Does Parent Involvement Really Help Students? Here’s What the Research Says

- Share article

Parental involvement has been a top priority for school leaders for decades, and research shows that it can make a major difference in student outcomes.

But a parents’ rights movement that has captured headlines over the past few years and become a major political force has painted a particular picture of what parents’ involvement in their children’s education looks like.

Policies that have passed in a number of individual school districts, states, and the U.S. House have spelled out parents’ rights to inspect curriculum materials and withdraw their children from lessons they deem objectionable; restricted teaching about race, gender identity, and sexuality; and resulted in the removal of books from school libraries, including many with LGBTQ+ characters and protagonists of color.

The parents’ rights movement has been divisive and attracted the ire of some teachers who feel censored. But it has also opened up the conversation around parent involvement in school, said Vito Borrello, executive director of the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement.

And that’s a good thing, he said.

“The parents’ rights bills in and of themselves, I wouldn’t suggest are entirely focused on best practice family engagement,” said Borrello, whose group works to advance effective family, school, and community engagement policies and practices. “However, what the parents’ rights bills have done is elevated the important role that parents have in their child’s education.”

For decades, research from around the world has shown that parents’ involvement in and engagement with their child’s education—including through parent-teacher conferences, parent-teacher organizations, school events, and at-home discussions about school—can lead to higher student achievement and better social-emotional outcomes.

Here are five takeaways from the research.

1. Studies show more parental involvement leads to improved academic outcomes

When parents are involved in their children’s schooling, students show higher academic achievement, school engagement, and motivation, according to a 2019 American Psychological Association review of 448 independent studies on parent involvement.

A 2005 study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Center on School, Family and Community Partnerships , for example, showed that school practices encouraging families to support their child’s math learning at home led to higher percentages of students scoring at or above proficiency on standardized math tests.

And research shows that parent involvement with reading activities has a positive impact on reading achievement, language comprehension, and expressive language skills, as well as students’ interest in reading, attitudes toward reading, and level of attention in the classroom, according to a research summary by the National Literacy Trust.

“When parents become involved at school by, for example, attending events such as open houses or volunteering in the classroom, they build social networks that can provide useful information, connections to school personnel (e.g., teachers), or strategies for enhancing children’s achievement,” the APA research review said. “In turn, parents with heightened social capital are better equipped to support their children in succeeding in school as they are able to call on resources (e.g., asking a teacher to spend extra time helping their children) and utilize information they have gathered (e.g., knowing when and how their children should complete their homework).”

2. Parent involvement changes social-emotional outcomes, too

The APA study showed that not only does parental involvement lead to improved academic outcomes, but it also has a positive impact on students’ social and emotional skills and decreases instances of delinquency.

That finding also applies internationally.

A 2014 International Education Studies report on parental involvement among 9th and 10th graders in Jordan showed that parental involvement had a positive impact on students’ emotional engagement in school. That means students with more involved parents are more likely to have fun, enjoy school, have high self-esteem, and perceive school as a satisfying experience.

And when parents visit their children’s school, that contributes to a sense of safety among the students, ultimately improving school engagement, the study said. Although conducted in Jordan, the study provides insight into how parental involvement affects students’ social-emotional development in other countries, including the United States.

Parent involvement also gives teachers the tools to better support their students, Borrello said.

“When teachers understand what their students are going through personally and at home and any challenges they may have, then that improves their teaching,” he said. “They’re able to support their student in ways they wouldn’t be able to otherwise.”

3. Not all parental involvement is created equal

Different levels and types of parent involvement led to varying outcomes for students, according to the American Psychological Association study.

For example, school-based involvement, such as participation in parent-teacher conferences, open houses, and other school events, had a positive impact on academics in preschool, middle school, and high school, but the size of the impact was much lower in high school than in preschool. That may be because parents have fewer opportunities to be involved in the high school environment than in younger students’ classrooms where parents might volunteer.

At-home discussions and encouragement surrounding school also have a positive impact on students’ academic achievement at all developmental stages, with that type of parent involvement being most effective for high schoolers, according to the study. Reading with children and taking them to the library have a positive impact as well.

But one common form of parental involvement, helping kids with their homework, was shown to have little impact on students’ academic achievement.

In fact, homework help had a small negative impact on student achievement, but positive impacts on student motivation and engagement in school, according to the APA study.

The research shows the value of encouraging parents to be involved in their student’s learning at home, and not just attending school events, Borrello said.

“In the past, schools either had an event that wasn’t connected to learning or only measured the engagement of a family based on how often they came to the school,” he said. “What families are doing to create an environment of learning and supporting learning at home, is probably even more important than how many times they’re coming to school.”

4. Results of parent involvement don’t discriminate based on race or socioeconomics

Research has shown a consensus that family and parent involvement in schools leads to better outcomes regardless of a family’s ethnic background or socioeconomic status.

Parent involvement has led to higher academic outcomes both for children from low and higher socioeconomic status families.

When comparing the impact of parent involvement on students of different races and ethnicities, the APA found that school-based involvement had a positive impact on academics among Black, Asian, white, and Hispanic children, with a stronger impact on Black and white families than families from other demographics. The finding also extended internationally, with similar effects on children outside of the United States.

5. Schools can encourage parent involvement in person and at home

Parent involvement doesn’t have to end with parent-teacher conferences. There are many ways for schools to encourage parents to be more involved both in school and at home, Borrello said.

The best way to start, he said, is by creating a school culture that is welcoming to families.

“That starts with the principal, and that starts with school leadership that is welcoming to families, from how they’re engaging parents in the classroom to what policies they have in schools to welcome families,” Borrello said.

Parent gathering spaces or rooms in school buildings, scheduled parent engagement meetings and office hours, and at-school events held outside of the school day are all good places to start, Borrello said. From there, schools can work to include parents in more decision-making, give parents resources to support learning at home, and equip teachers with the tools to engage and connect with parents.

“If the school is not welcoming and families don’t feel welcome at the school, then you’re not going to get them to come to school no matter what you do,” Borrello said. “Then it’s really thinking about who you’re creating those relationships with families so that they can be heard.”

Coverage of strategies for advancing the opportunities for students most in need, including those from low-income families and communities, is supported by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation, at www.waltonk12.org . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the August 16, 2023 edition of Education Week as Does Parent Involvement Really Help Students? 5 Key Takeaways Based on The Research

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Parental Involvement in Education

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2015

- Cite this reference work entry

- Velma LaPoint 2 ,

- Jo-Anne Manswell Butty 3 ,

- Cheryl Danzy 4 &

- Charlynn Small 5

369 Accesses

Nationally, there have been continuous calls for and an emphasis on improving the academic achievement and social competence of students in United States (U.S.) schools. Parental involvement in education continues to receive national attention as one type of school and community partnership program that can improve student academic achievement and social competence. Although parents, especially mothers, have always been involved in education, parental involvement in education has changed over time in its expression and emphasis in certain ethnic groups. Over the past 20 years there has been an emphasis on the need for parental involvement in education which has resulted in a proliferation of parental involvement programs and the need to evaluate their effectiveness. Further, there are issues relating to cultural diversity in parental involvement in education, types of parental involvement in education, and whether these are unequivocally required for students to achieve high standards...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Suggested Reading

Barge, J., & Loges, W. (2003). Parent, student, and teacher perceptions of parental involvement. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 31 , 140–163.

Article Google Scholar

Christenson, S. L., & Sheridan, S. M. (2001). School and families: Creating essential connections for learning . New York: Guilford.

Google Scholar

Jeynes, W. (2003). A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children’s academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 35 , 202–218.

Sanders, M. G. (2001). Schools, families, and communities: Partnerships for success . Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Wright, K., & Stegelin, D. A. (2003). Building school and community partnerships through parent involvement . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Suggested Resources

National Parent Teacher Association (NPTA)— http://www.pta.org/ : This is the website of the National Parent Teacher Association (NPTA) that provides national information about Parent-Teacher Associations, information about the NPTA national convention, and resources. Information is also provided in Spanish.

Harvard Research Family Project— http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hfrp/about.html : This is the website of the Harvard Family Research Project, that helps philanthropies, policymakers, and practitioners develop strategies to promote the educational and social success and well-being of children, families, and their communities.

National Network of Partnership Schools (NNPS)— http://www.csos.jhu.edu/P2000/ : The National Network of Partnership Schools is a Johns Hopkins University organization that allows researchers, educators, parents, students, community members, and others to work together to enable all elementary, middle, and high schools develop and maintain effective programs of partnership.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Department of Human Development and Psychoeducational Studies, Howard University, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Velma LaPoint

Center for Urban Progress, Howard University, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Jo-Anne Manswell Butty

Prince George's County Public Schools, Prince George's County, Maryland, U.S.A.

Cheryl Danzy

Counseling and Psychological Services, University of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, U.S.A.

Charlynn Small

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology, The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers, U.S.A.

Caroline S. Clauss-Ehlers Ph.D. ( Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology ) ( Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

LaPoint, V., Butty, JA.M., Danzy, C., Small, C. (2010). Parental Involvement in Education. In: Clauss-Ehlers, C.S. (eds) Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71799-9_304

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71799-9_304

Published : 11 March 2015

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-71798-2

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-71799-9

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Effect of parental involvement on children’s academic achievement in chile.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Talca, Chile

- 2 Centro de Investigación sobre Procesos Socioeducativos, Familias y Comunidades, Núcleo Científico Tecnológico en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile

Parental involvement in school has been demonstrated to be a key factor for children’s academic outcomes. However, there is a lack of research in Chile, as well as in Latin American countries in general, leaving a gap in the literature about the generalization of findings outside developed and industrialized countries, where most of the research has been done. The present study aims to analyse the associations between parental involvement in school and children’s academic achievement. Cluster analysis results from a sample of 498 parents or guardians whose children attended second and third grades in 16 public elementary schools in Chile suggested the existence of three different profiles of parental involvement (high, medium, and low) considering different forms of parental involvement (at home, at school and through the invitations made by the children, the teachers, and the school). Results show that there are differences in children’s academic achievement between the parental involvement profiles, indicating children whose parents have a low involvement have lower academic achievement. Findings are in line with international research evidence, suggesting the need to focus on this variable too in Latin American contexts.

Introduction

On an international scale, parental involvement in school has long been heralded as an important and positive variable on children’s academic and socioemotional development. From an ecological framework, reciprocal positive interactions between these two key socializing spheres – families and schools – contribute positively to a child’s socioemotional and cognitive development ( Bronfenbrenner, 1987 ). Empirical findings have demonstrated a positive association between parental involvement in education and academic achievement ( Pérez Sánchez et al., 2013 ; Tárraga et al., 2017 ), improving children’s self-esteem and their academic performance ( Garbacz et al., 2017 ) as well as school retention and attendance ( Ross, 2016 ). Family involvement has also been found to be associated with positive school attachment on the part of children ( Alcalay et al., 2005 ) as well as positive school climates ( Cowan et al., 2012 ). Research has also evidenced that programs focused on increasing parental involvement in education have positive impacts on children, families, and school communities ( Jeynes, 2012 ; Catalano and Catalano, 2014 ).

Parent-school partnership allows for the conceptualization of roles and relationships and the impact on the development of children in a broader way ( Christenson and Reschly, 2010 ). From this approach, families and schools are the main actors in the construction of their roles and forms of involvement, generating new and varied actions to relate to each other according to the specific educational context. The main findings in the family-school field show a positive influence of this partnership, contributing to academic achievement and performance, among other positive consequences ( Epstein and Sander, 2000 ; Hotz and Pantano, 2015 ; Sebastian et al., 2017 ).

There is also strong support from international research showing the positive influence of parental involvement over academic achievement, as has been demonstrated in a variety of meta-analyses across different populations and educational levels ( Castro et al., 2015 ; Jeynes, 2016 ; Ma et al., 2016 ). Moreover, although there is a wide range of parental involvement definitions, some more general and others more specifics, there is a consensus among research results about the positive influence of parental involvement over child academic achievement. For example, in the meta-synthesis of Wilder (2014) , where nine meta-analyses are analyzed, this influence was consistent throughout the studies, regardless the different definitions and measures used.

However, most of the studies on parental involvement in education hail from anglophone countries and are based on cross-sectional and correlational designs ( Garbacz et al., 2017 ) while in Latin America research remains scarce. In a recent systematic review of the literature on parental involvement in education in Latin America, only one Mexican study from 1998 was found which was also heavily influenced by interventions from the United States ( Roth Eichin and Volante Beach, 2018 ). Chile has acknowledged the importance of collaborative relationships between families and schools developing a National Policy for Fathers, Mothers and Legal Guardians Participation in the Educational System (Política de Participación de Padres, Madres y Apoderados/as en el Sistema Educativo) in 2002 which was recently updated in 2017 ( Ministerio de Educación, Gobierno de Chile, 2017 ). Since the publication of this policy various local initiatives have sprouted in the country seeking to strengthen school family relations ( Saracostti-Schwartzman, 2013 ). Nevertheless, the majority of research in the country has thus far been of a qualitative nature with a focus on describing relations between family members and their schools, and identifying tensions between these two spheres ( Gubbins, 2011 ).

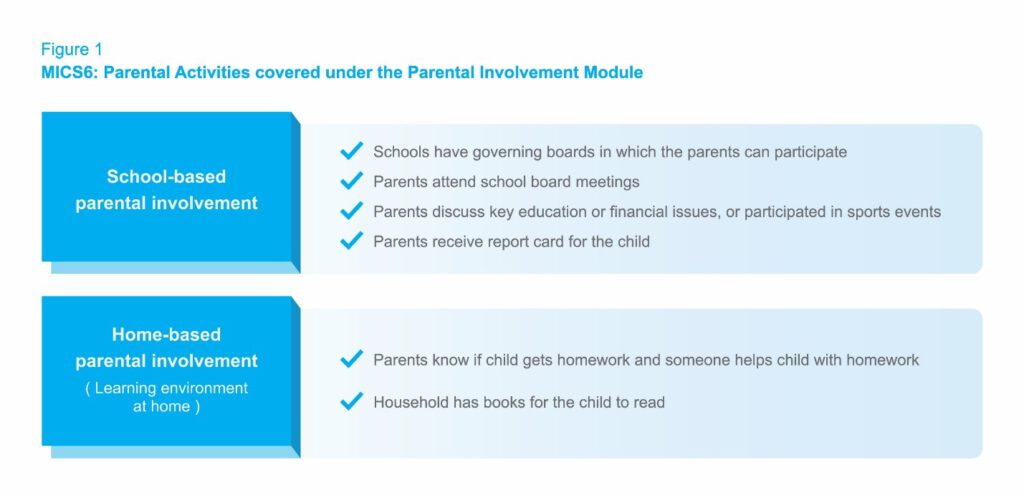

Thus, this study seeks to advance the analysis of the effects of parental involvement in school on the academic achievement of Chilean students. The study aims to analyse how different parental involvement profiles (based on the main forms of parental involvement identified in literature) influence children’s academic achieved. Parental involvement can take a wide variety of forms, among them, communication between family and school, supporting learning activities at home and involvement in school activities have been highlighted ( Schueler et al., 2017 ), these are included in this study using the scales proposed by Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (2005) .

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure.

The study included 498 parents or guardians whose children attended second and third grade in 16 public schools with high levels of socioeconomical vulnerability (over 85% according to official records of the schools) within three different regions in Chile (Libertador Bernando O’Higgins, Maule and Araucanía). Parents and guardians were aged between 20 and 89 years old ( M = 35.02, SD = 7.02 for parents, M = 59.27, SD = 11.74 for grandparents and M = 43.14, SD = 15.41 for other guardians) and students between 7 and 12 ( M = 8.30, SD = 0.93). The majority of them were mothers (83.9%). The majority of fathers and mothers had completed high school (33.1 and 40.6%, respectively), followed by elementary education (28.1 and 23.3%, respectively), no education completed (17.3% for both), professional title (7.2 and 6.8%, respectively) and university title (4.4 and 4.6%, respectively).

This study is part of a wider project focusing on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at strengthening the link between families and schools. This study has the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera and the Chilean National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (Acta 066-2017, Folio 036-17). Prior to data collection, after obtaining permission from the schools, informed consent forms were signed by the students’ legal guardians to authorize their participation. The data referring to the students (evaluation of learning outcomes) was compiled through official school records. The data referring to the families (parental involvement) was collected in paper format during parent teacher meetings at the end of the school year considering their behavior during the preceding year. Two research assistants trained for this purpose were present for the applications.

Instruments

Parental involvement was assessed using the five scales proposed by Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (2005) that aim to measure the level of family involvement in children’s education in elementary school from the point of view of the fathers, mothers and/or guardians. Scales have been adapted and validated by a panel of experts in Chile ( Reininger, 2014 ). Scales included in this study are: (1) Parental involvement activities at home [five items, such as “ someone in this family (father, mother and/or guardian) helps the child study for test” or “ someone in this family (father, mother and/or guardian) practices spelling, math or other skills with the child” ]; (2) Parental involvement activities at school (five items, such as “someone in this family attends parent–teacher association meetings ” or “ someone in this family attends special events at school ”), (3) Child invitations for involvement (five items, such us “ my child asks me to talk with his or her teacher ” or “ my child asks me to supervise his or her homework ”); (4) Teacher invitations for involvement (six items, such as “ my child’s teacher asks me to help out at school ” or “ my child’s teacher asks me to talk with my child about the school day ”); and (5) General school invitations for involvement (six items, such as “ this school staff contact me promptly about any problem involving my child ” or “ parents’ activities are scheduled at this school so that we can attend ”). The first four scales have a four-point Likert response scale, that indicate the frequency of the items, from 0 ( never ) to 3 ( always ). The last scale has a 5-point Likert scale response, indicating the grade of agreement with the items, from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 5 ( strongly agree ). Scales can be consulted as Supplementary Tables 1–5 . Internal consistency of all scales was adequate (α = 0.79, α = 0.72, α = 0.72, α = 0.85, and α = 0.87, respectively).

Students’ academic achievement was evaluated thought the final average grade obtained at the end of the school year, recorded in a scale from 1 ( minimum achievement ) to 7 ( maximum achievement ).

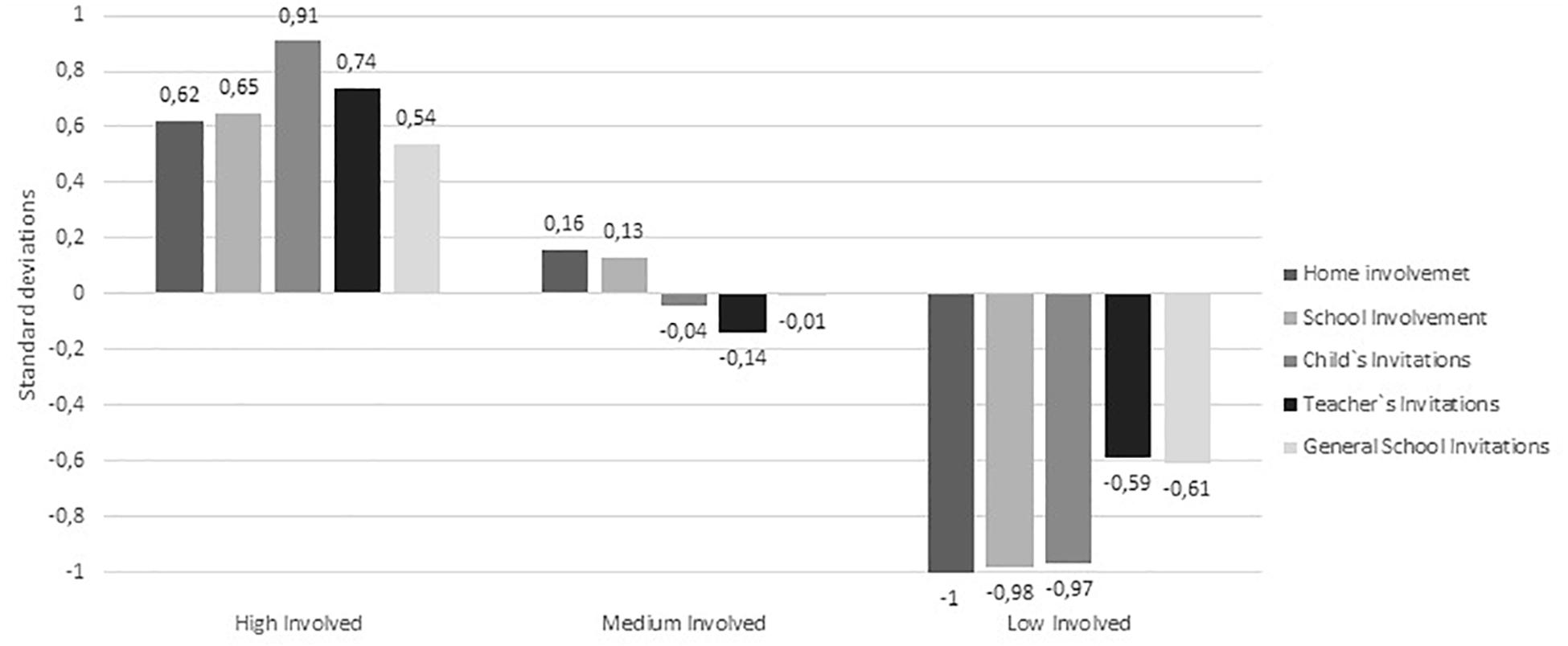

Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to identify parental involvement profiles based on the five subscales of parental involvement scale (typified to avoid the influence of the different scale responses), applying the standardized Euclidian Distance method and using Ward’s algorithm. Cluster analyses results showed that the optimal solution was the grouping of the participants into three groups. In Figure 1 the typified scores of each of the variables considered to calculate the groups are shown.

Figure 1. Parental involvement profiles.

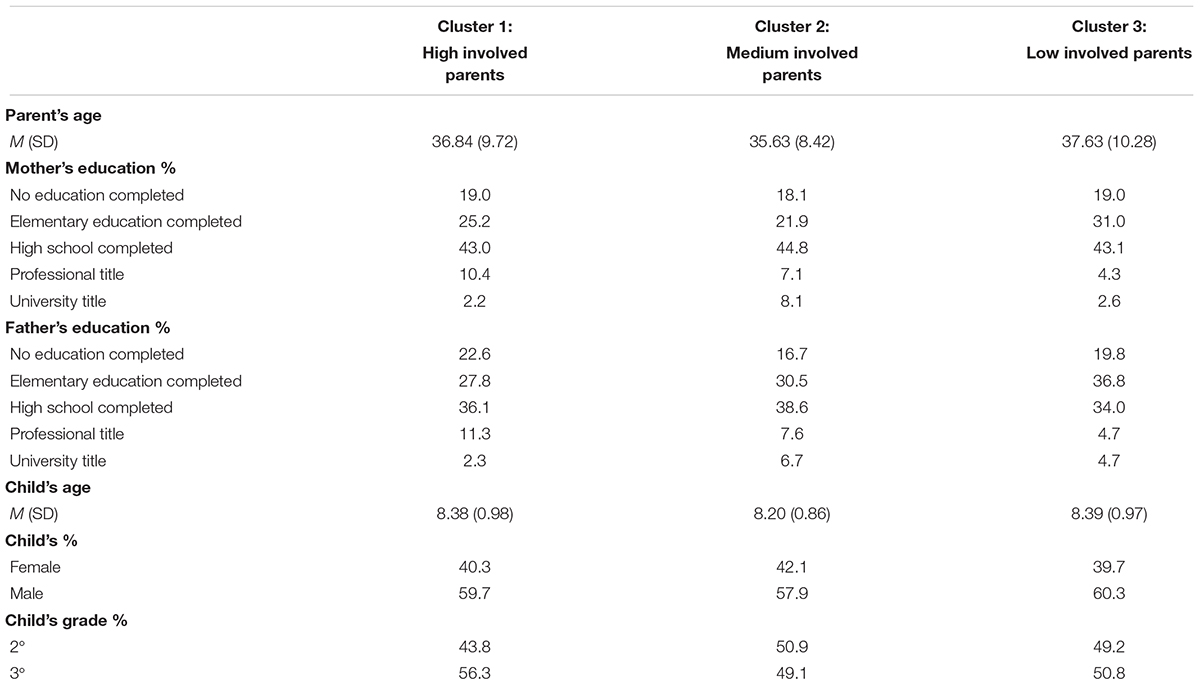

To label the groups, we examined the family involvement profiles by computing a one-way ANOVA on the standardized scores of the five parental involvement scales with the clusters serving as the factors. The result revealed that the clustering variables significantly differed between the involvement scales [Parental involvement at home: F (2,497) = 147.83, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.37; Parental involvement at school: F (2,497) = 148.82, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.38; Child invitation for involvement: F (2,497) = 225.34, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.48; Teacher invitation for involvement: F (2,497) = 84.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.26; General school Invitation for involvement: F (2,497) = 53.38, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.18]. Scheffe post hoc multiple comparisons showed the differences were statistically significant between all the parental involvement profiles in all variables, with the first cluster scoring higher than the second and the third in all the scales, and the second higher that the third. Based on these differences and the scores, the first cluster was labeled as High involved parents , representing 144 parents (28.9%) that scored above the mean in all the involvement scales (from 0.54 to 0.91 standards deviations). The second cluster was named Medium involved parent s, including 228 parents (45.8%) that have scores close to the media in all the involvement scales (from -0.14 to 0.16 standards deviations). Finally, the third cluster was classified as Low involved parents , including 126 parents (25.3%) that scored below the mean in all the involvement scales (from -0.61 to -0.91 standards deviations). Table 1 shows demographic information for the clusters.

Table 1. Demographic information of the clusters.

Finally, ANOVA results showed that there were significant differences in academic achievement scores between the three clusters of parent involvement profiles, F (2,430) = 5.37, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.03. Scheffe post hoc multiple comparisons showed that high ( M = 5.97, SD = 0.49) and medium ( M = 6.00, SD = 0.50) involved parents had children with higher academic achievement than low involved parents ( M = 5.8, SD = 0.47). Complementarily, results from correlations between parental involvement and academic achievement scores support these results, showing a significant and positive correlation( r = 0.14, p = 0.003).

From the results presented, we can conclude the existence of three different profiles of parental involvement (high, medium and low) considering different scales of parental involvement (at home, at school and through the invitations made by the children, the teachers and the school). Secondly, results showed that there were differences in academic achievement scores between the parent involvement profiles, where high and medium involved parents had children with higher academic achievement than low involved parents.

As shown, international literature reveals that the degree of parental involvement is a critical element in the academic achievements of children, especially during their first school years highlighting the need to generate scientific evidence from the Chilean context. Most of the studies in this area come from anglophone countries ( Garbacz et al., 2017 ) while in the Latin American context research is still scarce. Results from our study corroborate that parental involvement can contribute alike in other cultural contexts, pointing to the need to also implement policies to promote it.

In this context, Chile has acknowledged the importance of collaborative relationships between parents and schools leading to the development a National Policy for Father, Mother and Legal Guardian Participation. Nevertheless, most of the research in the country has thus far been of a qualitative nature with a focus on describing family-school relations and identifying tensions between these two spheres ( Gubbins, 2011 ). Thus, this study seeks to make progress in the analysis of the effect of parental involvement and children’s and academic achievements of Chilean students.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Chilean National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera and the Chilean National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research.

Author Contributions

MS developed the study concept and the study design. LL substantially contributed to the study concept, and performed the data analysis and interpretation. MS and LL drafted the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. They also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This work was supported by FONDECYT 1170078 of the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research of Chile.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01464/full#supplementary-material .

Alcalay, L., Milicic, N., and Toretti, A. (2005). Alianza efectiva familia-escuela: un programa audiovisual para padres. Psychke 14, 149–161. doi: 10.4067/S0718-22282005000200012

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1987). La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica.

Google Scholar

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., and Gaviria, J. J. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Catalano, H., and Catalano, C. (2014). The importance of the school-family relationship in the child’s intellectual and social development. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 128, 406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.179

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Christenson, S. L., and Reschly, A. L. (2010). Handbook of School-Family Partnerships. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cowan, G., Bobby, K., St. Roseman, P., and Echandia, A. (2012). Evaluation Report: The Home Visit Project. ERIC database No. ED466018.

Epstein, J. L., and Sander, M. (2000). Handbook of the Sociologic of Education. New York, NY: Springer.

Garbacz, S. A., Herman, K. C., Thompson, A. M., and Reinke, W. M. (2017). Family engagement in education and intervention: implementation and evaluation to maximize family, school, and student outcomes. J. Sch. Psychol. 62, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.04.002

Gubbins, V. (2011). Estrategias de Involucramiento Parental de Estudiantes con Buen Rendimiento Escolar en Educación Básica. Doctoral dissertation, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago.

Hoover-Dempsey, K., and Sandler, H. (2005). The Social Context of Parental Involvement: A Path to Enhanced Achievement. Final Report OERI/IES grant No. R305T010673. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

Hotz, V. J., and Pantano, J. (2015). Strategic parenting, birth order, and school performance. J. Popul. Econ. 28, 911–936. doi: 10.1007/s00148-015-0542-3

Jeynes, W. H. (2012). A Meta-Analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Educ. 47, 706–742. doi: 10.1177/0042085912445643

Jeynes, W. H. (2016). A Meta-Analysis: the relationship between parental involvement and Latino student outcomes. Educ. Urban Soc. 49, 4–28. doi: 10.1177/0013124516630596

Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Hu, S., and Yuan, J. (2016). A Meta-Analysis of the relationship between learning outcomes and parental involvement during early childhood education and early elementary education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 771–801. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1

Ministerio de Educación, Gobierno de Chile (2017). Política de Participación de las Familias y la Comunidaden las Instituciones Educativas. Available at: http://basica.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2017/04/Pol%C3%ADtica-de-Participaci%C3%B3n-de-la-Familia-y-la-Comunidad-en-instituciones-educativas.pdf

Pérez Sánchez, C. N., Betancort Montesinos, M., and Cabrera Rodríguez, L. (2013). Family influences in academic achievement: a study of the Canary Islands. Rev. Int. Sociol. 71, 169–187. doi: 10.3989/ris.2011.04.11

Reininger, T. (2014). Parental Involvement in Municipal Schools in Chile: Why do Parents Choose to get Involved? Ph.D. dissertation, Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service, New York, NY.

Ross, T. (2016). The differential effects of parental involvement on high school completion and postsecondary attendance. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 24, 1–38. doi: 10.14507/epaa.v24.2030

Roth Eichin, N., and Volante Beach, P. (2018). Liderando alianzas entre escuelas, familias y comunidades: una revisión sistemática. Rev. Complut. Educ. 29, 595–611. doi: 10.5209/RCED.53526

Saracostti-Schwartzman, M. (2013). Familia, Escuela y Comunidad I: Una Alianza Necesaria Para un Modelo de Intervención biopsicosocial Positive. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria.

Schueler, B. E., McIntyre, J. C., and Gehlbach, H. (2017). Measuring parent perceptions of family–school engagement: the development of new survey tools. Sch. Commun. J. 27, 275–301.

Sebastian, J., Moon, J.-M., and Cunningham, M. (2017). The Relationship of school-based parental involvement with student achievement: a comparison of principal and parent survey reports from PISA 2012. Educ. Stud. 43, 123–146. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2016.1248900

Tárraga, V., García, B., and Reyes, J. (2017). Home-based family involvement and academic achievement: a case study in primary education. Educ. Stud. 44, 361–375. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2017.1373636

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: a meta-synthesis. Educ. Rev. 66, 377–397. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

Keywords : parental involvement profiles, children’s academic achievement, elementary education, family and school relations, child development

Citation: Lara L and Saracostti M (2019) Effect of Parental Involvement on Children’s Academic Achievement in Chile. Front. Psychol. 10:1464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01464

Received: 29 January 2019; Accepted: 11 June 2019; Published: 27 June 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Lara and Saracostti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Lara, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Financial Information

- Our History

- Our Leadership

- The Casey Philanthropies

- Workforce Composition

- Child Welfare

- Community Change

- Economic Opportunity

- Equity and Inclusion

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Impact Investments

- Juvenile Justice

- KIDS COUNT and Policy Reform

- Leadership Development

- Research and Evidence

- Child Poverty

- Foster Care

- Juvenile Probation

- Kinship Care

- Racial Equity and Inclusion

- Two-Generation Approaches

- See All Other Topics

- Publications

- KIDS COUNT Data Book

- KIDS COUNT Data Center

Parental Involvement in Your Child’s Education

The key to student success, research shows.

If you could wave a magic wand that would improve the chances of school success for your children as well as their classmates, would you take up that challenge?

For decades, researchers have pointed to one key success factor that transcends nearly all others, such as socioeconomic status, student background or the kind of school a student attends: parental involvement.

The extent to which schools nurture positive relationships with families — and vice versa — makes all the difference, research shows. Students whose parents stay involved in school have better attendance and behavior, get better grades, demonstrate better social skills and adapt better to school.

Parental involvement also more securely sets these students up to develop a lifelong love of learning , which researchers say is key to long-term success.

A generation ago, the National PTA found that three key parent behaviors are the most accurate predictors of student achievement, transcending both family income and social status:

- creating a home environment that encourages learning;

- communicating high, yet reasonable, expectations for achievement; and

- staying involved in a child’s education at school.

What’s more, researchers say when this happens, the motivation, behavior and academic performance of all children at a particular school improve. Simply put, the better the partnership between school and home, the better the school and the higher the student achievement across the board.

Download Our Parental Involvement in Education Report

What Is Parental Involvement, and How Is It Different From Parental Engagement?

Parental involvement is the active, ongoing participation of a parent or primary caregiver in the education of a child. Parents can demonstrate involvement at home by:

- reading with children;

- helping with homework;

- discussing school events;

- attending school functions, including parent-teacher meetings; and

- volunteering in classrooms.

While both parental involvement and parental engagement in school support student success, they have important differences.

Involvement is the first step towards engagement. It includes participation in school events or activities, with teachers providing learning resources and information about their student’s grades. With involvement, teachers hold the primary responsibility to set educational goals.

But while teachers can offer advice, families and caregivers have important information about their children that teachers may not know. So a student’s learning experience is enriched when both bring their perspectives to the table.

With engagement , home and school come together as a team. Schools empower parents and caregivers by providing them with ways to actively participate, promoting them as important voices in the school and removing barriers to engagement. Examples include encouraging families to join the family-teacher association or arranging virtual family-teacher meetings for families with transportation issues.

Research has found that the earlier educators establish family engagement, the more effective they are in raising student performance.

Why Is It Important to Involve Parents in School?

It benefits students.

Children whose families are engaged in their education are more likely to:

- earn higher grades and score higher on tests;

- graduate from high school and college;

- develop self-confidence and motivation in the classroom; and

- have better social skills and classroom behavior.

In one study, researchers looked at longitudinal data on math achievement and found that effectively encouraging families to support students’ math learning at home was associated with higher percentages of students who scored at or above proficiency on standardized math achievement tests.

Students whose parents are involved in school are also less likely to suffer from low self-esteem or develop behavioral issues, researchers say.

And classrooms with engaged families perform better as a whole, meaning that the benefits affect virtually all students in a classroom.

It Positively Influences Children’s Behavior

Decades of research have made one thing clear: parental involvement in education improves student attendance, social skills and behavior. It also helps children adapt better to school.

In one instance, researchers looking at children’s academic and social development across first, third and fifth grade found that improvements in parental involvement are associated with fewer “ problem behaviors” in students and improvements in social skills. Researchers also found that children with highly involved parents had “ enhanced social functioning” and fewer behavior problems.

It Benefits Teachers

Because it improves classroom culture and conditions, parent involvement also benefits teachers. Knowing more about a student helps teachers prepare better and knowing that they have parents’ support ensures that teachers feel equipped to take academic risks and push for students to learn more.

How Can Parents Get Involved in Their Child’s Education?

- Make learning a priority in your home, establishing routines and schedules that enable children to complete homework, read independently, get enough sleep and have opportunities to get help from you. Talk about what’s going on in school.

- Read to and with your children: Even 10 – 20 minutes daily makes a difference. And parents can go further by ensuring that they read more each day as well, either as a family or private reading time that sets a good example.

- Ask teachers how they would like to communicate. Many are comfortable with text messages or phone calls, and all teachers want parents to stay up to date, especially if problems arise.

- Attend school events, including parent-teacher conferences, back-to-school nights and others — even if your child is not involved in extracurricular activities.

- Use your commute to connect with your kids; ask them to read to you while you drive and encourage conversations about school.

- Eat meals together: It’s the perfect opportunity to find out more about what’s going on in school.

- Prioritize communication with teachers, especially if demanding work schedules, cultural or language barriers are an issue. Find out what resources are available to help get parents involved.

Parental Involvement Outside the Classroom

Outside of the classroom, engaged parents more often see themselves as advocates for their child’s school — and are more likely to volunteer or take an active role in governance.

Researchers have noted that parent involvement in school governance, for instance, helps parents understand educators’ and other parents’ motivations, attitudes and abilities. It gives them a greater opportunity to serve as resources for their children, often increasing their own skills and confidence. In a few cases, these parents actually further their own education and upgrade their job.

While providing improved role models for their children, these parents also ensure that the larger community views the school positively and supports it. They also provide role models for future parent leaders.

Reading and Homework

Very early in their school career — by fourth grade — children are expected to be able to read to learn other subjects. But recent research shows that about two-thirds of the nation’s public school fourth graders aren’t proficient readers .

To make children successful in reading , and in school more generally, the single most important thing you can do is to read aloud with them.

Youth Sports and Other Extracurricular Activities

Parents can make or break their child’s relationship with sports and other extracurricular activities, so they should think deeply about how to show children the fun of mastering a new skill, working toward a group or individual goal, weathering adversity, being a good sport and winning or losing gracefully.

Beyond this, parents with coaching skills should consider volunteering to get involved. The National Alliance for Youth Sports notes that only about 5 % to 10 % of youth sports coaches have received any relevant training before coaching, with most coaches stepping up because their child is on the team and no one else volunteered.

Parental Involvement in Juvenile Justice

Parents finding themselves involved in the juvenile justice system on behalf of their kids face a system that offers many challenges and few resources.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative has long sought to sharply reduce reliance on detention, with the aim of decreasing reliance on juvenile incarceration nationwide.

But parents whose children face the judicial system can make a difference. Surveys of corrections officials note that family involvement is one of the most important issues facing the juvenile system, and it is also the most operationally challenging.

One well-respected framework outlines the importance of five “ dimensions” that measure parental involvement, including receptivity to receiving help, a belief in positive change, investment in planning and obtaining services and a good working relationship between the parent and the justice system.

What Successful Parental Involvement Looks Like

Experts urge parents to be present at school as much as possible and to show interest in children’s schoolwork.

As noted in the Annie E. Casey Foundation “ Parental Involvement in Education Policy” brief, the National PTA lists six key standards for good parent/family involvement programs:

- Schools engage in regular, two-way, meaningful communication with parents.

- Parenting skills are promoted and supported.

- Parents play an integral role in assisting student learning.

- Parents are welcome in the school as volunteers, and their support and assistance are sought.

- Parents are full partners in the decisions that affect children and families.

- Community resources are used to strengthen schools, families and student learning.

How To Avoid Negative Parental Involvement

Teachers may, on occasion, complain of “ helicopter parents” whose involvement — sometimes called “ hovering” — does more harm than good. One veteran educator recently told the story of an award-winning colleague who quit the profession because of the growing influence of “ a group of usually well-intentioned, but over-involved, overprotective and controlling parents who bubble-wrap their children.”

What these parents fail to understand, he said, is that their good intentions “ often backfire,” impeding their children’s coping skills and capacity to problem-solve. Such over-involvement can actually increase children’s anxiety and reduce self-esteem.

The colleague’s plea: “ Please partner with us rather than persecute us. That will always be in your children’s best interests.”

Resources for Parents, Teachers, School Administrators and Advocates

- Child Trends Families and Parenting Research

- Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Usable Knowledge series

- Parent Institute for Quality Education

- The National Parent Teacher Association

- Johns Hopkins University National Network of Partnership Schools

- The Casey Foundation Parental Involvement in Education policy brief

- The Casey Foundation’s Families as Primary Partners in Their Child’s Development and School Readiness

This post is related to:

Popular posts.

View all blog posts | Browse Topics

blog | January 12, 2021

What Are the Core Characteristics of Generation Z?

blog | June 3, 2021

Defining LGBTQ Terms and Concepts

blog | August 1, 2022

Child Well-Being in Single-Parent Families

Subscribe to our newsletter to get our data, reports and news in your inbox.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Parent involvement and student academic performance: A multiple mediational analysis

David r. topor.

a The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University/Bradley Hospital, 1011 Veterans Memorial Parkway, East Providence, RI 02915

Susan P. Keane

b The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Psychology, P.O. Box 26170, Greensboro, NC 27402-6164

Terri L. Shelton

Susan d. calkins.

Parent involvement in a child's education is consistently found to be positively associated with a child's academic performance. However, there has been little investigation of the mechanisms that explain this association. The present study examines two potential mechanisms of this association: the child's perception of cognitive competence and the quality of the student-teacher relationship. This study used a sample of 158 seven-year old participants, their mothers, and their teachers. Results indicated a statistically significant association between parent involvement and a child's academic performance, over and above the impact of the child's intelligence. A multiple mediation model indicated that the child's perception of cognitive competence fully mediated the relation between parent involvement and the child's performance on a standardized achievement test. The quality of the student-teacher relationship fully mediated the relation between parent involvement and teacher ratings of the child's classroom academic performance. Limitations, future research directions, and implications for public policy initiatives were discussed.

Parent involvement in a child's early education is consistently found to be positively associated with a child's academic performance ( Hara & Burke, 1998 ; Hill & Craft, 2003 ; Marcon, 1999 ; Stevenson & Baker, 1987 ). Specifically, children whose parents are more involved in their education have higher levels of academic performance than children whose parents are involved to a lesser degree. The influence of parent involvement on academic success has not only been noted among researchers, but also among policy makers who have integrated efforts aimed at increasing parent involvement into broader educational policy initiatives. Coupled with these findings of the importance of early academic success, a child's academic success has been found to be relatively stable after early elementary school ( Entwisle & Hayduk, 1988 ; Pedersen, Faucher, & Eaton, 1978 ). Therefore, it is important to examine factors that contribute to early academic success and that are amenable to change.

Researchers have reported that parent-child interactions, specifically stimulating and responsive parenting practices, are important influences on a child's academic development ( Christian, Morrison, & Bryant, 1998 ; Committee on Early Childhood Pedagogy, 2000 ). By examining specific parenting practices that are amenable to change, such as parent involvement, and the mechanisms by which these practices influence academic performance, programs may be developed to increase a child's academic performance. While parent involvement has been found to be related to increased academic performance, the specific mechanisms through which parent involvement exerts its influence on a child's academic performance are not yet fully understood ( Hill & Craft, 2003 ). Understanding these mechanisms would inform further research and policy initiatives and may lead to the development of more effective intervention programs designed to increase children's academic performance.

Models of Parent Involvement

Parent involvement has been defined and measured in multiple ways, including activities that parents engage in at home and at school and positive attitudes parents have towards their child's education, school, and teacher ( Epstein, 1996 ; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994 ; Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000 ). The distinction between the activities parents partake in and the attitude parents have towards education was highlighted by several recent studies. Several studies found that increased frequency of activities was associated with higher levels of child misbehavior in the classroom ( Izzo, Weissberg, Kasprow, & Fendrich, 1999 ), whereas positive attitudes towards education and school were associated with the child's increased academic performance ( Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, Cox, & Bradley, 2003 ). Specifically, Izzo et al. (1999) reported that an increase in the parent's school activities, such as increased number of parent-teacher contacts, was associated with worsening achievement, as increased contacts may have occurred to help the teacher manage the child's existing behavior problems. The significance of parent attitudes toward education and school is less well understood, although attitudes are believed to comprise a key dimension of the relationship between parents and school (Eccles & Harold, 1996). Parents convey attitudes about education to their children during out-of-school hours and these attitudes are reflected in the child's classroom behavior and in the teacher's relationship with the child and the parents ( Kellaghan, Sloane, Alvarez, & Bloom, 1993 ).

Assessment of Academic Performance in Early Elementary School

Several methods are used to measure child academic performance, including standardized achievement test scores, teacher ratings of academic performance, and report card grades. Standardized achievement tests are objective instruments that assess skills and abilities children learn through direct instruction in a variety of subject areas including reading, mathematics, and writing ( Sattler, 2001 ). Teacher rating scales allow teachers to rate the accuracy of the child's academic work compared to other children in the class, and allow for ratings on a wider range of academic tasks than examined on standardized achievement tests ( DuPaul & Rapport, 1991 ). Report card grades allow teachers to report on classroom academic performance, but are used by few studies for early elementary school children due to, among other reasons, a lack of a standardized grading system and uniform subject areas children are evaluated on.

Proposed Explanations of the Relation Between Parent Involvement and Academic Performance

Based on previous research, it was hypothesized that parents who have a positive attitude towards their child's education, school, and teacher are able to positively influence their child's academic performance by two mechanisms: (a) by being engaged with the child to increase the child's self-perception of cognitive competence and (b) by being engaged with the teacher and school to promote a stronger and more positive student-teacher relationship.

Perceived Cognitive Competence

Perceived cognitive competence is defined as the extent to which children believe that they possess the necessary cognitive skills to be successful when completing academic tasks, such as reading, writing, and arithmetic ( Harter & Pike, 1984 ). Previous research found evidence that higher parent involvement contributes to an increase in a child's perceived level of competence ( Gonzalez-DeHass, Willems, & Holbein, 2005 ; Grolnick, Ryan, & Deci, 1991 ). There are theoretical pathways through which children's perceptions and expectations of their cognitive competence are influenced by others: (a) performance accomplishments/performance mastery, (b) vicarious reinforcement, (c) verbal persuasion, and (d) emotion regulation ( Bandura, 1977 ). In addition, a child's increased perception of cognitive competence is consistently related to higher academic performance ( Chapman, Skinner, & Baltes, 1990 ; Ladd & Price, 1986 ; Schunk, 1981 ). Based on theory and previous findings, Gonzalez-DeHass et al., (2005) suggest that perceived cognitive competence be examined to explain the relation between parent involvement and a child's academic performance.

The Student-Teacher Relationship

A positive student-teacher relationship has been defined as the teacher's perception that his or her relationship with the child is characterized by closeness and a lack of dependency and conflict ( Birch & Ladd, 1997 ). Closeness is the degree of warmth and open communication between the student and teacher, dependency is the over-reliance on the teacher as a source of support, and conflict is the degree of friction in student-teacher interactions ( Birch & Ladd, 1997 ). Previous research found that close, positive student-teacher relationships are positively related to a wide range of child social and academic outcomes in school ( Hughes, Gleason, & Zhang, 2005 ). Specifically, a close student-teacher relationship is an important predictor of a child's academic performance ( Birch & Ladd, 1997 ; Hamre & Pianta, 2001 ). Previous research has also found that parent involvement in a child's education positively influences the nature of the student-teacher relationship ( Hill & Craft, 2003 ; Stevenson & Baker, 1987 ). Therefore, the student-teacher relationship was examined for its ability to explain the relation between parent involvement and a child's academic performance.

The Present Study

Parent involvement is one factor that has been consistently related to a child's increased academic performance ( Hara & Burke, 1998 ; Hill & Craft, 2003 ; Marcon, 1999 ; Stevenson & Baker, 1987 ). While this relation between parent involvement and a child's academic performance is well established, studies have yet to examine how parent involvement increases a child's academic performance. The goal of the present study was to test two variables that may mediate, or explain how, parent involvement is related to a child's academic performance. Parent involvement was defined as the teacher's perception of “the positive attitude parents have towards their child's education, teacher, and school” ( Webster-Stratton, 1998 ). Academic performance was measured by two methods: standardized achievement test scores and teacher report of academic performance through rating scales. Based on previous research ( Gonzalez-DeHass et al., 2005 ; Hughes et al., 2005 ), two possible mechanisms, a child's perception of cognitive competence as measured by the child's report, and the student-teacher relationship as measured by the teacher's report, were examined for their ability to mediate the relation between parent involvement and academic performance. It was predicted that parent involvement would no longer be a significant predictor of a child's academic performance when the child's cognitive competence and the student-teacher relationship were accounted for in the analyses.

Participants

Participants in this cross-sectional study were one hundred and fifty-eight (158) children who, at age seven, participated in the laboratory and school visits. Participants were obtained from three different cohorts participating in a larger ongoing longitudinal study. 447 participants were initially recruited at two years of age through child care centers, the County Health Department, and the local Women, Infants, and Children program. Consistent with the original longitudinal sample ( Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos, & Shelton, 2004 ), 66.5% of the children ( N = 105) were European American, 26.6% of the children were African American ( N = 42), seven children (4.4%) were bi-racial, and four children (2.5%) were of another ethnic background. Seventy-one (45%) of the participants were male and 87 (55%) were female. Socioeconomic status ranged from lower to upper class as measured by the family's Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status score ( Hollingshead, 1975 ).

Parent Involvement

The teacher version of the Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire (INVOLVE) was used to assess parent involvement. The measure is a twenty-item scale with a 5-point scale answer format ( Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001 ). The “Parent Involvement in Education” subscale includes six items and assesses the teacher's perception of the positive attitude parents have towards their child's education, teacher, and school. Examples of these items include “How much is this parent interested in getting to know you?’ and “How important is education in this family?”

Student-Teacher Relationship

The Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS) consists of 28 items that measure aspects of the relationship between the student and teacher ( Pianta, 2001 ). Item responses are in a 5-point Likert-style format. Items assess the teacher's feelings about a child, the teacher's beliefs about the child's feelings towards the teacher, and the teacher's observation of the child's behavior in relation to the teacher ( Pianta & Nimetz, 1991 ). The measure yields three subscales: “Conflict,” “Closeness,” “Dependency”. An overall “Positive Student-Teacher Relationship Scale” is calculated by summing the items on the “Closeness” scale and the reverse-score of the items on the “Conflict” and “Dependency” scales. Examples of items include “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child” (Closeness), “This child easily becomes angry with me” (Conflict), and “This child is overly dependent on me” (Dependency).

Perceived Competence

The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children ( Harter & Pike, 1984 ) consists of 24 items that measure four domains of self-concept: (a) perceived cognitive competence, (b) perceived physical competence, (c) peer social acceptance, and (d) maternal social acceptance. Children are shown pictures of a child who is successful at completing a task and one who is unsuccessful, and are asked to choose the picture most similar to them. Items include a child naming alphabet letters or running in a race. This study used the mean of the six items on the perceived cognitive competence subscale. Previous research has used this subscale as a stand-alone measure in analyses ( Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994 ).

Academic Performance

Two measures of academic performance were used. The Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Second Edition (WIAT-II; The Psychological Corporation, 2002 ) is an individually administered, nationally standardized measure of academic achievement ( Sattler, 2001 ). Children were administered the five subtests comprising the Reading and Mathematics composites. As the current study was interested in examining a more global standardized measure of academic achievement, and since the Reading and Mathematics composites were related ( r = .60, p <.001), the mean of the combined Reading and Mathematics composites was used as the child's standardized achievement test score.

The Academic Performance Rating Scale (APRS) ( DuPaul & Rapport, 1991 ) is a 19-item scale, where teachers rate the child's academic abilities and behaviors in the classroom on a 5-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater classroom academic performance. As the current study focused on academic performance and not other behaviors, only two items on the APRS that corresponded to the child's actual classroom academic performance were examined: “accuracy of the child's completed written math work” and “accuracy of the child's written language arts work”. These two items were highly correlated ( r = .84, p <.001). A mean of the items was used as the measure of classroom academic performance.

Intelligence

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition (WISC-III) is a nationally standardized and individually administered measure of general intelligence for children aged 6-16 years ( Wechsler, 1991 ). The WISC-III provides three IQ scores (Verbal, Performance, and Full Scale), each with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15. The current study used the child's Full Scale IQ score.

Data were gathered from the child and the child's mother during two visits to the laboratory and from the child's teacher during one visit to the child's school. The child's IQ, academic achievement, and perceived cognitive competence were assessed in a one-on-one session with a trained graduate student clinician during the two laboratory visits, when the child was seven years old. The child's mother provided updated demographic information. School visits began several months into the school year to allow teachers adequate time to become familiar with the child and the child's mother. Teachers completed a packet of questionnaires, including a measure on parent involvement and the child's classroom academic performance.

Mediation Analysis

A mediator is defined as a variable that allows researchers to understand the mechanism through which a predictor influences an outcome by establishing “how” or “why” an independent variable predicts an outcome variable ( Baron & Kenny, 1986 ). In the current study, the independent variable was parent involvement and the two dependent variables were a child's standardized achievement test score and classroom academic performance. The two potential mediators were the child's perception of cognitive competence and the quality of the student-teacher relationship. Four regression analyses were performed to test each potential mediator and variables considered as co-variates were controlled for in all regression equations. A multiple mediation model was used to examine if both potential mediators jointly reduce the direct effect of parent involvement on a child's academic performance and to better understand the unique contribution of each individual mediator when the other mediator is controlled for ( Preacher & Hayes, 2006 ). Baron and Kenny (1986) state that to test a mediator the first regression must show that the independent variable affects the mediator, the second that the independent variable affects the dependent variable, and the third that the mediator affects the dependent variable. For full multiple mediation, the fourth regression must show that after controlling for the mediators (child's perception of cognitive competence and student-teacher relationship), the independent variable (parent involvement) no longer significantly predicts the dependent variable (standardized achievement test score/classroom academic performance). Partial mediation exists if the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is reduced, but still significant, when the mediators are controlled ( Baron & Kenny, 1986 ).

The mediation was also tested by using the Sobel (1982) test to examine the reduction of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, after accounting for the mediating variables. The Sobel (1982) test conservatively tests this reduction by dividing the effect of the mediator by its standard error and then comparing this term to a standard normal distribution to test for significance ( MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002 ).

The Cronbach's alpha for the six items on the INVOLVE-T “Parent Involvement in Education” subscale was α = .91, indicating good internal consistency. The reliability of the 28 items on the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale “Positive Student-Teacher Relationship Scale” and the six items on the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children cognitive competence subscale was adequate (Cronbach's alpha α = .86 and .80, respectively).

Bivariate correlations between the variables of interest and demographic variables are presented in Table 1 . The child's Full-Scale IQ score was significantly related to the child's WIAT-II score ( r = .68, p <. 001), to the child's classroom academic performance ( r = .47, p <. 001), and to parent involvement ( r = .39, p < .001). Given these significant findings, the child's Full-Scale IQ score was used as a control variable in the regression analyses addressing the research questions. As shown in Table 1 , significant positive correlations existed between parent involvement and the student-teacher relationship ( r = .48, p < .001), the child's perception of cognitive competence ( r = .31, p < .001), the child's WIAT-II score ( r = .43, p < .001), and the child's classroom academic performance ( r = .35, p < .001).

Correlations Between Variables of Interest

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Socioeconomic Status (Hollingshead) | - | ||||||

| 2. Full Scale IQ Score (WISC-III) | .42 | - | |||||

| 3. Parent Involvement (INVOLVE-T) | .26 | .39 | - | ||||

| 4. Perceived Cognitive Competence (Harter) | .17 | .34 | .31 | - | |||

| 5. Positive Student-Teacher Relationship (STRS) | .04 | .20 | .48 | .20 | - | ||

| 6. Standardized Achievement Test Score (WIAT-II) | .31 | .68 | .43 | .54 | .26 | - | |

| 7. Classroom Academic Performance (APRS) | .24 | .47 | .35 | .24 | .38 | .46 | - |

It was hypothesized that parent involvement would predict academic performance, as measured by both the WIAT-II achievement score and teacher ratings of a child's classroom academic performance. As shown in Table 2 , parent involvement was a significant predictor of the child's WIAT-II score F (3, 154) change = 9.88, p < .01, β = .20, over and above the variance accounted for by the child's IQ. Parent involvement was a significant predictor of the child's classroom academic performance, F (3, 154) change = 6.68, p < .05, β = .20, over and above the variance accounted for by the child's IQ. It was hypothesized that parent involvement would predict the child's perception of cognitive competence and the quality of the student-teacher relationship. As expected, parent involvement was a significant predictor of a child's perception of cognitive competence ( β = .21, p < .01) and a positive student-teacher relationship ( β = .47, p < .001), after controlling for IQ. Next, the two mediators (perceived cognitive competence and a positive student-teacher relationship) were independently tested as predictors of the two measures of academic performance. After controlling for IQ, perceived cognitive competence was a significant predictor of a child's WIAT-II score ( β = .35, p < .001), but not a significant predictor of the child's classroom academic performance ( β = .09, p = .23). After controlling for IQ, a positive student-teacher relationship positively predicted a child's WIAT-II score ( β = .13, p < .05) and a child's classroom academic performance ( β = .30, p < .001).

Regression Analyses Testing Parent Involvement as a Predictor of Child Academic Performance

| B | SE B | β | R | R Change | F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Examining Parent Involvement as a Predictor of Child's WIAT-II Score | ||||||

| Step 1. Full Scale IQ | .54 | .06 | .52 | .46 | .46 | 134.93 |

| Step 2. Parent Involvement | 3.38 | 1.08 | .20 | .50 | .04 | 9.88 |

| Regression Examining Parent Involvement as a Predictor of the Student-Teacher Relationship | ||||||

| Step 1. Full Scale IQ | .03 | .01 | .39 | .22 | .22 | 44.19 |

| Step 2. Parent Involvement | .24 | .09 | .20 | .26 | .04 | 6.68 |

Finally, the mediational model was tested by examining whether parent involvement continued to have a significant effect on the measures of academic performance, after controlling for the mediators and for the child's IQ. As shown in Table 3 , parent involvement was no longer a significant predictor of a child's WIAT-II score when the child's cognitive competence and the student-teacher relationship were accounted for in the analyses (β = .11, p = .08). The multiple mediation analysis indicated that only perceived cognitive competence uniquely predicted the child's WIAT-II score ( β = .32, p < .001). The Sobel test further confirmed the effect of perceived cognitive competence as an independent mediator (Test statistic = 2.50, p < .05). The hypothesis was partially supported in that the child's perceived cognitive competence mediated the relation between parent involvement and a child's WIAT-II score, but the student-teacher relationship did not. Only the student-teacher relationship was examined as a mediator of the relation between parent involvement and a child's classroom academic performance as the child's perceived cognitive competence was not a significant predictor of the child's classroom academic performance. As shown in Table 3 , parent involvement was no longer a significant predictor of a child's classroom academic performance when the student-teacher relationship was accounted for in the analyses ( β = .07, p = .36). The Sobel test further confirmed the effect of the mediator (Test statistic = 1.90, p = .05).

Regression Analyses Testing Perceived Cognitive Competence and the Student-Teacher Relationship as Multiple Mediators of the Relation Between Parent Involvement and Child's Academic Performance

| B | SE B | β | R | R Change | F Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Examining Mediation of the Relation Between Parent Involvement and Child's WIAT-II score | ||||||

| Step 1. Full Scale IQ | .54 | .06 | .52 | .46 | .46 | 134.93 |

| Step 2. | .58 | .11 | 20.29 | |||

| Perceived Cognitive Competence | 8.12 | 1.45 | .32 | |||

| Student-Teacher Relationship | .05 | .07 | .04 | |||

| Step 3. Parent Involvement | 1.95 | 1.10 | .11 | .58 | .00 | 3.12 |

| Regression Examining Mediation of the Relation Between Parent Involvement and Child's Classroom Academic Performance | ||||||

| Step 1. Full Scale IQ | .03 | .01 | .39 | .22 | .22 | 44.19 |

| Step 2. Student-Teacher Relationship | .02 | .01 | .27 | .31 | .09 | 19.20 |

| Step 3. Parent Involvement | .09 | .10 | .07 | .31 | .00 | .84 |

*p<.05

** p < .01

The purpose of the present study was to examine the ability of the child's perceived cognitive competence and the quality of the student-teacher relationship to explain the relation between parent involvement and the child's academic performance. Findings from the present study demonstrated that increased parent involvement, defined as the teacher's perception of the positive attitude parents have toward their child's education, teacher, and school, was significantly related to increased academic performance, measured by both a standardized achievement test and teacher ratings of the child's classroom academic performance. Further, parent involvement was significantly related to academic performance above and beyond the impact of the child's intelligence (IQ), a variable not accounted for in previous research.

Findings from the present study demonstrated that increased parent involvement is significantly related to a child's increased perception of cognitive competence. This finding is consistent with previous studies ( Gonzalez-DeHass, Willems, & Holbein, 2005 ; Grolnick, Ryan, & Deci, 1991 ). While outside the scope of the present study, it is conceivable that parent involvement may influence the child's perception of cognitive competence by means described by Bandura (1977) . Findings demonstrated that increased parent involvement was significantly related to increased quality of the student-teacher relationship. Findings also demonstrated that increased perceived cognitive competence was related to higher achievement test scores and that the quality of the student-teacher relationship was significantly related to the child's academic performance, measured by both standardized achievement test scores and the child's classroom academic performance. These findings are consistent with previous research and theory ( Chapman, Skinner, & Baltes, 1990 ; Ladd & Price, 1986 ; Schunk, 1981 ). Contrary to what was hypothesized, increased perception of cognitive competence was not significantly related to teacher ratings of academic performance. There may be several reasons for this finding. It may be the tasks children perceive they are competent to complete are not related to actual classroom tasks or that teacher ratings of academic performance are in part based on other variables, such as the child's abilities in other domains independent of the child's academic abilities.