- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Table of Contents

Research Contribution

Definition:

Research contribution refers to a novel and significant addition to a particular field of study that advances the existing knowledge, theories, or practices. It could involve new discoveries, original ideas, innovative methods, or insightful interpretations that contribute to the understanding, development, or improvement of a specific research area.

Research Contribution in Thesis

In a thesis , the research contribution is the original and novel aspect of the research that adds new knowledge to the field. It can be a new theory , a new methodology , a new empirical finding, or a new application of existing knowledge.

To identify the research contribution of your thesis, you need to consider the following:

- What problem are you addressing in your research? What is the research gap that you are filling?

- What is your research question or hypothesis, and how does it relate to the problem you are addressing?

- What methodology have you used to investigate your research question or hypothesis, and why is it appropriate?

- What are the main findings of your research, and how do they contribute to the field?

- What are the implications of your research findings for theory, practice, or policy?

Once you have identified your research contribution, you should clearly articulate it in your thesis abstract, introduction, and conclusion. You should also explain how your research contribution relates to the existing literature and how it advances the field. Finally, you should discuss the limitations of your research and suggest future directions for research that build on your contribution.

How to Write Research Contribution

Here are some steps you can follow to write a strong research contribution:

- Define the research problem and research question : Clearly state the problem or gap in the literature that your research aims to address. Formulate a research question that your study will answer.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: Review the existing literature related to your research question. Identify the gaps in knowledge that your research fills.

- Describe the research design and methodology : Explain the research design, methods, and procedures you used to collect and analyze data. This includes any statistical analysis or data visualization techniques.

- Present the findings: Clearly present your findings, including any statistical analyses or data visualizations that support your conclusions. This should be done in a clear and concise manner, and the conclusions should be based on the evidence you’ve presented.

- Discuss the implications of the findings: Describe the significance of your findings and the implications they have for the field of study. This may include recommendations for future research or practical applications of your findings.

- Conclusion : Summarize the main points of your research contribution and restate its significance.

When to Write Research Contribution in Thesis

A research contribution should be included in the thesis when the research work adds a novel and significant value to the existing body of knowledge. The research contribution section of a thesis is the opportunity for the researcher to articulate the unique contributions their work has made to the field.

Typically, the research contribution section appears towards the end of the thesis, after the literature review, methodology, results, and analysis sections. In this section, the researcher should summarize the key findings and their implications for the field, highlighting the novel aspects of the work.

Example of Research Contribution in Thesis

An example of a research contribution in a thesis can be:

“The study found that there was a significant relationship between social media usage and academic performance among college students. The findings also revealed that students who spent more time on social media had lower GPAs than those who spent less time on social media. These findings are original and contribute to the literature on the impact of social media on academic performance, providing insights that can inform policies and practices for improving students’ academic success.”

Another example of a research contribution in a thesis:

“The research identified a novel method for improving the efficiency of solar panels by incorporating nanostructured materials. The results showed that the use of these materials increased the conversion efficiency of solar panels by up to 30%, which is a significant improvement over traditional methods. This contribution advances the field of renewable energy by providing a new approach to enhancing the performance of solar panels, with potential applications in both residential and commercial settings.”

Purpose of Research Contribution

Purpose of Research Contribution are as follows:

Here are some examples of research contributions that can be included in a thesis:

- Development of a new theoretical framework or model

- Creation of a novel methodology or research approach

- Discovery of new empirical evidence or data

- Application of existing theories or methods in a new context

- Identification of gaps in the existing literature and proposing solutions

- Providing a comprehensive review and analysis of existing literature in a particular field

- Critically evaluating existing theories or models and proposing improvements or alternatives

- Making a significant contribution to policy or practice in a particular field.

Advantages of Research Contribution

Including research contributions in your thesis can offer several advantages, including:

- Establishing originality: Research contributions help demonstrate that your work is original and unique, and not simply a rehashing of existing research. It shows that you have made a new and valuable contribution to the field.

- Adding value to the field : By highlighting your research contributions, you are demonstrating the value that your work adds to the field. This can help other researchers build on your work and advance the field further.

- Differentiating yourself: In academic and professional contexts, it’s important to differentiate yourself from others. Including research contributions in your thesis can help you stand out from other researchers in your field, potentially leading to opportunities for collaboration, networking, or future job prospects.

- Providing clarity : By articulating your research contributions, you are providing clarity to your readers about what you have achieved. This can help ensure that your work is properly understood and appreciated by others.

- Enhancing credibility : Including research contributions in your thesis can enhance your credibility as a researcher, demonstrating that you have the skills and knowledge necessary to make valuable contributions to your field. This can help you build a strong reputation in the academic community.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

How to Publish a Research Paper – Step by Step...

Dissertation Methodology – Structure, Example...

How To Write a Significance Statement for Your Research

A significance statement is an essential part of a research paper. It explains the importance and relevance of the study to the academic community and the world at large. To write a compelling significance statement, identify the research problem, explain why it is significant, provide evidence of its importance, and highlight its potential impact on future research, policy, or practice. A well-crafted significance statement should effectively communicate the value of the research to readers and help them understand why it matters.

Updated on May 4, 2023

A significance statement is a clearly stated, non-technical paragraph that explains why your research matters. It’s central in making the public aware of and gaining support for your research.

Write it in jargon-free language that a reader from any field can understand. Well-crafted, easily readable significance statements can improve your chances for citation and impact and make it easier for readers outside your field to find and understand your work.

Read on for more details on what a significance statement is, how it can enhance the impact of your research, and, of course, how to write one.

What is a significance statement in research?

A significance statement answers the question: How will your research advance scientific knowledge and impact society at large (as well as specific populations)?

You might also see it called a “Significance of the study” statement. Some professional organizations in the STEM sciences and social sciences now recommended that journals in their disciplines make such statements a standard feature of each published article. Funding agencies also consider “significance” a key criterion for their awards.

Read some examples of significance statements from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) here .

Depending upon the specific journal or funding agency’s requirements, your statement may be around 100 words and answer these questions:

1. What’s the purpose of this research?

2. What are its key findings?

3. Why do they matter?

4. Who benefits from the research results?

Readers will want to know: “What is interesting or important about this research?” Keep asking yourself that question.

Where to place the significance statement in your manuscript

Most journals ask you to place the significance statement before or after the abstract, so check with each journal’s guide.

This article is focused on the formal significance statement, even though you’ll naturally highlight your project’s significance elsewhere in your manuscript. (In the introduction, you’ll set out your research aims, and in the conclusion, you’ll explain the potential applications of your research and recommend areas for future research. You’re building an overall case for the value of your work.)

Developing the significance statement

The main steps in planning and developing your statement are to assess the gaps to which your study contributes, and then define your work’s implications and impact.

Identify what gaps your study fills and what it contributes

Your literature review was a big part of how you planned your study. To develop your research aims and objectives, you identified gaps or unanswered questions in the preceding research and designed your study to address them.

Go back to that lit review and look at those gaps again. Review your research proposal to refresh your memory. Ask:

- How have my research findings advanced knowledge or provided notable new insights?

- How has my research helped to prove (or disprove) a hypothesis or answer a research question?

- Why are those results important?

Consider your study’s potential impact at two levels:

- What contribution does my research make to my field?

- How does it specifically contribute to knowledge; that is, who will benefit the most from it?

Define the implications and potential impact

As you make notes, keep the reasons in mind for why you are writing this statement. Whom will it impact, and why?

The first audience for your significance statement will be journal reviewers when you submit your article for publishing. Many journals require one for manuscript submissions. Study the author’s guide of your desired journal to see its criteria ( here’s an example ). Peer reviewers who can clearly understand the value of your research will be more likely to recommend publication.

Second, when you apply for funding, your significance statement will help justify why your research deserves a grant from a funding agency . The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, wants to see that a project will “exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved.” Clear, simple language is always valuable because not all reviewers will be specialists in your field.

Third, this concise statement about your study’s importance can affect how potential readers engage with your work. Science journalists and interested readers can promote and spread your work, enhancing your reputation and influence. Help them understand your work.

You’re now ready to express the importance of your research clearly and concisely. Time to start writing.

How to write a significance statement: Key elements

When drafting your statement, focus on both the content and writing style.

- In terms of content, emphasize the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your research results.

- Write the statement in plain, clear language rather than scientific or technical jargon. Your audience will include not just your fellow scientists but also non-specialists like journalists, funding reviewers, and members of the public.

Follow the process we outline below to build a solid, well-crafted, and informative statement.

Get started

Some suggested opening lines to help you get started might be:

- The implications of this study are…

- Building upon previous contributions, our study moves the field forward because…

- Our study furthers previous understanding about…

Alternatively, you may start with a statement about the phenomenon you’re studying, leading to the problem statement.

Include these components

Next, draft some sentences that include the following elements. A good example, which we’ll use here, is a significance statement by Rogers et al. (2022) published in the Journal of Climate .

1. Briefly situate your research study in its larger context . Start by introducing the topic, leading to a problem statement. Here’s an example:

‘Heatwaves pose a major threat to human health, ecosystems, and human systems.”

2. State the research problem.

“Simultaneous heatwaves affecting multiple regions can exacerbate such threats. For example, multiple food-producing regions simultaneously undergoing heat-related crop damage could drive global food shortages.”

3. Tell what your study does to address it.

“We assess recent changes in the occurrence of simultaneous large heatwaves.”

4. Provide brief but powerful evidence to support the claims your statement is making , Use quantifiable terms rather than vague ones (e.g., instead of “This phenomenon is happening now more than ever,” see below how Rogers et al. (2022) explained it). This evidence intensifies and illustrates the problem more vividly:

“Such simultaneous heatwaves are 7 times more likely now than 40 years ago. They are also hotter and affect a larger area. Their increasing occurrence is mainly driven by warming baseline temperatures due to global heating, but changes in weather patterns contribute to disproportionate increases over parts of Europe, the eastern United States, and Asia.

5. Relate your study’s impact to the broader context , starting with its general significance to society—then, when possible, move to the particular as you name specific applications of your research findings. (Our example lacks this second level of application.)

“Better understanding the drivers of weather pattern changes is therefore important for understanding future concurrent heatwave characteristics and their impacts.”

Refine your English

Don’t understate or overstate your findings – just make clear what your study contributes. When you have all the elements in place, review your draft to simplify and polish your language. Even better, get an expert AJE edit . Be sure to use “plain” language rather than academic jargon.

- Avoid acronyms, scientific jargon, and technical terms

- Use active verbs in your sentence structure rather than passive voice (e.g., instead of “It was found that...”, use “We found...”)

- Make sentence structures short, easy to understand – readable

- Try to address only one idea in each sentence and keep sentences within 25 words (15 words is even better)

- Eliminate nonessential words and phrases (“fluff” and wordiness)

Enhance your significance statement’s impact

Always take time to review your draft multiple times. Make sure that you:

- Keep your language focused

- Provide evidence to support your claims

- Relate the significance to the broader research context in your field

After revising your significance statement, request feedback from a reading mentor about how to make it even clearer. If you’re not a native English speaker, seek help from a native-English-speaking colleague or use an editing service like AJE to make sure your work is at a native level.

Understanding the significance of your study

Your readers may have much less interest than you do in the specific details of your research methods and measures. Many readers will scan your article to learn how your findings might apply to them and their own research.

Different types of significance

Your findings may have different types of significance, relevant to different populations or fields of study for different reasons. You can emphasize your work’s statistical, clinical, or practical significance. Editors or reviewers in the social sciences might also evaluate your work’s social or political significance.

Statistical significance means that the results are unlikely to have occurred randomly. Instead, it implies a true cause-and-effect relationship.

Clinical significance means that your findings are applicable for treating patients and improving quality of life.

Practical significance is when your research outcomes are meaningful to society at large, in the “real world.” Practical significance is usually measured by the study’s effect size . Similarly, evaluators may attribute social or political significance to research that addresses “real and immediate” social problems.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

The Why: Explaining the significance of your research

In the first four articles of this series, we examined The What: Defining a research project , The Where: Constructing an effective writing environment , The When: Setting realistic timeframes for your research , and The Who: Finding key sources in the existing literature . In this article, we will explore the fifth, and final, W of academic writing, The Why: Explaining the significance of your research.

Q1: When considering the significance of your research, what is the general contribution you make?

According to the Unite for Sight online module titled “ The Importance of Research ”:

“The purpose of research is to inform action. Thus, your study should seek to contextualize its findings within the larger body of research. Research must always be of high quality in order to produce knowledge that is applicable outside of the research setting. Furthermore, the results of your study may have implications for policy and future project implementation.”

In response to this TweetChat question, Twitter user @aemidr shared that the “dissemination of the research outcomes” is their contribution. Petra Boynton expressed a contribution of “easy to follow resources other people can use to help improve their health/wellbeing”.

Eric Schmieder said, “In general, I try to expand the application of technology to improve the efficiency of business processes through my research and personal use and development of technology solutions.” While Janet Salmons offered the response, “ I am a metaresearcher , that is, I research emerging qualitative methods & write about them. I hope contribution helps student & experienced researchers try new approaches.”

Despite the different contributions each of these participants noted as the significance of their individual research efforts, there is a significance to each. In addition to the importance stated through the above examples, Leann Zarah offered 7 Reasons Why Research Is Important , as follows:

- A Tool for Building Knowledge and for Facilitating Learning

- Means to Understand Various Issues and Increase Public Awareness

- An Aid to Business Success

- A Way to Prove Lies and to Support Truths

- Means to Find, Gauge, and Seize Opportunities

- A Seed to Love Reading, Writing, Analyzing, and Sharing Valuable Information

- Nourishment and Exercise for the Mind

Q1a: What is the specific significance of your research to yourself or other individuals?

The first of “ 3 Important Things to Consider When Selecting Your Research Topic ”, as written by Stephen Fiedler is to “choose something that interests you”. By doing so, you are more likely to stay motivated and persevere through inevitable challenges.

As mentioned earlier, for Salmons her interests lie in emerging methods and new approaches to research. As Salmons pointed out in the TweetChat, “Conventional methods may not be adequate in a globally-connected world – using online methods expands potential participation.”

For @aemidr, “specific significance of my research is on health and safety from the environment and lifestyle”. In contrast, Schmieder said “my ongoing research allows me to be a better educator, to be more efficient in my own business practices, and to feel comfortable engaging with new technology”.

Regardless of discipline, a personal statement can help identify for yourself and others your suitability for specific research. Some things to include in the statement are:

- Your reasons for choosing your topic of research

- The aspects of your topic of research that interest you most

- Any work experience, placement or voluntary work you have undertaken, particularly if it is relevant to your subject. Include the skills and abilities you have gained from these activities

- How your choice of research fits in with your future career plans

Q2: Why is it important to communicate the value of your research?

According to Salmons, “If you research and no one knows about it or can use what you discover, it is just an intellectual exercise. If we want the public to support & fund research, we must show why it’s important!” She has written for the SAGE MethodSpace blog on the subject Write with Purpose, Publish for Impact building a collection of articles from both the MethodSpace blog and TAA’s blog, Abstract .

Peter J. Stogios shares with us benefits to both the scientist and the public in his article, “ Why Sharing Your Research with the Public is as Necessary as Doing the Research Itself ”. Unsure where to start? Stogios states, “There are many ways scientists can communicate more directly with the public. These include writing a personal blog, updating their lab’s or personal website to be less technical and more accessible to non-scientists, popular science forums and message boards, and engaging with your institution’s research communication office. Most organizations publish newsletters or create websites showcasing the work being done, and act as intermediaries between the researchers and the media. Scientists can and should interact more with these communicators.”

Schmieder stated during the TweetChat that the importance of communicating the value of your research is “primarily to help others understand why you do what you do, but also for funding purposes, application of your results by others, and increased personal value and validation”.

In her article, “ Explaining Your Research to the Public: Why It Matters, How to Do It! ”, Sharon Page-Medrich conveys the importance, stating “UC Berkeley’s 30,000+ undergraduate and 11,000+ graduate students generate or contribute to diverse research in the natural and physical sciences, social sciences and humanities, and many professional fields. Such research and its applications are fundamental to saving lives, restoring healthy environments, making art and preserving culture, and raising standards of living. Yet the average person-in-the-street may not see the connection between students’ investigations and these larger outcomes.”

Q2a: To whom is it most difficult to explain that value?

Although important, it’s not always easy to share our research efforts with others. Erin Bedford sets the scene as she tells us “ How to (Not) Talk about Your Research ”. “It’s happened to the best of us. First, the question: ‘so, what is your research on?’ Then, the blank stare as you try to explain. And finally, the uninterested but polite nod and smile.”

Schmieder acknowledges that these polite people who care enough to ask, but often are the hardest to explain things to are “family and friends who don’t share the same interests or understanding of the subject matter.” It’s not that they don’t care about the efforts, it’s that the level to which a researcher’s investment and understanding is different from those asking about their work.

When faced with less-than-supportive reactions from friends, Noelle Sterne shares some ways to retain your perspective and friendship in her TAA blog article, “ Friends – How to deal with their negative responses to your academic projects ”.

Q3: What methods have you used to explain your research to others (both inside and outside of your discipline)?

Schmieder stated, “I have done webinars, professional development seminars, blog articles, and online courses” in an effort to communicate research to others. The Edinburg Napier University LibGuides guide to Sharing Your Research includes some of these in their list of resources as well adding considerations of online presence, saving time / online efficiency, copyright, and compliance to the discussion.

Michaela Panter states in her article, “ Sharing Your Findings with a General Audience ”, that “tips and guidelines for conveying your research to a general audience are increasingly widespread, yet scientists remain wary of doing so.” She notes, however, that “effectively sharing your research with a general audience can positively affect funding for your work” and “engaging the general public can further the impact of your research”.

If these are affects you desire, consider CES’s “ Six ways to share your research findings ”, as follows:

- Know your audience and define your goal

- Collaborate with others

- Make a plan

- Embrace plain language writing

- Layer and link, and

- Evaluate your work

Q4: What are some places you can share your research and its significance beyond your writing?

Beyond traditional journal article publication efforts, there are many opportunities to share your research with a larger community. Schmieder listed several options during the TweetChat event, specifically, “conference presentations, social media, blogs, professional networks and organizations, podcasts, and online courses”.

Elsevier’s resource, “ Sharing and promoting your article ” provides advice on sharing your article in the following ten places:

- At a conference

- For classroom teaching purposes

- For grant applications

- With my colleagues

- On a preprint server

- On my personal blog or website

- On my institutional repository

- On a subject repository (or other non-commercial repository)

- On Scholarly Communication Network (SCN), such as Mendeley or Scholar Universe

- Social Media, such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter

Nature Publishing Group’s “ tips for promoting your research ” include nine ways to get started:

- Share your work with your social networks

- Update your professional profile

- Utilize research-sharing platforms

- Create a Google Scholar profile – or review and enhance your existing one

- Highlight key and topical points in a blog post

- Make your research outputs shareable and discoverable

- Register for a unique ORCID author identifier

- Encourage readership within your institution

Finally, Sheffield Solutions produced a top ten list of actions you can take to help share and disseminate your work more widely online, as follows:

- Create an ORCID ID

- Upload to Sheffield’s MyPublications system

- Make your work Open Access

- Create a Google Scholar profile

- Join an academic social network

- Connect through Twitter

- Blog about your research

- Upload to Slideshare or ORDA

- Track your research

Q5: How is the significance of your study conveyed in your writing efforts?

Schmieder stated, “Significance is conveyed through the introduction, the structure of the study, and the implications for further research sections of articles”. According to The Writing Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “A thesis statement tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion”.

In their online Tips & Tools resource on Thesis Statements , they share the following six questions to ask to help determine if your thesis is strong:

- Do I answer the question?

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose?

- Is my thesis statement specific enough?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test?

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test?

Some journals, such as Elsevier’s Acta Biomaterialia, now require a statement of significance with manuscript submissions. According to the announcement linked above, “these statements will address the novelty aspect and the significance of the work with respect to the existing literature and more generally to the society.” and “by highlighting the scientific merit of your research, these statements will help make your work more visible to our readership.”

Q5a: How does the significance influence the structure of your writing?

According to Jeff Hume-Pratuch in the Academic Coaching & Writing (ACW) article, “ Using APA Style in Academic Writing: Precision and Clarity ”, “The need for precision and clarity of expression is one of the distinguishing marks of academic writing.” As a result, Hume-Pratuch advises that you “choose your words wisely so that they do not come between your idea and the audience.” To do so, he suggests avoiding ambiguous expressions, approximate language, and euphemisms and jargon in your writing.

Schmieder shared in the TweetChat that “the impact of the writing is affected by the target audience for the research and can influence word choice, organization of ideas, and elements included in the narrative”.

Discussing the organization of ideas, Patrick A. Regoniel offers “ Two Tips in Writing the Significance of the Study ” claiming that by referring to the statement of the problem and writing from general to specific contribution, you can “prevent your mind from wandering wildly or aimlessly as you explore the significance of your study”.

Q6: What are some ways you can improve your ability to explain your research to others?

For both Schmieder and Salmons, practice is key. Schmieder suggested, “Practice simplifying the concepts. Focus on why rather than what. Share research in areas where they are active and comfortable”. Salmons added, “answer ‘so what’ and ‘who cares’ questions. Practice creating a sentence. For my study of the collaborative process: ‘Learning to collaborate is important for team success in professional life’ works better than ‘a phenomenological study of instructors’ perceptions’”.

In a guest blog post for Scientific American titled “ Effective Communication, Better Science ”, Mónica I. Feliú-Mójer claimed “to be a successful scientist, you must be an effective communicator.” In support of the goal of being an effective communicator, a list of training opportunities and other resources are included in the article.

Along the same lines, The University of Melbourne shared the following list of resources, workshops, and programs in their online resource on academic writing and communication skills :

- Speaking and Presenting : Resources for presenting your research, using PowerPoint to your advantage, presenting at conferences and helpful videos on presenting effectively

- Research Impact Library Advisory Service (RILAS): Helps you to determine the impact of your publications and other research outputs for academic promotions and grant applications

- Three Minute Thesis Competition (3MT): Research communication competition that requires you to deliver a compelling oration on your thesis topic and its significance in just three minutes or less.

- Visualise your Thesis Competition : A dynamic and engaging audio-visual “elevator pitch” (e-Poster) to communicate your research to a broad non-specialist audience in 60 seconds.

As we complete this series exploration of the five W’s of academic writing, we hope that you are adequately prepared to apply them to your own research efforts of defining a research project, constructing an effective writing environment, setting realistic timeframes for your research, finding key sources in the existing literature, and last, but not least, explaining the significance of your research.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Please note that all content on this site is copyrighted by the Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Individual articles may be reposted and/or printed in non-commercial publications provided you include the byline (if applicable), the entire article without alterations, and this copyright notice: “© 2024, Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Originally published on the TAA Blog, Abstrac t on [Date, Issue, Number].” A copy of the issue in which the article is reprinted, or a link to the blog or online site, should be mailed to Kim Pawlak P.O. Box 337, Cochrane, WI 54622 or Kim.Pawlak @taaonline.net.

Crafting Powerful Conclusions: Summarizing Your Research's Significance

In the realm of scholarly writing, the conclusion serves as the final impression you leave on your readers. It's the space where you synthesize the entirety of your research journey and offer a lasting takeaway. Crafting a powerful conclusion goes beyond restating findings; it involves highlighting the significance of your research and providing a sense of closure. Here's how to ensure your conclusion is a compelling reflection of your scholarly endeavor.

Recapitulate Key Findings

In the culmination of your research manuscript, the conclusion acts as a bridge between the comprehensive exploration of your study and the lasting impression you leave on readers. At the forefront of this conclusion is the task of recapitulating the key findings that your research has unearthed.

In this section, you distill the intricate web of data, analysis, and interpretation into a concise summary. Avoid the temptation to reiterate every detail; instead, focus on the pivotal discoveries that drive the narrative of your research. Address each key finding sequentially, providing a succinct overview of the results you have meticulously detailed in the body of your manuscript.

The goal is to offer a snapshot of your research's most significant contributions. By doing so, you help readers recall the core insights without overwhelming them with extensive technicalities. This concise recapitulation also aids in framing the subsequent discussions that delve deeper into the implications of your findings.

To achieve an effective recapitulation:

Prioritize Significance: Select findings that are central to your research question and that have the most substantial impact on advancing knowledge in your field.

Brevity is Key: Present your key findings succinctly. Aim for clarity while avoiding redundancy.

Maintain Accuracy: Ensure that your recapitulation accurately reflects the nuances of your findings. Avoid oversimplification that could misrepresent your research.

Avoid New Information: Resist introducing new data or findings in this section. Stick to the results that have already been discussed in the body of your manuscript.

Receive Free Grammar and Publishing Tips via Email

Address the research question.

In the realm of scholarly exploration, every research endeavor begins with a question or hypothesis. As you craft the conclusion of your manuscript, it's imperative to revisit this foundational inquiry and reflect on how your research has addressed it.

In this section, you bring your research full circle by evaluating the extent to which your findings have provided insights into the original research question. Start by rephrasing the question and reminding readers of the intellectual journey that led you to this point. Then, proceed to highlight how your study has contributed to the broader understanding of the topic.

Effective strategies for addressing the research question:

Clear Alignment: Emphasize the alignment between your research question and the scope of your study. Explain how your investigation has provided clarity or new dimensions to the initial query.

Answering the Question: Articulate how your findings directly address the research question. Discuss the extent to which your study has provided evidence or insights in response to this question.

Contribution to Knowledge: Elaborate on how your research outcomes have added to the body of knowledge in your field. If your findings confirm, refute, or modify existing theories, discuss these implications.

Limitations and Nuances: Acknowledge any limitations in fully addressing the research question. Reflect on areas where further research is needed to provide a comprehensive understanding.

Conceptual Implications: Consider the conceptual impact of your findings. Do they challenge existing paradigms, expand theoretical frameworks, or propose new avenues of exploration?

Synthesis: In this section, you synthesize the intellectual journey of your research. Summarize how your investigation, data collection, analysis, and interpretation have collectively contributed to addressing the research question.

Emphasize Significance

As your research manuscript nears its conclusion, a crucial aspect to highlight is the significance of your findings. This section provides the opportunity to convey the broader impact and relevance of your research within the academic and practical spheres.

In this segment, you elucidate why your research matters, both within the context of your specific field and beyond. Your goal is to convince readers that your findings have implications that extend beyond the confines of your study.

To effectively emphasize the significance of your research:

Contextual Relevance: Begin by placing your findings within the context of the existing body of knowledge. Highlight gaps or areas that your research addresses and how it contributes to the ongoing discourse.

Addressing a Problem: If your research addresses a specific problem or challenge, underscore how your findings offer solutions or insights that have the potential to create positive change.

Practical Applications: Discuss practical applications of your research. How can your findings be applied in real-world scenarios? Emphasize the potential benefits to industries, communities, or policies.

Contributions to Theory: If your research contributes to theoretical frameworks, discuss how your insights refine or reshape existing theories. Explain how your work advances the understanding of fundamental concepts.

Advancing Knowledge: Highlight how your research contributes to the advancement of knowledge in your field. Articulate how your findings extend beyond the scope of your specific study to impact the broader academic landscape.

Addressing Grand Challenges: If your research aligns with broader societal challenges (e.g., climate change, health disparities), emphasize how your findings align with efforts to address these issues.

Potential Paradigm Shifts: If your research challenges conventional wisdom or opens new avenues of thought, discuss the potential for paradigm shifts and transformative thinking in your field.

Long-Term Implications: Consider the long-term implications of your findings. How might they shape future research directions or influence policy decisions?

Contextualize with Literature

In the final stretch of your research manuscript, the section dedicated to contextualizing your findings with existing literature plays a pivotal role. This segment offers an opportunity to situate your research within the broader academic landscape, showcasing how your contributions align, diverge, or extend previous scholarly work.

Contextualizing your findings with literature involves more than just referencing related studies; it's about weaving your research into the ongoing scholarly conversation. Here's how to effectively achieve this in your conclusion:

Revisit Relevant Studies: Begin by revisiting studies that are closely related to your research. Summarize their key findings and insights, ensuring you accurately represent their contributions.

Highlight Alignments: Identify areas where your findings align with existing literature. Do your results confirm or reinforce previous conclusions? Highlight these agreements to emphasize the validity of your study.

Discuss Departures: If your findings diverge from established theories or studies, discuss these deviations. Are there legitimate reasons for the differences? Analyze potential reasons for the disparities.

Bridge Gaps: Address gaps in the literature that your research helps bridge. Explain how your findings fill in missing pieces or provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Extend Frameworks: If your research extends or refines theoretical frameworks, explain how your insights contribute to a deeper comprehension of key concepts.

Contrast and Compare: Compare methodologies, scope, and conclusions with studies that share similarities. Highlight where your approach offers fresh perspectives or methodological advancements.

Contextualizing your findings within the existing literature elevates your research from an isolated study to a thread within the fabric of academic inquiry. It demonstrates your awareness of the broader conversation and positions your work as a valuable addition. By carefully navigating this section, you engage in scholarly dialogue, showing how your research both complements and advances the field's collective knowledge.

Highlight Limitations

No research is without its limitations, and acknowledging these constraints is a hallmark of scholarly integrity. In the conclusion of your manuscript, the "Highlight Limitations" section provides an opportunity to openly address the boundaries and potential vulnerabilities of your study.

The purpose of highlighting limitations is not to undermine your research but to provide a balanced perspective. By acknowledging these constraints, you demonstrate a nuanced understanding of the complexities inherent in scientific inquiry. Here's how to effectively address limitations:

Transparency: Approach this section with transparency and honesty. Readers value researchers who openly discuss the challenges they encountered.

Scope and Generalizability: Discuss the scope of your study and its implications for generalizability. Are the findings specific to a certain context, population, or time frame? Explain how these limitations may affect the broader applicability of your results.

Methodological Constraints: Address any methodological limitations that could impact the validity of your findings. Were there constraints in data collection, sample size, or experimental design? Acknowledge how these factors may influence the interpretation of your results.

Data Limitations: If your research relies on specific datasets, discuss the limitations of these data sources. Are there potential biases or gaps in the data that readers should be aware of?

Unanswered Questions: Identify questions that your research could not fully address. These could serve as future research directions or avenues for further exploration.

Impact on Conclusions: Be transparent about how limitations may have impacted your conclusions. Discuss whether these limitations introduce uncertainty or require cautious interpretation of your results.

Mitigation Efforts: If you took steps to mitigate limitations, such as using alternative methodologies or cross-referencing data sources, discuss these efforts and their potential impact.

By highlighting limitations, you demonstrate your commitment to rigorous scholarship and the advancement of knowledge. This section showcases your ability to critically evaluate your research and provides readers with a comprehensive understanding of the context in which your findings should be interpreted. A well-considered discussion of limitations adds depth to your manuscript and contributes to the overall credibility of your work.

Propose Future Directions

As the conclusion of your research manuscript approaches, you have the opportunity to shift your focus from the past to the future. In the "Propose Future Directions" section, you outline potential pathways for research that can build upon and extend the foundation you've laid in your study.

This forward-looking section demonstrates your commitment to the ongoing advancement of knowledge and provides a roadmap for fellow researchers who may be inspired by your work. Here's how to effectively propose future directions:

Research Gaps: Identify gaps in your study that warrant further investigation. Are there unanswered questions or unexplored aspects of the topic that you've encountered during your research?

Unresolved Issues: Highlight any issues or complexities that emerged during your study but were beyond the scope of your research. Suggest how future studies could tackle these challenges.

Methodological Innovations: If your research uncovered methodological limitations, propose innovative approaches that could address these constraints in future research.

Emerging Trends: Discuss emerging trends or developments in your field that could be explored in subsequent studies. How might your findings intersect with these new areas of inquiry?

Application and Impact: Explore potential real-world applications of your research findings. How might your insights be applied in practical contexts, and what impact could they have?

Invoke a Sense of Closure

As you approach the final moments of your research manuscript, it's essential to craft a conclusion that leaves readers with a sense of closure. The "Invoke a Sense of Closure" section provides a satisfying ending to your narrative, encapsulating the journey you've taken them on and leaving a lasting impression.

In this section, you guide readers through the final moments of reflection and synthesis. Your goal is to convey that your research has reached its natural endpoint and that its significance lingers even after the final words. Here's how to effectively invoke a sense of closure:

Summarize Key Points: Begin by summarizing the key findings, insights, and contributions of your study. Provide a concise overview of what readers have learned through your research journey.

Circle Back to the Beginning: Consider revisiting the opening paragraphs of your introduction. Have you fulfilled the promises you made at the outset? Use this opportunity to connect the dots and reflect on the fulfillment of those promises.

Reflect on the Journey: Reflect on the intellectual journey you've taken readers on. Acknowledge the challenges, surprises, and revelations that unfolded as you delved into the research process.

Reiterate Significance: Reiterate the significance of your research in the broader context. Reinforce how your findings contribute to the advancement of knowledge and the understanding of the topic.

Inspire Further Thought: Leave readers with a thought-provoking statement or question that invites further contemplation. Encourage them to continue thinking about the implications of your research.

Connect to Bigger Picture: Situate your study within the grander narrative of the field. How does your work contribute to the ongoing conversation? Emphasize the continuity of scholarly inquiry.

Express Gratitude: If appropriate, express gratitude for the support, resources, and collaborations that made your research possible. Acknowledge the contributions of mentors, peers, and institutions.

Evoke Emotion: Use language that evokes emotion and resonates with readers. A sense of poignancy and reflection can create a lasting impression.

In essence, a well-crafted conclusion serves as the grand finale of your scholarly narrative. By recapping key findings, addressing the research question, emphasizing significance, contextualizing with literature, highlighting limitations, proposing future directions, invoking closure, and conveying enthusiasm, you create a conclusion that resonates and underscores the importance of your research contribution.

Connect With Us

Dissertation Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

May 3, 2017.

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our professional dissertation editing se...

Thesis Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our thesis editing service is discounted...

Neurology includes Falcon Scientific Editing in Professional Editing Help List

March 14, 2017.

Neurology Journal now includes Falcon Scientific Editing in its Professio...

Useful Links

Academic Editing | Thesis Editing | Editing Certificate | Resources

How to make an original contribution to knowledge

“The thesis can address small gaps within saturated research areas.”

When PhD candidates embark on their thesis journey, the first thing they will likely learn is that their research must be a “significant original contribution to knowledge.” On the face of it, the idea seems simple enough: create something new, establish a niche for oneself, further science and add some important piece to the sum of human understanding. And yet, there is little to no consensus as to what exactly this phrase means. This lack of consensus is particularly challenging for students, as it opens them up to risk in matters of external review and their graduate school progression.

Aside from the risk it poses to student’s success (for example, attrition), an ill-defined standard for the contribution to knowledge creates risks for the student during the external examination of the thesis. This can happen in two ways.

First, an external examiner may have biases towards pet theories or concepts and may dismiss the work if he or she does not agree with the opinions presented. Arguably more disastrous, supervisors themselves may recommend that a thesis be put forward for defence which the external examiner feels is not significant. This misplaced confidence can result in the entire work being disregarded, or the shattering award of a conciliatory master of philosophy.

Fortunately, there are ways to both clarify the concept of a significant original contribution to knowledge and to prepare to defend it. After all, “to escape with a PhD, you must meaningfully extend the boundary of human knowledge. More exactly, you must convince a panel of experts guarding the boundary that you have done so,” says Matt Might, an assistant professor at the University of Utah and author of The Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D .

The first step for PhD students is to recognize that a thesis will be built on other people’s work in a rigorous, precise way and is not expected to lead to an immediate and fundamental paradigm shift in the field. On this point, the best PhD theses investigate a circumscribed area, rather than overselling the originality or expertise. The significant original contribution emerges from small gaps within saturated research areas as novel interpretations or applications of old ideas. The researcher can accomplish this in many ways, for example, by creating a synthesis, by providing a single original technique, or by testing existing knowledge in an original manner. Although the thesis has to be innovative, this doesn’t necessarily mean revolutionizing the existing discourse; there is also value in adding new perspectives.

Similarly, and partly because of the time required to complete a doctoral degree, students must resist becoming wrapped up in what they’re looking at in the moment and thus forgetting the big picture. This is especially true for people writing manuscript-style theses in the natural sciences, which represent many small parts of an overarching idea and contribution.

To mitigate this tendency to digress, and to supress any panic around a “crisis of meaning,” doctoral students should at all times be able to summarize their significant original contribution in two sentences. From an examiner’s perspective, it is critical to include this in the dissertation itself – nailing it in the second sentence of the abstract allows the examiner to focus on the justification and verification of this statement. Having a well-bounded and clear idea of one’s contribution contextualizes the work and can protect the student from undue criticism.

Ultimately, it is up to the individual candidates to justify their significant original contribution. Being aware of the indistinctness of these criteria, they must make a concentrated effort to keep track of this contribution, be able to defend it and keep it at the forefront of their minds when their confidence begins to flag. This is always an iterative process, starting with a literature review and later comparing results against the significance of other works.

To protect themselves against overconfidence and insularity, students must look beyond their supervisor and department throughout their PhD program by trying to publish, presenting papers at conferences and discussing the work in as many spheres as possible to get feedback. These activities will not only serve to bolster the inward and outward argument for the research but will also help manage the risk of receiving a nasty surprise when it comes time to defend.

Making a small, significant contribution to knowledge remains the standard against which a PhD dissertation is measured; for their own sake and the sake of their research, students must learn to embrace it.

Heather Cray is a doctoral student in the department of environment and resource studies at the University of Waterloo.

Other stories that might be of interest:

- The PhD is in need of revision

- Margin Notes | PhD completion rates and times to completion in Canada

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Thanks for this issue raised here. it has been a problem eating me up. I am just finalising a doctoral in Mathematics, but the contribution to knowledge is not too clear to me. reading through this piece however kindled something in me. How I wish some specific s were given in the sciences, it could help further. thanks anyway.

Hi, thank you for this great article. I have read it a couple times and have saved it for future reference to help other colleagues.

Could you please clarify one thing? Thank you.

Are you saying that filling a gap is what will become the contribution to knowledge. I.e let’s say I notice that there is a limited exploration of x so the purpose of this study is to a b c. Is ABC my contribution to knowledge? Thank you in advance.

Very interesting article! At what point and to what extent would the “contribution to knowledge” be simply that? While I appreciate the relevance of your article, I agree with the above comment about vagueness. How DOES one relay the “knowledge” to research and make it applicable?

Oh, great! Thank you for this concise discourse. It demystifies the misunderstanding around Contribution to Knowledge. Very helpful.

I am a student in a professional doctorate program in the UK. I am having a great difficulty with my advisor on exactly this issue. What is the original contribution to knowledge of my project. I chose a Health Policy research project that will showcase the state of a certain health system with regards to oncology care and it will evaluate the quality of clinical care based on the current standard of care. This a study that hasn’t been done before and I feel that this is my original contribution to knowledge. My advisor insists that this is a needs assessment and that there is no original contribution to knowledge. This issue has been bringing me down for about 2 years now. I don’t know what to do. Any help is greatly appreciated.

Original contribution doesn’t have to be about inventing the wheel. It boils down to you looking at the gap in literature, theory and praxis which your work is filling. Look at what you have brought newly which previous studies have not considered. You perspective to the issue is the original knowledge you are bringing to the table.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

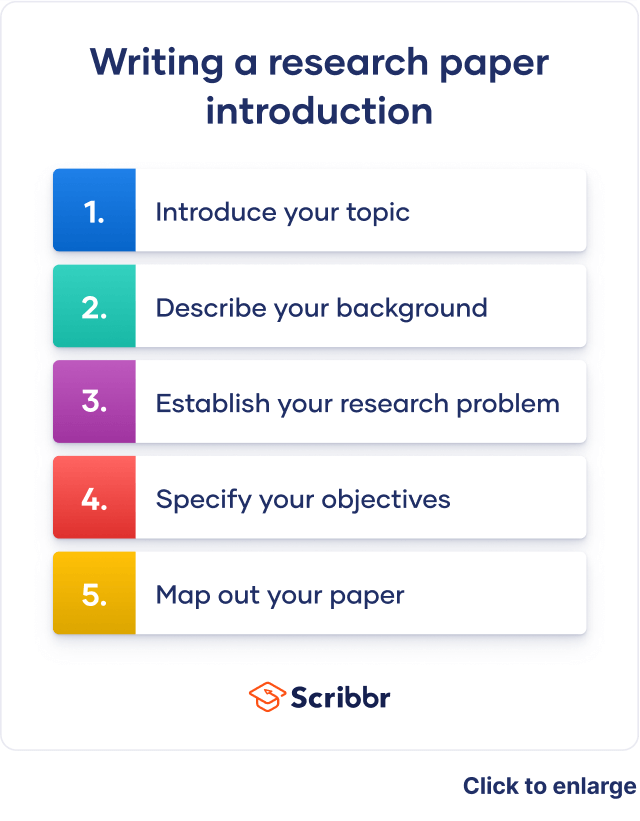

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, March 27). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Discuss the Significance of Your Research

6-minute read

- 10th April 2023

Introduction

Research papers can be a real headache for college students . As a student, your research needs to be credible enough to support your thesis statement. You must also ensure you’ve discussed the literature review, findings, and results.

However, it’s also important to discuss the significance of your research . Your potential audience will care deeply about this. It will also help you conduct your research. By knowing the impact of your research, you’ll understand what important questions to answer.

If you’d like to know more about the impact of your research, read on! We’ll talk about why it’s important and how to discuss it in your paper.

What Is the Significance of Research?

This is the potential impact of your research on the field of study. It includes contributions from new knowledge from the research and those who would benefit from it. You should present this before conducting research, so you need to be aware of current issues associated with the thesis before discussing the significance of the research.

Why Does the Significance of Research Matter?

Potential readers need to know why your research is worth pursuing. Discussing the significance of research answers the following questions:

● Why should people read your research paper ?

● How will your research contribute to the current knowledge related to your topic?

● What potential impact will it have on the community and professionals in the field?

Not including the significance of research in your paper would be like a knight trying to fight a dragon without weapons.

Where Do I Discuss the Significance of Research in My Paper?

As previously mentioned, the significance of research comes before you conduct it. Therefore, you should discuss the significance of your research in the Introduction section. Your reader should know the problem statement and hypothesis beforehand.

Steps to Discussing the Significance of Your Research

Discussing the significance of research might seem like a loaded question, so we’ve outlined some steps to help you tackle it.

Step 1: The Research Problem

The problem statement can reveal clues about the outcome of your research. Your research should provide answers to the problem, which is beneficial to all those concerned. For example, imagine the problem statement is, “To what extent do elementary and high school teachers believe cyberbullying affects student performance?”

Learning teachers’ opinions on the effects of cyberbullying on student performance could result in the following:

● Increased public awareness of cyberbullying in elementary and high schools

● Teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying negatively affecting student performance

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Whether cyberbullying is more prevalent in elementary or high schools

The research problem will steer your research in the right direction, so it’s best to start with the problem statement.

Step 2: Existing Literature in the Field

Think about current information on your topic, and then find out what information is missing. Are there any areas that haven’t been explored? Your research should add new information to the literature, so be sure to state this in your discussion. You’ll need to know the current literature on your topic anyway, as this is part of your literature review section .

Step 3: Your Research’s Impact on Society

Inform your readers about the impact on society your research could have on it. For example, in the study about teachers’ opinions on cyberbullying, you could mention that your research will educate the community about teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying as it affects student performance. As a result, the community will know how many teachers believe cyberbullying affects student performance.

You can also mention specific individuals and institutions that would benefit from your study. In the example of cyberbullying, you might indicate that school principals and superintendents would benefit from your research.

Step 4: Future Studies in the Field

Next, discuss how the significance of your research will benefit future studies, which is especially helpful for future researchers in your field. In the example of cyberbullying affecting student performance, your research could provide further opportunities to assess teacher perceptions of cyberbullying and its effects on students from larger populations. This prepares future researchers for data collection and analysis.

Discussing the significance of your research may sound daunting when you haven’t conducted it yet. However, an audience might not read your paper if they don’t know the significance of the research. By focusing on the problem statement and the research benefits to society and future studies, you can convince your audience of the value of your research.

Remember that everything you write doesn’t have to be set in stone. You can go back and tweak the significance of your research after conducting it. At first, you might only include general contributions of your study, but as you research, your contributions will become more specific.

You should have a solid understanding of your topic in general, its associated problems, and the literature review before tackling the significance of your research. However, you’re not trying to prove your thesis statement at this point. The significance of research just convinces the audience that your study is worth reading.

Finally, we always recommend seeking help from your research advisor whenever you’re struggling with ideas. For a more visual idea of how to discuss the significance of your research, we suggest checking out this video .

1. Do I need to do my research before discussing its significance?

No, you’re discussing the significance of your research before you conduct it. However, you should be knowledgeable about your topic and the related literature.

2. Is the significance of research the same as its implications?

No, the research implications are potential questions from your study that justify further exploration, which comes after conducting the research.

3. Discussing the significance of research seems overwhelming. Where should I start?

We recommend the problem statement as a starting point, which reveals clues to the potential outcome of your research.

4. How can I get feedback on my discussion of the significance of my research?

Our proofreading experts can help. They’ll check your writing for grammar, punctuation errors, spelling, and concision. Submit a 500-word document for free today!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

May 23rd, 2013

Clear articulation of scholarly contribution is essential in academic writing.

2 comments | 16 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes