What are the key components of the anthropological perspective?

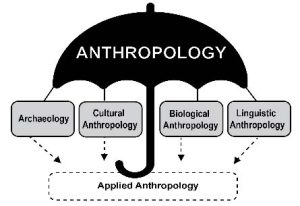

Anthropology is the study of human commonalities and diversity. It seeks answers to questions about the different ways of being human, the commonalities and differences between societies in different parts of the world, the impact of different lifestyles and how these developed over time. The anthropological perspective includes several key components. These include a holistic approach to understanding human behaviour, an emphasis on cultural relativism, and a commitment to participant observation as a method of data collection.

Additionally, anthropologists often focus on the ways in which power structures and social inequalities shape human experience, and they may also examine the intersections between biology and culture.

Overall, the anthropological perspective seeks to understand the diversity of human experiences across time and space while also recognizing the interconnectedness of all aspects of human life.

There are three key components of the anthropological perspective – they are comparative or cross-cultural studies, holism and cultural relativism.

Components of the Anthropological Perspective (1) – Comparative or cross-cultural studies

It is not possible to understand human diversity without studying diverse cultures.

An anthropologist approaches the study of different societies with fresh eyes and an open mind. They seek to understand what holds a society together, what makes it function the way it does, and how it has adapted to its environment –

- What holds a society together.

- What makes it function the way it does.

- How the society has adapted to the environment.

- The main modes of communication within the society.

- How the people’s past has shaped their culture.

Only then will an anthropologist be able to trace the impact of different forces on the formation of human culture.

It is also interesting to note that when one views a situation as an “outsider” one is likely to notice things about the society that the society itself is not consciously aware of and which occur simply because that is the way it has “always” been. Anthropologists who are not enculturated can view a society dispassionately. They are able to ask questions that locals never ask. This makes it possible to identify why it is that people do what they do.

Cross-cultural studies are not only important to identify differences. They also enable anthropologists to identify similarities, enabling them to identify universals in being human.

Components of the Anthropological Perspective (2) – Holism

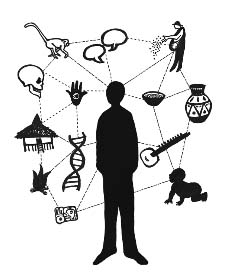

Anthropologists view culture as a complex web of interdependent and interconnected values, beliefs, traditions, and practices that shape the way people live and interact with one another. Each aspect of a society’s culture influences and interacts with other aspects of the same culture. Therefore, it is impossible to understand a culture in isolation or by examining individual elements in a piecemeal manner. This is why an anthropologist must consider all the components of the anthropological perspective.

When an anthropologist attempts to understand a culture, they must take into consideration the whole culture – its history, customs, language, religion, art, politics and economics – as well as the equilibrium between these different parts. This means that all aspects of the culture must be studied together to get a comprehensive understanding of how they work together to create a functioning society.

For example, an anthropologist studying a traditional agricultural community must examine not only the farming techniques used but also the social organization around agriculture including labour division and gender roles. In this way, one can see how farming practices are intertwined with cultural values such as family structure and social hierarchy, in a manner that makes sense in the environmental (for example fertile lands or arid desert) and historical context of the society.

When embarking on an ethnography the anthropologist must take account of each part of the equation or they risk misunderstanding the whole.

Economic Structure

When an anthropologist seeks to understand a culture, they must consider various aspects that influence the way people live and interact with each other. One important aspect is the economics of the culture. This includes examining the mode of production and the relations of production.

The mode of production refers to the way in which goods and services are produced within a society. For example, some societies may rely on subsistence agriculture while others may have industrialized economies with high levels of automation. The mode of production can have profound effects on social organization, power dynamics, and cultural values.

The relations of production refer to the social relationships that exist between people in regards to economic activities such as work and exchange. This includes examining issues such as labour division, property ownership, and access to resources. In some societies, these relationships may be based on kinship ties or communal ownership while in others they may be more individualistic or based on market relationships.

By understanding the economics of a culture, anthropologists gain an understanding of how people make a living, what resources are valued by society, and how wealth is distributed among different groups. They can also better understand how economic activities intersect with other aspects of culture such as religion, politics, and gender roles.

Kinship System

Another important aspect for consideration is the kinship system, which includes the system of descent , marriage practices, and living arrangements after marriage .

The system of descent refers to how people trace their ancestry and inheritance through their family tree. There are several different forms of descent systems such as patrilineal, matrilineal, and bilateral . These systems can have significant impacts on issues such as inheritance rights, social status, and gender roles .

Marriage practices also vary widely across cultures. Some societies practice arranged marriages while others allow individuals to choose their own partners. The rules around who can marry whom depend on factors such as age, social status, religion or ethnicity. Marriage practices may also have an impact on issues such as property ownership and inheritance.

Living arrangements after marriage can also vary widely across cultures . In some societies, newlyweds move in with one spouse’s family while in others they may establish their own household. The living arrangements of married couples can have an impact on issues such as gender roles within the family unit and the relationships between different generations.

By understanding the kinship system of a culture, anthropologists can gain insight into how families are organized and how social relationships are established within a society. They can also better understand how these relationships intersect with other aspects of culture such as religion, politics, and economics.

Religion, Beliefs and Rituals

Religion can be an important part of a culture’s identity and can shape many aspects of daily life. Different cultures may have different religious beliefs or practices, ranging from monotheistic religions such as Christianity or Islam to polytheistic religions such as Hinduism or Shintoism. Religion can also have an impact on issues such as gender roles, social hierarchy, and political power.

Beliefs are another important aspect of culture that anthropologists must consider. These beliefs may include ideas about the nature of reality, morality, and the afterlife. Beliefs shape how people view themselves and their place in society. They can also influence how people make decisions about issues such as health care or education.

Rituals are formalized behaviors that are typically associated with religious or cultural practices. Rituals may include things like prayer, meditation, or sacrifice. They often serve to reinforce social norms and values within a society while also providing individuals with a sense of community and belonging.

By understanding the religion, beliefs, and rituals of a culture, anthropologists can gain insight into how people understand their place in the world and how they relate to others within their society. They can also better understand how these beliefs intersect with other aspects of culture such as politics, economics, and gender roles.

Politics and Power

Politics refers to how a society is organized and who has power within that society. Different societies have different forms of government such as democracy , monarchy, or dictatorship. The balance of power between different groups within a society can also vary widely. Some societies may be hierarchically organized with clear social classes while others may be more egalitarian.

Understanding the political system of a culture can provide insights into issues such as social inequality, conflict resolution, and decision-making processes.

Anthropologists must also consider how political power is obtained and maintained within a society. This can include factors such as wealth, education, or military force.

Gender roles are another important aspect of culture that anthropologists must consider. These roles refer to the behaviours and expectations associated with being male or female in a given society. Gender roles can vary widely across cultures and may influence many aspects of daily life including work, family life, and social interactions. Understanding gender relations within a culture can provide insights into issues such as reproductive rights, violence against women, and access to education or employment opportunities.

Components of the Anthropological Perspective (3) – Cultural Relativism

This concept refers to the idea that when studying a different culture, an anthropologist must suspend their own cultural biases and avoid making value judgments about the beliefs and practices of the people they are studying.

Anthropologists recognize that every culture has its own unique set of values, beliefs, and practices that are shaped by historical, social, and environmental factors. These cultural differences can be difficult for outsiders to understand or accept, but it is important for anthropologists to approach other cultures with an open mind and without imposing their own cultural values on what they observe.

For example, an anthropologist studying a traditional society where arranged marriages are common may initially find this practice strange or even objectionable, based on their own cultural upbringing. However, in order to gain a deeper understanding of why arranged marriages are practiced in this society, the anthropologist must set aside their personal biases and seek to understand how this practice fits into the larger cultural context.

Cultural relativism does not mean that all cultural practices are equally valid or morally acceptable. Rather, it acknowledges that different cultures have different ways of understanding and interacting with the world around them. By approaching other cultures with an open mind and without preconceived notions or judgments, anthropologists can gain a deeper understanding of these differences while also recognizing universal human experiences such as love, loss, joy and pain.

In summary, cultural relativism is an essential component of the anthropological perspective. It requires anthropologists to approach other cultures with humility and respect while recognizing that every culture has its own unique set of values and beliefs shaped by historical, social and environmental factors. By embracing this perspective, anthropologists can gain deeper insights into what makes each culture unique while also recognizing shared human experiences across cultures.

Conclusion – The Importance of Considering all the Components of the Anthropological Perspective

The components of the anthropological perspective are crucial for understanding a culture in its entirety. Without taking these factors into consideration, an anthropologist’s understanding of a culture would be incomplete and may lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations.

Firstly, studying the politics and power dynamics within a society is important because it provides insights into how decisions are made and who holds influence over different aspects of daily life. This knowledge can help anthropologists understand issues such as social inequality, conflict resolution, and decision-making processes. By understanding the political system of a culture, an anthropologist can gain a deeper understanding of its structure and function.

Secondly, examining gender roles is important because it helps to shed light on how men and women interact with each other in different societies. Understanding gender relations within a culture provides insights into issues such as reproductive rights, violence against women, and access to education or employment opportunities. This knowledge can help anthropologists better understand how gender identity shapes individuals’ lives in different ways.

Finally, cultural relativism is essential for gaining an accurate understanding of another culture. It requires anthropologists to approach other cultures with humility and respect while recognizing that every culture has its own unique set of values and beliefs shaped by historical, social, and environmental factors. By embracing this perspective, anthropologists can avoid imposing their own cultural biases on their observations and instead seek to understand the beliefs and practices of the people they are studying on their own terms.

Overall, these three components of the anthropological perspective work together to provide a holistic view of a given culture. By keeping these components in mind when studying a culture, an anthropologist can gain a more complete picture of that society’s history, traditions, beliefs, practices and way of life over time.

Disclosure: Please note that some of the links in this post are affiliate links. When you use one of my affiliate links , the company compensates me. At no additional cost to you, I’ll earn a commission, which helps me run this blog and keep my in-depth content free of charge for all my readers.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Anthropological Perspective

The anthropological perspective is an incredibly complex and vast approach to our human civilization due to its holistic nature. The variety of research methods and subfields within anthropology are unique, as they often rely on scientific and humanistic disciplines to inquire about human nature. As such, the anthropological perspective reflects an overarching study of humanity, with a foundation in cultural relativism, fieldwork, scientific observation, data collection, and analysis.

Cultural relativism is vital to understanding diversity, social norms, and the origins of vastly different cultures. This is the current leading philosophy for many working anthropologists and is defined as an observation technique through which researchers understand a culture through the values of its population and not through their ideologies. This perspective seeks to reject ethnocentrism, judgment, and assumption of the inferiority of other cultures. Within the scope of research, ethnocentric perspectives are ineffective though most anthropologists, like other people, are always vulnerable to certain amounts of bias. Still, a culturally relativistic approach is essential in communication between individuals with differing backgrounds, values, and norms. As an example, the cultural shock and even discomfort that Elizabeth Warnock Fernea faced when assimilating to El Nahara, a remote village in Iraq, did not create an obstacle for her to understanding the local culture and lifestyle on a deeper level. Fernea approached the new environment without judgment and rejection, by participating in appropriate cultural and social activities such as housework, specific dress, and even learning Arabic (Warnock Fernea, 1995). Fernea’s Westernized values did not correlate with all local norms, such as the belief that not wearing a veil suggested immorality or lack of understanding of local customs translated to laziness and incompetence. As such, she may have disagreed with many aspects of local culture and lifestyle but approached the situation with cultural relativism. To create relationships with the women of the village, she assimilated to her best abilities and did not treat their culture and values as inferior or incorrect. This approach allowed her to formulate an informative study that would be much more surface level without the implementation of cultural relativism.

Though fieldwork may seem like an obvious aspect of the anthropological perspective, its effective utilization is vital to an informative and respectful study. The way an anthropologist approaches fieldwork dictates the depth of their understanding, the intricacies the subjects are willing to disclose, as well as a multitude of other factors that can contribute to the study. Most fieldwork is observation-based, with the researcher recording the day-to-day life of cultures, populations, and individuals for prolonged periods. Surveys, interviews, and questionnaires also become essential with informants and subjects, often steering the interviewer towards important aspects of their cultures, lifestyles, and societies. The result of the fieldwork can be referred to as ethnographies, accounts of a descriptive nature based on theory. Many of these accounts also bring further ethical dilemmas that anthropologists have to weigh, such as considering who may be adversely affected by the publication of the work, whether informants should be identified, or the resolution of the competing interests of the community and the funding agency. In the case of ‘In The Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio’, Phillipe Bourgois spent five years among Nuyorican crack dealers in East Harlem during the early years of the crack epidemic (Bourgois, 2003). Bourgeois was able to befriend people within the underground economy and crackhouses to such an extent that he came to observe the reasons why the youth are so susceptible to the criminal career path. Much of the interconnected social and economic factors were revealed to him through personal and seen cases of racism, historical colonialism, and inequality within the legal economy. His opportunity to have such a close view of the crisis may not have been possible without his involvement in his fieldwork. However, such deep understanding also allowed Bourgois to observe multiple ethical dilemmas in his work, such as the potential of negative stereotyping, elitist aspects of anthropology, and sensationalism of crime.

