- Make North America your preferred site edition

This year’s State of the Nation’s Housing 2023 report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies paints a stark picture of record unaffordability, near-record housing shortages and major barriers to first-time homeownership . Habitat for Humanity International co-sponsored the report through our Cost of Home campaign to help bring greater attention to these and other urgent housing challenges impacting the U.S. Below are four major takeaways from the report for Habitat’s work and the communities we serve:

1. Homeownership costs skyrocketed in 2022, pricing out 2.4 million renters.

According to Harvard’s JCHS, the estimated housing payments — including mortgage, insurance and property tax — needed to purchase a median-priced home in the U.S. reached $3,000 per month in March 2023, pricing out 2.4 million more renters from homebuying than last year. This included a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic homebuyers. The estimated annual income needed to afford median homeownership costs rose 20% to $117,000 — well above the national median income for renters.

Median home prices actually dropped slightly between early 2022 and early 2023, but this was more than outweighed by rising interest rates, which increased by more than half. As overall homeownership costs rose, first-time homebuying took a sizable hit. The number of first-time homebuyers starting a mortgage in 2022 declined 22% from the previous year, including a drop of 40% between the fourth quarters of 2022 and 2021.

2. Housing cost burdens reached their highest levels in years.

Housing cost burdens are defined as paying more than 30% of income on housing. During the pandemic, the number of existing homeowners experiencing cost burdens rose sharply. In 2021, 19 million homeowners (22.7%) were cost burdened — the highest level since 2013 . Of these, 8.7 million (10.4% of all homeowners) had housing costs that exceeded half their income. Cost burdens were especially prevalent for homeowners earning less than $30,000 per year, and higher than average for Black, Hispanic and Asian homeowners, as well as those over age 65.

For renters, the affordability picture was even worse. The number of cost-burdened renters reached an all-time high: 21.6 million households (49%) . Of this total, 11.6 million spent more than half of their income on housing (26.4% of all renters). High rates of cost burdens were most common for very low-income renters and households of color. They were also prevalent in not just high-rent markets such as Miami (61% of renters) and San Diego (57%), but also less costly metros like New Orleans (55%), Baton Rouge (55%) and Memphis (52%).

In total, 31.8% of all households (40.6 million homeowners and renters) were cost-burdened in 2021 . Of these, 20.3 million — nearly 1 in 6, or 15.9% of U.S. households — paid over half of their income on housing. For low-income households, such high cost burdens leave little left over for other necessities like food and healthcare.

3. The supply of homes for sale remains at near-record lows.

Record-low home sales aggravate home prices and increase barriers to homeownership, particularly for modest-income households and for homebuyers of color.

By the end of 2022, the supply of single-family homes for sale had inched above historic lows from the pandemic but was still 30% lower than at the end of 2019 (the previous record low). Also, the rate of single-family construction slowed dramatically in the second half of 2022, as rising mortgage interest rates diminished homebuyer purchasing power.

Shortages are greatest for lower-priced homes. Adding to this challenge, modest-sized home construction continues to decline. JCHS reports that less than a quarter of new homes were under 1,800 square feet in 2021, compared with 37% in 1999.

Rising land prices, high materials costs and regulatory barriers like zoning restrictions are among the chief challenges making it harder for nonprofit and for-profit home builders to build modest-sized, affordable homes.

4. States and localities are helping show the way forward.

Various states and localities reformed local zoning and other housing regulations this past year to make it easier to build affordable homes and bring down housing costs, with local and state Habitat organizations playing key advocacy roles.

For example:

- Washington and Montana became the latest states to make duplexes or other types of small-scale attached housing legal in most neighborhoods.

- Colorado created new funding incentives for localities to make their zoning codes more accommodating of affordable housing.

- Various localities took steps such as allowing smaller-lot developments, reducing building permits fees, and streamlining review processes to lower other barriers.

More localities and states should follow suit. To help, HUD’s new $85 million PRO Housing program will soon offer competitive grants to help states and localities address their own barriers to affordable housing. States and localities should take advantage of this opportunity.

Increased public investment will also be needed to make housing and homeownership affordable to more households with low incomes. To help, many Habitat affiliates advocated for new resources for entry-level homes and deeply affordable housing. This included legislative successes in Indiana, South Dakota and Wyoming, which dedicated funding to defray high infrastructure costs impeding starter homes. Advocacy successes in dozens of other states and localities raised new funding for building and sustaining affordable homes. It is critical to continue this momentum in the coming year.

More too is needed to continue progress in closing racial homeownership gaps. Even before interest rates spiked, homebuyers of color faced distinct barriers to homeownership stemming from decades of discriminatory policies resulting in less access to inter-generational wealth, among other disadvantages. In response, some states and localities recently created promising supplemental initiatives providing down payment assistance to first-generation homebuyers, descendants of residents displaced by highway construction or descendants of families excluded from homebuying opportunities by now-illegal, restrictive covenants. Also promising is Congress’s reintroduction of the bipartisan proposal for a Neighborhood Homes tax credit, which would help expand affordable homeownership supply in disinvested communities.

Lastly, the surge in existing homeowners facing high cost-burdens means now will be an important time to broaden repair assistance, property tax relief, and access to energy-efficient technologies for lower-income homeowners . Pennsylvania’s new Whole-Home Repairs Program, championed by Habitat Philadelphia and other local affiliates, is worth imitating in other states.

Habitats’ advocacy successes in Michigan and Baltimore promoting fairer property tax assessments for Habitat homes and easier access to existing property tax relief are also worth emulating. Lastly, the newly created Inflation Reduction Act will soon offer substantial energy-efficiency rebates and solar tax credits for lower-income homeowners to help lower utility expenses, reduce the costs of new construction, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Housing providers and policymakers should help distribute and leverage these resources to make sure they reach those most in need.

