Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on May 9, 2024.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

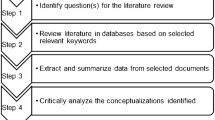

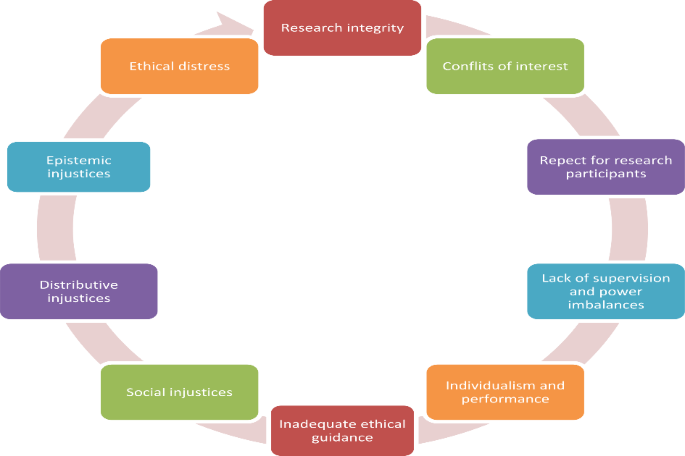

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

| Voluntary participation | Your participants are free to opt in or out of the study at any point in time. |

|---|---|

| Informed consent | Participants know the purpose, benefits, risks, and funding behind the study before they agree or decline to join. |

| Anonymity | You don’t know the identities of the participants. Personally identifiable data is not collected. |

| Confidentiality | You know who the participants are but you keep that information hidden from everyone else. You anonymize personally identifiable data so that it can’t be linked to other data by anyone else. |

| Potential for harm | Physical, social, psychological and all other types of harm are kept to an absolute minimum. |

| Results communication | You ensure your work is free of or research misconduct, and you accurately represent your results. |

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, May 09). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal

This article explores the ethical issues that may arise in your proposed study during your doctoral research degree.

What ethical principles apply when planning and conducting research?

Research ethics are the moral principles that govern how researchers conduct their studies (Wellcome Trust, 2014). As there are elements of uncertainty and risk involved in any study, every researcher has to consider how they can uphold these ethical principles and conduct the research in a way that protects the interests and welfare of participants and other stakeholders (such as organisations).

You will need to consider the ethical issues that might arise in your proposed study. Consideration of the fundamental ethical principles that underpin all research will help you to identify the key issues and how these could be addressed. As you are probably a practitioner who wants to undertake research within your workplace, consider how your role as an ‘insider’ influences how you will conduct your study. Think about the ethical issues that might arise when you become an insider researcher (for example, relating to trust, confidentiality and anonymity).

What key ethical principles do you think will be important when planning or conducting your research, particularly as an insider? Principles that come to mind might include autonomy, respect, dignity, privacy, informed consent and confidentiality. You may also have identified principles such as competence, integrity, wellbeing, justice and non-discrimination.

Key ethical issues that you will address as an insider researcher include:

- Gaining trust

- Avoiding coercion when recruiting colleagues or other participants (such as students or service users)

- Practical challenges relating to ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of organisations and staff or other participants.

(Heslop et al, 2018)

A fuller discussion of ethical principles is available from the British Psychological Society’s Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021).

You can also refer to guidance from the British Educational Research Association and the British Association for Applied Linguistics .

Ethical principles are essential for protecting the interests of research participants, including maximising the benefits and minimising any risks associated with taking part in a study. These principles describe ethical conduct which reflects the integrity of the researcher, promotes the wellbeing of participants and ensures high-quality research is conducted (Health Research Authority, 2022).

Research ethics is therefore not simply about gaining ethical approval for your study to be conducted. Research ethics relates to your moral conduct as a doctoral researcher and will apply throughout your study from design to dissemination (British Psychological Society, 2021). When you apply to undertake a doctorate, you will need to clearly indicate in your proposal that you understand these ethical principles and are committed to upholding them.

Where can I find ethical guidance and resources?

