Newly Launched - AI Presentation Maker

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

AI PPT Maker

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 10 Qualitative Research Report Templates with Samples and Examples

“Research is to see what everybody else has seen, and to think what nobody else has thought, ” said Hungarian biochemist and Nobel laureate Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, who discovered Vitamin C. This fabulous statement on research as a human endeavor reminds us that execution matters, of course, but the solid pillar of research that backs it is invaluable as well.

Here’s an example to illustrate this in action.

Have you ever wondered what makes Oprah Winfrey a successful businesswoman? It's her research abilities. Oprah might not have been as successful as a news anchor and television show host if she hadn't done her exploratory research on key topics and public figures. Additionally, without the research and development that went into the internet, there was no way that you could be reading this post right now. Research is an essential tool for understanding the intricacies of many topics and advancing knowledge.

Businesses in the modern world are, increasingly, based on research. Within research too, the qualitative world of non-numerical observations, data, and impactful insights is what business owners are most interested in. This is not to say that numbers or empirical research is not important. It is, of course, one of the founding blocks of business.

In this blog, however, we focus on qualitative research PPT Templates that help you move forward and get on the profitable highway and take the best decisions for your business.

These presentation templates are 100% customizable, and editable. Use these to leave a lasting impact on your audience and get recall for your business value offering.

Top 10 Qualitative Research Report Templates

The goal of qualitative research methods is to monitor market trends and attitudes through surveys, analyses, historical research, and open-ended interviews. It helps interpret and comprehend human behavior using data. With the use of qualitative market research services, you may get access to the appropriate data that could help you make decisions.

After finishing the research portion of your assignment effectively, you'll need a captivating way to present your findings to your audience. Here, SlideTeam's qualitative research report templates come in handy. Our top ten qualitative research templates will help you effectively communicate your message. Let’s start a tour of this universe.

Template 1 : Qualitative Research Proposal Template PowerPoint Presentation Slides

For the reader to understand your research proposal, you must have well-structured PPT slides. Don't worry, SlideTeam has you covered. Our pre-made research proposal template presentation slides have no learning curve. This implies that any user may rapidly create a powerful professional research proposal presentation using our PPT slides. Download these PowerPoint slides in a way that will convince your reviewers to accept your strategy.

Download Now!

Template 2 : Qualitative Research Powerpoint PPT Template Bundles

You may have observed that some brands have taken the place of generic words for comparable products in our language. Even though we are aware that Band-Aid is a brand, we always ask for Band-Aid whenever we require a plastic bandage. The power of branding is quite astounding. This is the benefit that our next PPT template bundles will provide for your business. Potential customers will find it simpler to recognize your brand and correctly associate it with a certain good or service because of our platform-independent PowerPoint Slides. Download now!

Template 3 : Qualitative Research Interviewing Presentation Deck

Do you find it hard to handle challenging conversations at work? Then, you may conduct effective interviews employing this PowerPoint presentation. Our presentation on qualitative research interviews aimed to "give voice" to the subjects. It provides details on interviews, information, research, participant, and study methodologies. Download this PowerPoint Presentation if you need to introduce yourself effectively during a quick visual communication.

Template 4 : Thematic Analysis Qualitative Research PPT PowerPoint Presentation Outline Rules CPB

Thematic analysis is a technique used in qualitative research to arrive at hidden patterns and other inferences based on a theme. Any research can employ our Thematic analysis qualitative research PPT. By using all the features of this adaptable PPT, you may convey information well. By including the proper icons and symbols, this presentation can be improved as an instructional tool and opened on any platform. Download now!

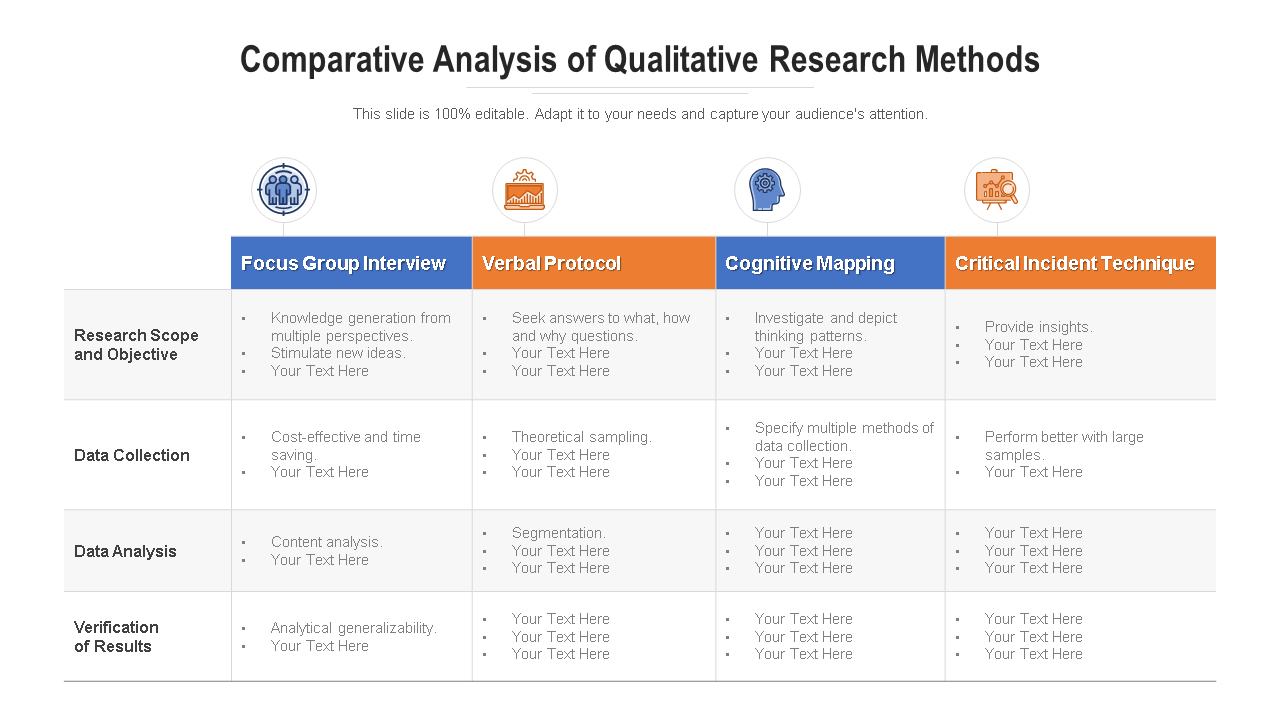

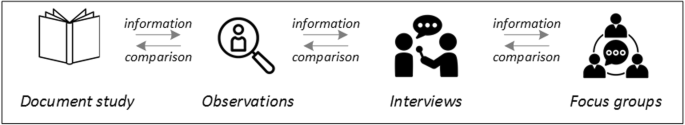

Template 5 : Comparative Analysis of Qualitative Research Methods

Conducting a successful comparison analysis is essential if you or your company wants to make sure that your decision-making process is efficient. With the help of our comparative analysis of qualitative research techniques, you can make choices that work for both your company and your clients. Focus Group Interviews, Cognitive Mapping, Critical Incident Technique, Verbal Protocol, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Research Scope, and Objective are covered in this extensive series of slides. Download today to carry out efficient business operations.