Within the field of anthropology, research merges both scientific and humanistic approaches to gathering data. Research may be deductive, like in the case of biological or archeological anthropology. It may also be inductive, such as in the study of language in which everyday language use may be collected and analyzed. Debates have divided anthropologists who utilize different research approaches, but anthropology is still widely considered a social science. Early 1800s analysis of indigenous groups living in the northern parts of North America was considered to be less advanced than other civilizations due to their continuing to live as hunter-gatherers (Spradley & McCurdy, 2012). This was because intelligence was associated with societal structure, with hunter-gatherers considered less intelligent than communities that relied on agriculture. However, such logic is flawed because it ignores many factors that influence the societal structure, such as the local ecology. The population of the northernmost areas is incredibly adaptive and inventive in terms of survival and long-term habitation. The very hostile area with limited plant life is exceptionally fitting for a community that is as well-prepared for it as indigenous groups are. In this case, a scientific approach, the assessment of local ecology, assisted with the realization that societal structure and intelligence are not directly related.

Bourgois, Phillipe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio . 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Spradley, James, and McCurdy, David W. Conflict and Conformity: Readings in Cultural Anthropology . 14th ed., Pearson Education, 2012.

Warnock Fernea, Elizabeth. Guests of the Sheik: An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village . Anchor, 1995.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, February 19). The Anthropological Perspective. https://studycorgi.com/the-anthropological-perspective/

"The Anthropological Perspective." StudyCorgi , 19 Feb. 2023, studycorgi.com/the-anthropological-perspective/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) 'The Anthropological Perspective'. 19 February.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Anthropological Perspective." February 19, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/the-anthropological-perspective/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Anthropological Perspective." February 19, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/the-anthropological-perspective/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "The Anthropological Perspective." February 19, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/the-anthropological-perspective/.

This paper, “The Anthropological Perspective”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 14, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Can Art Save the “Post-Apocalyptic” Salton Sea?

How Allocating Work Aided Our Evolutionary Success

Bringing Back the World’s Most Endangered Cat

The Shortcomings of Height in Politics

Griko’s Poetic Whisper

When a Message App Became Evidence of Terrorism

The Rise of Aunties in Pakistani Politics

For Families of Missing Loved Ones, Forensic Investigations Don’t Always Bring Closure

Albania’s Waste Collectors and the Fight for Dignity

Grappling With Guilt Inside a System of Structural Violence

Inside Russia’s Campaign to Steal and Indoctrinate Ukrainian Children

Coastal Eden

On the Tracks to Translating Indigenous Knowledge

A Call for Anthropological Poems of Resistance, Refusal, and Wayfinding

Buried in the Shadows, Ireland’s Unconsecrated Dead

Nameless Woman

A Palestinian Family’s History—Told Through Olive Trees

Can “Made in China” Become a Beacon of Sustainability?

The International Order Is Failing to Protect Palestinian Cultural Heritage

Spotlighting Black Women’s Mental Health Struggles

Being a “Good Man” in a Time of Climate Catastrophe

Cultivating Modern Farms Using Ancient Lessons

Imphal as a Pond

A Freediver Finds Belonging Without Breath

The Trauma Mantras

Baltimore’s Toxic Legacies Have Reached a Breaking Point

What a Community’s Mourning of an Owl Can Tell Us

Why I Talked to Pseudoarchaeologist Graham Hancock on Joe Rogan

Conflicting Times on the Camino de Santiago

Spotlighting War’s Cultural Destruction in Ukraine

Learning From Snapshots of Lost Fossils

How to Write an Essay: A Guide for Anthropologists

Ask SAPIENS is a series that offers a glimpse into the magazine’s inner workings.

For academics used to the idea of “publish or perish,” writing may seem to be a well-practiced and even perfected skill. But trying out a new writing style for a new audience—from crafting a tweet to penning an essay for the general public—can be an intimidating challenge, even for the most senior of professors.

If you’re struggling with this endeavor, then don’t despair. SAPIENS has a team of expert editors (including myself) with decades of experience wrangling the words of academics into insightful, clear, and interesting essays .

One of the most basic questions we’re asked at SAPIENS is: “How do I write an essay?” This article provides a framework and starting point.

There are two things you must know intimately before you start: your audience and your core point. Know these things and the rest will be far easier. Once you have locked down those two core elements, there’s a basic formula that you can master for almost any essay.

SAPIENS targets a general audience. Some of our readers are anthropologists, but most of them are not. Think of your reader as someone who is very intelligent but not knowledgeable in your area of expertise. Remember that even another anthropologist won’t necessarily know your subject area, the politics of your country or study sites, or the jargon of your specialty. Your essay should be full of depth and insight, providing new information and perspectives even to close colleagues, but it also needs to include basic background and context so that anyone can easily follow along.

A simple tip is to imagine that you are at a cocktail party and the conversation has turned to something you know a lot about. You want to inject some insight into the conversation. You want to thrill, delight, and inform the person you are talking to. That’s your job and the mood you should be in as you pick up your pen (or raise your fingers over the keyboard).

Remember that you are not writing an academic talk or paper or a grant proposal, where your primary mission may be to dive straight into the details, impress your colleagues or a panel of reviewers, or acknowledge others in the field. Buzzwords, jargon, and formal citations do not belong here.

SAPIENS readers are engaging with your essay not because they have to but because they want to. Grab their attention and hold on tight. As anthropologists know better than anyone, human beings have evolved to tell and listen to stories around the glow of a campfire. Harness this knowledge, and be sure you are telling a tale, complete with characters , tension , and surprises .

Anthropologists often have ethnographic research or a dig site to talk about: real people doing real things in real dirt. Pity the poor chemist who has less evocative characters like atoms and elements!

The next fundamental is to have a point. You may know a lot about a subject, but an essay needs to be more than just an overview of a topic. It needs to express a single (preferably surprising) viewpoint.

It should be possible to express the core of your main point in a single sentence containing a strong verb . To have a story, someone or something needs to be doing something: for example, battling a crisis , gaining an insight , identifying a problem , or answering a question . This statement may even become the headline for your essay. An op-ed , by the way, is a very similar beast to an essay, but its point is by definition an expression of what’s wrong with the world and how to fix it.

Once you know what you’re writing and for whom, you can write.

A strong essay contains some basic elements.

A colleague of mine once observed that writing is like certain styles of jazz: The improvisation is layered on top of some standard rules in order to make something beautiful. Until you master the basics, it’s safer to follow straightforward strategies in order to avoid accidentally playing something jarring and incomprehensible.

In keeping with the musical theme, I offer seven notes to play in your piece.

One: A lead.

This paragraph opens your essay. It needs to grab the reader’s attention. You can use an anecdote , a story , or a shocking fact . Paint a picture to put the reader in a special time and place with you.

Resist the temptation to rely on stereotypes or often-used scenes. Provide something novel and compelling.

Two: A nut paragraph.

