- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Eating And Health

- Food For Thought

- For Foodies

Are Junk Food Habits Driving Obesity? A Tale Of Two Studies

Maria Godoy

What role do high-calorie, low-nutrition junk foods play in expanding waistlines? Two recent studies tackle that question. Morgan McCloy/NPR hide caption

What role do high-calorie, low-nutrition junk foods play in expanding waistlines? Two recent studies tackle that question.

More than 36 percent of American adults and 17 percent of youth under 19 are obese, according to the latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scientists still don't fully understand what got us here. And sometimes, the answers they've come up with turn out to be wrong. Consider the changing advice on fat , which has been amended of late from its days as a dietary demon.

By now, it would seem that the link between the obesity epidemic and the consumption of high-calorie, low-nutrition foods like sodas, cookies and fries is well-established. But as two recent studies show, researchers are still probing the mechanics of that connection.

Broadly speaking, both studies explore the connection between junk food and weight — though they do so using different data sets from two different populations (adults and kids).

Let's start with the finding that seems most counterintuitive: For most of us, junk foods may not be what's driving weight gain. That's what behavioral economist David Just and his colleagues at the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab concluded in a paper in the journal Obesity Science & Practice.

The researchers looked at data collected in 2007-2008 from a nationally representative sample of roughly 5,000 U.S. adults as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) , including information on weight, height and eating habits. Junk food was defined as fast food, soda and sweets.

Some of that data set had been used in a 2013 CDC study that found that heavier Americans were indeed getting more of their daily calories from fast food. But the Cornell researchers wondered what would happen if they excluded the people on the extreme ends of the weight spectrum — those who are clinically underweight and the very morbidly obese.

And they found that once those groups were eliminated, there was no association between body mass index and how much fast food, sugary sodas and sweets people consume.

The finding, which applies to 95 percent of the population, "was really counterintuitive — not what we expected at all," Just tells The Salt.

But if fast food isn't driving the obesity epidemic, what is? "I suspect we're eating too many calories from all foods," Just says. He points to data from the USDA's Economic Research Service showing that Americans, on average, now eat 500 calories more daily than they did around 1970, before the obesity epidemic took off.

To be clear, Just isn't saying that you can eat all the junk food you want with no consequence. "You increase your consumption of these things, yeah, you're going to put on weight," he says. "But that's not to say that is the differentiator between those who are overweight and those who aren't." And if that's the case, Just says, instead of targeting junk foods in the war against obesity, maybe we should be preaching the gospel of moderation and portion control with all foods.

Sure, that's good advice in general — but it may not mean we can let junk foods off the hook.

Eric Finkelstein , an associate professor at the Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University, notes that the data the Cornell researchers used is only a snapshot of what a cross-section of Americans were eating at a single moment in time. So it's possible, for example, that the overweight and obese people included in the study reported eating less junk foods because they were trying to lose weight.

"I'd lend a lot more credence to studies that follow change [in eating habits and weight] over time," Finkelstein tells The Salt.

And, over time, he says, the evidence suggests strongly that even modest increases in the consumption of certain foods will result in long-term weight gain. He points to a 2011 study in the New England Journal of Medicine that looked at data gathered over decades on 120,000 U.S. adults. Over a four-year period, an extra daily serving of potato chips was associated with weight gain of 1.69 pounds, the study found. That may not sound like much, but for most adults, that's how the pounds add up — gradually, over time, at an average rate of about a pound a year .

And problem foods will pack on the pounds for kids, too. Last week, Finkelstein and his colleagues published a similarly detailed breakdown of the links between weight gain and certain foods in children. The researchers turned to data on more than 4,600 kids from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children , an ongoing study in the U.K. that has tracked the same set of children — with records on their height, weight and food intake — since their birth in the early 1990s.

Once again, potato chips raised red flags.

As the researchers reported in the journal Health Affairs , over a three-year period, every 25-gram serving of potato chips (a little under an ounce) that kids ate daily was linked to about a half-pound of excess weight gain. (Basically, that's defined as weight beyond what a child should weigh for his or her height and age.)

Again, half a pound doesn't sound alarming, "but if you're also getting an extra half a pound from burgers, and half a pound from french fries, these things add up. And some kids are eating more than a serving" daily, Finkelstein says.

Other foods the study linked to excessive weight gain included "kid food" staples — like breaded and coated fish and poultry (think fish sticks and chicken nuggets) and french fries — and processed meats, butter and margarine, desserts and sweets.

That's important, because some 31 percent of American and 38 percent of European kids are now overweight or obese — and the pounds we gain as kids often stay with us through adulthood.

- childhood obesity

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

The Impacts of Junk Food on Health

Energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, otherwise known as junk foods, have never been more accessible and available. Young people are bombarded with unhealthy junk-food choices daily, and this can lead to life-long dietary habits that are difficult to undo. In this article, we explore the scientific evidence behind both the short-term and long-term impacts of junk food consumption on our health.

Introduction

The world is currently facing an obesity epidemic, which puts people at risk for chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes. Junk food can contribute to obesity and yet it is becoming a part of our everyday lives because of our fast-paced lifestyles. Life can be jam-packed when you are juggling school, sport, and hanging with friends and family! Junk food companies make food convenient, tasty, and affordable, so it has largely replaced preparing and eating healthy homemade meals. Junk foods include foods like burgers, fried chicken, and pizza from fast-food restaurants, as well as packaged foods like chips, biscuits, and ice-cream, sugar-sweetened beverages like soda, fatty meats like bacon, sugary cereals, and frozen ready meals like lasagne. These are typically highly processed foods , meaning several steps were involved in making the food, with a focus on making them tasty and thus easy to overeat. Unfortunately, junk foods provide lots of calories and energy, but little of the vital nutrients our bodies need to grow and be healthy, like proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Australian teenagers aged 14–18 years get more than 40% of their daily energy from these types of foods, which is concerning [ 1 ]. Junk foods are also known as discretionary foods , which means they are “not needed to meet nutrient requirements and do not belong to the five food groups” [ 2 ]. According to the dietary guidelines of Australian and many other countries, these five food groups are grains and cereals, vegetables and legumes, fruits, dairy and dairy alternatives, and meat and meat alternatives.

Young people are often the targets of sneaky advertising tactics by junk food companies, which show our heroes and icons promoting junk foods. In Australia, cricket, one of our favorite sports, is sponsored by a big fast-food brand. Elite athletes like cricket players are not fuelling their bodies with fried chicken, burgers, and fries! A study showed that adolescents aged 12–17 years view over 14.4 million food advertisements in a single year on popular websites, with cakes, cookies, and ice cream being the most frequently advertised products [ 3 ]. Another study examining YouTube videos popular amongst children reported that 38% of all ads involved a food or beverage and 56% of those food ads were for junk foods [ 4 ].

What Happens to Our Bodies Shortly After We Eat Junk Foods?

Food is made up of three major nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. There are also vitamins and minerals in food that support good health, growth, and development. Getting the proper nutrition is very important during our teenage years. However, when we eat junk foods, we are consuming high amounts of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, which are quickly absorbed by the body.

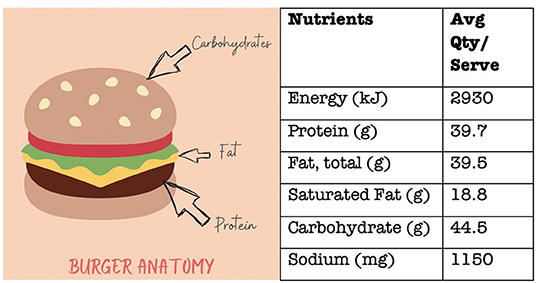

Let us take the example of eating a hamburger. A burger typically contains carbohydrates from the bun, proteins and fats from the beef patty, and fats from the cheese and sauce. On average, a burger from a fast-food chain contains 36–40% of your daily energy needs and this does not account for any chips or drinks consumed with it ( Figure 1 ). This is a large amount of food for the body to digest—not good if you are about to hit the cricket pitch!