Professional bodies, learned societies, health and social care authorities, academic publications, Research Ethics Committees and research organisations provide a range of ethical guidance and resources. International codes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights underpin ethical frameworks (United Nations, 1948).

You may be aware of key legislation in your own country or the country where you plan to undertake the research, including laws relating to consent, data protection and decision-making capacity, for example, the Data Protection Act, 2018 (UK). If you want to find out more about becoming an ethical researcher, check out this Open University short course: Becoming an ethical researcher: Introduction and guidance: What is a badged course? - OpenLearn - Open University

You should be able to justify the research decisions you make. Utilising these resources will guide your ethical judgements when writing your proposal and ultimately when designing and conducting your research study. The Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (British Educational Research Association, 2018) identifies the key responsibilities you will have when you conduct your research, including the range of stakeholders that you will have responsibilities to, as follows:

- to your participants (e.g. to appropriately inform them, facilitate their participation and support them)

- clients, stakeholders and sponsors

- the community of educational or health and social care researchers

- for publication and dissemination

- your wellbeing and development

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) has emphasised the need to promote equality, diversity and inclusion when undertaking research, particularly to address long-standing social and health inequalities. Research should be informed by the diversity of people’s experiences and insights, so that it will lead to the development of practice that addresses genuine need. A commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion aims to eradicate prejudice and discrimination on the basis of an individual or group of individuals' protected characteristics such as sex (gender), disability, race, sexual orientation, in line with the Equality Act 2010.

The NIHR has produced guidance for enhancing the inclusion of ‘under-served groups’ when designing a research study (2020). Although the guidance refers to clinical research it is relevant to research more broadly.

You should consider how you will promote equality and diversity in your planned study, including through aspects such as your research topic or question, the methodology you will use, the participants you plan to recruit and how you will analyse and interpret your data.

What ethical issues do I need to consider when writing my research proposal?

You might be planning to undertake research in a health, social care, educational or other setting, including observations and interviews. The following prompts should help you to identify key ethical issues that you need to bear in mind when undertaking research in such settings.

1. Imagine you are a potential participant. Think about the questions and concerns that you might have:

- How would you feel if a researcher sat in your space and took notes, completed a checklist, or made an audio or film recording?

- What harm might a researcher cause by observing or interviewing you and others?

- What would you want to know about the researcher and ask them about the study before giving consent?

- When imagining you are the participant, how could the researcher make you feel more comfortable to be observed or interviewed?

2. Having considered the perspective of your potential participant, how would you take account of concerns such as privacy, consent, wellbeing and power in your research proposal?

[Adapted from OpenLearn course: Becoming an ethical researcher, Week 2 Activity 3: Becoming an ethical researcher - OpenLearn - Open University ]

The ethical issues to be considered will vary depending on your organisational context/role, the types of participants you plan to recruit (for example, children, adults with mental health problems), the research methods you will use, and the types of data you will collect. You will need to decide how to recruit your participants so you do not inappropriately exclude anyone. Consider what methods may be necessary to facilitate their voice and how you can obtain their consent to taking part or ensure that consent is obtained from someone else as necessary, for example, a parent in the case of a child.

You should also think about how to avoid imposing an unnecessary burden or costs on your participants. For example, by minimising the length of time they will have to commit to the study and by providing travel or other expenses. Identify the measures that you will take to store your participants’ data safely and maintain their confidentiality and anonymity when you report your findings. You could do this by storing interview and video recordings in a secure server and anonymising their names and those of their organisations using pseudonyms.

Professional codes such as the Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021) provide guidance on undertaking research with children. Being an ‘insider’ researching within your own organisation has advantages. However, you should also consider how this might impact on your research, such as power dynamics, consent, potential bias and any conflict of interest between your professional and researcher roles (Sapiro and Matthews, 2020).

How have other researchers addressed any ethical challenges?

The literature provides researchers’ accounts explaining how they addressed ethical challenges when undertaking studies. For example, Turcotte-Tremblay and McSween-Cadieux (2018) discuss strategies for protecting participants’ confidentiality when disseminating findings locally, such as undertaking fieldwork in multiple sites and providing findings in a generalised form. In addition, professional guidance includes case studies illustrating how ethical issues can be addressed, including when researching online forums (British Sociological Association, no date).