2023 State of the Nation’s Housing report

Read the full report, released by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies and proudly sponsored by Habitat for Humanity through the Cost of Home campaign.

Achieving policy solutions in the four areas laid out by our platform will enable families to have greater access to homes they can afford — and to all the opportunities that follow.

Take action to support the campaign today, and, together, we can help make the #CostOfHome something we all can afford.

- Enroll & Pay

- Current KU CMS Sites (Drupal 7)

Study finds US does not have housing shortage, but shortage of affordable housing

Mon, 06/17/2024

Mike Krings

LAWRENCE — The United States is experiencing a housing shortage. At least, that is the case according to common belief — and is even the basis for national policy, as the Biden administration has stated plans to address the housing supply shortfall.

But new research from the University of Kansas finds that most of the nation’s markets have ample housing in total, but nearly all lack enough units affordable to very low-income households.

Kirk McClure, professor of public affairs & administration emeritus at KU, and Alex Schwartz of The New School co-wrote a study published in the journal Housing Policy Debate . They examined U.S. Census Bureau data from 2000 to 2020 to compare the number of households formed to the number of housing units added to determine if there were more households needing homes than units available.

The researchers found only four of the nation’s 381 metropolitan areas experienced a housing shortage in the study time frame, as did only 19 of the country’s 526 "micropolitan" areas — those with 10,000-50,000 residents.

The findings suggest that addressing housing prices and low incomes are more urgently needed to address housing affordability issues than simply building more homes, the authors wrote.

“There is a commonly held belief that the United States has a shortage of housing. This can be found in the popular and academic literature and from the housing industry,” McClure said. “But the data shows that the majority of American markets have adequate supplies of housing available. Unfortunately, not enough of it is affordable, especially for low-income and very low-income families and individuals.”

McClure and Schwartz also examined households in two categories: Very low income, defined as between 30% and 60% of area median family income, and extremely low income, with incomes below 30% of area median family income.

The numbers showed that from 2010 to 2020, household formation did exceed the number of homes available. However, there was a large surplus of housing produced in the previous decade. In fact, from 2000 to 2020, housing production exceeded the growth of households by 3.3 million units. The surplus from 2000 to 2010 more than offset the shortages from 2010 to 2020.

The numbers also showed that nearly all metropolitan areas have sufficient units for owner occupancy. But nearly all have shortages of rental units affordable to the very low-income renter households.

While the authors looked at housing markets across the nation, they also examined vacancy rates, or the difference between total and occupied units, to determine how many homes were available. National total vacancy rates were 9% in 2000 and 11.4% by 2010, which marked the end of the housing bubble and the Great Recession. By the end of 2020, the rate was 9.7%, with nearly 14 million vacant units.

“When looking at the number of housing units available, it becomes clear there is no overall shortage of housing units available. Of course, there are many factors that determine if a vacant is truly available; namely, if it is physically habitable and how much it costs to purchase or rent the unit,” McClure said. “There are also considerations over a family’s needs such as an adequate number of bedrooms or accessibility for individuals with disabilities, but the number of homes needed has not outpaced the number of homes available.”

Not all housing markets are alike, and while there could be shortages in some, others could contain a surplus of available housing units. The study considered markets in all core-based statistical areas as defined by the Census Bureau. Metropolitan areas saw a nationwide surplus of 2.7 million more units than households in the 20-year study period, while micropolitan areas had a more modest surplus of about 300,000 units.

Numbers of available housing units and people only tell part of the story. An individual family needs to be able to afford housing, whether they buy or rent. Shortages of any scale appear in the data only when considering renters, the authors wrote. McClure and Schwartz compared the number of available units in four submarkets of each core-based statistical area to the estimated number of units affordable to renters with incomes from 30% to 60% of the area median family income. Those rates are roughly equivalent to the federal poverty level and upper level of eligibility for various rental assistance programs. Only two metropolitan areas had shortages for very-low-income renters, and only two had surpluses available for extremely-low-income renters.

Helping people afford the housing stock that is available would be more cost effective than expanding new home construction in the hope that additional supply would bring prices down, the authors wrote. Several federal programs have proven successful in helping renters and moderate-income buyers afford housing that would otherwise be out of reach.

“Our nation’s affordability problems result more from low incomes confronting high housing prices rather than from housing shortages,” McClure said. “This condition suggests that we cannot build our way to housing affordability. We need to address price levels and income levels to help low-income households afford the housing that already exists, rather than increasing the supply in the hope that prices will subside.”

Media Contacts

KU News Service

785-864-8860

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Alleviating Supply Constraints in the Housing Market

By Jared Bernstein, Jeffery Zhang, Ryan Cummings, and Matthew Maury

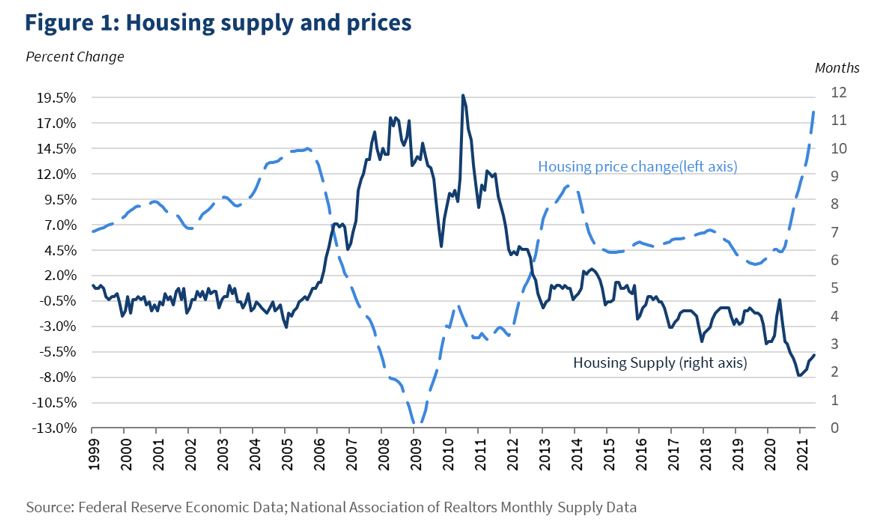

The COVID-19 pandemic shifted families’ preferences for location and type of housing, exacerbating existing supply chain constraints that—for several reasons—have persisted for many years. These pandemic-related changes interacted with the existing housing inventory shortage, resulting in sharp price increases for both owned homes and rental units. Indeed, national home prices, as measured by the Case-Shiller Index , increased by 7 to 19 percent (year-over-year) every month from September 2020 to June 2021. Home prices outpaced income growth in 2020, with the national price-to-income ratio rising to 4.4 —the highest observed level since 2006.

While the pandemic may have transformed preferences and caused supply chain disruptions, it did not create the underlying supply constraints in the housing market, which have decreased the stock of rental homes and homes for-sale. The pandemic exposed these constraints that have been around for decades and have impacted households across the income distribution. In the blog, we describe this perennial problem and outline the Administration’s wide-ranging proposals, including those in the Build Back Better agenda, to address the supply shortage and reduce price pressures in the housing market.

Through both legislative and non-legislative measures, these policies have the potential to create or rehabilitate over 2 million housing units, including at least 1 million rental units, based on HUD estimates from past program performance.

Supply Shortages in the Housing Market

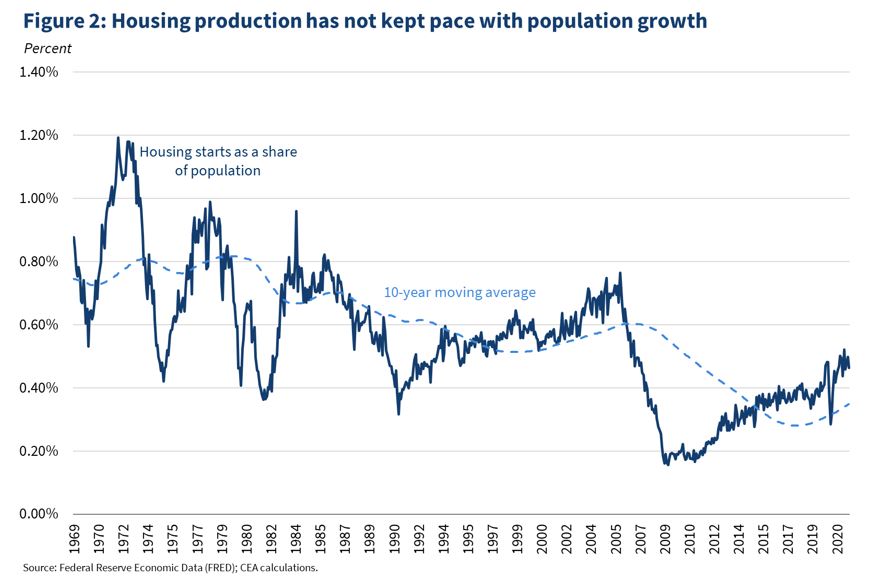

For the past 40 years, housing supply has not kept pace with population growth. A simple way to observe this fact is by looking at housing starts ( i.e. , new residential construction) as a share of the U.S. population. The figure above shows that housing starts as a share of the population has been on an overall decreasing trend since the 1970s. This decrease became particularly pronounced after the peak of the 2000s housing bubble. Housing starts as a share of the population decreased by roughly 39 percent in the 15-year period from January 2006 to June 2021. Researchers at Freddie Mac have estimated that the current shortage of homes is close to 3.8 million, up substantially from an estimated 2.5 million in 2018.

The above analysis looks at the housing market in aggregate, but there a large and portentous differences between segments of the market. One of the most important is that the number of new homes constructed below 1,400 square feet—typically considered “entry-level” homes for first-time homebuyers—has decreased sharply since the Great Recession and is more than 80 percent lower than the amount built in the 1970s. Similarly, entry-level homes are becoming a smaller fraction of the new homes that are being completed, representing less than 10 percent of all newly constructed homes, compared to roughly 35 percent in the 1970s. These dynamics mean that the critically important “bottom rung” of the home-ownership ladder is far too out-of-reach for young families trying to start building housing wealth.

The dearth of housing supply in the United States is caused by a range of factors and varies between markets. Many urban and suburban markets suffer from a shortage of available land . Part of the shortage of available land reflects public policy decisions of municipalities about how to use land. For example, while the greater Los Angeles area, which is experiencing a housing crisis that disproportionately affects people of color , currently has 84 golf courses (including eight municipal courses in Los Angeles proper) occupying an estimated 10,000 acres of land, a single 200-acre course could potentially provide housing for 50,000 people. Additionally, labor shortage s and the cost of building materials have increased in recent years.