This section captures your point in a nutshell. It usually repeats the gist of what your headline will capture but expands on it a little bit. A good nut paragraph (or “ nutgraf ,” to use some journalist jargon) is a great help for your reader. It’s like a signpost to let them know what’s coming, providing both a sense of security and of anticipation, which can make them willing to come on this journey with you over the next thousand words.

The nut is often the most important paragraph but also sometimes the hardest nut to crack. If you can write this paragraph, the rest will be easy. (The nut for this piece is the fourth paragraph; in the essay “ Trump’s Slogan ,” it’s the third.)

Remember to include in your nut, or somewhere near it, a “peg”: some real-world event that you can hang your essay on, like hanging your coat on a hook on the wall, to place it firmly in time and space. Does your point relate to something going on in the world, such as the Black Lives Matter movement , a policy change, a new archaeological dig or museum object —or maybe a pandemic ? Does it relate to a holiday , such as Halloween , or a season ? Did you recently publish a paper or a book on the topic? Why should your reader read on right now ?

Three: Who you are.

Let your reader know what you are an expert in, what you have done that makes you an expert, and why they should put faith in your point of view.

Your byline will link to biographical information that declares you are an anthropologist of such-and-such variety at so-and-so university or institute, but the essay itself should spell out that you have, for example, spent decades among a certain community or surveyed hundreds of people affected by an issue. Sometimes your own personal details—your race , your nationality , your heritage , your lived experiences —may also play into your expertise or story. (See how I snuck my own expertise into the second paragraph of this piece.)

Four: Background and context.

After the opening section, your essay’s pace can slow a little. Tell the reader a bit more about the situation, place, insight, or people you are writing about. What’s the history? How did things get to be the way they are? Why does this situation, place, or finding matter to the rest of the world? Why is it important, and why are you personally so interested in it?

Don’t wander too far along the way: Each paragraph should continue to speak to and support your main point. It’s an essay, not a book. Keep it simple.

Five: The details.

Expand on your point. Provide details, facts, anecdotes, or evidence to back up your point and tell a story. Perhaps you have quotes from people you interviewed or statistics behind some aspect of medical anthropology. Those details are the meat of your piece. What insight can you provide?

Back up your view with facts, and provide links to firm evidence (such as published research papers, by yourself or others) supporting any assertions. Sprinkle in an occasional short, pithy sentence to hammer your point home.

Six: Counterpoint.

If your point of view is contentious, acknowledge that. Let the reader know which groups disagree with you and why, and what your counterarguments are.

This approach will add to your credibility. If your point rubs up against what most readers will think, then acknowledge that too. Anticipate common reactions and deal with them head on.

Seven: Conclusion.

Round up your point, sum up your argument, or perhaps look forward to what needs to be done next. (But please don’t simply say, “More research is needed,” which is always true and too broad to provide helpful insight.) Leave your reader with a sense of satisfaction rather than a craving for more or a feeling of confusion.

Sometimes it is nice to have a final point that ends your piece with a bit of a kick. If your essay is amusing, this “kicker” might be designed to make the reader laugh . If it’s discussing a serious societal problem, it might hammer home what’s at stake. If your essay is personal or reflective, it might be an experience that crystallizes your point . For an op-ed, it may be a call to arms .

An essay as a whole should say to the reader, “Look at the world through my eyes, and you will see something new.” Your goal is to enlighten in a clear, entertaining way.

Your editor’s job, by the way, is to help you do all of this: to formulate your point as clearly and strongly as possible, and to prompt you for an anecdote or story to make that point come alive. Your editor’s job is not to mangle your ideas or force you onto uncomfortable ground, nor is it to put things in ways you would not say them or make your voice unrecognizable. If that happens, be sure to speak up.

Remember that if your editor is misunderstanding your text, your readers will surely misunderstand it too. If your editor trips on a point, or stumbles on your phrasing, so will your readers. Editors are experts at identifying problems in a piece but not necessarily experts on how to fix them—make that your job.

Many, many subtle points of writing exist beyond what I have included in this guide. The interested writer may wish to read a slender book packed with fantastic advice: The Science Writers’ Essay Handbook: How to Craft Compelling True Stories in Any Medium .

And there are some considerations that are particular to, or prominent in, anthropological writing—such as the ethical presentation and protection of your sources and the importance of original writing even when retelling the same tales you have published before. Your editors can help you address all of these challenges.

Writing for the general public comes with many benefits. It helps convince funders and university deans that your area of interest is important. It may count toward your application for tenure or raise the profile of your institution. Perhaps most importantly, it can help strengthen your own writing and clarify your ideas in your own mind—cementing your conclusions or spurring ideas for further research. Stepping away from your usual audience, methods, and ways of thinking is a great way to gain novel insights.

Writing for the public brings your important ideas to the wider world and may even help change that world for the better.

You surely have something important to say: Write it for us !

Nicola Jones is a freelance science journalist living in Pemberton, near Vancouver, British Columbia. She has a bachelor’s degree in oceanography and chemistry, and a master’s in journalism, both from the University of British Columbia. Over her career, Jones has been a regular editor and contributor to SAPIENS , Nature , Yale Environment 360 , Hakai Magazine , Knowable Magazine , and other publications. She has given a TED Talk and edited a major report for Future Earth on sustainability. Follow her on Twitter @nicolakimjones .

Stay connected

Facebook , Instagram , LinkedIn , Threads , Twitter , Mastodon , Flipboard

Y ou may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

I n short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on SAPIENS.

A ccompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

We’re glad you enjoyed the article! Want to republish it?

This article is currently copyrighted to SAPIENS and the author. But, we love to spread anthropology around the internet and beyond. Please send your republication request via email to editor•sapiens.org.

Accompanying photos are not included in any republishing agreement; requests to republish photos must be made directly to the copyright holder.

Anthropology

What this handout is about.

This handout briefly situates anthropology as a discipline of study within the social sciences. It provides an introduction to the kinds of writing that you might encounter in your anthropology courses, describes some of the expectations that your instructors may have, and suggests some ways to approach your assignments. It also includes links to information on citation practices in anthropology and resources for writing anthropological research papers.

What is anthropology, and what do anthropologists study?

Anthropology is the study of human groups and cultures, both past and present. Anthropology shares this focus on the study of human groups with other social science disciplines like political science, sociology, and economics. What makes anthropology unique is its commitment to examining claims about human ‘nature’ using a four-field approach. The four major subfields within anthropology are linguistic anthropology, socio-cultural anthropology (sometimes called ethnology), archaeology, and physical anthropology. Each of these subfields takes a different approach to the study of humans; together, they provide a holistic view. So, for example, physical anthropologists are interested in humans as an evolving biological species. Linguistic anthropologists are concerned with the physical and historical development of human language, as well as contemporary issues related to culture and language. Archaeologists examine human cultures of the past through systematic examinations of artifactual evidence. And cultural anthropologists study contemporary human groups or cultures.

What kinds of writing assignments might I encounter in my anthropology courses?

