- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

The Rhetoric That Shaped The Abortion Debate

Women take part in a 1977 demonstration in New York City demanding safe and legal abortions for all women. Peter Keegan/Stringer/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

Women take part in a 1977 demonstration in New York City demanding safe and legal abortions for all women.

Before Roe v. Wade: Voices that Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court's Ruling By Linda Greenhouse and Reva B. Siegel Hardcover, 352 pages Kaplan Publishing List Price: $26

Before the Supreme Court struck down many state laws restricting abortion in the 1973 landmark case Roe v. Wade , the Justices read briefs from both abortion-rights supporters and opponents.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Linda Greenhouse has collected the best of these briefs -- as well as important documents leading up to the decision -- in a new book, Before Roe v. Wade: Voices that Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court's Ruling.

In an interview on Fresh Air, Greenhouse explains the arguments in favor of decriminalizing abortion -- and the rhetoric used by both sides of the debate that continues to resonate more than 35 years after Roe.

After researching the book, Greenhouse says, she came away with a more nuanced understanding of how the abortion debate has affected so many other issues.

"What the research did indicate to me is how multifaceted the issue is and how the word [abortion] came over time to stand for so much more than the termination of a pregnancy," she says. "It really came to stand for a debate about the place of women in the world."

Linda Greenhouse is a senior fellow at Yale Law School. She covered the Supreme Court for The New York Times for three decades. courtesy of the author hide caption

Linda Greenhouse is a senior fellow at Yale Law School. She covered the Supreme Court for The New York Times for three decades.

Interview Highlights

On why the medical community's lobbying groups shifted to support the decriminalization of abortion

"The medical impetus to start reforming the old abortion laws actually came, not from the American Medical Association but from the American Public Health Association -- from the public health profession. There is a public health doctor, Mary Calderon, who was medical director of Planned Parenthood and also very active in professional public health circles. She wrote some influential articles depicting abortion as a serious public health issue -- that is to say, illegal abortion, back-alley abortion, as a serious public health issue -- and basically started calling on the medical profession to take a new look at this old issue. Abortion could now be a very safe medical procedure when done properly and under the right conditions. And so the facts on the ground had changed: Women were having secret abortions in large numbers; there was a good deal of medical bad consequences and suffering because of this, and it was really the public health doctors who sounded the call."

On the use of the phrase 'the right to choose'

"Jimmye Kimmey was a young woman who was executive director of an organization called the Association for the Study of Abortion (ASA), which was one of the early reform groups and was migrating in the early 1970s from a position of reforming the existing abortion laws to the outright repeal of existing abortion laws, and she wrote a memorandum framing the issue of how the pro-repeal position should be described: 'Right to life is short, catchy, composed of monosyllabic words -- an important consideration in English. We need something comparable. Right to choose would seem to do the job. And ... choice has to do with action, and it's action that we're concerned with.' "

On the significance of J.C. Willke, who wrote Handbook on Abortion

"He is a key figure in the right-to-life movement. He and his wife self-published this little book called Handbook on Abortion in 1971 in the form of questions and answers about abortions from the right-to-life point of view. And it got distributed like wildfire. It now exists in many, many editions. People can go on Google and Amazon and find it easily. It's been translated in many languages, and it really became a Bible of the right-to-life movement. And we were grateful to Dr. Willke for giving us permission to republish it. The reason we wanted to have a substantial excerpt from it is because people on the pro-choice side, I'm quite certain, have never seen it. And it's a very striking document and his voice was and continues to be an important voice on that side."

On feminism's role in shaping the abortion debate

"The feminist community at that time, in the mid-'60s, was much more interested in empowering women to take a full place in the economy, in the world-place. Things like child care. Things like equal pay. Things like getting rid of sex-specific help-wanted ads. Woman wanted, man wanted -- that type of thing. And there wasn't much talk about abortion reform in feminist circles until quite late in the '60s, when Betty Friedan, in a very influential speech, drew the connection between the ability of women to participate fully in the economy and the ability of women to control their reproductive lives. That began a reframing in feminist terms of the issue of abortion reform as part of women's empowerment and of women assuming a new role in society."

Related NPR Stories

Linda greenhouse, looking closely at the supreme court, 'becoming justice blackmun' by greenhouse.

Before Roe v. Wade

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Excerpt: 'Before Roe v. Wade'

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, supreme court case, roe v. wade (1973).

410 U.S. 113 (1973)

“We . . . conclude that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.”

Selected by

Caroline Fredrickson

Visiting Professor, Georgetown University Law Center and Senior Fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice

Ilan Wurman

Associate Professor, Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University

At a time when Texas law restricted abortions except to save the life of the mother, Jane Roe (a single, pregnant woman) sued Henry Wade, the local district attorney tasked with enforcing the abortion statute. She argued that the Texas law was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court agreed, holding that the right of privacy, inherent in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, protects a woman’s choice to have an abortion. That right is limited, however, as the pregnancy advances, by the State’s interest in maternal health and in fetal life after viability. Amid national debate over this issue, this was the first time the Court took up this question and affirmed the “right to choose,” as it is often titled.

Read the Full Opinion

Excerpt: Majority Opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun

The Constitution does not explicitly mention any right of privacy. In a line of decisions, however, . . . the Court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy, does exist under the Constitution. In varying contexts, the Court or individual Justices have, indeed, found at least the roots of that right in the First Amendment; in the Fourth and Fifth Amendments; in the penumbras of the Bill of Rights; in the Ninth Amendment; or in the concept of liberty guaranteed by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment. These decisions make it clear that only personal rights that can be deemed ‘fundamental’ or ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,’ are included in this guarantee of personal privacy. They also make it clear that the right has some extension to activities relating to marriage; procreation; contraception; family relationships; and child rearing and education.

This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy. The detriment that the State would impose upon the pregnant woman by denying this choice altogether is apparent. Specific and direct harm medically diagnosable even in early pregnancy may be involved. Maternity, or additional offspring, may force upon the woman a distressful life and future. Psychological harm may be imminent. Mental and physical health may be taxed by child care. There is also the distress, for all concerned, associated with the unwanted child, and there is the problem of bringing a child into a family already unable, psychologically and otherwise, to care for it. In other cases, as in this one, the additional difficulties and continuing stigma of unwed motherhood may be involved. All these are factors the woman and her responsible physician necessarily will consider in consultation. . . .

The Court’s decisions recognizing a right of privacy also acknowledge that some state regulation in areas protected by that right is appropriate. [A] State may properly assert important interests in safeguarding health, in maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life. At some point in pregnancy, these respective interests become sufficiently compelling to sustain regulation of the factors that govern the abortion decision. The privacy right involved, therefore, cannot be said to be absolute. In fact, it is not clear to us that the claim . . . that one has an unlimited right to do with one’s body as one pleases bears a close relationship to the right of privacy previously articulated in the Court’s decisions. The Court has refused to recognize an unlimited right of this kind in the past.

We, therefore, conclude that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.

To summarize and to repeat:

1. A state criminal abortion statute of the current Texas type, that excepts from criminality only a lifesaving procedure on behalf of the mother, without regard to pregnancy stage and without recognition of the other interests involved, is violative of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman’s attending physician.

(b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health.

(c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother. . . .