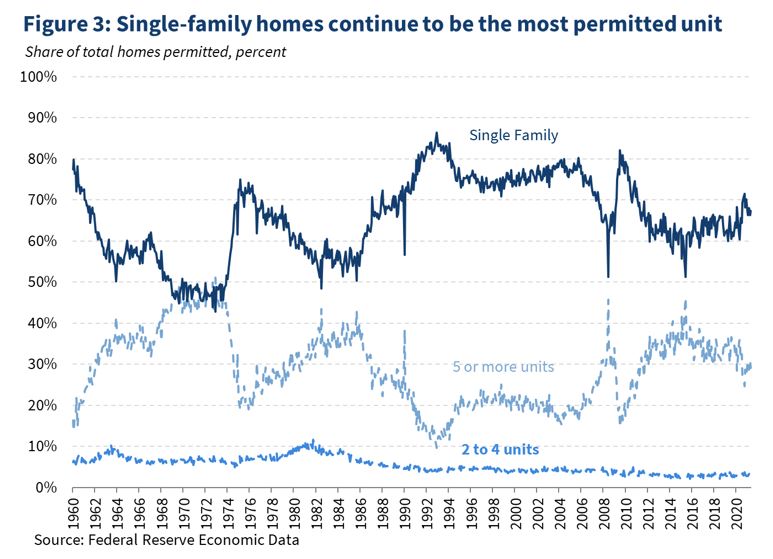

Another key factor driving limited housing supply is local zoning restrictions . For example, rigid single-family zoning, a practice linked with racial segregation , has prevented the construction of multi-family units, which would allow for higher density and an increased supply of housing. One can observe this limitation through the types of housing that have been permitted. As the figure below illustrates, single-family homes account for the majority of homes that receive permits to be built. Roughly 64 percent of all housing that has been authorized since the 2008 global financial crisis has been single-family homes. Units that have two to four residences and allow for multiple families to live on a single lot—as opposed to a large apartment which requires multiple lots to construct—have only accounted for roughly 3 percent of all permits since the financial crisis. Apartments and buildings with more than five units have accounted for approximately the remaining third.

Recently, there have been welcome developments in California and Oregon , at the State level, and Berkeley , Cambridge , Minneapolis , Oakland , and Sacramento , at the municipal level, to change the zoning regulations of these jurisdictions to allow more housing units on various land parcels. These moves offer much-needed potential to increase the housing supply, and are consistent with the Administration’s stance on the need for zoning reform.

In addition to the supply shortage in the homeownership market described above, the United States has an inadequate supply of housing for renters. Across the country, more than 10 million renters (one in four) pay more than half of their income on rent, and nearly half (47 percent) spend over the recommended 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities. From 2012 to 2017, the number of units that are rented for under $600 per month fell by 3.1 million, and the number of units rented for $600 to $999 fell by 450,000. These trends are no doubt partially driven by supply constraints. [1] Rental unit vacancy rates from 2019 to 2021 have been, on average, at their lowest levels in over 35 years. The problem of supply constraints appears to only be worsening. In July 2021, rental prices had increased by 8.3 percent year-over-year, the largest increase for which realty website RealPage has data. In addition, 65 of the country’s largest 150 metros are seeing price increases of over 10 percent year-over-year.

Public housing is also experiencing a supply shortage. Nearly two million people across the country live in public housing, including families with children, older Americans, and people with disabilities. Overall, over 5 million low-income households either live in public housing, privately-owned but publicly assisted housing, or receive rental assistance to find homes in the private market. However, since the 1990s, underfunding and deterioration of the units have decreased the nation’s public housing stock by over 200,000. Given that millions of renters pay half or more of their income on rent, this decline in public housing stock is the opposite of what should have occurred.

These supply constraints in the housing market have an impact on long-term economic growth and inequality. For instance, these constraints increase the cost of housing, which in turn limit labor mobility. Workers cannot afford to move to higher productivity regions that have high housing prices, leading them to remain in lower productivity places. One study finds that this misallocation of labor has led to a significant decrease in the U.S. economic growth rate since the 1960s. Another study estimates that this misallocation could cost up to 2 percent of GDP , which translates to more than $400 billion in lost economic output each year.

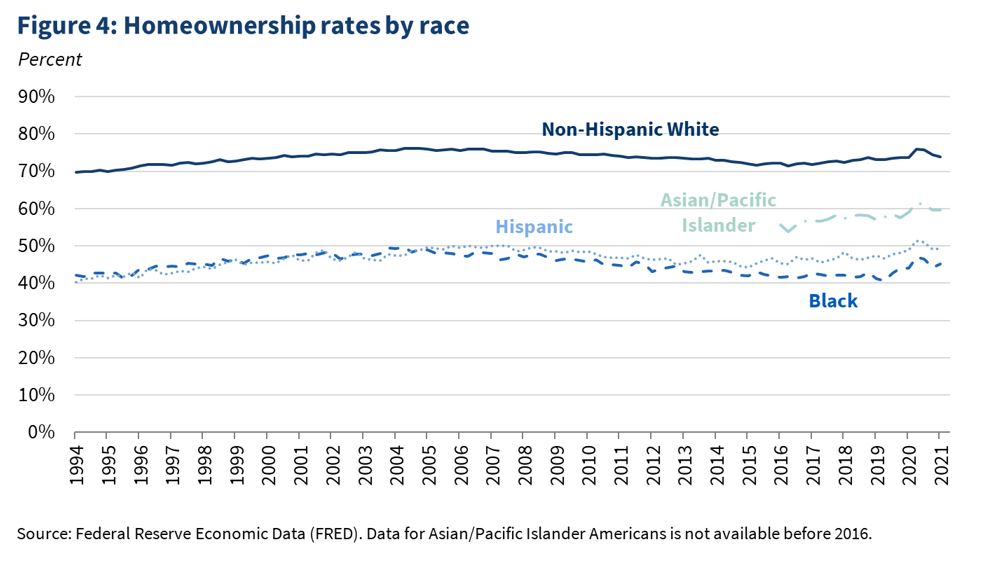

In addition, housing is a key driver of the racial wealth gap, potentially explaining more than 30 percent of the Black-white wealth gap. As the figure below highlights, the differences in homeownership among races has been large and persistent. Since 1994, the percentage of Black and Hispanic Americans who own a home has been roughly 25 to 30 percentage points lower than that of white Americans. For Asian and Pacific Islander Americans, this difference has been roughly 15 percentage points since 2016, when the data first become available. Researchers have found that alleviating supply constraints, which reinforce differences in homeownership rates, would have a significant impact on the racial wealth gap; if Black families were as likely as white families to own a home, median Black wealth would be $32,000 higher. For Hispanic families, equalizing the likelihood of owning a home would increase median Hispanic wealth by $29,000.