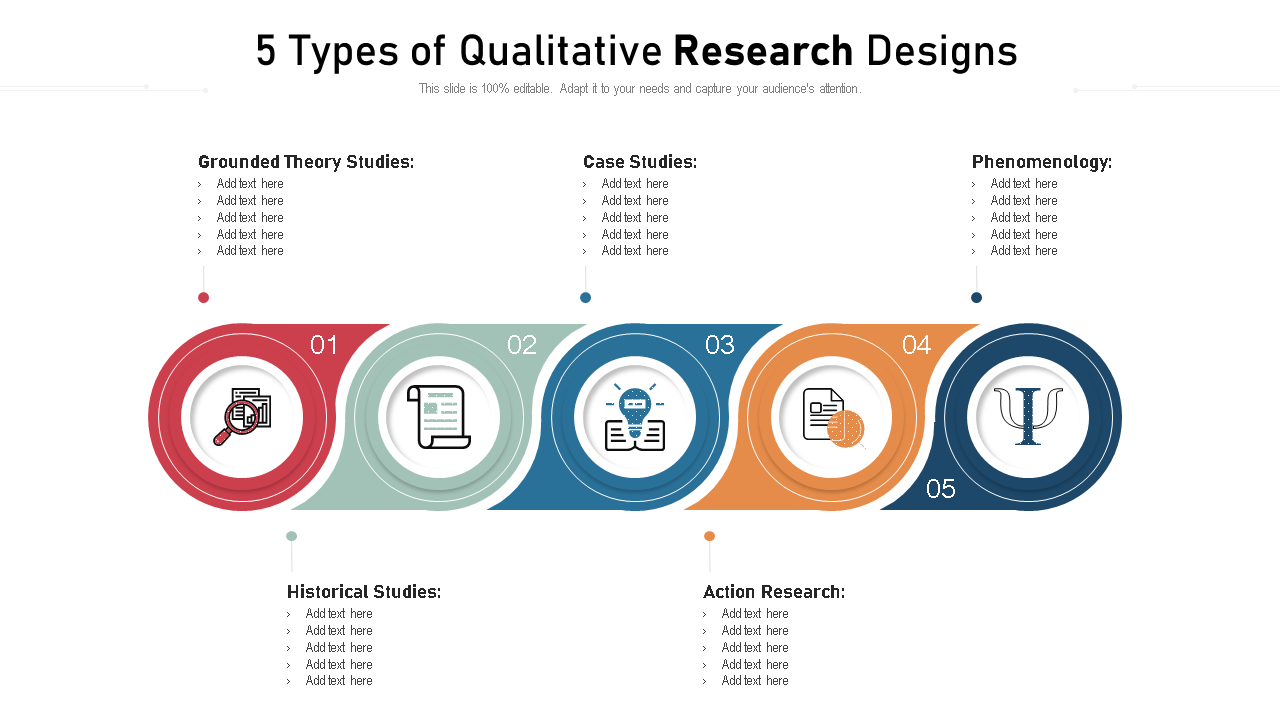

Template 6 : Five-Type of Qualitative Research Designs

Your business can achieve significant results with the help of our five qualitative research design types. Given that it incorporates layers of case studies, phenomenology, historical studies, and action research, it qualifies as a full-fledged presentation. Download this presentation template to perform an objective, open-ended technique and to carefully consider probable sources of errors.

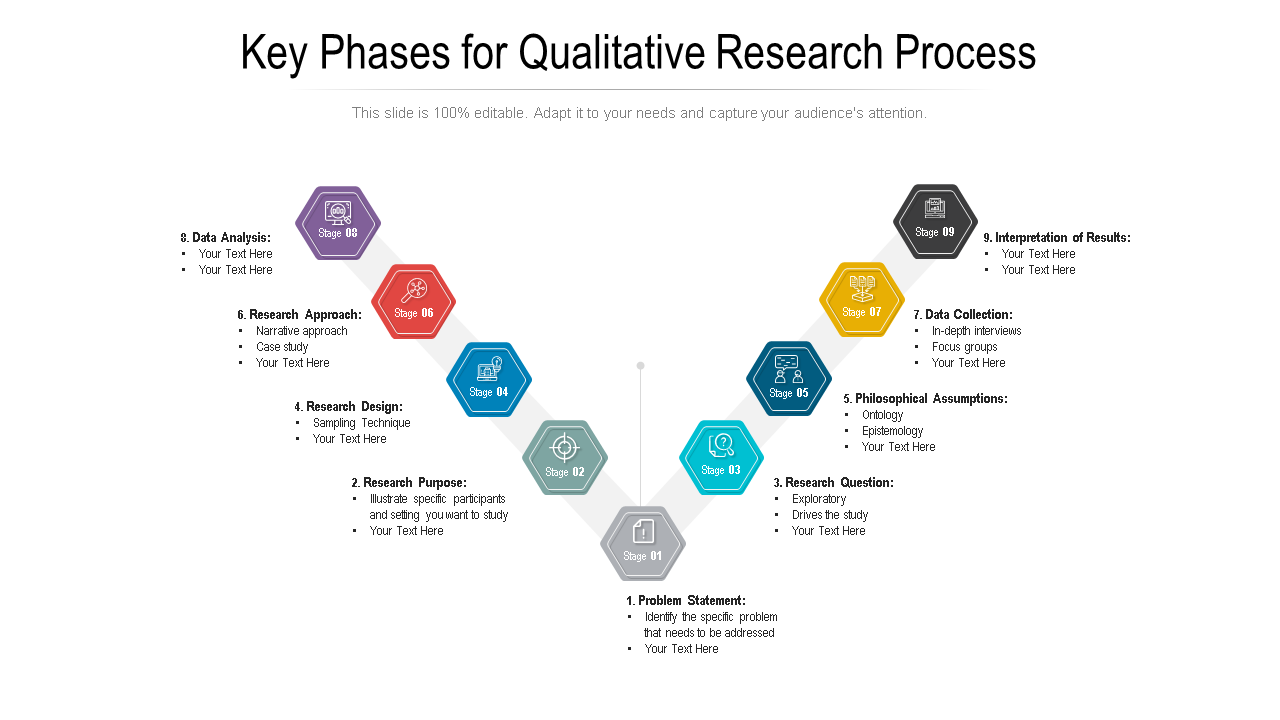

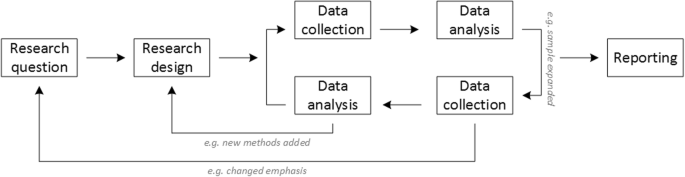

Template 7 : Key Phases for the Qualitative Research Process

Any attempt at qualitative research, no matter how small, must follow the prescribed procedures. The key stages of the qualitative research method are combined in this pre-made PPT template. This set of slides covers data analysis, research approach, research design, research aim, issue description, research questions, philosophical assumptions, data collecting, and result interpretation. Get it now.

Template 8 : Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Research Data

Thematic analysis is performed on the raw data that is acquired through focus groups, interviews, surveys, etc. We go over each and every critical step in our slides on thematic analysis of qualitative research data, including how to uncover codes, identify themes in the data, finalize topics, explore each theme, and analyze documents. This completely editable PowerPoint presentation is available for instant download.

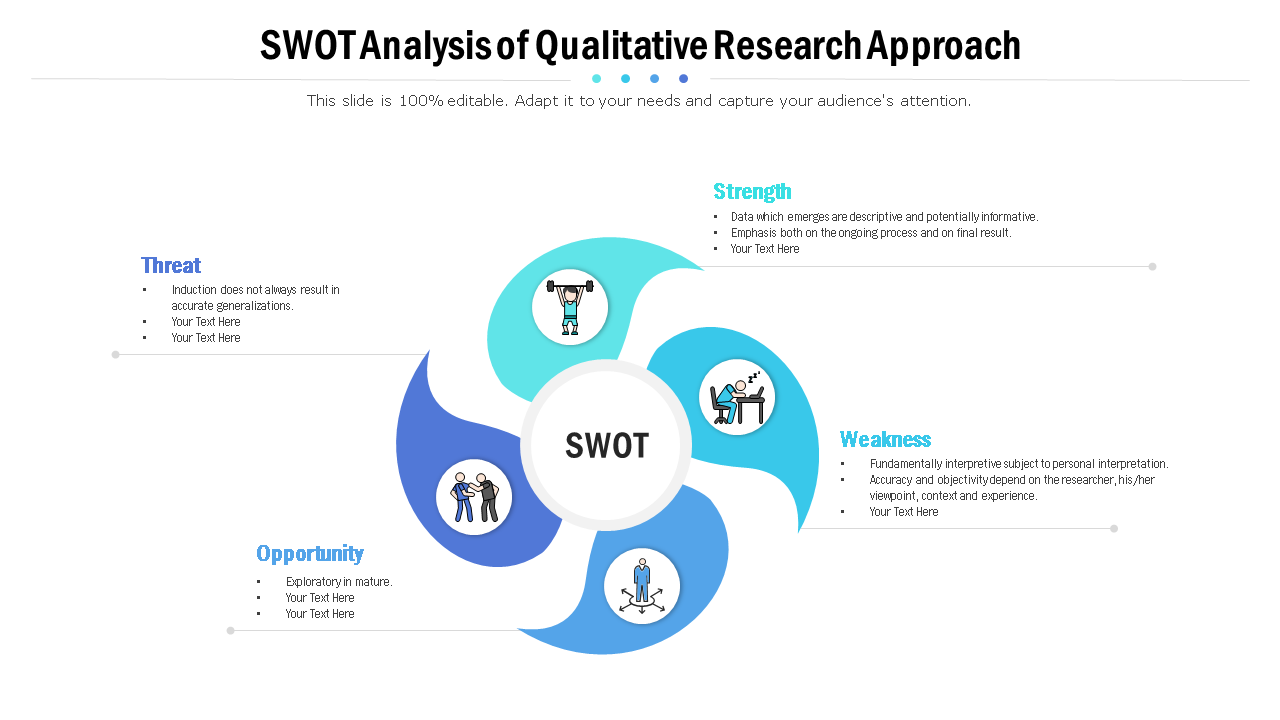

Template 9 : Swot Analysis of Qualitative Research Approach

Use this PowerPoint set to determine the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats facing your company. Each slide comes with a unique tool that may be utilized to strengthen your areas of weakness, grasp opportunities, and lessen risks. This template can be used to collect statistics, add your own information, and then begin considering how you might get better.

Download now!

Template 10 : Qualitative Research through Graph Showing Revenue Growth

A picture truly is worth a thousand words even when it comes to summarizing your research's findings. Researchers encounter an unavoidable issue when presenting qualitative study data; to address this challenge, Slide Team has created a user-responsive Graph Showing Revenue Growth template. This slideshow graph could help you make informed decisions and encourage your company's growth.

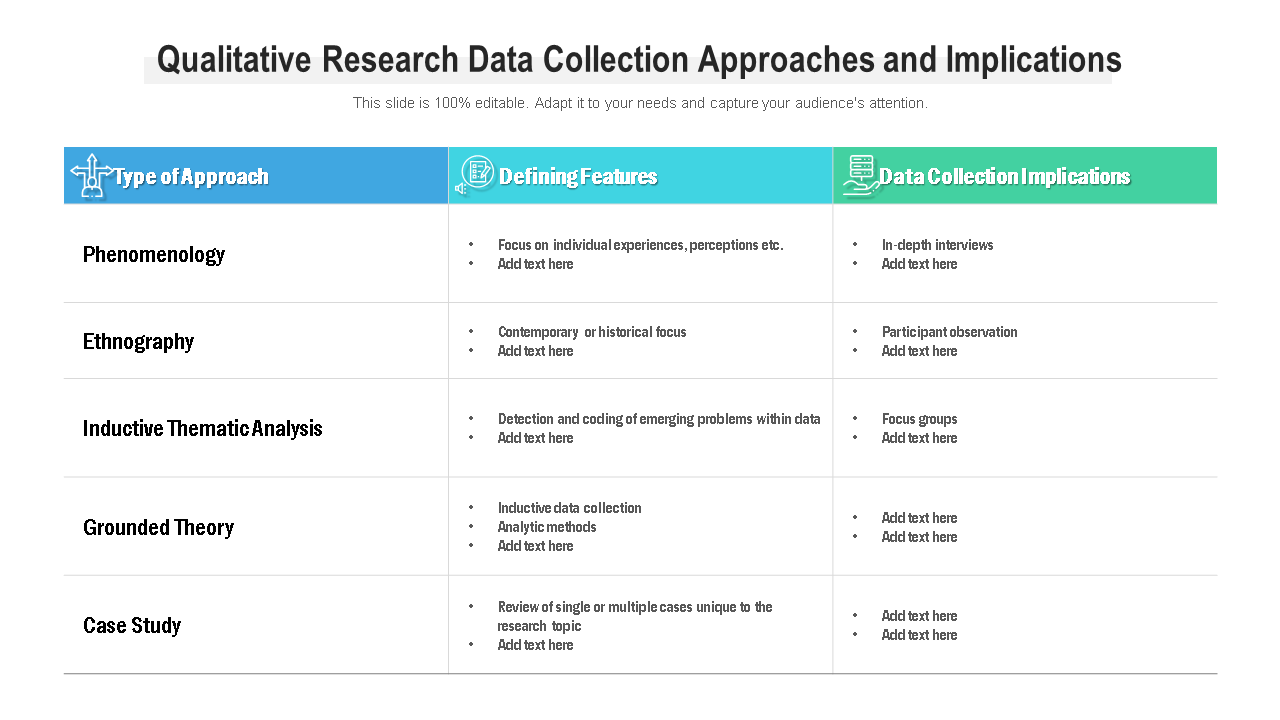

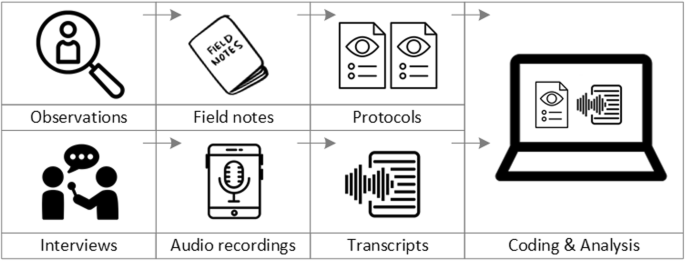

Template 11 : Qualitative Research Data Collection Approaches and Implications

Like blood moving through the circulatory system, data moves through an organization. Businesses cannot run without data. The first step in making better decisions is gathering data. This presentation template includes all the elements necessary to create a successful business plan, from data collection to analysis of the best method to comprehend concepts, opinions, or experiences. Get it now.

Template 12 : Qualitative Research Analysis of Comments with Magnify Glass

The first step in performing a qualitative analysis of your data is gathering all the comments and feedback you want to look at. Our templates help you document those comments. These slides are fully editable and contain a visual accessibility function. The organization and formatting of the sections are excellent. Download it now.

PS For more information on qualitative and quantitative data analysis, as well as to determine which type of market research is best for your company, check out this blog.

FAQs on Qualitative Research

Writing a qualitative research report.

A qualitative report is a summary of an experience, activity, event, or observation. The format of a qualitative report includes an abstract, introduction, background information on the issue, the researcher's role, theoretical viewpoint, methodology, ethical considerations, results, data analysis, limitations, discussion, conclusions, implications, references, and an appendix. A qualitative research report requires extensive detail and is typically divided into several sections. These start with the title, a table of contents, and an abstract; these form the beginning. Then, the meat of a qualitative report comprises an introduction, the literature review, an account of investigation, findings, discussion, and conclusions. The final section is references.

How do you Report Data in Qualitative Research?

A qualitative research report is frequently built around themes. You should be aware that it can be difficult to express qualitative findings as thoroughly as they deserve. It is customary to use direct quotes from sources like interviews to support the viewpoint. To develop a precise description or explanation of the primary theme being studied, it is also crucial to clarify concepts and connect them. There is the need to state about design, which is how were the subject choices made, leading through other steps to documenting that how the researcher verified the research’s findings/results.

What is an Example of a Report of Qualitative Data?

Qualitative data are categorical by nature. Reports that use qualitative data make it easier to present complex information. The semi-structured interview is one of the best illustrations of a qualitative data collection technique that provides open-ended responses from informants while allowing researchers to ask questions based on a set of predetermined themes. Since they enable both inductive and deductive evaluative reasoning, these are crucial tools for qualitative research.

How do you write an Introduction for a Qualitative Report?

A qualitative report must have a strong introduction. In this section, the researcher emphasizes the aims and objectives of the methodical study. It also addresses the problem that the systematic study aims to solve. In this section, it's imperative to state whether the research's goals were met. The researcher goes into further depth about the research problem in the introduction part and discusses the need for a methodical enquiry. The researcher must define any technical words or phrases used.

Related posts:

- [Updated 2023] Report Writing Format with Sample Report Templates

- Top 10 Academic Report and Document Templates

- 10 Best PowerPoint Templates for Non-Profit Organizations

- Top 10 Proposal Executive Summary Templates With Samples And Examples

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 Business Investment Proposal Templates With Samples and Examples (Free PDF Attached)

Top 10 Marketing Cover Letter Templates With Samples and Examples (Free PDF Attached)

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

--> Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

--> Sales funnel results presentation layouts

--> 3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

--> Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Future plan powerpoint template slide

--> Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

--> Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

--> Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

--> Agenda powerpoint slide show

--> Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

--> Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

--> Meet our team representing in circular format

Sample articles

Qualitative psychology ®.

- Recommendations for Designing and Reviewing Qualitative Research in Psychology: Promoting Methodological Integrity (PDF, 166KB) February 2017 by Heidi M. Levitt, Sue L. Motulsky, Fredrick J. Wertz, Susan L. Morrow, and Joseph G. Ponterotto

- Racial Microaggression Experiences and Coping Strategies of Black Women in Corporate Leadership (PDF, 132KB) August 2015 by Aisha M. B. Holder, Margo A. Jackson, and Joseph G. Ponterotto

- The Lived Experience of Homeless Youth: A Narrative Approach (PDF, 109KB) February 2015 by Erin E. Toolis and Phillip L. Hammack

- Lifetime Activism, Marginality, and Psychology: Narratives of Lifelong Feminist Activists Committed to Social Change (PDF, 93KB) August 2014 by Anjali Dutt and Shelly Grabe

- Qualitative Inquiry in the History of Psychology (PDF, 82KB) February 2014 by Frederick J. Wertz

More About this Journal

- Qualitative Psychology

- Pricing and subscription info

- Special section proposal guidelines

- Special sections

- Call for articles: Methodological Retrospectives

Contact Journals

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

A synthesis of recommendations.

O’Brien, Bridget C. PhD; Harris, Ilene B. PhD; Beckman, Thomas J. MD; Reed, Darcy A. MD, MPH; Cook, David A. MD, MHPE

Dr. O’Brien is assistant professor, Department of Medicine and Office of Research and Development in Medical Education, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, San Francisco, California.

Dr. Harris is professor and head, Department of Medical Education, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Dr. Beckman is professor of medicine and medical education, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Dr. Reed is associate professor of medicine and medical education, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Dr. Cook is associate director, Mayo Clinic Online Learning, research chair, Mayo Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, and professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Funding/Support: This study was funded in part by a research review grant from the Society for Directors of Research in Medical Education.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Disclaimer: The funding agency had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 .

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. O’Brien, Office of Research and Development in Medical Education, UCSF School of Medicine, Box 3202, 1855 Folsom St., Suite 200, San Francisco, CA 94143-3202; e-mail: [email protected] .

Purpose

Standards for reporting exist for many types of quantitative research, but currently none exist for the broad spectrum of qualitative research. The purpose of the present study was to formulate and define standards for reporting qualitative research while preserving the requisite flexibility to accommodate various paradigms, approaches, and methods.

Method

The authors identified guidelines, reporting standards, and critical appraisal criteria for qualitative research by searching PubMed, Web of Science, and Google through July 2013; reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources; and contacting experts. Specifically, two authors reviewed a sample of sources to generate an initial set of items that were potentially important in reporting qualitative research. Through an iterative process of reviewing sources, modifying the set of items, and coding all sources for items, the authors prepared a near-final list of items and descriptions and sent this list to five external reviewers for feedback. The final items and descriptions included in the reporting standards reflect this feedback.

Results

The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) consists of 21 items. The authors define and explain key elements of each item and provide examples from recently published articles to illustrate ways in which the standards can be met.

Conclusions

The SRQR aims to improve the transparency of all aspects of qualitative research by providing clear standards for reporting qualitative research. These standards will assist authors during manuscript preparation, editors and reviewers in evaluating a manuscript for potential publication, and readers when critically appraising, applying, and synthesizing study findings.

Qualitative research contributes to the literature in many disciplines by describing, interpreting, and generating theories about social interactions and individual experiences as they occur in natural, rather than experimental, situations. 1–3 Some recent examples include studies of professional dilemmas, 4 medical students’ early experiences of workplace learning, 5 patients’ experiences of disease and interventions, 6–8 and patients’ perspectives about incident disclosures. 9 The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the perspectives/experiences of individuals or groups and the contexts in which these perspectives or experiences are situated. 1 , 2 , 10

Qualitative research is increasingly common and valued in the medical and medical education literature. 1 , 10–13 However, the quality of such research can be difficult to evaluate because of incomplete reporting of key elements. 14 , 15 Quality is multifaceted and includes consideration of the importance of the research question, the rigor of the research methods, the appropriateness and salience of the inferences, and the clarity and completeness of reporting. 16 , 17 Although there is much debate about standards for methodological rigor in qualitative research, 13 , 14 , 18–20 there is widespread agreement about the need for clear and complete reporting. 14 , 21 , 22 Optimal reporting would enable editors, reviewers, other researchers, and practitioners to critically appraise qualitative studies and apply and synthesize the results. One important step in improving the quality of reporting is to formulate and define clear reporting standards.

Authors have proposed guidelines for the quality of qualitative research, including those in the fields of medical education, 23–25 clinical and health services research, 26–28 and general education research. 29 , 30 Yet in nearly all cases, the authors do not describe how the guidelines were created, and often fail to distinguish reporting quality from the other facets of quality (e.g., the research question or methods). Several authors suggest standards for reporting qualitative research, 15 , 20 , 29–33 but their articles focus on a subset of qualitative data collection methods (e.g., interviews), fail to explain how the authors developed the reporting criteria, narrowly construe qualitative research (e.g., thematic analysis) in ways that may exclude other approaches, and/or lack specific examples to help others see how the standards might be achieved. Thus, there remains a compelling need for defensible and broadly applicable standards for reporting qualitative research.

We designed and carried out the present study to formulate and define standards for reporting qualitative research through a rigorous synthesis of published articles and expert recommendations.

We formulated standards for reporting qualitative research by using a rigorous and systematic approach in which we reviewed previously proposed recommendations by experts in qualitative methods. Our research team consisted of two PhD researchers and one physician with formal training and experience in qualitative methods, and two physicians with experience, but no formal training, in qualitative methods.

We first identified previously proposed recommendations by searching PubMed, Web of Science, and Google using combinations of terms such as “qualitative methods,” “qualitative research,” “qualitative guidelines,” “qualitative standards,” and “critical appraisal” and by reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources, reviewing the Equator Network, 22 and contacting experts. We conducted our first search in January 2007 and our last search in July 2013. Most recommendations were published in peer-reviewed journals, but some were available only on the Internet, and one was an interim draft from a national organization. We report the full set of the 40 sources reviewed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 .

Two of us (B.O., I.H.) reviewed an initial sample of sources to generate a comprehensive list of items that were potentially important in reporting qualitative research (Draft A). All of us then worked in pairs to review all sources and code the presence or absence of each item in a given source. From Draft A, we then distilled a shorter list (Draft B) by identifying core concepts and combining related items, taking into account the number of times each item appeared in these sources. We then compared the items in Draft B with material in the original sources to check for missing concepts, modify accordingly, and add explanatory definitions to create a prefinal list of items (Draft C).

We circulated Draft C to five experienced qualitative researchers (see the acknowledgments) for review. We asked them to note any omitted or redundant items and to suggest improvements to the wording to enhance clarity and relevance across a broad spectrum of qualitative inquiry. In response to their reviews, we consolidated some items and made minor revisions to the wording of labels and definitions to create the final set of reporting standards—the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)—summarized in Table 1 .

To explicate how the final set of standards reflect the material in the original sources, two of us (B.O., D.A.C.) selected by consensus the 25 most complete sources of recommendations and identified which standards reflected the concepts found in each original source (see Table 2 ).

The SRQR is a list of 21 items that we consider essential for complete, transparent reporting of qualitative research (see Table 1 ). As explained above, we developed these items through a rigorous synthesis of prior recommendations and concepts from published sources (see Table 2 ; see also Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 ) and expert review. These 21 items provide a framework and recommendations for reporting qualitative studies. Given the wide range of qualitative approaches and methodologies, we attempted to select items with broad relevance.

The SRQR includes the article’s title and abstract (items 1 and 2); problem formulation and research question (items 3 and 4); research design and methods of data collection and analysis (items 5 through 15); results, interpretation, discussion, and integration (items 16 through 19); and other information (items 20 and 21). Supplemental Digital Appendix 2, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 , contains a detailed explanation of each item, along with examples from recently published qualitative studies. Below, we briefly describe the standards, with a particular focus on those unique to qualitative research.

Titles, abstracts, and introductory material. Reporting standards for titles, abstracts, and introductory material (problem formulation, research question) in qualitative research are very similar to those for quantitative research, except that the results reported in the abstract are narrative rather than numerical, and authors rarely present a specific hypothesis. 29 , 30

Research design and methods. Reporting on research design and methods of data collection and analysis highlights several distinctive features of qualitative research. Many of the criteria we reviewed focus not only on identifying and describing all aspects of the methods (e.g., approach, researcher characteristics and role, sampling strategy, context, data collection and analysis) but also on justifying each choice. 13 , 14 This ensures that authors make their assumptions and decisions transparent to readers. This standard is less commonly expected in quantitative research, perhaps because most quantitative researchers share positivist assumptions and generally agree about standards for rigor of various study designs and sampling techniques. 14 Just as quantitative reporting standards encourage authors to describe how they implemented methods such as randomization and measurement validity, several qualitative reporting criteria recommend that authors describe how they implemented a presumably familiar technique in their study rather than simply mentioning the technique. 10 , 14 , 32 For example, authors often state that data collection occurred until saturation, with no mention of how they defined and recognized saturation. Similarly, authors often mention an “iterative process,” with minimal description of the nature of the iterations. The SRQR emphasizes the importance of explaining and elaborating on these important processes. Nearly all of the original sources recommended describing the characteristics and role of the researcher (i.e., reflexivity). Members of the research team often form relationships with participants, and analytic processes are highly interpretive in most qualitative research. Therefore, reviewers and readers must understand how these relationships and the researchers’ perspectives and assumptions influenced data collection and interpretation. 15 , 23 , 26 , 34

Results. Reporting of qualitative research results should identify the main analytic findings. Often, these findings involve interpretation and contextualization, which represent a departure from the tradition in quantitative studies of objectively reporting results. The presentation of results often varies with the specific qualitative approach and methodology; thus, rigid rules for reporting qualitative findings are inappropriate. However, authors should provide evidence (e.g., examples, quotes, or text excerpts) to substantiate the main analytic findings. 20 , 29

Discussion. The discussion of qualitative results will generally include connections to existing literature and/or theoretical or conceptual frameworks, the scope and boundaries of the results (transferability), and study limitations. 10–12 , 28 In some qualitative traditions, the results and discussion may not have distinct boundaries; we recommend that authors include the substance of each item regardless of the section in which it appears.

The purpose of the SRQR is to improve the quality of reporting of qualitative research studies. We hope that these 21 recommended reporting standards will assist authors during manuscript preparation, editors and reviewers in evaluating a manuscript for potential publication, and readers when critically appraising, applying, and synthesizing study findings. As with other reporting guidelines, 35–37 we anticipate that the SRQR will evolve as it is applied and evaluated in practice. We welcome suggestions for refinement.

Qualitative studies explore “how?” and “why?” questions related to social or human problems or phenomena. 10 , 38 Purposes of qualitative studies include understanding meaning from participants’ perspectives (How do they interpret or make sense of an event, situation, or action?); understanding the nature and influence of the context surrounding events or actions; generating theories about new or poorly understood events, situations, or actions; and understanding the processes that led to a desired (or undesired) outcome. 38 Many different approaches (e.g., ethnography, phenomenology, discourse analysis, case study, grounded theory) and methodologies (e.g., interviews, focus groups, observation, analysis of documents) may be used in qualitative research, each with its own assumptions and traditions. 1 , 2 A strength of many qualitative approaches and methodologies is the opportunity for flexibility and adaptability throughout the data collection and analysis process. We endeavored to maintain that flexibility by intentionally defining items to avoid favoring one approach or method over others. As such, we trust that the SRQR will support all approaches and methods of qualitative research by making reports more explicit and transparent, while still allowing investigators the flexibility to use the study design and reporting format most appropriate to their study. It may be helpful, in the future, to develop approach-specific extensions of the SRQR, as has been done for guidelines in quantitative research (e.g., the CONSORT extensions). 37

Limitations, strengths, and boundaries

We deliberately avoided recommendations that define methodological rigor, and therefore it would be inappropriate to use the SRQR to judge the quality of research methods and findings. Many of the original sources from which we derived the SRQR were intended as criteria for methodological rigor or critical appraisal rather than reporting; for these, we inferred the information that would be needed to evaluate the criterion. Occasionally, we found conflicting recommendations in the literature (e.g., recommending specific techniques such as multiple coders or member checking to demonstrate trustworthiness); we resolved these conflicting recommendations through selection of the most frequent recommendations and by consensus among ourselves.

Some qualitative researchers have described the limitations of checklists as a means to improve methodological rigor. 13 We nonetheless believe that a checklist for reporting standards will help to enhance the transparency of qualitative research studies and thereby advance the field. 29 , 39

Strengths of this work include the grounding in previously published criteria, the diversity of experience and perspectives among us, and critical review by experts in three countries.

Implications and application

Similar to other reporting guidelines, 35–37 the SRQR may be viewed as a starting point for defining reporting standards in qualitative research. Although our personal experience lies in health professions education, the SRQR is based on sources originating in diverse health care and non-health-care fields. We intentionally crafted the SRQR to include various paradigms, approaches, and methodologies used in qualitative research. The elaborations offered in Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 (see https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 ) should provide sufficient description and examples to enable both novice and experienced researchers to use these standards. Thus, the SRQR should apply broadly across disciplines, methodologies, topics, study participants, and users.

The SRQR items reflect information essential for inclusion in a qualitative research report, but should not be viewed as prescribing a rigid format or standardized content. Individual study needs, author preferences, and journal requirements may necessitate a different sequence or organization than that shown in Table 1 . Journal word restrictions may prevent a full exposition of each item, and the relative importance of a given item will vary by study. Thus, although all 21 standards would ideally be reflected in any given report, authors should prioritize attention to those items that are most relevant to the given study, findings, context, and readership.

Application of the SRQR need not be limited to the writing phase of a given study. These standards can assist researchers in planning qualitative studies and in the careful documentation of processes and decisions made throughout the study. By considering these recommendations early on, researchers may be more likely to identify the paradigm and approach most appropriate to their research, consider and use strategies for ensuring trustworthiness, and keep track of procedures and decisions.

Journal editors can facilitate the review process by providing the SRQR to reviewers and applying its standards, thus establishing more explicit expectations for qualitative studies. Although the recommendations do not address or advocate specific approaches, methods, or quality standards, they do help reviewers identify information that is missing from manuscripts.

As authors and editors apply the SRQR, readers will have more complete information about a given study, thus facilitating judgments about the trustworthiness, relevance, and transferability of findings to their own context and/or to related literature. Complete reporting will also facilitate meaningful synthesis of qualitative results across studies. 40 We anticipate that such transparency will, over time, help to identify previously unappreciated gaps in the rigor and relevance of research findings. Investigators, editors, and educators can then work to remedy these deficiencies and, thereby, enhance the overall quality of qualitative research.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Margaret Bearman, PhD, Calvin Chou, MD, PhD, Karen Hauer, MD, Ayelet Kuper, MD, DPhil, Arianne Teherani, PhD, and participants in the UCSF weekly educational scholarship works-in-progress group (ESCape) for critically reviewing the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

References Cited Only in Table 2

Supplemental digital content.

- ACADMED_89_9_2014_05_22_OBRIEN_1301196_SDC1.pdf; [PDF] (385 KB)

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework, common qualitative methodologies and research designs in health professions..., the positivism paradigm of research, summary of instructions for authors, the problem and power of professionalism: a critical analysis of medical....

Qualitative research: methods and examples

Last updated

13 April 2023

Reviewed by

Qualitative research involves gathering and evaluating non-numerical information to comprehend concepts, perspectives, and experiences. It’s also helpful for obtaining in-depth insights into a certain subject or generating new research ideas.

As a result, qualitative research is practical if you want to try anything new or produce new ideas.

There are various ways you can conduct qualitative research. In this article, you'll learn more about qualitative research methodologies, including when you should use them.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a broad term describing various research types that rely on asking open-ended questions. Qualitative research investigates “how” or “why” certain phenomena occur. It is about discovering the inherent nature of something.

The primary objective of qualitative research is to understand an individual's ideas, points of view, and feelings. In this way, collecting in-depth knowledge of a specific topic is possible. Knowing your audience's feelings about a particular subject is important for making reasonable research conclusions.

Unlike quantitative research , this approach does not involve collecting numerical, objective data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is used extensively in education, sociology, health science, history, and anthropology.

- Types of qualitative research methodology

Typically, qualitative research aims at uncovering the attitudes and behavior of the target audience concerning a specific topic. For example, “How would you describe your experience as a new Dovetail user?”

Some of the methods for conducting qualitative analysis include:

Focus groups

Hosting a focus group is a popular qualitative research method. It involves obtaining qualitative data from a limited sample of participants. In a moderated version of a focus group, the moderator asks participants a series of predefined questions. They aim to interact and build a group discussion that reveals their preferences, candid thoughts, and experiences.

Unmoderated, online focus groups are increasingly popular because they eliminate the need to interact with people face to face.

Focus groups can be more cost-effective than 1:1 interviews or studying a group in a natural setting and reporting one’s observations.

Focus groups make it possible to gather multiple points of view quickly and efficiently, making them an excellent choice for testing new concepts or conducting market research on a new product.

However, there are some potential drawbacks to this method. It may be unsuitable for sensitive or controversial topics. Participants might be reluctant to disclose their true feelings or respond falsely to conform to what they believe is the socially acceptable answer (known as response bias).

Case study research

A case study is an in-depth evaluation of a specific person, incident, organization, or society. This type of qualitative research has evolved into a broadly applied research method in education, law, business, and the social sciences.

Even though case study research may appear challenging to implement, it is one of the most direct research methods. It requires detailed analysis, broad-ranging data collection methodologies, and a degree of existing knowledge about the subject area under investigation.

Historical model

The historical approach is a distinct research method that deeply examines previous events to better understand the present and forecast future occurrences of the same phenomena. Its primary goal is to evaluate the impacts of history on the present and hence discover comparable patterns in the present to predict future outcomes.

Oral history

This qualitative data collection method involves gathering verbal testimonials from individuals about their personal experiences. It is widely used in historical disciplines to offer counterpoints to established historical facts and narratives. The most common methods of gathering oral history are audio recordings, analysis of auto-biographical text, videos, and interviews.

Qualitative observation

One of the most fundamental, oldest research methods, qualitative observation , is the process through which a researcher collects data using their senses of sight, smell, hearing, etc. It is used to observe the properties of the subject being studied. For example, “What does it look like?” As research methods go, it is subjective and depends on researchers’ first-hand experiences to obtain information, so it is prone to bias. However, it is an excellent way to start a broad line of inquiry like, “What is going on here?”

Record keeping and review

Record keeping uses existing documents and relevant data sources that can be employed for future studies. It is equivalent to visiting the library and going through publications or any other reference material to gather important facts that will likely be used in the research.

Grounded theory approach

The grounded theory approach is a commonly used research method employed across a variety of different studies. It offers a unique way to gather, interpret, and analyze. With this approach, data is gathered and analyzed simultaneously. Existing analysis frames and codes are disregarded, and data is analyzed inductively, with new codes and frames generated from the research.

Ethnographic research

Ethnography is a descriptive form of a qualitative study of people and their cultures. Its primary goal is to study people's behavior in their natural environment. This method necessitates that the researcher adapts to their target audience's setting.

Thereby, you will be able to understand their motivation, lifestyle, ambitions, traditions, and culture in situ. But, the researcher must be prepared to deal with geographical constraints while collecting data i.e., audiences can’t be studied in a laboratory or research facility.

This study can last from a couple of days to several years. Thus, it is time-consuming and complicated, requiring you to have both the time to gather the relevant data as well as the expertise in analyzing, observing, and interpreting data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Narrative framework

A narrative framework is a qualitative research approach that relies on people's written text or visual images. It entails people analyzing these events or narratives to determine certain topics or issues. With this approach, you can understand how people represent themselves and their experiences to a larger audience.

Phenomenological approach

The phenomenological study seeks to investigate the experiences of a particular phenomenon within a group of individuals or communities. It analyzes a certain event through interviews with persons who have witnessed it to determine the connections between their views. Even though this method relies heavily on interviews, other data sources (recorded notes), and observations could be employed to enhance the findings.

- Qualitative research methods (tools)

Some of the instruments involved in qualitative research include:

Document research: Also known as document analysis because it involves evaluating written documents. These can include personal and non-personal materials like archives, policy publications, yearly reports, diaries, or letters.

Focus groups: This is where a researcher poses questions and generates conversation among a group of people. The major goal of focus groups is to examine participants' experiences and knowledge, including research into how and why individuals act in various ways.