- Figure 1 - The nutritional composition of a popular burger from a famous fast-food restaurant, detailing the average quantity per serving and per 100 g.

- The carbohydrates of a burger are mainly from the bun, while the protein comes from the beef patty. Large amounts of fat come from the cheese and sauce. Based on the Australian dietary guidelines, just one burger can be 36% of the recommended daily energy intake for teenage boys aged 12–15 years and 40% of the recommendations for teenage girls 12–15 years.

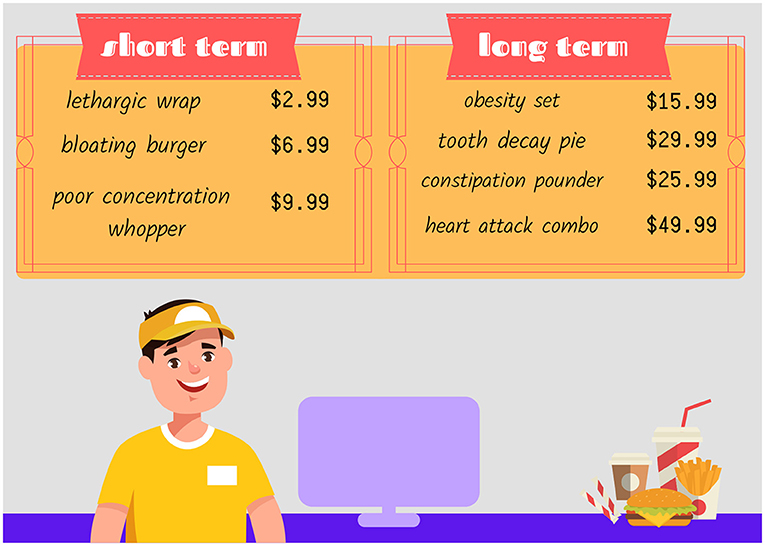

A few hours to a few days after eating rich, heavy foods such as a burger, unpleasant symptoms like tiredness, poor sleep, and even hunger can result ( Figure 2 ). Rather than providing an energy boost, junk foods can lead to a lack of energy. For a short time, sugar (a type of carbohydrate) makes people feel energized, happy, and upbeat as it is used by the body for energy. However, refined sugar , which is the type of sugar commonly found in junk foods, leads to a quick drop in blood sugar levels because it is digested quickly by the body. This can lead tiredness and cravings [ 5 ].

- Figure 2 - The short- and long-term impacts of junk food consumption.

- In the short-term, junk foods can make you feel tired, bloated, and unable to concentrate. Long-term, junk foods can lead to tooth decay and poor bowel habits. Junk foods can also lead to obesity and associated diseases such as heart disease. When junk foods are regularly consumed over long periods of time, the damages and complications to health are increasingly costly.

Fiber is a good carbohydrate commonly found in vegetables, fruits, barley, legumes, nuts, and seeds—foods from the five food groups. Fiber not only keeps the digestive system healthy, but also slows the stomach’s emptying process, keeping us feeling full for longer. Junk foods tend to lack fiber, so when we eat them, we notice decreasing energy and increasing hunger sooner.

Foods such as walnuts, berries, tuna, and green veggies can boost concentration levels. This is particularly important for young minds who are doing lots of schoolwork. These foods are what most elite athletes are eating! On the other hand, eating junk foods can lead to poor concentration. Eating junk foods can lead to swelling in the part of the brain that has a major role in memory. A study performed in humans showed that eating an unhealthy breakfast high in fat and sugar for 4 days in a row caused disruptions to the learning and memory parts of the brain [ 6 ].

Long-Term Impacts of Junk Foods

If we eat mostly junk foods over many weeks, months, or years, there can be several long-term impacts on health ( Figure 2 ). For example, high saturated fat intake is strongly linked with high levels of bad cholesterol in the blood, which can be a sign of heart disease. Respected research studies found that young people who eat only small amounts of saturated fat have lower total cholesterol levels [ 7 ].

Frequent consumption of junk foods can also increase the risk of diseases such as hypertension and stroke. Hypertension is also known as high blood pressure and a stroke is damage to the brain from reduced blood supply, which prevents the brain from receiving the oxygen and nutrients it needs to survive. Hypertension and stroke can occur because of the high amounts of cholesterol and salt in junk foods.

Furthermore, junk foods can trigger the “happy hormone,” dopamine , to be released in the brain, making us feel good when we eat these foods. This can lead us to wanting more junk food to get that same happy feeling again [ 8 ]. Other long-term effects of eating too much junk food include tooth decay and constipation. Soft drinks, for instance, can cause tooth decay due to high amounts of sugar and acid that can wear down the protective tooth enamel. Junk foods are typically low in fiber too, which has negative consequences for gut health in the long term. Fiber forms the bulk of our poop and without it, it can be hard to poop!

Tips for Being Healthy

One way to figure out whether a food is a junk food is to think about how processed it is. When we think of foods in their whole and original forms, like a fresh tomato, a grain of rice, or milk squeezed from a cow, we can then start to imagine how many steps are involved to transform that whole food into something that is ready-to-eat, tasty, convenient, and has a long shelf life.

For teenagers 13–14 years old, the recommended daily energy intake is 8,200–9,900 kJ/day or 1,960 kcal-2,370 kcal/day for boys and 7,400–8,200 kJ/day or 1,770–1,960 kcal for girls, according to the Australian dietary guidelines. Of course, the more physically active you are, the higher your energy needs. Remember that junk foods are okay to eat occasionally, but they should not make up more than 10% of your daily energy intake. In a day, this may be a simple treat such as a small muffin or a few squares of chocolate. On a weekly basis, this might mean no more than two fast-food meals per week. The remaining 90% of food eaten should be from the five food groups.

In conclusion, we know that junk foods are tasty, affordable, and convenient. This makes it hard to limit the amount of junk food we eat. However, if junk foods become a staple of our diets, there can be negative impacts on our health. We should aim for high-fiber foods such as whole grains, vegetables, and fruits; meals that have moderate amounts of sugar and salt; and calcium-rich and iron-rich foods. Healthy foods help to build strong bodies and brains. Limiting junk food intake can happen on an individual level, based on our food choices, or through government policies and health-promotion strategies. We need governments to stop junk food companies from advertising to young people, and we need their help to replace junk food restaurants with more healthy options. Researchers can focus on education and health promotion around healthy food options and can work with young people to develop solutions. If we all work together, we can help young people across the world to make food choices that will improve their short and long-term health.

Obesity : ↑ A disorder where too much body fat increases the risk of health problems.

Processed Food : ↑ A raw agricultural food that has undergone processes to be washed, ground, cleaned and/or cooked further.

Discretionary Food : ↑ Foods and drinks not necessary to provide the nutrients the body needs but that may add variety to a person’s diet (according to the Australian dietary guidelines).

Refined Sugar : ↑ Sugar that has been processed from raw sources such as sugar cane, sugar beets or corn.

Saturated Fat : ↑ A type of fat commonly eaten from animal sources such as beef, chicken and pork, which typically promotes the production of “bad” cholesterol in the body.

Dopamine : ↑ A hormone that is released when the brain is expecting a reward and is associated with activities that generate pleasure, such as eating or shopping.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. 4324.0.55.002 - Microdata: Australian Health Survey: Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2011-12 . Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online at: http://bit.ly/2jkRRZO (accessed December 13, 2019).

[2] ↑ National Health and Medical Research Council. 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines Summary . Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

[3] ↑ Potvin Kent, M., and Pauzé, E. 2018. The frequency and healthfulness of food and beverages advertised on adolescents’ preferred web sites in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health. 63:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.007

[4] ↑ Tan, L., Ng, S. H., Omar, A., and Karupaiah, T. 2018. What’s on YouTube? A case study on food and beverage advertising in videos targeted at children on social media. Child Obes. 14:280–90. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0037

[5] ↑ Gómez-Pinilla, F. 2008. Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 568–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn2421

[6] ↑ Attuquayefio, T., Stevenson, R. J., Oaten, M. J., and Francis, H. M. 2017. A four-day western-style dietary intervention causes reductions in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and interoceptive sensitivity. PLoS ONE . 12:e0172645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172645

[7] ↑ Te Morenga, L., and Montez, J. 2017. Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 12:e0186672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186672

[8] ↑ Reichelt, A. C. 2016. Adolescent maturational transitions in the prefrontal cortex and dopamine signaling as a risk factor for the development of obesity and high fat/high sugar diet induced cognitive deficits. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00189

How Junk Food Can End Obesity

Demonizing processed food may be dooming many to obesity and disease. Could embracing the drive-thru make us all healthier?

Late last year, in a small health-food eatery called Cafe Sprouts in Oberlin, Ohio, I had what may well have been the most wholesome beverage of my life. The friendly server patiently guided me to an apple-blueberry-kale-carrot smoothie-juice combination, which she spent the next several minutes preparing, mostly by shepherding farm-fresh produce into machinery. The result was tasty, but at 300 calories (by my rough calculation) in a 16-ounce cup, it was more than my diet could regularly absorb without consequences, nor was I about to make a habit of $9 shakes, healthy or not.

Inspired by the experience nonetheless, I tried again two months later at L.A.’s Real Food Daily, a popular vegan restaurant near Hollywood. I was initially wary of a low-calorie juice made almost entirely from green vegetables, but the server assured me it was a popular treat. I like to brag that I can eat anything, and I scarf down all sorts of raw vegetables like candy, but I could stomach only about a third of this oddly foamy, bitter concoction. It smelled like lawn clippings and tasted like liquid celery. It goes for $7.95, and I waited 10 minutes for it.

I finally hit the sweet spot just a few weeks later, in Chicago, with a delicious blueberry-pomegranate smoothie that rang in at a relatively modest 220 calories. It cost $3 and took only seconds to make. Best of all, I’ll be able to get this concoction just about anywhere. Thanks, McDonald’s!

If only the McDonald’s smoothie weren’t, unlike the first two, so fattening and unhealthy. Or at least that’s what the most-prominent voices in our food culture today would have you believe.

An enormous amount of media space has been dedicated to promoting the notion that all processed food, and only processed food, is making us sickly and overweight. In this narrative, the food-industrial complex—particularly the fast-food industry—has turned all the powers of food-processing science loose on engineering its offerings to addict us to fat, sugar, and salt, causing or at least heavily contributing to the obesity crisis. The wares of these pimps and pushers, we are told, are to be universally shunned.

Consider The New York Times . Earlier this year, The Times Magazine gave its cover to a long piece based on Michael Moss’s about-to-be-best-selling book, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us . Hitting bookshelves at about the same time was the former Times reporter Melanie Warner’s Pandora’s Lunchbox: How Processed Food Took Over the American Meal , which addresses more or less the same theme. Two years ago The Times Magazine featured the journalist Gary Taubes’s “Is Sugar Toxic?,” a cover story on the evils of refined sugar and high-fructose corn syrup. And most significant of all has been the considerable space the magazine has devoted over the years to Michael Pollan, a journalism professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and his broad indictment of food processing as a source of society’s health problems.

“The food they’re cooking is making people sick,” Pollan has said of big food companies. “It is one of the reasons that we have the obesity and diabetes epidemics that we do … If you’re going to let industries decide how much salt, sugar and fat is in your food, they’re going to put [in] as much as they possibly can … They will push those buttons until we scream or die.” The solution, in his view, is to replace Big Food’s engineered, edible evil—through public education and regulation—with fresh, unprocessed, local, seasonal, real food.

Pollan’s worldview saturates the public conversation on healthy eating. You hear much the same from many scientists, physicians, food activists, nutritionists, celebrity chefs, and pundits. Foodlike substances , the derisive term Pollan uses to describe processed foods, is now a solid part of the elite vernacular. Thousands of restaurants and grocery stores, most notably the Whole Foods chain, have thrived by answering the call to reject industrialized foods in favor of a return to natural, simple, nonindustrialized—let’s call them “wholesome”—foods. The two newest restaurants in my smallish Massachusetts town both prominently tout wholesome ingredients; one of them is called the Farmhouse, and it’s usually packed.

A new generation of business, social, and policy entrepreneurs is rising to further cater to these tastes, and to challenge Big Food. Silicon Valley, where tomorrow’s entrepreneurial and social trends are forged, has spawned a small ecosystem of wholesome-friendly venture-capital firms (Physic Ventures, for example), business accelerators (Local Food Lab), and Web sites (Edible Startups) to fund, nurture, and keep tabs on young companies such as blissmo (a wholesome-food-of-the-month club), Mile High Organics (online wholesome-food shopping), and Wholeshare (group wholesome-food purchasing), all designed to help reacquaint Americans with the simpler eating habits of yesteryear.

In virtually every realm of human existence, we turn to technology to help us solve our problems. But even in Silicon Valley, when it comes to food and obesity, technology—or at least food-processing technology—is widely treated as if it is the problem. The solution, from this viewpoint, necessarily involves turning our back on it.

If the most-influential voices in our food culture today get their way, we will achieve a genuine food revolution. Too bad it would be one tailored to the dubious health fantasies of a small, elite minority. And too bad it would largely exclude the obese masses, who would continue to sicken and die early. Despite the best efforts of a small army of wholesome-food heroes, there is no reasonable scenario under which these foods could become cheap and plentiful enough to serve as the core diet for most of the obese population—even in the unlikely case that your typical junk-food eater would be willing and able to break lifelong habits to embrace kale and yellow beets. And many of the dishes glorified by the wholesome-food movement are, in any case, as caloric and obesogenic as anything served in a Burger King.

Through its growing sway over health-conscious consumers and policy makers, the wholesome-food movement is impeding the progress of the one segment of the food world that is actually positioned to take effective, near-term steps to reverse the obesity trend: the processed-food industry. Popular food producers, fast-food chains among them, are already applying various tricks and technologies to create less caloric and more satiating versions of their junky fare that nonetheless retain much of the appeal of the originals, and could be induced to go much further. In fact, these roundly demonized companies could do far more for the public’s health in five years than the wholesome-food movement is likely to accomplish in the next 50. But will the wholesome-food advocates let them?

I. Michael Pollan Has No Clothes

Let’s go shopping. We can start at Whole Foods Market, a critical link in the wholesome-eating food chain. There are three Whole Foods stores within 15 minutes of my house—we’re big on real food in the suburbs west of Boston. Here at the largest of the three, I can choose from more than 21 types of tofu, 62 bins of organic grains and legumes, and 42 different salad greens.

Much of the food isn’t all that different from what I can get in any other supermarket, but sprinkled throughout are items that scream “wholesome.” One that catches my eye today, sitting prominently on an impulse-buy rack near the checkout counter, is Vegan Cheesy Salad Booster, from Living Intentions, whose package emphasizes the fact that the food is enhanced with spirulina, chlorella, and sea vegetables. The label also proudly lets me know that the contents are raw—no processing!—and that they don’t contain any genetically modified ingredients. What the stuff does contain, though, is more than three times the fat content per ounce as the beef patty in a Big Mac (more than two-thirds of the calories come from fat), and four times the sodium.

After my excursion to Whole Foods, I drive a few minutes to a Trader Joe’s, also known for an emphasis on wholesome foods. Here at the register I’m confronted with a large display of a snack food called “Inner Peas,” consisting of peas that are breaded in cornmeal and rice flour, fried in sunflower oil, and then sprinkled with salt. By weight, the snack has six times as much fat as it does protein, along with loads of carbohydrates. I can’t recall ever seeing anything at any fast-food restaurant that represents as big an obesogenic crime against the vegetable kingdom. (A spokesperson for Trader Joe’s said the company does not consider itself a “ ‘wholesome food’ grocery retailer.” Living Intentions did not respond to a request for comment.)

This phenomenon is by no means limited to packaged food at upscale supermarkets. Back in February, when I was at Real Food Daily in Los Angeles, I ordered the “Sea Cake” along with my green-vegetable smoothie. It was intensely delicious in a way that set off alarm bells. RFD wouldn’t provide precise information about the ingredients, but I found a recipe online for “Tofu ‘Fish’ Cakes,” which seem very close to what I ate. Essentially, they consist of some tofu mixed with a lot of refined carbs (the RFD version contains at least some unrefined carbs) along with oil and soy milk, all fried in oil and served with a soy-and-oil-based tartar sauce. (Tofu and other forms of soy are high in protein, but per 100 calories, tofu is as fatty as many cuts of beef.) L.A. being to the wholesome-food movement what Hawaii is to Spam, I ate at two other mega-popular wholesome-food restaurants while I was in the area. At Café Gratitude I enjoyed the kale chips and herb-cornmeal-crusted eggplant parmesan, and at Akasha I indulged in a spiced-lamb-sausage flatbread pizza. Both are pricey orgies of fat and carbs.

I’m not picking out rare, less healthy examples from these establishments. Check out their menus online: fat, sugar, and other refined carbs abound. (Café Gratitude says it uses only “healthy” fats and natural sweeteners; Akasha says its focus is not on “health food” but on “farm to fork” fare.) In fact, because the products and dishes offered by these types of establishments tend to emphasize the healthy-sounding foods they contain, I find it much harder to navigate through them to foods that go easy on the oil, butter, refined grains, rice, potatoes, and sugar than I do at far less wholesome restaurants. (These dishes also tend to contain plenty of sea salt, which Pollanites hold up as the wholesome alternative to the addictive salt engineered by the food industry, though your body can’t tell the difference.)

One occasional source of obesogenic travesties is The New York Times Magazine ’s lead food writer, Mark Bittman, who now rivals Pollan as a shepherd to the anti-processed-food flock. ( Salon , in an article titled “How to Live What Michael Pollan Preaches,” called Bittman’s 2009 book, Food Matters , “both a cookbook and a manifesto that shows us how to eat better—and save the planet.”) I happened to catch Bittman on the Today show last year demonstrating for millions of viewers four ways to prepare corn in summertime, including a lovely dish of corn sautéed in bacon fat and topped with bacon. Anyone who thinks that such a thing is much healthier than a Whopper just hasn’t been paying attention to obesity science for the past few decades.

That science is, in fact, fairly straightforward. Fat carries more than twice as many calories as carbohydrates and proteins do per gram, which means just a little fat can turn a serving of food into a calorie bomb. Sugar and other refined carbohydrates, like white flour and rice, and high-starch foods, like corn and potatoes, aren’t as calorie-dense. But all of these “problem carbs” charge into the bloodstream as glucose in minutes, providing an energy rush, commonly followed by an energy crash that can lead to a surge in appetite.

Because they are energy-intense foods, fat and sugar and other problem carbs trip the pleasure and reward meters placed in our brains by evolution over the millions of years during which starvation was an ever-present threat. We’re born enjoying the stimulating sensations these ingredients provide, and exposure strengthens the associations, ensuring that we come to crave them and, all too often, eat more of them than we should. Processed food is not an essential part of this story: recent examinations of ancient human remains in Egypt, Peru, and elsewhere have repeatedly revealed hardened arteries, suggesting that pre-industrial diets, at least of the affluent, may not have been the epitome of healthy eating that the Pollanites make them out to be. People who want to lose weight and keep it off are almost always advised by those who run successful long-term weight-loss programs to transition to a diet high in lean protein, complex carbs such as whole grains and legumes, and the sort of fiber vegetables are loaded with. Because these ingredients provide us with the calories we need without the big, fast bursts of energy, they can be satiating without pushing the primitive reward buttons that nudge us to eat too much.

(A few words on salt: Yes, it’s unhealthy in large amounts, raising blood pressure in many people; and yes, it makes food more appealing. But salt is not obesogenic—it has no calories, and doesn’t specifically increase the desire to consume high-calorie foods. It can just as easily be enlisted to add to the appeal of vegetables. Lumping it in with fat and sugar as an addictive junk-food ingredient is a confused proposition. But let’s agree we want to cut down on it.)

To be sure, many of Big Food’s most popular products are loaded with appalling amounts of fat and sugar and other problem carbs (as well as salt), and the plentitude of these ingredients, exacerbated by large portion sizes, has clearly helped foment the obesity crisis. It’s hard to find anyone anywhere who disagrees. Junk food is bad for you because it’s full of fat and problem carbs. But will switching to wholesome foods free us from this scourge? It could in theory, but in practice, it’s hard to see how. Even putting aside for a moment the serious questions about whether wholesome foods could be made accessible to the obese public, and whether the obese would be willing to eat them, we have a more immediate stumbling block: many of the foods served up and even glorified by the wholesome-food movement are themselves chock full of fat and problem carbs.

Some wholesome foodies openly celebrate fat and problem carbs, insisting that the lack of processing magically renders them healthy. In singing the praises of clotted cream and lard-loaded cookies, for instance, a recent Wall Street Journal article by Ron Rosenbaum explained that “eating basic, earthy, fatty foods isn’t just a supreme experience of the senses—it can actually be good for you,” and that it’s “too easy to conflate eating fatty food with eating industrial, oil-fried junk food.” That’s right, we wouldn’t want to make the same mistake that all the cells in our bodies make. Pollan himself makes it clear in his writing that he has little problem with fat—as long as it’s not in food “your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize.”

Television food shows routinely feature revered chefs tossing around references to healthy eating, “wellness,” and farm-fresh ingredients, all the while spooning lard, cream, and sugar over everything in sight. (A study published last year in the British Medical Journal found that the recipes in the books of top TV chefs call for “significantly more” fat per portion than what’s contained in ready-to-eat supermarket meals.) Corporate wellness programs, one of the most promising avenues for getting the population to adopt healthy behaviors, are falling prey to this way of thinking as well. Last November, I attended a stress-management seminar for employees of a giant consulting company, and listened to a high-powered professional wellness coach tell the crowded room that it’s okay to eat anything as long as its plant or animal origins aren’t obscured by processing. Thus, she explained, potato chips are perfectly healthy, because they plainly come from potatoes, but Cheetos will make you sick and fat, because what plant or animal is a Cheeto? (For the record, typical potato chips and Cheetos have about equally nightmarish amounts of fat calories per ounce; Cheetos have fewer carbs, though more salt.)

The Pollanites seem confused about exactly what benefits their way of eating provides. All the railing about the fat, sugar, and salt engineered into industrial junk food might lead one to infer that wholesome food, having not been engineered, contains substantially less of them. But clearly you can take in obscene quantities of fat and problem carbs while eating wholesomely, and to judge by what’s sold at wholesome stores and restaurants, many people do. Indeed, the more converts and customers the wholesome-food movement’s purveyors seek, the stronger their incentive to emphasize foods that light up precisely the same pleasure centers as a 3 Musketeers bar. That just makes wholesome food stealthily obesogenic.

Hold on, you may be thinking. Leaving fat, sugar, and salt aside, what about all the nasty things that wholesome foods do not, by definition, contain and processed foods do? A central claim of the wholesome-food movement is that wholesome is healthier because it doesn’t have the artificial flavors, preservatives, other additives, or genetically modified ingredients found in industrialized food; because it isn’t subjected to the physical transformations that processed foods go through; and because it doesn’t sit around for days, weeks, or months, as industrialized food sometimes does. (This is the complaint against the McDonald’s smoothie, which contains artificial flavors and texture additives, and which is pre-mixed.)

The health concerns raised about processing itself—rather than the amount of fat and problem carbs in any given dish—are not, by and large, related to weight gain or obesity. That’s important to keep in mind, because obesity is, by an enormous margin, the largest health problem created by what we eat. But even putting that aside, concerns about processed food have been magnified out of all proportion.

Some studies have shown that people who eat wholesomely tend to be healthier than people who live on fast food and other processed food (particularly meat), but the problem with such studies is obvious: substantial nondietary differences exist between these groups, such as propensity to exercise, smoking rates, air quality, access to health care, and much more. (Some researchers say they’ve tried to control for these factors, but that’s a claim most scientists don’t put much faith in.) What’s more, the people in these groups are sometimes eating entirely different foods, not the same sorts of foods subjected to different levels of processing. It’s comparing apples to Whoppers, instead of Whoppers to hand-ground, grass-fed-beef burgers with heirloom tomatoes, garlic aioli, and artisanal cheese. For all these reasons, such findings linking food type and health are considered highly unreliable, and constantly contradict one another, as is true of most epidemiological studies that try to tackle broad nutritional questions.

The fact is, there is simply no clear, credible evidence that any aspect of food processing or storage makes a food uniquely unhealthy. The U.S. population does not suffer from a critical lack of any nutrient because we eat so much processed food. (Sure, health experts urge Americans to get more calcium, potassium, magnesium, fiber, and vitamins A, E, and C, and eating more produce and dairy is a great way to get them, but these ingredients are also available in processed foods, not to mention supplements.) Pollan’s “foodlike substances” are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (with some exceptions, which are regulated by other agencies), and their effects on health are further raked over by countless scientists who would get a nice career boost from turning up the hidden dangers in some common food-industry ingredient or technique, in part because any number of advocacy groups and journalists are ready to pounce on the slightest hint of risk.

The results of all the scrutiny of processed food are hardly scary, although some groups and writers try to make them appear that way. The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Food Additives Project, for example, has bemoaned the fact that the FDA directly reviews only about 70 percent of the ingredients found in food, permitting the rest to pass as “generally recognized as safe” by panels of experts convened by manufacturers. But the only actual risk the project calls out on its Web site or in its publications is a quote from a Times article noting that bromine, which has been in U.S. foods for eight decades, is regarded as suspicious by many because flame retardants containing bromine have been linked to health risks. There is no conclusive evidence that bromine itself is a threat.

In Pandora’s Lunchbox, Melanie Warner assiduously catalogs every concern that could possibly be raised about the health threats of food processing, leveling accusations so vague, weakly supported, tired, or insignificant that only someone already convinced of the guilt of processed food could find them troubling. While ripping the covers off the breakfast-cereal conspiracy, for example, Warner reveals that much of the nutritional value claimed by these products comes not from natural ingredients but from added vitamins that are chemically synthesized, which must be bad for us because, well, they’re chemically synthesized . It’s the tautology at the heart of the movement: processed foods are unhealthy because they aren’t natural, full stop.

In many respects, the wholesome-food movement veers awfully close to religion. To repeat: there is no hard evidence to back any health-risk claims about processed food—evidence, say, of the caliber of several studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that have traced food poisoning to raw milk, a product championed by some circles of the wholesome-food movement. “Until I hear evidence to the contrary, I think it’s reasonable to include processed food in your diet,” says Robert Kushner, a physician and nutritionist and a professor at Northwestern University’s medical school, where he is the clinical director of the Comprehensive Center on Obesity.

There may be other reasons to prefer wholesome food to the industrialized version. Often stirred into the vague stew of benefits attributed to wholesome food is the “sustainability” of its production—that is, its long-term impact on the planet. Small farms that don’t rely much on chemicals and heavy industrial equipment may be better for the environment than giant industrial farms—although that argument quickly becomes complicated by a variety of factors. For the purposes of this article, let’s simply stipulate that wholesome foods are environmentally superior. But let’s also agree that when it comes to prioritizing among food-related public-policy goals, we are likely to save and improve many more lives by focusing on cutting obesity—through any available means—than by trying to convert all of industrial agriculture into a vast constellation of small organic farms.

The impact of obesity on the chances of our living long, productive, and enjoyable lives has been so well documented at this point that I hate to drag anyone through the grim statistics again. But let me just toss out one recent dispatch from the world of obesity-havoc science: a study published in February in the journal Obesity found that obese young adults and middle-agers in the U.S. are likely to lose almost a decade of life on average, as compared with their non-obese counterparts. Given our obesity rates, that means Americans who are alive today can collectively expect to sacrifice 1 billion years to obesity. The study adds to a river of evidence suggesting that for the first time in modern history—and in spite of many health-related improvements in our environment, our health care, and our nondietary habits—our health prospects are worsening, mostly because of excess weight.

By all means, let’s protect the environment. But let’s not rule out the possibility of technologically enabled improvements to our diet—indeed, let’s not rule out any food—merely because we are pleased by images of pastoral family farms. Let’s first pick the foods that can most plausibly make us healthier, all things considered, and then figure out how to make them environmentally friendly.

II. Let Them Eat Kale

I’m a fan of many of Mark Bittman’s recipes. I shop at Whole Foods all the time. And I eat like many wholesome foodies, except I try to stay away from those many wholesome ingredients and dishes that are high in fat and problem carbs. What’s left are vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, poultry, and fish (none of them fried, thank you), which are often emphasized by many wholesome-food fans. In general, I find that the more-natural versions of these ingredients taste at least a bit better, and occasionally much better, than the industrialized versions. And despite the wholesome-food movement’s frequent and inexcusable obliviousness to the obesogenicity of many of its own foods, it deserves credit for paying more attention to those healthier ingredients than does Big Food.

Where the Pollanites get into real trouble—where their philosophy becomes so glib and wrongheaded that it is actually immoral—is in the claim that their style of food shopping and eating is the answer to the country’s weight problem. Helping me to indulge my taste for genuinely healthy wholesome foods are the facts that I’m relatively affluent and well educated, and that I’m surrounded by people who tend to take care with what they eat. Not only am I within a few minutes’ drive of three Whole Foods and two Trader Joe’s, I’m within walking distance of two other supermarkets and more than a dozen restaurants that offer bountiful healthy-eating options.

I am, in short, not much like the average obese person in America, and neither are the Pollanites. That person is relatively poor, does not read The Times or cookbook manifestos, is surrounded by people who eat junk food and are themselves obese, and stands a good chance of living in a food desert—an area where produce tends to be hard to find, of poor quality, or expensive.

The wholesome foodies don’t argue that obesity and class are unrelated, but they frequently argue that the obesity gap between the classes has been created by the processed-food industry, which, in the past few decades, has preyed mostly on the less affluent masses. Yet Lenard Lesser, a physician and an obesity researcher at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, says that can’t be so, because the obesity gap predates the fast-food industry and the dietary dominance of processed food. “The difference in obesity rates in low- and high-income groups was evident as far back as we have data, at least back through the 1960s,” he told me. One reason, some researchers have argued, is that after having had to worry, over countless generations, about getting enough food, poorer segments of society had little cultural bias against overindulging in food, or putting on excess pounds, as industrialization raised incomes and made rich food cheaply available.

The most obvious problem with the “let them eat kale” philosophy of affluent wholesome-food advocates involves the price and availability of wholesome food. Even if Whole Foods, Real Food Daily, or the Farmhouse weren’t three bus rides away for the working poor, and even if three ounces of Vegan Cheesy Salad Booster, a Sea Cake appetizer, and the vegetarian quiche weren’t laden with fat and problem carbs, few among them would be likely to shell out $5.99, $9.95, or $16, respectively, for those pricey treats.

A slew of start-ups are trying to find ways of producing fresh, local, unprocessed meals quickly and at lower cost. But could this food eventually be sold as cheaply, conveniently, and ubiquitously as today’s junky fast food? Not even according to Bittman, who explored the question in a recent New York Times Magazine article. Even if wholesome food caught on with the public at large, including the obese population, and even if poor and working-class people were willing to pay a premium for it, how long would it take to scale up from a handful of shops to the tens of thousands required to begin making a dent in the obesity crisis? How long would it take to create the thousands of local farms we’d need in order to provide these shops with fresh, unprocessed ingredients, even in cities?

Yet these hurdles can be waved away, if one only has the proper mind-set. Bittman argued two years ago in The Times that there’s no excuse for anyone, food-desert-bound or not, to eat fast food rather than wholesome food, because even if it’s not perfectly fresh and locally grown, lower-end wholesome food—when purchased judiciously at the supermarket and cooked at home—can be cheaper than fast food. Sure, there’s the matter of all the time, effort, schedule coordination, and ability it takes to shop, cook, serve, and clean up. But anyone who whines about that extra work, Bittman chided, just doesn’t want to give up their excessive TV watching. (An “important benefit of paying more for better-quality food is that you’re apt to eat less of it,” Pollan helpfully noted in his 2008 book, In Defense of Food .) It’s remarkable how easy it is to remake the disadvantaged in one’s own image.

L et’s assume for a moment that somehow America, food deserts and all, becomes absolutely lousy with highly affordable outlets for wholesome, locally sourced dishes that are high in vegetables, fruits, legumes, poultry, fish, and whole grains, and low in fat and problem carbs. What percentage of the junk-food-eating obese do we want to predict will be ready to drop their Big Macs, fries, and Cokes for grilled salmon on chard? We can all agree that many obese people find the former foods extremely enjoyable, and seem unable to control their consumption of them. Is greater availability of healthier food that pushes none of the same thrill buttons going to solve the problem?

Many Pollanites insist it will. “If the government came into these communities and installed Brita filters under their sinks, they’d drink water instead of Coke,” Lisa Powell, a professor of health policy and administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Institute for Health Research and Policy, told me. But experts who actually work with the obese see a more difficult transition, especially when busy schedules are thrown into the equation. “They won’t eat broccoli instead of french fries,” says Kelli Drenner, an obesity researcher at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas, which has about four fast-food restaurants per block along most of its main drag. “You try to make even a small change to school lunches, and parents and kids revolt.”

Hoping to gain some firsthand insight into the issue while in L.A., I drove away from the wholesome-food-happy, affluent, and mostly trim communities of the northwestern part of the city, and into East L.A. The largely Hispanic population there was nonaffluent and visibly plagued by obesity. On one street, I saw a parade of young children heading home from school. Perhaps a quarter of them were significantly overweight; several walked with a slow, waddling gait.

The area I found that’s most chockablock with commercial food options brackets the busy intersection of two main streets. However, like most areas I passed through nearby, this food scene was dominated not by fast-food restaurants but by bodegas (which, like most other types of convenience stores, are usually considered part of the low-income, food-desert landscape). I went into several of these mom-and-pop shops and saw pretty much the same thing in every one: A prominent display of extremely fatty-looking beef and pork, most of it fresh, though gigantic strips of fried pork skin often got pride of place. A lot of canned and boxed foods. Up front, shelves of candy and heavily processed snacks. A large set of display cases filled mostly with highly sugared beverages. And a small refrigerator case somewhere in the back sparsely populated with not-especially-fresh-looking fruits and vegetables. The bodega industry, too, seems to have plotted to addict communities to fat, sugar, and salt—unless, that is, they’re simply providing the foods that people like.

Various efforts have been made to redesign bodegas to emphasize healthier choices. I learned that one retooled bodega was nearby, and dropped in. It was cleaner and brighter than the others I’d seen, and a large produce case was near the entrance, brimming with an impressive selection of fresh-looking produce. The candy and other junky snack foods were relegated to a small set of shelves closer to the more dimly lit rear of the store. But I couldn’t help noticing that unlike most of the other bodegas I’d been to, this one was empty, except for me and a lone employee. I hung around, eventually buying a few items to assuage the employee’s growing suspicion. Finally, a young woman came in, made a beeline for the junk-food shelves, grabbed a pack of cupcakes, paid, and left.

It’s not exactly a scientific study, but we really shouldn’t need one to recognize that people aren’t going to change their ingrained, neurobiologically supercharged junk-eating habits just because someone dangles vegetables in front of them, farm-fresh or otherwise. Mark Bittman sees signs of victory in “the stories parents tell me of their kids booing as they drive by McDonald’s,” but it’s not hard to imagine which parents, which kids, and which neighborhoods those stories might involve. One study found that subsidizing the purchase of vegetables encouraged shoppers to buy more vegetables, but also more junk food with the money they saved; on balance, their diets did not improve. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently found that the aughts saw a significant drop in fruit intake, and no increase in vegetable consumption; Americans continue to fall far short of eating the recommended amounts of either. “Everyone’s mother and brother has been telling them to eat more fruit and vegetables forever, and the numbers are only getting worse,” says Steven Nickolas, who runs the Healthy Food Project in Scottsdale, Arizona. “We’re not going to solve this problem by telling people to eat unprocessed food.”

Trim, affluent Americans of course have a right to view dietary questions from their own perspective—that is, in terms of what they need to eat in order to add perhaps a few months onto the already healthy courses of their lives. The pernicious sleight of hand is in willfully confusing what might benefit them—small, elite minority that they are—with what would help most of society. The conversations they have among themselves in The Times , in best-selling books, and at Real Food Daily may not register with the working-class obese. But these conversations unquestionably distort the views of those who are in a position to influence what society does about the obesity problem.

III. The Food Revolution We Need

The one fast-food restaurant near that busy East L.A. intersection otherwise filled with bodegas was a Carl’s Jr. I went in and saw that the biggest and most prominent posters in the store were pushing a new grilled-cod sandwich. It actually looked pretty good, but it wasn’t quite lunchtime, and I just wanted a cup of coffee. I went to the counter to order it, but before I could say anything, the cashier greeted me and asked, “Would you like to try our new Charbroiled Atlantic Cod Fish Sandwich today?” Oh, well, sure, why not? (I asked her to hold the tartar sauce, which is mostly fat, but found out later that the sandwich is normally served with about half as much tartar sauce as the notoriously fatty Filet-O-Fish sandwich at McDonald’s, where the fish is battered and fried.) The sandwich was delicious. It was less than half the cost of the Sea Cake appetizer at Real Food Daily. It took less than a minute to prepare. In some ways, it was the best meal I had in L.A., and it was probably the healthiest.

We know perfectly well who within our society has developed an extraordinary facility for nudging the masses to eat certain foods, and for making those foods widely available in cheap and convenient forms. The Pollanites have led us to conflate the industrial processing of food with the adding of fat and sugar in order to hook customers, even while pushing many faux-healthy foods of their own. But why couldn’t Big Food’s processing and marketing genius be put to use on genuinely healthier foods, like grilled fish? Putting aside the standard objection that the industry has no interest in doing so—we’ll see later that in fact the industry has plenty of motivation for taking on this challenge—wouldn’t that present a more plausible answer to America’s junk-food problem than ordering up 50,000 new farmers’ markets featuring locally grown organic squash blossoms?

According to Lenard Lesser, of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, the food industry has mastered the art of using in-store and near-store promotions to shape what people eat. As Lesser and I drove down storied Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley and into far less affluent Oakland, leaving behind the Whole Foods Markets and sushi restaurants for gas-station markets and barbecued-rib stands, he pointed out the changes in the billboards. Whereas the last one we saw in Berkeley was for fruit juice, many in Oakland tout fast-food joints and their wares, including several featuring the Hot Mess Burger at Jack in the Box. Though Lesser noted that this forest of advertising may simply reflect Oakland residents’ preexisting preference for this type of food, he told me lab studies have indicated that the more signs you show people for a particular food product or dish, the more likely they are to choose it over others, all else being equal.

We went into a KFC and found ourselves traversing a maze of signage that put us face-to-face with garish images of various fried foods that presumably had some chicken somewhere deep inside them. “The more they want you to buy something, the bigger they make the image on the menu board,” Lesser explained. Here, what loomed largest was the $19.98 fried-chicken-and-corn family meal, which included biscuits and cake. A few days later, I noticed that McDonald’s places large placards showcasing desserts on the trash bins, apparently calculating that the best time to entice diners with sweets is when they think they’ve finished their meals.

Trying to get burger lovers to jump to grilled fish may already be a bit of a stretch—I didn’t see any of a dozen other customers buy the cod sandwich when I was at Carl’s Jr., though the cashier said it was selling reasonably well. Still, given the food industry’s power to tinker with and market food, we should not dismiss its ability to get unhealthy eaters—slowly, incrementally—to buy better food.