Watch the videos below and consider what insights the postgraduate researcher and supervisor provide regarding issues such as being an ‘insider researcher’, power relations, avoiding intrusion, maintaining participant anonymity and complying with research ethics and professional standards. How might their experiences inform the design and conduct of your own study?

Postgraduate researcher and supervisor talk about ethical considerations

Your thoughtful consideration of the ethical issues that might arise and how you would address these should enable you to propose an ethically informed study and conduct it in a responsible, fair and sensitive manner.

British Educational Research Association (2018) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Psychological Society (2021) Code of Human Research Ethics . Available at: https://cms.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/BPS%20Code%20of%20Human%20Research%20Ethics%20%281%29.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Sociological Association (2016) Researching online forums . Available at: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24834/j000208_researching_online_forums_-cs1-_v3.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Health Research Authority (2022) UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research . Available at: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/uk-policy-framework-health-and-social-care-research/#chiefinvestigators (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Heslop, C., Burns, S., Lobo, R. (2018) ‘Managing qualitative research as insider-research in small rural communities’, Rural and Remote Health , 18: pp. 4576.

Equality Act 2010, c. 15. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/introduction (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) . Available at: https://arc-kss.nihr.ac.uk/public-and-community-involvement/pcie-guide/how-to-do-pcie/equality-diversity-and-inclusion-edi (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (2020) Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: Guidance from INCLUDE project. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Sapiro, B. and Matthews, E. (2020) ‘Both Insider and Outsider. On Conducting Social Work Research in Mental Health Settings’, Advances in Social Work , 20(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.18060/23926

Turcotte-Tremblay, A. and McSween-Cadieux, E. (2018) ‘A reflection on the challenge of protecting confidentiality of participants when disseminating research results locally’, BMC Medical Ethics, 19(supplement 1), no. 45. Available at: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-018-0279-0

United Nations General Assembly (1948) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Resolution A/RES/217/A. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Drafted%20by%20representatives%20with%20different,all%20peoples%20and%20all%20nations . (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Wellcome Trust (2014) Ensuring your research is ethical: A guide for Extended Project Qualification students . Available at: https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wtp057673_0.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

More articles from the research proposal collection

Writing your research proposal

A doctoral research degree is the highest academic qualification that a student can achieve. The guidance provided in these articles will help you apply for one of the two main types of research degree offered by The Open University.

Level: 1 Introductory

Defining your research methodology

Your research methodology is the approach you will take to guide your research process and explain why you use particular methods. This article explains more.

Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview

The final article looks at writing your research proposal - from the introduction through to citations and referencing - as well as preparing for your interview.

Free courses on postgraduate study

Are you ready for postgraduate study?

This free course, Are you ready for postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and ensure you are ready to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Succeeding in postgraduate study

This free course, Succeeding in postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

This free OpenLearn course is for psychology students and graduates who are interested in PhD study at some future point. Even if you have met PhD students and heard about their projects, it is likely that you have only a vague idea of what PhD study entails. This course is intended to give you more information.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 27 June 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Pebbles balance on a stone see-saw' - Copyright: Photo 51106733 / Balance © Anatoli Styf | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Camera equipment set up filming a man talking' - Copyright: Photo 42631221 © Gabriel Robledo | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Applying to study for a PhD in psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Succeeding in postgraduate study' - Copyright: © Everste/Getty Images

- Image 'Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal' - Copyright: Photo 50384175 / Children Playing © Lenutaidi | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview' - Copyright: Photo 133038259 / Black Student © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Defining your research methodology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Writing your research proposal' - Copyright free

- Image 'Are you ready for postgraduate study?' - Copyright free

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Activities /

Ensuring ethical standards and procedures for research with human beings

Research ethics govern the standards of conduct for scientific researchers. It is important to adhere to ethical principles in order to protect the dignity, rights and welfare of research participants. As such, all research involving human beings should be reviewed by an ethics committee to ensure that the appropriate ethical standards are being upheld. Discussion of the ethical principles of beneficence, justice and autonomy are central to ethical review.

