are influenced by individuals? knowledge of the side-effects of marijuana use.

When communicating the motivation driving your dissertation to the reader, it is important to explain why the problem or issue you are addressing is interesting : that is, why should the reader care? It is not sufficient to simply state what the problem or issue is.

Whilst the motivation component of your purpose statement explains why the reader should care about your dissertation, the significance component justifies the value of the dissertation. In other words: What contribution will the dissertation make to the literature? Why should anyone bother to perform this research? What is its value?

Even though dissertations are rarely "ground-breaking" at the undergraduate or master's level (and are not expected to be), they should still be significant in some way. This component of the Introduction chapter, which follows the motivation section, should explain what this significance is. In this respect, your research may be significant in one of a number of ways. It may:

Capitalise on a recent event

Reflect a break from the past

Target a new audience

Address a flaw in a previous study

Expand a particular field of study

Help an individual, group, organisation, or community

When writing your purpose statement, you will need to explain the relationship between the motivation driving your dissertation and the significance of the research you plan to carry out. These two factors - motivation and significance - must be intrinsically linked; that is, you cannot have one without the other. The key point is that you must be able to explain the relationship between the motivation driving your dissertation and one (or more) of the types of significance highlighted in the bullets above.

The motivation and significance components of your Introduction chapter should signal to the reader the general intent of your dissertation. However, the research questions that you set out indicate the specific intent of your dissertation. In other words, your research questions tell the reader exactly what you intend to try and address (or answer) throughout the dissertation process.

In addition, since there are different types of research question (i.e., quantitative , qualitative and mixed methods research questions), it should be obvious from the significance component of your purpose statement which of these types of research question you intend to tackle [see the section, Research Questions , to learn more].

Having established the research questions you are going to address, this completes the purpose statement. At this point, the reader should be clear about the overall intent of your dissertation. If you are in the process of writing up your dissertation, we would recommend including a Chapter Summaries section after the Research Questions section of your Introduction chapter. This helps to let the reader know what to expect next from your dissertation.

- Career Advice

8 Motivational Tips for Dissertation Writing

By Elisa Modolo

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istock.com/spicy truffel

Writing a dissertation is a grueling process that does not just require academic prowess, an excellent writing style and mastery of a very specific area of knowledge. It also demands discipline (in setting a writing schedule), perseverance (in keeping that schedule) and motivation (to get the writing done and the project completed).

The beginning of the academic year, with its array of looming deadlines, administrative procedures and mandatory adviser/graduate students/department meetings, can make it difficult to find motivation and hold on to it. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its utter disruption of normal operations, exacerbates this problem even further.

So, if you need additional motivation in these trying times, maybe a practice I followed when writing my own dissertation can help. I call it Motivational Post-it: a series of brief slogans to write on Post-it notes and put all over your desk or workstation, so you can see them every time you sit down to work. Here are some of mine.

Start with one (line/page). The idea of writing what may amount to hundreds of pages can feel disheartening, especially if you just started your project. So, if you find yourself staring at a white page while the white page stares back at you, don't think about the arduous work ahead. Focus on the present rather than the future. Start with one line or page. One is better than zero, and the lines, as well as pages, will accumulate over time if you keep it going regularly. Breaking down the work in more manageable chunks will get you writing and help you push through your writer's block.

Obsessing is not progressing. This is for all the perfectionists out there. I know it is not realistic to just stop obsessing on each line/quote/passage if you have done it for years and that is precisely what makes you great in an academic environment. Been there, done that! Thus, I propose what I call a “timed obsession”: leave a brief period -- such as three days -- out of the allotted time to obsess over the details of a specific chapter or phase of the project. Then, whether that chapter/project is now up to your standards or not, after your timed obsession, you let it go . You send it in as it is.

Finished is better than perfect. This is again along the lines of perfectionism, but it applies more broadly to the dissertation in its entirety rather than to the single chapters. Your dissertation is not (yet) an academic book. It has to pass the scrutiny of your dissertation committee -- not be published by a prestigious academic publishing house. Even if you wish to publish it in the future, that is not your goal right now.

Remember: the perfect dissertation does not exist, and a good dissertation is a finished or written dissertation. Prioritize writing all the chapters or completing all the experiments or sets of data rather than spending precious time refining small details in already written chapters.

Interruptions happen. When creating your writing schedule, try to plan with reasonable expectations on the amount and quality of your writing. That means you will need to accommodate the fact that some days you will exceed your writing goals, and some days you will not reach them, so your schedule will have to be adjusted accordingly.

Remember also to account for interruptions: it is normal and human to feel physically exhausted and/or emotionally drained in the middle of the daily emergency that is COVID-19. Recognize that such times will come and that you need a writing schedule flexible enough to allow you to get back on track without feeling overwhelmed.

Work backward. Write your introduction at the end. The intro to your entire dissertation? After you have written all the chapters, so you know precisely where you are going and which considerations to highlight. The intro to each single chapter? Again, after you have conducted your analysis, so you know which points you want your readers to concentrate on. In this way, you will create a more compelling text and avoid losing writing time at the very beginning that should be dedicated to the meat of your argument. (Note: This approach may not apply to those dissertations that acquire a linear approach.)

The most you can do is your best. Give it your best shot. Still feeling like your argument could have been more convincing or better framed? You did what you could, so you are at peace with your conscience. You cannot do more than your best.

Celebrate your accomplishments. Celebrate your achievements to feed your motivation. You sent your chapter in? Take one day to destress -- possibly with some pampering -- and celebrate this milestone. You reached your writing goals for today? Buy yourself a treat and/or your favorite latte and take a walk outside.

You may be tempted to capitalize on the adrenaline rush of completion or on being in the working/productive mind-set and try to tackle the next topic, but that is a recipe for burnout in the long run. Recognizing that you are progressing and getting closer to your main goal provides immediate reward and helps you envision your objective of completing a dissertation as feasible and attainable.

Why do you like it? If you got midway through your dissertation and are now feeling stuck, try focusing on the part of your project that you enjoy the most. That might be the close analysis of a particularly poignant passage or the application of a specific theory, method or approach to your data. If possible, see if you can start writing the chapter you are stuck on not from the beginning but from the portion that speaks to you the most.

Ask yourself: Which part of this study am I most looking forward to writing/dealing with? Then go there. The rest, the connective tissue between sections, will come. The goal is to get you going.

It can also be useful to just look at the beginning of your journey: Why did you choose this project? Focus on the reasons that got you interested in it in the first place. Remember the enthusiasm you felt when you started? The eagerness to jump right in? Tap in to that to motivate you to bring your project to the finish line.

Struggling to Create AI Policies? Ask Your Students

A professor at Florida International University tasked her students with devising an ethical guide to using AI in the

Share This Article

More from career advice.

The Warning Signs of Academic Layoffs

Ryan Anderson advises on how to tell if your institution is gearing up for them and how you can prepare and protect y

Legislation Isn’t All That Negatively Impacts DEI Practitioners

Many experience incivility, bullying, belittling and a disregard for their views and feelings on their own campuses,

4 Ways to Reduce Higher Ed’s Leadership Deficit

Without good people-management skills, we’ll perpetuate the workforce instability and turnover on our campuses, warns

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Writing a master’s or doctoral thesis is a tough job, and many students struggle with writer’s block and putting off work. The journey requires not just skill and knowledge but a sustained motivation for thesis writing. Here are eight essential strategies to help you find and maintain your motivation to write your thesis throughout the thesis writing process.

Know why you lack motivation

It’s important to understand whether you’re just avoiding writing (procrastination) or if you genuinely don’t feel interested in it (lack of motivation). Procrastination is when you delay writing even though you want to finish it, while a lack of motivation for thesis writing is when you have no interest in writing at all. Knowing the difference helps you find the right solution. Remember, not feeling motivated doesn’t mean you can’t write; it just might be less enjoyable.

Recognize external vs. internal motivation

In the early stages of your academic journey, things like job prospects or recognition may motivate you to write your thesis. These are external motivators. Over time, they might become less effective. That’s why it’s important to develop internal motivators, like a real passion for your topic, curiosity, or wanting to make a difference in your field. Shifting to these internal motivators can keep you energized about your thesis writing for a longer period.

Develop a writing plan

As you regularly spend time on your thesis, you’ll start to overcome any initial resistance. Planning and thinking about your work will make the next steps easier. You might find yourself working more than 20 minutes some days. As you progress, plan for longer thesis writing periods and set goals for completing each chapter.

Don’t overwhelm yourself

Getting stuck is normal in thesis or dissertation writing. Don’t view these challenges as impossible obstacles. If you’re frustrated or unsure, take a break for a few days. Then, consult your advisor or a mentor to discuss your challenges and find ways to move forward effectively.

Work on your thesis daily

Try to spend 15-20 minutes daily on tasks related to your thesis or dissertation. This includes reading, researching, outlining, and other preparatory activities. You can fit these tasks into short breaks throughout your day, like waiting for appointments, during commutes, or even while cooking.

Understand that thesis writing motivation changes

Realize that thesis writing motivation isn’t always the same; it changes over time. Your drive to write will vary with different stages of your research and life changes. Knowing that motivation can go up and down helps you adapt. When you feel less motivated, focus on small, doable parts of your work instead of big, intimidating goals.

Recharge your motivation regularly

Just like you need to rest and eat well to keep your body energized, your motivation for thesis writing needs to be refreshed too. Do things that boost your mental and creative energy. This could be talking with colleagues, attending workshops, or engaging in hobbies that relax you. Stay aware of your motivation levels and take action to rejuvenate them. This way, you can avoid burnout and keep a consistent pace in your thesis work.

Keep encouraging yourself

Repeating encouraging phrases like “I will finish my thesis by year’s end” or “I’ll complete a lot of work this week” can really help. Saying these affirmations regularly can focus your energy and keep you on track with your thesis writing motivation .

Remember, the amount you write can vary each day. Some days you might write a lot, and other days less. The key is to keep writing, even if it’s just rough ideas or jumbled thoughts. Don’t let the need for perfection stop you. Listening to podcasts where researchers talk about their writing experiences can also be inspiring and motivate you in your writing journey.

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

How to make your thesis supervision work for you.

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

- How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

- Presenting Research Data Effectively Through Tables and Figures

CACTUS Joins Hands with Taylor & Francis to Simplify Editorial Process with a Pioneering AI Solution

You may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), five things authors need to know when using..., 7 best referencing tools and citation management software..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal....

Managing Research Projects

- Staying Organized

Practical checklist of ideas to keep you motivated

Convert text files to audio.

- What happens after I'm done?

Goal Setting & Staying Motivated

Work through this online intensive writing workshop from Purdue Online Writing Lab

When Motivation Wanes

Listen to a PhD student talk about struggling with motivation and how to keep going

Keeping motivated when doing a dissertation or thesis

A professor and counselor from the Dublin Institute of Technology have a conversation about how to stay motivated when undertaking a dissertation or thesis.

Motivation is a key factor to success in completing your research project. Here's some advice on how to plan your schedule and stay motivated.

Make sure you stay grounded in your decision to embark on such a huge task. Is it a requirement for your degree? Then, what does a college degree mean to you and to your family? Think about how you’ll use this degree in your future career and how incredibly proud you’ll feel for accomplishing this goal! And, of course, think about your support system, family, and friends who believe in your college journey.

Now that you’ve identified why you are doing this project, it’s important to find people to help you keep your eye on the prize. Mentors can be teachers, spiritual leaders, or family friends who can give you guidance and help you stay on track.

To secure a support system:

- Identify one or more friends, family members, or mentors who can be your support

- Share your goals with them and ask them to help you keep these in mind when things get tough.

- Reach out to friends and peers who can motivate you by listening and sharing ideas.

