- Letter from the Directors

- Health Topics

- Contact CIDI

- Active Studies

- Research Networks

- COVID-19 Grand Rounds

- Clinical Case Discussions

- Innovations

- Current Efforts

- Clinical Case Discussions and Video Conference Archive

- Field Study In India

- Research Elective at JHU

- Forms & Resources

- Current Scholars

- Former Scholars

- Publications

- About this Site

- Support CIDI

- India Campaign

Sangita Shelke, MD: Preventive and Social Medicine; Diplomas in Nutrition, Hospital Administration, Psychological counseling

MBBS- S.R.T.R Medical College, Ambejogai, Marathwada University, Maharashtra, Dec- 1990. MD- Preventive and Social Medicine, Government Medical College, Aurangabad. Marathwada University, Maharashtra, Dec- 1994. PG DHA- Diploma in Hospital Administration, Society for Development and education Coimbatore, Dec 1997. PG DND- Diploma in Nutrition and Dietetics, Society for Development and education Coimbatore, Dec 1998. PG DPC- Diploma in Psychological Counselling, Society for Development and education Coimbatore, May 1999. Have done course in Clinical Trials from CMC Vellore Dec- 2009. Honors and Awards:

Passed MD-PSM, Diploma in Hospital Administration, Diploma in Nutrition and Dietetics, Psychological Counselling all exams with DISTINCTION. Research paper “Husbands commitment in safe motherhood” presented in international conference on women and child health held at Rural Medical College Loni. Nov 1998 and was awarded prize of best paper. presented research paper “ A study on female Tamasha artists from pune district.” In Annual research conference of B.J.Medical College Pune 2006 and was awarded first prize.

Research Interests: Indeed TB is a social disease with so many social problems especially the women suffering from TB/HIV undergoes a pathetic life situation. Women are silent suffers, of both HIV and TB in male dominated society of India. My ultimate desire is if I can make a difference in the lives of these silent suffers. My research interests include understanding the factors that improve overall levels and distribution of health status of women. My research interest also includes operational research and health system research. I am also interested in finding out various ways in which defaulters and drug resistant can be minimised.

- Studies/Projects

Characterization of TB-specific T Cell Responses in Highly-exposed, but Uninfected Health Care Workers in India

Assessing the impact of psychosocial involvement in health care workers with and without active tuberculosis at the byramjee jeejeebhoy government medical college, pune, india, perceptions of hcws on barriers and opportunities to airborne infection control guideline implementation, utility of the interferon-gamma release assay for latent tuberculosis infection screening among indian health-care workers.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case study ďavid health and social care

Birch View is a residential care home in Wales. It caters for older people, lots of whom have dementia. Many of the individuals living in Birch View speak Welsh and the home tries to employ care and support workers who speak both Welsh and English. Birch View aims to treat all individuals living in the home with dignity and respect and provide services that help them achieve their personal outcomes and what matters to them, for example knowing what time they like to get up and go to bed, when they like to eat their meals and the type of food that they enjoy, what their hobbies and interests are and how they would like to stay in touch with family and friends. The home is welcoming and has lots of different activities such as: • An art club • Singing for pleasure • Film and book clubs • A gardening group • Keep fit sessions e.g. chair-based exercises The home has an activities co-ordinator who organises the clubs and groups, she is always keen to hear from the individuals living at Birch View about their interests or what they would like to try. The activities co-ordinator has resources for the clubs and groups including computer tablets that can be used to watch films for the film club. Birch View involves the local community in the home including: • Visits from school children • Weekly hairdresser • Monthly visiting Chapel Service • Visits from people with their pets • Visits to events in the local town David has recently moved into Birch View, he is 88 years old and speaks Welsh as his first language. David has been diagnosed with dementia. Until recently, David lived at home with his wife Gwen who is 85 years old. He was supported by Gwen, health and social care services and their son and daughter who both live locally, have families of their own and work full time. David has become more confused recently, he is becoming muddled between night and day and Gwen has found him wandering outside in the middle of the night. He is struggling to access the bathroom in the house, is having difficulties with continence and has had a number of falls; after the last fall he was admitted to hospital where he was treated for minor injuries. Before he was discharged from hospital, an assessment was completed with David, Gwen, their son and daughter by social services and health professionals. This included a mental capacity and best-interest assessment. It was agreed that it was in David’s best interest for him to move into a residential care home as it was no longer safe for him to stay at home. Gwen, their children and grandchildren visit him regularly. 48 David has been given a walking frame to use at Birch View but forgets to use it. Since moving into Birch View, he has become more unstable, he has fallen twice and struggles to get in and out of bed. The care and support workers have reported that he seems agitated and confused, is not sleeping well, is trying to get out of bed in the night and has little appetite. David’s family and the care and support workers are worried that he is not settling in and is struggling more with his mobility. Nicole is one of the care and support workers at Birch View, she has noticed that David tends to be more confused in the mornings but is clearer in the afternoons. This information has been recorded in his personal plan to support his communication. Nicole is working with David and his family to find out more about his interests and background. Gwen tells her that before he became unwell, he was very active, walking the dog daily and gardening. She says that he loved growing vegetables and had been a vegetarian for the past 30 years. He was a history teacher and used to belong to the local history club at the library, he loved reading and enjoyed watching old war films. He spent a lot of time with the grandchildren as they were growing up, spending time with them in the garden, planting seeds and growing plants in their own little plots on his vegetable patch. Nicole explains to Gwen that even though David’s personal plan says that he is a vegetarian, he has been choosing the meat option from the lunch time menu and then not eating it. The care and support workers are offering David vegetarian food options but he is refusing these. Nicole asks Gwen for some ideas of the type of food that David enjoyed when he was living at home as she is worried that he is not eating enough and this may be affecting him. Nicole arranges for David to meet the activities co-ordinator in the afternoon when he is less confused and more able to express what he wants. Having spoken to Gwen and David, she thinks that he may enjoy the gardening group and film club and wonders whether they could arrange for one of his favourite war films to be shown to get him interested. Describe one method used by Birch View to meet David’s communication needs. The decline in David’s mobility has the potential to impact upon his well-being. a. State two potential impacts of this on his physical well-being. State two potential impacts on his mental well-being Explain how the principles of the Mental Capacity Act have been applied in supporting David’s health and well-being.

RELATED PAPERS

Betty Ssali

thenji bhebhe

The British Journal of Psychiatry

Ogbonna Amanze

Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment

Roberta R Greene

BMJ (Clinical research ed.)

David Nunan

Tony Schumacher Jones

Piers Gooding , Cher Nicholson

Robin Balbernie

julie ridley

Akinola Akinyemi

Health & Social Care in the Community

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health

Kathryn Refshauge

Paul Spicker

Mayada Darfour

International Journal of Leadership in Public Services

Sylvia Elaine

spsw.ox.ac.uk

Giuliana Costa

Sue Yeandle

Val Williams

Michal Synek

Jakki Cowley

David Cobley

Health and social care level 3

Emma Stevens

Gary Lashko

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 02 September 2024

Sustaining the mobile medical units to bring equity in healthcare: a PLS-SEM approach

- Jignesh Patel 1 ,

- Sangita More 1 ,

- Pravin Sohani 1 ,

- Shrinath Bedarkar 1 ,

- Kamala Kannan Dinesh 2 ,

- Deepika Sharma 3 ,

- Sanjay Dhir 3 ,

- Sushil Sushil 3 ,

- Gunjan Taneja 4 &

- Raj Shankar Ghosh 5

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 23 , Article number: 175 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Equitable access to healthcare for rural, tribal, and underprivileged people has been an emerging area of interest for researchers, academicians, and policymakers worldwide. Improving equitable access to healthcare requires innovative interventions. This calls for clarifying which operational model of a service innovation needs to be strengthened to achieve transformative change and bring sustainability to public health interventions. The current study aimed to identify the components of an operational model of mobile medical units (MMUs) as an innovative intervention to provide equitable access to healthcare.