WHO works with Member States and partners to promote ethical standards and appropriate systems of review for any course of research involving human subjects. Within WHO, the Research Ethics Review Committee (ERC) ensures that WHO only supports research of the highest ethical standards. The ERC reviews all research projects involving human participants supported either financially or technically by WHO. The ERC is guided in its work by the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (1964), last updated in 2013, as well as the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS 2016).

WHO releases AI ethics and governance guidance for large multi-modal models

Call for proposals: WHO project on ethical climate and health research

Call for applications: Ethical issues arising in research into health and climate change

Research Ethics Review Committee

Standards and operational guidance for ethics review of health-related research with...

WHO tool for benchmarking ethics oversight of health-related research involving human...

Related activities

Developing normative guidance to address ethical challenges in global health

Supporting countries to manage ethical issues during outbreaks and emergencies

Engaging the global community in health ethics

Building ethics capacity

Framing the ethics of public health surveillance

Related health topics

Global health ethics

Human genome editing

Related teams

Related links

- International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. pdf, 1.55Mb

- International ethical guidelines for epidemiological studies Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. pdf, 634Kb

- World Medical Association: Declaration of Helsinki

- European Group on Ethics

- Directive 2001/20/ec of the European Parliament and of the Council pdf, 152Kb

- Council of Europe (Oviedo Convention - Protocol on biomedical research)

- Nuffield Council: The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on 7 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 6 July 2024.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviours, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to:

- Protect the rights of research participants

- Enhance research validity

- Maintain scientific integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research aims with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

| Voluntary participation | Your participants are free to opt in or out of the study at any point in time. |

|---|---|

| Informed consent | Participants know the purpose, benefits, risks, and funding behind the study before they agree or decline to join. |

| Anonymity | You don’t know the identities of the participants. Personally identifiable data is not collected. |

| Confidentiality | You know who the participants are but keep that information hidden from everyone else. You anonymise personally identifiable data so that it can’t be linked to other data by anyone else. |

| Potential for harm | Physical, social, psychological, and all other types of harm are kept to an absolute minimum. |

| Results communication | You ensure your work is free of plagiarism or research misconduct, and you accurately represent your results. |

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process, so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

- What the study is about

- The risks and benefits of taking part

- How long the study will take

- Your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information – for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymise data collection. For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymisation is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants, but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study, as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources, counselling, or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine scientific integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information – for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, July 05). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/ethical-considerations/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Your environment. your health., what is ethics in research & why is it important, by david b. resnik, j.d., ph.d..

December 23, 2020

The ideas and opinions expressed in this essay are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of the NIH, NIEHS, or US government.

When most people think of ethics (or morals), they think of rules for distinguishing between right and wrong, such as the Golden Rule ("Do unto others as you would have them do unto you"), a code of professional conduct like the Hippocratic Oath ("First of all, do no harm"), a religious creed like the Ten Commandments ("Thou Shalt not kill..."), or a wise aphorisms like the sayings of Confucius. This is the most common way of defining "ethics": norms for conduct that distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable behavior.

Most people learn ethical norms at home, at school, in church, or in other social settings. Although most people acquire their sense of right and wrong during childhood, moral development occurs throughout life and human beings pass through different stages of growth as they mature. Ethical norms are so ubiquitous that one might be tempted to regard them as simple commonsense. On the other hand, if morality were nothing more than commonsense, then why are there so many ethical disputes and issues in our society?

Alternatives to Animal Testing

Alternative test methods are methods that replace, reduce, or refine animal use in research and testing

Learn more about Environmental science Basics

One plausible explanation of these disagreements is that all people recognize some common ethical norms but interpret, apply, and balance them in different ways in light of their own values and life experiences. For example, two people could agree that murder is wrong but disagree about the morality of abortion because they have different understandings of what it means to be a human being.

Most societies also have legal rules that govern behavior, but ethical norms tend to be broader and more informal than laws. Although most societies use laws to enforce widely accepted moral standards and ethical and legal rules use similar concepts, ethics and law are not the same. An action may be legal but unethical or illegal but ethical. We can also use ethical concepts and principles to criticize, evaluate, propose, or interpret laws. Indeed, in the last century, many social reformers have urged citizens to disobey laws they regarded as immoral or unjust laws. Peaceful civil disobedience is an ethical way of protesting laws or expressing political viewpoints.