When working on your research project, it will be critical to establish routines and schedules to keep yourself motivated and focused. Be sure to set interim achievable goals as well as long-term larger goals. Break down searching, reading, and writing work into manageable chunks and stick to a daily and weekly schedule.

You Can Handle Any Project in Small Chunks.

Use a calendar or to-do list to check off daily and weekly tasks that you accomplish

Keep a list of your long-term goals handy too (including career goals), so you can refer to them when you want to remind yourself of your ultimate goal: graduation!

Although your classmates are working on topics different from yours, find ways to connect about the challenges of long-term research and writing projects.

- Use email and video conferencing to stay connected if you cannot meet in person.

- Find out if your classmates are using group texts, Instagram, Twitter, etc. as another means to connect.

- Try setting up an online accountability group using a group text chat or Zoom to stay connected.

Staying positive and having a growth mindset is important to maintain motivation.

- If you are finding it difficult to stay positive about your project, talk to your instructor.

- You may also want to talk with other students to help you through challenging times.

- Remember to take the time to encourage others through chat, email, and social media.

- Reach out to your support system - mentors, teachers, family, friends, fellow classmates.

With all the hard work that you are doing, you need to take some time out to reward yourself. When you accomplish a goal, no matter how small, be sure to reward yourself with something that will make you happy! Whether it's a walk in your neighborhood, a FaceTime with family or friends, or watching your favorite Netflix series (try not to binge!), these rewards can help you stay motivated and on task.

Make a list of small rewards you can give yourself as you achieve your daily tasks. Make a list of bigger rewards you can give yourself as you finish bigger goals.

The information on this page is adapted from the Learning Online 101 Canvas module created by California State University, Channel Islands.

- Better yet, schedule it with a friend also working on a big project. You don't even need to talk!

- Schedule a library study room (or plan for another location) for this time. Knowing you have a room reserved and/or being in a different location might be the motivation you need.

- Work on tasks in 20 minute chunks to get you started.

- Convert some of the reading you need to do to audio , so you can keep making progress even if you can't sit down to read at the moment.

- Go back to the Planning Calculators and review what to do and when. But don't get overwhelmed! Put key dates on your calendar, and then make a list of only what you need to accomplish this week .

- Stay organized using a planner, such as this MS Excel Weekly Schedule Planner template .

- Use your commuting, walking, or cleaning time to listen to your course texts!

- Listen while you visually read along with a text to try to increase comprehension and memory.

- Use as a writing strategy: listen to your own writing as a way to notice areas to improve.

- Use a a motivation strategy; if you don't feel motivated to do anything, at least listening to readings will allow you to make some progress and may re-engage you in your work.

SPU has a tool called SensusAccess, which can convert text-based files to audio (plus other ways to change file types).

- Start at SPU’s SensusAccess Conversion Tool .

- (Step 1 of process) Upload a PDF document (or text or URL) you’d like converted to a streaming audio file. (If you have a print book, scan to PDF the section you need. If you are starting with a text file in another format, go straight to Step 6.)

- (Step 2) Select Accessibility conversion . This will send you a Word document, which will put header and footer info into correct places (it won't read you all those headers and footers) and which you can then edit otherwise as needed (don't need to listen to the 25 references at the end of the chapter? Delete them!).

- (Step 4) Email the file to yourself at your SPU email address, which takes only a few minutes to process.

- Re-start at SensusAccess Conversion Tool, and (Step 1) upload the Word document you’d been emailed.

- (Step 2) Select MP3 audio as the target format.

- (Step 3) Select language of document and audio speed (choose default to start, then consider another speed later if necessary).

- (Step 4) Email the streaming file to yourself. It may take longer to process, depending on the length of audio, but is usually ready with 5 min - 1 hour.

The streaming audio file will be a link in the email and is available for one week. If you need it longer, re-convert the Word file to mp3.

Happy listening!

audiobook by Clea Doltz is licensed CC BY 3.0 .