The study empirically examined the impact of scalability, affordability, replicability (SAR), and immunization performance on the sustainability of MMUs to develop a framework for primary healthcare in the future. Data were collected via a survey answered by 207 healthcare professionals from six states in India. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was conducted to empirically determine the interrelationships among various constructs.

The standardized path coefficients revealed that three factors (SAR) significantly influenced immunization performance as independent variables. Comparing the three hypothesized relationships demonstrates that replicability has the most substantial impact, followed by scalability and affordability. Immunization performance was found to have a significant direct effect on sustainability. For evaluating sustainability, MMUs constitute an essential component and an enabler of a sustainable healthcare system and universal health coverage.

This study equips policymakers and public health professionals with the critical components of the MMU operational model leading toward sustainability. The research framework provides reliable grounds for examining the impact of scalability, affordability, and replicability on immunization coverage as the primary public healthcare outcome.

As India advances towards universal healthcare with substantial improvements in coverage, addressing marginalized communities remains a persistent concern for the current healthcare system [ 1 , 2 ]. Many improvements have been made to India's healthcare system as a result of the country's successful efforts to address a wide range of challenges, such as unequal access to treatment, a dearth of high-quality medical services, and inaccurate information [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Hesitancy, social stigma, ignorance, and a shortage of medical professionals have all contributed to these difficulties and served as roadblocks to enhancing access to healthcare for India's rural, tribal, and underprivileged people [ 7 , 8 ]. Therefore, it is imperative to implement broad innovative interventions in India's current primary healthcare system to address these issues and advance universal health coverage.

In this context, mobile medical units (MMUs) have a tremendous potential to provide equal and effective access to various healthcare facilities, including immunization clinics for the disadvantaged and immunocompromised population [ 9 , 10 ]. For communities cut off from mainstream services due to climatic conditions, geography, and social stigma, MMUs can be essential for providing service to immunocompromised, vulnerable, and marginalized people living in remote and challenging places [ 11 , 12 ].

Research indicates that MMUs have been crucial in delivering specialized healthcare services in addition to primary healthcare in rural regions [ 13 , 14 ]. Also, research has indicated that MMUs are particularly effective in delivering health care to India's underprivileged and neglected communities [ 15 ]. Hence, MMUs appear promising in remote areas where local health services lack the necessary resources. MMUs can provide primary healthcare services in locations lacking or with insufficient established facilities and specialized service delivery [ 16 ].

Mobile units, especially in certain areas of emergency and preventive medicine, have shown considerable potential in rural regions, but MMUs should not be adopted without careful assessment. The effective execution and long-term sustainability of this intervention depend on evaluating the critical elements of the operational model for MMUs. While numerous studies have highlighted the role of mobile medical units (MMUs) in increasing healthcare accessibility, especially in remote and underserved areas, there is a limited understanding of the specific operational models adopted by these units and their impact on healthcare outcomes [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The diversity in operational strategies, ranging from the type of services offered, staffing models, technological integration, to partnership networks, remains largely unexplored. Furthermore, while the immediate benefits of MMUs, such as increased healthcare access, are well-documented, there is a paucity of research examining the long-term impact of these units on healthcare outcomes along with the impact on sustaining these models for delivering other primary healthcare services. To improve the operational model for the future and provide a framework for policy analysis, it is crucial to comprehend the impacts of operational model components on primary healthcare outcomes and the model’s sustainability. Therefore, this study aims to achieve the following research objectives:

RO1 . To empirically determine the potential impact of scalability, affordability, replicability, and immunization performance on the sustainability of the MMUs operational model.

RO2 . To develop a framework of MMUs for future innovations in primary healthcare.

This study will empirically analyze the operational model of MMUs to confirm the impact on performance and sustainability. Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Karnataka, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu have been selected as the sample states where the where the case organization has been operationally implemented and subjected to a thorough evaluation of these factors. The relay of work can be used to revisit the components of the operational model for MMUs by the practitioners and policymakers. The theoretical underpinnings of this study are presented in the following sub-sections, along with the hypotheses developed for empirical validation.

Scalability

Various studies have identified scalability as a prominent driver for improving healthcare outcomes [ 17 , 18 ]. Scalability is often associated with sustainability and higher performance in terms of efficiency and increased immunization coverage. Scalability in regard to a healthcare intervention refers to its potential suitability for scaling up. It is essential to have a clear understanding of the term ‘scalability’ in the context of public health to develop an effective health promotion intervention. Various studies have been conducted to explore the indicators for accurately measuring the scalability of public health interventions and examining their impact on health outcomes, such as immunization coverage and performance [ 19 , 20 ]. In this study we measured scalability by examining the delivery system, the availability of technical assistance, the organizational capacity, management, financial support, and partnerships.

Aspects like a delivery system that would ensure the reach and expansion of mobile clinics are essential components of an efficient strategy. Similarly, technology plays a significant role in the seamless dispersal of the immunization program, and a technical assistant helps blur the lines between the digital and physical worlds. Such integration keeps the delivery of vaccines, scheduling of vaccination drives, and other logistical concerns in check and ensures accountability with regard to the number of individuals immunized [ 21 ]. Another component that influences scalability is the organizational capacity of the stakeholders, for example in the mobile clinics employed in the COVID-19 vaccination drive. Mapping various areas of coordination and utilizing the organizational capacity for various operational purposes has helped mobile clinics to achieve their immunization targets. Advanced planning, timely delivery of vaccines, transportation, securing of awareness creation, mobilization of beneficiaries, proper registration, safe vaccination, and dispersal of certificates were crucial for critical ordination. All the elements discussed above require decision support as well as financial support. Decision support should focus on the inclusiveness of the tribal areas for immunization programs [ 22 ]. Similarly, financial support was also directed toward achieving immunization targets for the marginalized population, including tribal people, daily wage workers, street vendors, sex workers, etc. [ 23 ]. The partnership between mobile clinics and government agencies led to the creation of robust and scalable processes that integrated infrastructural and digital spaces for the successful deployment of a vaccine program [ 7 ].

Affordability

Affordability is essential for the government to provide healthcare services to ensure vaccines for all. Especially in a developing country like India, which comprises a large population, where health budgets have to be outlined judiciously [ 24 ]. Specific mechanisms are needed to ensure sustainable financing of vaccines available to individuals from marginalized populations [ 25 ]. The ability of mobile clinics to cover the hard-to-reach parts of the state was made possible only because of well-planned transportation by a network of ambulances. Close management of the transportation costs was of immediate need as the goal of the program was to bring a mobile clinic within reach of everyone to vaccinate the marginalized population [ 3 ]. Vaccination procurement and allocation were done appropriately by the government agencies to smoothly execute the plan [ 8 ].

Consideration was not limited to transportation costs, however, and the mobile clinic’s team was also concerned about limiting waste as the vaccine solutions have a shelf-life of around four hours after opening. Keeping the vaccine cold to limit waste helped to cut down the cost of the vaccine and increase affordability [ 26 ]. Strong coordination was needed between the mobile clinics’ team and government agencies to monitor and regulate the deployment of vaccines once they were removed from cold storage [ 8 ]. The other aspect that was required to be regulated at this scale was the direct and indirect costs of providing a robust infrastructure, including arrangements for transporting elderly and disabled people, and creating awareness in the population of the critical importance of getting the second dose [ 27 ].