This holding, we feel, is consistent with the relative weights of the respective interests involved, with the lessons and examples of medical and legal history, with the lenity of the common law, and with the demands of the profound problems of the present day. The decision leaves the State free to place increasing restrictions on abortion as the period of pregnancy lengthens, so long as those restrictions are tailored to the recognized state interests. The decision vindicates the right of the physician to administer medical treatment according to his professional judgment up to the points where important state interests provide compelling justifications for intervention. Up to those points, the abortion decision in all its aspects is inherently, and primarily, a medical decision, and basic responsibility for it must rest with the physician. . . .

Excerpt: Dissent, Justice William Rehnquist

The Court’s opinion brings to the decision of this troubling question both extensive historical fact and a wealth of legal scholarship. While the opinion thus commands my respect, I find myself nonetheless in fundamental disagreement with those parts of it that invalidate the Texas statute in question, and therefore dissent. . . .

I have difficulty in concluding, as the Court does, that the right of “privacy” is involved in this case. Texas, by the statute here challenged, bars the performance of a medical abortion by a licensed physician on a plaintiff such as Roe. A transaction resulting in an operation such as this is not ‘private’ in the ordinary usage of that word. Nor is the ‘privacy’ that the Court finds here even a distant relative of the freedom from searches and seizures protected by the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, which the Court has referred to as embodying a right to privacy.

If the Court means by the term “privacy” no more than that the claim of a person to be free from unwanted state regulation of consensual transactions may be a form of “liberty” protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, there is no doubt that similar claims have been upheld in our earlier decisions on the basis of that liberty. I agree with the statement of MR. JUSTICE STEWART in his concurring opinion that the “liberty,” against deprivation of which without due process the Fourteenth Amendment protects, embraces more than the rights found in the Bill of Rights. But that liberty is not guaranteed absolutely against deprivation, only against deprivation without due process of law. The test traditionally applied in the area of social and economic legislation is whether or not a law such as that challenged has a rational relation to a valid state objective. . . . The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment undoubtedly does place a limit, albeit a broad one, on legislative power to enact laws such as this. If the Texas statute were to prohibit an abortion even where the mother’s life is in jeopardy, I have little doubt that such a statute would lack a rational relation to a valid state objective . . . . But the Court’s sweeping invalidation of any restrictions on abortion during the first trimester is impossible to justify under that standard, and the conscious weighing of competing factors that the Court’s opinion apparently substitutes for the established test is far more appropriate to a legislative judgment than to a judicial one. . . .

The fact that a majority of the States reflecting, after all the majority sentiment in those States, have had restrictions on abortions for at least a century is a strong indication, it seems to me, that the asserted right to an abortion is not ‘so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.’ Even today, when society’s views on abortion are changing, the very existence of the debate is evidence that the ‘right’ to an abortion is not so universally accepted as the appellant would have us believe.

To reach its result, the Court necessarily has had to find within the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment a right that was apparently completely unknown to the drafters of the Amendment. As early as 1821, the first state law dealing directly with abortion was enacted by the Connecticut Legislature. . . . By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, there were at least 36 laws enacted by state or territorial legislatures limiting abortion. While many States have amended or updated their laws, 21 of the laws on the books in 1868 remain in effect today. Indeed, the Texas statute struck down today was, as the majority notes, first enacted in 1857, and “has remained substantially unchanged to the present time.” . . .

There apparently was no question concerning the validity of this provision or of any of the other state statutes when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. The only conclusion possible from this history is that the drafters did not intend to have the Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the power to legislate with respect to this matter. . . .

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)

A person may choose to have an abortion until a fetus becomes viable, based on the right to privacy contained in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Viability means the ability to live outside the womb, which usually happens between 24 and 28 weeks after conception.

The law in Texas permitted abortion only in cases where the procedure was necessary to save the life of the mother. When Dallas resident Norma McCorvey found out that she was pregnant with her third child, she tried to falsely claim that she had been raped and then to obtain an illegal abortion. Both of these efforts failed, and she sought the assistance of Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington, who filed a claim using the alias Jane Roe for McCorvey. (The other named party, Henry Wade, was the District Attorney for Dallas County.) McCorvey gave birth to her child before the case was decided, but the district court ruled in her favor based on a concurrence in the 1965 Supreme Court decision of Griswold v. Connecticut, written by Justice Arthur Goldberg. This concurrence had found that there was a right to privacy based on the Ninth Amendment of the Constitution. However, the district court refrained from issuing an injunction to prevent the state from enforcing the law, leaving the matter unresolved.

- Linda Coffee (plaintiff)

- Sarah Weddington (plaintiff)

- Jay Floyd (defendant)

Issue: Whether a plaintiff still has standing to bring a case based on her pregnancy once she has given birth. Holding: Yes. The mootness doctrine does not bar her case from being heard, even though this individual plaintiff's position would no longer be affected, and she did not have an actual case or controversy. This situation fits within the exception to the mootness rule that covers wrongs that are capable of repetition yet evading review. Most cases are not heard through to appeal in a period shorter than a pregnancy, so strictly applying the mootness doctrine would prevent these issues from ever being resolved.

- Harry Andrew Blackmun (Author)

- Warren Earl Burger

- William Orville Douglas

- William Joseph Brennan, Jr.

- Potter Stewart

- Thurgood Marshall

- Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr.

The majority found that strict scrutiny was appropriate when reviewing restrictions on abortion, since it is part of the fundamental right of privacy. Blackmun was uninterested in identifying the exact part of the Constitution where the right of privacy can be found, although he noted that the Court had previously located it in the Fourteenth rather than the Ninth Amendment. The opinion applied a controversial trimester framework to guide judges and lawmakers in balancing the mother's health against the viability of the fetus in any given situation. In the first trimester, the woman has the exclusive right to pursue an abortion, not subject to any state intervention. In the second trimester, the state cannot intervene unless her health is at risk. If the fetus becomes viable, once the pregnancy has progressed into the third trimester, the state may restrict the right to an abortion but must always include an exception to any regulation that protects the health of the mother. The Court, which included no female Justices at the time, appears to have been confused about the differences between the trimester framework and viability, which are not necessarily interchangeable. It is interesting to note that Blackmun was particularly invested in this case and the opinion, since he had worked at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota during the 1950s and researched the history of abortions there. This may explain why he framed the opinion largely in terms of protecting the right of physicians to practice medicine without state interference (e.g., by counseling women on whether to pursue abortions) rather than the right of women to bodily autonomy.

- Byron Raymond White (Author)

- William Hubbs Rehnquist

White criticized the majority's arbitrary choice of a rigid framework without any constitutional or other legal foundation to support it. He believed that this aggressive use of judicial power exceeded the Court's appropriate role by taking away power that rested with state legislatures and essentially writing laws for them. White argued that the political process was the appropriate mechanism for seeking reform, rather than letting the Court decide whether and when the mother should be a higher priority than the fetus.

- William Hubbs Rehnquist (Author)

Rehnquist expanded on the historical elements of White's argument. He researched 19th-century laws on abortion and the status of the issue at the time of both the Founding and the Fourteenth Amendment. His originalist approach led him to conclude that state restrictions on abortion were considered valid at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment, so its drafters could not have contemplated creating rights that conflicted with it.

Concurrence

- William Orville Douglas (Author)

More concerned with doctrinal sources than Blackmun, Douglas pointed out more forcefully that the Fourteenth Amendment rather than the Ninth Amendment is the appropriate source of the right of privacy.

- Potter Stewart (Author)

Stewart argued that the right of privacy was specifically rooted in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- Warren Earl Burger (Author)

Burger felt that two physicians rather than one should be required to agree to a woman's request for an abortion.

The Court was praised in many circles for its progressive attitude toward evolving social trends, even though the decision was framed in paternalistic language and seemed more focused on protecting physicians than women. However, many commentators have viewed its decision as a prime example of judicial "activism," a term that refers to when the Court is seen to infringe on the authority of other branches of government.. A magnet for controversy to the current day, Roe has been challenged consistently and lacks support from many current members of the Court. The trimester framework proved less workable than the majority had hoped, and decisions such as Planned Parenthood v. Casey have eroded what initially seemed like a sweeping statement in favor of women's rights. Many states that oppose Roe have enacted laws that will go into effect in the event that it is overturned.

U.S. Supreme Court

Roe v. Wade

Argued December 13, 1971

Reargued October 11, 1972

Decided January 22, 1973

410 U.S. 113

A pregnant single woman (Roe) brought a class action challenging the constitutionality of the Texas criminal abortion laws, which proscribe procuring or attempting an abortion except on medical advice for the purpose of saving the mother's life. A licensed physician (Hallford), who had two state abortion prosecutions pending against him, was permitted to intervene. A childless married couple (the Does), the wife not being pregnant, separately attacked the laws, basing alleged injury on the future possibilities of contraceptive failure, pregnancy, unpreparedness for parenthood, and impairment of the wife's health. A three-judge District Court, which consolidated the actions, held that Roe and Hallford, and members of their classes, had standing to sue and presented justiciable controversies. Ruling that declaratory, though not injunctive, relief was warranted, the court declared the abortion statutes void as vague and overbroadly infringing those plaintiffs' Ninth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. The court ruled the Does' complaint not justiciable. Appellants directly appealed to this Court on the injunctive rulings, and appellee cross-appealed from the District Court's grant of declaratory relief to Roe and Hallford.

1. While 28 U.S.C. § 1253 authorizes no direct appeal to this Court from the grant or denial of declaratory relief alone, review is not foreclosed when the case is properly before the Court on appeal from specific denial of injunctive relief and the arguments as to both injunctive and declaratory relief are necessarily identical. P. 123.

2. Roe has standing to sue; the Does and Hallford do not. Pp. 123-129.

(a) Contrary to appellee's contention, the natural termination of Roe's pregnancy did not moot her suit. Litigation involving pregnancy, which is "capable of repetition, yet evading review," is an exception to the usual federal rule that an actual controversy

must exist at review stages, and not simply when the action is initiated. Pp. 124-125.

(b) The District Court correctly refused injunctive, but erred in granting declaratory, relief to Hallford, who alleged no federally protected right not assertable as a defense against the good faith state prosecutions pending against him. Samuels v. Mackell , 401 U. S. 66 . Pp. 125-127.

(c) The Does' complaint, based as it is on contingencies, any one or more of which may not occur, is too speculative to present an actual case or controversy. Pp. 127-129.

3. State criminal abortion laws, like those involved here, that except from criminality only a life-saving procedure on the mother's behalf without regard to the stage of her pregnancy and other interests involved violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects against state action the right to privacy, including a woman's qualified right to terminate her pregnancy. Though the State cannot override that right, it has legitimate interests in protecting both the pregnant woman's health and the potentiality of human life, each of which interests grows and reaches a "compelling" point at various stages of the woman's approach to term. Pp. 147-164.

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman's attending physician. Pp. 163, 164.

(b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health. Pp. 163, 164.

(c) For the stage subsequent to viability the State, in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life, may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother. Pp. 163-164; 164-165.

4. The State may define the term "physician" to mean only a physician currently licensed by the State, and may proscribe any abortion by a person who is not a physician as so defined. P. 165.

5. It is unnecessary to decide the injunctive relief issue, since the Texas authorities will doubtless fully recognize the Court's ruling

that the Texas criminal abortion statutes are unconstitutional. P. 166.

314 F. Supp. 1217 , affirmed in part and reversed in part.

BLACKMUN, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which BURGER, C.J., and DOUGLAS, BRENNAN, STEWART, MARSHALL, and POWELL, JJ., joined. BURGER, C.J., post, p. 410 U. S. 207 , DOUGLAS, J., post, p. 209, and STEWART, J., post, p. 167, filed concurring opinions. WHITE, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which REHNQUIST, J., joined, post, p. 221. REHNQUIST, J., filed a dissenting opinion, post, p. 171.

- Opinions & Dissents

- Oral Arguments

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox!

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Roe v. Wade

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 21, 2023 | Original: March 27, 2018

Roe v. Wade was a landmark legal decision issued on January 22, 1973, in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Texas statute banning abortion, effectively legalizing the procedure across the United States. The court held that a woman’s right to an abortion was implicit in the right to privacy protected by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution . Prior to Roe v. Wade , abortion had been illegal throughout much of the country since the late 19th century. Since the 1973 ruling, many states imposed restrictions on abortion rights. The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade on June 24, 2022, holding that there was no longer a federal constitutional right to an abortion.

Abortion Before Roe v. Wade

Until the late 19th century, abortion was legal in the United States before “quickening,” the point at which a woman could first feel movements of the fetus, typically around the fourth month of pregnancy.

Some of the early regulations related to abortion were enacted in the 1820s and 1830s and dealt with the sale of dangerous drugs that women used to induce abortions. Despite these regulations and the fact that the drugs sometimes proved fatal to women, they continued to be advertised and sold.

In the late 1850s, the newly established American Medical Association began calling for the criminalization of abortion, partly in an effort to eliminate doctors’ competitors such as midwives and homeopaths.

Additionally, some nativists, alarmed by the country’s growing population of immigrants, were anti-abortion because they feared declining birth rates among white, American-born, Protestant women.

In 1869, the Catholic Church banned abortion at any stage of pregnancy, while in 1873, Congress passed the Comstock law, which made it illegal to distribute contraceptives and abortion-inducing drugs through the U.S. mail. By the 1880s, abortion was outlawed across most of the country.

During the 1960s, during the women’s rights movement, court cases involving contraceptives laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade .

In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a law banning the distribution of birth control to married couples, ruling that the law violated their implied right to privacy under the U.S. Constitution . And in 1972, the Supreme Court struck down a law prohibiting the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried adults.

Meanwhile, in 1970, Hawaii became the first state to legalize abortion, although the law only applied to the state’s residents. That same year, New York legalized abortion, with no residency requirement. By the time of Roe v. Wade in 1973, abortion was also legally available in Alaska and Washington .

In 1969, Norma McCorvey, a Texas woman in her early 20s, sought to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. McCorvey, who had grown up in difficult, impoverished circumstances, previously had given birth twice and given up both children for adoption. At the time of McCorvey’s pregnancy in 1969 abortion was legal in Texas—but only for the purpose of saving a woman’s life.