That brings us to the crucial question: Just how much healthier could fast-food joints and processed-food companies make their best-selling products without turning off customers? I put that question to a team of McDonald’s executives, scientists, and chefs who are involved in shaping the company’s future menus, during a February visit to McDonald’s surprisingly bucolic campus west of Chicago. By way of a partial answer, the team served me up a preview tasting of two major new menu items that had been under development in their test kitchens and high-tech sensory-testing labs for the past year, and which were rolled out to the public in April. The first was the Egg White Delight McMuffin ($2.65), a lower-calorie, less fatty version of the Egg McMuffin, with some of the refined flour in the original recipe replaced by whole-grain flour. The other was one of three new Premium McWraps ($3.99), crammed with grilled chicken and spring mix, and given a light coating of ranch dressing amped up with rice vinegar. Both items tasted pretty good (as do the versions in stores, I’ve since confirmed, though some outlets go too heavy on the dressing). And they were both lower in fat, sugar, and calories than not only many McDonald’s staples, but also much of the food served in wholesome restaurants or touted in wholesome cookbooks.

In fact, McDonald’s has quietly been making healthy changes for years, shrinking portion sizes, reducing some fats, trimming average salt content by more than 10 percent in the past couple of years alone, and adding fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and oatmeal to its menu. In May, the chain dropped its Angus third-pounders and announced a new line of quarter-pound burgers, to be served on buns containing whole grains. Outside the core fast-food customer base, Americans are becoming more health-conscious. Public backlash against fast food could lead to regulatory efforts, and in any case, the fast-food industry has every incentive to maintain broad appeal. “We think a lot about how we can bring nutritionally balanced meals that include enough protein, along with the tastes and satisfaction that have an appetite-tiding effect,” said Barbara Booth, the company’s director of sensory science.

Such steps are enormously promising, says Jamy Ard, an epidemiology and preventive-medicine researcher at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and a co-director of the Weight Management Center there. “Processed food is a key part of our environment, and it needs to be part of the equation,” he explains. “If you can reduce fat and calories by only a small amount in a Big Mac, it still won’t be a health food, but it wouldn’t be as bad, and that could have a huge impact on us.” Ard, who has been working for more than a decade with the obese poor, has little patience with the wholesome-food movement’s call to eliminate fast food in favor of farm-fresh goods. “It’s really naive,” he says. “Fast food became popular because it’s tasty and convenient and cheap. It makes a lot more sense to look for small, beneficial changes in that food than it does to hold out for big changes in what people eat that have no realistic chance of happening.”

According to a recent study, Americans get 11 percent of their calories, on average, from fast food—a number that’s almost certainly much higher among the less affluent overweight. As a result, the fast-food industry may be uniquely positioned to improve our diets. Research suggests that calorie counts in a meal can be trimmed by as much as 30 percent without eaters noticing—by, for example, reducing portion sizes and swapping in ingredients that contain more fiber and water. Over time, that could be much more than enough to literally tip the scales for many obese people. “The difference between losing weight and not losing weight,” says Robert Kushner, the obesity scientist and clinical director at Northwestern, “is a few hundred calories a day.”

Which raises a question: If McDonald’s is taking these sorts of steps, albeit in a slow and limited way, why isn’t it more loudly saying so to deflect criticism? While the company has heavily plugged the debut of its new egg-white sandwich and chicken wraps, the ads have left out even a mention of health, the reduced calories and fat, or the inclusion of whole grains. McDonald’s has practically kept secret the fact that it has also begun substituting whole-grain flour for some of the less healthy refined flour in its best-selling Egg McMuffin.

The explanation can be summed up in two words that surely strike fear into the hearts of all fast-food executives who hope to make their companies’ fare healthier: McLean Deluxe.

Among those who gleefully rank such things, the McLean Deluxe reigns as McDonald’s worst product failure of all time, eclipsing McPasta, the McHotdog, and the McAfrica (don’t ask). When I brought up the McLean Deluxe to the innovation team at McDonald’s, I faced the first and only uncomfortable silence of the day. Finally, Greg Watson, a senior vice president, cleared his throat and told me that neither he nor anyone else in the room was at the company at the time, and he didn’t know that much about it. “It sounds to me like it was ahead of its time,” he added. “If we had something like that in the future, we would never launch it like that again.”

Introduced in 1991, the McLean Deluxe was perhaps the boldest single effort the food industry has ever undertaken to shift the masses to healthier eating. It was supposed to be a healthier version of the Quarter Pounder, made with extra-lean beef infused with seaweed extract. It reportedly did reasonably well in early taste tests—for what it’s worth, my wife and I were big fans—and McDonald’s pumped the reduced-fat angle to the public for all it was worth. The general reaction varied from lack of interest to mockery to revulsion. The company gamely flogged the sandwich for five years before quietly removing it from the menu.

The McLean Deluxe was a sharp lesson to the industry, even if in some ways it merely confirmed what generations of parents have well known: if you want to turn off otherwise eager eaters to a dish, tell them it’s good for them. Recent studies suggest that calorie counts placed on menus have a negligible effect on food choices, and that the less-health-conscious might even use the information to steer clear of low-calorie fare—perhaps assuming that it tastes worse and is less satisfying, and that it’s worse value for their money. The result is a sense in the food industry that if it is going to sell healthier versions of its foods to the general public—and not just to that minority already sold on healthier eating—it is going to have to do it in a relatively sneaky way, emphasizing the taste appeal and not the health benefits. “People expect something to taste worse if they believe it’s healthy,” says Charles Spence, an Oxford University neuroscientist who specializes in how the brain perceives food. “And that expectation affects how it tastes to them, so it actually does taste worse.”

Thus McDonald’s silence on the nutritional profiles of its new menu items. “We’re not making any health claims,” Watson said. “We’re just saying it’s new, it tastes great, come on in and enjoy it. Maybe once the product is well seated with customers, we’ll change that message.” If customers learn that they can eat healthier foods at McDonald’s without even realizing it, he added, they’ll be more likely to try healthier foods there than at other restaurants. The same reasoning presumably explains why the promotions and ads for the Carl’s Jr. grilled-cod sandwich offer not a word related to healthfulness, and why there wasn’t a whiff of health cheerleading surrounding the turkey burger brought out earlier this year by Burger King (which is not yet calling the sandwich a permanent addition).

If the food industry is to quietly sell healthier products to its mainstream, mostly non-health-conscious customers, it must find ways to deliver the eating experience that fat and problem carbs provide in foods that have fewer of those ingredients. There is no way to do that with farm-fresh produce and wholesome meat, other than reducing portion size. But processing technology gives the food industry a potent tool for trimming unwanted ingredients while preserving the sensations they deliver.

I visited Fona International, a flavor-engineering company also outside Chicago, and learned that there are a battery of tricks for fooling and appeasing taste buds, which are prone to notice a lack of fat or sugar, or the presence of any of the various bitter, metallic, or otherwise unpleasant flavors that vegetables, fiber, complex carbs, and fat or sugar substitutes can impart to a food intended to appeal to junk-food eaters. Some 5,000 FDA-approved chemical compounds—which represent the base components of all known flavors—line the shelves that run alongside Fona’s huge labs. Armed with these ingredients and an array of state-of-the-art chemical-analysis and testing tools, Fona’s scientists and engineers can precisely control flavor perception. “When you reduce the sugar, fat, and salt in foods, you change the personality of the product,” said Robert Sobel, a chemist, who heads up research at the company. “We can restore it.”

For example, fat “cushions” the release of various flavors on the tongue, unveiling them gradually and allowing them to linger. When fat is removed, flavors tend to immediately inundate the tongue and then quickly flee, which we register as a much less satisfying experience. Fona’s experts can reproduce the “temporal profile” of the flavors in fattier foods by adding edible compounds derived from plants that slow the release of flavor molecules; by replacing the flavors with similarly flavored compounds that come on and leave more slowly; or by enlisting “phantom aromas” that create the sensation of certain tastes even when those tastes are not present on the tongue. (For example, the smell of vanilla can essentially mask reductions in sugar of up to 25 percent.) One triumph of this sort of engineering is the modern protein drink, a staple of many successful weight-loss programs and a favorite of those trying to build muscle. “Seven years ago they were unpalatable,” Sobel said. “Today we can mask the astringent flavors and eggy aromas by adding natural ingredients.”