Another way of defining 'ethics' focuses on the disciplines that study standards of conduct, such as philosophy, theology, law, psychology, or sociology. For example, a "medical ethicist" is someone who studies ethical standards in medicine. One may also define ethics as a method, procedure, or perspective for deciding how to act and for analyzing complex problems and issues. For instance, in considering a complex issue like global warming , one may take an economic, ecological, political, or ethical perspective on the problem. While an economist might examine the cost and benefits of various policies related to global warming, an environmental ethicist could examine the ethical values and principles at stake.

See ethics in practice at NIEHS

Read latest updates in our monthly Global Environmental Health Newsletter

Many different disciplines, institutions , and professions have standards for behavior that suit their particular aims and goals. These standards also help members of the discipline to coordinate their actions or activities and to establish the public's trust of the discipline. For instance, ethical standards govern conduct in medicine, law, engineering, and business. Ethical norms also serve the aims or goals of research and apply to people who conduct scientific research or other scholarly or creative activities. There is even a specialized discipline, research ethics, which studies these norms. See Glossary of Commonly Used Terms in Research Ethics and Research Ethics Timeline .

There are several reasons why it is important to adhere to ethical norms in research. First, norms promote the aims of research , such as knowledge, truth, and avoidance of error. For example, prohibitions against fabricating , falsifying, or misrepresenting research data promote the truth and minimize error.

Join an NIEHS Study

See how we put research Ethics to practice.

Visit Joinastudy.niehs.nih.gov to see the various studies NIEHS perform.

Second, since research often involves a great deal of cooperation and coordination among many different people in different disciplines and institutions, ethical standards promote the values that are essential to collaborative work , such as trust, accountability, mutual respect, and fairness. For example, many ethical norms in research, such as guidelines for authorship , copyright and patenting policies , data sharing policies, and confidentiality rules in peer review, are designed to protect intellectual property interests while encouraging collaboration. Most researchers want to receive credit for their contributions and do not want to have their ideas stolen or disclosed prematurely.

Third, many of the ethical norms help to ensure that researchers can be held accountable to the public . For instance, federal policies on research misconduct, conflicts of interest, the human subjects protections, and animal care and use are necessary in order to make sure that researchers who are funded by public money can be held accountable to the public.

Fourth, ethical norms in research also help to build public support for research. People are more likely to fund a research project if they can trust the quality and integrity of research.

Finally, many of the norms of research promote a variety of other important moral and social values , such as social responsibility, human rights, animal welfare, compliance with the law, and public health and safety. Ethical lapses in research can significantly harm human and animal subjects, students, and the public. For example, a researcher who fabricates data in a clinical trial may harm or even kill patients, and a researcher who fails to abide by regulations and guidelines relating to radiation or biological safety may jeopardize his health and safety or the health and safety of staff and students.

Codes and Policies for Research Ethics

Given the importance of ethics for the conduct of research, it should come as no surprise that many different professional associations, government agencies, and universities have adopted specific codes, rules, and policies relating to research ethics. Many government agencies have ethics rules for funded researchers.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Singapore Statement on Research Integrity

- American Chemical Society, The Chemist Professional’s Code of Conduct

- Code of Ethics (American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science)

- American Psychological Association, Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

- Statement on Professional Ethics (American Association of University Professors)

- Nuremberg Code

- World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki

Ethical Principles

The following is a rough and general summary of some ethical principles that various codes address*:

Strive for honesty in all scientific communications. Honestly report data, results, methods and procedures, and publication status. Do not fabricate, falsify, or misrepresent data. Do not deceive colleagues, research sponsors, or the public.

Objectivity

Strive to avoid bias in experimental design, data analysis, data interpretation, peer review, personnel decisions, grant writing, expert testimony, and other aspects of research where objectivity is expected or required. Avoid or minimize bias or self-deception. Disclose personal or financial interests that may affect research.

Keep your promises and agreements; act with sincerity; strive for consistency of thought and action.

Carefulness

Avoid careless errors and negligence; carefully and critically examine your own work and the work of your peers. Keep good records of research activities, such as data collection, research design, and correspondence with agencies or journals.

Share data, results, ideas, tools, resources. Be open to criticism and new ideas.

Transparency

Disclose methods, materials, assumptions, analyses, and other information needed to evaluate your research.

Accountability

Take responsibility for your part in research and be prepared to give an account (i.e. an explanation or justification) of what you did on a research project and why.

Intellectual Property

Honor patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. Do not use unpublished data, methods, or results without permission. Give proper acknowledgement or credit for all contributions to research. Never plagiarize.

Confidentiality

Protect confidential communications, such as papers or grants submitted for publication, personnel records, trade or military secrets, and patient records.

Responsible Publication

Publish in order to advance research and scholarship, not to advance just your own career. Avoid wasteful and duplicative publication.

Responsible Mentoring

Help to educate, mentor, and advise students. Promote their welfare and allow them to make their own decisions.

Respect for Colleagues

Respect your colleagues and treat them fairly.

Social Responsibility

Strive to promote social good and prevent or mitigate social harms through research, public education, and advocacy.

Non-Discrimination

Avoid discrimination against colleagues or students on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, or other factors not related to scientific competence and integrity.

Maintain and improve your own professional competence and expertise through lifelong education and learning; take steps to promote competence in science as a whole.

Know and obey relevant laws and institutional and governmental policies.

Animal Care

Show proper respect and care for animals when using them in research. Do not conduct unnecessary or poorly designed animal experiments.

Human Subjects protection

When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy; take special precautions with vulnerable populations; and strive to distribute the benefits and burdens of research fairly.

* Adapted from Shamoo A and Resnik D. 2015. Responsible Conduct of Research, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press).

Ethical Decision Making in Research

Although codes, policies, and principles are very important and useful, like any set of rules, they do not cover every situation, they often conflict, and they require interpretation. It is therefore important for researchers to learn how to interpret, assess, and apply various research rules and how to make decisions and act ethically in various situations. The vast majority of decisions involve the straightforward application of ethical rules. For example, consider the following case:

The research protocol for a study of a drug on hypertension requires the administration of the drug at different doses to 50 laboratory mice, with chemical and behavioral tests to determine toxic effects. Tom has almost finished the experiment for Dr. Q. He has only 5 mice left to test. However, he really wants to finish his work in time to go to Florida on spring break with his friends, who are leaving tonight. He has injected the drug in all 50 mice but has not completed all of the tests. He therefore decides to extrapolate from the 45 completed results to produce the 5 additional results.

Many different research ethics policies would hold that Tom has acted unethically by fabricating data. If this study were sponsored by a federal agency, such as the NIH, his actions would constitute a form of research misconduct , which the government defines as "fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism" (or FFP). Actions that nearly all researchers classify as unethical are viewed as misconduct. It is important to remember, however, that misconduct occurs only when researchers intend to deceive : honest errors related to sloppiness, poor record keeping, miscalculations, bias, self-deception, and even negligence do not constitute misconduct. Also, reasonable disagreements about research methods, procedures, and interpretations do not constitute research misconduct. Consider the following case:

Dr. T has just discovered a mathematical error in his paper that has been accepted for publication in a journal. The error does not affect the overall results of his research, but it is potentially misleading. The journal has just gone to press, so it is too late to catch the error before it appears in print. In order to avoid embarrassment, Dr. T decides to ignore the error.

Dr. T's error is not misconduct nor is his decision to take no action to correct the error. Most researchers, as well as many different policies and codes would say that Dr. T should tell the journal (and any coauthors) about the error and consider publishing a correction or errata. Failing to publish a correction would be unethical because it would violate norms relating to honesty and objectivity in research.