While American women with the financial means could obtain abortions by traveling to other countries where the procedure was safe and legal, or pay a large fee to a U.S. doctor willing to secretly perform an abortion, those options were out of reach to McCorvey and many other women.

As a result, some women resorted to illegal, dangerous, “back-alley” abortions or self-induced abortions. In the 1950s and 1960s, the estimated number of illegal abortions in the United States ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

After trying unsuccessfully to get an illegal abortion, McCorvey was referred to Texas attorneys Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington, who were interested in challenging anti-abortion laws.

In court documents, McCorvey became known as “Jane Roe.”

In 1970, the attorneys filed a lawsuit on behalf of McCorvey and all the other women “who were or might become pregnant and want to consider all options,” against Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County, where McCorvey lived.

Earlier, in 1964, Wade was in the national spotlight when he prosecuted Jack Ruby , who killed Lee Harvey Oswald , the alleged assassin of President John F. Kennedy .

Supreme Court Ruling

In June 1970, a Texas district court ruled that the state’s abortion ban was illegal because it violated a constitutional right to privacy. Afterward, Wade declared he’d continue to prosecute doctors who performed abortions.

The case eventually was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile, McCovey gave birth and put the child up for adoption.

On Jan 22, 1973, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, struck down the Texas law banning abortion, effectively legalizing the procedure nationwide. In a majority opinion written by Justice Harry Blackmun , the court declared that a woman’s right to an abortion was implicit in the right to privacy protected by the 14th Amendment .

The court divided pregnancy into three trimesters, and declared that the choice to end a pregnancy in the first trimester was solely up to the woman. In the second trimester, the government could regulate abortion, although not ban it, in order to protect the mother’s health.

In the third trimester, the state could prohibit abortion to protect a fetus that could survive on its own outside the womb, except when a woman’s health was in danger.

5 Historic Supreme Court Rulings Based on the 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment's guarantee to "due process" provided a basis for these five Supreme Court rulings that have impacted Americans' lives.

Reproductive Rights in the US: Timeline

Since the early 1800s, U.S. federal and state governments have taken steps both securing and limiting access to contraception and abortion.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Landmark Opinions on Women’s Rights

The Supreme Court Justice was the second woman to hold the role—and battled gender discrimination since the 1970s.

Legacy of Roe v. Wade

Norma McCorvey maintained a low profile following the court’s decision, but in the 1980s she was active in the abortion rights movement.

However, in the mid-1990s, after becoming friends with the head of an anti-abortion group and converting to Catholicism, she turned into a vocal opponent of the procedure.

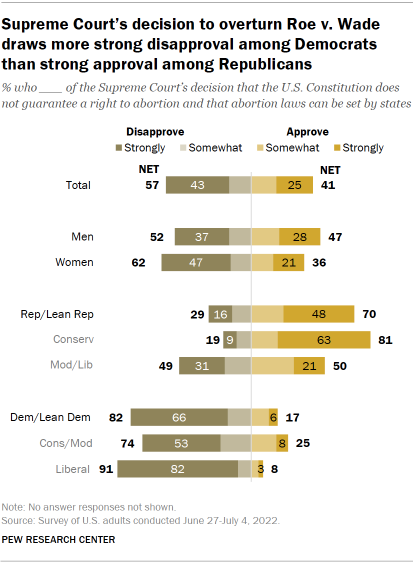

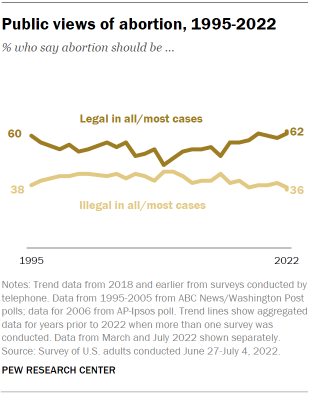

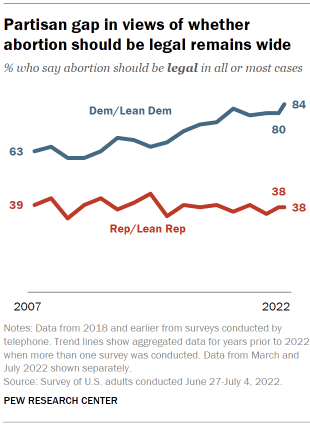

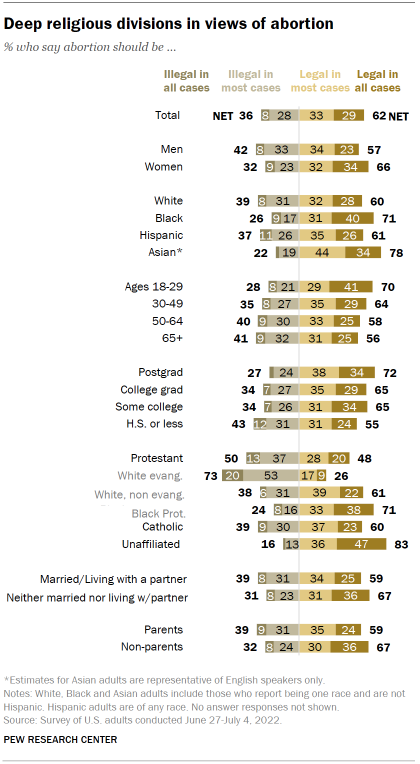

Since Roe v. Wade , many states imposed restrictions that weaken abortion rights, and Americans remain divided over support for a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

In 1992, litigation against Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act reached the Supreme Court in a case called Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey . The court upheld the central ruling in Roe v. Wade but allowed states to pass more abortion restrictions as long as they did not pose an “undue burden."

Roe v. Wade Overturned

In 2022, the nation's highest court deliberated on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization , which regarded the constitutionality of a Mississippi law banning most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Lower courts had ruled the law was unconstitutional under Roe v. Wade . Under Roe , states had been prohibited from banning abortions before around 23 weeks—when a fetus is considered able to survive outside a woman's womb.

In its decision , the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of Mississippi's law—and overturned Roe after its nearly 50 years as precedent.

Abortion in American History. The Atlantic . High Court Rules Abortion Legal in First 3 Months. The New York Times . Norma McCorvey. The Washington Post . Sarah Weddington. Time . When Abortion Was a Crime , Leslie J. Reagan. University of California Press .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Back to results

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

- Roe v. Wade

- Mary Ziegler Mary Ziegler College of Law, Florida State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.449

- Published online: 27 July 2017

Decided by the Supreme Court in 1973, Roe v. Wade legalized abortion across the United States. The 7-2 decision came at the end of a decades-long struggle to reform—and later repeal—abortion laws. Although all of the justices understood that Roe addressed a profoundly important question, none of them imagined that it would later become a flashpoint of American politics or shape those politics for decades to come.

Holding that the right to privacy covered a woman’s choice to terminate her pregnancy, Roe and its companion case, Doe v. Bolton , struck down many of the abortion regulations on the books. The lead-up to and aftermath of Roe tell a story not only of a single Supreme Court decision but also of the historical shifts that the decision shaped and reflected: the emergence of a movement for women’s liberation, the rise of grassroots conservatism, political party realignment, controversy about the welfare state, changes to the family structure, and the politicization of science. It is a messy and complicated story that evolved parallel to different ideas about the decision itself. In later decades, Roe arguably became the best-known opinion issued by the Supreme Court, a symbol of an ever-changing set of beliefs about family, health care, and the role of the judiciary in American democracy.