- << Previous: Staying Organized

- Next: Help!! >>

- Last Updated: Jun 19, 2024 4:48 PM

- URL: https://spu.libguides.com/ManagingProjects

- Current Students

- Study with Us

- Work with Us

How to write a research proposal for a Master's dissertation

Unsure how to start your research proposal as part of your dissertation read below our top tips from banking and finance student, nelly, on how to structure your proposal and make sure it's a strong, formative foundation to build your dissertation..

It's understandable if the proposal part of your dissertation feels like a waste of time. Why not just get started on the dissertation itself? Isn't 'proposal' a just fancy word for a plan?

It's important to see your Master's research proposal not only as a requirement but as a way of formalising your ideas and mapping out the direction and purpose of your dissertation. A strong, carefully prepared proposal is instrumental in writing a good dissertation.

How to structure a research proposal for a Master's dissertation

First things first: what do you need to include in a research proposal? The recommended structure of your proposal is:

- Motivation: introduce your research question and give an overview of the topic, explain the importance of your research

- Theory: draw on existing pieces of research that are relevant to your topic of choice, leading up to your question and identifying how your dissertation will explore new territory

- Data and methodology: how do you plan to answer the research question? Explain your data sources and methodology

- Expected results: finally, what will the outcome be? What do you think your data and methodology will find?

Top Tips for Writing a Dissertation Research Proposal

Choose a dissertation topic well in advance of starting to write it

Allow existing research to guide you

Make your research questions as specific as possible

When you choose a topic, it will naturally be very broad and general. For example, Market Efficiency . Under this umbrella term, there are so many questions you could explore and challenge. But, it's so important that you hone in on one very specific question, such as ' How do presidential elections affect market efficiency?' When it comes to your Master's, the more specific and clear-cut the better.

Collate your bibliography as you go

Everyone knows it's best practice to update your bibliography as you go, but that doesn't just apply to the main bibliography document you submit with your dissertation. Get in the habit of writing down the title, author and date of the relevant article next to every note you make - you'll be grateful you did it later down the line!

Colour code your notes based on which part of the proposal they apply to

Use highlighters and sticky notes to keep track of why you thought a certain research piece was useful, and what you intended to use it for. For example, if you've underlined lots of sections of a research article when it comes to pulling your research proposal together it will take you longer to remember what piece of research applies to where.

Instead, you may want to highlight anything that could inform your methodology in blue, any quotations that will form your theory in yellow etc. This will save you time and stress later down the line.

Write your Motivation after your Theory

Your Motivation section will be that much more coherent and specific if you write it after you've done all your research. All the reading you have done for your Theory will better cement the importance of your research, as well as provide plenty of context for you to write in detail your motivation. Think about the difference between ' I'm doing this because I'm interested in it ' vs. ' I'm doing this because I'm passionate, and I've noticed a clear gap in this area of study which is detailed below in example A, B and C .'

Make sure your Data and Methodology section is to the point and succinct

Link your Expectations to existing research

Your expectations should be based on research and data, not conjecture and assumptions. It doesn't matter if the end results match up to what you expected, as long as both of these sections are informed by research and data.

Published By Nelly on 01/09/2020 | Last Updated 23/01/2024

Related Articles

Why is English important for international students?

If you want to study at a UK university, knowledge of English is essential. Your degree will be taught in English and it will be the common language you share with friends. Being confident in English...

How to revise: 5 top revision techniques

Wondering how to revise for exams? It’s easy to get stuck in a loop of highlighting, copying out, reading and re-reading the same notes. But does it really work? Not all revision techniques are...

How can international students open a bank account in the UK?

Opening a student bank account in the UK can be a great way to manage your spending and take advantage of financial offers for university students. Read on to find out how to open a bank account as...

You May Also Like

- How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis

- Doing a PhD

What is a Thesis or Dissertation Abstract?

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines an abstract in academic writing as being “ a few sentences that give the main ideas in an article or a scientific paper ” and the Collins English Dictionary says “ an abstract of an article, document, or speech is a short piece of writing that gives the main points of it ”.