Proposals to Alleviate Supply Constraints

Because of their importance to racial equity, economic growth, and living standards, the Biden-Harris Administration has a robust agenda—tapping both legislative and administrative interventions—to address these supply constraints in the housing market.

Administrative Steps

Through coordination with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (“the Enterprises”), FHFA, HUD, Treasury, and State and local governments, the Administration plans to make use of available administrative opportunities to increase the supply of both single-family and multifamily housing. Estimates from HUD, FHFA, and Treasury show that these agencies will create, preserve, and deliver nearly 100,000 affordable housing units over the next three years.

As part of this plan, the Administration will take several concrete steps to ensure that single-family homes held by the Federal government eventually go to owner occupants, or to community-oriented non-profits committed to rehabilitating homes and selling them to owner occupants.

- HUD and the Enterprises plan to increase to 30 days, from 10–20 days, the period in which only non-profits and owner occupants—as opposed to financial market investors—can make offers on the more than 12,000 homes in their Real Estate Owned (“REO”) inventory. These are homes in their portfolio that have failed to sell in a foreclosure auction.

- Further, HUD and the Enterprises will continue to expand outreach to community-oriented non-profits and local governments regarding the sale of federally held homes. Because the Federal housing finance agencies guarantee mortgage repayments, the agencies often have a number of foreclosed homes in their portfolio. Under this new approach, they will cut through red-tape to ensure these properties quickly get on the market, with special access to those most in-need of such assistance.

The Administration also plans to increase financing for manufactured homes and 2–4 unit properties.

- FHFA will authorize Freddie Mac to purchase mortgages for single-wide manufactured homes, thereby extending its 2020 authorization to Fannie Mae. The Enterprises also will continue outreach on financing options for manufactured homes. Such properties have been significantly improved in terms of quality and amenities and, because they are pre-manufactured, they can quickly enter the supply chain.

- FHFA will authorize the Enterprises to take steps to expand the number of mortgages available for purchases of 2–4 unit properties that have an owner-occupant and renters. In so doing, it will be easier for prospective buyers to purchase and build wealth with these properties, and the supply of rental housing can expand as well.

Increasing the supply of multifamily housing is a cornerstone of the Administration’s plan to alleviate housing supply constraints. One proven way to do so is to increase the affordability of financing for building multiunit dwellings, particularly those targeted at low- and moderate-income renters.

- The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is a tax credit to builders of low-income housing that have a proven track record of increasing the supply of affordable rental units. The Enterprises will build on this record by raising their equity cap for LIHTC from $1 billion to $1.7 billion—from $500 million each to $850 million each.

- Treasury and HUD have formulated a plan to provide affordable financing from the Federal Financing Bank , which is tasked with buying, selling, and originating Federal loans and debt to State Housing Finance Agencies.

- Treasury is making $383 million in the Capital Magnet Fund available for the purpose of encouraging affordable housing production. The Capital Magnet Fund is a competitive grant program for Community Development Finance Institutions and non-profit housing groups.

Legislative Steps

The Administration urges Congress to invest in the construction of affordable housing units, incentivizing the relaxation of exclusionary zoning and helping income-burdened renters.According to HUD, these investments will add or rehabilitate approximately 2 million housing units nationally. In particular, these supply-side policies will:

- Construct or rehabilitate affordable rental housing units using Federal subsidies to support the financing, building, and maintenance of affordable rentals. This would be done principally by expanding the HOME Investment Partnership Program , the Housing Trust Fund , and the Capital Magnet Fund .

- Expand and strengthen LIHTC. As noted above, LIHTC has a proven track record of incentivizing the building of affordable multifamily units. The Administration has proposed to expand LIHTC and target some portion of additional allocations to areas that are particularly supply constrained.

- Build and rehabilitate homes for low- and middle-income homebuyers and homeowners. Based on the innovative and bipartisan Neighborhood Homes Investment Act , the Administration proposes a tax credit subsidy for building and rehabilitating homes for low- to middle-income homeowners living in economically vulnerable communities. Given racial disparities in home values, this proposal advances the Administration’s agenda on racial equity by boosting home values in economically distressed communities, which are disproportionately inhabited by people of color.

- Incentivize the removal of exclusionary zoning and harmful land use policies. One of the most persistent and binding constraints on housing supply is exclusionary zoning laws and practices. For decades, such laws have inflated housing costs, locking families out of areas with more opportunities. Along with working with State and local governments to reduce such restrictions, the Administration proposes the creation of an incentive program that awards flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to reduce barriers to affordable housing production.

There is no magic formula to quickly relieve the supply constraints described in this blog post. Shortages in housing stock along the entire price spectrum and their associated social and economic consequences have been building for decades. However, the proposals set forth by the Biden-Harris Administration—proposals we expect to create or rehabilitate over 2 million housing units—will make critical investments in our country’s housing infrastructure. By adding to the housing stock, and to the useful life of existing housing through rehabilitation investments, this is a once-in-a-generation effort to improve the lives of millions of Americans by making housing more plentiful and affordable.

[1] Low-cost units fall out of the inventory through demolition or are converted to higher-cost housing. It is difficult for the private market to replace low-cost units through new construction without subsidies or incentives, because the cost of constructing new units exceeds the ability of lower-income families to pay the unit cost. It does not “pencil out.”

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

There's a massive housing shortage across the U.S. Here's how bad it is where you live

Chris Arnold

Robert Benincasa

Jacqueline GaNun

Contractors work on the roof of a house under construction in Louisville, Ky. A new study shows the U.S. is 3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs. Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg via Getty Images hide caption

Contractors work on the roof of a house under construction in Louisville, Ky. A new study shows the U.S. is 3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs.

Danielle and Colin Lloyd spent the past year trying to buy a house in Atlanta, which went about as you'd expect these days.

"There is just nothing in this whole area, just nothing," says Danielle. The couple was looking for a place with at least a small yard and space for their three young kids.

"The prices were just ridiculous," says Colin. "People were just bidding much higher than what the house was listed for."

Danielle and Colin Lloyd spent much of the past year looking at homes in Atlanta but couldn't find anything they could afford. Danielle and Colin Lloyd hide caption

Danielle and Colin Lloyd spent much of the past year looking at homes in Atlanta but couldn't find anything they could afford.

"I only cried twice," Danielle chimes in.

Meanwhile, their landlord was about to raise their rent by $450 a month, which also was caused by the same problem — not enough homes to rent or buy.

"We're seeing a shortage, or housing underproduction, in all corners of the U.S.," says Mike Kingsella, the CEO of Up for Growth, which on Thursday released a study about the problem. The nonprofit research group is made up of affordable housing and industry groups.

"America's fallen 3.8 million homes short of meeting housing needs," he says. "And that's both rental housing and ownership."

Home prices are up more than 30% over the past couple of years, making homeownership unaffordable for millions of Americans. Rents are rising sharply too. The biggest culprit is this historic housing shortage. Strong demand and low supply mean higher prices.

Part of the problem goes back to the last housing crash, which happened around 2008. After that, many homebuilders went out of business, and economists say we didn't build enough for a decade.

So Up for Growth's study took a look at what's happening in 800 cities and towns.

"In Los Angeles, for instance, which is the most underproduced metro in the country, it's lacking 8.4% — nearly 400,000 homes missing across the region," Kingsella says. In other words, given the population of Los Angeles, there should be that many more units to meet the demand.

It's not just LA. In hundreds of big cities and small towns, from Boston to Boise, there's a housing shortage. But Kingsella says this is a solvable problem: "It doesn't have to be this way, is a key message coming out of this report."

Perhaps the biggest issue, he says, is that states and towns desperately need to change their zoning rules.

Changing outdated zoning rules is key

In Atlanta, Ernest Brown heads up the local chapter of housing advocacy organization YIMBY Action.

Ernest Brown heads up the Atlanta chapter of YIMBY Action, a housing advocacy organization. He says much of Atlanta is zoned for either big apartment towers downtown or single family homes. "There's nothing in between," he says. "We're really focused on what about those other options." Ernest Brown hide caption

Ernest Brown heads up the Atlanta chapter of YIMBY Action, a housing advocacy organization. He says much of Atlanta is zoned for either big apartment towers downtown or single family homes. "There's nothing in between," he says. "We're really focused on what about those other options."

"The YIMBY movement, which stands for 'yes in my backyard,' is kind of poking fun at the idea of NIMBY, 'not in my backyard,'" he says, referring to the long-standing issue of existing homeowners objecting to efforts to bring more affordable housing to their neighborhoods. Often they worry about greater density changing the character of the neighborhood or causing traffic and parking problems.

Brown says many places like Atlanta have outdated zoning rules that allow for either big apartment buildings downtown or single family homes on big lots — and nothing in between. He says that this results in a "missing middle" of more affordable town houses or smaller starter homes closer together.

Brown hears people complaining all the time about not being able to afford a house. He tries to get them to go to zoning meetings and call their representatives.

"They actually want to hear from you, particularly at the local level," he says. Brown says what he likes about the housing issue is that if you get involved, you're not just yelling into the wind about far-off federal politicians in Washington. Big changes have to happen at the state and local levels, he says.

"I have the phone number and regularly chat with my council person."

On this economists agree: We need more housing

There is some debate about just how bad the shortage is in terms of the number of homes the U.S. needs. Mark Zandi, the chief economist of Moody's Analytics, estimates the shortfall is closer to 1.6 million homes. He was not a part of this study.

"It's very difficult to know precisely what the shortage is," Zandi says. "But the bottom line is, no matter what the estimate is, it's a lot of homes that we're undersupplied." And he adds there's no doubt that many more homes need to be built to ensure that housing becomes more affordable, whether it's rental housing or homeownership.

You don't have to convince Andrea Iaroc of that. She works for nonprofit art museums and lived in Seattle for many years, where buying a house has long been very expensive. "It was just too much for me," she says.

Andrea Iaroc at the home she rents in Los Angeles. She says she may leave the U.S. and move to Colombia, where she has family, so she can afford to buy a house. Andrea Iaroc hide caption

Andrea Iaroc at the home she rents in Los Angeles. She says she may leave the U.S. and move to Colombia, where she has family, so she can afford to buy a house.

In 2019, she moved to Los Angeles: "I thought, 'OK, let me see what it looks like over here.'" But she still couldn't afford to buy a home. Iaroc has family in Colombia. So now she's seriously considering moving there and trying to work remotely, consulting for museums in the United States.

"I have some of my friends who are digital nomads, and they've done that," she says. "That used to be maybe Plan B. Now it's become Plan A."

Some cities and states are making changes

"I see firsthand the building political will mounting to take on and tackle this challenge," says Up for Growth's Kingsella. He points to California, Oregon and Maine, which all recently passed laws to end single family zoning by allowing for the construction of more than one home per parcel of land — for example , an in-law apartment over a garage or a backyard cottage. Kingsella expects more states to take similar actions in coming years as one way to help boost the supply of rental units.

Drive until you qualify

In other parts of the country, though, including Atlanta, such zoning reforms are still being voted down.

Danielle and Colin Lloyd did what many Americans have done over the years: look much farther away to find a place they can afford to buy. It's often called "drive until you qualify." And they just bought a house in Walnut Grove, Georgia.

"I told somebody at church, and she was like, 'Oh, my goodness, you all moved to Egypt — you're so far out!'" says Danielle.

The Lloyds finally found a home they could afford in Walnut Grove, Ga., for $409,000. They moved in two weeks ago. Danielle and Colin Lloyd hide caption

The Lloyds finally found a home they could afford in Walnut Grove, Ga., for $409,000. They moved in two weeks ago.

It's about an hour from where they used to live and work in Atlanta. They can both mostly work remotely, so they're not too worried about the commute.

They just moved in a couple of weeks ago. And they are feeling a little apprehensive about being an African American family moving from the city into a tiny rural town that is nearly 90% white, according to census data. There's a bit of a culture clash too.

"Moving to country Georgia where there's an ammo shop down the street, it's like a constant in your face," Danielle says.

But the couple says the neighbors seem friendly. There are other families with kids. So they're feeling hopeful.

"I love the idea of like when the kids are a little older saying, 'Yeah, go play at your friend's house.'" Danielle imagines what it will be like watching them run over to the neighbor's place: "I can see them, like, at the corner, you know. 'I'll watch you ride over there,'" she says. "I love that."

- rising cost of rent

- rental housing

- renting a home

- housing markt

- buy a house

- how to buy a house

- home ownership

- housing market

- Home prices

Tackling the world’s affordable housing challenge

Decent, affordable housing is fundamental to the health and well-being of people and to the smooth functioning of economies. Yet around the world, in developing and advanced economies alike, cities are struggling to meet that need. If current trends in urbanization and income growth persist, by 2025 the number of urban households that live in substandard housing—or are so financially stretched by housing costs that they forego other essentials, such as healthcare—could grow to 440 million, from 330 million. This could mean that the global affordable housing gap would affect one in three urban dwellers, about 1.6 billion people.

A new McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) report, A blueprint for addressing the global affordable housing challenge , defines the affordability gap as the difference between the cost of an acceptable standard housing unit (which varies by location) and what households can afford to pay using no more than 30 percent of income. The analysis draws on MGI’s Cityscope database of 2,400 metropolitan areas, as well as case studies from around the world. It finds that the affordable housing gap now stands at $650 billion a year and that the problem will only grow as urban populations expand: current trends suggest that there could be 106 million more low-income urban households by 2025, for example. To replace today’s inadequate housing and build the additional units needed by 2025 would require $9 trillion to $11 trillion in construction spending alone. With land, the total cost could be $16 trillion. Of this, we estimate that $1 trillion to $3 trillion may have to come from public funding.

However, four approaches used in concert could reduce the cost of affordable housing by 20 to 50 percent and substantially narrow the affordable housing gap by 2025. These largely market-oriented solutions—lowering the cost of land, construction, operations and maintenance, and financing—could make housing affordable for households earning 50 to 80 percent of median income.

Four approaches can narrow the housing-affordability gap by 20 to 50 percent.

- Unlocking land supply. Since land is usually the largest real-estate expense, securing it at appropriate locations can be the most effective way to reduce costs. In even the largest global cities, many parcels of land remain unoccupied or underused. Some of them may belong to government and could be released for development or sold to buy land for affordable housing. Private land can be brought forward for development through incentives such as density bonuses—increasing the permitted floor space on a plot of land and, therefore, its value; in return, the developer must provide land for affordable units.

- Reducing construction costs. While manufacturing and other industries have raised productivity steadily in the past few decades, in construction it has remained flat or gone down in many countries. Likewise, in many places residential housing is still built in the same way it was 50 years ago. Project costs could be reduced by about 30 percent and completion schedules shortened by about 40 percent if developers make use of value engineering (standardizing design) and industrial approaches, such as assembling buildings from prefabricated components manufactured off-site. Efficient procurement methods and other process improvements would help, as well. 1 1. For more on new construction techniques, see David Xu, “ How to build a skyscraper in two weeks ,” May 2014.

- Improved operations and maintenance. Twenty to 30 percent of the cost of housing is operations and maintenance. Energy-efficiency retrofits, such as insulation and new windows, can cut these costs. Maintenance expenses can be reduced by helping owners find qualified suppliers (through registration and licensing) and by consolidated purchasing. For example, buying consortia in the United Kingdom have saved 15 to 30 percent on some maintenance items for social housing.

- Lowering financing costs for buyers and developers. Improvements in underwriting would help banks safely make more housing loans to lower-income borrowers. Contractual savings programs can help such buyers accumulate down payments and therefore finance purchases with smaller and less risky loans. Such programs can also provide capital for low-interest mortgages to savers. Governments could help cut the financing costs of developers by making affordable housing projects less risky—for instance, by guaranteeing buyers or tenants for finished units.

The successful application of these approaches depends on creating an appropriate delivery platform for housing in each city. Policy makers, working with the private sector and local communities, need to set clear aspirations for housing throughout their cities. Critically, a minimum-standard housing unit must be defined in each of them. But an excessively ambitious minimum can discourage the construction of affordable homes and force more low-income households into informal housing. A better solution is to set standards that reflect rising aspirations—a housing “ladder” that can start with something very basic that might, for example, have communal kitchens and baths and serve as transitional housing for new arrivals.

Affordable housing could represent a significant opportunity for the global construction and housing-finance industries. Building homes for all the low-income households added in cities by 2025 could cost $2.3 trillion. That would represent a construction market of $200 billion to $250 billion in revenues annually, or about 10 percent of the global residential real-estate construction industry.

Lola Woetzel is a director of the McKinsey Global Institute, where Jan Mischke is a senior fellow; Sangeeth Ram is a principal in McKinsey’s Dubai office; Nicklas Garemo is a director in the Abu Dhabi office; and Shirish Sankhe is a director in the Mumbai office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Urban world: Cities and the rise of the consuming class

Urban world: Mapping the economic power of cities

Infrastructure productivity: How to save $1 trillion a year

Advertisement

Supported by

The Housing Shortage Isn’t Just a Coastal Crisis Anymore

An increasingly national problem has consequences for the quality of American family life, the economy and the future of housing politics.

- Share full article

By Emily Badger and Eve Washington

San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York and Washington have long failed to build enough housing to keep up with everyone trying to live there. And for nearly as long, other parts of the country have mostly been able to shrug off the housing shortage as a condition particular to big coastal cities.

But in the years leading up to the pandemic, that condition advanced around the country: Springfield, Mo., stopped having enough housing. And the same with Appleton, Wis., and Naples, Fla.

The housing shortage has spread to more parts of the country

What once seemed a blue-state coastal problem has increasingly become a national one, with consequences for the quality of life of American families, the health of the national economy and the politics of housing construction.

Today more families in the middle of America who could once count on becoming homeowners can’t be so confident anymore. And communities that long relied on their relatively affordable housing to draw new residents can no longer be so sure of that advantage.

“It’s like the cancer was limited to certain parts of our economic body,” said Sam Khater, the chief economist at Freddie Mac. “And now it’s spreading.”

Metros Without Enough Housing That Lost Big Surpluses

Estimated surplus or shortage of housing units, as a share of existing units.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Athens-Clarke County, Ga. | +12.0% | –2.4% |

Punta Gorda, Fla. | +7.7% | –1.3% |

Hilton Head Island-Bluffton, S.C. | +6.5% | –3.3% |

Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent, Fla. | +6.5% | –0.4% |

Cape Coral-Fort Myers, Fla. | +6.2% | –2.8% |

Muskegon, Mich. | +4.9% | –1.7% |

Auburn-Opelika, Ala. | +4.9% | –0.9% |

New Orleans-Metairie, La. | +4.4% | –1.6% |

Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, Nev. | +4.2% | –2.7% |

Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville, Fla. | +4.1% | –2.3% |

Yuma, Ariz. | +4.0% | –3.2% |

St. George, Utah | +3.8% | –3.0% |

Prescott Valley-Prescott, Ariz. | +3.7% | –2.8% |

Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, Fla. | +3.6% | –0.9% |

Kankakee, Ill. | +3.5% | –2.1% |

Metros With Big Shortages That Once Had Enough Housing

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Merced, Calif. | +1.9% | –8.7% |

Bend, Ore. | +2.1% | –8.2% |

Lakeland-Winter Haven, Fla. | +3.3% | –7.8% |

Stockton, Calif. | +0.0% | –6.6% |

Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler, Ariz. | +1.9% | –5.8% |

Vallejo, Calif. | +0.8% | –5.4% |

Coeur d'Alene, Idaho | +0.3% | –5.3% |

Fresno, Calif. | +0.1% | –5.2% |

Appleton, Wis. | +0.5% | –5.2% |

Racine, Wis. | +2.1% | –5.0% |

Green Bay, Wis. | +0.6% | –4.9% |

Naples-Marco Island, Fla. | +1.2% | –4.8% |

Sheboygan, Wis. | +0.2% | –4.5% |

Bakersfield, Calif. | +0.9% | –4.5% |

Yuba City, Calif. | +2.1% | –4.5% |

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This year’s State of the Nation’s Housing 2023 report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies paints a stark picture of record unaffordability, near-record housing shortages and major barriers to first-time homeownership.

LAWRENCE — The United States is experiencing a housing shortage. At least, that is the case according to common belief — and is even the basis for national policy, as the Biden administration has stated plans to address the housing supply shortfall.

Between 2019 and 2021, the shortage of homes affordable and available to renters with extremely low incomes worsened by more than 500,000 units, increasing from a shortage of 6.8 million to 7.3 million, and continuing a long-term trend of diminishing supply.

The Biden administration and housing experts link that squarely to a severe housing shortage that has helped drive up prices.

Housing starts as a share of the population decreased by roughly 39 percent in the 15-year period from January 2006 to June 2021. Researchers at Freddie Mac have estimated that the current shortage...

Home prices are up more than 30% over the past couple of years, making homeownership unaffordable for millions of Americans. Rents are rising sharply too. The biggest culprit is this historic ...

These largely market-oriented solutions—lowering the cost of land, construction, operations and maintenance, and financing—could make housing affordable for households earning 50 to 80 percent of median income.

Freddie Mac has estimated that the nation is short 3.8 million housing units to keep up with household formation. Up For Growth, a Washington-based policy and research group focused on the...

Without housing assistance, a family of four with poverty-level income could aford a monthly rent of no more than $655 in 2020, and many below the poverty level could not even aford that. The average cost of a modest two-bedroom rental home at the fair market rent, however, was $1,246 (NLIHC, 2020b).

In the U.S., only 36 rental homes are affordable and available for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. renter householders are seniors or have a disability, and another 44% are in the labor force, in school, or are single-adult caregivers.