Replicability

Replicability of the mobile clinic model is also one more way to guarantee a faster and higher coverage of target population immunization. This would include clear and transparent communication on the part of government agencies regarding dedicated timelines, prioritization of the groups to be vaccinated first, the types of vaccine, and the vaccination schedules [ 28 ]. Training accredited social health activists, doctors, data operators, and other directly involved workers are also part of the replicability strategy. Common aspects of such strategies include developing awareness and vaccination knowledge, acquiring the means to engage the community through open-sourcing strategic partnerships with influential local leaders to build confidence and trust for the medical community regarding the safety of the vaccine, preventing the spread of misinformation and rumors, and making vaccines available in hard-to-reach places [ 29 ]. Programs like mobile clinics can be replicated if government agencies are familiar with social franchising, subcontracting, and branching out to develop the necessary infrastructure [ 30 ]. Such healthcare-oriented interventions can help achieve a higher percentage of vaccination in the general population. Another strategy that can be employed if necessary in resource-constrained areas is to obtain support through public-private partnerships (PPP), not just for the COVID-19 vaccination program but also for other public healthcare initiatives [ 31 ].

- Sustainability

The main objective of mobile clinics is to create sustainability for long-term impact. Sustainable funding for vaccines and vaccination programs comprises distribution costs, administrative expenses, surveillance, record keeping, and other needs [ 1 ]. Government agencies, the World Bank, and other multilateral banks have allocated extensive resources to achieve vaccination targets worldwide [ 32 ]. However, such financial support for the mobile clinic model should also have an element of internal rate of return and a sustainable cash flow [ 33 ]. Participation of government, private companies, and non-profit organizations has inculcated trust among the general population regarding the vaccine’s efficacy, safety, and affordability. This aspect of social sustainability is achieved through tailor-made strategies to reassure the local population regarding vaccine safety [ 34 ]. Technological assistance is one way to generate engineering sustainability to facilitate a mechanism to control pollution, recycle and reduce waste. A robust data system to check vaccine storage infrastructure, immunization schedules, and other logistics-related matters has enhanced the accountability of mobile clinics and established them as effective vaccination instruments [ 35 ]. Maximum transparency and communication between stakeholders are indispensable for a successful immunization program. Seamless coordination between these parties can aid in project management sustainability, not just at the local level but also at the national level; vaccine roll-out can be tracked, monitored, and evaluated, which helps in formulating efficient campaigns for creating awareness regarding vaccination importance [ 36 ]. Additionally, a robust data infrastructure cannot exist without isolated resources and environmental sustainability. Such data is necessary to identify the individuals eligible for priority vaccinations, create awareness, arrange transportation, and ensure that beneficiaries get the second dose [ 37 ]. The innovative methods adopted helped to coordinate the central pool of vaccine distribution with the local vaccination locations. Such a network ensured the efficient distribution of vaccines with limited wastage after they were removed from cold storage [ 38 ].

Theoretical framework and development of hypotheses

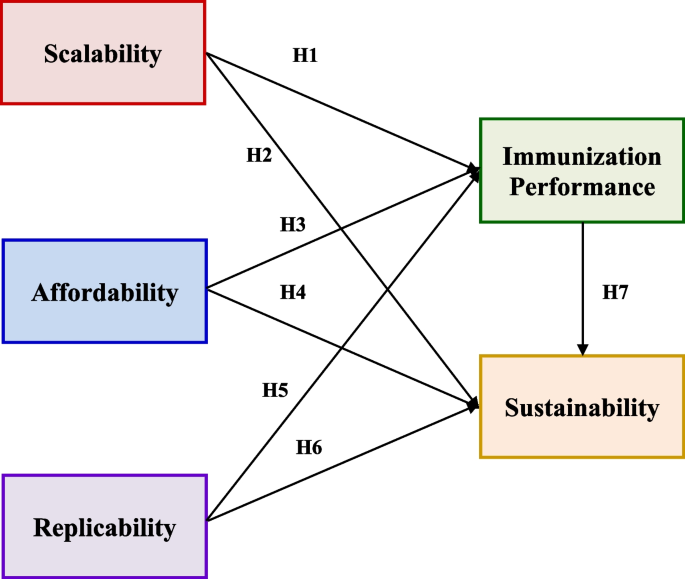

The following hypotheses have been developed based on the theoretical background described in the previous sub-sections to develop a theoretical foundation for this study. The research hypotheses were designed to demonstrate the relationship between the various constructs used in this study. Figure 1 illustrates the structural model for validating the three research hypotheses designed to evaluate the direct relationship between scalability, affordability, and replicability with immunization performance and sustainability.

H 1 . Scalability positively influences immunization performance.

H 2 . Scalability positively influences sustainability.

H 3 . Affordability positively influences immunization performance.

H 4 . Affordability positively influences sustainability.

H 5 . Replicability positively influences immunization performance.

H 6 . Replicability positively influences sustainability.

Conceptual model for empirical testing

Case organization

In the context of mobile clinics in India, the study has considered Jivika Healthcare’s VaccineOnWheels (VOW) as the primary case organization. To develop an operational framework for MMUs by defining the components and analyzing their impacts on immunization performance as the primary healthcare outcome [ 39 ] and sustainability, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Jivika Healthcare Ltd, and the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi partnered to conduct this research. In this regard, Jivika Healthcare's service innovation VaccineOnWheels (VOW) has been regarded as one of several businesses providing immunization services through mobile clinics. In 2019, Jivika Healthcare Private Limited, in partnership with the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, launched Vaccine on Wheels, India's doctor-based mobile vaccination clinic with the objective of “ensuring access to quality vaccination for all” through the following three goals:

to reduce "inequitable access" to vaccines and increase immunization reach

to reduce the vaccine cost by cutting down out-of-pocket expenses, including travel and missed wages

to create awareness of the critical importance of immunization

Jivika's mobile vaccination unit provide ‘doorstep’ service to underserved communities hard-to-reach areas with access to COVID-19 vaccines and up-to-date information regarding vaccine safety and efficacy. To “meet communities where they are,” mobile vaccine units and staff conduct vaccination awareness camps among the community to mitigate the impact of misinformation regarding vaccination effects. In 2019, mobile clinics began mobile vaccination service in Maharashtra’s Pune city. In recent times, the mobile clinic service has been spread across six states of India. Under public-private partnership (PPP), with the support of governments, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and non-profit government organizations (NGOs), the core idea of a mobile clinic “reaching the unreached” grew rapidly. VOW provides sufficient grounds to understand the operational model of a mobile clinic to create a transformative force to increase immunization based upon collaboration with various stakeholders, processes adopted, and strategies implemented during the immunization drive.

This program helped to understand the gaps in the vaccine delivery model from close quarters and identify various issues faced by diverse stakeholders, primarily infants/caregivers/parents, in getting vaccinated. VOW has made vaccines accessible to the elderly, individuals with disabilities, female sex workers, tribal communities, rural communities, street vendors, maids, slum residents, frontline workers, the bedridden, and school children, among other vulnerable segments of society. They have also provided at-home service for those who could not get to the vaccination center, especially persons with disabilities. They have served the people residing in remote locations of the six states through more than 200 mobile vaccination units. Under the unique framework of the PPP, vaccination was administered at a reduced cost for beneficiaries with vaccines provided by the government. The PPP model enables stakeholder collaboration across industries under CSR, government, and NGOs to share a commitment to making vaccination services available even at the grass-roots level. This initiative should help India achieve higher immunization penetration by getting faster acceptance of vaccination, providing convenience, and reducing the cost of service with zero travel cost, travel time, and lost wages.