There are many other activities that the government does not define as "misconduct" but which are still regarded by most researchers as unethical. These are sometimes referred to as " other deviations " from acceptable research practices and include:

- Publishing the same paper in two different journals without telling the editors

- Submitting the same paper to different journals without telling the editors

- Not informing a collaborator of your intent to file a patent in order to make sure that you are the sole inventor

- Including a colleague as an author on a paper in return for a favor even though the colleague did not make a serious contribution to the paper

- Discussing with your colleagues confidential data from a paper that you are reviewing for a journal

- Using data, ideas, or methods you learn about while reviewing a grant or a papers without permission

- Trimming outliers from a data set without discussing your reasons in paper

- Using an inappropriate statistical technique in order to enhance the significance of your research

- Bypassing the peer review process and announcing your results through a press conference without giving peers adequate information to review your work

- Conducting a review of the literature that fails to acknowledge the contributions of other people in the field or relevant prior work

- Stretching the truth on a grant application in order to convince reviewers that your project will make a significant contribution to the field

- Stretching the truth on a job application or curriculum vita

- Giving the same research project to two graduate students in order to see who can do it the fastest

- Overworking, neglecting, or exploiting graduate or post-doctoral students

- Failing to keep good research records

- Failing to maintain research data for a reasonable period of time

- Making derogatory comments and personal attacks in your review of author's submission

- Promising a student a better grade for sexual favors

- Using a racist epithet in the laboratory

- Making significant deviations from the research protocol approved by your institution's Animal Care and Use Committee or Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research without telling the committee or the board

- Not reporting an adverse event in a human research experiment

- Wasting animals in research

- Exposing students and staff to biological risks in violation of your institution's biosafety rules

- Sabotaging someone's work

- Stealing supplies, books, or data

- Rigging an experiment so you know how it will turn out

- Making unauthorized copies of data, papers, or computer programs

- Owning over $10,000 in stock in a company that sponsors your research and not disclosing this financial interest

- Deliberately overestimating the clinical significance of a new drug in order to obtain economic benefits

These actions would be regarded as unethical by most scientists and some might even be illegal in some cases. Most of these would also violate different professional ethics codes or institutional policies. However, they do not fall into the narrow category of actions that the government classifies as research misconduct. Indeed, there has been considerable debate about the definition of "research misconduct" and many researchers and policy makers are not satisfied with the government's narrow definition that focuses on FFP. However, given the huge list of potential offenses that might fall into the category "other serious deviations," and the practical problems with defining and policing these other deviations, it is understandable why government officials have chosen to limit their focus.

Finally, situations frequently arise in research in which different people disagree about the proper course of action and there is no broad consensus about what should be done. In these situations, there may be good arguments on both sides of the issue and different ethical principles may conflict. These situations create difficult decisions for research known as ethical or moral dilemmas . Consider the following case:

Dr. Wexford is the principal investigator of a large, epidemiological study on the health of 10,000 agricultural workers. She has an impressive dataset that includes information on demographics, environmental exposures, diet, genetics, and various disease outcomes such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and ALS. She has just published a paper on the relationship between pesticide exposure and PD in a prestigious journal. She is planning to publish many other papers from her dataset. She receives a request from another research team that wants access to her complete dataset. They are interested in examining the relationship between pesticide exposures and skin cancer. Dr. Wexford was planning to conduct a study on this topic.

Dr. Wexford faces a difficult choice. On the one hand, the ethical norm of openness obliges her to share data with the other research team. Her funding agency may also have rules that obligate her to share data. On the other hand, if she shares data with the other team, they may publish results that she was planning to publish, thus depriving her (and her team) of recognition and priority. It seems that there are good arguments on both sides of this issue and Dr. Wexford needs to take some time to think about what she should do. One possible option is to share data, provided that the investigators sign a data use agreement. The agreement could define allowable uses of the data, publication plans, authorship, etc. Another option would be to offer to collaborate with the researchers.

The following are some step that researchers, such as Dr. Wexford, can take to deal with ethical dilemmas in research:

What is the problem or issue?

It is always important to get a clear statement of the problem. In this case, the issue is whether to share information with the other research team.

What is the relevant information?