I also visited Tic Gums in White Marsh, Maryland, a company that engineers textures into food products. Texture hasn’t received the attention that flavor has, noted Greg Andon, Tic’s boyish and ebullient president, whose family has run the company for three generations. The result, he said, is that even people in the food industry don’t have an adequate vocabulary for it. “They know what flavor you’re referring to when you say ‘forest floor,’ but all they can say about texture is ‘Can you make it more creamy?’ ” So Tic is inventing a vocabulary, breaking textures down according to properties such as “mouth coating” and “mouth clearing.” Wielding an arsenal of some 20 different “gums”—edible ingredients mostly found in tree sap, seeds, and other plant matter—Tic’s researchers can make low-fat foods taste, well, creamier; give the same full body that sugared drinks offer to sugar-free beverages; counter chalkiness and gloopiness; and help orchestrate the timing of flavor bursts. (Such approaches have nothing in common with the ill-fated Olestra, a fat-like compound engineered to pass undigested through the body, and billed in the late 1990s as a fat substitute in snack foods. It was made notorious by widespread anecdotal complaints of cramps and loose bowels, though studies seemed to contradict those claims.)

Fona and Tic, like most companies in their industry, won’t identify customers or product names on the record. But both firms showed me an array of foods and beverages that were under construction, so to speak, in the name of reducing calories, fat, and sugar while maintaining mass appeal. I’ve long hated the taste of low-fat dressing—I gave up on it a few years ago and just use vinegar—but Tic served me an in-development version of a low-fat salad dressing that was better than any I’ve ever had. Dozens of companies are doing similar work, as are the big food-ingredient manufacturers, such as ConAgra, whose products are in 97 percent of American homes, and whose whole-wheat flour is what McDonald’s is relying on for its breakfast sandwiches. Domino Foods, the sugar manufacturer, now sells a low-calorie combination of sugar and the nonsugar sweetener stevia that has been engineered by a flavor company to mask the sort of nonsugary tastes driving many consumers away from diet beverages and the like. “Stevia has a licorice note we were able to have taken out,” explains Domino Foods CEO Brian O’Malley.

High-tech anti-obesity food engineering is just warming up. Oxford’s Charles Spence notes that in addition to flavors and textures, companies are investigating ways to exploit a stream of insights that have been coming out of scholarly research about the neuroscience of eating. He notes, for example, that candy companies may be able to slip healthier ingredients into candy bars without anyone noticing, simply by loading these ingredients into the middle of the bar and leaving most of the fat and sugar at the ends of the bar. “We tend to make up our minds about how something tastes from the first and last bites, and don’t care as much what happens in between,” he explains. Some other potentially useful gimmicks he points out: adding weight to food packaging such as yogurt containers, which convinces eaters that the contents are rich with calories, even when they’re not; using chewy textures that force consumers to spend more time between bites, giving the brain a chance to register satiety; and using colors, smells, sounds, and packaging information to create the belief that foods are fatty and sweet even when they are not. Spence found, for example, that wine is perceived as 50 percent sweeter when consumed under a red light.

Researchers are also tinkering with food ingredients to boost satiety. Cargill has developed a starch derived from tapioca that gives dishes a refined-carb taste and mouthfeel, but acts more like fiber in the body—a feature that could keep the appetite from spiking later. “People usually think that processing leads to foods that digest too quickly, but we’ve been able to use processing to slow the digestion rate,” says Bruce McGoogan, who heads R&D for Cargill’s North American food-ingredient business. The company has also developed ways to reduce fat in beef patties, and to make baked goods using half the usual sugar and oil, all without heavily compromising taste and texture.

Other companies and research labs are trying to turn out healthier, more appealing foods by enlisting ultra-high pressure, nanotechnology, vacuums, and edible coatings. At the University of Massachusetts at Amherst’s Center for Foods for Health and Wellness, Fergus Clydesdale, the director of the school’s Food Science Policy Alliance—as well as a spry 70-something who’s happy to tick off all the processed food in his diet—showed me labs where researchers are looking into possibilities that would not only attack obesity but also improve health in other significant ways, for example by isolating ingredients that might lower the risk of cancer and concentrating them in foods. “When you understand foods at the molecular level,” he says, “there’s a lot you can do with food and health that we’re not doing now.”

IV. The Implacable Enemies of Healthier Processed Food

What’s not to like about these developments? Plenty, if you’ve bought into the notion that processing itself is the source of the unhealthfulness of our foods. The wholesome-food movement is not only talking up dietary strategies that are unlikely to help most obese Americans; it is, in various ways, getting in the way of strategies that could work better.

The Pollanites didn’t invent resistance to healthier popular foods, as the fates of the McLean Deluxe and Olestra demonstrate, but they’ve greatly intensified it. Fast food and junk food have their core customer base, and the wholesome-food gurus have theirs. In between sit many millions of Americans—the more the idea that processed food should be shunned no matter what takes hold in this group, the less incentive fast-food joints will have to continue edging away from the fat- and problem-carb-laden fare beloved by their most loyal customers to try to broaden their appeal.

Pollan has popularized contempt for “nutritionism,” the idea behind packing healthier ingredients into processed foods. In his view, the quest to add healthier ingredients to food isn’t a potential solution, it’s part of the problem. Food is healthy not when it contains healthy ingredients, he argues, but when it can be traced simply and directly to (preferably local) farms. As he resonantly put it in The Times in 2007: “If you’re concerned about your health, you should probably avoid food products that make health claims. Why? Because a health claim on a food product is a good indication that it’s not really food, and food is what you want to eat.”

In this way, wholesome-food advocates have managed to pre-damn the very steps we need the food industry to take, placing the industry in a no-win situation: If it maintains the status quo, then we need to stay away because its food is loaded with fat and sugar. But if it tries to moderate these ingredients, then it is deceiving us with nutritionism. Pollan explicitly counsels avoiding foods containing more than five ingredients, or any hard-to-pronounce or unfamiliar ingredients. This rule eliminates almost anything the industry could do to produce healthier foods that retain mass appeal—most of us wouldn’t get past xanthan gum—and that’s perfectly in keeping with his intention.

By placing wholesome eating directly at odds with healthier processed foods, the Pollanites threaten to derail the reformation of fast food just as it’s starting to gain traction. At McDonald’s, “Chef Dan”—that is, Dan Coudreaut, the executive chef and director of culinary innovation—told me of the dilemma the movement has caused him as he has tried to make the menu healthier. “Some want us to have healthier food, but others want us to have minimally processed ingredients, which can mean more fat,” he explained. “It’s becoming a balancing act for us.” That the chef with arguably the most influence in the world over the diet of the obese would even consider adding fat to his menu to placate wholesome foodies is a pretty good sign that something has gone terribly wrong with our approach to the obesity crisis.

Many people insist that the steps the food industry has already taken to offer less-obesogenic fare are no more than cynical ploys to fool customers into eating the same old crap under a healthy guise. In his 3,500-word New York Times Magazine article on the prospects for healthier fast food, Mark Bittman lauded a new niche of vegan chain restaurants while devoting just one line to the major “quick serve” restaurants’ contribution to better health: “I’m not talking about token gestures, like the McDonald’s fruit-and-yogurt parfait, whose calories are more than 50 percent sugar.” Never mind that 80 percent of a farm-fresh apple’s calories come from sugar; that almost any obesity expert would heartily approve of the yogurt parfait as a step in the right direction for most fast-food-dessert eaters; and that many of the desserts Bittman glorifies in his own writing make the parfait look like arugula, nutrition-wise. (His recipe for corn-and-blueberry crisp, for example, calls for adding two-thirds of a cup of brown sugar to a lot of other problem carbs, along with five tablespoons of butter.)