Secondary study: Involves acquiring existing information from texts, images, audio, or video recordings.

Observations: This requires thorough field notes on everything you see, hear, or experience. Compared to reported conduct or opinion, this study method can assist you in getting insights into a specific situation and observable behaviors.

Structured interviews : In this approach, you will directly engage people one-on-one. Interviews are ideal for learning about a person's subjective beliefs, motivations, and encounters.

Surveys: This is when you distribute questionnaires containing open-ended questions

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- What are common examples of qualitative research?

Everyday examples of qualitative research include:

Conducting a demographic analysis of a business

For instance, suppose you own a business such as a grocery store (or any store) and believe it caters to a broad customer base, but after conducting a demographic analysis, you discover that most of your customers are men.

You could do 1:1 interviews with female customers to learn why they don't shop at your store.

In this case, interviewing potential female customers should clarify why they don't find your shop appealing. It could be because of the products you sell or a need for greater brand awareness, among other possible reasons.

Launching or testing a new product

Suppose you are the product manager at a SaaS company looking to introduce a new product. Focus groups can be an excellent way to determine whether your product is marketable.

In this instance, you could hold a focus group with a sample group drawn from your intended audience. The group will explore the product based on its new features while you ensure adequate data on how users react to the new features. The data you collect will be key to making sales and marketing decisions.

Conducting studies to explain buyers' behaviors

You can also use qualitative research to understand existing buyer behavior better. Marketers analyze historical information linked to their businesses and industries to see when purchasers buy more.

Qualitative research can help you determine when to target new clients and peak seasons to boost sales by investigating the reason behind these behaviors.

- Qualitative research: data collection

Data collection is gathering information on predetermined variables to gain appropriate answers, test hypotheses, and analyze results. Researchers will collect non-numerical data for qualitative data collection to obtain detailed explanations and draw conclusions.

To get valid findings and achieve a conclusion in qualitative research, researchers must collect comprehensive and multifaceted data.

Qualitative data is usually gathered through interviews or focus groups with videotapes or handwritten notes. If there are recordings, they are transcribed before the data analysis process. Researchers keep separate folders for the recordings acquired from each focus group when collecting qualitative research data to categorize the data.

- Qualitative research: data analysis

Qualitative data analysis is organizing, examining, and interpreting qualitative data. Its main objective is identifying trends and patterns, responding to research questions, and recommending actions based on the findings. Textual analysis is a popular method for analyzing qualitative data.

Textual analysis differs from other qualitative research approaches in that researchers consider the social circumstances of study participants to decode their words, behaviors, and broader meaning.

Learn more about qualitative research data analysis software

- When to use qualitative research

Qualitative research is helpful in various situations, particularly when a researcher wants to capture accurate, in-depth insights.

Here are some instances when qualitative research can be valuable:

Examining your product or service to improve your marketing approach

When researching market segments, demographics, and customer service teams

Identifying client language when you want to design a quantitative survey

When attempting to comprehend your or someone else's strengths and weaknesses

Assessing feelings and beliefs about societal and public policy matters

Collecting information about a business or product's perception

Analyzing your target audience's reactions to marketing efforts

When launching a new product or coming up with a new idea

When seeking to evaluate buyers' purchasing patterns

- Qualitative research methods vs. quantitative research methods

Qualitative research examines people's ideas and what influences their perception, whereas quantitative research draws conclusions based on numbers and measurements.

Qualitative research is descriptive, and its primary goal is to comprehensively understand people's attitudes, behaviors, and ideas.

In contrast, quantitative research is more restrictive because it relies on numerical data and analyzes statistical data to make decisions. This research method assists researchers in gaining an initial grasp of the subject, which deals with numbers. For instance, the number of customers likely to purchase your products or use your services.

What is the most important feature of qualitative research?

A distinguishing feature of qualitative research is that it’s conducted in a real-world setting instead of a simulated environment. The researcher is examining actual phenomena instead of experimenting with different variables to see what outcomes (data) might result.

Can I use qualitative and quantitative approaches together in a study?

Yes, combining qualitative and quantitative research approaches happens all the time and is known as mixed methods research. For example, you could study individuals’ perceived risk in a certain scenario, such as how people rate the safety or riskiness of a given neighborhood. Simultaneously, you could analyze historical data objectively, indicating how safe or dangerous that area has been in the last year. To get the most out of mixed-method research, it’s important to understand the pros and cons of each methodology, so you can create a thoughtfully designed study that will yield compelling results.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Qualitative research examples

UserTesting

Qualitative research is a powerful tool that helps you unlock insights into the user experience—quintessential to building effective products and services. It provides a deeper understanding of complex behaviors, needs, and motivations. But what is qualitative research, and when is it ideal to use it? Let’s explore its methodologies and implementation with a few qualitative research examples.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a behavioral research method that seeks to understand the undertones, motivations, and subjective interpretations inherent in human behavior. It involves gathering nonnumerical data, such as text, audio, and video, allowing you to explore nuances and patterns that quantitative data can’t capture.

Instead of focusing on how many or how much, qualitative research questions delve into the why and how. This approach is instrumental in gaining a comprehensive understanding of a particular context, issue, or phenomenon from the perspective of those experiencing it. Examples of qualitative research questions include “How did you feel when you first used our product?” and “Could you describe your experience when you purchased a product from our website?”

Qualitative research methodology

Qualitative research design employs a variety of methodologies to collect and analyze data. The primary objective is to gather detailed and nuanced insights rather than generalizable findings. Steps include the following:

- Formulating research questions: Qualitative research begins by identifying specific research questions to guide the study. These questions should align with the research objectives and provide a clear focus for data collection and analysis.

- Selection of participants: Participant selection is a critical step in qualitative research. You must recruit participants who provide relevant and diverse perspectives on the research topic. It involves purposive sampling, where participants are chosen based on their knowledge or experiences related to the research questions.

- Data collection: Qualitative research uses various methods to collect data, such as interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You often employ multiple methods to comprehensively understand the research topic.

- Data analysis: Once the data is collected, it’s analyzed to identify recurring themes, patterns, and meanings. This analysis uses coding, thematic analysis, and constant comparison. The goal is to uncover the underlying perspectives of the participant.

- Interpretation and reporting: This is the final step in which findings are synthesized and interpreted, revealing their significance to the research questions. You can present your findings through descriptive narratives, quotes, and illustrative examples to provide a rich understanding of the research topic.

Types of qualitative research methods

The best qualitative research method primarily depends on your research questions and objectives. Different methods uncover different discernments.

One-on-one interviews

You often use one-on-one interviews to delve deep into a topic or understand individual experiences or perspectives. An interviewer asks a participant open-ended questions to understand their perspective, thoughts, feelings, and experiences regarding a specific topic, product, or service. Read about open ended vs closed ended questions to learn which questions will be most effective in an interview.

Say you’re developing a new electric vehicle mode. You can conduct one-on-one interviews to understand user experiences, probing into aspects such as comfort, design, driving experience, and more.

Focus groups

In-person or remote focus groups involve a small group of people (usually 6–10) discussing a given topic or question under the guidance of a moderator. This method is beneficial when you want to understand group dynamics or collective views. The interaction among group members can disclose awarenesses that may not arise in one-on-one interviews.

In the gaming industry, for example, you can use focus groups to explore player reactions to a new game design. You can encourage group interaction to spark discussions about usability, game mechanics, graphics, storyline, and other aspects.

Case study research

Case study research provides an in-depth analysis of a particular case (an individual, group, organization, event, etc.) within its real-life context. It’s a valuable method for exploring something in-depth and in its natural setting.

For instance, a healthcare case study could explore implementing a new electronic health record system in a hospital, focusing on challenges, successes, and lessons learned.