- pro-life movement

- pro-choice movement

Decided by the Supreme Court in 1973 , Roe v. Wade legalized abortion across the United States. Roe struck down a Texas law banning abortions unless a woman’s life was in danger, while a companion case, Doe v. Bolton , invalidated a Georgia statute that heavily regulated access. Even from a purely legal standpoint, Roe was a major case. In a single opinion, the justices expanded the ideas of constitutional privacy and equality, struck down over thirty state laws, and concluded that the fetus was not a person as defined by the Fourteenth Amendment. But as it lives on in the public imagination, Roe v. Wade refers not only to what the Court held in 1973 but also to the many meanings Americans later projected onto the decision in the decades to come.

Within months of the Court’s decision, scholars debated the merits of the method the Roe Court used to reach a decision. Over time, attacks on the decision multiplied. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a future justice of the Supreme Court, contended that the Court’s decision stopped the momentum of the abortion-rights cause by focusing “on a medically approved autonomy idea, to the exclusion of a constitutionally based sex equality perspective.” 1 In 1992 , Justice Antonin Scalia articulated the common view that Roe “destroyed the compromises of the past, rendered impossible the compromises of the future, [and] fanned into life an issue that has inflamed our national politics . . . ever since.” 2 Critics took issue with more than the reasoning of the Court’s decision. Like Scalia, law professors and historians concluded that Roe had eliminated consensus solutions on abortion and polarized gender politics more broadly.

But the political backlash to Roe was more gradual and complex than the firestorm described by Ginsburg and Scalia. Before the Supreme Court intervened, the social movements contesting the abortion issue already championed diametrically opposed constitutional rights. In the early 1970s, Republican leaders tried to make abortion a wedge issue, escalating a conflict that was already unfolding in states considering abortion-law reform. After Roe , the antiabortion movement became better organized, but the bitter stalemate described by some scholars and judges did not take hold until the later 1970s. Even when the abortion debate became extremely polarized, Roe alone was not to blame. Political party realignment, the emergence of the religious right, and the popularization of neoliberalism and small-government politics all raised the stakes of the debate.

Disentangling the myth and reality of Roe v. Wade offers an important window into the evolution of abortion politics and the broader changes to the nation in the closing decades of the 20th century . Better understanding Roe also illustrates how a judicial decision can become a canvas for beliefs, values, and historical events far removed from anything ever considered by the Court.

While Americans always terminated pregnancies, the political controversy now associated with it began relatively recently. During the 18th and 19th centuries , states did not criminalize the termination of pregnancy before “quickening,” the time when fetal movement could be detected. By the mid- 19th century , abortion had become a booming business, led by well-known practitioners like New York’s Madame Restell. The visibility of abortion, together with the murky distinctions among doctors, midwives, and other health providers, inspired a campaign to criminalize the procedure. Led by members of the American Medical Association, physician reformers worked to change ideas about when human life began and when abortion was moral. The physicians’ campaign came at a time when moral crusaders, Anthony Comstock among them, worked to introduce federal legislation to curb the spread of birth control and pornography. 3

By 1880 , every state had introduced criminal abortion laws, making narrow exceptions when the procedure was needed to save a woman’s life. Enforcement of the laws was uneven and difficult to predict. Physicians held varying ideas about when a medical condition justified abortion, and this uncertainty shaped enforcement of laws. Who faced punishment for criminal abortion was also complex. Although some state laws left open the possibility that women seeking abortion could face prosecution as an accomplice or conspirator, prosecutors generally targeted those who performed abortions, particularly when a woman died during a procedure. For some women forced to testify in court and cooperate with law enforcement, intense investigations, publicity, and exposure effectively replaced formal legal punishments. 4

By the 1930s and 1940s, improvements in obstetric and gynecological care disrupted the status quo. As fewer physicians could justify abortion as a means of saving a woman’s life, questions about the meaning of therapeutic exceptions took on new urgency. Hospitals created committees to limit the practice of therapeutic abortion. Family-planning organizations like the Planned Parenthood Federation of American hosted conferences on abortion, pushing for a new model law on the subject. In 1959 , the American Law Institute (ALI), a group of distinguished legal scholars and judges, released a draft proposal that would make abortion legal in cases of fetal abnormality, rape or incest, or a threat to the woman’s health. 5

In 1962 , when the ALI endorsed a final version of the recommendations as part of the Model Penal Code, Shirley Finkbine’s story made abortion front-page news. Finkbine learned that thalidomide, a drug she had taken while pregnant, could lead to severe birth defects. After failing to get an abortion in Arizona, she eventually traveled to Sweden to terminate her pregnancy. Her saga captured the public imagination, and in 1962 , a Gallup poll found that a majority of respondents believed that Finkbine had done the right thing. 6

In the early 1960s, an epidemic of German measles reinforced concerns about the threat of fetal abnormalities. Women exposed in the early months of pregnancy stood a high chance of bearing a child with fetal defects, and experts predicted that as many as 20,000 children would be born with serious disabilities as a result of the outbreak. Media coverage of “rubella babies” helped to change public understandings of abortion. For the first time, many believed that anyone could have a reason to seek out the procedure, including white, middle-class women. 7

Anxieties about German measles came at a time when attitudes about birth control were changing. After World War II, a baby boom convinced some policymakers that the world was on the brink of a population explosion. The population-control movement drew a diverse group of supporters. Cold War hawks worried that out-of-control growth would tip the balance in the conflict with the Soviet Union. Advocates of eugenic legal reform saw a reduction in the quantity of the population as the most politically realistic way to improve its quality. 8

Religious opposition to contraception had also begun to fade. Protestant denominations gradually revised their positions on contraception. Although the Catholic Church remained steadfast in its opposition, lay believers took a different view. Conventionally, believers saw opposition to birth control and abortion as interrelated. For this reason, growing public acceptance of contraception augured well for those seeking to legalize abortion.

While the climate for reform seemed promising, the formal push for it took shape slowly. In 1964 , Dr. Alan Guttmacher of Planned Parenthood organized the Association for the Study of Abortion as an educational organization. With only twenty members, the group primarily lent prestige to the unfolding in the states. In 1967 , Colorado became the first state to adopt a version of the ALI bill. By 1972 , thirteen states had followed.

Nevertheless, the reform laws pleased almost no one. The exceptions carved out by the ALI were vague and unpredictable. Afraid of civil lawsuits and jail time, doctors in reform states took an extremely cautious approach. Some responded by demanding the complete repeal of abortion restrictions, including doctors and population controllers. Whereas some physicians saw legal abortion as a matter of public health, population controllers argued that legalizing the procedure was necessary to conserve scarce national resources.

The repeal movement also struck a chord with the growing women’s movement. The National Organization for Women (NOW), a major feminist organization, demanded the repeal of abortion restrictions in 1968 . Feminists joined in calls for the right of a woman to control her own body and connected legalization to women’s ability to participate fully in the political, social, and economic life of the nation. Supporters of women’s rights also influenced the decision of other major organizations to endorse repeal, including Planned Parenthood in 1968 and NARAL (then the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws) in 1969 .

At the time repeal won support, conflict about abortion had already escalated. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Catholic Church wove concern about the termination of pregnancy into its campaign against birth control. By the 1950s, Catholic doctors and activists moved beyond religious arguments, insisting that legal abortion would violate the constitutional rights of the unborn child. As more states adopted a version of the ALI, abortion opponents changed course. Self-proclaimed right-to-lifers developed a single-issue approach and emphasized the right to life. Movement members saw these arguments as advantageous because some state courts had compensated parents for fetal injuries. Other pro-lifers took inspiration from Supreme Court decisions recognizing rights that were only implied in the text of the Constitution. A rights-based strategy had a broader appeal, helping the right-to-life movement win the support of some Protestants, Mormons, and Jews. 9

The outcome of political struggles over abortion remained unpredictable throughout the early 1970s. In addition to the states that adopted the ALI model, four others eliminated virtually all restrictions on the procedure. Right-to-lifers mobilized to reintroduce restrictions in New York following repeal in 1970 . The effort failed only because of a veto by Governor Nelson Rockefeller. In 1972 , right-to-lifers succeeded in blocking a Michigan referendum that would have liberalized abortion access. National party politics also contributed to a deepening divide on the issue. California Republicans had experimented with using abortion as a wedge issue since 1970 , and two years later, strategists working for Richard Nixon hoped to use the issue to convince Catholics to abandon the Democratic Party. 10

Before the Court heard any argument, abortion politics had become sharply polarized. It was hard to determine who had the upper hand in the battles unfolding from state to state, but with the Roe decision, the course of the conflict would change.

Constitutional Foundations

The groundwork for the constitutional strategy that played out in Roe began with a challenge to Connecticut’s ban on contraceptive use by married couples. In 1961 , a first attempt to undo the law failed. In Poe v. Ullman , the Court saw no need to address the constitutionality of the law when it was never enforced. A local Planned Parenthood affiliate staged a violation of the law, ensuring that it would return to the Supreme Court. 11

In 1965 , in a seven-to-two decision, the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut agreed that the Connecticut law violated a fundamental constitutional right to privacy. Griswold did not spell out precisely where in the Constitution the right to privacy could be found. Emphasizing the importance of marriage, William O. Douglas’s majority held that text of the Constitution implied the existence of other important liberties. 12

Supporters of legal abortion hoped that the courts would apply the privacy right more broadly. In 1969 , during his prosecution for performing an illegal abortion, Dr. Milan Vuitch argued that the Washington, DC, ordinance under which he was prosecuted was unconstitutionally vague. Vuitch claimed that the law was so poorly written that doctors would not know ahead of time if they had committed a crime. Although the justices in United States v. Vuitch rejected his argument, reformers were heartened by the Court’s 1972 in Eisenstadt v. Baird . 13

That case involved a Massachusetts law limiting single people’s access to birth control. Rather than relying on the privacy strategy honed by repeal proponents, the Court found that Massachusetts had violated the Equal Protection Clause. Eisenstadt reasoned that there was no rational basis for denying single people access to birth control when married people did not face the same issue. William Brennan’s majority sent a hopeful signal to champions of abortion reform. “If the right to privacy means anything,” Brennan reasoned, “it is the right of the individual . . . to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision to bear or beget a child.” 14

The Court already had Roe before it when Eisenstadt came down. Roe addressed a Texas law allowing abortion only when necessary to save a woman’s life, while Doe involved a Georgia version of the ALI reform bill. While the justices did not easily reach a consensus about the Georgia law, there seemed to be a majority convinced that the Texas law was unconstitutional. Harry Blackmun circulated a majority holding that the law was unconstitutionally vague, but he was unhappy with the lukewarm response from his colleagues and narrowly convinced his colleagues to hold the case for re-argument. 15

When the case returned to the Court, the briefs submitted by the parties and amicus curiae put on display a wide a range of constitutional arguments about abortion. Americans United for Life, an antiabortion group, highlighted the harms that women supposedly experienced as a result of abortion, while the Planned Parenthood Federation of America laid out evidence of the safety of the procedure and the injuries attributable to back-alley abortions. Friend-of-the-court briefs emphasized that abortion undercut women’s interests in liberty, equality, and dignity. Antiabortion briefs pointed to the personhood of the fetus and identified a fundamental right to life in the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court’s Decision

When the Court handed down Roe in January 1973 , the seven-to-two majority little resembled the draft Blackmun had circulated. Blackmun’s majority began with a history of attitudes toward abortion. Here, Roe emphasized that bans on abortion were recent—dating only to the 19th century . Blackmun also emphasized that major professional organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American Bar Association, had joined calls for legalization.

Roe next held that “[t]he right to privacy is . . . broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” The majority stressed the injuries a woman could experience as the result of an unplanned pregnancy, reiterating that the decision belonged to “the woman and her responsible physician.” 16

The Court weighed several potential interests against this constitutional right. First, Roe considered whether the fetus should be considered a person under the Fourteenth Amendment. If the Court answered the question in the affirmative, then the unborn child would be entitled to legal rights, making legal abortion problematic. Canvassing other uses of the word “person” in the constitutional text, the Court concluded that the term applied only after birth.

Next, the Court asked whether the state had a compelling interest in protecting life from the moment of conception. Reasoning that medical, religious, and philosophical authorities had been unable to reach a consensus about when life began, Roe held that Texas could not override the woman’s constitutional rights by adopting one theory over another.

Insisting that the government still had important interests in regulating abortion, the Court set out a trimester framework that would apply to any regulation of abortion. In the first trimester, the state had to leave the decision to the woman and her physician. During the second trimester, laws could regulate abortion to protect women’s health. Only after viability, the point at which a child could survive outside the womb without medical intervention, could the state promote an interest in fetal life.

Doe and Roe struck down the Georgia and Texas laws, functionally invalidating every abortion law then on the books. Doe upheld only a requirement that a physician had to base a decision on “his best clinical judgment,” reasoning that the term required a physician to consider a woman’s age and physical, emotional, and psychological condition. 17

Roe touched off intense discussion in the legal academy. It was no surprise that conservative law professors, many of whom had criticized earlier decisions by the Court under Earl Warren and Warren Burger, saw Roe as flawed. However, Roe also created a crisis for liberal academics. Some, like Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School, became the first of many to offer a sounder constitutional foundation for the abortion right. Others saw Roe as a signal of the problems with a particular approach to judging, one that discounted the will of the people. 18

Academic analysis of Roe ensured that the decision would become a prime example in scholarly discussions of the role of the judiciary in modern America. Should—and could—courts act as engines of social change? How could the courts act aggressively without interfering with the nation’s commitment to democracy? Roe soon became a key example of the problems with an “activist” judiciary.

Roe also helped to nationalize antiabortion activities. Led by the National Right to Life Committee, right-to-lifers prioritized a constitutional amendment that would restore the right to life, reverse Roe , and ban abortion across the country. For years, movement organizations endlessly debated what a perfect amendment would involve. While fighting about the details, activists agreed on the broad outlines of a constitutional vision. For the most part, right-to-lifers did not immediately take an interest in arguments about judicial activism. Instead of blaming the Court for inventing a constitutional approach whole cloth, movement members faulted the justices for ignoring the unborn child’s right to life and equal treatment.

The abortion-rights movement also changed in the aftermath of Roe . While concerns about women’s rights had always been central to some in the movement, leading organizations like NARAL and Planned Parenthood had sometimes avoided arguments about equality or autonomy for women, believing them to be unnecessarily controversial. After Roe , women took on positions of leadership in most major abortion-rights organizations and emphasized ideas about women’s rights that they tied to Roe itself. At the same time, scandals consuming the population-control movement made it less attractive to tout abortion as a means of curbing demographic growth. A wave of involuntary sterilizations made news not long after the leaders of developing countries charged population controllers with racism and coercion.

The medical practice of abortion also changed in the aftermath of legalization. Following the decision of Roe , a network of clinics opened to serve clients. In the late 1970s, the National Abortion Federation (NAF) organized to set medical standards, provide mutual support, and lend a political voice to abortion providers. After legalization, providers grew concerned that saline abortions, then-common procedures performed by injecting fluid into the uterus, were time consuming, painful, and emotionally difficult for patients. Doctors developed dilation and evacuation, a procedure involving the dilation of the cervix and removal of any uterine contents. Dilation and evacuation proved to be safer and less taxing for staff and patients. 19

Even so, the threat of criminal prosecution was never far away. In the mid-1970s, Boston prosecutors brought manslaughter charges against Dr. Kenneth Edelin for performing an abortion by hysterotomy, a second-trimester procedure similar to a cesarean section. Edelin’s conviction was ultimately overturned on appeal, but the threat of legal intervention scared abortion providers. Many committed to avoiding Edelin’s fate by using only techniques that would eliminate the risk of a live birth during abortion.

Meanwhile, Congress refused to take action on an antiabortion constitutional amendment. Right-to-lifers had more success in the courts. Founded as an educational organization, Americans United for Life (AUL) created an antiabortion public-interest law firm. Rather than asking for the recognition of the right to life, AUL planned to argue that some abortion restrictions were constitutional under Roe .

With the passage of the Hyde Amendment in 1976 , AUL and its allies believed that an incremental attack on Roe would pay off. Following a series of state and local laws, the Hyde Amendment, a rider to an appropriations bill, prohibited Medicaid reimbursement for most abortions. Although the precise scope of the amendment sparked a fight every year, it threatened to cut off abortion access for poor women who could not afford the procedure.

When the Court rejected a constitutional challenge to the Hyde Amendment, some movement members saw the potential for something much more. The movement embraced a form of incrementalism, sponsoring state legislation that might survive Supreme Court review and then litigating to defend it. In this way, the movement planned to hollow out the Court’s decision until it had no real meaning.

Right-to-lifers also influenced electoral politics. Antiabortion political action committees claimed to have influenced key congressional races in the late 1970s. As their opposition evolved, supporters of abortion rights committed to becoming more politically savvy. Arguments about a right to choose had circulated for years, but NARAL and other movement organizations saw the idea of choice as a way to convince ambivalent voters.

While compromise on the abortion issue seemed possible, some activists tried to find common ground on other gender issues, including pregnancy-discrimination legislation. By the early 1980s, however, an evolving political environment ensured that the abortion debate would only become only more bitter. Led by former insiders like Paul Weyrich, the New Right hoped to force the Republican Party to the Right. Weyrich and his allies believed that conservative evangelical Protestants and Catholics could swing elections their way. With Weyrich’s help, new groups organized conservative evangelicals, including the Moral Majority ( 1979 ). 20

Aligning more closely with the newfound Religious Right guaranteed financial stability and political influence for the antiabortion movement. Right-to-lifers also gravitated toward conservatism because of the changing party politics of abortion. Although Republicans had tried to make abortion an election issue in the early 1970s, both parties avoided taking a clear position for most of the decade. The parties took contrasting stands on the issue during the 1976 election, but by 1980 , the divide between Republicans and Democrats had become far more pronounced. Ronald Reagan, who had taken antiabortion positions since 1976 , ran on a Republican platform that endorsed a fetal protective amendment to the Constitution. Carter took the position that Roe was the law of the land and deserved respect. At the end of the election season, the Republican Party had started a relationship with the antiabortion movement that would shape activists’ cause in coming decades.

After Reagan’s election, hopes for a fetal-protective constitutional amendment ran high, but right-to-lifers could not agree on how to proceed. Movement incrementalists favored an approach that would overrule Roe , while hardliners opposed anything that would stop short of ending abortion. By 1983 , a last-ditch attempt to pass the Hatch-Eagleton Amendment failed, convincing abortion opponents that the way forward depended on the courts. Movement leaders worked to popularize claims about judicial activism that had already shaped academic discussion.

The Court’s most recent abortion decision, City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health ( 1983 ), only intensified right-to-lifers’ focus. Reagan’s first nominee, Sandra Day O’Connor, dissented from a decision striking down an ordinance that abortion opponents had promoted as a model across the country. Her vote convinced some right-to-lifers that changing the Court’s composition could pay dividends for those dedicated to overturning Roe . 21

In the next decade, the Supreme Court majority in favor of abortion rights shrunk. The Court upheld several parental-consultation laws, pleasing abortion opponents who believed that minors’ rights could be a weakness for the opposition. In Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ( 1986 ), the Court again struck down a multi-restriction law, but four justices dissented from the majority. Throughout the 1980s, because of decisions like Thornburgh , Supreme Court nominations became more of a focal point during presidential elections, and members of Congress routinely asked judicial nominees for their views about Roe . In 1987 , the most intense such hearing resulted in the defeat of Robert Bork’s nomination to the nation’s highest court. After Bork, judicial nominations remained intensely political. 22

In 1989 , the Court seemed ready to overrule Roe altogether. A plurality opinion, Webster v. Reproductive Health Services , upheld most of a challenged Missouri law. Three justices suggested that “the key elements of the Roe framework . . . are not found in the text of the Constitution, or any place else anyone would expect to find a constitutional principle.” While Justice O’Connor reasoned that the statute was compatible with Roe , Justice Antonin Scalia called for overruling Roe . Webster convinced many that Roe would be overturned soon, if it had not been already. 23

The post- Webster period saw both sides experiment with different strategies. Some right-to-lifers grew frustrated with the pace of change and tried to blockade clinics directly. Led by Randall Terry’s Operation Rescue, clinic blockaders took to the streets at a time when clinic violence was on the rise. Bombings, acid attacks, and vandalism led to a decrease in the number of doctors performing abortions. In the wake of the murder of doctors and clinic staff, Congress passed the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (FACE), a law making it a crime to use force, threats, or physical obstruction to prevent people from entering reproductive-health clinics. The clinic-blockade movement declined because of internal divisions, crushing civil penalties, and criminal convictions. 24

Even though clinic blockaders lost credibility, antiabortion violence tested the relationship between providers and those in the political wing of the abortion-rights movement. While political operatives could use the violence to energize supporters and raise money, providers felt vulnerable and unprotected. Supporters of abortion rights invested more in politics. The leaders of the pro-choice movement believed that a decision overruling Roe would energize supporters of legal abortion and put many more sympathetic politicians in office.

By 1990 , Roe had taken on many meanings. Right-to-lifers sometimes presented Roe as a sign of the decay of the traditional family and a culture of selfishness. Others still identified Roe with the rejection of a right to life that defined a cultural tradition of protecting the vulnerable. As part of its “Who Decides?” campaign, NARAL made Roe a symbol of privacy from an overreaching state. Feminists often described Roe as a decision involving women’s autonomy and right to equal treatment. Roe had become as fluid as it was widely known. 25

Casey and the Undue Burden Test

In 1992 , in the decision of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey , the Court defied most expectations. Casey involved a challenge to five provisions of Pennsylvania’s Abortion Control Act, but the case also asked the Court to explain more clearly what would become of Roe . The plurality began by confirming “the essential holding” of Roe that the Constitution protected a liberty interest that covered abortion. The plurality linked abortion to established case law on “personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing and education.” Casey described a similar autonomy interest at stake in abortion—the “right to define one’s own concept of existence.” 26

Casey suggested that the abortion right mattered because of women’s interest in equality as well as autonomy. Given the consequences of an unplanned pregnancy, the woman’s suffering was “too intimate and personal for the State to insist, without more, upon its vision of the woman’s role.” 27

Casey next considered whether there were reasons to depart from stare decisis , the respect due to prior precedents. The plurality concluded that time had not proven Roe to be unworkable or eroded its doctrinal underpinnings. The Court also emphasized the extent to which women had come to rely on the existence of legal abortion in ordering their lives.

Nevertheless, the plurality concluded that medical advances had made Roe ’s trimester framework obsolete. Casey first held that the government’s interest in fetal life continued throughout pregnancy rather than starting after viability. Describing the trimester divisions as rigid and unnecessary, the Court set them aside. Instead, courts would evaluate future abortion regulations under the undue-burden test. A restriction would be unconstitutional if it had “the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a non-viable fetus.” 28

The Court went on to uphold all but one of the Pennsylvania regulations. Supporters of abortion rights took some hope from Casey ’s holding on a spousal-consultation law. Recognizing that only a small number of women would refrain from telling their spouses because of fears of abuse, Casey nonetheless concluded that the restriction created an undue burden. The plurality also suggested that spousal-consultation laws rested on damaging stereotypes about gender roles.

Right-to-lifers saw the Court’s analysis of an informed-consent provision as especially significant. Casey reasoned that laws requiring providers to recite a script would be constitutional so long as the information included was “truthful and non-misleading.” Casey rejected the idea that such a regulation would compromise the rights of women or physicians’ interest in free speech. The Court also repeated an argument right-to-lifers had used since before Roe about the negative effect of abortion on women. “In attempting to ensure that a woman apprehend the full consequences of her decision,” the Court reasoned, “the State furthers the legitimate purpose of reducing the risk that a woman may elect an abortion, only to discover late, with devastating consequences, that her decision was not fully informed.” 29

After Casey

Casey redefined Roe and changed the course of the conflict. Right-to-life groups used new informed-consent measures as a vehicle for claims about the negative effects of abortion on women. Abortion opponents also redoubled their efforts to introduce onerous facilities regulations, some of which required clinics to meet the same standards as hospitals. Groups like NARAL vowed to make abortion “legal, safe, and rare,” promoting access to contraception as well as abortion. Following the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, other activists worked to spread the idea of reproductive justice, a framework that brought together access to abortion, contraception, and sex education with demands for the means and support women needed to raise children.

By the mid-1990s, those on opposing sides battled about a particular late-term abortion procedure, intact dilation and extraction. Information about the procedure became public after an abortion opponent leaked part of a presentation given by Dr. Martin Haskell at the annual convention of the National Abortion Federation. Douglas Johnson of the National Right to Life Committee described the procedure as “partial birth abortion,” and movement members launched a campaign to ban it. President Bill Clinton twice vetoed a federal ban on the procedure. In 2000 , in Stenberg v. Carhart , the Supreme Court struck down a similar state law, emphasizing that it made no exception when the procedure was needed to protect a woman’s health. Three years later, President George W. Bush signed the Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act into law. 30

In 2007 , the Supreme Court decided a constitutional challenge to the federal law. In a five-to-four decision, Gonzales v. Carhart applied Casey ’s undue-burden test and upheld the ban. Among the legitimate purposes identified, the Court was protecting women from post-abortion regret. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy saw it as “self-evident that a mother who comes to regret her choice to abort must struggle with grief more anguished . . . when she learns, only after the event, what she once did not know: that she allowed a doctor to pierce the skull and vacuum the fast-developing brain of her unborn child.” Carhart also rejected a challenge to the law based on its lack of a health exception. Citing scientific uncertainty about when intact dilation and extraction would be necessary to help a woman, the Court reasoned that legislation could survive a facial challenge. 31

Carhart exposed the extent to which abortion care had changed. While hospitals had performed most abortions in the immediate aftermath of Roe , almost all women sought out the procedure at independent clinics. Planned Parenthood had stayed mostly out of the abortion business when NAF was founded. By the mid-1980s, the national Planned Parenthood office took a more prominent role in political advocacy for abortion rights. Over time, the number of affiliates offering abortion services increased: whereas the 1979 NAF directory listed only one Planned Parenthood clinic, roughly half the affiliates did so by 2015 . Although many affiliates provided a wide range of reproductive services, Planned Parenthood became the nation’s most visible abortion provider.

Almost a decade went by before the Supreme Court would hear another abortion case. In Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt , the Court heard a challenge to two provisions of Texas’s HB2, a law alleged to protect women from unsafe clinics and providers. One required doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges within thirty miles. A second mandated that abortion clinics comply with the many regulations governing ambulatory surgical centers.

By a five-to-three vote, the Court struck down both regulations. The majority agreed with a trial court that HB2 would dramatically undermine access to abortion in the state. Nor was the majority convinced that the law protected women’s health. More importantly, the Court reinterpreted the undue-burden test. Whole Woman’s Health instructed courts to balance the burdens of a law against its benefits. Moreover, the Court clarified that courts should collect extensive evidence about the impact of a law rather than deferring to legislators’ analyses of it.

The abortion debate seemed likely to change again in the wake of Whole Woman’s Health . Some pro-lifers turned back to fetal-protective laws, emphasizing statutes that would ban abortion after twenty weeks, the time when activists claimed that the unborn child could experience pain. Others outlawed “dismemberment” abortions, measures that seemed likely to reach dilation and evacuation, the most common second-trimester procedure. Some movement members argued that it was too early to give up on strategies emphasizing the supposed negative effect of abortion on women.

Supporters of legal abortion also faced an uncertain future. Following the presidential 2016 election, Donald J. Trump vowed to nominate pro-life judges. With control of both houses of Congress, Republicans planned to defund Planned Parenthood and hoped to ban abortion after twenty weeks. With the membership of the Supreme Court likely to change, the fate of Roe seemed up in the air.

In the decades after its decision, Roe has continued to cast a long shadow over American law and culture. Roe receives credit (or blame) for eliminating possible compromises on a range of gender issues. Feminists identify it with what they see as a damaging brand of single-issue politics that leave out poor and non-white women. Nevertheless, Roe itself emerged from some of the major upheavals of the 20th century —medical advancements, changes to the family structure, battles about family planning, eugenics, and individualism.