Research instrument

The questionnaire was developed with the literature review on the factors identified and the significant input from a diverse team of healthcare professionals, including public health experts and academic researchers who have extensive experience in the field of healthcare delivery and MMUs. Their practical insights and hands-on experience were invaluable in formulating relevant and context-specific questions. Given the unique operational environment of MMUs and the specific healthcare needs of rural, tribal, and underprivileged populations in India, we deemed it crucial to tailor the questionnaire to these specific contexts. The expertise of the involved professionals ensured that the questions were both relevant and comprehensive, covering critical aspects of scalability, affordability, replicability, and sustainability.

Questionnaire development began with the identification of the factors to be measured, followed by the selection of items to assess those factors, and then the testing and refinement of the items. The questionnaire items include five significant features derived from the literature linked with mobile clinics: scalability, affordability, replicability, sustainability, and immunization performance. Before distribution to respondents, a team of health professionals and academic researchers evaluated the questionnaire. The questionnaire contained six sub-factors for scalability, three to describe affordability, four to define replicability, and two to define sustainability. To factorize the broad characteristics of mobile clinics, eighteen, nine, twelve, six, and four items were proposed to structure scalability, affordability, replicability, and sustainability, respectively. An example of a statement from the questionnaire describing the scalability of the mobile clinics’ delivery system is “Mobile clinics reply quickly to vaccination-related questions from beneficiaries.”

Respondents to a questionnaire were directed to make appropriate selections ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for each item. A Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) has been utilized to simplify the response to the forty-nine questionnaire items. Various studies have adopted similar empirical techniques for health and policy-related research [ 40 , 41 ].

Statistical analysis

Numerous research studies in health and policy sectors utilize empirical methods including PLS-SEM and Covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) [ 40 , 41 ]. While each method has distinct goals and applications, they can be seen as complementary [ 42 ]. In the realm of public health, PLS-SEM is more apt than CB-SEM for identifying relationships between key influencing factors [ 43 ]. The PLS-SEM technique has become increasingly popular across various disciplines due to its ability to calculate path coefficients, handle latent variables in non-normal distributions, and process data with modest sample sizes [ 44 , 45 ]. The research model in this study was examined using the Partial Least Square Structured Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method [ 46 ]. This study employed Smart PLS 4.0, a renowned tool for PLS-SEM evaluations. The PLS method, using the Smart-PLS 4.0 software, explored the causal connections among constructs. Given the study's explorative nature, the PLS approach has been adopted. Following the recommendations of Henseler et al. (2009), a two-phase data analysis method was adopted [ 47 ]. Initially, the measurement model was evaluated, followed by an exploration of the latent constructs' interrelationships. This two-phase approach ensures the reliability and validity of measurements before delving into the model's structural dynamics [ 48 ].

Sampling technique

According to the standard method for determining sample size in PLS-SEM studies, the model structure should have at least 10 times the number of structural routes [ 49 , 50 ]. There's a notable relationship between sample size and statistical power. For a model with five external variables, a minimum of 169 respondents is recommended to achieve 80% statistical power at a 5% significance level [ 51 , 52 ]. The study ensured to meet the mentioned criteria.

Participants and procedures

The questionnaire assessed mobile clinics' scalability, affordability, replicability, immunization performance, and sustainability. The target respondents for this study were healthcare stakeholders, including health officers, grassroots workers, mobile clinic operators, NGOs, policymakers, and other support staff.

Initially, the questionnaire was tested in a pilot study with a small group of healthcare stakeholders before it was finalized. Feedback from the pilot study was used to make any necessary revisions to the questionnaire. Then, the data was acquired from 207 respondents from the states of Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, Karnataka, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu, directly involved in a mobile clinic vaccination campaign. The respondents occupied a variety of roles within the healthcare system. The states were chosen to collect data since VOW only operated in these states.

The survey was conducted using a self-administered paper-based survey, which lasted for around two months. Participants received the questionnaire in English language and were provided with the detailed explanation of the survey's purpose and instructions on how to complete it. The participants were selected based on their professional roles and expertise in the healthcare sector, specifically those with experience in MMUs or similar healthcare delivery models. This selection criterion ensured that respondents had the necessary knowledge and expertise to answer the questions accurately.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to structure the critical factors of mobile clinics for optimal immunization performance and sustainability. This study employed a survey-based methodology to conduct proper statistical analyses to determine and validate the success factors of mobile clinics.

Respondents’ profiles

The respondents included mobile clinic healthcare workers, support employees, and consulting partners associated with mobile clinics (VOW). To better understand the nature of respondents, we classified them into different demographic profiles to interpret their contribution in terms of gender distribution, states, and geography (Refer Table 1 ). The number of female respondents was only marginally higher than that of male ones, with the female percentage at 51.21% and the male percentage at 48.79%. This shows a great degree of gender equitability in India’s fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, a remarkable sign of equality. Telangana had the highest number of responses (47.34%), followed by Maharashtra (29.5%), showing a non-uniform trend, with the other states being much lower. Thus, the state-wise distribution was governed by the severity of the pandemic showing drastic differences in percentage.

EFA Results

EFA was used as a first stage in the factorization process to extract a factor structure that ensures conceptual significance to the overall study. The initial sample of 100 responses was considered for exercising the EFA. The factor accounting for the most significant common variance was deleted during factor extraction. The Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin (KMO) test was used to ensure data sufficiency for the EFA. The KMO value from the analysis was 0.837, which is considered meritorious by various studies. EFA was carried out using principal component analysis as the extraction method and Varimax rotation as the rotation method. During the EFA procedure, the cross-loading items were deleted iteratively to increase the reliability parameters and obtain a perfect set of factors. Twelve items were deleted throughout this iterative procedure, yielding five factors with eigenvalues greater than one. Table 2 shows the extracted factors and associated items from EFA.

CFA Results

The analysis was carried out to evaluate the derived measurement model using IBM SPSS AMOS 26 [ 53 ]. To begin, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) were used to evaluate internal consistency reliability. The values of α for all obtained factors were more significant than 0.8, while those linked with CR were greater than 0.8. Both α and CR values indicate commendable fit, which implies that they are more significant than the acceptable threshold of 0.7 for all factors [ 52 ], which means that the internal consistency reliability is satisfactory. The outer loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were examined to assess convergent validity. The outside loading values were ≥ 0.7, whereas the AVEs values were more significant than 0.5. [ 54 ]. Thus, convergent validity of the factors was ensured by these findings. Table 3 displays the extracted values for the three outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and average variance.

It was observed that the CFA measurement model fitted the data effectively. Comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated to be 0.96, 0.0503, and 0.035, respectively. Detailed information is provided in Table 4 .

In addition, discriminant validity was evaluated using the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT), as shown in Table 5 . Based on these findings, it is apparent that the discriminant validity of the components in the proposed model was significantly validated by the HTMT standards [ 54 ].

