Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Key Differences Between the Background of a Study and Literature Review

Don’t be too hard on yourself if you didn’t realize the study background and literature review were two distinct entities. The study background and literature review are both important parts of the research paper; however, due to their striking similarities, they are frequently confused with one another 1 . In this article, we will look at the key differences between the background of a study and literature review and how to write each section effectively.

When it comes to similarities between the study background and the literature review, both provide information about existing knowledge in a specific field by discussing various studies and developments. They almost always address gaps in the literature to contextualize the study at hand. So, how do they differ from one another? Simple answer: A literature review is an expanded version of the study background, or a study background is a condensed version of a literature review. To put it another way, “a study background is to a literature review what an abstract is to a paper.”

Differences between the background of the study and a literature review

Though the distinctions are subtle, understanding them is critical to avoiding confusion between these two elements. The following are the differences between the background of the study and a literature review:

- The background of a study is discussed at the beginning of the introduction while the literature review begins once the background of a study is completed (in the introduction section).

- The study background sets the stage for the study; the main goal of the study background is to effectively communicate the need for the study by highlighting the gaps in answering the open-ended questions. In contrast, a literature review is an in-depth examination of the relevant literature in that field in order to prepare readers for the study at hand . Furthermore, the literature review provides a broad overview of the topic to support the case for identifying gaps.

- The study background and literature review serve slightly different purposes; the study background emphasizes the significance of THE study, whereas the review of literature emphasizes advancement in the field by conducting a critical analysis of existing literature. It should be noted that a literature review also identifies gaps in the literature by comparing and analyzing various studies, but it is the study background that summarizes the critical findings that justifies the need for the research at hand.

- Another interesting difference is how they are structured; the study background structure follows a top-down approach, beginning with a discussion of a broader area and eventually narrowing down to a specific question—study problem—addressed in the study.

- The length of the background of the study and the literature review also differ, with the former being more concise and crisp and the latter being more detailed and elaborate.

Tips to effectively write the background of the study

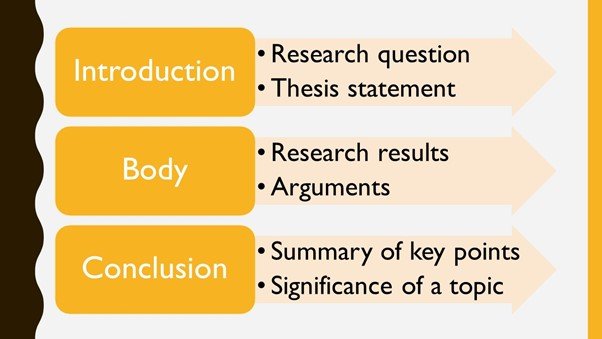

Writing the background of the study is sometimes a difficult undertaking for early career researchers; however, because this is an important component of the paper, it is critical that once write it clearly and accurately. The background must convey the context of the study, defining the need to conduct the current study 2 . The study background should be organized in such a way that it provides a historical perspective on the topic, while identifying the gaps that the current study aims to fill. If the topic is multidisciplinary, it should concisely address the relevant studies, laying the groundwork for the research question at hand. To put it simply, the researchers can follow the structure below:

- What is the state of the literature on the subject?

- Where are the gaps in the field?

- What is the importance of filling these gaps?

- What are the premises of your research?

The idea is to present the relevant studies to build the context without going into detail about each one; remember to keep it concise and direct. It is recommended that the findings be organized chronologically in order to trace the developments in the field and provide a snapshot of research advancements. The best way is to create an engaging story to pique readers’ interest in the topic by presenting sequential findings that led to YOUR research question. The flow should be such that each study prepares for the next while remaining in accordance with the central theme. However, the author should avoid common blunders such as inappropriate length (too long or too short), ambiguity, an unfocused theme, and disorganization.

Tips to write the literature review without mixing it up with the background of the study

As previously discussed in this article, the literature review is an extended version of the background of the study. It follows the background of the study and presents a detailed analysis of existing literature to support the background.

Authors must conduct a thorough research survey that includes various studies related to the broad topics of their research. Following an introduction to a broader topic, the literature review directs readers to relevant studies that are significant for the objectives of the present study.

