- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Introduce Evidence: 41 Effective Phrases & Examples

Research requires us to scrutinize information and assess its credibility. Accordingly, when we think about various phenomena, we examine empirical data and craft detailed explanations justifying our interpretations. An essential component of constructing our research narratives is thus providing supporting evidence and examples.

The type of proof we provide can either bolster our claims or leave readers confused or skeptical of our analysis. Therefore, it’s crucial that we use appropriate, logical phrases that guide readers clearly from one idea to the next. In this article, we explain how evidence and examples should be introduced according to different contexts in academic writing and catalog effective language you can use to support your arguments, examples included.

When to Introduce Evidence and Examples in a Paper

Evidence and examples create the foundation upon which your claims can stand firm. Without proof, your arguments lack credibility and teeth. However, laundry listing evidence is as bad as failing to provide any materials or information that can substantiate your conclusions. Therefore, when you introduce examples, make sure to judiciously provide evidence when needed and use phrases that will appropriately and clearly explain how the proof supports your argument.

There are different types of claims and different types of evidence in writing. You should introduce and link your arguments to evidence when you

- state information that is not “common knowledge”;

- draw conclusions, make inferences, or suggest implications based on specific data;

- need to clarify a prior statement, and it would be more effectively done with an illustration;

- need to identify representative examples of a category;

- desire to distinguish concepts; and

- emphasize a point by highlighting a specific situation.

Introductory Phrases to Use and Their Contexts

To assist you with effectively supporting your statements, we have organized the introductory phrases below according to their function. This list is not exhaustive but will provide you with ideas of the types of phrases you can use.

| stating information that is not “common knowledge” | ] | |

| drawing conclusions, making inferences, or suggesting implications based on specific data | ||

| clarifying a prior statement | ||

| identifying representative examples of a category |

*NOTE: “such as” and “like” have two different uses. “Such as” introduces a specific example that is part of a category. “Like” suggests the listed items are similar to, but not included in, the topic discussed. | |

| distinguishing concepts | ||

| emphasizing a point by highlighting a specific situation |

Although any research author can make use of these helpful phrases and bolster their academic writing by entering them into their work, before submitting to a journal, it is a good idea to let a professional English editing service take a look to ensure that all terms and phrases make sense in the given research context. Wordvice offers paper editing , thesis editing , and dissertation editing services that help elevate your academic language and make your writing more compelling to journal authors and researchers alike.

For more examples of strong verbs for research writing , effective transition words for academic papers , or commonly confused words , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources website.

25 Best Transition Words for Providing Evidence

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Transition words and phrases for providing evidence include “For example,”, “Evidence shows”, “A study found”, and “To demonstrate this point”.

These transition words and phrases can smooth the transition from one sentence to the next and help guide your reader, as shown below:

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. In fact, a 2021 literature review found that 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

If you have an entire paragraph dedicated to outlining evidence for your argument, you may want a transition word at the start of the paragraph (see examples) that indicates to your reader that you are about to provide evidence for statements made in a previous paragraph.

Shortlist of Transition Words for Evidence

- To illustrate this point…

- As can be seen in…

- To demonstrate,…

- Evidence of this fact can be seen in…

- Proof of this point is found in…

- For instance,…

- For one thing,…

- Compelling evidence shows…

- For a case in point, readers should look no further than…

- In fact, one study finds…

- New evidence has found…

- Evidence shows…

- In view of recent evidence,…

- Notably, one study found…

- A seminal study has found…

- According to…

- In the article…

- Three separate studies have found…

- Research indicates…

- Supporting evidence shows…

- As [Author] demonstrates…

- For example,…

- A study in 2022 found…

- This argument is supported by…

- A key report on this topic uncovered…

Read Also: 6 Best Ways to Provide Evidence in an Essay

Examples of Transitions to Evidence (in Context)

1. For example…

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. For example, a 2021 literature review found that 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

2. As [Author] demonstrates…

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. As Lynas et al. (2021) demonstrate, 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

3. Evidence suggests…

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. Evidence from a 2021 literature review suggests that 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

4. A study in 2021 found…

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. A study in 2021 found that 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

5. This argument is supported by…

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. This argument is supported by a comprehensive literature review in 2021 that found that 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021).”

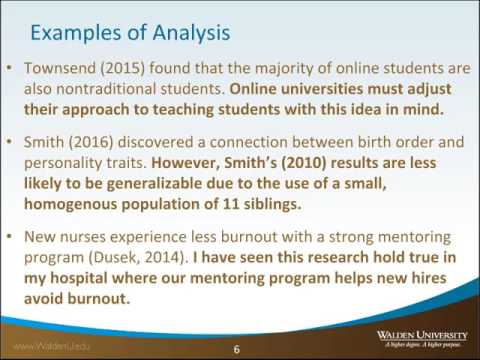

Transition Words for Explaining Evidence

After you have provided your evidence, it is recommended that you provide a follow-up sentence explaining the evidence, its strength, and its relevance to the reader .

In other words, you may need a subsequent transition word that moves your reader from evidence to explanation.

Some examples of transition words for explaining evidence include:

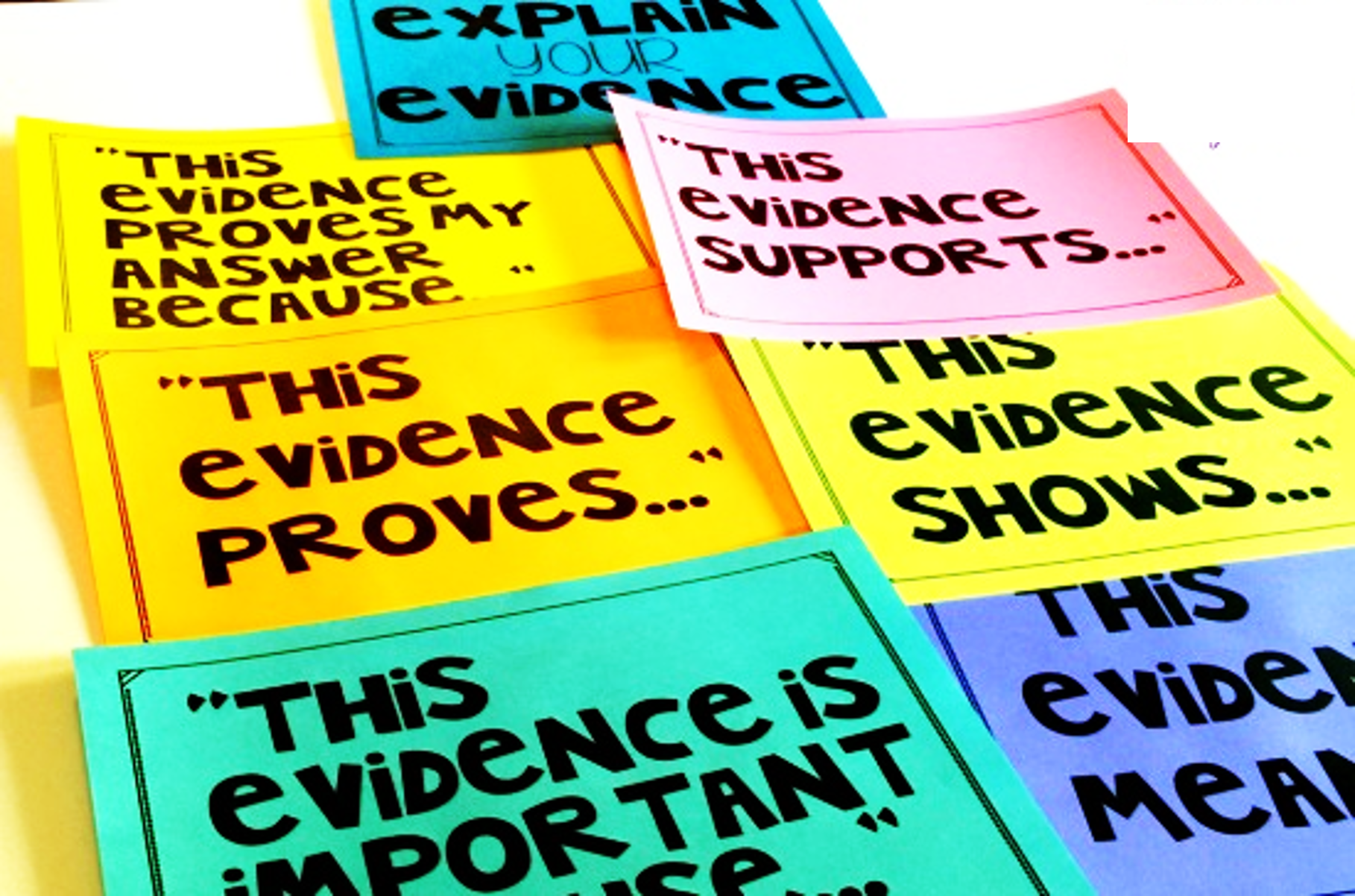

- “This evidence shows…”

- “As shown above,”

- “The relevance of this point is”

- “These findings demonstrate”

- “This evidence compellingly demonstrates”

- “These findings suggest”

- “With this information, it is reasonable to conclude”

Examples of Transition Words for Explaining Evidence (in Context)

1. “This evidence shows…”

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. As Lynas et al. (2021) demonstrate, 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021). This evidence shows that governments should take climate change very seriously.”

2. “As shown above,”

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. As Lynas et al. (2021) demonstrate, 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021). As shown above, the evidence is compelling. Governments should take climate change very seriously.”

3. “The relevance of this point is”

“ The scientific community is nearly unanimous about the human-caused impacts of climate change. As Lynas et al. (2021) demonstrate, 99% of published scientific papers on climate change agree that humans have caused climate change (Lynas et al, 2021). The relevance of this point is that the time for debate is over. Governments should take climate change very seriously.”

Writing your Paragraph

I have a very simple structure for paragraphs. It’s as follows:

- Aim for 4 to 6 sentences per paragraph

- Use a topic sentence for the first sentence

- Follow up with transition phrases that help link the topic sentence to evidence and explanations that support your topic sentence.

Sometimes people call this the TEEL paragraph: topic, evidence, explanation, linking sentence.

It looks something like this:

For more on how I teach paragraphs, watch my YouTube video below:

(You can also take my essay writing course for all my tips and tricks on essay writing!)

Other Types of Transition Words

1. Emphasis

- “This strongly suggests”

- “To highlight the seriousness of this,”

- “To emphasize this point,”

2. Addition

- “In addition,”

- “Furthermore,”

- “Moreover,”

- “Additionally,”

3. Compare and Contrast

- “By contrast,”

- “However, other evidence contradicts this.”

- “Despite this,”

Go Deeper: Compare and Contrast Essay Examples

- “Firstly”, “secondly”, “thirdly”

- “Following on from the above point,”

- “Next”, “Then”, “Finally”

5. Cause and Effect

- “As a result,”

- “This has caused…”

- “Consequently,”

- “Because of this,”

- “Due to this,”

- “The result of this”

7. Illustration and examples

- “For example,”

- “To illustrate this point,”

- “An illustrative example is…”

8. Transitioning to conclusions

- “In conclusion”

- “This essay has demonstrated”

- “Given the compelling evidence presented in this essay,”

How many are Too many Transition Words?

I generally recommend between 1 and 3 transition words per paragraph, with an average of about 2.

If you have a transition word at the start of each and every sentence, the technique becomes repetitive and loses its value.

While you should use a transition whenever you feel it is necessary and natural, it’s worth checking if you’ve over-used certain words and phrases throughout your essay.

I’ve found the best way to see if your writing has started to sound unnatural is to read it out loud to yourself.

In this process, consider:

- Removing some Transition Words: If you identify a paragraph that has a transition word at the beginning of every single sentence, remove a few so you have one at the start of the paragraph and one in the middle of the paragraph – that’s all.

- Removing Overused Words: People tend to get a single word stuck in their head and they use it over and over again. If you identify overuse of a single word, it’s best to change it up. Consider some synonyms (like some of the words and phrases listed above) to add some more variety to your language.

Related: List of Words to Start a Paragraph

Overall, transition words that show evidence can help guide your reader. They allow you to tell a smooth and logical story. They can enhance the quality of your writing and help demonstrate your command of the topic.

When transitioning from an orientation sentence to your evidence, use transition words like “For example,” and “Evidence demonstrates” to link the two sentences or paragraphs.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Green Flags in a Relationship

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Signs you're Burnt Out, Not Lazy

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Toxic Things Parents Say to their Children

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Red Flags Early in a Relationship

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Legal Matters

- Contracts and Legal Agreements

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay

Last Updated: May 5, 2024

This article was co-authored by Tristen Bonacci . Tristen Bonacci is a Licensed English Teacher with more than 20 years of experience. Tristen has taught in both the United States and overseas. She specializes in teaching in a secondary education environment and sharing wisdom with others, no matter the environment. Tristen holds a BA in English Literature from The University of Colorado and an MEd from The University of Phoenix. This article has been viewed 242,071 times.

When well integrated into your argument, evidence helps prove that you've done your research and thought critically about your topic. But what's the best way to introduce evidence so it feels seamless and has the highest impact? There are actually quite a few effective strategies you can use, and we've rounded up the best ones for you here. Try some of the tips below to introduce evidence in your essay and make a persuasive argument.

Things You Should Know

- "According to..."

- "The text says..."

- "Researchers have learned..."

- "For example..."

- "[Author's name] writes..."

Setting up the Evidence

- You can use 1-2 sentences to set up the evidence, if needed, but usually more concise you are, the better.

- For example, you may make an argument like, “Desire is a complicated, confusing emotion that causes pain to others.”

- Or you may make an assertion like, “The treatment of addiction must consider root cause issues like mental health and poor living conditions.”

- For example, you may write, “The novel explores the theme of adolescent love and desire.”

- Or you may write, “Many studies show that addiction is a mental health issue.”

Putting in the Evidence

- For example, you may use an introductory clause like, “According to Anne Carson…”, "In the following chart...," “The author states…," "The survey shows...." or “The study argues…”

- Place a comma after the introductory clause if you are using a quote. For example, “According to Anne Carson, ‘Desire is no light thing" or "The study notes, 'levels of addiction rise as levels of poverty and homelessness also rise.'"

- A list of introductory clauses can be found here: https://student.unsw.edu.au/introducing-quotations-and-paraphrases .

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back…’”

- Or you may write, "The study charts the rise in addiction levels, concluding: 'There is a higher level of addiction in specific areas of the United States.'"

- For example, you may write, “Carson views events as inevitable, as man moving through time like “a harpoon,” much like the fates of her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The chart indicates the rising levels of addiction in young people, an "epidemic" that shows no sign of slowing down."

- For example, you may write in the first mention, “In Anne Carson’s The Autobiography of Red , the color red signifies desire, love, and monstrosity.” Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review...".

- After the first mention, you can write, “Carson states…” or “The study explores…”.

- If you are citing the author’s name in-text as part of your citation style, you do not need to note their name in the text. You can just use the quote and then place the citation at the end.

- If you are paraphrasing a source, you may still use quotation marks around any text you are lifting directly from the source.

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, the characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48).”

- Or you may write, "Based on the data in the graph below, the study shows the 'intersection between opioid addiction and income' (Branson, 10)."

- If you are using footnotes or endnotes, make sure you use the appropriate citation for each piece of evidence you place in your essay.

- You may also mention the title of the work or source you are paraphrasing or summarizing and the author's name in the paraphrase or summary.

- For example, you may write a paraphrase like, "As noted in various studies, the correlation between addiction and mental illness is often ignored by medical health professionals (Deder, 10)."

- Or you may write a summary like, " The Autobiography of Red is an exploration of desire and love between strange beings, what critics have called a hybrid work that combines ancient meter with modern language (Zambreno, 15)."

- The only time you should place 2 pieces of evidence together is when you want to directly compare 2 short quotes (each less than 1 line long).

- Your analysis should then include a complete compare and contrast of the 2 quotes to show you have thought critically about them both.

Analyzing the Evidence

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48). The connection between Geryon and Herakles is intimate and gentle, a love that connects the two characters in a physical and emotional way.”

- Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review, the data shows a 50% rise in addiction levels in specific areas across the United States. The study illustrates a clear connection between addiction levels and communities where income falls below the poverty line and there is a housing shortage or crisis."

- For example, you may write, “Carson’s treatment of the relationship between Geryon and Herakles can be linked back to her approach to desire as a whole in the novel, which acts as both a catalyst and an impediment for her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The survey conducted by Dr. Paula Bronson, accompanied by a detailed academic dissertation, supports the argument that addiction is not a stand alone issue that can be addressed in isolation."

- For example, you may write, “The value of love between two people is not romanticized, but it is still considered essential, similar to the feeling of belonging, another key theme in the novel.”

- Or you may write, "There is clearly a need to reassess the current thinking around addiction and mental illness so the health and sciences community can better study these pressing issues."

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ Tristen Bonacci. Licensed English Teacher. Expert Interview. 21 December 2021.

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/quoliterature/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/evidence/

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/using-evidence.html

About This Article

Before you introduce evidence into your essay, begin the paragraph with a topic sentence. This sentence should give the reader an overview of the point you’ll be arguing or making with the evidence. When you get to citing the evidence, begin the sentence with a clause like, “The study finds” or “According to Anne Carson.” You can also include a short quotation in the middle of a sentence without introducing it with a clause. Remember to introduce the author’s first and last name when you use the evidence for the first time. Afterwards, you can just mention their last name. Once you’ve presented the evidence, take time to explain in your own words how it backs up the point you’re making. For tips on how to reference your evidence correctly, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Apr 15, 2022

Did this article help you?

Mar 2, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Unit 4: Fundamentals of Academic Essay Writing

30 Steps for Integrating Evidence

A step-by-step guide for including your “voice”.

To integrate evidence, you need to introduce it, paraphrase (or quote in special circumstances), and then connect the evidence to the topic sentence. Below are the steps for “ICE” or the “hamburger analogy.”

Step 1 Introducing evidence: the top bun or “I”

A sentence of introduction before the paraphrase helps the reader know what evidence will follow. You want to provide a preview for the reader of what outside support you will use.

- Example from the model essay: (“I”/top bun) Peer review can increase a student’s interest and confidence in writing. (“C”/meat) Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94).

- Notice how the introduction of increasing interest and confidence provides a hint of the evidence that will follow; it links to the idea of becoming a more independent and engaged learner.

Step 2 Paraphrasing and citing evidence: the meat or “C”

Typically, in academic writing, you will not simply paraphrase a single sentence; instead, you will often summarize information from more than one sentence – you will read a section of text, such as a part of a paragraph, a whole paragraph, or even more than one paragraph, and you will extract and synthesize information from what you have read. This means you will summarize that information and cite it.

Paraphrase/summarize the evidence and then include a citation with the following information (A more detailed explanation of documentation, including citations, can be found in Unit 44: Documentation.

- The author’s last name (but if you do not know the author’s name, use the article title).

- The publication date.

- The page number.

Formats for introducing evidence (when you know the author)

- Gambino (2015) explains how social networks help foster personal connections (p. 1).

- According to Gambino (2015), social networks help foster personal connections (p. 1).

- Social networks help foster personal connections (Gambino, 2015, p. 1).

Formats for introducing evidence (when you the author is unknown)

- Several tips for college success are explained (“Preparing for College,” 2015, p. 2).

- Example from the model essay: Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94).

- Here we can see a paraphrase, not a direct quotation, with proper citation format.

Step 3 Connecting evidence: the bottom bun or “E”

In this step, you must explain the significance of the evidence and how it relates to your topic sentence or to previously mentioned information in the paragraph or essay. This connecting explanation could be one or more sentences. This “bottom bun” is NOT a paraphrase; instead, it is your explanation of why you chose the evidence and how it supports your own ideas.

- Example from the model essay: (“I”/top bun) Peer review can increase a student’s interest and confidence in writing . (“C”/meat) Rather than relying on the teacher, the student is actively involved in the writing process (Bijami et al., 2013, p. 94) . (“E”/bottom bun) As students take more responsibility for their writing, from developing their topic to writing drafts, they become more confident and inspired .

- Notice how the “E” or “bottom bun” elaborates on the idea of becoming an independent learner.

Step 3 Strategies : Questions to ask yourself when analyzing the function of evidence

What “move” is the “E” / bottom bun is making? (e.g. What’s the “function” of the “E” / bottom bun?”)

- Is it interpreting the evidence?

- Is it analyzing the evidence?

- Is it describing an outcome?

- Is it providing an example?

- Is it making a prediction?

- Is it evaluating the evidence?

- Is it challenging the evidence?

- Is it elaborating on evidence that came before in the paragraph/essay?

- Is it comparing the evidence with something else or another piece of evidence?

- Is it connecting the evidence to a previously stated idea in the paragraph/essay?

Choose a function: Evaluate, Compare, Analyze, Connect, Predict

Watch this video: Evidence & Citations

Watch this video on the importance of explaining your evidence and including citations.

From: Ariel Bassett

Language Stems for Integrating Evidence

The sentence stems below can help you develop your command of more complex academic language.

Stems to refer to outside knowledge and/or experts

- It is / has been believed that…

- Researchers have noted that…

- Experts point out that…

- Based on these figures… / These figures show… / The data (seems to) suggest(s)…

Stems for introducing example evidence

- X (year) illustrates this point with an example about… (p. #).

- One of example is…. (X, year, p. #).

- As an example of this/___, ….. (X, year, p. #)

- …. is an illustration / example of… (citation).

- For example, …or For instance, …

Stems to support arguments and claims

- According to X (year), …. (p. #).

- As proof of this, X (year) claims…. (p. #).

- X (year) provides evidence for/that… (p. #).

- X (year) demonstrates that… (p. #).

Stems to draw conclusions (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- This suggests / demonstrates / indicates / shows / illustrates…

(In the above examples, you can combine the demonstrative pronoun “this” with a noun. Ex: “these results suggests…” or “this example illustrates…” or “these advantages show….”)

- This means…

- In this way,…

- It is possible that…

- Such evidence seems to suggest… / Such evidence suggests…

Stems to agree with a source (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- As X correctly notes…

- As X rightly observes, …

- As X insightfully points out, …

Stems to disagree with a source (helpful to use in the explanation / bottom bun)

- Although X contends that…

- However, it remains unclear whether…

- Critics are quick to point out that…

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay: Step-by-Step Guide

Table of contents

- 1 What Is Evidence in an Essay?

- 2.1 Testimonial

- 2.2 Anecdotal

- 2.3 Textual

- 2.4 Logical

- 2.5 Statistical

- 2.6 Analogical

- 3 How Can I Introduce Evidence in an Essay?

- 4 Key Phrases for Introducing Evidence

- 5 Dos and Don’ts in Integrating Evidence Into the Essay

What Is Evidence in an Essay?

If you want to learn how to introduce evidence in an essay, you have come to the right place. We promise to list all the essential things you need to be familiar with in order to compose an ideal academic essay . But before we turn to this particular topic, we would like to first discuss the essence of this term. Introducing evidence in an essay is a way of providing reliable and credible support for the argument or point of view taken. Professional paper writers understand that it is essential to use the right kind of evidence to back up a claim. This helps to make the argument more convincing and strengthens its validity.

Evidence forms the strongest foundation on which your essay statements can stand. It is absolutely important that every writer backs up his or her arguments with quotes, diagrams, tables, paraphrases from reliable sources, and so on. If they are not present in a text, readers are unlikely to consider the work in question professional.

Various Types of Evidence

To learn how to introduce your evidence in an essay, you should first get familiar with the different proof categories. All of them can be highly beneficial for supporting your ideas in an assignment. Although you can use an essay writing service , we believe it will be very helpful if you get familiar with the different categories. We guarantee that after reading the following sections, you will find it much easier to introduce evidence into your essay.

Testimonial

To make your academic paper even more reliable, you should consider listing the opinion of one or more experts in the particular field you are focusing on. An example of an experienced individual would be someone who has a degree in the field in question. Integrating evidence through testimonials will make your work look very professional and credible.

Another reasonable way to introduce evidence in an essay is to describe real-life experiences. Readers usually find these very intriguing, and many authors try to capture readers’ interest by including a series of personal stories or case studies. It is not a good idea to use anecdotal evidence alone, as it is not as reliable as the other options listed in this section.

This particular type is widely used and is considered one of the most useful ones when it comes to poetry analysis, for example. You can support your claims by adding quotes from books, poems, reports, and so on. Once you learn how to introduce evidence in an essay via textual references, you will find it easier to introduce the other types of evidence discussed here.

In contrast to the one listed above, logical evidence is often said to be the weakest option when it comes to supporting one’s ideas. When you choose to support an argument with logic, you are essentially presenting a hypothetical conclusion. Authors should always support their beliefs with other things, such as case studies, quotes, diagrams, etc.

Statistical

This is definitely one of the most commonly used types of support. In the simplest terms, this particular variant relies on statistics. It shows that the author has done his best to gather data from various sources. Moreover, such numerical charts or tables are quite hard to refute. They are usually presented at the beginning of an essay in order to attract the reader’s attention from the very beginning. Those are commonly used in the process of writing an academic essay, which is quite understandable, considering how useful and informative they can be.

Analogies are a great way to introduce your views on a particular topic. Incorporating evidence using comparisons is a common practice, and many authors believe it works wonders. Simply put, a writer explains his or her concepts by comparing two similar objects or situations. It is best to choose an object that is already familiar to the reader. This way, it will be easier for him to understand your arguments.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

How Can I Introduce Evidence in an Essay?

One of the most important things you should do when writing classification essays or any other type of paper, you should first create a plan you will stick to throughout the entire time. One of the essential things you should consider is how to present evidence in an essay. Here is our step-by-step guide on introducing evidence that will be of great help to you.

- Introduce the topic of your essay to readers.

- Use an argument and introduce your evidence by mentioning the name of the writer and the respective work of his.

- Citing evidence should never begin with a quote. Instead, be sure to use words or phrases such as according to, as cited by, as [author’s name] says in his book, and so on.

- When you introduce a textual reference in your essay, be sure to reproduce all quotations verbatim and put them in quotation marks.

- Right after introducing evidence to your paper, provide further information about it.

- Elaborate on why you have decided to use this book, article, statistics, or poem as a reference.

- Sum up the paragraph with a sentence that will conclude your idea.

Key Phrases for Introducing Evidence

To learn how to state evidence in an essay, you should familiarize yourself with a few key phrases that should always be present in an academic paper. As mentioned earlier, a writer should never begin directly with a citation. Regardless of whether you work on diagnostic essay writing or poetry analysis, you should always introduce your sources with the help of special phrases. Here are some of them:

As [author’s name] indicated in his study…

As stated by the author…

In accordance with what the poet says in his work…

According to the writer…

As mentioned in the book…

This particular source makes it clear that…

The writer claims that…

As shown in the statistics…

This research shows that…

For example,…

As can be seen on page 18, the writer claims that…

As he points out in his study…

Dos and Don’ts in Integrating Evidence Into the Essay

We hope that you already know the answer to the question: How do you present evidence in an essay? Nevertheless, we thought it would be best to go over the most important aspects writers should consider when they introduce their ideas using citations, diagrams, etc. Additionally, if you are in a rush and need a paper written quickly, there are many last-minute paper writing services available to help you.

First and foremost, you should never introduce your evidence with a quote, as we have already mentioned. Make sure that you use enough important introductory phrases in your analysis. Also, when writing essays, make sure that you are very familiar with the topic at hand. This way, you will have no trouble elaborating on the research papers, books, or articles you use to support your beliefs.

Moreover, it is important to edit your paper online for any mistakes or inconsistencies. This way, you can ensure that your essay is free of errors and reads smoothly. Additionally, online editing tools can help you to accurately cite any sources you use, giving your essay an extra layer of credibility.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Reading Skills

Using textual evidence to support claims.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: November 1, 2023

What We Review

Introduction

When you’re making your point in an essay or a class debate, it’s super important to back it up with evidence from the text you’re discussing. Think of it like showing your work in math class; without that step, you’re just sharing an opinion that might not seem well-founded.

It’s not the most exciting thing to search for text evidence to incorporate into your writing. It takes work! Digging to find the right evidence, integrating it, citing it correctly, and explaining how it ultimately supports your claim is no simple task.

However, this process is an immensely powerful exercise in teaching students how to become effective communicators. High school is all about learning to juggle different kinds of reading – stories, factual articles, you name it – and making strong points about them. And this isn’t just for getting good grades. This skill will follow you to college and even to your future job, where being able to back up your ideas with solid facts will really matter.

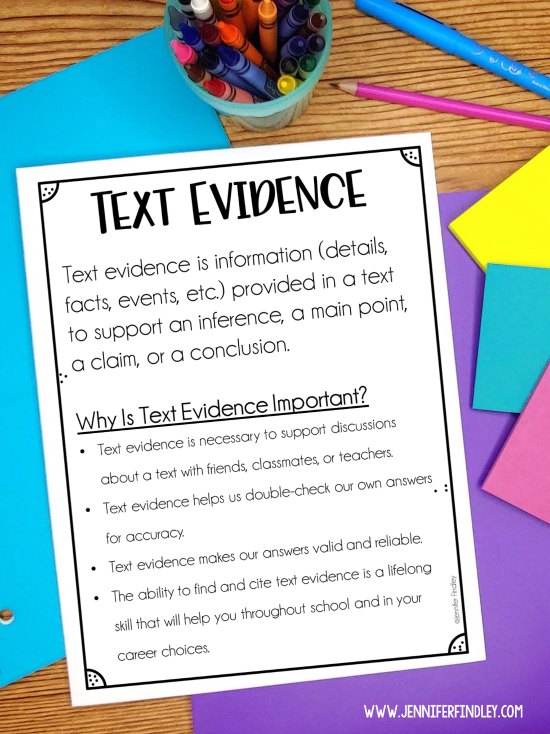

What is Textual Evidence?

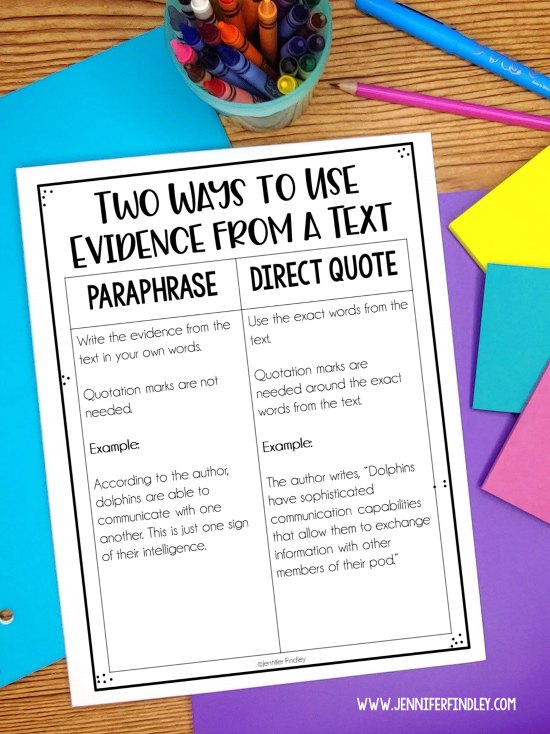

Alright, let’s break it down: What’s this thing called textual evidence? It’s pretty much any part of a book or article that you use to back up your points. It could be an exact line taken straight from the text (a direct quote), your own version of what the author said (a paraphrase), or even a boiled-down version of a big section (a summary). No matter how you slice it, the goal is the same: to support your argument.

In high school, you’ll often be asked to dig deep into books and write a literary analysis. This is just a fancy way of looking closely at a particular piece of the book, like the theme or how the characters change over time. Take, for example, if you’re asked to write about how Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird deals with racial discrimination.

You’d go on a sort of scavenger hunt through the novel, hunting for every bit that shows racial discrimination. Then, in your essay, you’ll bring out these examples to back up your point. Like, you might sum up the trial of Tom Robinson to show that even though there wasn’t enough evidence to prove he did anything wrong, he was still convicted. That’s a powerful piece of textual evidence to help explain the book’s message about the unfairness of racial prejudice.

Identifying Textual Evidence

Now let’s figure out how to spot the right textual evidence. When you need to back up your points, picking the right evidence from the text can be tricky. If you closely read the text, you’ll be in a way better position to choose the strongest evidence for your argument.

So, you’ve read closely and marked up the text with notes and highlights. When it’s time to write your essay, these annotations are like a treasure map. You don’t have to reread everything; just skim through your notes to see which bits connect to your point. Find a section that fits with what you’re saying? Great—now decide how to use it best in your essay. Sometimes you’ll use the exact words (a direct quote), and other times you’ll put it in your own words (paraphrase).

Let’s say you’re looking at “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and you note where the Black community sits during Tom Robinson’s trial—in a separate balcony. This detail doesn’t come from someone’s mouth, but it’s a powerful snapshot of racial segregation, so you don’t need to quote anyone. On the flip side, when Atticus Finch nails it with his speech about the false belief that all Black people are not to be trusted, his exact words are gold. They directly show the theme of racial discrimination, so you’d definitely quote him directly in your essay.

Evaluating Textual Evidence

When you’re writing an essay for English class, you know the books and stories you study are solid sources. But what about when you’re on your own, searching online for that perfect piece of evidence to make your essay shine? It’s not always easy to know if what you find on the internet is reliable. Here’s a quick guide to judge if an online source is up to the mark:

- Who Wrote It: Check out who’s behind the article or webpage. What’s their background or education? Are they an expert? This matters because you want info from people who are trusted in their field.

- Fact-Check: Look at the info you find and cross-check it with other sources. If a website claims “To Kill a Mockingbird” is about how to catch birds, that’s a red flag—it’s way off from the book’s actual content.

- Look for Citations: Good authors back up their points with evidence, just like you’re doing in your essays. If the webpage or article lists its sources, that’s a sign the author has done their homework.

- Watch for Bias: It’s okay for sources to have a point of view , but you should know what that bias is. Understanding an author’s perspective helps you consider how their opinion might shape the information they present.

- Freshness: How recent is the information? Check when the article was written or last updated. While the latest isn’t always the greatest, especially for classic literature, it’s still good to know if the information is current.

Remember, picking the right evidence isn’t just about filling in quotes—it’s about building a case that what you’re saying is legit. And that means being choosy about where you get your facts from, especially online.

Incorporating Textual Evidence into Analysis

Got your claim and your evidence lined up? Great, now let’s talk about how to weave that into your essay without it sounding like a jumbled mess. Kick things off with a clear thesis statement. This is where you lay out your main argument and hint at how you will prove it.

Now, when chatting with friends, you probably introduce cool facts or stories with a casual “Hey, did you know…” or “For instance…” Use that same approach in your essay. Phrases like “For example” or “As [this character] states in the text…” are your friends here. They help you slide your evidence into your essay smoothly.

Don’t forget about those punctuation marks when you’re using direct quotes; they’re like traffic signals for your reader, so they don’t get lost. And whether you’re quoting directly, paraphrasing, or summarizing, always pop an in-text citation in there to give credit where it’s due. It’s like saying, “Hey, don’t just take my word for it; here’s where I got it from.”

Finally, don’t just drop a quote and run. Follow it up with a clear explanation. This is where you tie your evidence back to your claim, showing how it backs up your argument. Think of it as the grand finale of your evidence presentation—it makes your case convincing.

Textual Evidence in Action: Dissecting Discrimination in To Kill a Mockingbird

Below is an example from an essay on racial discrimination in To Kill a Mockingbird that uses these conventions.

“In Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, the theme of racial discrimination is revealed through the events of Tom Robinson’s trial, from the threats he received at the jail, to Atticus’ charge to the jury, and finally, in the trial’s unjust verdict. For example, in Chapter 15, Tom Robinson is being held at the local jail, and Atticus Finch takes it upon himself to guard Tom’s cell. Finch’s decision is not unwarranted, as several cars pulled up to the jail, men got out of their cars, and these men surrounded Atticus (Lee 127). Finch knew that these men racially discriminated against Tom and intended violence against him as a Black man, and Finch was determined to protect Tom and ensure that Tom was granted a chance at a fair trial.”

Common Pitfalls and Mistakes

When it comes to writing a killer literary analysis, there are a few traps students tend to fall into. For starters, getting citations wrong or skipping them altogether is a big no-no. Luckily, resources like the Purdue OWL website are there to help you nail the citation game.

Another slip-up is making your evidence say too much or too little. Imagine saying, “Some mad guys chatted with Atticus at the jail and bounced.” That’s way too vague and doesn’t do the job of explaining how it supports your point. Plus, it kind of twists what actually happened in “To Kill a Mockingbird”.

Picking evidence that doesn’t fit your claim is another common blunder. Say you’re talking about racism, and you bring up how the people of Maycomb don’t trust the Ewells. If you’re using that to show racial discrimination, you’re off track because their mistrust is about the Ewells’ nasty reputation, not their race.

What is the best way to sidestep these errors? Make sure you really get the text. That means reading closely and carefully so that when it’s time to write, you choose the best bits of the book that really back up your argument.

Wrapping it up, when you’re making a point about what you’ve read, it’s crucial to back it up with solid text evidence. You’ve got to be on the ball with picking out the right parts of the text, judging which online sources are legit, and mixing your evidence into your argument just right. Learning to stand up for your ideas with clear writing and confident talking is a game-changer. It’s all about getting your point across with evidence that packs a punch. That’s how you go from just saying something to really proving it—and that’s a skill that’ll take you places – in school and beyond.

Practice Makes Perfect

To truly hone your skills in analyzing and supporting arguments with textual evidence, regular practice is key—and that’s where Albert comes into play. It’s not just about reading; it’s about engaging with a range of texts to sharpen your analytical tools.

If you’re just starting out, our Short Readings course is ideal. It uses brief passages to solidify those vital reading skills.

Another option for practice is our Leveled Readings course, where you’ll find a range of Lexile® leveled passages that all revolve around essential questions. This ensures that everyone is engaged, no matter their reading level. Click here for more information about the Lexile® framework!

Albert.io isn’t just about the practice—it’s about practicing smart. With a user-friendly interface and feedback that actually teaches you something, it’s your go-to for mastering close reading and getting to grips with complex texts. When it comes to backing up your points with the right evidence, you’ll be doing it with confidence and flair.

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

We’re reviewing our resources this spring (May-August 2024). We will do our best to minimize disruption, but you might notice changes over the next few months as we correct errors & delete redundant resources.

Integrating Evidence Effectively

Let’s say you’ve identified some good evidence for an argument in your paper. You’ve already decided to keep the evidence as a direct quote or to paraphrase the information you found. Or maybe your evidence is a table or graph. But what’s the next step? Where should the quotation, paraphrase, or other evidence go in the paragraph? And how do you include it without everything looking choppy, or even worse, confusing?

Integrating evidence smoothly into your writing requires a few standard tools plus some critical thinking. You can think of the process in three stages: signaling , situating , and synthesizing .

Let your reader know when a quote or paraphrase is coming. Doing so helps your readers distinguish between what thoughts are your own and what information or commentary is from another author.

Signaling involves two components: an attribution (the author’s name and/or title of the text) and a signal verb .

The choice of signal verb is important because it tells the reader what you think about the source text being paraphrased. Consider, for example, the difference between alleges and affirms . Alleges casts doubt on the statement, while affirms projects confidence and demonstrates agreement. For more information, see Reporting Verbs .

Author-prominent and information prominent writing styles

Academic writing requires that you integrate evidence to support your argument. However, the way you blend evidence into your own words depends on both the discipline and what kind of context it prioritizes: authorship or information. For more extensive help, see Integrating evidence effectively: author- or information-prominent citations .

Author-prominent

Cargill and O’Connor (2009) studied wheat and barley collected from the Virginia field site.

In the previous sentence, Cargill and O'Connor is the attribution and studied is the signal verb. Notice that the authors appear at the beginning of the sentence.

Information-prominent

Wheat and barley, collected from the Virginia field site, were studied (Cargill & O’Connor, 2009).

In this second example, the attribution is still the same (Cargill and O'Connor), as is the signal verb (were studied). But notice that the information (wheat and barley...) comes at the beginning of the sentence to draw the reader's focus there.

When situating evidence, you make clear to readers how the original writer presented their information. What larger argument was the writer making? Are there any additional details that may help your reader understand the information more clearly? For instance, did the author provide any exceptions or caveats to what was mentioned?

Compare the two passages below, which introduce the same quotation. Passage A provides very little context about the author Bordo’s quotation, whereas Passage B situates the quotation within Bordo’s larger argument.

Passage A: Little context

Susan Bordo writes about women and dieting. "Fiji is just one example. Until television was introduced in 1995, the islands had no reported cases of eating disorders. In 1998, three years after programs from the United States and Britain began broadcasting there, 62 percent of the girls surveyed reported dieting" (149-50).

Passage B: Situates the quotation within the context

The feminist philosopher Susan Bordo deplores Wester media's obsession with female thinness and dieting. Her basic complaint is that increasingnumbers of women across the globe are being led to see themselves as fat and in need of a diet. Citing the islands of Fiji as an example, Bordo notes that "until television was introduced in 1995, the islands had no reported cases of eating disorders. In 1998, three years after programs from the United States and Britain began broadcasting there, 62% of the girls surveyed reported dieting" (149-50).

You chose your piece of evidence because it helps support your argument, but evidence doesn’t speak for itself. Your synthesis will be the glue that holds these pieces of evidence together, showing how they support your point.

Below, you can see a sample paragraph that has been divided out into its three main parts. The final section shows how synthesizing clarifies the purpose of the evidence used.

Writer’s main argument/clai m : In June 2018, the UK introduced a new Counter-terrorism and Border Security bill, which received Royal Assent on February 12th 2019. However, several clauses are troubling. The bill suffers from vagueness and ambiguities that could inappropriately prosecute academics and journalists. It could also have a chilling effect on free speech and freedom of expression. Most notably, Clause 1 of the bill would criminalize the expression of support for a proscribed terrorist organization.

Evidence that Clause 1 would criminalize support for a proscribed terrorist : When RSF (Reporters Without Borders) briefed the government on the problematic language, they noted the lack of clarity around the word “supportive” in Clause 1, and were concerned it would stifle debate.

Synthesis : Imagine, for example, a conversation between two academics on the ideologies of two terrorist organizations. While both academics might condemn the actions of those groups, one of them might claim that Group A’s ideology is more legitimate than Group B’s. Would this count as expressing support for the terrorist organization? The bill does not specify.

In the synthesis , the writer explains how the vagueness of the word “supportive” could be interpreted in a variety of ways, potentially leading to condemnation of some opinions. This synthesis helps show how the evidence supports both the minor claim, and, ultimately, the author’s main argument.

27 Flow: Integrate Textual Evidence (Quotes, Paraphrases, Summaries)

Flow: integrate textual evidence (quotes, paraphrases, summaries), integrate textual evidence (quotes, paraphrases, summaries) concerns.

- your ability to weave citations into a text, to synthesize all available information, in ways that support and substantiate the text–its thesis/research question , rhetorical stance , tone .

- your ability to introduce and clarify the ethos of the quoted, paraphrased, or summarized information

- your professionalism in terms of providing the details others need to locate the sources you’re citing and affirmation that information has value.

The ability to Integrate Textual Evidence is a core 21st century literacy , whether you’re writing for the workplace or school.

When quotations are smoothly integrated, writers can strategically introduce their readers to the new speaker, connect their point to the quotation’s theme, and provide their audience with a clear sense of how the quote supports the paper’s argument. Using these tactics to segue from the writer’s voice to the source’s voice can add agency and authority to the writer’s ideas.

In workplace and school settings, texts that are judged to be substantive are typically informed by textual research.

When working to integrate textual research into your text, you want your readers to understand how the new information relates to your ideas and arguments.

Here is one example of engaging with source material in an engaging, conversational mode:

Tom Smith writes, “Most ponies enjoy skateboarding on Saturday nights” (8). Though my findings support Smith’s claims that most ponies do enjoy skateboarding, however, my research shows that ponies tend to skate on Sunday afternoons. The differences in our findings may come from the recent changes in skateboarding laws, which are not applicable on Sundays because skateboarding officials have the day off.

In this example, the writer responds to the source material by comparing and contrasting the source’s ideas with his or her own. The source material is the section of the sentence that appears between the quotation marks. This sentence comes from page 8 of Tom Smith’s book; this is indicated by the number 8 that appears between the parentheses. If the writer and Tom Smith were at a party together, their conversation would be interesting and vibrant. Here is one example of unsuccessful source engagement:

Tom Smith writes, “Most ponies enjoy skateboarding on Saturday nights” (8). I agree.

In this example, we see no engagement with the source material. If the writer and Tom Smith were talking at a party, it would be a boring conversation that does not go anywhere. Simply agreeing or disagreeing does not continue the conversation, nor does it highlight the importance of your findings. Another way of thinking about source engagement is a three-step process: explain, engage, and discuss.

- Explaining: Explaining requires that you explain what the author in the source is talking about and why it is important. Do not take it for granted that readers will know why the source material you use is important or significant.

- Engaging: The second step, engage, requires you to talk back to the source

- Discussing: Finally, discuss the implications of your response. Here is an example of this process:

Example: The latest study from Bird University found that “parrots tend to sleep all day on Sundays” (1). This finding is significant because it supports my hypothesis that Sunday is the official day of rest for parrots. Further research on this topic is necessary; it could be significant to many other fields of study if other varieties of birds also rest on Sundays.

Five Strategies for Integrating Textual Evidence

When citing outside research, writers want to

- Avoid dropped quotes

Introduce the Author’s Name and Publication

- Use a signal phrase at the beginning or end of the quotation

- Use an informative sentence to introduce the quotation

- Use appropriate signal verbs

Repeat the Author’s Name to Aid Cohesion & Comprehension When You Continue to Reference that Author

- Use Punctuation to Set off Sources from Your Prose.

Avoid Dropped Quotes

Dropped Quotes are quotes that are dropped into a text without being introduced. Readers are confused by dropped quotes, particularly when numerous quotes are dropped, because

- they don’t know enough about the source to determine if its authentic, reliable, timely.

- they cannot distinguish between what the writer is saying and what the sources are saying–i.e., who is speaking, who is driving the argument

- they cannot tell how the dropped quotes relate to one another or the writer’s thesis/research question.

Dropped quotes disrupt the flow of thought, create an abrupt change in voice, and/or leave the reader wondering why the quote is included.

Instead of creating an unwelcome disruption in their paper’s cohesiveness with a dropped quotation, thoughtful writers should employ strategies for smoothly integrating source material into their own work.

You should introduce your quotes with your own words either before or after the quote—do not ask the quote to “speak for itself” and do all the work alone—you have to explain to the reader what the quote is doing there. You can avoid dropped quotes by

- distinguishing between your ideas and those of your sources

- introducing your sources, clarifying their ethos , pathos , logos .

When incorporating a source into your paper for the first time using MLA, reference not only the author’s full name (if provided) but also the title of the publication.

If you wanted to use a quote from Homi Bhabha’s The Location of Culture and you had not referenced this source yet in your paper, you would want to give it a full introduction:

In The Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha discusses the effect of mimicry upon the cultural hybrid, claiming that mimicry renders “the colonial subject . . . a ‘partial’ presence” (123).

Before quoting, you provide the reader with both the author (Homi Bhabha) and the title of the publication (The Location of Culture). That way, going forth, unless you introduce a different book or article, the reader knows that all references to Bhabha come from The Location of Culture.

Use Signal Phrases

When using information from a source, whether just summarizing or analyzing the information, you need to indicate where that information came from. If an you do not use signal words and phrases to show where the information came from, others may assume you are presenting your original ideas. That sort of error constitutes unintentional plagiarism. When incorporating quotes, facts, evidence, and/or paraphrasing from a reference, or source, indicate where the information came from with phrases such as:

- According to the author…

- The author states…

- In the article…

- The source provides information about…

- Noted journalist John Doe proposed that “ . . . ” (14).

- “. . . ,” suggested researcher Jane Doe (1).

- Experts from The Centers for Disease Control advise citizens to “ . . . ” (CDC).

Below is an example of a source summary paragraph in which it is unclear whether the information is from the source or the author’s own ideas. In this summary, the author of the paragraph does not use signal words and phrases to link the information to the author of the research source. Click here for the original article.

Some people say that whoopee cushions originated in the Middle Ages, but they were actually invented in 1930s Canada. Whoopee cushions became popular very quickly, making appearances in a 1942 Bob Hope and Bing Crosby movie and 1950s comics. Over time, the whoopee cushion has changed from green to mostly pink in color and a wooden mouth to a rubber one. They are now made mostly in China.

Now, here is the same summary with signal words and phrases (in bold) to indicate that the information comes from a source. The author does not use a signal word or phrase for each sentence, but the author does make it clear when using information from a research source.

According to the article “Who Made That Whoopee Cushion, some people say that whoopee cushions originated in the Middle Ages, but they were actually invented in 1930s Canada. Authors Hilary Greenbaum and Dana Rubinstein describe how whoopee cushions became popular very quickly, making appearances in a 1942 Bob Hope and Bing Crosby movie and 1950s comics. The authors also state that over time, the whoopee cushion has changed from green to mostly pink in color and a wooden mouth to a rubber one. They are now made mostly in China.

Use an informative sentence to introduce the quotation:

- The results of dietician Sally Smith’s research counter the popular misconception that a vegan diet is nutritionally incomplete:

- An experiment conducted by Dave Brown indicates that texting while driving is more dangerous than previously believed:

Use appropriate signal verbs:

| adds | confirms | lists | reports |

| argues | describes | illustrates | states |

| asserts | discusses | notes | suggests |

| claims | emphasizes | observes | writes |

When incorporating a source into your paper for the second time (or any other time following the initial introduction of that source) using MLA, provide the reader with only the author’s last name.

If you are still working with Bhabha’s The Location of Culture, you might do something like this:

As Bhabha writes, “[Mimicry] is a form of colonial discourse that . . . [exists] at the crossroads of what is known and permissible and that which though known must be kept concealed” (128).

Since you’ve already provided the reader with Bhabha’s full name (Homi Bhabha), there’s no need to give it again. All later references thus only require Bhabha’s last name. If pulling material from a different work of Bhabha’s, though, you’ll need to introduce the quote (or paraphrase or summary) by specifying this new title (though you’ll still only need to provide Bhabha’s last name).

Note: Never refer to an author by his or her first name. Either reference the author by his or her full name or by his or her last name, depending upon whether or not you’ve previously mentioned the author’s full name in your piece of writing.

Use Punctuation to Set off Sources from Your Prose

In the interests of Brevity, Clutter, Concision , you may not want to cite only a few words from a source rather than a lengthy quote. Dashes, Ellipses, Parenthesis–these forms of punctuation enable you to distinguish your ideas from your sources.

You may choose to use a dash (two hyphens) or a colon to introduce the quoted material.

This can be tricky, depending upon the excerpt you’re using, because you may have to rework the wording within the quote to suit the sentence structure.

Whenever you change or add/delete anything—anything at all, even a capitalization—within a quote, you must bracket [ ] the change, addition, or deletion.

The child crosses this bar when he enters into language, as he can never again access the Real—a realm that now may “only [be] approach[ed] through language” (Price Herndl 53).

You may choose to change the wording within a quote (and bracket accordingly) so that it works within your sentence structure.

The excerpted material must make sense within the context of your sentence, and the reader still must be able to distinguish between your ideas and those of your source.

The child crosses this bar when he enters into language, as he can never again access the Real, for “[he] can only approach it through language” (Price Herndl 53).

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. Print.

Price Herndl, Diane. “The Writing Cure: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Anna O., and ‘Hysterical’ Writing.” NWSA Journal 1.1 (1988): 52–74. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 30 April 2011

Licenses and Attribution

“Flow: Integrate Textual Evidence (Quotes, Paraphrases, Summaries)” by Joseph M. Moxley is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Using Research to Support Scholarly Writing Copyright © 2021 by Matthew Bloom; Christine Jones; Cameron MacElvee; Jeffrey Sanger; and Lori Walk is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Peterborough

Effectively Integrating Evidence

- Writing about Evidence

Attribution to a Source

- Verbs of Attribution

Using Quotations as Evidence

- How to Incorporate Quotations in Paragraphs

Writing About Evidence

Your paper's success depends on your ability to provide and explain evidence. Be specific in your discussion of the evidence: accurately convey the idea, data, or example and present your interpretation and explanation of the evidence in relation to your thesis.

Remember that specific evidence is strong evidence; avoid broad generalizations or vague ideas. Offer clear examples, detailed processes, numerical data, theoretical background, or other types of evidence.

Be intentional about your use of evidence. Ask yourself a few questions:

- What piece of evidence best demonstrates the idea I develop in this paragraph?

- Do I need to summarize (focus on the main point or finding), paraphrase (explain a particular detail), or directly quote this evidence?

- What important context do I need to identify to accurately and clearly write about this evidence?

- How does this piece of evidence demonstrate the idea?

- How does this evidence fit with other pieces of evidence?

Learn more: Effective Summarizing and Paraphrasing

It is important to clearly identify the source of evidence in your writing. Of course, any evidence you use from another source must include a citation, but it is also common to make reference to a source within a sentence.

- Use the name of the author or authors. In CSE and APA format, a surname is typically used; however in MLA and Chicago, it is more usual to include a first name and surname in addition to position, if it is relevant (e.g., agricultural historian, Douglas McCalla or former Ontario premier, Bob Rae).

- Titles of books, journals, works of art, plays and movies should be italicized.

- Tiles of articles, chapters, and unpublished works should be put in quotation marks (double quotes).

Verbs of attribution