Whether you’re writing up your Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis, the abstract will be a key element of this document that you’ll want to make sure you give proper attention to.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

The aim of a thesis abstract is to give the reader a broad overview of what your research project was about and what you found that was novel, before he or she decides to read the entire thesis. The reality here though is that very few people will read the entire thesis, and not because they’re necessarily disinterested but because practically it’s too large a document for most people to have the time to read. The exception to this is your PhD examiner, however know that even they may not read the entire length of the document.

Some people may still skip to and read specific sections throughout your thesis such as the methodology, but the fact is that the abstract will be all that most read and will therefore be the section they base their opinions about your research on. In short, make sure you write a good, well-structured abstract.

How Long Should an Abstract Be?

If you’re a PhD student, having written your 100,000-word thesis, the abstract will be the 300 word summary included at the start of the thesis that succinctly explains the motivation for your study (i.e. why this research was needed), the main work you did (i.e. the focus of each chapter), what you found (the results) and concluding with how your research study contributed to new knowledge within your field.

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States of America, once famously said:

The point here is that it’s easier to talk open-endedly about a subject that you know a lot about than it is to condense the key points into a 10-minute speech; the same applies for an abstract. Three hundred words is not a lot of words which makes it even more difficult to condense three (or more) years of research into a coherent, interesting story.

What Makes a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

Whilst the abstract is one of the first sections in your PhD thesis, practically it’s probably the last aspect that you’ll ending up writing before sending the document to print. The reason being that you can’t write a summary about what you did, what you found and what it means until you’ve done the work.

A good abstract is one that can clearly explain to the reader in 300 words:

- What your research field actually is,

- What the gap in knowledge was in your field,

- The overarching aim and objectives of your PhD in response to these gaps,

- What methods you employed to achieve these,

- You key results and findings,

- How your work has added to further knowledge in your field of study.

Another way to think of this structure is:

- Introduction,

- Aims and objectives,

- Discussion,

- Conclusion.

Following this ‘formulaic’ approach to writing the abstract should hopefully make it a little easier to write but you can already see here that there’s a lot of information to convey in a very limited number of words.

How Do You Write a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

The biggest challenge you’ll have is getting all the 6 points mentioned above across in your abstract within the limit of 300 words . Your particular university may give some leeway in going a few words over this but it’s good practice to keep within this; the art of succinctly getting your information across is an important skill for a researcher to have and one that you’ll be called on to use regularly as you write papers for peer review.

Keep It Concise

Every word in the abstract is important so make sure you focus on only the key elements of your research and the main outcomes and significance of your project that you want the reader to know about. You may have come across incidental findings during your research which could be interesting to discuss but this should not happen in the abstract as you simply don’t have enough words. Furthermore, make sure everything you talk about in your thesis is actually described in the main thesis.

Make a Unique Point Each Sentence

Keep the sentences short and to the point. Each sentence should give the reader new, useful information about your research so there’s no need to write out your project title again. Give yourself one or two sentences to introduce your subject area and set the context for your project. Then another sentence or two to explain the gap in the knowledge; there’s no need or expectation for you to include references in the abstract.

Explain Your Research

Some people prefer to write their overarching aim whilst others set out their research questions as they correspond to the structure of their thesis chapters; the approach you use is up to you, as long as the reader can understand what your dissertation or thesis had set out to achieve. Knowing this will help the reader better understand if your results help to answer the research questions or if further work is needed.

Keep It Factual

Keep the content of the abstract factual; that is to say that you should avoid bringing too much or any opinion into it, which inevitably can make the writing seem vague in the points you’re trying to get across and even lacking in structure.

Write, Edit and Then Rewrite

Spend suitable time editing your text, and if necessary, completely re-writing it. Show the abstract to others and ask them to explain what they understand about your research – are they able to explain back to you each of the 6 structure points, including why your project was needed, the research questions and results, and the impact it had on your research field? It’s important that you’re able to convey what new knowledge you contributed to your field but be mindful when writing your abstract that you don’t inadvertently overstate the conclusions, impact and significance of your work.

Thesis and Dissertation Abstract Examples