The authors are advised to present the information thematically, preferably chronologically, for a better understanding of the readers from a wide range of disciplines. This arrangement provides a more complete picture of previous research, current focus, and future directions. Finally, there are two types of literature reviews that serve different purposes in papers; they are broadly classified as experimental and theoretical literature reviews. This, however, is a topic for another article.

We believe you can now easily distinguish between the study background and the literature review and understand how you can write them most effectively for your next study. Have fun writing!

References

- Qureshi, F. 6 Differences between Study Background and Literature Review. Editage Insights, May 3, 2019. https://www.editage.com/insights/6-differences-between-a-study-background-and-a-literature-review .

- Sachdev, R. How to Write the Background of Your Study. Editage Insights, November 27, 2018. https://www.editage.com/insights/how-to-write-the-background-of-your-study .

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Types of Literature Review — A Guide for Researchers

Table of Contents

Researchers often face challenges when choosing the appropriate type of literature review for their study. Regardless of the type of research design and the topic of a research problem , they encounter numerous queries, including:

What is the right type of literature review my study demands?

- How do we gather the data?

- How to conduct one?

- How reliable are the review findings?

- How do we employ them in our research? And the list goes on.

If you’re also dealing with such a hefty questionnaire, this article is of help. Read through this piece of guide to get an exhaustive understanding of the different types of literature reviews and their step-by-step methodologies along with a dash of pros and cons discussed.

Heading from scratch!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review provides a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on a particular topic, which is quintessential to any research project. Researchers employ various literature reviews based on their research goals and methodologies. The review process involves assembling, critically evaluating, and synthesizing existing scientific publications relevant to the research question at hand. It serves multiple purposes, including identifying gaps in existing literature, providing theoretical background, and supporting the rationale for a research study.

What is the importance of a Literature review in research?

Literature review in research serves several key purposes, including:

- Background of the study: Provides proper context for the research. It helps researchers understand the historical development, theoretical perspectives, and key debates related to their research topic.

- Identification of research gaps: By reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps or inconsistencies in knowledge, paving the way for new research questions and hypotheses relevant to their study.

- Theoretical framework development: Facilitates the development of theoretical frameworks by cultivating diverse perspectives and empirical findings. It helps researchers refine their conceptualizations and theoretical models.

- Methodological guidance: Offers methodological guidance by highlighting the documented research methods and techniques used in previous studies. It assists researchers in selecting appropriate research designs, data collection methods, and analytical tools.

- Quality assurance and upholding academic integrity: Conducting a thorough literature review demonstrates the rigor and scholarly integrity of the research. It ensures that researchers are aware of relevant studies and can accurately attribute ideas and findings to their original sources.

Types of Literature Review

Literature review plays a crucial role in guiding the research process , from providing the background of the study to research dissemination and contributing to the synthesis of the latest theoretical literature review findings in academia.

However, not all types of literature reviews are the same; they vary in terms of methodology, approach, and purpose. Let's have a look at the various types of literature reviews to gain a deeper understanding of their applications.

1. Narrative Literature Review

A narrative literature review, also known as a traditional literature review, involves analyzing and summarizing existing literature without adhering to a structured methodology. It typically provides a descriptive overview of key concepts, theories, and relevant findings of the research topic.

Unlike other types of literature reviews, narrative reviews reinforce a more traditional approach, emphasizing the interpretation and discussion of the research findings rather than strict adherence to methodological review criteria. It helps researchers explore diverse perspectives and insights based on the research topic and acts as preliminary work for further investigation.

Steps to Conduct a Narrative Literature Review

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-writing-a-narrative-review_fig1_354466408

Define the research question or topic:

The first step in conducting a narrative literature review is to clearly define the research question or topic of interest. Defining the scope and purpose of the review includes — What specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore? What are the main objectives of the research? Refine your research question based on the specific area you want to explore.

Conduct a thorough literature search

Once the research question is defined, you can conduct a comprehensive literature search. Explore and use relevant databases and search engines like SciSpace Discover to identify credible and pertinent, scholarly articles and publications.

Select relevant studies

Before choosing the right set of studies, it’s vital to determine inclusion (studies that should possess the required factors) and exclusion criteria for the literature and then carefully select papers. For example — Which studies or sources will be included based on relevance, quality, and publication date?

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Inclusion criteria are the factors a study must include (For example: Include only peer-reviewed articles published between 2022-2023, etc.). Exclusion criteria are the factors that wouldn’t be required for your search strategy (Example: exclude irrelevant papers, preprints, written in non-English, etc.)

Critically analyze the literature

Once the relevant studies are shortlisted, evaluate the methodology, findings, and limitations of each source and jot down key themes, patterns, and contradictions. You can use efficient AI tools to conduct a thorough literature review and analyze all the required information.

Synthesize and integrate the findings

Now, you can weave together the reviewed studies, underscoring significant findings such that new frameworks, contrasting viewpoints, and identifying knowledge gaps.

Discussion and conclusion

This is an important step before crafting a narrative review — summarize the main findings of the review and discuss their implications in the relevant field. For example — What are the practical implications for practitioners? What are the directions for future research for them?

Write a cohesive narrative review

Organize the review into coherent sections and structure your review logically, guiding the reader through the research landscape and offering valuable insights. Use clear and concise language to convey key points effectively.

Structure of Narrative Literature Review

A well-structured, narrative analysis or literature review typically includes the following components:

- Introduction: Provides an overview of the topic, objectives of the study, and rationale for the review.

- Background: Highlights relevant background information and establish the context for the review.

- Main Body: Indexes the literature into thematic sections or categories, discussing key findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks.

- Discussion: Analyze and synthesize the findings of the reviewed studies, stressing similarities, differences, and any gaps in the literature.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings of the review, identifies implications for future research, and offers concluding remarks.

Pros and Cons of Narrative Literature Review

- Flexibility in methodology and doesn’t necessarily rely on structured methodologies

- Follows traditional approach and provides valuable and contextualized insights

- Suitable for exploring complex or interdisciplinary topics. For example — Climate change and human health, Cybersecurity and privacy in the digital age, and more

- Subjectivity in data selection and interpretation

- Potential for bias in the review process

- Lack of rigor compared to systematic reviews

Example of Well-Executed Narrative Literature Reviews

Paper title: Examining Moral Injury in Clinical Practice: A Narrative Literature Review

Source: SciSpace

You can also chat with the papers using SciSpace ChatPDF to get a thorough understanding of the research papers.

While narrative reviews offer flexibility, academic integrity remains paramount. So, ensure proper citation of all sources and maintain a transparent and factual approach throughout your critical narrative review, itself.

2. Systematic Review

A systematic literature review is one of the comprehensive types of literature review that follows a structured approach to assembling, analyzing, and synthesizing existing research relevant to a particular topic or question. It involves clearly defined criteria for exploring and choosing studies, as well as rigorous methods for evaluating the quality of relevant studies.

It plays a prominent role in evidence-based practice and decision-making across various domains, including healthcare, social sciences, education, health sciences, and more. By systematically investigating available literature, researchers can identify gaps in knowledge, evaluate the strength of evidence, and report future research directions.

Steps to Conduct Systematic Reviews

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-Systematic-Literature-Review_fig1_321422320

Here are the key steps involved in conducting a systematic literature review

Formulate a clear and focused research question

Clearly define the research question or objective of the review. It helps to centralize the literature search strategy and determine inclusion criteria for relevant studies.

Develop a thorough literature search strategy

Design a comprehensive search strategy to identify relevant studies. It involves scrutinizing scientific databases and all relevant articles in journals. Plus, seek suggestions from domain experts and review reference lists of relevant review articles.

Screening and selecting studies

Employ predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to systematically screen the identified studies. This screening process also typically involves multiple reviewers independently assessing the eligibility of each study.

Data extraction

Extract key information from selected studies using standardized forms or protocols. It includes study characteristics, methods, results, and conclusions.

Critical appraisal

Evaluate the methodological quality and potential biases of included studies. Various tools (BMC medical research methodology) and criteria can be implemented for critical evaluation depending on the study design and research quetions .

Data synthesis

Analyze and synthesize review findings from individual studies to draw encompassing conclusions or identify overarching patterns and explore heterogeneity among studies.

Interpretation and conclusion

Interpret the findings about the research question, considering the strengths and limitations of the research evidence. Draw conclusions and implications for further research.

The final step — Report writing

Craft a detailed report of the systematic literature review adhering to the established guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). This ensures transparency and reproducibility of the review process.

By following these steps, a systematic literature review aims to provide a comprehensive and unbiased summary of existing evidence, help make informed decisions, and advance knowledge in the respective domain or field.

Structure of a systematic literature review

A well-structured systematic literature review typically consists of the following sections:

- Introduction: Provides background information on the research topic, outlines the review objectives, and enunciates the scope of the study.

- Methodology: Describes the literature search strategy, selection criteria, data extraction process, and other methods used for data synthesis, extraction, or other data analysis..

- Results: Presents the review findings, including a summary of the incorporated studies and their key findings.

- Discussion: Interprets the findings in light of the review objectives, discusses their implications, and identifies limitations or promising areas for future research.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main review findings and provides suggestions based on the evidence presented in depth meta analysis.

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Remember, the specific structure of your literature review may vary depending on your topic, research question, and intended audience. However, adhering to a clear and logical hierarchy ensures your review effectively analyses and synthesizes knowledge and contributes valuable insights for readers.

Pros and Cons of Systematic Literature Review

- Adopts rigorous and transparent methodology

- Minimizes bias and enhances the reliability of the study

- Provides evidence-based insights

- Time and resource-intensive

- High dependency on the quality of available literature (literature research strategy should be accurate)

- Potential for publication bias

Example of Well-Executed Systematic Literature Review

Paper title: Systematic Reviews: Understanding the Best Evidence For Clinical Decision-making in Health Care: Pros and Cons.

Read this detailed article on how to use AI tools to conduct a systematic review for your research!

3. Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review is a methodological review type of literature review that adopts an iterative approach to systematically map the existing literature on a particular topic or research area. It involves identifying, selecting, and synthesizing relevant papers to provide an overview of the size and scope of available evidence. Scoping reviews are broader in scope and include a diverse range of study designs and methodologies especially focused on health services research.

The main purpose of a scoping literature review is to examine the extent, range, and nature of existing studies on a topic, thereby identifying gaps in research, inconsistencies, and areas for further investigation. Additionally, scoping reviews can help researchers identify suitable methodologies and formulate clinical recommendations. They also act as the frameworks for future systematic reviews or primary research studies.

Scoping reviews are primarily focused on —

- Emerging or evolving topics — where the research landscape is still growing or budding. Example — Whole Systems Approaches to Diet and Healthy Weight: A Scoping Review of Reviews .

- Broad and complex topics : With a vast amount of existing literature.

- Scenarios where a systematic review is not feasible: Due to limited resources or time constraints.

Steps to Conduct a Scoping Literature Review

While Scoping reviews are not as rigorous as systematic reviews, however, they still follow a structured approach. Here are the steps:

Identify the research question: Define the broad topic you want to explore.

Identify Relevant Studies: Conduct a comprehensive search of relevant literature using appropriate databases, keywords, and search strategies.

Select studies to be included in the review: Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, determine the appropriate studies to be included in the review.

Data extraction and charting : Extract relevant information from selected studies, such as year, author, main results, study characteristics, key findings, and methodological approaches. However, it varies depending on the research question.

Collate, summarize, and report the results: Analyze and summarize the extracted data to identify key themes and trends. Then, present the findings of the scoping review in a clear and structured manner, following established guidelines and frameworks .

Structure of a Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review typically follows a structured format similar to a systematic review. It includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Introduce the research topic and objectives of the review, providing the historical context, and rationale for the study.

- Methods : Describe the methods used to conduct the review, including search strategies, study selection criteria, and data extraction procedures.

- Results: Present the findings of the review, including key themes, concepts, and patterns identified in the literature review.

- Discussion: Examine the implications of the findings, including strengths, limitations, and areas for further examination.

- Conclusion: Recapitulate the main findings of the review and their implications for future research, policy, or practice.

Pros and Cons of Scoping Literature Review

- Provides a comprehensive overview of existing literature

- Helps to identify gaps and areas for further research

- Suitable for exploring broad or complex research questions

- Doesn’t provide the depth of analysis offered by systematic reviews

- Subject to researcher bias in study selection and data extraction

- Requires careful consideration of literature search strategies and inclusion criteria to ensure comprehensiveness and validity.