Ethnographic research

Ethnographic research (or an ethnographic stud y) involves an immersive investigation into a group’s behaviors, culture, and practices. It requires you to engage directly with the participants over a prolonged period in their natural environment. It can help uncover how people interact with products or services in natural settings.

A gaming organization may choose to study players in their natural gaming environments (such as home, game cafes, or e-sport tournaments) to understand their gaming habits, social interactions, and responses to specific features. These insights can inform the development of more engaging and user-friendly games.

Process of observation

The process of observation typically doesn’t involve the same level of immersion as ethnographic research. You observe and record behavior related to a specific context or activity. It can be in natural settings (naturalistic observation) or a controlled environment. It’s more about observing and recording specific behaviors or situations rather than cultural norms or dynamics.

For example, a consumer technology organization could observe how users interact with a new software interface, noting challenges, efficiencies, and overall user experience.

Record keeping

Record keeping refers to collecting and analyzing documents, records, and artifacts that provide an understanding of the study area. Record keeping allows you to access historical and contextual data that can be examined and reexamined. It’s a nonobtrusive method, meaning it doesn’t involve direct contact with the participants, nor does it affect or alter the situation you’re studying.

An online retailer might examine shopping cart abandonment records to identify at what point in the buying process customers tend to drop off. This information can help streamline the checkout process and improve conversion rates.

Qualitative research: Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis in qualitative research are closely linked processes that help generate meaningful and useful results.

Data collection

Data collection involves gathering rich, detailed materials to explain and understand the subject. These include interview transcripts, meeting notes, personal diaries, and photographs.

There are various qualitative data collection methods to consider depending on your research questions and the context of your study. For example, you could use one-on-one interviews to understand personal user experiences with a financial services app. A moderated focus group may be more appropriate to discuss user preferences in a new media and entertainment platform.

Data analysis

Once data are collected, the analysis process begins. It’s where you extract patterns, themes, and insights from the collected data. It’s one of the most critical aspects of qualitative research, turning raw, unstructured data into valuable insights.

Qualitative data analysis usually takes place with several steps, such as:

- Organizing and preparing the data for analysis

- Reading through the data

- Coding the data

- Generating themes or categories

- Interpreting the findings and

- Representing the data

Your choice of qualitative data analysis method depends on your research questions and the data type you collected. Common analysis methods include thematic, content, discourse, and narrative analysis. Some research platforms provide AI features that can do much of this analysis for researchers to speed up insight gathering.

When to use qualitative research

Qualitative techniques are ideal for understanding human experiences and perspectives. Here are common situations where qualitative research is invaluable:

- Exploring customer motivations, needs, behaviors, and pain points

- Gathering in-depth user feedback on products and services

- Understanding decision-making and buyer journeys

- Discovering barriers to adoption and satisfaction

- Developing hypotheses for future quantitative research

- Testing concepts , interfaces, or designs

- Identifying problems and improvement opportunities

- Learning about group norms, cultures, and social interactions

- Collecting evidence to develop theories and models

- Capturing complex, nuanced insights beyond numbers

Qualitative research methods vs. quantitative research methods

Qualitative and quantitative research differ in their approach to data collection, analysis, and the nature of the findings. Here are some key differences:

- Data collection: Qualitative research uses in-depth interviews , focus groups, observations, and analysis of documents to gather data. In contrast, quantitative research relies on structured surveys, experiments, and standard measurements.

- Analysis: Qualitative research involves analyzing textual or visual data through coding, categorization, and theme identification techniques. Quantitative research uses statistical analysis to examine numerical data for patterns, correlations, and trends.

- Sample size: Qualitative research typically involves smaller sample sizes, often selected through purposive sampling to ensure diversity and relevance. Quantitative research uses larger sample sizes to ensure statistical power and generalizability.

- Generalizability: Qualitative research seeks in-depth insight into specific contexts or groups and does not prioritize generalizability. On the other hand, quantitative research seeks to draw conclusions that apply to a broader context.

- Findings: Qualitative research generates descriptive and explanatory results that provide a deeper understanding of phenomena. Quantitative research produces numerical data that allows for statistical inferences and comparisons.

- Theory development: Qualitative research often contributes to theory development by generating new concepts, theories, or frameworks based on the rich and context-specific data collected. However, quantitative research tests preexisting theories and hypotheses using statistical models.

Advantages and strengths of qualitative research

Qualitative research enriches your research process and outcomes, making it an invaluable tool in many fields, including UX research, marketing, and digital product development.

In-depth understanding

Qualitative research provides a rich, detailed, in-depth understanding of the research subject. Proactive qualitative research takes this further with ongoing data collection, allowing organizations to continuously capture insights and adapt strategies based on evolving user needs.

Contextual data

Qualitative research collects contextually relevant data. It captures nuances that might be missed in numerically-based quantitative data, allowing you to understand the contexts in which behaviors and interactions occur.

Flexibility

The methods used in qualitative research, like interviews and focus groups, enable you to explore different topics in depth and adapt your approach based on the participants’ responses.

Human perspective

Qualitative research lets you capture human experiences and thoughts. It’s advantageous in fields such as UX research, where the human perspective is critical.

Hypothesis generation

The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps you identify new areas for exploration or generate hypotheses you can test using quantitative methods.

Trendspotting

Qualitative research reveals trends in thought and opinions, diving deeper into the problem. This is helpful when trying to understand behaviors, culture, and user interactions.

Disadvantages and limitations of qualitative research

While qualitative research offers many advantages, it’s essential to acknowledge its limitations.

Time-consuming

Collecting and analyzing qualitative data, particularly from in-depth interviews or focus groups, requires significant time investment.

Qualitative research relies on the skills and judgment of the researcher, introducing potential bias into the research process. The researcher may actively shape the research by posing questions, interpreting data, and influencing the findings.

Requires skilled researchers

The quality of qualitative research heavily depends on the researcher’s skills, experience, and perspective. A less experienced researcher may overlook important nuances, potentially affecting the depth and accuracy of the findings.

Lacks generalizability

Qualitative research often involves a smaller, nonrepresentative sample size than quantitative research. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to a larger context.

Limited numeric representation

Qualitative research usually focuses on words, observations, or experiences, so it doesn’t provide the numeric estimates often desired in research studies.

Challenging to replicate and standardize

Qualitative research’s inherent flexibility and context dependence make it challenging to repeat the study under the same conditions. This flexibility can often make it hard to standardize. Researchers approach and conduct the study in various ways, leading to inconsistent results and interpretations.

Difficult to measure reliability and validity

Assessing reliability and validity is more difficult with qualitative research since it relies on subjective human interpretation and has few established metrics and statistical tools compared to quantitative research. Triangulation and member checking add credibility but lack the discreteness of quantitative measures. However, there have been advancement s in the measurement of qualitative research that help to quantify its impact.

Qualitative research gives you the opportunity to dive deep into human behavior, experiences, and perceptions. It offers a prolific, intricate perspective that quantifiable data alone can’t provide. Combine qualitative research methodologies with techniques like A/B testing to gain a more holistic understanding of user experiences and preferences.

Despite its limitations, the depth and richness of data procured through qualitative research are undeniable assets. By understanding and utilizing its diverse methods, you will uncover detailed insights from your target audience and enhance your products or services to meet their needs.

The UX research methodology guidebook

Learn how to gather the user feedback you need to build best-in-class products.

In this Article

Get started now

Why is qualitative research important?

Qualitative research delves into subjective experiences and social contexts, providing in-depth insights and understanding. It provides a deep understanding of individuals’ needs, motivations, and preferences, allowing organizations to develop products and services that meet customer expectations.

What’s the difference between quantitative and qualitative methods?