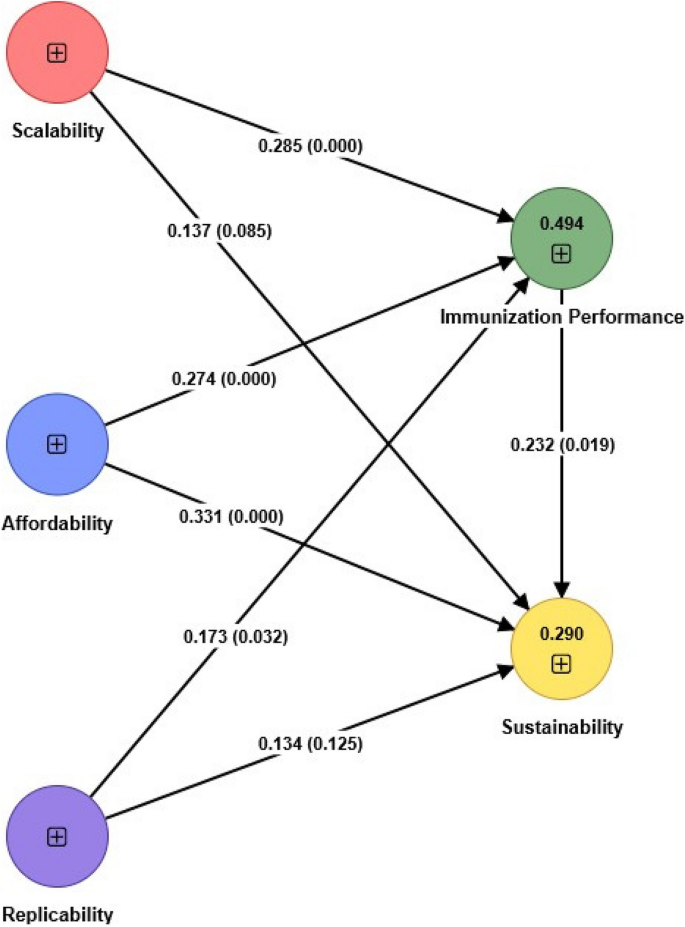

Path model assessment

The model developed in the paper illustrates six critical hypotheses regarding the influence of scalability, affordability, and replicability on immunization performance and sustainability. Moreover, the model demonstrates the hypothesized link between immunization performance and sustainability. For the empirical validation of the model, the gathered data were utilized to examine the hypothesized correlations. Using SmartPLS 4.0 software, the model was empirically validated (Refer Fig. 2 ). Table 6 displays the results obtained by analyzing the structural model. All factors (SAR) were discovered to impact immunization performance substantially. While examining the direct effect of independent factors (SAR) on sustainability, it was observed that only affordability positively affected sustainability. It was also noticeable from the tested model that there was a significant path from immunization performance to sustainability. It is evident from Table 6 that the model has been validated and that several significant hypotheses were supported. The model also revealed an SRMR value of 0.053, indicating a satisfactory model fit. Analysis reveals that the R-squared values for immunization performance and sustainability were 0.494 and 0.290, respectively.

Empirical validation of the model

In general, all significant relationships have values ranging from 0.17 to 0.33. Regarding the effect of independent factors on immunization performance, all three factors (SAR) have a substantial direct effect. Scalability and replicability were found to have a more substantial influence on immunization performance than affordability. The effect (β) values presented for hypotheses H 1 and H 5 are 0.28 and 0.33, respectively.

The β value of affordability on immunization performance (H 3 ) was 0.274. Comparing all three hypothesized links revealed that replicability had the most significant impact, followed by scalability and affordability. Similarly, when investigating the direct relationship between independent factors (SAR) and the sustainability of mobile clinics, the reported β value for the only significant influence of affordability was 0.173. In addition, the hypothesized pathway between immunization performance and sustainability was observed, providing evidence for the association. The reported β value for the relationship between immunization performance and mobile clinics’ sustainability was 0.232. Table 6 provides information regarding the validation of hypothesized linkages.

Equitable access to healthcare and immunizations is crucial for promoting public health, particularly in underserved rural and tribal areas. Mobile Medical Units (MMUs) represent a valuable community-based service delivery approach to address healthcare disparities in both urban and rural settings. While MMUs have been recognized as essential providers of medical care, their full potential and effectiveness have not been comprehensively explored in previous studies. This empirical study was conducted to shed light on the critical factors influencing the effectiveness and sustainability of mobile clinics for immunization programs.

The primary objective of this study was to discern the critical components of the operational model for MMUs and assess their impact on immunization performance and the sustainability of the model within the context of primary healthcare. For this purpose, a quantitative analysis assessed the five key factors: scalability, affordability, replicability, immunization performance, and sustainability. By employing structural equation modeling, the direct effects of these factors were examined. We aimed to construct a framework of guidelines that could enhance healthcare coverage in developing countries, specifically focusing on developing countries like India. The findings directly address the research objectives by elucidating the relationships among scalability, affordability, replicability, immunization performance, and sustainability of the MMUs operational model. In support of RO1, the results showcased that scalability, affordability, and replicability (SAR) significantly influence immunization performance, with replicability having the most substantial impact. Furthermore, immunization performance has a direct effect on the sustainability of MMUs, underscoring its crucial role. These findings collectively inform the development of a comprehensive framework for MMUs, as outlined in RO2. This framework emphasizes that to achieve sustainable primary healthcare innovations, MMUs must prioritize enhancing immunization performance through scalable, affordable, and replicable models. By directly linking these empirical findings to our research objectives, we provide actionable insights for policymakers and healthcare professionals.

Our empirical findings have yielded valuable insights into the factors contributing to mobile clinics' successful operation in India. Scalability primarily hinges on a well-defined delivery system, technical support, organizational capability, partnerships, integration, and community engagement. Affordability is closely linked to factors such as the procurement and distribution of vaccines, cold storage infrastructure, waste management, and managing both direct and indirect costs. Replicability, however, depends on open-sourcing training, strategic collaboration, and capacity building.

In the sustainability domain, a significant emphasis was placed on developing an ecosystem that supports the enduring presence of mobile clinics. This involves effective management strategies that ensure both social and project sustainability. This includes securing funding for vaccines, equipment, maintenance, and staff salaries, establishing strategic partnerships with local stakeholders, raising public awareness about immunization programs, and ensuring equitable access to quality immunization services for all, regardless of socioeconomic status or geographical location.

During the factorization process, it became evident that the delivery system is pivotal in determining scalability. Successful mobile clinics must implement standard operating procedures, maintain effective communication and data management systems, and possess a well-trained workforce capable of allocating resources efficiently to meet the diverse needs of their communities.

Similarly, in terms of affordability, cold storage and waste management emerged as the key factors. Ensuring that vaccines are stored at the appropriate temperature during transportation, particularly in remote areas, is essential for cost-effectiveness and minimizing dose wastage in immunization programs.

In the context of replicability, capacity building was identified as the strongest indicator. Building the competence of mobile clinic teams, which include nurse practitioners, physicians, public health workers, and other healthcare professionals, is critical for agile and effective vaccine delivery. Proper training and adherence to best practices are essential for success.

Lastly, when examining the 'sustainability' factor, it became evident that creating an ecosystem conducive to the long-term operation of mobile clinics is vital. This involves continuous monitoring, sound financial planning, strategic partnerships, public awareness campaigns, and a commitment to equitable service provision.

Considering the overall model, the validated framework highlights the significance of scalability, affordability, and replicability in improving immunization performance. However, while affordability significantly impacts sustainability, the other factors appear to have no direct influence. Nevertheless, a strong link exists between immunization performance and the sustainability of mobile clinics. Affordable mobile clinics are more likely to be utilized, resulting in improved immunization rates and greater sustainability due to increased demand. Furthermore, the scalability and replicability of mobile clinics enables them to adapt to various contexts, which encourages broader adoption and, consequently, enhances their long-term sustainability. This study underscores the vitality of these factors in optimizing the impact of mobile clinics in advancing public health goals.