In short, a scoping review helps map the literature on developing or emerging topics and identifying gaps. It might be considered as a step before conducting another type of review, such as a systematic review. Basically, acts as a precursor for other literature reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Scoping Literature Review

Paper title: Health Chatbots in Africa Literature: A Scoping Review

Check out the key differences between Systematic and Scoping reviews — Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

4. Integrative Literature Review

Integrative Literature Review (ILR) is a type of literature review that proposes a distinctive way to analyze and synthesize existing literature on a specific topic, providing a thorough understanding of research and identifying potential gaps for future research.

Unlike a systematic review, which emphasizes quantitative studies and follows strict inclusion criteria, an ILR embraces a more pliable approach. It works beyond simply summarizing findings — it critically analyzes, integrates, and interprets research from various methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) to provide a deeper understanding of the research landscape. ILRs provide a holistic and systematic overview of existing research, integrating findings from various methodologies. ILRs are ideal for exploring intricate research issues, examining manifold perspectives, and developing new research questions.

Steps to Conduct an Integrative Literature Review

- Identify the research question: Clearly define the research question or topic of interest as formulating a clear and focused research question is critical to leading the entire review process.

- Literature search strategy: Employ systematic search techniques to locate relevant literature across various databases and sources.

- Evaluate the quality of the included studies : Critically assess the methodology, rigor, and validity of each study by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter and select studies aligned with the research objectives.

- Data Extraction: Extract relevant data from selected studies using a structured approach.

- Synthesize the findings : Thoroughly analyze the selected literature, identify key themes, and synthesize findings to derive noteworthy insights.

- Critical appraisal: Critically evaluate the quality and validity of qualitative research and included studies by using BMC medical research methodology.

- Interpret and present your findings: Discuss the purpose and implications of your analysis, spotlighting key insights and limitations. Organize and present the findings coherently and systematically.

Structure of an Integrative Literature Review

- Introduction : Provide an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the integrative review.

- Methods: Describe the opted literature search strategy, selection criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present the synthesized findings, including key themes, patterns, and contradictions.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings about the research question, emphasizing implications for theory, practice, and prospective research.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main findings, limitations, and contributions of the integrative review.

Pros and Cons of Integrative Literature Review

- Informs evidence-based practice and policy to the relevant stakeholders of the research.

- Contributes to theory development and methodological advancement, especially in the healthcare arena.

- Integrates diverse perspectives and findings

- Time-consuming process due to the extensive literature search and synthesis

- Requires advanced analytical and critical thinking skills

- Potential for bias in study selection and interpretation

- The quality of included studies may vary, affecting the validity of the review

Example of Integrative Literature Reviews

Paper Title: An Integrative Literature Review: The Dual Impact of Technological Tools on Health and Technostress Among Older Workers

5. Rapid Literature Review

A Rapid Literature Review (RLR) is the fastest type of literature review which makes use of a streamlined approach for synthesizing literature summaries, offering a quicker and more focused alternative to traditional systematic reviews. Despite employing identical research methods, it often simplifies or omits specific steps to expedite the process. It allows researchers to gain valuable insights into current research trends and identify key findings within a shorter timeframe, often ranging from a few days to a few weeks — unlike traditional literature reviews, which may take months or even years to complete.

When to Consider a Rapid Literature Review?

- When time impediments demand a swift summary of existing research

- For emerging topics where the latest literature requires quick evaluation

- To report pilot studies or preliminary research before embarking on a comprehensive systematic review

Steps to Conduct a Rapid Literature Review

- Define the research question or topic of interest. A well-defined question guides the search process and helps researchers focus on relevant studies.

- Determine key databases and sources of relevant literature to ensure comprehensive coverage.

- Develop literature search strategies using appropriate keywords and filters to fetch a pool of potential scientific articles.

- Screen search results based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Extract and summarize relevant information from the above-preferred studies.

- Synthesize findings to identify key themes, patterns, or gaps in the literature.

- Prepare a concise report or a summary of the RLR findings.

Structure of a Rapid Literature Review

An effective structure of an RLR typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Briefly introduce the research topic and objectives of the RLR.

- Methodology: Describe the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present a summary of the findings, including key themes or patterns identified.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings, discuss implications, and highlight any limitations or areas for further research

- Conclusion: Summarize the key findings and their implications for practice or future research

Pros and Cons of Rapid Literature Review

- RLRs can be completed quickly, authorizing timely decision-making

- RLRs are a cost-effective approach since they require fewer resources compared to traditional literature reviews

- Offers great accessibility as RLRs provide prompt access to synthesized evidence for stakeholders

- RLRs are flexible as they can be easily adapted for various research contexts and objectives

- RLR reports are limited and restricted, not as in-depth as systematic reviews, and do not provide comprehensive coverage of the literature compared to traditional reviews.

- Susceptible to bias because of the expedited nature of RLRs. It would increase the chance of overlooking relevant studies or biases in the selection process.

- Due to time constraints, RLR findings might not be robust enough as compared to systematic reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Rapid Literature Review

Paper Title: What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature

A Summary of Literature Review Types

Literature Review Type | Narrative | Systematic | Integrative | Rapid | Scoping |

Approach | The traditional approach lacks a structured methodology | Systematic search, including structured methodology | Combines diverse methodologies for a comprehensive understanding | Quick review within time constraints | Preliminary study of existing literature |

How Exhaustive is the process? | May or may not be comprehensive | Exhaustive and comprehensive search | A comprehensive search for integration | Time-limited search | Determined by time or scope constraints |

Data Synthesis | Narrative | Narrative with tabular accompaniment | Integration of various sources or methodologies | Narrative and tabular | Narrative and tabular |

Purpose | Provides description of meta analysis and conceptualization of the review | Comprehensive evidence synthesis | Holistic understanding | Quick policy or practice guidelines review | Preliminary literature review |

Key characteristics | Storytelling, chronological presentation | Rigorous, traditional and systematic techniques approach | Diverse source or method integration | Time-constrained, systematic approach | Identifies literature size and scope |

Example Use Case | Historical exploration | Effectiveness evaluation | Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed combination | Policy summary | Research literature overview |

Tools and Resources for Conducting Different Types of Literature Reviews

Online scientific databases.

Platforms such as SciSpace , PubMed , Scopus , Elsevier , and Web of Science provide access to a vast array of scholarly literature, facilitating the search and data retrieval process.

Reference management software

Tools like SciSpace Citation Generator , EndNote, Zotero , and Mendeley assist researchers in organizing, annotating, and citing relevant literature, streamlining the review process altogether.

Automate Literature Review with AI tools

Automate the literature review process by using tools like SciSpace literature review which helps you compare and contrast multiple papers all on one screen in an easy-to-read matrix format. You can effortlessly analyze and interpret the review findings tailored to your study. It also supports the review in 75+ languages, making it more manageable even for non-English speakers.

Goes without saying — literature review plays a pivotal role in academic research to identify the current trends and provide insights to pave the way for future research endeavors. Different types of literature review has their own strengths and limitations, making them suitable for different research designs and contexts. Whether conducting a narrative review, systematic review, scoping review, integrative review, or rapid literature review, researchers must cautiously consider the objectives, resources, and the nature of the research topic.

If you’re currently working on a literature review and still adopting a manual and traditional approach, switch to the automated AI literature review workspace and transform your traditional literature review into a rapid one by extracting all the latest and relevant data for your research!

There you go!

Frequently Asked Questions

Narrative reviews give a general overview of a topic based on the author's knowledge. They may lack clear criteria and can be biased. On the other hand, systematic reviews aim to answer specific research questions by following strict methods. They're thorough but time-consuming.

A systematic review collects and analyzes existing research to provide an overview of a topic, while a meta-analysis statistically combines data from multiple studies to draw conclusions about the overall effect of an intervention or relationship between variables.

A systematic review thoroughly analyzes existing research on a specific topic using strict methods. In contrast, a scoping review offers a broader overview of the literature without evaluating individual studies in depth.

A systematic review thoroughly examines existing research using a rigorous process, while a rapid review provides a quicker summary of evidence, often by simplifying some of the systematic review steps to meet shorter timelines.

A systematic review carefully examines many studies on a single topic using specific guidelines. Conversely, an integrative review blends various types of research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

You might also like

标题 :人工智能在系统文献综述中的作用

Papel de la IA en la revisión sistemática de la literatura

Rôle de l'IA dans l'analyse systématique de la littérature

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Librarian Assistance

For help, please contact the librarian for your subject area. We have a guide to library specialists by subject .

- Last Updated: Aug 26, 2024 5:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

What Is A Literature Review?

A plain-language explainer (with examples).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | June 2020 (Updated May 2023)

If you’re faced with writing a dissertation or thesis, chances are you’ve encountered the term “literature review” . If you’re on this page, you’re probably not 100% what the literature review is all about. The good news is that you’ve come to the right place.