Many bad decisions are made as a result of poor information. To know what to do, Dr. Wexford needs to have more information concerning such matters as university or funding agency or journal policies that may apply to this situation, the team's intellectual property interests, the possibility of negotiating some kind of agreement with the other team, whether the other team also has some information it is willing to share, the impact of the potential publications, etc.

What are the different options?

People may fail to see different options due to a limited imagination, bias, ignorance, or fear. In this case, there may be other choices besides 'share' or 'don't share,' such as 'negotiate an agreement' or 'offer to collaborate with the researchers.'

How do ethical codes or policies as well as legal rules apply to these different options?

The university or funding agency may have policies on data management that apply to this case. Broader ethical rules, such as openness and respect for credit and intellectual property, may also apply to this case. Laws relating to intellectual property may be relevant.

Are there any people who can offer ethical advice?

It may be useful to seek advice from a colleague, a senior researcher, your department chair, an ethics or compliance officer, or anyone else you can trust. In the case, Dr. Wexford might want to talk to her supervisor and research team before making a decision.

After considering these questions, a person facing an ethical dilemma may decide to ask more questions, gather more information, explore different options, or consider other ethical rules. However, at some point he or she will have to make a decision and then take action. Ideally, a person who makes a decision in an ethical dilemma should be able to justify his or her decision to himself or herself, as well as colleagues, administrators, and other people who might be affected by the decision. He or she should be able to articulate reasons for his or her conduct and should consider the following questions in order to explain how he or she arrived at his or her decision:

- Which choice will probably have the best overall consequences for science and society?

- Which choice could stand up to further publicity and scrutiny?

- Which choice could you not live with?

- Think of the wisest person you know. What would he or she do in this situation?

- Which choice would be the most just, fair, or responsible?

After considering all of these questions, one still might find it difficult to decide what to do. If this is the case, then it may be appropriate to consider others ways of making the decision, such as going with a gut feeling or intuition, seeking guidance through prayer or meditation, or even flipping a coin. Endorsing these methods in this context need not imply that ethical decisions are irrational, however. The main point is that human reasoning plays a pivotal role in ethical decision-making but there are limits to its ability to solve all ethical dilemmas in a finite amount of time.

Promoting Ethical Conduct in Science

Do U.S. research institutions meet or exceed federal mandates for instruction in responsible conduct of research? A national survey

Read about U.S. research instutuins follow federal manadates for ethics in research

Learn more about NIEHS Research

Most academic institutions in the US require undergraduate, graduate, or postgraduate students to have some education in the responsible conduct of research (RCR) . The NIH and NSF have both mandated training in research ethics for students and trainees. Many academic institutions outside of the US have also developed educational curricula in research ethics

Those of you who are taking or have taken courses in research ethics may be wondering why you are required to have education in research ethics. You may believe that you are highly ethical and know the difference between right and wrong. You would never fabricate or falsify data or plagiarize. Indeed, you also may believe that most of your colleagues are highly ethical and that there is no ethics problem in research..

If you feel this way, relax. No one is accusing you of acting unethically. Indeed, the evidence produced so far shows that misconduct is a very rare occurrence in research, although there is considerable variation among various estimates. The rate of misconduct has been estimated to be as low as 0.01% of researchers per year (based on confirmed cases of misconduct in federally funded research) to as high as 1% of researchers per year (based on self-reports of misconduct on anonymous surveys). See Shamoo and Resnik (2015), cited above.

Clearly, it would be useful to have more data on this topic, but so far there is no evidence that science has become ethically corrupt, despite some highly publicized scandals. Even if misconduct is only a rare occurrence, it can still have a tremendous impact on science and society because it can compromise the integrity of research, erode the public’s trust in science, and waste time and resources. Will education in research ethics help reduce the rate of misconduct in science? It is too early to tell. The answer to this question depends, in part, on how one understands the causes of misconduct. There are two main theories about why researchers commit misconduct. According to the "bad apple" theory, most scientists are highly ethical. Only researchers who are morally corrupt, economically desperate, or psychologically disturbed commit misconduct. Moreover, only a fool would commit misconduct because science's peer review system and self-correcting mechanisms will eventually catch those who try to cheat the system. In any case, a course in research ethics will have little impact on "bad apples," one might argue.