The types of writing that you do in your anthropology course will depend on your instructor’s learning and writing goals for the class, as well as which subfield of anthropology you are studying. Each writing exercise is intended to help you to develop particular skills. Most introductory and intermediate level anthropology writing assignments ask for a critical assessment of a group of readings, course lectures, or concepts. Here are three common types of anthropology writing assignments:

Critical essays

This is the type of assignment most often given in anthropology courses (and many other college courses). Your anthropology courses will often require you to evaluate how successfully or persuasively a particular anthropological theory addresses, explains, or illuminates a particular ethnographic or archaeological example. When your instructor tells you to “argue,” “evaluate,” or “assess,” they are probably asking for some sort of critical essay. (For more help with deciphering your assignments, see our handout on understanding assignments .)

Writing a “critical” essay does not mean focusing only on the most negative aspects of a particular reading or theory. Instead, a critical essay should evaluate or assess both the weaknesses and the merits of a given set of readings, theories, methods, or arguments.

Sample assignment:

Assess the cultural evolutionary ideas of late 19th century anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan in terms of recent anthropological writings on globalization (select one recent author to compare with Morgan). What kinds of anthropological concerns or questions did Morgan have? What kinds of anthropological concerns underlie the current anthropological work on globalization that you have selected? And what assumptions, theoretical frameworks, and methodologies inform these questions or projects?

Ethnographic projects

Another common type of research and writing activity in anthropology is the ethnographic assignment. Your anthropology instructor might expect you to engage in a semester-long ethnographic project or something shorter and less involved (for example, a two-week mini-ethnography).

So what is an ethnography? “Ethnography” means, literally, a portrait (graph) of a group of people (ethnos). An ethnography is a social, political, and/or historical portrait of a particular group of people or a particular situation or practice, at a particular period in time, and within a particular context or space. Ethnographies have traditionally been based on an anthropologist’s long-term, firsthand research (called fieldwork) in the place and among the people or activities they are studying. If your instructor asks you to do an ethnographic project, that project will likely require some fieldwork.

Because they are so important to anthropological writing and because they may be an unfamiliar form for many writers, ethnographies will be described in more detail later in this handout.

Spend two hours riding the Chapel Hill Transit bus. Take detailed notes on your observations, documenting the setting of your fieldwork, the time of day or night during which you observed and anything that you feel will help paint a picture of your experience. For example, how many people were on the bus? Which route was it? What time? How did the bus smell? What kinds of things did you see while you were riding? What did people do while riding? Where were people going? Did people talk? What did they say? What were people doing? Did anything happen that seemed unusual, ordinary, or interesting to you? Why? Write down any thoughts, self-reflections, and reactions you have during your two hours of fieldwork. At the end of your observation period, type up your fieldnotes, including your personal thoughts (labeling them as such to separate them from your more descriptive notes). Then write a reflective response about your experience that answers this question: how is riding a bus about more than transportation?

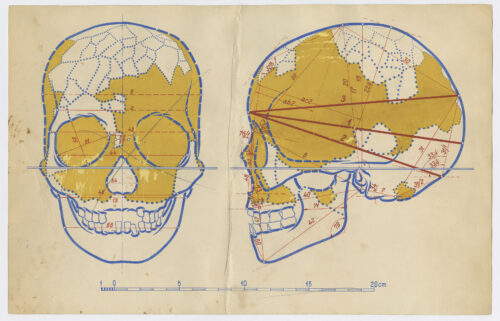

Analyses using fossil and material evidence

In some assignments, you might be asked to evaluate the claims different researchers have made about the emergence and effects of particular human phenomena, such as the advantages of bipedalism, the origins of agriculture, or the appearance of human language. To complete these assignments, you must understand and evaluate the claims being made by the authors of the sources you are reading, as well as the fossil or material evidence used to support those claims. Fossil evidence might include things like carbon dated bone remains; material evidence might include things like stone tools or pottery shards. You will usually learn about these kinds of evidence by reviewing scholarly studies, course readings, and photographs, rather than by studying fossils and artifacts directly.

The emergence of bipedalism (the ability to walk on two feet) is considered one of the most important adaptive shifts in the evolution of the human species, but its origins in space and time are debated. Using course materials and outside readings, examine three authors’ hypotheses for the origins of bipedalism. Compare the supporting points (such as fossil evidence and experimental data) that each author uses to support their claims. Based on your examination of the claims and the supporting data being used, construct an argument for why you think bipedal locomotion emerged where and when it did.

How should I approach anthropology papers?

Writing an essay in anthropology is very similar to writing an argumentative essay in other disciplines. In most cases, the only difference is in the kind of evidence you use to support your argument. In an English essay, you might use textual evidence from novels or literary theory to support your claims; in an anthropology essay, you will most often be using textual evidence from ethnographies, artifactual evidence, or other support from anthropological theories to make your arguments.

Here are some tips for approaching your anthropology writing assignments:

- Make sure that you understand what the prompt or question is asking you to do. It is a good idea to consult with your instructor or teaching assistant if the prompt is unclear to you. See our handout on arguments and handout on college writing for help understanding what many college instructors look for in a typical paper.

- Review the materials that you will be writing with and about. One way to start is to set aside the readings or lecture notes that are not relevant to the argument you will make in your paper. This will help you focus on the most important arguments, issues, and behavioral and/or material data that you will be critically assessing. Once you have reviewed your evidence and course materials, you might decide to have a brainstorming session. Our handouts on reading in preparation for writing and brainstorming might be useful for you at this point.

- Develop a working thesis and begin to organize your evidence (class lectures, texts, research materials) to support it. Our handouts on constructing thesis statements and paragraph development will help you generate a thesis and develop your ideas and arguments into clearly defined paragraphs.

What is an ethnography? What is ethnographic evidence?

Many introductory anthropology courses involve reading and evaluating a particular kind of text called an ethnography. To understand and assess ethnographies, you will need to know what counts as ethnographic data or evidence.

You’ll recall from earlier in this handout that an ethnography is a portrait—a description of a particular human situation, practice, or group as it exists (or existed) in a particular time, at a particular place, etc. So what kinds of things might be used as evidence or data in an ethnography (or in your discussion of an ethnography someone else has written)? Here are a few of the most common:

- Things said by informants (people who are being studied or interviewed). When you are trying to illustrate someone’s point of view, it is very helpful to appeal to their own words. In addition to using verbatim excerpts taken from interviews, you can also paraphrase an informant’s response to a particular question.

- Observations and descriptions of events, human activities, behaviors, or situations.

- Relevant historical background information.

- Statistical data.

Remember that “evidence” is not something that exists on its own. A fact or observation becomes evidence when it is clearly connected to an argument in order to support that argument. It is your job to help your reader understand the connection you are making: you must clearly explain why statements x, y, and z are evidence for a particular claim and why they are important to your overall claim or position.

Citation practices in anthropology

In anthropology, as in other fields of study, it is very important that you cite the sources that you use to form and articulate your ideas. (Please refer to our handout on plagiarism for information on how to avoid plagiarizing). Anthropologists follow the Chicago Manual of Style when they document their sources. The basic rules for anthropological citation practices can be found in the AAA (American Anthropological Association) Style Guide. Note that anthropologists generally use in-text citations, rather than footnotes. This means that when you are using someone else’s ideas (whether it’s a word-for-word quote or something you have restated in your own words), you should include the author’s last name and the date the source text was published in parentheses at the end of the sentence, like this: (Author 1983).

If your anthropology or archaeology instructor asks you to follow the style requirements of a particular academic journal, the journal’s website should contain the information you will need to format your citations. Examples of such journals include The American Journal of Physical Anthropology and American Antiquity . If the style requirements for a particular journal are not explicitly stated, many instructors will be satisfied if you consistently use the citation style of your choice.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Scupin, Raymond, and Christopher DeCorse. 2016. Anthropology: A Global Perspective , 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Solis, Jacqueline. 2020. “A to Z Databases: Anthropology.” Subject Research Guides, University of North Carolina. Last updated November 2, 2020. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/az.php?s=1107 .

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Anthropology Essay Examples

10+ Anthropology Essay Examples & Topics to Kick-Start Your Writing

Published on: May 5, 2023

Last updated on: Aug 21, 2024

Share this article

Are you a student looking for inspiration for your next anthropology essay?

With so many subfields, it's easy to feel overwhelmed and unsure of what to focus on. You want to create an essay that is not only informative but also engaging and thought-provoking. You want to stand out from the crowd and make a lasting impression on your readers.

But how do you achieve that when you're not even sure where to start from?

Don't worry, we've got you covered.

In this blog, we've compiled a collection of some of the best anthropology essay examples to help you get started. We will also provide you with a list of topics you can choose from!

So get ready to dive into the rich and complex world of anthropology through these essays.

On This Page On This Page -->

What is an Anthropology Essay?

Anthropology is the study of human societies and cultures. An anthropology essay is an academic paper that explores various aspects of this field.

The goal of an anthropology essay is to analyze the practices of human beings in different parts of the world. Check out this anthropology essay example for a better understanding:

Anthropology Essay Pdf

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Anthropology Essay Examples for Students

Writing an anthropology essay can be a daunting task, especially if you're not sure where to start.

Letâs explore these anthropology essay examples for some captivating ideas.

Anthropology College Essay Examples

Anthropology Research Paper Example

Anthropology Essay Examples on Different Subjects

Anthropology is a vast field with many subfields and topics to explore. As a student, it can be challenging to navigate this diverse landscape and find a subject that interests you.

In this section, we've compiled a list of anthropology paper examples for different subjects to help you get started.

What Makes Us Human Anthropology Essay

Social Anthropology Essay

Cultural Anthropology Essay

What I Learned In Anthropology Essay

Social And Cultural Anthropology Extended Essay Example

Anthropology Essay Format

The format of an anthropology essay can vary depending on the assignment requirements. But generally, it follows a standard structure.

Learn how to write an anthropology essay here:

Introduction

A catchy introduction provides background information on your topic and presents your thesis statement.

Check out this introduction example to help you craft yours!

Anthropology Introduction Essay Example

Body paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you develop your argument in a series of paragraphs. Each focuses on a specific idea or argument.

Make sure to support each argument with evidence from your research.

Learn to write a body paragraph with the help of this example:

Anthropology Body Paragraph Essay Example

The conclusion of an essay summarizes the main points and restates your thesis statement. Always end your essay with a thought-provoking statement or call to action.

Want an example of how to conclude your anthropology essay? Here is an example:

Anthropology Conclusion Essay Example

Anthropology Essay Topics

It's essential to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field.

Here are some anthropology essay topics to consider:

- The cultural significance of rituals and ceremonies

- The impact of globalization on traditional societies

- The evolution of human communication and language

- The social and cultural implications of technology

- The role of gender and sexuality in different cultures

- The relationship between culture and power

- The impact of colonialism on indigenous cultures

- The cultural significance of food and cuisine

- The effects of climate change on human societies

- The ethics of anthropological research and representation.

All in all, anthropology essays require critical thinking, research, and an understanding of diverse cultures and societies.

With the examples and the right AI essay writing tools , you can craft a compelling essay that showcases insights into the field of anthropology.

If you're feeling overwhelmed or need support, our anthropology essay writing service will ease the process for you.

Don't let the challenges of writing an anthropology essay hold you back! Just ask us, â write my college essay for me â and we'll help you succeed!

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some common mistakes to avoid when writing an anthropology essay.

Common mistakes to avoid when writing an anthropology essay include:

- Using jargon without defining it

- Neglecting to engage with relevant literature

- Failing to provide sufficient evidence to support your claims

Are there any ethical considerations to keep in mind when conducting anthropological research?

Yes, ethical considerations are crucial in anthropological research. Researchers must obtain informed consent from participants and ensure that their research does not cause harm.

Cathy A. (Literature)

For more than five years now, Cathy has been one of our most hardworking authors on the platform. With a Masters degree in mass communication, she knows the ins and outs of professional writing. Clients often leave her glowing reviews for being an amazing writer who takes her work very seriously.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question of the Month

Who or what am i, the following answers to the question of the self each win a random book..

I am a living, breathing organism signified by the words ‘human being’. I am a material or physical being fairly recognisable over time to me and to others: I am a body. Through my body, I can move, touch, see, hear, taste and smell. The array of physical sensations available to me also includes pain, hunger, thirst, tiredness, injury, sickness, fear, apprehension and pleasure. In this way I experience myself, others and the world around me. However, there is another aspect of me not directly visible or definable. This is the aspect of me which thinks and feels, reflects and judges, remembers and anticipates. Words used to describe this aspect include ‘mind’, ‘spirit’, ‘heart’, ‘soul’, ‘awareness’ and ‘consciousness’. This part of me is aware that I can never be fully known or understood by myself or by others; it notices that although there may be some unchanging essence which is ‘me’, this same ‘me’ is also constantly changing and evolving.

So I am a physical body and an emotional and psychological (or spiritual) being. The two together make me a person. Being a person means that I have virtues and flaws, gifts and needs, possibilities and defeats. I am basically good, but I am capable of evil. I am neither an angel nor a monster. Being a person means that I am a social animal, needing connection, recognition and acceptance from others, while simultaneously knowing myself as isolated and solitary, with many experiences which are never fully shareable with others. However, I also realise that this paradoxical condition is a universal experience, and this enables the emergence of empathy and compassion for others as it affords glimpses of understanding and solicitude, mutuality and intimacy. Being a person means that I am like all other persons, but also unique. It also means that I can never provide a genuinely definitive answer to the question.

Kathleen O’Dwyer, Limerick, Ireland

Human beings are defined by a sense of personality, experiences and reason. We are often inclined to believe that the face we see in the mirror is us, a thing which has developed a personality through experiences. Here the body is merely a tool for the true self, the mind. It is however an error to conclude that the body is not significant for selfhood. Without a body a mind would not be able to make certain types of judgments.

The mind/brain utilizes the body to survive, calculate and function within various social contexts. It also favors order rather than chaos. The mind governing our body assigns mental places to various objects in the world. Through the use of language humanity has come to construct an image of the world that transcends one’s own immediate environment. This has enabled humans to develop complex means of social interaction. Thus we are physical beings capable of having non-physical thoughts that in turn construct and sometimes deconstruct the physical world .

David Tamez, Austin, TX

I would argue that the answer to this question is dependent on the idea of identity. The idea of identity is itself rather problematic in that it’s determined from subjective viewpoints, which can be divided into two types. The first is an internal creation of identity, formed by myself for myself. This is the picture I have of myself. The second is an external creation of identity, formed by someone else. These are the pictures that other people have of me. “I am a fool!” cries the self, while the other labels that person a genius (or vice versa ). Inevitably there will be clashes based on differing viewpoints. While not always so extreme as this example, it must surely be very rare that people will agree entirely on a person’s identity. In the same way that Einstein showed that time is dependant on viewpoint, so I think we can show that identity is relative, and by extension, the answer to the question ‘Who or what am I?’ becomes a matter of who is answering it. The question must then be asked, on what do we base these identities we assign other people or ourselves? It seems that assigning a particular identity to someone else occurs through a process of observation, watching and remembering a person’s actions, then placing a value on the information we have of that person from our past and present encounters. Our view of our own identity places the highest priority on the intentions and thoughts that precede our actions, in contrast to other people’s reliance on our actions. This can mean that the person we consider ourselves to be may not be the person we portray to others.

Anoosh Falak Rafat, Erith, Kent

Philosophy is about generalities, but this question demands particularity: who am I – a particular person in a particular time and place, related in particular ways to others? The usual answers are not of much philosophical interest: Bill, Patricia’s husband, Katy’s father. In each of these identities, however, I find two things: a state of interiority – feelings, thoughts, beliefs and desires with which only I am directly acquainted, and a social role – a relatedness to other human beings. So the question is two-fold: How does it feel to be me? and How do I function in a social context? Each of us must answer these questions for ourselves, but we can share our answers with others. The first-person point of view is an important starting point. We each have a life-story, of what has been and continues to be important to us, what the pivotal events were that brought us to the present moment. By comparing stories, we find such timeless human themes as love and hate, honor and degradation, loyalty and betrayal, inspiration and despair; and we learn how others have handled themselves in situations without ourselves having to undergo them. In this way human culture advances far more rapidly than biological evolution. By taking an ‘objective’ point of view toward our own subjectivity, we can transcend ourselves. We are not bound by chains of habit or instinct; we can see who we are and choose to change it. The ability to examine one’s own experience is something that distinguishes us from other animals. We have, in some measure, the ability to create ourselves. There are limits to what we can make of ourselves imposed by evolution, biology and culture, ut the ability to know those limits and find ways to work within them gives us the unique ability not only to discover, but to decide and create the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’

Bill Meacham, Austin, TX

If you look in the mirror, what is staring back at you? Flesh. Eyes. And underneath that? Bones. Blood. Brain. But then, what makes us different from animals? Is it, with Plato and Aristotle, the ability to reason and live virtuously? Possibly – so a soul, a consciousness. It is perfectly likely that our one defining feature is metaphysical. But higher mammals’ intelligence is too near ours to assume this is our single differentiation: the ability to communicate and love is reflected in dolphins and primates. So it is equally likely that being human comes down to our biological structure – our DNA and physiology – developing certain features that other animals lack, including hormones. Perhaps what we really are comes down to the rather annoying answer, “we are human.” But ‘human’ describes something that we cannot certainly define or grasp. The most we can do is ascertain that we are indeed different, a compilation of our multiplicity: we are evolved animals; the inhabitants of earth; the most widespread of colonists, and the most diverse of species. And when we look in the mirror, to question ourselves and stare at our flesh, our eyes, our bones, our blood, to philosophise and obey our brains – in short, when we define ourselves as human, that is what it is to be a person.

Amy Andrews, Nantwich, Cheshire

Half of our lives we behave like animals. Sleeping, feeding, drinking, pursuing sex and other bodily necessities, we do exactly what baboons, monkeys, and other animals do. Most of the rest of our available time is spend doing what the societies we live in want us to do, namely work to earn enough to pay for those necessities. The little time left over which we could call ‘time out’ is scarcely enough to keep up with what happens in the world around us, if we even are interested.

When I look at the mirror in the morning, the face which stares back at me is not me. It cannot be me, it is too old to be me. I am retired a long time already, and we all change considerably through the years. I call it an evolutionary process; but still, this face I see does not correspond with what I feel I am.

I am still looking for what Martin Heidegger called ‘Being’. I follow his idea about Dasein . Even living 50% of the time as an ape, I nevertheless feel the facticity of living in space and time, and have always tried to be authentic in my acts and the thoughts which motivate them, seeking an independence of mind and avoiding the general entrapment of following the crowd in the search for the Being of beings. I still consider it a lucky fact to have been ‘thrown into’ a world which is no doubt hostile, repetitive and extremely materialistic, and have accepted nothingness as the ultimate destination of my journey, yet I’m still asking the question ‘why is there something rather than nothing?’ I thought about all of this when I was a young man, and the answer to this question and so many other ones are still out of my reach, and the doubts about meaning of life permeate my mind today as strongly as when I was a student opening my eyes to the basic questions of Being. If this is so, why don’t I know the face in the mirror?

Henry Back, Flagler Beach, Florida

The question ‘Who am I?’ can be answered only specifically. Anything else would be an abstraction that would liken me to others who share such characteristics. But that’s not who I am, that’s what I am. So here is a description of who I am in particular contexts. When I walk in the park, I am Friendly Human. I adopt a stance toward others of smiling, looking at them rather than averting my eyes, nodding and saying “Hello” and so forth. Doing so helps me feel safe and connected with them. Friendly Human is a strategy for being in the world which avoids hostility and harm. It includes deference and yielding. I step aside when encountering someone on a narrow path. By letting them pass, I avoid confrontation and disharmony. I get more enjoyment from the path by letting others have it. They pass, and I get to continue to meander as I wish. When I am Friendly Human I am not Worker, focused on accomplishing a task. I am not Competitor, focused on getting somewhere ahead of someone else. I am not Acquisitor, focused on getting what I want. Nor am I Intimate, focused on loving, understanding and enjoying my mate. I am just Friendly Human – a bit like a dog, but with more autonomy. Worker has a sense of self-importance, pleasure at doing something worthwhile, sometimes angry at obstacles, sometimes pleased at accomplishment. Competitor feels tense, anxious and angry. Acquisitor feels much like Worker, but when combined with Competitor, feels hostile. Intimate feels best of all. When I am Intimate, my guard is down; I delight in things my mate does; I let my thoughts and words flow freely; I bask in the warmth of love. By contrast, Friendly Human is peaceful and relaxed but a bit reserved: I am not anxious, angry or hostile, but neither am I completely unguarded. I keep to myself, engaging others briefly if they wish, or not at all. There is philosophical interest in this only to the extent that it illustrates the human capacity to adopt strategies for being in the world, and thereby define our own answers to the question ‘Who am I?’

Robert Tables, Blanco, TX

I’m a crowd, so I’m a ‘what’. There isn’t an ‘I’. As psychosynthesis says, I’m a collection of sub-personalities. More accurately, this thing is a collection of personalities, some shy, some noisy, pushy, sexy, boring, clever. This is the Many Selves model. The Gestalt view is similar: I/This is the continuous interaction and interrelatedness between myself and the environment of others and objects. Except on this theory there isn’t a ‘myself’ at the core, this I-ness is the constant flux. Even when alone, eyes closed in silence, there’s the flux of sensations and thoughts (coming from where?) In the Many Selves model all these Selves are interrelated, actors with a script they write as the play proceeds, with more parts than actors, so multiple roles are played. The problem is that, mostly we want to believe there is a core self or single I inside the sensations, so we can reinforce our Self Concept: “I am the sort of person who…” A fragmented self-concept is emotionally distressing.

I see the Self as a kaleidoscope. As with the Gestalt and the Many Selves models, the pattern is ever changing. Life and its activities is rotating the kaleidoscope, rather than me. My very limited control is to speed it up or slow it down. The constant ‘me’ I wake up as is the kaleidoscope briefly at rest before the environment begins to turn it. The kaleidoscope’s glitter are the few fixed aspects of me, such as gender, body, culture, etc. What’s new every time is the mood I wake up in or experience. Differences between people are simply different combinations of different bits. His bits are mainly red and angular – a spiky person; hers are mostly greenish and rounded, a softer personality. To a degree I can add or remove bits of glitter, choosing colour and shape, such as changing my behaviours and attitudes. But, as with a real kaleidoscope, this means opening up and getting inside, which we mostly resist. So I cannot say “I am.” I can only say “This thing I call Myself is like the image in rotating kaleidoscope” and “I am a Crowd.”

Tony Morris, Putney, London

To answer this question requires gaining some perspective on oneself. Not capable of devouring huge quantities of texts on Descartes’ cogito , Freud’s ego , Proust’s ‘true me’, Sartre’s ‘non-essence’ or Locke’s personal identity, I choose a different approach, related to a condition I have had since my teenage years: depersonalisation. For those of you unfamiliar with the disorder, it involves losing a sense of self – failing to recognise any physical connection with your own body. Sufferers regularly experience autoscopy, more commonly known as an out-of-body experience. A common technique for getting back in is to list the five senses and write what you are experiencing for each one, hopefully reconnecting yourself with yourself in the process. In more extreme cases sufferers have been known to self-harm, acute pain creating a faster and stronger reconnection.

When I am in a depersonalised state I know two things. First, I know that my physical body can function without my mind being in control, as I can observe this occurring. The body runs on the mind’s residuum. Second, as mentioned, I know that to reconnect I must experience a physical sensation, painful or pleasurable, the more intense the more effective. From this I can deduce that there are two entities present, the conscious and the physical, and the link that connects the two is sensation. So for me, the ‘Who’ is the consciousness and the ‘What’ is the body. But are we still the same person if we suffer from some degenerate disease, mental or physical? I’d like to end with a Joyce quote, which could shed more light on the problem than I have: “I am tomorrow, or some future day, what I establish today. I am today what I established yesterday or some previous day.”

S. E. Smith, Lancaster

I’m a book. Not literally, of course, but this is the metaphor that I’m going to use, so please bear with me.

I am a particular self. So, what makes a self particular? Its story. That is, the events and objects surrounding it, and its actions on, reactions to, and perceptions of them. You are you because you have lived your life, and I am me because I have lived mine. Even if I had a Siamese Clone we would still have different selves because he would perceive the world from a different viewpoint than me. An important aspect of this story about stories is that the story exists independently of me.

This means that I am a self plus a story. The situation is comparable to that of a book. Books have similar physical elements, like paper, binding, and ink. What makes them unique is the story that they contain. Even if The Iliad has the same font, paper, and glue as El Otoño del Patriarca , they are different books because one is about a Greek struggle and the other a Latin dictator. Likewise, I am different from you because my story is about a guy from Edmond and yours is not. And there you have it. You, me, the creepy guy down the hall – we all have similar selves, but I’m a one-of-a-kind story.

Matthew Hewes, Edmond, OK

I share a large genetic similarity with mice. And like mice I am also made of water and soil. Yet I have opposable thumbs and use language, narratives and imagination for almost everything in life. Because of all that, I think myself superior to a mouse. If I were like most humans I would carry that thought even further, and think that I was either the pinnacle of evolutionary development or the crowning achievement of a divine being’s creation, only slightly less divine than the supernatural being who created me. However, personally, I think none of those grand thoughts. I am a water molecule in an ocean. I am a grain of sand on a beach. I am a linguistic phrase in the novel of time. I am a “ha!” in the middle of a long belly laugh. And these thoughts are more comfortable, less stressful views of me than grand visions of me as the center and purpose of everything. I am a part of everything, but I am not in charge of everything, and that’s a relief. I’m here to do as best I can: my watery, grainy, languagey part of the story society is constantly creating about what it means to be alive. Towards that end I am a thought collector, and I hoard ideas and experiences like a mouse hoards cheese. From my collection I create a story, and with my opposable thumbs and language skills I share it.

Sue Clancy, Norman, Oklahoma

I want to answer your question by paraphrasing the originator of Psychosynthesis, Roberto Assagioli:

I have a body, but I am not my body.

I have emotions, but I am not my emotions.

I have a mind, but I am not my mind.

I have roles to play in life, but I am not any of them.

I am a centre of pure consciousness.

Ray Sherman, Duarte, CA

Next Question of the Month

To celebrate the launch of Mark Vernon’s book How To Be An Agnostic (Palgrave Macmillan) the next question of the month is: What is Truth? The prize is a signed copy of the book. Let us know what truth is and what it’s good for in less than 400 words, please. Subject lines or envelopes should be marked ‘Question Of The Month’, and must be received by 25th July. If you want a chance of getting a signed book, please include your physical address. Submission implies permission to reproduce your answer physically and electronically.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)