Previous studies have highlighted the challenges and benefits of scaling up healthcare interventions and replicating successful models in different settings. Our study builds on this body of work by empirically demonstrating that while scalability and replicability do not have a direct effect on sustainability, they significantly influence immunization performance, which in turn impacts sustainability. This finding adds a nuanced understanding of the indirect pathways through which these factors contribute to sustainable healthcare systems.

Affordability has consistently been recognized as a critical factor in healthcare delivery, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Our results corroborate this by showing that affordability significantly impacts immunization performance, thus reinforcing the need for cost-effective healthcare solutions. This aligns with existing literature that emphasizes the importance of economic feasibility in healthcare interventions.

This study confirms the pivotal role of immunization performance in achieving sustainability, consistent with prior research that underscores the importance of effective immunization programs for long-term health outcomes. By linking immunization performance directly to sustainability, our findings provide empirical support for strategies aimed at enhancing immunization coverage as a pathway to sustainable healthcare.

The healthcare challenges addressed in this study, such as equitable access to healthcare for rural, tribal, and underprivileged populations, are not unique to India. Many developing countries face similar issues, making the findings of this study potentially applicable to other contexts. The operational model of MMUs evaluated in this study can serve as a reference for other developing countries looking to implement or enhance similar healthcare interventions.

The concept of scalability, as evaluated in this study, involves expanding healthcare interventions while maintaining effectiveness and efficiency. This aspect is crucial for developing countries with large rural populations and limited healthcare infrastructure. Affordability is a significant consideration in many developing countries where economic constraints limit access to healthcare services. The insights from this study on making MMUs cost-effective can guide policymakers in similar settings. The ability to replicate successful healthcare interventions in different settings is vital for broader implementation. The findings of this study on the replicability of MMUs can inform strategies in other developing countries to achieve consistent healthcare outcomes. Ensuring the long-term sustainability of healthcare interventions is a common challenge across developing nations. The study's findings on the sustainability of MMUs provide a framework for integrating such models into existing health systems for lasting impact.

Research on improving the sustainability of MMUs has not received much attention in developing countries and has also been recognized as a prominent gap in the past literature [ 10 ]. This study recognized that MMUs have the capability to engage and win underprivileged people’s trust by driving directly into communities and opening their doors on the steps of their target beneficiaries. Services offered by MMUs have been proven to enhance immunization coverage and individual health outcomes, advance community health, and lower healthcare costs compared with typical clinical settings because MMUs can overcome numerous healthcare barriers. MMUs can operate as significant players in our developing healthcare system since they can address social, behavioral, and medical health challenges and act as a bridge between the physical clinics and the community. Continuous research must be conducted to resolve the problems and enhance the capacity of MMUs, strengthen the cost-effectiveness of MMUs services, and explore both qualitative and quantitative evidence to advocate for more widespread integration of MMUs into the public health ecosystem to tackle some of the most significant challenges facing primary healthcare services in the current day.

The study examined the impact of scalability, affordability, and replicability on immunization performance and further the effect of immunization performance on the sustainability of the MMUs operation model in the future. While the initiative applies to all regions, it benefited Tier-II, rural, and tribal communities. The mobile vaccination program aims to reach and vaccinate people in hard-to-reach locations. In this way, the program had firmly established itself in urban catchment areas, rural and tribal communities. Finally, a similar model is believed to be replicated in other distant and underprivileged regions of India where healthcare services are lacking. For future routine immunization programs and other primary healthcare services in rural and tribal areas, a similar strategy can be implemented.

Additionally, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The operational model of MMUs might vary significantly across different regions and settings. The study’s findings on scalability, affordability, and replicability may therefore need contextual adaptation when applied to different healthcare environments. Also, the data were collected from healthcare professionals in six states of India, which may not fully represent the diversity of healthcare settings across the entire country. Consequently, the findings may not be entirely generalizable to other regions within India or to other countries with different healthcare contexts.

Implications and future research avenues

MMUs have been recognized as a transformative intervention towards equitable access to health care and the achievement of universal health coverage in developing countries like India. MMUs can be efficient alternatives for delivering quality healthcare to the most vulnerable populations and improving the early diagnosis of various diseases. Practically, this study equips policymakers and public health professionals with the critical components of the MMUs operational model leading toward sustainability. The research framework provides reliable grounds for examining the impact of scalability, affordability, and replicability on immunization coverage as the primary public healthcare outcome. The model can be employed in planning and developing an ecosystem of MMUs for underserved populations and integrating MMUs into the public health structure of a developing country. The model can also be utilized as a management tool for monitoring and assessment of various interventions to be introduced along with MMUs in the future. Practitioners can assess the scalability and affordability of their interventions and improve their decision-making by examining the impact on sustainability.

Our study has primarily identified the impact of scalability, affordability, and replicability on immunization performance, but the model could be extended by examining how the technological readiness of MMUs influences their sustainability. Also, future researchers could explore other public health outcomes and measure the overall impact of scalability, affordability, and replicability on public health in general. In addition, it has been suggested that future researchers utilize a multiple case study approach to examine the impact of the critical components of MMU operation by generating evidence from more than one case organization and covering a wider range of geographies in India.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- Mobile medical units

Scalability, affordability, replicability

Partial least squares structural equation modeling

VaccineOnWheels

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Public-private partnership

Non-profit government organizations

Corporate social responsibility

Covariance based structural equation modeling

Exploratory factor analysis

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

Confirmatory factor analysis

Composite reliability

Average variance extracted

Comparative fit index

Standardized root mean square residual

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio

Root mean square error of approximation

Effect value

Amimo F, Lambert B, Magit A, Hashizume M. A review of prospective pathways and impacts of COVID-19 on the accessibility, safety, quality, and affordability of essential medicines and vaccines for universal health coverage in Africa. Globalization health. 2021;17(1):1–5.

Article Google Scholar

Ho CJ, Khalid H, Skead K, Wong J. The politics of universal health coverage. Lancet. 2022.

Dar M, Moyer W, Dunbar-Hester A, Gunn R, Afokpa V, Federoff N, Brown M, Dave J. Supporting the most vulnerable: Covid-19 vaccination targeting and logistical challenges for the homebound population. NEJM Catalyst Innovations Care Delivery. 2021;2(5). https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0117 .

Kumar A, Nayar KR, Koya SF. COVID-19: Challenges and its consequences for rural health care in India. Public Health Pract. 2020;1:100009.

Das P, Shukla S, Bhagwat A, Purohit S, Dhir S, Jandu HS, Kukreja M, Kothari N, Sharma S, Das S, Taneja G. Modeling a COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. Global J Flex Syst Manage. 2023;24(1):143–61.

Dhawan V, Aggarwal MK, Dhalaria P, Kharb P, Sharma D, Dinesh KK, Dhir S, Taneja G, Ghosh RS. Examining the Impact of Key Factors on COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in India: A PLS-SEM Approach. Vaccines. 2023;11(4):868.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stamm A, Strupat C, Hornidge AK. Global access to COVID-19 vaccines: Challenges in production, affordability, distribution and utilisation. Discussion Paper; 2021.

Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023–34.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Mishra V, Seyedzenouzi G, Almohtadi A, Chowdhury T, Khashkhusha A, Axiaq A, Wong WY, Harky A. Health inequalities during COVID-19 and their effects on morbidity and mortality. J Healthc Leadersh. 2021:19–26.

Khanna AB, Narula SA. Mobile health units: mobilizing healthcare to reach unreachable. Int J Healthc Manag. 2016;9(1):58–66.

Chanda S, Randhawa S, Bambrah HS, Fernandes T, Dogra V, Hegde S. Bridging the gaps in health service delivery for truck drivers of India through mobile medical units. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2020;24(2):84.

Dwivedi YK, Shareef MA, Simintiras AC, Lal B, Weerakkody V. A generalised adoption model for services: A cross-country comparison of mobile health (m-health). Government Inform Q. 2016;33(1):174–87.

Akhtar MH, Ramkumar J. Primary Health Center: Can it be made mobile for efficient healthcare services for hard to reach population? A state-of-the-art review. Discover Health Syst. 2023;2(1):3.

Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, Balasubramaniam P, Narayan K, Paul VK, Kumar AS, Chatterjee M, Reddy KS. Assuring health coverage for all in India. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2422–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Attipoe-Dorcoo S, Delgado R, Gupta A, Bennet J, Oriol NE, Jain SH. Mobile health clinic model in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and opportunities for policy changes and innovation. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–5.

Chillimuntha AK, Thakor KR. Disadvantaged rural health–issues and challenges: a review. Natl J Med Res. 2013;3(01):80–2.

Google Scholar

Landis-Lewis Z, Flynn A, Janda A, Shah N. A scalable service to improve health care quality through precision audit and feedback: proposal for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protocols. 2022;11(5):e34990.

Liu A, Sullivan S, Khan M, Sachs S, Singh P. Community health workers in global health: scale and scalability. Mt Sinai J Medicine: J Translational Personalized Med. 2011;78(3):419–35.

Azizatunnisa L, Cintyamena U, Mahendradhata Y, Ahmad RA. Ensuring sustainability of polio immunization in health system transition: lessons from the polio eradication initiative in Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–6.

Cintyamena U, Azizatunnisa L, Ahmad RA, Mahendradhata Y. Scaling up public health interventions: case study of the polio immunization program in Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–2.

English SW, Barrett KM, Freeman WD, Demaerschalk BM. Telemedicine-enabled ambulances and mobile stroke units for prehospital stroke management. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28(6):458–63.

Ganapathy K, Reddy S. Technology enabled remote healthcare in public private partnership mode: A story from India. Telemedicine, Telehealth and Telepresence: Principles, Strategies, Applications, and New Directions. 2021:197–233.

Lin SC, Zhen A, Zamora-Gonzalez A, Hernández J, Fiala S, Duldulao A. Research Brief Report: Variation in State COVID-19 Disease Reporting Forms on Social Identity, Social Needs, and Vaccination Status. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2022;28(5):486.

Pegurri E, Fox-Rushby JA, Damian W. The effects and costs of expanding the coverage of immunisation services in developing countries: a systematic literature review. Vaccine. 2005;23(13):1624–35.

Levine DM, Chalasani R, Linder JA, Landon BE. Association of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act with ambulatory quality, patient experience, utilization, and cost, 2014–2016. JAMA Netw open. 2022;5(6):e2218167.

Sharma P, Pardeshi G. Rollout of COVID-19 vaccination in India: a SWOT analysis. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2022;16(6):2310–3.

Epstein S, Ayers K, Swenor BK. COVID-19 vaccine prioritisation for people with disabilities. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(6):e361.

Merritt L, Fennie K, Booher J, Fulcher O, Carretta J. Community-led effort to Reduce Disparities in COVID Vaccination: A Replicable Model. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;114(3):S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2021.08.014 .

Chadambuka A, Chimusoro A, Apollo T, Tshimanga M, Namusisi O, Luman ET. The need for innovative strategies to improve immunisation services in rural Zimbabwe. Disasters. 2012;36(1):161–73.

Kumar VM, Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Thyagarajan SP. Strategy for COVID-19 vaccination in India: the country with the second highest population and number of cases. npj Vaccines. 2021;6(1):60.

Baig MB, Panda B, Das JK, Chauhan AS. Is public private partnership an effective alternative to government in the provision of primary health care? A case study in Odisha. J Health Manage. 2014;16(1):41–52.

Skolnik A, Bhatti A, Larson A, Mitrovich R. Silent consequences of COVID-19: why it’s critical to recover routine vaccination rates through equitable vaccine policies and practices. Annals Family Med. 2021;19(6):527–31.

Oriol NE, Cote PJ, Vavasis AP, Bennet J, DeLorenzo D, Blanc P, Kohane I. Calculating the return on investment of mobile healthcare. BMC Med. 2009;7(1):1–6.

Mukherjee S, Baral MM, Chittipaka V, Pal SK, Nagariya R. Investigating sustainable development for the COVID-19 vaccine supply chain: a structural equation modelling approach. J Humanitarian Logistics Supply Chain Manage. 2022.

Christie A, Brooks JT, Hicks LA, Sauber-Schatz EK, Yoder JS, Honein MA, Team COVIDC. Guidance for implementing COVID-19 prevention strategies in the context of varying community transmission levels and vaccination coverage. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(30):1044.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pilati F, Tronconi R, Nollo G, Heragu SS, Zerzer F. Digital twin of COVID-19 mass vaccination centers. Sustainability. 2021;13(13):7396.

Russo AG, Decarli A, Valsecchi MG. Strategy to identify priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination: A population based cohort study. Vaccine. 2021;39(18):2517–25.

Kimble C, Coustasse A, Maxik K. Considerations on the distribution and administration of the new COVID-19 vaccines. Int J Healthc Manag. 2021;14(1):306–10.

Kress DH, Su Y, Wang H. Assessment of primary health care system performance in Nigeria: using the primary health care performance indicator conceptual framework. Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(4):302–18.

Park K, Park J, Kwon YD, Kang Y, Noh JW. Public satisfaction with the healthcare system performance in South Korea: Universal healthcare system. Health Policy. 2016;120(6):621–9.

Hald AN, Bech M, Burau V. Conditions for successful interprofessional collaboration in integrated care–lessons from a primary care setting in Denmark. Health Policy. 2021;125(4):474–81.

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plann. 2013;46(1–2):1–2.

Ali F, Omar R. Determinants of customer experience and resulting satisfaction and revisit intentions: PLS-SEM approach towards Malaysian resort hotels. Asia-Pacific J Innov Hospitality Tourism (APJIHT). 2014;3:1–9.

Henseler J, Dijkstra TK, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Diamantopoulos A, Straub DW, Ketchen DJ Jr, Hair JF, Hult GT, Calantone RJ. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organizational Research Methods. 2014;17(2):182–209.

Rigdon EE. Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: breaking chains and forging ahead. Long Range Plann. 2014;47(3):161–7.

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J Mark theory Pract. 2011;19(2):139–52.

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. InNew challenges to international marketing 2009 Mar 6 (Vol. 20, pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

HUYUT M, Soygüder S. The multi-relationship structure between some symptoms and features seen during the new coronavirus 19 infection and the levels of anxiety and depression post-Covid. Eastern J Med. 2022;27(1):1–10.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Experimental designs using ANOVA. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole; 2007. Dec 6.

Iantovics LB, Rotar C, Morar F. Survey on establishing the optimal number of factors in exploratory factor analysis applied to data mining. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Min Knowl Discovery. 2019;9(2):e1294.

Jung S. Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes: A comparison of three approaches. Behav Process. 2013;97:90–5.

Hair J Jr, Hair JF Jr, Hult GT, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage; 2021.

Book Google Scholar

Hulland J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg Manag J. 1999;20(2):195–204.

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015;43:115–35.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

This study has been funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (027027; RP04054F)

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Jivika Healthcare Private Limited, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Jignesh Patel, Sangita More, Pravin Sohani & Shrinath Bedarkar

Jindal Global Business School, O. P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India

Kamala Kannan Dinesh

Department of Management Studies, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, Delhi, India

Deepika Sharma, Sanjay Dhir & Sushil Sushil

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, New Delhi, India

Gunjan Taneja

Public Health Consultant, New Delhi, India

Raj Shankar Ghosh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JP, SM, PS, SB, SD, SS, GT, and RG conceptualized the paper. KD, DS, SD, and SS collected and analyzed the data. KD and DS prepared the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised and edited by all other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Deepika Sharma .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: annexure 1. profile of respondents based on their expertise., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Patel, J., More, S., Sohani, P. et al. Sustaining the mobile medical units to bring equity in healthcare: a PLS-SEM approach. Int J Equity Health 23 , 175 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02260-x

Download citation

Received : 29 April 2023

Accepted : 26 August 2024

Published : 02 September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02260-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health care

- Immunization

International Journal for Equity in Health

ISSN: 1475-9276

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Oxford Thesis Collection

- CC0 version of this metadata

Integrated care in practice: a case study of health and social care for adults considered to be at high risk of hospital admission

Integrated care is pursued globally as a strategy to manage health and social care resources more effectively. It offers the promise of meeting increasingly complex needs, particularly those of aging populations, in a person-centred, co-ordinated way that addresses fragmentation and improves quality.

However, policy to integrate health and social care in England has led to programmes which have had disappointing effects on reducing hospital admissions and costs. My concern with the...

Email this record

Please enter the email address that the record information will be sent to.

Please add any additional information to be included within the email.

Cite this record

Chicago style, access document.

- HUGHES 2018 thesis.pdf ( Preview , pdf, 3.1MB, Terms of use )

Why is the content I wish to access not available via ORA?

Content may be unavailable for the following four reasons.

- Version unsuitable We have not obtained a suitable full-text for a given research output. See the versions advice for more information.

- Recently completed Sometimes content is held in ORA but is unavailable for a fixed period of time to comply with the policies and wishes of rights holders.

- Permissions All content made available in ORA should comply with relevant rights, such as copyright. See the copyright guide for more information.

- Clearance Some thesis volumes scanned as part of the digitisation scheme funded by Dr Leonard Polonsky are currently unavailable due to sensitive material or uncleared third-party copyright content. We are attempting to contact authors whose theses are affected.

Alternative access to the full-text

Request a copy.

We require your email address in order to let you know the outcome of your request.

Provide a statement outlining the basis of your request for the information of the author.

Please note any files released to you as part of your request are subject to the terms and conditions of use for the Oxford University Research Archive unless explicitly stated otherwise by the author.

Contributors

Bibliographic details, item description, terms of use, views and downloads.

If you are the owner of this record, you can report an update to it here: Report update to this record

Report an update

We require your email address in order to let you know the outcome of your enquiry.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Updates For the latest information and advice see: Coronavirus (COVID-19) frequently asked questions

Scottish Graduate School of Social Science

Improving person-centred care communication in health and social care settings.

PHD STUDENT: Natalia Rodriguez UNIVERSITY: Heriot-Watt COMPANY: Healthcare Improvement Scotland

In January 2019 Healthcare Improvement Scotland welcomed Natalia Rodriguez to undertake a 3 month internship. Natalia is studying for a PhD with a focus on interpreting in mental healthcare settings at Heriot Watt University. During her time at Healthcare Improvement Scotland she worked within the Evidence and Evaluation for Improvement Team (EEvIT), supporting them to evaluate the ‘What Matters to You? Day’ (WMTY) initiative that is facilitated by the Person Centred Care Team. Natalia was happy to share information about her experience below.

"It has been an absolute joy working with Natalia. She has been a breath of fresh air. She picked it up quickly and I didn't feel that I had to direct her too much. I think we really lucked out on Natalia's skill set." Colleague from HIS

What attracted you to this internship?

When I first saw the advertisement for an internship position for PhD candidates with Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS) I was both thrilled and hesitant about applying. On paper, I was a good candidate, but I wondered if my academic background would be the right fit for the organisation. On the other hand, I was sure that it would be a great opportunity for me and that I definitely wanted to put my research skills to use in public healthcare.

My PhD had already given me the chance to witness the work of the NHS first-hand. For data collection purposes, I observed consultations conducted through spoken-language interpreters in two psychiatric wards within NHS Lothian for over a year. During this time, I not only collected data but also learnt lessons about human resilience that I will always carry with me. Having finished the data-collection work in December, I have now a year of funding left to convert my data into a thesis. So, the chance to work with HIS in this transition stage could not have come at a better time!

What did you do?

During my time at HIS, I supported the Evidence and Evaluation for Improvement Team (EEvIT). Specifically, I supported EEvIT to evaluate the ‘What matters to you? day’ initiative that is facilitated by the Person-Centred Care Team within HIS. For this purpose, I conducted primary and secondary research to produce an evidence report called: “‘What matters to you?’ Embedding the question in everyday practice: a multiple case-study”.

Did the internship meet your expectations?

It definitely exceeded my expectations. When I applied for the post, I was expecting that I would be doing some kind of work for a public health organisation, which in itself was to enough to make me feel excited. What I did not know then was that I would be applying my whole range of research skills to explore a topic fully in line with my PhD aims. I really was not expecting that before I started.

How did you utilise your research skills and knowledge during the internship?

There was clear common ground between my PhD topic and the aims of my internship project, which made it possible for me to use my knowledge and apply the research skills required to fulfil my internship aims. My PhD is about how linguistically and culturally diverse patients access healthcare services when they do not share a language with the service provider. During my internship, I evaluated the impact of a campaign that aims to promote a communication model in which patients and practitioners are encouraged to interact as equal partners in the planning of care. Methodologically speaking, for my PhD I have adopted a single case-study research design and for my internship, I adopted a multiple-case study design. In summary, my knowledge on the topic and the methodology required to explore was useful as a starting point, but the internship aims required me to take my expertise a step further.

How has it impacted your professional and personal development?

I am not sure about what type of work I will conduct after my PhD but public health and social care provision is definitely a research and personal interest that I am going to carry with me for life after my internship.

I do believe that my internship will help open up a new range of future possibilities that I would have never even thought about until now. The National Health Service is such a complex organisation that encompasses so many different departments, teams and staff with different backgrounds. Particularly, Healthcare Improvement Scotland contains different portfolios that have different objectives but pursue the common aim of driving improvement in the provision of health and social care services. This is an excellent area of work and definitely worth considering in the future.

Are there any outputs from the internship that you would like to share?

It was key for me to meet other people in the organisation outside from the team that I was allocated to work with as that provided me with unintended benefits. E.g. I was able to meet the Equality and Diversity advisor from HIS whose work is closely connected with my research interests and PhD aims. Because of his support, I was able to provide some feedback on a policy document draft around my area of expertise (healthcare interpreting) that will soon be published. That was not part of my internship aims but I definitely count that as one my main internship accomplishments.

What transferable skills did you learn?

Communicate clearly with a wide audience. During my internship I worked with a multidisciplinary team made up of health service researchers, a health economist and an information scientist. During data-collection, I interviewed people with a wide range of backgrounds including consultant, nurses, health service managers, etc. Developing appropriate timescales and sticking to them which was key to success as I was fully responsible for the development of the project. Being flexible: we had to consider different study designs as we depended on data availability.

How did you find coming back to your research after the internship?

I feel more confident now when approaching my PhD dataset. I did my internship during a transition time, right in between finishing data collection and starting data analysis and subsequent reporting. During my internship, I had to analyse and report data and that gave me a small-scale taster of what would come after. A team of health service researchers supported my work and provided guidance at all times so that I could fulfil my internship study aims. I am going to keep using that guidance to safeguard rigour in my own research work. I feel that I have more research tools and resources now.