The climate crisis, migration, and refugees

- Download the policy brief

Subscribe to Global Connection

John podesta john podesta founder and director - the center for american progress.

July 25, 2019

- 18 min read

The following is one of eight briefs commissioned for the 16th annual Brookings Blum Roundtable, “2020 and beyond: Maintaining the bipartisan narrative on US global development.”

On March 14, 2019, Tropical Cyclone Idai struck the southeast coast of Mozambique. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees reported that 1.85 million people needed assistance. 146,000 people were internally displaced, and Mozambique scrambled to house them in 155 temporary sites. 1 The cyclone and subsequent flooding damaged 100,000 homes, destroyed 1 million acres of crops, and demolished $1 billion worth of infrastructure. 2

One historic storm in one place over the course of one day. While Cyclone Idai was the worst storm in Mozambique’s history, the world is looking towards a future where these “unprecedented” storms are commonplace. This global challenge has and will continue to create a multitude of critical issues that the international community must confront, including:

- Large-scale human migration due to resource scarcity, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and other factors, particularly in the developing countries in the earth’s low latitudinal band

- Intensifying intra- and inter-state competition for food, water, and other resources, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa

- Increased frequency and severity of disease outbreaks

- Increased U.S. border stress due to the severe effects of climate change in parts of Central America

All of these challenges are serious, but the scope and scale of human migration due to climate change will test the limits of national and global governance as well as international cooperation.

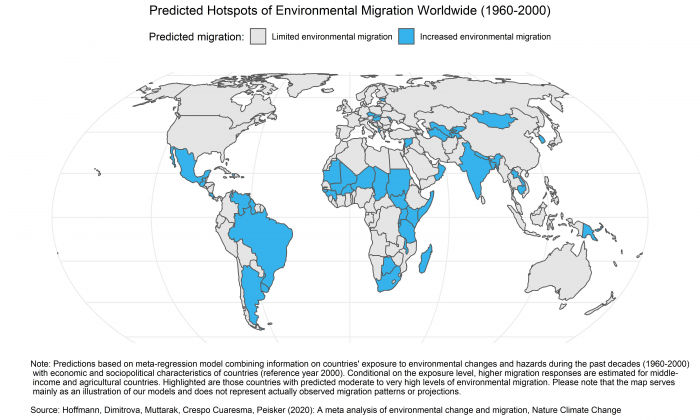

The migration-climate nexus is real, but more scrutiny and action are required

In 2018, the World Bank estimated that three regions (Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia) will generate 143 million more climate migrants by 2050. 3 In 2017, 68.5 million people were forcibly displaced, more than at any point in human history. While it is difficult to estimate, approximately one-third of these (22.5 million 4 to 24 million 5 people) were forced to move by “sudden onset” weather events—flooding, forest fires after droughts, and intensified storms. While the remaining two-thirds of displacements are the results of other humanitarian crises, it is becoming obvious that climate change is contributing to so-called slow onset events such as desertification, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, air pollution, rain pattern shifts and loss of biodiversity. 6 This deterioration will exacerbate many humanitarian crises and may lead to more people being on the move.

Multilateral institutions, development agencies, and international law must do far more to thoroughly examine the challenges of climate change (early efforts, like the World Bank’s 2010 World Development Report on climate change, 7 had little uptake at a time when few thought a climate crisis was around the corner). Moreover, neither a multilateral strategy nor a legal framework exist to account for climate change as a driver of migration. Whether in terms of limited access to clean water, food scarcity, agricultural degradation, or violent conflict, 8 climate change will intensify these challenges and be a significant push factor in human migration patterns.

To date, there are only a few cases where climate change is the sole factor prompting migration. The clearest examples are in the Pacific Islands. The sea level is rising at a rate of 12 millimeters per year in the western Pacific and has already submerged eight islands. Two more are on the brink of disappearing, prompting a wave of migration to larger countries. 9 10 By 2100, it is estimated that 48 islands overall will be lost to the rising ocean. 11 In 2015, the Teitota family applied for refugee status in New Zealand, fleeing the disappearing island nation of Kiribati. 12 Their case, the first request for refuge explicitly attributed climate change, made it to the High Court of New Zealand but was ultimately dismissed. Islands in the Federated States of Micronesia have drastically reduced in size, washed down to an uninhabitable state, had their fresh water contaminated by the inflow of seawater, and disappeared in the past decade. 13 Despite their extreme vulnerability, the relatively small population (2.3 million people spread across 11 countries 14 ) and remote location of the Pacific Islands means that they garner little international action, for all the attention they receive in the media.

Although there are few instances of climate change as the sole factor in migration, climate change is widely recognized as a contributing and exacerbating factor in migration and in conflict.

In South Asia, increasing temperatures, sea level rise, more frequent cyclones, flooding of river systems fed by melting glaciers, and other extreme weather events are exacerbating current internal and international migration patterns. Additionally, rapid economic growth and urbanization are accelerating and magnifying the impact and drivers of climate change—the demand for energy is expected to grow 66 percent by 2040. 15 Compounding this, many of the expanding urban areas are located in low-lying coastal areas, already threatened by sea level rise. 16 The confluence of these factors leads the World Bank to predict that the collective South Asian economy (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka) will lose 1.8 percent of its annual GDP due to climate change by 2050. 17 The New York Times reports that the living conditions of 800 million people could seriously diminish. 18 Diminishing living conditions on this scale and intensity will prompt mass migration—possibly at an unprecedented level.

Northwest Africa is facing rising sea levels, drought, and desertification. These conditions will only add to the already substantial number of seasonal migrants and put added strain on the country of origin, as well as on destination countries and the routes migrants travel. The destabilizing effects of climate change should be of great concern to all those who seek security and stability in the region. Climate and security experts often cite the impacts of the extreme drought in Syria that preceded the 2011 civil war. 19 The security community also highlights the connection between climate change and terrorism—for instance, the decline of agricultural and pastoral livelihoods has been linked to the effectiveness of financial recruiting strategies by al-Qaida. 20

The intersection of climate change and migration requires new, nimble, and comprehensive solutions to the multidimensional challenges it creates. Accordingly, the signatories to the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change requested that the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage Associated with Climate Change (WIM) develop recommendations for addressing people displaced by climate change. 21 Similarly, The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (adopted by 164 countries—not including the U.S.—in Marrakech in December 2018) called on countries to make plans to prevent the need for climate-caused relocation and support those forced to relocate. 22 However, these agreements are neither legally binding nor sufficiently developed to support climate migrants—particularly migrants from South Asia, Central America, Northwest Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

Time to envision legal recourse for climate refugees

As gradually worsening climate patterns and, even more so, severe weather events, prompt an increase in human mobility, people who choose to move will do so with little legal protection. The current system of international law is not equipped to protect climate migrants, as there are no legally binding agreements obliging countries to support climate migrants.

While climate migrants who flee unbearable conditions resemble refugees, the legal protections afforded to refugees do not extend to them. In the aftermath of World War II, the United Nations established a system to protect civilians who had been forced from their home countries by political violence. Today, there are almost 20.4 million officially designated refugees under the protection of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR)—however, there is an additional group of 21.5 million people 23 who flee their homes as a result of sudden onset weather hazards every year. 24

The UNHCR has thus far refused to grant these people refugee status, instead designating them as “environmental migrants,” in large part because it lacks the resources to address their needs. But with no organized effort to supervise the migrant population, these desperate individuals go where they can, not necessarily where they should. As their numbers grow, it will become increasingly difficult for the international community to ignore this challenge. As severe climate change displaces more people, the international community may be forced to either redefine “refugees” to include climate migrants or create a new legal category and accompanying institutional framework to protect climate migrants. However, opening that debate in the current political context would be fraught with difficulty. Currently, the nationalist, anti-immigrant, and xenophobic atmosphere in Europe and the U.S. would most likely lead to limiting refugee protections rather than expanding them.

The SDGs can help, but not without an update to the US response

While there are no legally binding international regimes that protect climate migrants, there are voluntary compacts that could be used to support them. Most notably, 193 countries adopted the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which address both migration and climate change.

Several of the 169 targets established by the SDGs lay out general goals that could be used to protect climate migrants. SDG 13 on climate action outlines several targets that address the climate crisis:

- 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries

- 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning

- 13.3: Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction, and early warning.

To meet these goals, extensive bilateral and multilateral development assistance will be needed. The U.S. must create a strategic approach to focus development assistance and multilateral organizations on those targets—particularly to create resilient societies that can keep people in their communities.

Although the SDGs do not explicitly link climate change and migration, SDG target 10.7 calls for signatories to “facilitate orderly, safe, and responsible migration of people, including through implementation of planned and well-managed policies.” Again, the United States should channel multilateral development assistance to support the implementation of this target.

The scale and scope of climate change demand dynamic and comprehensive solutions. The U.S. must address climate stress on vulnerable populations specifically, rather than funneling more money into existing programs that operate on the periphery of the growing crisis.

U.S. development agencies and international development financial institutions need to redirect their development assistance to incorporate today’s unfolding climate crisis. Significantly more resources will need to be channeled to the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (USDFC), USAID, the Green Climate Fund, UNHCR, as well as to other critical international bodies, in particular those that make up the International Red Cross and Red Crescent organizations.

The Obama administration undertook myriad efforts to update the institutions that can address climate. Several of President Obama’s executive orders, particularly Executive Order 13677, which required incorporating climate resilience into decisionmaking on development assistance, took on the climate crisis. For the first time in the Department of Defense’s history, the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) recognized climate change as a “threat multiplier,” with the potential to exacerbate current challenges. 25

While the current administration has deemphasized or opposed climate-friendly approaches, the current security implications of the migration crisis might prompt a re-examination of those policies. There should be bipartisan support, particularly in the security community, for reducing the conditions that accelerate international migration.

The case for scaling up US action to confront the climate crisis

A variety of medium-term investments (five to 10 years) could create more resilience to the effects of climate change. For example, the climate change factors that push migration in Northwest Africa could—at least in part—be addressed by supporting irrigation infrastructure, providing food supplies, fostering regional water cooperation, and supporting livelihood security. 26

Dedicating greater resources to mitigate climate migration is also part of an effective solution. Research is needed to determine the best way to improve the migratory process itself—be it increasing migration monitors, providing safer modes of transport, and consolidating and expanding destination country integration resources.

This discussion is not new: In 2010, Center for American Progress staff were part of a task force that suggested a “Unified Security Budget” for the United States, to address complex crisis scenarios that transcend the traditional division of labor among defense, diplomacy, and development. 27 The need for longer-term, more calculated assessment strategies and investments has only increased over the past decade. The Pentagon already supports a variety of operational missions that respond to sudden onset climate disasters. The Navy, in particular, serves at the emergency hotline for international extreme weather events and mobilized to support the Haitian people after the 2010 earthquake, the Filipino people after the 2013 typhoon, and the Nepalis after the 2015 earthquake.

Alternatively, creating a single dedicated fund (by drawing funds from Operations and Maintenance, Research and Development, and the Refugee Assistance Fund) would allow the United States to streamline and refine its support strategies, address the effects of climate change directly, and rebuild its reputation abroad. Such a dedicated fund should try to emulate and partner with the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), Germany’s Society for International Cooperation (GIZ), and Japan’s International Cooperation Agency (JICA). American seed funding in this area could lead to major investments of allies and partners—and in cooperation with the development agencies of these countries can mobilize massive resources at the scale required to confront the global climate crisis.

The strategies to address climate migrants presented here are far reaching, but this crisis will only intensify, and our response to it will define international relations in the 21st century.

Related Content

Walter Kälin

July 16, 2008

October 10, 2008

Reva Dhingra, Elizabeth Ferris

November 1, 2022

Related Books

Simon J. Evenett, Alexander Lehmann, Benn Steil

October 1, 2000

Ted Piccone

February 23, 2016

Richard Klingler

June 1, 1996

- United Nations. “UNHCR Factsheet: Cyclone Idai.” May 2019.

- Reid, Kathryn “2019 Cyclone Idai.” World Vision. April 26. 2019. https://www.worldvision.org/disaster-relief-news-stories/2019-cyclone-idai-facts

- Kumari Rigaud, Kanta, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Jonas Bergmann, Viviane Clement, Kayly Ober, Jacob Schewe, Susana Adamo, Brent McCusker, Silke Heuser, and Amelia Midgley. 2018. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. The World Bank. Pg 2. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29461

- McDonnell, Tim. “The Refugees the World Barely Pays Attention To.” June 20, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/06/20/621782275/the-refugees-that-the-world-barely-pays-attention-to.

- The Nansen Initiative. “Disaster-Induced Cross-Border Displacement.” December 2015. Page 6. https://nanseninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PROTECTION-AGENDA-VOLUME-1.pdf

- “Slow Onset Events.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/constituted-bodies/executive-committee-of-the-warsaw-international-mechanism-for-loss-and-damage-wim-excom/areas-of-work/slow-onset-events

- “World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change.” World Bank. 2010. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/4387

- “How Climate Change Can Fuel Wars.” The Economist. May 23, 2019. https://www.economist.com/international/2019/05/25/how-climate-change-can-fuel-wars

- Nunn, P.D., Kohler, A. & Kumar, R. “Identifying and Assessing Evidence for Recent Shoreline Change Attributable To Uncommonly Rapid Sea-Level Rise in Pohnpei, Federated State of Micronesia, Northwest Pacific Ocean.” Journal of Coast Conservation (2017) 21: 719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-017-0531-7

- Roy, Eleanor Ainge, and Sean Gallagher. “One day we’ll Disappear: Tuvalu’s Sinking Islands” The Guardian. May 16, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/may/16/one-day-disappear-tuvalu-sinking-islands-rising-seas-climate-change

- Deshmukh, Amrita. “Disappearing Island Nations Are The Sinking Reality of Climate Change.” Qrius. May 17, 2019. https://qrius.com/disappearing-island-nations-are-the-sinking-reality-of-climate-change/

- “New Zealand: Climate Change Refugee Case Overview.” Law Library of Congress. July 29, 2015. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/climate-change-refugee/new-zealand.php

- Nunn, Patrick D., Augustine Kohler, and Roselyn Kumar. “Identifying and Assessing Evidence For Recent Shoreline Change Attributable To Uncommonly Rapid Sea-Level Rise in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia, Northwest Pacific Ocean.” SpringerLink, July 13, 2017. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11852-017-0531-7

- “The World Bank in Pacific Islands.” World Bank. April 8, 2019. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pacificislands/overview

- Prakash, Amit. “Boiling Point.” Finance and Development, September 2018, Vol. 55. No. 3. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2018/09/southeast-asia-climate-change-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions-prakash.htm

- Nansen Initiative Secretariat. “Climate Change, Disasters, and Human Mobility is South Asia and Indian Ocean: Background Paper.” April 5, 2015. Pg 11.

- “Climate Change Danger to South Asia’s Economy.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. August 19, 2014. https://unfccc.int/news/climate-change-danger-to-south-asias-economy

- Sengupta, Somini, and Nadja Popovich. “Global Warming in South Asia: 800 Million at Risk.” The New York Times. June 28, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/28/climate/india-pakistan-warming-hotspots.html

- Gleick, Peter. “Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria.” Pacific Institute of Oakland California. July 1, 2014. https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

- Werz, Michael, and Laura Conley. “Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict in Northwest Africa.” Center for American Progress. April 2012. Pg 8.

- United Nations Human Rights Council. “The Slow Onset Effects of Climate Change and Human Rights Protection for Cross-Border Migrants.” March 23, 2018. Pg 10.

- Specifically, articles 18.H (share information to better map and predict migration based on climate change and environmental degradation), 18.I (develop adaptation and resilience strategies that prioritize the country of origin), 18.J (factor in human displacement in disaster preparedness strategies), and 18.K (support climate-displaced persons at the sub-regional and regional levels). United Nations. “Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration: Intergovernmentally Negotiated and Agreed Outcomes. July 13, 2018. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/180713_agreed_outcome_global_compact_for_migration.pdf

- United Nations. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018.” June 20, 2019 UNHCR. www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html

- United Nations. “Frequently asked questions on climate change and disaster displacement.” November 6, 2016. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/latest/2016/11/581f52dc4/frequently-asked-questions-climate-change-disaster-displacement.html

- Department of Defense. “Quadrennial Defense Review Report” February 2010. Pages 84-89. https://history.defense.gov/Portals/70/Documents/quadrennial/QDR2010.pdf?ver=2014-08-24-144223-573

- Werz, Michael, and Laura Conley. “Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict in Northwest Africa.” Center for American Progress. April 2012. Pg 3.

- Pemberton, Miriam, and Lawrence Korb. “Report of the Task Force on A Unified security Budget for the United States.” Institute for Policy Studies. August 2010. https://fpif.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/USB_FY2011.pdf

Migrants, Refugees & Internally Displaced Persons U.S. Foreign Policy

Global Economy and Development

Cheng Li, Xiuye Zhao

June 14, 2023

Pavel K. Baev, Jessica Brandt, Daniel S. Hamilton, Patricia M. Kim, Adam P. Liff, Natalie Sambhi, David G. Victor

May 19, 2023

Online Only

10:00 am - 11:15 am EDT

- DOI: 10.1080/23251042.2019.1613030

- Corpus ID: 189673196

Environmental migration and displacement: a new theoretical framework for the study of migration aspirations in response to environmental changes

- L. Van Praag , C. Timmerman

- Published in Environmental Sociology 6 May 2019

- Environmental Science, Sociology

27 Citations

Applying insights of theories of migration to the study of environmental migration aspirations.

- Highly Influenced

Navigating tomorrow’s horizons: exploring the interplay of environmental factors in mobility decision-making among migrants in the Lowlands

How environmental change relates to the development of adaptation strategies and migration aspirations, appraising the role of the environment as a shaping element of migrants’ fragmented journeys, natural resources, human mobility and sustainability: a review and research gap analysis, a qualitative study of the migration-adaptation nexus to deal with environmental change in tinghir and tangier (morocco), gender, environmental change, and migration aspirations and abilities in tangier and tinghir, morocco, a qualitative study on how perceptions of environmental changes are linked to migration in morocco, senegal, and dr congo.

- 10 Excerpts

Adaptive Governance to Manage Human Mobility and Natural Resource Stress

Post-disaster (im)mobility aspiration and capability formation: case study of southern california wildfire, 69 references, environmental migration and social inequality, placing the environment in migration: environment, economy, and power in ghana's central region, the role of human agency in environmental change and mobility: a case study of environmental migration in southeast philippines, migration transitions: a theoretical and empirical inquiry into the developmental drivers of international migration, migration aspirations and migration cultures: a case study of ukrainian migration towards the european union, migration theory: quo vadis, the relevance of a “culture of migration” in understanding migration aspirations in contemporary turkey, how can migration support adaptation different options to test the migration – adaptation nexus, the internal dynamics of migration processes: a theoretical inquiry, stranded migrants and the fragmented journey.

- Highly Influential

Related Papers

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 26 November 2019

From migration to mobility

Nature Climate Change volume 9 , page 895 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

4300 Accesses

7 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

By many accounts, climate change is already driving human migration, but fresh thinking about the consequences of increasingly stringent borders, the intervening effects of global and local policy and how best to characterize human adaptive responses is needed to properly understand whether a crisis is on the horizon.

There is no question that climate change will impact human migration. The potential triggers are many: sea-level change leading to coastal flooding, drought destroying agricultural livelihoods, extreme heat threatening human health. By 2050, estimates for the expected number of environmental migrants are between 25 million and 1 billion. These numbers are, of course, uncertain and debated. But the idea of masses teeming from storm-ravaged and drought-stricken land is probably wrong, or at most only one small aspect of what is likely to unfold. When, where and how people will be forced to move as a consequence of climate change remains elusive, as are definitions about what it means to be a climate migrant and how best to govern the problem. In this issue and an accompanying online collection ( www.nature.com/collections/climate-migration ), we explore many of these questions and what needs to be done to improve our understanding of the complex, multi-faceted interaction between climate change and human migration.

Everything from livelihoods to identity is affected by the environments in which we live, so it makes sense that environmental change would influence decisions to stay or go. Although not always explicit, classic migration theory is generally compatible with the idea that environmental factors matter, and there is a rapidly growing literature contributing to migration–environment theory. There are a few things we know at this point: (1) migration is a fundamental strategy for addressing household risk arising from the environment; (2) environmental factors interact with broader sociopolitical histories; and (3) the migration–environment association is shaped by social networks (L. M. Hunter et al., Annu. Rev. Sociol . 41 , 377–397; 2015).

Notably, what we know about environmental migration is that a lot of non-environmental factors matter. An improved understanding of the physical processes alone is important, but as Wrathall et al. explain in this issue , exposure to sea-level change is driven concurrently by global policy decisions determining future greenhouse gas emissions and local policies at the migrants’ point of origin. To get a better handle on the space of potential outcomes, they advocate for improved modelling that prioritizes scenarios consistent with global objectives (the Paris Agreement goals), allows for consideration of local and national policies, and focuses first on predicting migration through 2050.

Migration decisions are further impacted by policies at potential destinations. Although exposure to climate risks is sure to be broad, whether climate change leads to a larger number of migrants is at least in part conditional on whether those at risk have somewhere to go. In a Perspective in this issue, Robert McLeman discusses how restrictive policies, criminalization of asylum seekers and securitization of immigration is increasingly closing the door to international migration. With nowhere to go, the vulnerable may be forced to stay put and forgo using migration as an adaptation strategy.

For example, in a News & Views article in this issue, Cristina Cattaneo explores a recent study looking at the role of migrant networks in shaping disaster-induced migration to the United States. This new research shows that prior migrants amplify international migration flows in the aftermath of hurricanes. Although the results are consistent with migration being used as an adaptive strategy, they also suggest that migration may not be a pathway available to those who need it the most. For reasons such as this, McLeman advocates for more explicit application of the United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration ( A/RES/73/195, 2018 ) to facilitate international migration in response to climate hazards.

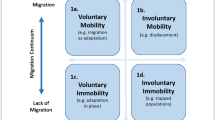

Perhaps our inability to wrap our heads around the problem at the policy level arises because we have completely mischaracterized the problem that needs to be solved. In a Comment in this issue, Ingrid Boas and colleagues argue that framing climate migration as an impending security risk for the developed world hinders efforts to advance knowledge and policy that properly account for the complex nature of the problem. They argue for a reorientation of research and funding to focus on the full range of mobilities likely to result from climate change.

Environmental migration occurs both between and within countries; it may be temporary or permanent; it may follow existing routes or forge new ones. The ultimate challenge is to find solutions to reduce the climate risks that lie ahead. The need to rethink migration in terms of mobilities is pressing, especially in light of the difficulties in establishing a super-framework for climate migration. For many, the question is not whether or when they will be impacted, but how they should retreat now, and what are the costs of doing so. A News Feature in this issue highlights these very challenges for Newtok, Alaska and Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana in the United States, both of which are in search of ways to relocate their threatened coastline communities away from the sea. Retreat may be inevitable. And, although this is unlikely to include refugees on foot crossing international borders, these residents are very much climate migrants. It is for this reason that new models, new conceptions or new policies are needed to understand the full space of human responses to climate change.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

From migration to mobility. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9 , 895 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0657-8

Download citation

Published : 26 November 2019

Issue Date : December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0657-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Biodiversity

- Cities & society

- Land & water

- All research news

- All research topics

- Learning experiences

- Programs & partnerships

- All school news

- All school news topics

- In the media

- For journalists

How does climate change affect migration?

April 2021 saw a 20-year high in the number of people stopped at the U.S./Mexico border, and President Joe Biden recently raised the cap on annual refugee admissions. Stanford researchers discuss how climate change’s effect on migration will change, how we can prepare for the impacts and what kind of policies could help alleviate the issue.

In the face of a mounting humanitarian crisis at the U.S./Mexico border, the Biden administration has acknowledged climate change among the powerful forces pushing migrants from Central America. A $4 billion federal commitment to address the root causes of irregular migration acknowledges the need for adaptation efforts to help alleviate the situation.

The challenge is not limited to the border. Last year, weather-related disasters around the world uprooted 30 million people – more than the population of the 14 largest U.S. cities combined – and wildfires displaced more than a million Americans, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

Below, Stanford climate and behavior experts discuss how climate change’s effect on migration will change, how we can prepare for the impacts and what kind of policies could help alleviate the issue. The researchers include Chris Field , a climate scientist who has led UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change efforts to analyze climate-related risks, impacts and adaptation opportunities; Gabrielle Wong-Parodi , a behavioral scientist who studies how people react to challenges associated with global environmental change; Erica Bower , a PhD student who studies human mobility in the context of climate change impacts and served as a climate change and disaster displacement specialist at the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees; Nina Berlin Rubin , a PhD student in Earth system science whose research focuses on decision-making in the face of climate extremes.

What is a common story of climate migration in the U.S./Mexico?

Bower : Climate change is a threat multiplier – it can exacerbate economic insecurity or political instability, which in turn may lead to migration. In the “dry corridor” of Central America, for example, climate change extremes such as droughts may hinder crop production. Without a consistent source of food or income, a farmer may seek other livelihood opportunities in a nearby city or further north. When combined with poverty or violence, a drought may make the perilous journey north seem to be a more promising adaptation or survival strategy.

How has climate change’s effect on the tide of refugees in the U.S./Mexico border changed in recent years?

Bower : In recent years, climate change has made extreme weather events stronger and more frequent, which may contribute to migration decisions. However, given the multiple reasons why people move, we do not have the evidence required to say with certainty precisely how climate change has affected net migration flows to the U.S./Mexico border.

What does the future hold for climate-related migration at the border? What should we expect, and how should we prepare for it?

Field : In the long run, stopping climate change is a key element of getting the situation under control. In the short run, there are lots of effective ways to decrease vulnerability. These range from improving agricultural practices to strengthening social safety nets. Across the full suite of possible vulnerability reduction measures, it is critical that the solutions are implemented in partnership with local communities and not imposed on them. In regions with high levels of corruption or political or criminal violence, it is much more challenging to make progress on vulnerability reduction.

Bower : We may need to change our approach to welcoming people across our southern border. The definition of refugee in international law is very narrow, and most people fleeing in climate change contexts – including from Central America to the U.S./Mexico border – are generally not recognized as refugees under international or domestic law. Newly proposed legislation in Congress would protect the human rights of people fleeing to the U.S. in the context of climate change.

Leaving is only half the story. Tracking these migration pathways from origin to destination can speak to whether people are moving to safer areas or to areas that introduce new or heightened risks. ” Nina Berlin Rubin PhD student, Department of Earth System Science

How extensive is climate change’s effect on migration within the U.S.?

Wong-Parodi : We are seeing some evidence that people who feel more impacted by wildfires and secondary impacts like smoke are more likely to intend to move to a new state within the U.S. or even out of the country. The question that remains is whether the destination they are planning on moving to is more or less at risk for wildfires or other climate hazards.

Berlin Rubin : Exactly. One might decide to uproot their family and leave behind friends and neighbors in search of respite from wildfires and smoke, only to find themselves living somewhere with just as much wildfire risk – or exposure to other risks like flooding – as where they were before. And the reality is, as these fires become more frequent and destructive, people will have fewer options and less confidence that their destination is actually going to be free from wildfires.

Bower : We are also seeing that many communities are seeking government support to relocate away from sea level rise or flooding. A recent mapping exercise identified 36 cases of community-wide relocation in the U.S. alone since 1970.

How might federal and state policy lessen climate change’s impact role as a driver of migration at the border and within the U.S.?

Field : The U.S. Federal government can play a large role in addressing the core drivers of displacement, through three main pathways. It can decrease its contribution to warming through decreasing its greenhouse gas emissions. It can help other countries decrease their emissions through financial and technical assistance. It can also help poor countries adapt so that their people feel less pressure to migrate. This last pathway has the potential to be especially cost-effective in the near term, even though it cannot address all of the drivers of migration.

Is there any promising research/data gathering that could dramatically change how we understand and react to this challenge?

Field : It is likely that progress in decreasing pressure to migrate will require patience. One area where data can make a big difference is in cataloging investments in adaptation and following their consequences. At this point, we are not systematically cataloging and tracking adaptation efforts. A robust database can be the foundation for a new generation of evidence-based adaptation.

Berlin Rubin : Research at the individual level will help us better understand and characterize the psychosocial and experiential factors that motivate climate-related migration decisions. But leaving is only half the story. Tracking these migration pathways from origin to destination can speak to whether people are moving to safer areas or to areas that introduce new or heightened risks. We need to understand the local context in which people are making their decisions in order to get ahead of these challenges.

Field is the Perry L. McCarty Director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment , the Melvin and Joan Lane Professor for Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies, a professor of Earth system science and biology and a senior fellow at the Precourt Institute for Energy . Wong-Parodi is an assistant professor of Earth system science in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences ; and a center fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment . Bower is a PhD student in the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

Related research

How does climate change affect disease.

As the globe warms, mosquitoes will roam beyond their current habitats, shifting the burden of diseases like malaria, dengue fever, chikungunya and West Nile virus. Researchers forecast different scenarios depending on the extent of climate change.

The effects of climate change on water shortages

In Jordan, one of the most water-poor nations, predictions of future droughts depend on the scale of climate change. Without reducing greenhouse gases the future looks dry, but researchers offer some hope.

Media Contacts

Chris Field Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment (650) 823-5326; [email protected]

Gabrielle Wong-Parodi School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (650) 725-6457; [email protected]

Erica Bower School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (203) 666-9892; [email protected]

Nina Berlin Rubin School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (307) 690-4234; [email protected]

Rob Jordan Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment (650) 721-1881; [email protected]

Explore More

How much does air pollution cost the U.S.?

Damages from air pollution have fallen dramatically in the U.S. in recent years, shows new research. But how different sectors of the economy have contributed to that decline is highly uneven.

Students learn new skills with scientist-in-training programs

Jennifer Saltzman discussed her role in the Bright STaRS program, which has been influential for scholars at Stanford Earth including Farm intern Claire Valva, local high schooler Michael Wucher and alumni Daniel Ibarra and Jason Stuckey.

- School news

Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels reached record high in 2023

Declining coal use helped shrink U.S. emissions 3%, according to new estimates from the Global Carbon Project, even as global emissions keep the world on a path to exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming before 2030 and 1.7 degrees soon after.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 6 Environmental Migration∗

- Published: January 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Environmental migration is not a new phenomenon. Natural and human-induced environmental disasters have displaced people in the past and continue to do so. Nevertheless, the environmental events and processes accompanying global climate change threaten to dramatically increase human movement both within and across State borders. Estimates suggest that between 200 and 250 million people will be displaced by environmental causes before 2050. The environmental impacts of climate change have been signalled as the key driver of this anticipated surge in migration.Evidently, migration on this unprecedented scale demands a multilateral institutional response. Yet, environmental migration governance represents a significant challenge, not least because the content and parameters of the concept continue to be debated. There is at present no internationally agreed definition of what it means to be an environmental ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, or ‘displaced person’, and, consequently, no agreed label for those affected. Questions of definition have clear governance implications, informing the appropriate location of environmental migration both procedurally—as an international, regional, or local, developed and/or developing country concern/responsibility—and thematically—for example, within the existing refugee protection framework or under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The viability and value of institutionalizing international cooperation and collaboration on international migration matters generally, and environmental migration particularly, depends upon how that phenomenon can and should be formulated as a discrete concept in law and policy. Taking a legal perspective, this chapter grounds its normative analysis in a thorough examination and assessment of the existing institutions and political processes that impact upon environmental migration and States' responses to them.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 11 |

| November 2022 | 15 |

| December 2022 | 15 |

| January 2023 | 10 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 15 |

| April 2023 | 11 |

| May 2023 | 15 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 4 |

| September 2023 | 6 |

| October 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| December 2023 | 6 |

| January 2024 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 11 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 8 |

| May 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

A systematic review of climate migration research: gaps in existing literature

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 47 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rajan Chandra Ghosh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9027-6649 1 , 2 &

- Caroline Orchiston ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-2006 1

13k Accesses

20 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

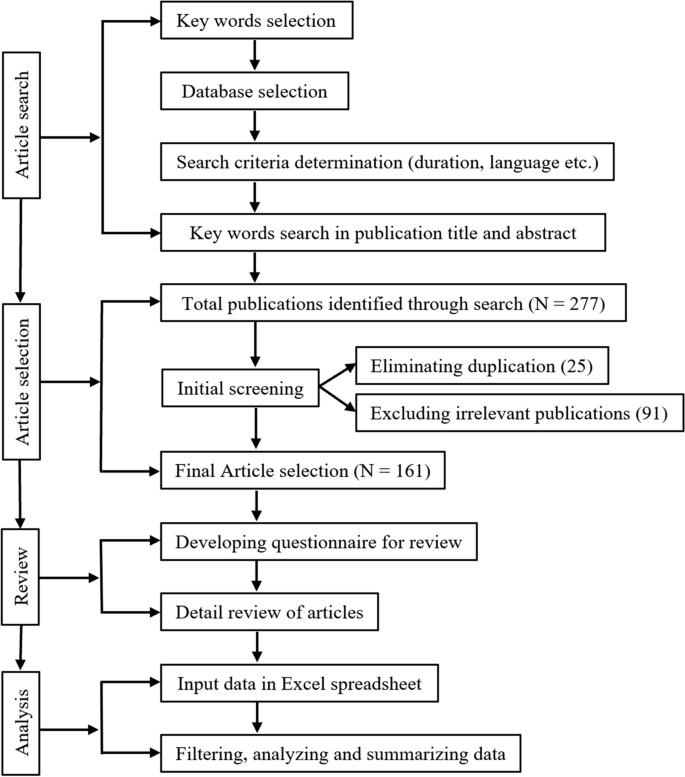

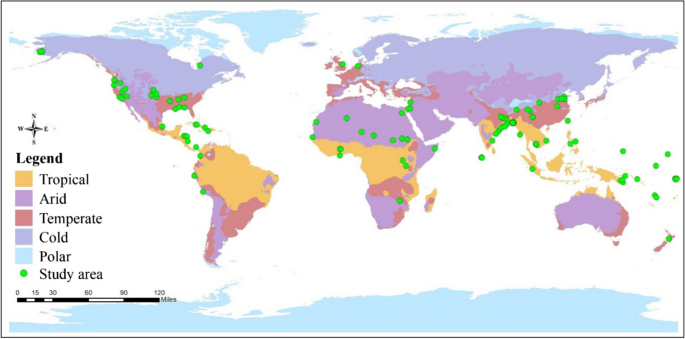

Climatic disasters are displacing millions of people every year across the world. Growing academic attention in recent decades has addressed different dimensions of the nexus between climatic events and human migration. Based on a systematic review approach, this study investigates how climate-induced migration studies are framed in the published literature and identifies key gaps in existing studies. 161 journal articles were systematically selected and reviewed (published between 1990 and 2019). Result shows diverse academic discourses on policies, climate vulnerabilities, adaptation, resilience, conflict, security, and environmental issues across a range of disciplines. It identifies Asia as the most studied area followed by Oceania, illustrating that the greatest focus of research to date has been tropical and subtropical climatic regions. Moreover, this study identifies the impact of climate-induced migration on livelihoods, socio-economic conditions, culture, security, and health of climate-induced migrants. Specifically, this review demonstrates that very little is known about the livelihood outcomes of climate migrants in their international destination and their impacts on host communities. The study offers a research agenda to guide academic endeavors toward addressing current gaps in knowledge, including a pressing need for global and national policies to address climate migration as a significant global challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate-Conflict-Migration Nexus: An Assessment of Research Trends Based on a Bibliometric Analysis

Scales and sensitivities in climate vulnerability, displacement, and health

Climate change-induced migration: a bibliometric review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population displacement can be driven by climatic hazards such as floods, droughts (hydrologic), and storms (atmospheric), and geophysical hazards such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunami (Smith and Smith 2013 ). The interactions between natural hazard events, and social, political, and human factors, frequently act to intensify the negative effects of climatic and geophysical hazards, leading to political and social unrest, increased social vulnerability, and human suffering. As a consequence of these adverse effects, people migrate from their native land, causing stress, uncertainty, and loss of lives and properties. However, such migration can also have positive impacts on migrants’ lives. For example, migrants may be able to diversify their livelihood and have greater access to education or healthcare.

In 2020, 30.7 million people from 149 countries and territories were displaced due to different natural disasters. Among them, climatic disasters were solely responsible for displacing 30 million people within their own country, with the highest recorded displacement occurring in 2010 when 38.3 million people were displaced (IDMC 2021a ; IOM 2021 ). It is difficult to estimate the actual number of people that moved due to the impacts of climate change (Mcleman 2019 ), because peoples’ migration decisions are triggered by a range of contextual factors (de Haas 2021 ). Nevertheless, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) states that approximately 283.4 million people were displaced internally between the years 2008 and 2020 because of climatic disasters across the globe (Table 1 ). This number represents almost 89% of the total disaster-induced displacement that occurred during this timeframe (IDMC 2021a ).

People who move from their homes due to climate-driven hazards are described in a range of ways, including climate migrants, environmental migrants, climate refugees, environmental refugees, and so on (Perkiss and Moerman 2018 ). The process of migration related to climate-driven hazards is variously described as environmental migration, environmental displacement, climate-induced migration or climigration (Bronen 2008 ).

In this research, we focus on climate-induced migration more specifically induced by slow-onset climatic disasters (sea-level rise, drought, salinity etc.), rapid onset extreme climatic events (storms, floods etc.), or both (precipitation, erosion etc.). This study investigates how climate change-induced migration studies are framed in the existing literature and identifies key gaps in the published literature.

There is a significant ongoing debate about the links between climate change and human migration in the academic literature. Some researchers strongly believe that climate change directly causes people to move, whereas the others argue that climate change is just one of the contextual factors in peoples’ migration decisions (Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ). Although there are scholarly opinions that call into question climate change as a primary cause of migration (Black 2001 ; Black et al. 2011 ; McLeman 2014 ), there is also evidence that climate change causes severe environmental effects and exacerbates the vulnerabilities of people that force them to leave their place of living (Bronen and Chapin 2013 ; Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ; McLeman 2014 ).