Literature Review 101

- What (exactly) is a literature review

- What’s the purpose of the literature review chapter

- How to find high-quality resources

- How to structure your literature review chapter

- Example of an actual literature review

What is a literature review?

The word “literature review” can refer to two related things that are part of the broader literature review process. The first is the task of reviewing the literature – i.e. sourcing and reading through the existing research relating to your research topic. The second is the actual chapter that you write up in your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s look at each of them:

Reviewing the literature

The first step of any literature review is to hunt down and read through the existing research that’s relevant to your research topic. To do this, you’ll use a combination of tools (we’ll discuss some of these later) to find journal articles, books, ebooks, research reports, dissertations, theses and any other credible sources of information that relate to your topic. You’ll then summarise and catalogue these for easy reference when you write up your literature review chapter.

The literature review chapter

The second step of the literature review is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or thesis structure ). At the simplest level, the literature review chapter is an overview of the key literature that’s relevant to your research topic. This chapter should provide a smooth-flowing discussion of what research has already been done, what is known, what is unknown and what is contested in relation to your research topic. So, you can think of it as an integrated review of the state of knowledge around your research topic.

What’s the purpose of a literature review?

The literature review chapter has a few important functions within your dissertation, thesis or research project. Let’s take a look at these:

Purpose #1 – Demonstrate your topic knowledge

The first function of the literature review chapter is, quite simply, to show the reader (or marker) that you know what you’re talking about . In other words, a good literature review chapter demonstrates that you’ve read the relevant existing research and understand what’s going on – who’s said what, what’s agreed upon, disagreed upon and so on. This needs to be more than just a summary of who said what – it needs to integrate the existing research to show how it all fits together and what’s missing (which leads us to purpose #2, next).

Purpose #2 – Reveal the research gap that you’ll fill

The second function of the literature review chapter is to show what’s currently missing from the existing research, to lay the foundation for your own research topic. In other words, your literature review chapter needs to show that there are currently “missing pieces” in terms of the bigger puzzle, and that your study will fill one of those research gaps . By doing this, you are showing that your research topic is original and will help contribute to the body of knowledge. In other words, the literature review helps justify your research topic.

Purpose #3 – Lay the foundation for your conceptual framework

The third function of the literature review is to form the basis for a conceptual framework . Not every research topic will necessarily have a conceptual framework, but if your topic does require one, it needs to be rooted in your literature review.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the drivers of a certain outcome – the factors which contribute to burnout in office workers. In this case, you’d likely develop a conceptual framework which details the potential factors (e.g. long hours, excessive stress, etc), as well as the outcome (burnout). Those factors would need to emerge from the literature review chapter – they can’t just come from your gut!

So, in this case, the literature review chapter would uncover each of the potential factors (based on previous studies about burnout), which would then be modelled into a framework.

Purpose #4 – To inform your methodology

The fourth function of the literature review is to inform the choice of methodology for your own research. As we’ve discussed on the Grad Coach blog , your choice of methodology will be heavily influenced by your research aims, objectives and questions . Given that you’ll be reviewing studies covering a topic close to yours, it makes sense that you could learn a lot from their (well-considered) methodologies.

So, when you’re reviewing the literature, you’ll need to pay close attention to the research design , methodology and methods used in similar studies, and use these to inform your methodology. Quite often, you’ll be able to “borrow” from previous studies . This is especially true for quantitative studies , as you can use previously tried and tested measures and scales.

How do I find articles for my literature review?

Finding quality journal articles is essential to crafting a rock-solid literature review. As you probably already know, not all research is created equally, and so you need to make sure that your literature review is built on credible research .

We could write an entire post on how to find quality literature (actually, we have ), but a good starting point is Google Scholar . Google Scholar is essentially the academic equivalent of Google, using Google’s powerful search capabilities to find relevant journal articles and reports. It certainly doesn’t cover every possible resource, but it’s a very useful way to get started on your literature review journey, as it will very quickly give you a good indication of what the most popular pieces of research are in your field.

One downside of Google Scholar is that it’s merely a search engine – that is, it lists the articles, but oftentimes it doesn’t host the articles . So you’ll often hit a paywall when clicking through to journal websites.

Thankfully, your university should provide you with access to their library, so you can find the article titles using Google Scholar and then search for them by name in your university’s online library. Your university may also provide you with access to ResearchGate , which is another great source for existing research.

Remember, the correct search keywords will be super important to get the right information from the start. So, pay close attention to the keywords used in the journal articles you read and use those keywords to search for more articles. If you can’t find a spoon in the kitchen, you haven’t looked in the right drawer.

Need a helping hand?

How should I structure my literature review?

Unfortunately, there’s no generic universal answer for this one. The structure of your literature review will depend largely on your topic area and your research aims and objectives.

You could potentially structure your literature review chapter according to theme, group, variables , chronologically or per concepts in your field of research. We explain the main approaches to structuring your literature review here . You can also download a copy of our free literature review template to help you establish an initial structure.

In general, it’s also a good idea to start wide (i.e. the big-picture-level) and then narrow down, ending your literature review close to your research questions . However, there’s no universal one “right way” to structure your literature review. The most important thing is not to discuss your sources one after the other like a list – as we touched on earlier, your literature review needs to synthesise the research , not summarise it .

Ultimately, you need to craft your literature review so that it conveys the most important information effectively – it needs to tell a logical story in a digestible way. It’s no use starting off with highly technical terms and then only explaining what these terms mean later. Always assume your reader is not a subject matter expert and hold their hand through a journe y of the literature while keeping the functions of the literature review chapter (which we discussed earlier) front of mind.

Example of a literature review

In the video below, we walk you through a high-quality literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction. This will give you a clearer view of what a strong literature review looks like in practice and hopefully provide some inspiration for your own.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we’ve (hopefully) answered the question, “ what is a literature review? “. We’ve also considered the purpose and functions of the literature review, as well as how to find literature and how to structure the literature review chapter. If you’re keen to learn more, check out the literature review section of the Grad Coach blog , as well as our detailed video post covering how to write a literature review .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

16 Comments

Thanks for this review. It narrates what’s not been taught as tutors are always in a early to finish their classes.

Thanks for the kind words, Becky. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This website is amazing, it really helps break everything down. Thank you, I would have been lost without it.

This is review is amazing. I benefited from it a lot and hope others visiting this website will benefit too.

Timothy T. Chol [email protected]

Thank you very much for the guiding in literature review I learn and benefited a lot this make my journey smooth I’ll recommend this site to my friends

This was so useful. Thank you so much.

Hi, Concept was explained nicely by both of you. Thanks a lot for sharing it. It will surely help research scholars to start their Research Journey.

The review is really helpful to me especially during this period of covid-19 pandemic when most universities in my country only offer online classes. Great stuff

Great Brief Explanation, thanks

So helpful to me as a student

GradCoach is a fantastic site with brilliant and modern minds behind it.. I spent weeks decoding the substantial academic Jargon and grounding my initial steps on the research process, which could be shortened to a couple of days through the Gradcoach. Thanks again!

This is an amazing talk. I paved way for myself as a researcher. Thank you GradCoach!

Well-presented overview of the literature!

This was brilliant. So clear. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Writing Research Background

Research background is a brief outline of the most important studies that have been conducted so far presented in a chronological order. Research background part in introduction chapter can be also headed ‘Background of the Study.” Research background should also include a brief discussion of major theories and models related to the research problem.

Specifically, when writing research background you can discuss major theories and models related to your research problem in a chronological order to outline historical developments in the research area. When writing research background, you also need to demonstrate how your research relates to what has been done so far in the research area.

Research background is written after the literature review. Therefore, literature review has to be the first and the longest stage in the research process, even before the formulation of research aims and objectives, right after the selection of the research area. Once the research area is selected, the literature review is commenced in order to identify gaps in the research area.

Research aims and objectives need to be closely associated with the elimination of this gap in the literature. The main difference between background of the study and literature review is that the former only provides general information about what has been done so far in the research area, whereas the latter elaborates and critically reviews previous works.

John Dudovskiy

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Let’s get to it! What should I do before writing the literature review?

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

Keep in mind that UNC Libraries have research guides and to databases relevant to many fields of study. You can reach out to the subject librarian for a consultation: https://library.unc.edu/support/consultations/ .

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing the literature review

Find a focus.

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Convey it to your reader

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine. More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Organizing the body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review: